Abstract

Background

Carbohydrate accumulation of photosynthetic organs, mainly leaves, are the primary sources of grain yield in cereals. The flag leaf plays a vital role in seed development, which is probably the most neglected morphological characteristic during traditional selection processes.

Results

In this experiment, four flag leaf morphological traits and seven yield-related traits were investigated in a DH population derived from a cross between a wild barley and an Australian malting barley cultivar. Flag leaf thickness (FLT) showed significantly positive correlations with grain size. Four QTL, located on chromosomes 1H, 2H, 3H, and 5H, respectively, were identified for FLT. Among them, a major QTL was located on chromosome 3H with a LOD value of 18.4 and determined 32% of the phenotypic variation. This QTL showed close links but not pleiotropism to the previously reported semi-dwarf gene sdw1 from the cultivated barley. This QTL was not reported before and the thick leaf allele from the wild barley could provide a useful source for improving grain yield through breeding.

Conclusions

Our results also provided valuable evidence that source traits and sink traits in barley are tightly connected and suggest further improvement of barley yield potential with enhanced and balanced source and sink relationships by exploiting potentialities of the wild barley resources. Moreover, this study will provide a novel sight on understanding the evolution and development of leaf morphology in barley and improving barley production by rewilding for lost superior traits during plant evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is one of the oldest cultivated cereals and is widely distributed in all agricultural regions [1]. Barley is also an important cereal which fulfils the increasing demand of raw materials for livestock food production, fermentable material for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods [2,3,4]. Individual barley grain yield is the cumulative result of both source and sink strength for photoassimilates and nutrients over the course of seed development, where the source potentially reflects photosynthetic capacity, and the sink shows the potential capacity to accumulate photosynthate [5]. Strengthening source and sink and modifying sink-source relations could optimise crop yield. This is evidenced by the changes in source/sink of several crops during their domestication and transformation into modern cultivars, including rice, wheat, and barley [6,7,8].

Sources and sinks for both carbon and nitrogen are key components of plant productivity and yield, source–sink interactions are regulated by feedback, feedforward and crosstalk mechanisms [9, 10]. As the most important resource tissue, plant leaves are responsible for light interception, photosynthesis, and assimilate storage thus play vital roles in crop yield [11], determining over 50% carbohydrate accumulation in grains [12,13,14]. Leaf shapes arise within a developmental context that constrains both their evolution and environmental plasticity [15]. A leaf represents an investment on the part of a plant with the return being reflected by net dry-mass gain per unit leaf area. A leaf return will stop when photosynthesis no longer exceeds the costs of leaf respiration and root and stem activity to support the leaf’s photosynthesis [16].

A leaf’s physical strength depends on both its thickness and its tissue density. Among all the morphological traits of leaves, flag leaf thickness was reported to be positively correlated with the single-leaf net photosynthetic rate (Pn) in determining grain yield in rice [17, 18] as thicker leaves have higher chlorophyll (Chl) contents, which are the main pigments involved in light capture for photosynthesis [19]. Leaf thickness may also contribute to improved leaf angle and curvature [20]. Rice varieties with high yield potential and greater responsiveness to applied nitrogen (N) exhibited thick leaves along with short sturdy stems [21]. Positive correlations have also been reported between leaf thickness and panicle traits, such as panicle length, grain density, grain weight per panicle, and the number of spikelets per panicle in rice [22]. Therefore, leaf thickness could be considered as an important index in high-yielding cultivars breeding [22]. Plant leaf area, which is composed of leaf length and width, significantly influences plant growth, development, yield, and quality by affecting photosynthetic assimilates [23,24,25,26,27]. Flag leaf length and width in wheat are positively correlated with yield components, such as spike number per plant and tiller number per plant [28, 29].

Crop yield could be dissected into several components: number of ears per ha, grain number per ear and thousand-grain weight. So far, many genes or QTL related to grain yield and yield components have been reported in barley [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. However, relatively fewer QTL were reported in barley for net photosynthetic rate and leaf morphological traits [38,39,40,41] compared with rice [42,43,44,45,46] and wheat [28, 29, 47,48,49,50,51]. The association between leaf morphological traits and yield potential has not been fully discovered in barley.

