Abstract

Background

Several meta-analyses have indicated that periodontal disease (PD) are related to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). However, the association between PD and myocardial infarction (MI) remains controversial. Here we aimed to assess the association between PD and MI by meta-analysis of observational studies.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library were searched through July, 2016. Observational studies including cohort, cross-sectional and case–control studies reporting odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were included in the analysis. Either fixed or random-effects model were applied to evaluate the pooled risk estimates. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were also carried out to identify the sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by the Begg’s, Egger’s test and funnel plot.

Results

We included 22 observational studies with 4 cohort, 6 cross-sectional and 12 case–control studies, including 129,630 participants. Patients with PD have increased risk of MI (OR 2.02; 95% CI 1.59-2.57). Substantial heterogeneity in risk estimates was revealed. Subgroup analyses showed that the higher risk of MI in PD patients exists in both cross-sectional studies (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.07-2.73) and case–control studies (OR 2.93; 95% CI 1.95-4.39), and marginally in cohort studies (OR 1.18; 95% CI 0.98-1.42). Further, subgroup meta-analyses by location, PD exposure, participant number, and study quality showed that PD was significantly associated with elevated risk of MI.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis suggested that PD is associated with increased risk of future MI. However, the causative relation between PD and MI remains not established based on the pooled estimates from observational studies and more studies are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Periodontal disease (PD) is defined as chronic inflammation of the supporting structure of the teeth. PD is estimated to be detectable in 20-50% of the general population and a major cause of tooth loss in adults [1]. The symptoms include bleeding gums (gingivitis), the formation of gingival pockets and bone loss (periodontitis) and finally tooth mobility caused by biofilm and calculus [2]. PD is related to many risk factors, such as inflammation, gender, smoking, genetics and life styles, which were also implicated in cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [3].

A great body of evidence has investigated the association between PD and CVD. Even though a number of meta-analyses indicated the association between PD and CVD, the cause-and-effect relationship between them was still not established with current available evidence according to an American Heart Association scientific statement [4]. Meanwhile, no specified meta-analysis by now has been reported to investigate whether PD was associated with myocardial infarction (MI).

In 1989, Mattila et al. first reported oral health including PD was related to acute MI [5]. Since then, a variety of literatures explored the nature of the association between PD and MI. Several case–control, cross-section or cohort studies have indicated a significant association between PD and MI [6–17]. However, whether the association is causal is still a matter of debate. Some other studies found no such relationship [18–24]. Given the high prevalence of PD and MI, it is of great value to determine their association.

The purpose of this study was to examine the association between PD and MI in observational studies. By pooling data from individual studies and using meta-analysis, the statistical estimates of the association between PD and incidence of MI were obtained.

Methods

The meta-analysis was performed following the guidelines from Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group [25] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [26].

Eligibility criteria

Studies included for the meta-analysis if they referred to observational studies including cross-sectional, case–control, cohort and nested case–control studies. The article should estimate the association between PD and MI and provide the odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Search strategy

Pubmed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library Databases were searched to identify relevant studies through July 2016. The medical subject headings (MeSH terms) as well as free text terms were used in the search strategy. The terms applied were as follows: ("periodontal disease" OR "periodontitis" OR "periodontal" OR "periodontal attachment loss" OR "periodontal pocket" OR "alveolar bone loss") AND ("myocardial infarction" OR "acute myocardial infarction" OR "acute coronary syndrome" OR "cardiovascular disease" OR "coronary heart disease" OR "unstable angina") (Additional file 1: Table S1). The search was restricted to studies conducted on human subjects and published in English and Chinese. The bibliographies of the articles found were hand searched for possible additional studies.

Two reviewers (S. Xu and X. Liu) screened the titles and abstracts of the search results and articles were excluded if they did not meet the above-mentioned inclusion criteria.

Quality assessment

Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess the quality of the observational studies, including case–control and cohort studies [27] and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for cross-sectional studies [28]. For case–control and cohort studies, the quality was ranked as followed: low quality = 0-4; moderate quality = 5-7; high quality = 8-9.

To rank the cross-sectional studies, the AHRQ was quantified in the following way. An item would be scored ‘0’, if it was answered ‘NO’ or ‘UNCLEAR’. If it was ‘YES’, then this item was scored ‘1’. Article quality was ranked as follows: low quality = 0-3; moderate quality = 4-7; high quality = 8-11 [29].

