Abstract

Background

The therapeutic efficacy of coenzyme Q10 on patients with cardiac failure remains controversial. We pooled previous clinical studies to re-evaluate the efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in patients with cardiac failure.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Clinical Trials.gov databases for controlled trials. The endpoints were death, left heart ejection fraction, exercise capacity, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) cardiac function classification after treatment. The pooled risk ratios (RRs) and standardized mean difference (SMD) were used to assess the efficacy of coenzyme Q10.

Results

A total of 14 RCTs with 2149 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Coenzyme Q10 decreased the mortality compared with placebo (RR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.50–0.95; P = 0.02; I 2 = 0%). A greater improvement in exercise capacity was established in patients who used coenzyme Q10 than in those who used placebo (SMD = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.02–0.30; P = 0.04; I 2 = 54%). No significant difference was observed in the endpoints of left heart ejection fraction between patients who received coenzyme Q10 and the patients in whom placebo was administered (SMD = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.02–1.12; P = 0.04; I 2 = 75%). The two types of treatment resulted in obtaining similar NYHA classification results (SMD = −0.70; 95% CI = −1.92–0.51; P = 0.26; I 2 = 89%).

Conclusion

Patients with heart failure who used coenzyme Q10 had lower mortality and a higher exercise capacity improvement than the placebo-treated patients with heart failure. No significant differences between the efficacy of the administration of coenzyme Q10 and placebo in the endpoints of left heart ejection fraction and NYHA classification were observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome that results in an inadequate cardiac output and reduced ejection capacity due to serious structural or functional abnormalities of the heart. Millions of people are diagnosed with heart failure worldwide every year [1], which is the most frequent cause of hospitalization and disability [2, 3]. Although there have been major improvements in the pharmacological management of heart failure, death rates continue to exceed 10% per year, reaching between 20% to 50% in severe cases [4]. Supplementary oral administration of coenzyme Q10 has been found to increase coenzyme Q10 levels in plasma, platelets, and white blood cells [5]. Studies also evidenced that the concentration of coenzyme Q10 in the plasma of patients with heart failure is an independent predictor of heart failure death [6]. However, most of the reported clinical trials have been performed on a limited sample size. For example, Mortensen [7] reported that coenzyme Q10 decreased the mortality and improved the left heart ejection fraction compared with the placebo used, whereas no significant difference between the endpoints of mortality and left heart ejection fraction were found by Khatta [8]. We pooled previous studies to evaluate the efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in heart failure treatment to provide a data-driven concept for clinical practice.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Clinical Trials.gov databases from database inception until December 25 2016, using the keywords “coenzyme Q10”, “ubiquinone Q10”, “cardiac failure”, and “heart failure”. A sensitive filter for randomized controlled trials was utilized for the search. In addition, references from randomized trials and relevant reviews were hand-searched for additional trials that were not identified in the database search.

Study selection

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) patients with heart failure; (2) randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy of coenzyme Q10 versus placebo and other drugs; (3) clinical outcomes were reported, such as death, left heart ejection fraction, exercise capacity, NYHA classification, and adverse events; Reviews, meta-analyses, and observational studies were excluded. The meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [9].

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators independently extracted data from the relevant sources. Authors were contacted when data were incomplete or unclear, and conflicts were resolved by discussion. For the cross-over studies, single-phase data were extracted. Baseline demographic characteristics of the patients (sample size, diabetes percent, age, sex, and intervention in the experimental and control group) were collected from the eligible studies. The occurrence rates of the following events were abstracted: death. Mean and standard values of the following events were abstracted: left heart ejection fraction, exercise capacity, and NYHA classification. According to the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.0.2, last update September, 2009); the quality of the information accessed in each of the studies was classified as low, unclear, or high by evaluating the following seven components: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other issues.