Crop domestication is one of the key approaches leading to currently cultivated crops [52]. The process of domestication, i.e. from wild barley to cultivated barley, has resulted in gene loss or changes in gene regulation/activity (i.e. via variations in the coding sequence) which imposes constraints on our ability to further improve cultivated varieties [52]. Breeders have been focusing on morphological characteristics for sink-related traits, such as grain size, with less efforts on source-related traits, in particular leaf thickness which is hard to select in the field. Thus the thicker leaf alleles could be easily lost or neglected during domestication and selection. Leaf shape could be seen as a functional response of plants to changes in the environment, understanding the potential adaptive value of leaf shape, and the genetic and molecular approaches to manipulate it will prove to be invaluable in breeding the next generation of crops and sustainably maintaining biodiversity and crop yield in future climates [15].

Our preliminary results showed that a wild barley accession, SYR01 (Hordeum spontaneum), showed much thicker flag leaf than the cultivated barley, Gairdner (Hordeum vulgare L.). Thus, the DH (doubled haploid) population from the cross between SYR01 and Gairdner was selected to identify QTL and linked molecular markers for flag leaf thickness and their potential links with other flag leaf traits, plant height and grain size. As it is too hard to select leaf thickness in the field, these markers can assist in selecting thicker leaf thus improve the source of cultivated barley.

Result

Phenotypic variations and correlations

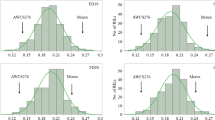

Gairdner had a significantly longer, wider leaf and larger flag leaf area than SYR01 (Fig. 1). In contrast, SYR01 had a much thicker flag leaf than Gairdner (Fig. 1). All flag leaf traits showed large variations among DH lines across different years or trials, displaying continuous and near normal distribution (Fig. 1). Similar performances were also found in other traits (Supplementary Figures S1, S2). SYR01 showed taller plants, longer grains, while lower PL (panicle length), GWP (grain weight per panicle), TGW (thousand grain weight), GW (grain width), GT (grain thickness) and ASA (average seed area) than Gairdner (Supplementary Figures S1, S2). Field trials showed much thicker, longer and wider flag leaf than the glasshouse trials (Fig. 1) due to prolonged growth period in the field trials, suggesting a significant environmental effect on leaf development.

From the average values of 2020 field and 2020 glasshouse trials, FLT (flag leaf thickness) showed weak but significant correlation with FLL (flag leaf length, r = 0.25, P < 0.01) and FLA (flag leaf area, r = 0.20, P < 0.05). FLT had a closer correlation with grain size than FLL and FLW (flag leaf width) while FLL and FLW were significantly correlated with PL and GWP (Fig. 2). All these leaf traits were highly inheritable with narrow-sense heritability ranging from 0.70 for FLT to 0.81 for FLL (Supplementary Table S1).

Correlations between flag leaf-related traits and yield-related traits. The number in the middle of the cell is the correlation coefficient; ‘*’, ‘**’ and ‘***’ refer to significant correlations (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001). FLT, flag leaf thickness; FLL, flag leaf length; FLW, flag leaf width; FLA, flag leaf area; PL, panicle length; GWP, grain weight per panicle; TGW, thousand grain weight; GL, grain length; GW, grain width; GT, grain thickness, ASA, average seed area

