Abstract

Background

Few studies have evaluated muscle strength in COVID-19 ICU survivors. We aimed to report the incidence of limb and respiratory muscle weakness in COVID-19 ICU survivors.

Method

We performed a cross sectional study in two ICU tertiary Hospital Settings. COVID-19 ICU survivors were screened and respiratory and limb muscle strength were measured at the time of extubation. An ICU mobility scale was performed at ICU discharge and walking capacity was self-evaluated by patients 30 days after weaning from mechanical ventilation.

Results

Twenty-three patients were included. Sixteen (69%) had limb muscle weakness and 6 (26%) had overlap limb and respiratory muscle weakness. Amount of physiotherapy was not associated with muscle strength. 44% of patients with limb weakness were unable to walk 100 m 30 days after weaning.

Conclusion

The large majority of COVID-19 ICU survivors developed ICU acquired limb muscle weakness. 44% of patients with limb weakness still had severely limited function one-month post weaning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The rate of intensive care unit admissions due to coronavirus (COVID-19) infections was very high and a large proportion of these patients required invasive ventilation [1]. Evidence from studies carried out worldwide shows that patients who undergo invasive ventilation in ICU have a high risk of developing respiratory and limb muscle weakness (50% prevalence) [2]. It is therefore reasonable to expect that a large proportion of COVID-19 ICU survivors will develop such weakness. Guidelines from an international team of expert physiotherapist researchers and clinicians recommend early physiotherapy in the ICU to prevent ICU-acquired weakness [3].

Although a large number of studies into various aspects of COVID-19 have been published [4], to our knowledge, few studies have evaluated muscle strength in COVID-19 ICU survivors [5]. There is also a paucity of data relating strength to physiotherapy interventions carried out during the period of mechanical ventilation (MV). The primary aim of this study was to report the prevalence of limb and respiratory muscle weakness in COVID-19 ICU survivors. The secondary aims were to analyse variables associated with muscle weakness.

Method

We conducted a retrospective, observational study in two centres, each with a 30 bed ICU. In accordance with current French legislation, written informed consent was unnecessary for this study. Data were collected and treated in accordance with the French Institutional Review Board (CNIL ID-number n°2,220,110) and in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients with laboratory confirmed COVID-19 infection who were intubated for at least 24 h and were hospitalized between the 16th of March and the 15th of May 2020 were included.

In both centres, all patients received physiotherapy. In center 1: rehabilitation started when administration of neuromuscular blockers ceased. Quadriceps electrical muscle stimulation if the patient could not respond to simple commands. Active mobilization was started in bed once the patient could follow commands. Sitting over the edge of the bed was initiated when the patient’s haemodynamic condition was stable. Inspiratory muscle training (IMT) was initiated when the patient had shifted to a pressure support ventilation mode.

In center 2: rehabilitation started with passive mobilisation when the patient was still under neuromuscular blockers. Active mobilization was started in bed once the patient could follow commands. Sitting over the edge of the bed was initiated when the patient’s haemodynamic condition was stable. Electrical muscle stimulation and inspiratory muscle training were not performed.

Respiratory and limb muscle strength were measured at the time of extubation if the patient was sufficiently alert and cooperative to respond to instructions. Three measurements of maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP) were carried out and the best result was used in the analysis. Respiratory weakness was defined as an MIP ≤ 30cmH2O [6]. Limb muscle strength was evaluated using the MRC scale with weakness defined as a score ≤ 48/60. Patients’ functional status on discharge from ICU was evaluated with the ICU mobility scale (IMS).

Patients were contacted by telephone 30 days after mechanical ventilation weaning and asked if they could walk more than 100 m.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as counts and percentages for categorical data, and means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges, according to the distribution, for continuous variables.

Patients’ baseline characteristics were compared between groups with limb weakness and no weakness using a Student t test or a Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate, for continuous variables and using a Chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. Significative variables were included in a multiple regression analysis model. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). A two-tailed p value of 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

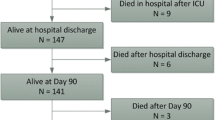

During the study period, 89 patients with confirmed COVID-19 were admitted to ICU in both centres, and 65 required invasive MV. Twenty-four patients died before weaning and the evaluation could not be carried out for 18 patients during the weaning process because of neurological disorders, agitation or lack of staff to perform the evaluations, thus data from 23 patients were analysed.