Data analysis

Binary classification variables of the clinical endpoints were measured by using the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The continuous variables of the clinical endpoints were determined by using the standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs. Two-sided P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. A random-effects model was used to calculate all pooled estimates. Small-study and publication biases were assessed by funnel plot analysis and Egger’s test. Data analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.2 software (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2013), and sensitivity analysis was performed by Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Data search results

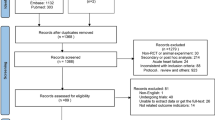

We identified 14 trials [7, 8, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] out of 1472 records, that satisfied our inclusion criteria, as can be seen in the selection procedure depicted in Fig. 1. A total of 1064 patients were randomized to a coenzyme Q10 (treatment) group, and 1085 patients were randomized to a placebo (control) group. The baseline demographic characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 1. The quality assessment data are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. S1 and Fig. S2. All clinical trials included in our study were characterized by a low risk of blinding of participants and outcome assessment, and selective outcome reporting. In addition, only one study with complete details of allocation concealment and three studies with unclear risk of incomplete outcome data which we included. In conclusion, the trials included in the present analysis were middle- or high-quality studies.

Results of mortality

The analysis of mortality showed that 55 out of 904 patients from the coenzyme Q10 group and 83 out of 923 from the control group died. The mortality was decreased by coenzyme Q10 compared with placebo (RR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.50–0.95; P = 0.02; I 2 = 0%) as shown in Fig. 2.

Results of left heart ejection fraction

In our study, nine clinical trials reported the endpoint of left heart ejection fraction, in which 460 patients were assigned to coenzyme Q10 treatment arm and 481 patients were assigned to placebo treatment arm. Patients who used coenzyme Q10 and placebo associated with similar left heart ejection fraction (SMD = 0.14; 95% CI = −0.08–0.37; P = 0.22; I 2 = 54%) when the random-effects was used as shown in Fig. 3.

Results of the exercise capacity test

In our study, four clinical trials reported the endpoint of exercise capacity in which 132 patients received treatment with coenzyme Q10, and 132 patients were treated with placebo. Using the random-effects model, we found that the exercise capacity was more significantly improved in the patients who used coenzyme Q10 (measured as exercise duration or walking distance, or both) than in the patients who used placebo (SMD = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.02–1.12; P = 0.04; I 2 = 75%) (Fig. 4).

Results of NYHA classification

Three clinical trials reported the endpoints of NYHA classification, in which 66 participants were given therapy with coenzyme Q10, and 60 participants were administered therapy with placebo. The random-effects model used exhibited no significant differences between these two types of treatment (SMD = −0.70; 95% CI = −1.92–0.51; P = 0.26; I 2 = 89%) when (Fig. 5).

Publication bias analysis

Egger’s test results showed no significant evidence of publication bias in either endpoint (Table 2). All the Egger’s regression outcomes of these four clinical endpoints had a P-value >0.05, which demonstrated that no publication bias was present in our study. As illustrated in Fig. 6, similar results were obtained after excluding each individual study.

Discussion

Coenzyme Q10 is a ubiquitous fat-soluble compound involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Evidence suggests that this substance with antioxidant properties improves human immunity and overall vitality. Coenzyme Q10 plays an important role in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and the production of adenosine triphosphate [22]. A slight change in the levels of coenzyme Q10 may lead to significant alterations in respiratory rate [23]. In addition, by impediment of the reaction of NO with peroxide, coenzyme Q10 can reduce the overall peripheral resistance and improve the heart ejection function; thus, NO in the endothelial cells increases vascular smooth muscle relaxation, which prevents the occurrence of myocardial ischemia [24,25,26]. A balance between oxidative and antioxidant activities exists in the patients with heart failure, and the protective function of the antioxidant enzymes in the body is weakened. Oxygen free radicals cause cell damage by activating apoptosis and mitochondrial protein destruction by lipid peroxidation. The lack of coenzyme Q10 in human may increase the rates of heart failure by augmenting the pressure on the heart wall; this leads to an increase in energy expenditure, resulting in an imbalance between energy supply and demand [24]. In a previous study, coenzyme Q10 was founded can exert direct antioxidant effects through enhancing myocardium energy generation by promoting oxidative phosphorylation of the cells. Heart failure patients always have low concentration of coenzyme Q10 and the decrease of coenzyme Q10 with increasing severity of heart failure [10].

In previous studies, coenzyme Q10 reduced the mortality in patients with heart failure, improving heart ejection fraction [27, 28]. Meanwhile, coenzyme Q10 did not significantly improve the NYHA cardiac function in patients with heart failure, which is consistent with the results of a previous examination [29]. In this study, we found that coenzyme Q10 can improve exercise tolerance in patients with heart failure; however, in the investigation conducted by Madmani [30], this improvement was not statistically significant.