QTL for flag leaf traits

QTL identified for flag leaf-related traits were widely distributed on all barley chromosomes (Table 1; Fig. 3). One major QTL for FLT was identified on chromosome 3H (Qflt-3H) with a LOD value of 18.4, determining more than 30% of the phenotypic variation. Three minor QTL (Qflt-1H, Qflt-2H, Qflt-5H) for FLT were located on chromosomes 1H, 2H, and 5H, respectively, determining 5.8 to 7.6% of the phenotypic variation. The wild barley contributed thicker leaf alleles for all the QTL. Five QTL (Qfll-1H, Qfll-2H, Qfll-3H, Qfll-4H, Qfll-6H) were identified for FLL, determining 5.8 to 17.9% of the phenotypic variation. Qfll-2H was located at a similar position to a minor QTL for FLT (Qflt-2H). Two QTL on chromosome 2H (Qflw-2H.1, Qflw-2H.2) were identified for FLW, determining 15.7 and 10.3% of the phenotypic variation, respectively. FLA was calculated from FLL and FLW, and the major QTL for FLA was located at the same positions of these QTL for FLL and/or FLW. These four QTL determined more than 50% of the phenotypic variation. At the genetic map position of 50–80 cM on chromosome 2H, QTL for all the flag leaf traits, FLT (Qflt-2H), FLL (Qfll-2H), FLW (Qflw-2H.1), and FLA (Qfla-2H), were identified (Table 1). This region is around the centromere. Qflt-3H, Qfll-4H, and Qfla-2H were identified in both field trials and glasshouse trials.

QTL for grain size, PL and PH

Five QTL for PL were identified on chromosomes 1H, 2H, 3H, 4H, and 5H, respectively, explaining a total of 50% of phenotypic variation (Table 1). Qpl-1H and Qpl-2H were located at similar positions to two QTL (Qflt-1H, Qflt-2H) for FLT. Two QTL for TGW, GL, and GT, and three QTL for GW, and ASA were identified respectively (Table 1). The interval of the major QTL for GL (Qgl-1H) overlapped with Qtgw-1H, locating at similar positions to Qasa-1H and Qfla-1H. The allele from the wild parent SYR01 increased TGW, GL and ASA. The major QTL for TGW, Qtgw-6H, was located at a similar position to QTL for GW and ASA with Gairdner allele contributing the higher values. Qgl-3H for GL was located at a similar position to Qasa-3H for ASA on 3H. Qgw-4H for GW and Qgt-4H for GT are located at similar positions on 4H.

Discussion

Usefulness of FLT QTL

Morphological traits of flag leaf play important roles in determining crop grain yield and biomass, contributing a significant proportion of “the source” during grain filling stage. Many QTL have been reported for flag leaf length, width, and area [38, 40, 41]. These QTL are distributed on chromosomes 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, 6H, and 7H. Our results also identified QTL for these traits on all the chromosomes (Fig. 3). According to the marker information in our study, Qfll-2H (55.7‒65.5 cM) is in similar regions to qFLL2-2 and qFLA2-2 for FLL and FLA, respectively, reported by Du et al. [38]. Qflt-2H (52.8‒73.7 cM), Qflw-2H.1 (55.7‒67.1 cM) and Qfla-2H (56.7‒58.5 cM) for FLT, FLW and FLA, respectively, were also located in this region. Qfla-5H (51.8‒96.5 cM) for FLA in our study was likely the same locus to the QTL qFW5.1 (44.1‒46.4 cM) for FLW reported earlier [41]. In a previous study, QTL “D1Q1FLL2H”, “D1Q3FLL2H” and “D2Q4FLL2H” for FLL [40] coincided with Qflw-2H.2 (101.0‒139.2 cM) for FLW identified in our study. Zheng et al. [53] recently reported some QTL for FLT but the major QTL was different that identified in our study and the allele for increasing leaf thickness is from a cultivated barley. In this study, we have identified four QTL for FLT. The major one on 3H (631.9‒641.7 Mb) overlapped a semi-dwarf gene, sdw1(chr3H: 634,077,598–634,081,600) [54]. Our mapping results from this population also indicated a single major QTL, Qph-3H (R2 = 0.63), for plant height. This QTL was also located on 3H at a physical position of 633.98 Mb (72.0 cM), the same position of Qflt-3H for FLT. To further investigate the relationship between flag leaf thickness and plant height, we used plant height as a covariate to re-analyse QTL for FLT and the LOD value of Qflt-3H decreased from 16.91 to 6.33 and R2 reduced from 31.6 to 10.2% (Fig. 4). This suggests a close linkage between plant height and FLT. This is confirmed by the significant correlation between flag leaf thickness and plant height (r = 0.51) (Supplementary Figure S3a). However, when we grouped all the lines according to plant height, wide variations in FLT were shown in each group. For example, in the group with plant height between 85 and 95 (most likely to have the semi-dwarf gene), the FLT ranged from 220 to 320 (Supplementary Figure S3b). Therefore, this thick leaf QTL can be combined with the dwarf gene in breeding programs.