Data extraction

Two reviewers (S. Xu and X. Liu) extracted the data from all included studies independently. Any discrepancies or uncertainties between the reviewers were resolved by consensus after rechecking the source and discussion with the third reviewer (Z. Qin). A data collection form was used to compile extracted study information and included the following items: first author’s surname, publication year, country of origin, sample size, population, study design, enrolled period, age ranges, PD exposure parameter, adjusted OR/RR and their 95% CI, P values and adjusting factors.

PD was defined to include self-report diagnosis, or any measure of disease according to clinical, radiographic and microbiological assessment (including pocket probing depth, attachment loss, bleeding on probing, plaque index, gingival index, X-ray and microbiological results). At the very beginning, all related OR/RR based on different PD assessments were extracted. The one selected for final meta-analysis was according to the frequency of each OR/RR in all included studies. The order in this study was clinical attachment loss (CAL), pockets deep and periodontal bone loss.

Data analysis

The OR was used in these studies, while RR and hazard ratio (HR) were considered equivalent. For one study that reported stratified OR/RR in different population, we considered each subgroup analysis as an independent study. Before pooling the data, ORs were transformed into their natural logarithm to stabilize their variance, normalize the distribution and then statistically pooled [30].

The heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by Cochrane Q test and quantified as I2 metric. For the Q statistic, a P-value <0.1 was considered statistically significant heterogeneity. For I2 statistic, a value of zero was considered no heterogeneity, 25%-49% low, 50%-74% moderate, and above 75% high, respectively. To explore possible reasons for heterogeneity and test the robustness of the association, subgroup analyses were performed based on study design, methodological quality, gender, locations and PD exposure assessment parameters. When obvious heterogeneity across studies exists, the random-effect model was used to calculate the pooled estimates. Otherwise, the fixed-effect model was applied.

Publication bias was assessed by both Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s linear regression test. Funnel plots were also generated to assess the publication bias.

STATA statistical software, version 11.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for analysis. P values were 2-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significantly otherwise indicated.

Results

Literature search

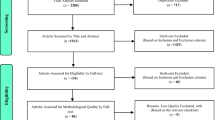

Initially, a total of 2558 articles were identified from PubMed (2041 articles), EMBASE (415 articles) and the Cochrane Library Database (102 articles) search. Of these citations, after evaluating the titles and abstracts, 373 studies were chosen for further review by reading the full text. Among them, 353 literatures were excluded because 286 articles were irrelevant, 14 had no OR/RR values, 28 had no clearly MI endpoint, 3 were not treated PD as exposure and 22 had no original data. Finally 22 studies from 20 articles representing 129,630 participants were included in our meta-analysis [6–24, 31]. See Fig. 1 for the flow chart of the study selection process.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of each study were demonstrated in Table 1, with adjusted covariates of each study presented. Four prospective cohort studies, 6 cross-sectional and 12 case–control studies evaluated the association between PD and MI. Case–control studies included a total of 2912 cases of MI and 3291 controls [6–15, 24]. All studies were published from 1996 to 2016. The reported age ranged from 23 to 83 years. The enrolled years of patients varied from 1982 to 2014. Among 22 studies, 8 were carried out primarily in America [8, 9, 16, 18, 21–23], 5 studies were conducted in Asian countries [12, 13, 20, 31] and 9 studies were from European countries [6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17, 19, 24]. Sixteen articles reported the OR values between PD and MI, 2 articles gave the HR and 2 articles presented with RR values. In 2 of the studies, OR/RR was less than one [20, 24]. Only two studies did not perform the adjustments for potential confounders [10, 19]. Fourteen studies showed PD was associated with MI [6–17, 31], while 8 studies demonstrated PD was not related to MI [18–24, 31]. PD exposure parameters varied among studies including clinical attachment loss (CAL), probing depth, deep pockets, and periodontal bone loss. The quality of the studies was high overall, without remarkable limitations identified (Additional file 2: Table S2; Additional file 3: Table S3).