Our research is the newest meta-analysis that analyzes the efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in heart failure patients. Compared with the meta-analysis published by Madmani in 2014 [30], we included 14 additional clinical investigations and 2149 more participants than in the previously mentioned meta-analysis. Meanwhile, compare with the meta-analysis conducted by Fotino [29], we analysis the efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in the endpoints of mortality and NYHA classification. Because of the inclusion of different studies, varying results were obtained for the endpoint of exercise capacity. Patients who used coenzyme Q10 extended their exercise capacity to a more considerable extent than patients who received placebo.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations in our meta-analysis. First, the dose of coenzyme Q10 and the duration of treatment were not uniform which might have affected the reliability of our results. Second, several of the trials included were without detailed descriptions of allocation concealment and blinding, which might have led to bias. Third, insufficient clinical information was included on the endpoints of exercise capacity and NYHA classification, which might have caused heterogeneity which we were unable to estimate. In addition, the generally different design and characteristics of each trial might have also caused heterogeneity. Therefore, conducting more rigorous, large-sample, international trials is needed to confirm our results.

Conclusion

In patients with heart failure, the administration of coenzyme Q10 resulted in lower mortality and improved exercise capacity compared with the effects of placebo treatment. No significant difference was found between coenzyme Q10 and placebo in the endpoints of left heart ejection fraction and NYHA classification.

Abbreviations

- CIs:

-

confidence intervals

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- RRs:

-

pooled risk ratios

- SMD:

-

standardized mean difference

References

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, PE MB, JJ MM, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147–239.

Deedwania PC, Carbajal EV. Chapter 18. Congestive heart failure.In: Crawford MH, ed. CURRENT diagnosis & treatment: cardiology.3rd edn. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2009.

Massie BM, Shah NB. Evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors of heart failure: rationale for preventive strategies and comprehensive disease management[J]. Am Heart J. 1997;133(6):703–12.

Mahmood SS, Wang TJ. The epidemiology of congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study perspective[J]. Global heart. 2013;8(1):77–82.

Niklowitz P, Sonnenschein A, Janetzky B, Andler W, Menke T. Enrichment of coenzyme Q10 in plasma and blood cells: defense against oxidative damage[J]. Int J Biol Sci. 2007;3(4):257–62.

Molyneux SL, Florkowski CM, George PM, Pilbrow AP, Frampton CM, Lever M, Richards AM. Coenzyme Q10: an independent predictor of mortality in chronic heart failure[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(18):1435–41.

Mortensen SA, Rosenfeldt F, Kumar A, Dolliner P, Filipiak KJ, Pella D, Alehagen U, Steurer G, Littarru GP. The effect of coenzyme Q10 on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from Q-SYMBIO: a randomized double-blind trial[J]. JACC Heart failure. 2014;2(6):641–9.

Khatta M, Alexander BS, Krichten CM, Fisher ML, Freudenberger R, Robinson SW, Gottlieb SS. The effect of coenzyme Q10 in patients with congestive heart failure[J]. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(8):636–40.

Walther S, Schuetz GM, Hamm B, Dewey M. [Quality of reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses)][J]. RoFo : Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Rontgenstrahlen und der Nuklearmedizin. 2011;183(12):1106–10.

Alehagen U, Aaseth J, Johansson P. Reduced Cardiovascular Mortality 10 Years after Supplementation with Selenium and Coenzyme Q10 for Four Years: Follow-Up Results of a Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial in Elderly Citizens[J]. PloS one. 2015;10(12):e0141641.

Belardinelli R, Mucaj A, Lacalaprice F, Solenghi M, Seddaiu G, Principi F, Tiano L, Littarru GP. Coenzyme Q10 and exercise training in chronic heart failure[J]. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2675–81.

Hofman-Bang C, Rehnqvist N, Swedberg K, Wiklund I, Astrom H. Coenzyme Q10 as an adjunctive in the treatment of chronic congestive heart failure. The Q10 Study Group[J]. J Cardiac Fail. 1995;1(2):101–7.

Keogh A, Fenton S, Leslie C, Aboyoun C, Macdonald P, Zhao YC, Bailey M, Rosenfeldt F. Randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of coenzyme Q, therapy in class II and III systolic heart failure[J]. Heart, Lung Circ. 2003;12(3):135–41.