Based on correlation analysis, flag leaf thickness had significant positive correlations with grain weight, grain length, and seed area (Fig. 2). When using FLT as covariates, Qpl-3H, Qgl-3H, and Qasa-3H became insignificant. All results demonstrated the significant contribution of flag leaf thickness to yield-related traits in barley.

Candidate genes for FLT

Leaf thickness scaled with cell sizes, cell wall thicknesses and the thicknesses of component mesophyll tissues, specifically with the size of palisade mesophyll cells [55, 56]. Increased palisade cell height leads to improved uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) into mesophyll cells, and improved photosynthesis in thick leaves was witnessed [57]. Similarly, another study in the Arabidopsis Cvi ecotype found increased palisade mesophyll cell length contributed to increase of leaf thickness [58].

The QTL cluster regions of Qflt-2H and Qflt-3H not only affected the morphology of flag leaf but also had a positive effect on grain yield-related traits. From the annotation database (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/downloads/barley/), a gene that encodes LONGIFOLIA ½ protein (HORVU.MOREX.r3.2HG0126960.1 (108, 708, 757˗108, 713, 879, Morex V3, 2021)) were found within the interval of Qflt-2H on chromosome 2H. Previously, a cell wall invertase gene GIF1 (OsCIN2) for rice has been reported to determine grain-filling, which also contributes to seed development. In Arabidopsis, LONGIFOLIA1 and LONGIFOLIA2 are two homologous genes, and regulate leaf morphology by positively promoting longitudinal polar cell elongation [59]. HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0307040 (563, 634, 754˗563, 636, 989, Morex V3, 2021)) on chromosome 3H, encodes NAC domain proteins, which are associated with secondary wall thickening in Arabidopsis [60, 61]. Secondary walls also have specialized functions in determining pollen release from anther, and fiber elongation in seed trichomes [60, 62]. Therefore, HORVU.MOREX.r3.2HG0126960 and HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0307040 have potential impacts on FLT and seed development. Other genes, such as HORVU.MOREX.r3.2HG0126390 (Gibberellin receptor GID1A), HORVU.MOREX.r3.2HG0127670 (Vegetative cell wall protein gp1), and HORVU.MOREX.r3.3HG0308590 (SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family) within QTL intervals of Qflt-2H and Qflt-3H are listed in Supplementary Tables S2 and 3, respectively.

Improving barley production by rewilding for lost superior traits

Wild barley has been reported to contain great genetic variation which provides valuable genetic resources for the improvement of cultivated barley [63,64,65]. During the process of domestication for selected agronomic traits many of the inherited traits, in particular, biotic and abiotic stress tolerance, may have been weakened or lost [52]. Barley is one of the major crops with many lost traits during domestication through artificial selection by breeders to meet human needs. Identification of these “missing” beneficial genes/alleles in wild barley species would provide promising genetic resources for barley breeding in the future. Recent research have paid more attention to discovering biotic and abiotic stress tolerance genes from wild relatives [66, 67] which have been successfully used in breeding programs [68]. Domestication also caused the loss of many morphological traits, such as leaf thickness, which are hard to select based on field performance. The relationship between leaf morphology and climate can evolve repeatedly in response to similar environments [15]. Results from our preliminary screening of 700 barley genotypes also supported the hypothesis with most of the 30 genotypes that have the thickest flag leaves (over 310 μm) being wild barley of landraces. In contrast, the FLT of commercial varieties was around 250 μm with several of them being around 200 μm (Supplementary Table S4). However, some wild barley type may also have much thinner flag leaves phenotypes. A recent report showed that the FLT of a wild barley AWCS276 was less than 150 μm [53].