Meta-analysis

The OR/RR from 22 studies were pooled and analyzed as presented in Fig. 2. Overall, the PD had statistically significant correlation with MI risk (OR = 2.02, 95% CI 1.59-2.57). A severe statistical heterogeneity among studies was revealed (Q = 152.77, P < 0.001, I2 = 86.3%). Sensitivity analysis showed two studies contributed most to the heterogeneity [6, 10]. Although the sensitivity remains marked, the Q value and I2 decreased to 70.68, and 73.1%, respectively. In the subgroup analysis by type of study (Fig. 3), cohort studies showed marginally increased risk of MI (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.98-1.42; I2 = 64.8%, n = 4) [16, 21–23], while PD increased the risk of MI in both cross-sectional studies (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.07-2.73; I2 = 16.7%, n = 6) [17–20, 31] and case–control studies (OR 2.93, 95% CI 1.95-4.39; I2 = 90.2%, n = 12) [6–15, 24].

By removing each study at a time, sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the influence of each study on the pooled OR. By omitting one study in turn, the pooled OR and 95% CI was not modified significantly (Fig. 4). This sensitivity analysis indicated that the results of this meta-analysis were stable and reliable.

Additionally, publication bias was observed from Egger’s Test (P = 0.013), Begg’s Test (P = 0.195), and Funnel plot (Fig. 5). Trim and fill algorithm analysis was performed and the analysis showed “no trimming performed; data unchanged”.

Subgroup analysis

To examine the stability of the studies, subgroup analyses were carried out based on several factors. Patients with PD had increased risk of MI across most subgroups by location, PD exposure parameters and study quality (Table 2). In the gender-specific subgroup, 3 female pooled studies showed an increased risk of MI (OR = 1.64, 95% CI 1.20-2.25) [8, 18, 23], while the pooled results in the 4 male studies were marginally increased (OR = 1.18, 95% CI 0.96-1.44) [9, 21, 22, 31]. Overall, subgroup analyses by various factors demonstrated that patients with PD have a higher risk to develop MI.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a statistical positive correlation between PD and MI. Patients with PD have approximately a 1-fold increase in risk for MI. Given the high prevalence of PD in population [32], this increase might mean a profound public health impact.

Several meta-analyses have reported that subjects with PD have higher odds and higher risks of developing cardiovascular diseases [33–38]. Teeuw et al pooled 25 studies on treatment of periodontitis and demonstrated intervention of PD improved the atherosclerotic profile [39], but the direct evidence of reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events associated with periodontitis treatment remains lacking. Further, a meta-analysis reported that patients with periodontitis compared to controls have increased arterial stiffness [39]. However, the only two interventional studies contradicted with each other on the effects of periodontal treatment on arterial stiffness [40]. Therefore, PD appears to be associated with increased risk of CVD, but the causal relation is still not well established.

Myocardial infarction is one of the most life-threating cardiovascular diseases. Some investigations mentioned the relationship between PD and MI, while dispute exists. In 1996, Joshipural KJ’s group followed up a cohort including 44119 males for 6 years and found no overall association between PD and fatal or non-fatal MI in this population [21]. This negative result was further echoed by some other prospective cohort studies [22, 23]. However, a large body of evidence showed there was an association between PD and MI. Very recently a large case–control study indicated that the risk of MI was significantly increased in patients with PD even after adjustment for confounding factors [15]. These disputes required further systemic analyses on the relation between MI and PD. However, to the best of our knowledge, no meta-analyses specified the relation between PD and MI.

In this study, we have showed an overall increased risk for MI in PD patients. The subgroup meta-analyses by study design showed that PD was associated with MI in both cross-sectional and case–control studies, while the relation in the cohort studies was marginal. Likewise, the subgroup analyses by country, PD exposure, participant number and study quality consistently showed an apparent increased risk of MI in PD subjects. Moreover, a marginal but non-significant increase of risk was present in male population. These non-significant findings exist in cohort studies and male participants might be attributed to the small number of studies included in the subgroup meta-analyses. Intriguingly, Rydén L group in their case–control study specified that the risk of a first MI was significantly increased in patients with PD. [15] However, most of the studies did not clarify the MI occurrence which presumably might be first ever MI. Renvert S et al also reported the relation between PD and recurrent MI [10]. First and recurrent MI differentiation would better illustrate the predication value of PD. Regarding limited data, the PD predication efficacy comparison between first and recurrent MI remains unknown.