Morisco C, Trimarco B, Condorelli M. Effect of coenzyme Q10 therapy in patients with congestive heart failure: a long-term multicenter randomized study[J]. Clin Investig. 1993;71(8 Suppl):S134–6.

Morisco C, Nappi A, Argenziano L, Sarno D, Fonatana D, Imbriaco M, Nicolai E, Romano M, Rosiello G, Cuocolo A. Noninvasive evaluation of cardiac hemodynamics during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: effects of short-term coenzyme Q10 treatment[J]. Mol Aspects Med, 1994, 15 Suppl: s155-s163.

Munkholm H, Hansen HH, Rasmussen K. Coenzyme Q10 treatment in serious heart failure[J]. BioFactors (Oxford, England). 1999;9(2-4):285–9.

Pourmoghaddas M, Rabbani M, Shahabi J, Garakyaraghi M, Khanjani R, Hedayat P. Combination of atorvastatin/coenzyme Q10 as adjunctive treatment in congestive heart failure: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial[J]. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014;10(1):1–5.

Watson PS, Scalia GM, Galbraith A, Burstow DJ, Bett N, Aroney CN. Lack of effect of coenzyme Q on left ventricular function in patients with congestive heart failure[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(6):1549–52.

Zhao Q, Kebbati AH, Zhang Y, Tang Y, Okello E, Huang C. Effect of coenzyme Q10 on the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure[J]. J Invest Med Official Public Am Fed Clin Res. 2015;63(5):735–9.

Kocharian A, Shabanian R, Rafiei-Khorgami M, Kiani A, Heidari-Bateni G. Coenzyme Q10 improves diastolic function in children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy[J]. Cardiology in the young. 2009;19(5):501–6.

Permanetter B, Rossy W, Klein G, Weingartner F, Seidl KF, Blomer H. Ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10) in the long-term treatment of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy[J]. Eur Heart J. 1992;13(11):1528–33.

Crane FL. Biochemical functions of coenzyme Q10[J]. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(6):591–8.

Ueno H, Miyoshi H, Ebisui K, Iwamura H. Comparison of the inhibitory action of natural rotenone and its stereoisomers with various NADH-ubiquinone reductases[J]. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225(1):411–7.

van den Heuvel AF, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Wall EE, Blanksma PK, Siebelink HM, Vaalburg WM, van Gilst WH, Crijns HJ. Regional myocardial blood flow reserve impairment and metabolic changes suggesting myocardial ischemia in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(1):19–28.

Rosenfeldt F, Marasco S, Lyon W, Wowk M, Sheeran F, Bailey M, Esmore D, Davis B, Pick A, Rabinov M, Smith J, Nagley P, Pepe S. Coenzyme Q10 therapy before cardiac surgery improves mitochondrial function and in vitro contractility of myocardial tissue[J]. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(1):25–32.

Rosenfeldt F, Hilton D, Pepe S, Krum H. Systematic review of effect of coenzyme Q10 in physical exercise, hypertension and heart failure[J]. BioFactors (Oxford, England). 2003;18(1-4):91–100.

Soja AM, Mortensen SA.Treatment of congestive heart failure with coenzyme Q10 illuminated by meta-analyses of clinical trials[J]. Mol Aspects Med, 1997,18 Suppl:S159-S168.

Sander S, Coleman CI, Patel AA, Kluger J, White CM. The impact of coenzyme Q10 on systolic function in patients with chronic heart failure[J]. J Cardiac Fail. 2006;12(6):464–72.

Fotino AD, Thompson-Paul AM, Bazzano LA. Effect of coenzyme Q10supplementation on heart failure: a meta-analysis[J]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):268–75.

Madmani ME, Yusuf Solaiman A, Tamr Agha K, Madmani Y, Shahrour Y, Essali A, Kadro W. Coenzyme Q10 for heart failure[J]. The. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008684.

Acknowledgements

None declared.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL designed the study and wrote the manuscript. LL and YL performed the database search and data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As this is a meta-analysis, ethics approval and consent to participate were not required.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Risk of bias graph. Review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Figure. S2. Risk of bias summary. Review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. (DOCX 613 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, L., Liu, Y. Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in patients with cardiac failure: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17, 196 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0628-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0628-9