During the process of selection under resource-poor environments, seedlings of species or ecotypes with greater leaf dry mass per unit area will be chosen for longer leaf longevity, rather than selection acting on growth rates themselves, such as internode length [69]. Even when grown under favourable conditions, the plants will keep low growth rates [70]. Species with higher leaf mass per leaf area (LMA) have thicker laminas, veins that protrude more, higher tissue density, or combinations of these [71, 72]. High-LMA species tend to achieve a longer average leaf lifespan in a variety of habitats [16]. Thicker, tougher leaves are the most common and general-purpose of plants defence [73]. However, long leaf lifespan may also be correlated with greater relative allocation to tannins, phenols, or other defensive compounds [74].

Although QTL have recently been reported, genes regulating FLT in barley have not been identified. The identification of the genes can greatly facilitate crop development [22, 53, 57]. In this study, we identified four QTL for flag leaf thickness with all the alleles for increasing leaf thickness being from the wild accession. Pan-genomics which contains multiple high-quality sequences to show genetic diversity is now widely used in crops, including rice [75, 76], wheat [77], barley [78], soybean [79], and maize [80]. However, barley pan-genomic studies so far have been limited mostly to cultivated accessions, with only a few wild species [78, 81]. Wild species as sources of novel genes now present great potential for crop improvement by reintroducing into modern cultivars [52]. The candidate genes for Qflt-2H and Qflt-3H were used to blast the recently released barley pan-genome [78] at IPK barley blast server (http://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/barley_ibsc/). One of them, HORVU2Hr1G031980, was only found in the Morex reference genome rather than other wild or landrace barley varieties. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the exploration and mining of favourable alleles in wild barley resources, including these alleles to improve leaf traits thus producing a better trade-off between sink and source.

In conclusion, for the first time a major QTL was identified for flag leaf thickness with the thick leaf allele from a wild barley accession, which has been lost during evolution. The introduction of the allele to cultivated barley could have a potential in significantly increasing grain yield by improving source for grain filling. It also presents a great opportunity for scientists to conduct their functional studies of leaves by incorporating genetic and molecular approaches.

Materials and methods

Plant material

A barley DH population consisting of 155 lines was derived from a cross between Australian malting barley cultivar Gairdner (Hordeum vulgare L.) (two-rowed and short stature and Syrian wild barley SYR01 (Hordeum spontaneum)(two-rowed and tall plant) obtained from China. The population was constructed by the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, University of Tasmania.

Trials and trait measurements

Field trials were conducted at Mt Pleasant Laboratory in Tasmania, Australia (147°08’E, 41°280’S). In the field condition, fifteen seeds of each line were sown in a 0.6 m row with a row spacing of 0.25 m on 20 April 2019 and 25 April 2020. The field management followed the local farmers’ practices. In the glasshouse condition, five seeds of each line were sown in a 2-L pot filled with commercial potting mixture on 10 May 2020, at a spacing of 0.2 m between each pot. All the trials were carried out following a randomized complete block design with three replications. At the full-ripe stage, ten main panicles of each line were collected from field trials in both 2019 and 2020. Then the seeds were used for measuring thousand grain weight (TGW, g), grain length (GL, mm), grain width (GW, mm), grain thickness (GT, mm), and average seed area (ASA, mm2) by using the stand-alone digital image analyser with inbuilt software for image analysis in 2019 and 2020. Grains weight per panicle (GWP, g) was subsequently calculated. Flag leaf thickness (FLT, µm) was measured by a non-destructive leaf thickness instrument after anthesis in both glasshouse and the field in 2020, following the method previously described [22]. Taking the main vein as the vertical centre line of the blade, we measured the thickness of the left (x1) and right (x2) side of the middle part of the leaf blade and calculated the value of (x1 + x2)/2 as the thickness of the leaf blade. Flag leaf length (FLL, cm), width (FLW, cm) and panicle length (PL, cm) of the same plants were also measured. We followed the equation FLA = 0.69 × FLL × FLW to calculate the flag leaf area (FLA, cm2) [27]. Plant height (PH, cm) was measured from soil surface to the top of the spike excluding the awns in the field in 2019 and 2020.