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1 shows individual classifications of the patient according to their strength. Of 23 patients, 16 (69%) had limb muscle weakness and 6/23 (26%) had overlap (limb and respiratory muscle weakness) weakness [7]. Limb muscle weakness was significantly associated with the number of days spent in a prone position, the use of catecholamines, and the number of days under MV (Table 1), particularly with the use of assist-control ventilation (10.6 ± 6.3 vs. 4.8 ± 3.6 days; p = 0.03). Table 2 shows the physiotherapy intervention performed during mechanical ventilation. Passive range of motion, in-bed strengthening, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), inspiratory muscle training and out-of-bed verticalization was the commons physiotherapy intervention. The number of sessions of physiotherapy was not associated with higher muscle strength. Some inspiratory muscle training sessions induced adverse events with rapid resolution (bradycardia less than 50 bpm). Multiple regression analysis showed that muscle weakness was only independently associated with the number of days under MV (p = 0.005) (See Table 3). There was a statistically significant difference between the ICU mobility scale scores of the two groups. Patients with muscle weakness had lower IMS scores (4.3 ± 1.5 vs. 8 ± 0.6; p < 0.001).

Briefly, patients in the Limb weakness group acquired the standing position while the patients in the no weakness group could walk at least 5 m away from the bed/chair, assisted by 1 person.

Of the patients with limb muscle weakness (n = 16), 7 (44%) were unable to walk 100 m 30 days after weaning, however 6 of them could walk shorter distances. All the patients who did not have limb muscle weakness were able to walk 100 m or more.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that a high proportion of COVID-19 survivors developed ICU acquired muscle weakness, despite early physiotherapy, and 44% were unable to walk 100 m 30 days post discharge.

Despite receiving early, evidence-based physiotherapy with therapists who were all experienced in ICU physiotherapy [8, 9], a high proportion of patients developed muscle weakness. The rate of limb muscle weakness found in this cohort of patients was also higher than in patients without COVID-19 [10], which could be due to the longer duration of MV. The higher number of physiotherapy sessions in the Limb weakness group is also due to the longer duration of mechanical ventilation in that group.

The incidence of ICU muscle weakness in this cohort was similar to that found by Van Aerde et al. [5]. These findings highlight the necessity to try to (1) decrease the use of invasive mechanical ventilation, (2) increase early rehabilitation intensity for the prevention of ICU acquired weakness in patients who undergo long periods of MV, (3) anticipate the need for rehabilitation after ICU, and (4) enhance post-ICU follow-up to monitor weakness and its long-term impact [11].. Despite our results, it is possible that early physiotherapy intervention decreased the severity of weakness. Post-discharge, patients who required further physiotherapy continued with outpatient (or home) physiotherapy, and it is encouraging to note that only one patient was unable to walk 30 days later, suggesting a potential for recovery of walking in COVID-19 ICU survivors.

Surprisingly, the rate of patients with respiratory muscle weakness was very low and was not associated with any of the other variables analysed. This could be related to the small size of the cohort and the fact that pressure support mode was used for around 40% of MV time. The recruitment of the respiratory muscles for this duration is known to reduce the risk of respiratory muscle weakness [12].

Limitations

Our study design and the low sample size induced some limitations. We couldn’t report precisely the time return at a good functional status and the one-month functional evaluation lacked specificity. Firstly, we did not evaluate upper-limb function. Secondly, the evaluation is not a validated functional test such as the six-minute walk test or the one-minute sit to stand test. In view of the health crisis, it was not possible for patients to return to hospital for follow-up evaluations. We therefore chose this simple self-evaluation and used the distance proposed in the MMRC dyspnoea scale that indicates that patients who walk less than 100 m are unlikely to go out of their homes and are severely limited in their daily activities [13]. Further work is necessary to evaluate the functional consequences in the longer-term using more specific and complete measures.

Finally, in this study, we did not evaluate chest physiotherapy techniques to improve respiratory function in patients with Covid-19 [14, 15]. However, it is important to specify the importance of techniques that can improve respiratory function, reduce the risk of failure to wean from ventilation and to optimise the return to functional independence [16, 17].

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that a high majority of COVID-19 ICU survivors developed ICU acquired limb muscle weakness due to the long duration of MV. Early physiotherapy was not sufficient to prevent this from occurring and, in this small study, 44% of patients with limb weakness still had severely limited function one-month post discharge. However, the majority of patients were in the process of recovering function.