Although not fully illustrated, several mechanisms were speculated to be involved in such a relation between PD and MI. The periodontal pathogen burden and its by-products might not only contribute to the development of atherosclerosis but also the rupture of atherosclerotic plaques and occurrence of MI. Dozens of literature has demonstrated that periodontal bacteria are detected in from atherosclerotic plaques. Ohki T et al. further suggested that three species of periodontal bacteria were present in the thrombi of patients with acute MI [41]. This finding suggested that periodontal bacteria might play a role in plaque inflammation and instability. Meanwhile, periodontal bacteria and the lipopolysaccharide from them could trigger inflammatory factor release, such as tumor necrosis factor α, interleukins, whose roles are well established in atherogenesis and rupture of developed lesions [42]. Further, C-reactive protein (CRP), a non-specific acute-phase factor participating in the systemic response to inflammation, helps to improve the risk prediction of cardiovascular events. Patients with PD also have increased serum levels of CRP relative to unaffected subjects [43]. The level of infection with periodontal pathogens is positively correlated with CRP level [44]. These evidence suggests that CRP might underlie the relation between PD and MI. In addition, platelet aggregation and thromboembolic events could be activated by periodontal pathogens themselves and many other cytokines [38].

Heterogeneity among studies was revealed in this analysis, although the relation between PD and MI has similar tendency in the overall and subgroup analysis. The significant heterogeneity was also reported in meta-analysis on PD and cardiovascular diseases [45, 46]. By nature, the diagnosis of PD was quite variable and included a series of parameters, such as attachment loss, bone loss pocket, probing depth, bleeding on probing, plaque index, gingival index, X-ray and microbiological results, teeth loss and the Russell periodontal index. Different PD assessment resulted in discrepancy when analyzing the relation between PD and MI. Renvert S’ group compared 5 PD parameters and their combination, founding that comprehensive PD data should be used in studies of associations between periodontitis and heart diseases [47]. Many other risk factors including age, smoking, and diabetes are common in both PD and MI. These factors could be taken into consideration as confounding factor. Different confounding factors were adjusted as demonstrated in Table1. This different adjustment could also affect the adjusted OR/RR when investigating the relation between PD and MI. Moreover, study design, study quality, number of participants and location were examined to find the sources of heterogeneity. The subgroup analysis showed these factors did not appreciably change the heterogeneity among studies. Further, sensitivity analyses showed no alterations to the pooled OR by omitting each study. Together, the significant heterogeneity should be considered when interpreting the results in this study, although the strong relation between PD and MI are observed.

Most of the studies that exclude for the meta-analysis in this study also supported a positive association between PD and MI. A population-based study showed periodontitis was associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiac events including MI occurrence [48]. Other studies also indicated that PD may be associated with MI in Turkish and Iran population [49, 50]. Vice versa, there was higher prevalence of edentulousness and advanced PD in the hospitalized MI group than that in the non-MI group [51]. A case–control study also showed MI patients exhibited an unfavorable dental chronic infection compared with healthy patients. These data from the other angle suggests an association between PD and MI.

Several limitation of this meta-analysis should be noted. First, limited by the nature of observational studies, the causality between PD and MI cannot be inferred from our findings. Second, as aforementioned, definitions for PD in each study included in the analysis were not identical. Although we set rules when extracting data, this discrepancy in the assessments for PD seemed not to be eliminated nor even decreased obviously. Additionally, the differences in the study design, population and criteria to measure the exposure may weaken the evidence and lead to considerable heterogeneity. Although further analysis were performed, the sources of the heterogeneity remained not clear. The meta-regression analysis might further explain the source of heterogeneity. For the paucity of the data, these analyses were not conducted. Finally, the concrete mechanisms to explain the PD and MI relation still need further investigation, though possible mechanisms were discussed above. Further prospective studies are warranted to establish the association between PD and MI, while it might also be helpful to confirm the relation with randomized, controlled interventional trials including medication to control the pain and inflammation and surgery to remove the inflamed tissue and reduce the bone damage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our meta-analysis yielded a statistically significant association between PD and MI. Subgroup analyses also confirmed the elevated risk for MI in PD subjects, although heterogeneity should be noted. More studies including large-scale prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials are warranted.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for healthcare research and quality

- CAL:

-

Clinical attachment loss

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MOOSE:

-

Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PD:

-

Periodontal disease

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RR:

-

Relative risk

References

Albandar JM, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Destructive periodontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988-1994. J Periodontol. 1999;70(1):13–29.

Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809–20.

You Z, Cushman M, Jenny NS, Howard G. Regards. Tooth loss, systemic inflammation, and prevalent stroke among participants in the reasons for geographic and racial difference in stroke (REGARDS) study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(2):615–9.

Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, Osinbowale O, Trevisan M, Levison ME, et al. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association?: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(20):2520–44.

Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, Rasi VP, Kesaniemi YA, Syrjala SL, et al. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298(6676):779–81.

Rutger Persson G, Ohlsson O, Pettersson T, Renvert S. Chronic periodontitis, a significant relationship with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(23):2108–15.

Cueto A, Mesa F, Bravo M, Ocana-Riola R. Periodontitis as risk factor for acute myocardial infarction. A case control study of Spanish adults. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40(1):36–42.

Andriankaja OM, Genco RJ, Dorn J, Dmochowski J, Hovey K, Falkner KL, et al. The use of different measurements and definitions of periodontal disease in the study of the association between periodontal disease and risk of myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2006;77(6):1067–73.

Andriankaja OM, Genco RJ, Dorn J, Dmochowski J, Hovey K, Falkner KL, et al. Periodontal disease and risk of myocardial infarction: the role of gender and smoking. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(10):699–705.

Renvert S, Ohlsson O, Pettersson T, Persson GR. Periodontitis: a future risk of acute coronary syndrome? A follow-up study over 3 years. J Periodontol. 2010;81(7):992–1000.

Holmlund A, Hedin M, Pussinen PJ, Lerner UH, Lind L. Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) a possible link between impaired oral health and acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148(2):148–53.

Samani MK, Jalali F, Ahadi SMS, Hoseini SR, Sattari FD. The relationship between acute myocardial infarction and periodontitis. Caspian J Intern Med. 2013;4(2):667–71.

Li P, He L, Sha YQ, Luan QX. Periodontal status of patients with post-acute myocardial infarction. Beijing da xue xue bao. 2013;45(1):22–6.

Kodovazenitis G, Pitsavos C, Papadimitriou L, Vrotsos IA, Stefanadis C, Madianos PN. Association between periodontitis and acute myocardial infarction: a case-control study of a nondiabetic population. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49(2):246–52.

Ryden L, Buhlin K, Ekstrand E, de Faire U, Gustafsson A, Holmer J, et al. Periodontitis Increases the Risk of a First Myocardial Infarction: A Report From the PAROKRANK Study. Circulation. 2016;133(6):576–83.

Yu YH, Chasman DI, Buring JE, Rose L, Ridker PM. Cardiovascular risks associated with incident and prevalent periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(1):21–8.

Holmlund A, Holm G, Lind L. Severity of periodontal disease and number of remaining teeth are related to the prevalence of myocardial infarction and hypertension in a study based on 4,254 subjects. J Periodontol. 2006;77(7):1173–8.

Bazile A, Bissada NF, Nair R, Siegel BP. Periodontal assessment of patients undergoing angioplasty for treatment of coronary artery disease. J Periodontol. 2002;73(6):631–6.

Buhlin K, Gustafsson A, Håkansson J, Klinge B. Oral health and cardiovascular disease in Sweden. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(3):254–9.

Parkar SM, Modi GN, Jani J. Periodontitis as risk factor for acute myocardial infarction: A case control study. Heart Views. 2013;14(1):5–11.

Joshipura KJ, Rimm EB, Douglass CW, Trichopoulos D, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Poor oral health and coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 1996;75(9):1631–6.

Howell TH, Ridker PM, Ajani UA, Hennekens CH, Christen WG. Periodontal disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease in U.S. male physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(2):445–50.

Dorn JM, Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Falkner KL, Hovey KM, Iacoviello L, et al. Periodontal disease and recurrent cardiovascular events in survivors of myocardial infarction (MI): the Western New York Acute MI Study. J Periodontol. 2010;81(4):502–11.

Willershausen I, Weyer V, Peter M, Weichert C, Kasaj A, Munzel T, et al. Association between chronic periodontal and apical inflammation and acute myocardial infarction. Odontology. 2014;102(2):297–302.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, Treadwell JR, Reston JT, Bass EB, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions--agency for healthcare research and quality and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(5):513–23.

Hu J, Dong Y, Chen X, Liu Y, Ma D, Liu X, et al. Prevalence of suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;61:78–89.

Walter SD, Cook RJ. A comparison of several point estimators of the odds ratio in a single 2 x 2 contingency table. Biometrics. 1991;47(3):795–811.