Statistical analysis

The narrow-sense heritability (h2) was estimated as h2 = Vg/ (Vg +Vgei/s + Ve/sr), where Vg, Vgei, and Ve are the variance contributed by genotype, genotype-by-environment interaction, and residual error, respectively, while s is the number of environments and r is the number of replicates. The best linear unbiased predictions (BLUPs) for sink and source characteristics of each line across different environments were calculated using mixed linear models in the R package ‘lme4’ [82]. Then, the mean value of BLUPs of each line were used for statistical analysis and QTL mapping. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed with the R package ‘Hmisc’.

Genotyping and QTL mapping

Genomic DNA of each line was extracted and purified from approximately 100 mg leaf tissue via a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Murray and Thompson 1980). Whole genome diversity array technology (DArT) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping based on the 2017 Morex barley reference genome assembly were conducted by Diversity Arrays Technology (Canberra, Australia; https://www.diversityarrays.com). A total of around 22,000 DArT markers and 13,000 SNPs evenly distributed on the seven barley chromosomes were used to genotype the parents and 155 DH lines (Supplementary Figure S4). After filtering out low-quality markers (missing rate ≥ 10%) and those showing non-polymorphic in the two parents or progenies, a set of 8,334 DArT markers and 4,485 SNPs were generated. Then, the 12,819 markers were screened for similarities to remove redundant markers, and significantly distorted (P < 0.01) markers were also removed. Finally, 5052 markers were used for genetic map construction [64, 66] and QTL mapping. Genetic and physical positions of markers were aligned with the 2017 Morex barley reference genome assembly [83] as well as the most recent assembly [84] (Figure S5) using 2H as an example.

MapQTL 6.0 [85] was used for QTL analysis. The procedures of QTL detection have been well described before [86]. Briefly, the interval mapping (IM) function was applied for initial QTL scanning. A QTL was claimed to be significant at a LOD value higher than 3.0. Then the approximate multiple QTL model (MQM) was used for genetic background control. The percentage of total phenotypic variance explained by each QTL (R2) and the additive effect was obtained using the restricted MQM (rMQM) function. Interval of each QTL was calculated as the 95% confidence interval (1 LOD drop-off). MapChart 2.32 [87] was used for the graphical representation of linkage groups and QTL locations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. Original phenotypic data, genotypic data and molecular map file are included in additional files. Sub-section of all DH lines can be obtained from the corresponding author, Prof Meixue Zhou, TIA, University of Tasmania, under Material Transfer Agreement.

References

Newton A, Flavell A, George T, Leat P, Mullholland B, Ramsay L, et al. Crops that feed the world 4. Barley: A resilient crop? Strengths and weaknesses in the context of food security. Food Secur. 2011;3:141–78.

Collins HM, Burton RA, Topping DL, Liao M, Bacic A, Fincher GB. Review: Variability in fine structures of noncellulosic cell wall polysaccharides from cereal grains: potential importance in human health and nutrition. Cereal Chem. 2010;87(4):272–82.

Ullrich S: Barley: Production, Improvement, and Uses. In.; 2011: 3-13.

Newman CW, Newman RK. A brief history of barley foods. Cereal Foods World. 2006;51:4–7.

Venkateswarlu B, Visperas RM. Source-sink relationships in crop plants; 1987.

Zhang H, Tan G, Xue Y, Liu L, Yang J. Changes in grain yield and morphological and physiological characteristics during 60-year evolution of Japonica rice cultivars in Jiangsu. Zuo Wu Xue Bao. 2010;36(1):133–40.

Charmet G. Wheat domestication: Lessons for the future. C R Biol. 2011;334(3):212–20.