Availability of data and materials

Data were available by contacting corresponding author medrinal.clement.mk@gmail.com

References

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62.

Medrinal C, Combret Y, Hilfiker R, Prieur G, Aroichane N, Gravier F-E, et al. ICU outcomes can be predicted by non invasive muscle evaluation: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:1902482.

Thomas P, Baldwin C, Bissett B, Boden I, Gosselink R, Granger CL, et al. Physiotherapy management for COVID-19 in the acute hospital setting: clinical practice recommendations. J Physiother. 2020;66:73–82.

Du Y, Tu L, Zhu P, Mu M, Wang R, Yang P, et al. Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan. A retrospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1372–9.

COVID-19 Consortium, Van Aerde N, Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Gosselink R, Hermans G. Intensive care unit acquired muscle weakness in COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2083–5.

Medrinal C, Prieur G, Frenoy É, Robledo Quesada A, Poncet A, Bonnevie T, et al. Respiratory weakness after mechanical ventilation is associated with one-year mortality - a prospective study. Crit Care. 2016;20:231.

Medrinal C, Prieur G, Frenoy É, Combret Y, Gravier FE, Bonnevie T, et al. Is overlap of respiratory and limb muscle weakness at weaning from mechanical ventilation associated with poorer outcomes? Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:282–3.

Fossat G, Baudin F, Courtes L, Bobet S, Dupont A, Bretagnol A, et al. Effect of in-bed leg cycling and electrical stimulation of the quadriceps on global muscle strength in critically ill adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:368–78.

Medrinal C, Combret Y, Prieur G, Robledo Quesada A, Bonnevie T, Gravier FE, et al. Comparison of exercise intensity during four early rehabilitation techniques in sedated and ventilated patients in ICU: a randomised cross-over trial. Crit Care. 2018;22:110.

Vanhorebeek I, Latronico N, Van den Berghe G. ICU-acquired weakness. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:637–53.

Carda S, Invernizzi M, Bavikatte G, Bensmaïl D, Bianchi F, Deltombe T, et al. The role of physical and rehabilitation medicine in the COVID-19 pandemic: the clinician’s view. Ann Phys Rehab Med. 2020;63:554–6.

Futier E, Constantin J-M, Combaret L, Mosoni L, Roszyk L, Sapin V, et al. Pressure support ventilation attenuates ventilator-induced protein modifications in the diaphragm. Crit Care. 2008;12:R116.

Williams N. The MRC breathlessness scale. Occup Med. 2017;67:496–7.

Lazzeri M, Lanza A, Bellini R, Bellofiore A, Cecchetto S, Colombo A, et al. Respiratory physiotherapy in patients with COVID-19 infection in acute setting: a position paper of the Italian Association of Respiratory Physiotherapists (ARIR). Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020;90(1).

Battaglini D, Robba C, Caiffa S, Ball L, Brunetti I, Loconte M, et al. Chest physiotherapy: an important adjuvant in critically ill mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2020;282:103529.

Abdullahi A. Safety and efficacy of chest physiotherapy in patients with COVID-19: a critical review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:454.

Simonelli C, Paneroni M, Fokom AG, Saleri M, Speltoni I, Favero I, et al. How the COVID-19 infection tsunami revolutionized the work of respiratory physiotherapists: an experience from northern Italy. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020;90(2).

Acknowledgments

The Authors tanks the ICU medical and paramedical teams and Johanna Robertson, medical translator for her work.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guarantor: Clément Medrinal. Study concept and design: Medrinal, Prieur, Lamia, Combret, Fossat. Acquisition of data: All authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: Medrinal, Prieur, Bonnevie, Gravier, Mayard, Desmalles, Smondack, Lamia, Combret, Fossat. Drafting of the manuscript: Medrinal, Prieur, Combret, Fossat. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

We confirm that all experimental protocols were approved by the Groupe Hospitalier du Havre, the CHR Orléans and The French « Comission d’informatique et des Libertés » (CNIL).

The French « Comission d’informatique et des Libertés » (CNIL: register study-ID n°2220110) waived the requirement of the informed consent for the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Medrinal, C., Prieur, G., Bonnevie, T. et al. Muscle weakness, functional capacities and recovery for COVID-19 ICU survivors. BMC Anesthesiol 21, 64 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01274-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01274-0