Senba T, Kobayashi Y, Inoue K, Kaneto C, Indue M, Toyokawa S, et al. The association between self-reported periodontitis and coronary heart disease - From my health up study. J Occup Health. 2008;50(3):283–7.

Brown LJ, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Periodontal status in the United States, 1988-1991: prevalence, extent, and demographic variation. J Dent Res. 1996;75 Spec No:672-683.

Leng WD, Zeng XT, Kwong JS, Hua XP. Periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease: An updated meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:469–72.

Khader YS, Albashaireh ZS, Alomari MA. Periodontal diseases and the risk of coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases: a meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2004;75(8):1046–53.

Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95(5):559–69.

Humphrey LL, Fu R, Buckley DI, Freeman M, Helfand M. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2079–86.

Beck JD, Offenbacher S. The association between periodontal diseases and cardiovascular diseases: a state-of-the-science review. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6(1):9–15.

Bahekar AA, Singh S, Saha S, Molnar J, Arora R. The prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease is significantly increased in periodontitis: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2007;154(5):830–7.

Teeuw WJ, Slot DE, Susanto H, Gerdes VE, Abbas F, D'Aiuto F, et al. Treatment of periodontitis improves the atherosclerotic profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(1):70–9.

Vidal F, Cordovil I, Figueredo CM, Fischer RG. Non-surgical periodontal treatment reduces cardiovascular risk in refractory hypertensive patients: a pilot study. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(7):681–7.

Ohki T, Itabashi Y, Kohno T, Yoshizawa A, Nishikubo S, Watanabe S, et al. Detection of periodontal bacteria in thrombi of patients with acute myocardial infarction by polymerase chain reaction. Am Heart J. 2012;163(2):164–7.

Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(9):2045–51.

Slade GD, Ghezzi EM, Heiss G, Beck JD, Riche E, Offenbacher S. Relationship between periodontal disease and C-reactive protein among adults in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(10):1172–9.

Dye BA, Choudhary K, Shea S, Papapanou PN. Serum antibodies to periodontal pathogens and markers of systemic inflammation. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(12):1189–99.

Blaizot A, Vergnes JN, Nuwwareh S, Amar J, Sixou M. Periodontal diseases and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis of observational studies. Int Dent J. 2009;59(4):197–209.

Martin-Cabezas Rodrigo SN. Petit Catherine, Agossa K´evimy, Gaertner S´ebastien, Tenenbaum Henri, Davideau Jean-Luc, et al. Association between periodontitis and arterial hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2016;180:98–112.

Renvert S, Ohlsson O, Persson S, Lang NP, Persson GR. Analysis of periodontal risk profiles in adults with or without a history of myocardial infarction. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31(1):19–24.

Chou SH, Tung YC, Lin YS, Wu LS, Lin CP, Liou EJ, et al. Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Treated Periodontitis: A Population-Based Follow-Up Study from Taiwan. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130807.

Emingil G, Buduneli E, Aliyev A, Akilli A, Atilla G. Association between periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2000;71(12):1882–6.

Amoian B, Maboudi A, Abbasi V. A periodontal health assessment of hospitalized patients with myocardial infarction. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2(2):234–9.

Wozakowska-Kaplon B, Wlosowicz M, Gorczyca-Michta I, Gorska R. Oral health status and the occurrence and clinical course of myocardial infarction in hospital phase: a case-control study. Cardiol J. 2013;20(4):370–7.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data and writing the manuscript has been conducted by staff of the Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China.

Availability of data and materials

Data were retrieved from articles found in PubMed, the Cochrane Library Databases and EMBASE, and summarized in Table 1.

Authors’ contributions

S. Xu and Z. Qin designed this study. S. Xu and X. Liu searched the databases and selected the studies according to the criteria and exclusion criteria. M. Song and Y Xiong helped develop search strategies. S. Xu, Y. He and M. Song extracted data and conducted the statistics. Z. Qin wrote the draft of the paper. All authors participated in the process of discussion, review, and revision of the paper.

Competing interests

None.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Search Strategy. (PDF 66 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Quality scores of case–control and cohort studies using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. (PDF 37 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Quality scores of cross-sectional studies using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Scale. (PDF 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, S., Song, M., Xiong, Y. et al. The association between periodontal disease and the risk of myocardial infarction: a pooled analysis of observational studies. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17, 50 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0480-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0480-y