Wacker L, Jacomet S, Körner C. Trends in biomass fractionation in wheat and barley from wild ancestors to modern cultivars. Plant Biol. 2002;4(2):258–65.

Burnett AC. Source–sink relationships. In: eLS. Edited by Sons JW. 2021:1–12.

White AC, Rogers A, Rees M, Osborne CP. How can we make plants grow faster? A source–sink perspective on growth rate. J Exp Bot. 2015;67(1):31–45.

Yuan S, Li Y, Peng S. Leaf lateral asymmetry in morphological and physiological traits of rice plant. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129832.

Gladun LV, Karpov EA. Distribution of assimilates from the flag leaf of rice during the reproductive period of development. Russ J Plant Physiol. 1993;40(2):215–8.

Pask A, Pietragalla J, Mullan D, Reynolds M. Physiological breeding II: a field guide to wheat phenotyping. Cimmyt. 2012.

Briggs KG, Aytenfisu A. Relationships between morphological characters above the flag leaf node and grain yield in spring wheats. Crop Sci. 1980;20(3):350–4.

Chitwood Daniel H, Sinha Neelima R. Evolutionary and Environmental Forces Sculpting Leaf Development. Curr Biol. 2016;26(7):R297–306.

Mark Westoby, Daniel S. Falster, Angela T. Moles, Peter A. Vesk a, Wright IJ: Plant Ecological Strategies: Some Leading Dimensions of Variation Between Species. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 2002, 33(1):125-159.

Murata Y. Studies on the photosynthesis of rice plants and its culture significance. Bull Natl Inst Agr Sci. 1961:D-9:1-169.

Cook MG, Evans LT. Some physiological aspects of the domestication and improvement of rice (Oryza spp.). Field Crops Res. 1983;6:219–38.

Marenco RA, Antezana-Vera SA, Nascimento HCS. Relationship between specific leaf area, leaf thickness, leaf water content and SPAD-502 readings in six Amazonian tree species. Photosynthetica. 2009;47(2):184–90.

Xia Z. Studies on inheritance and selection of the leaf shape in Keng rice. Zuo Wu Xue Bao. 1983;4:275-82.

Tsunoda S. A developmental analysis of yielding ability in varieties of field crops : IV. Quantrtatrve and spatral development of the stem-system. JPN J BREED. 1962;12(1):49–56.

Liu CG, Zhou XQ, Chen DG, Li LJ, Li JC, Chen YD. Natural variation of leaf thickness and its association to yield traits in indica rice. J Integr Agric. 2014;13(2):316–25.

Blanco FF, Folegatti MV. Estimation of leaf area for greenhouse cucumber by linear measurements under salinity and grafting. Sci Agric. 2005;62(4):305–9.

Peksen E. Non-destructive leaf area estimation model for faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Sci Hortic. 2007;113(4):322–8.

Mohiuddin SH, Croy LI. Flag leaf and peduncle area duration in relation to winter wheat grain yield. J Agron. 1980;72(2):299–301.

Simón MR. Inheritance of flag-leaf angle, flag-leaf area and flag-leaf area duration in four wheat crosses. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98(2):310–4.

Fowler CW, Rasmusson DC: Leaf area relationships and in heritance in barley. Crop Sci 1969, 9(6):cropsci1969.0011183X000900060016x.

Jia H, Wan H, Yang S, Zhang Z, Kong Z, Xue S, et al. Genetic dissection of yield-related traits in a recombinant inbred line population created using a key breeding parent in China’s wheat breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126(8):2123–39.

Wu Q, Chen Y, Fu L, Zhou S, Chen J, Zhao X, et al. QTL mapping of flag leaf traits in common wheat using an integrated high-density SSR and SNP genetic linkage map. Euphytica. 2016;208(2):337–51.

Bezant J, Laurie D, Pratchett N, Chojecki J, Kearsey M. Mapping QTL controlling yield and yield components in a spring barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cross using marker regression. Mol Breed. 1997;3(1):29–38.

Wang Q, Sun G, Ren X, Du B, Cheng Y, Wang Y, et al. Dissecting the genetic basis of grain size and weight in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) by QTL and comparative genetic analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:469.

Khahani B, Tavakol E, Shariati JV. Genome-wide meta-analysis on yield and yield-related QTLs in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Mol Breed. 2019;39(4):56.

Ogrodowicz P, Adamski T, Mikołajczak K, Kuczyńska A, Surma M, Krajewski P, et al. QTLs for earliness and yield-forming traits in the Lubuski × CamB barley RIL population under various water regimes. J Appl Genet. 2017;58(1):49–65.

Vafadar Shamasbi F, Jamali SH, Sadeghzadeh B, Abdollahi Mandoulakani B. Genetic mapping of quantitative trait loci for yield-affecting traits in a barley doubled haploid population derived from Clipper × Sahara 3771. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:688.

Watt C, Zhou G, McFawn L-A, Chalmers KJ, Li C. Fine mapping of qGL5H, a major grain length locus in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132(4):883–93.

Watt C, Zhou G, McFawn L-A, Li C. Fine mapping qGL2H, a major locus controlling grain length in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133(7):2095–103.

Wang J, Wu X, Yue W, Zhao C, Yang J, Zhou M. Identification of QTL for barley grain size. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11287.

Du B, Liu L, Wang Q, Sun G, Ren X, Li C, et al. Identification of QTL underlying the leaf length and area of different leaves in barley. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4431.

Shaaf S, Bretani G, Biswas A, Fontana IM, Rossini L. Genetics of barley tiller and leaf development. J Integr Plant Biol. 2019;61(3):226–56.

Jabbari M, Fakheri BA, Aghnoum R, Mahdi Nezhad N, Ataei R. GWAS analysis in spring barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) for morphological traits exposed to drought. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204952.

Xue D-w, Chen M, Zhou M, Chen S, Mao Y, Zhang G. QTL analysis of flag leaf in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) for morphological traits and chlorophyll content. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008;9(12):938–43.

Teng S, Qian Q, Zeng D, Kunihiro Y, Fujimoto K, Huang D, et al. QTL analysis of leaf photosynthetic rate and related physiological traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica. 2004;135(1):1–7.

Adachi S, Nito N, Kondo M, Yamamoto T, Arai-Sanoh Y, Ando T, et al. Identification of chromosomal regions controlling the leaf photosynthetic rate in rice by using a progeny from japonica and high-yielding indica varieties. Plant Prod Sci. 2011;14(2):118–27.

Gu J, Yin X, Struik PC, Stomph TJ, Wang H. Using chromosome introgression lines to map quantitative trait loci for photosynthesis parameters in rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaves under drought and well-watered field conditions. J Exp Bot. 2011;63(1):455–69.

Takai T, Adachi S, Taguchi-Shiobara F, Sanoh-Arai Y, Iwasawa N, Yoshinaga S, et al. A natural variant of NAL1, selected in high-yield rice breeding programs, pleiotropically increases photosynthesis rate. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):2149.

Adachi S, Yoshikawa K, Yamanouchi U, Tanabata T, Sun J, Ookawa T, et al. Fine mapping of carbon assimilation Rate 8, a quantitative trait locus for flag leaf nitrogen content, stomatal conductance and photosynthesis in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:60.

Hussain W, Baenziger PS, Belamkar V, Guttieri MJ, Venegas JP, Easterly A, et al. Genotyping-by-sequencing derived high-density linkage map and its application to QTL mapping of flag leaf traits in bread wheat. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–15.

Huang S, Sun L, Hu X, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Nevo E, et al. Associations of canopy leaf traits with SNP markers in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. durum (Desf.)). PloS One. 2018;13(10):e0206226.

Liu K, Xu H, Liu G, Guan P, Zhou X, Peng H, et al. QTL mapping of flag leaf-related traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2018;131(4):839–49.

Zhao C, Bao Y, Wang X, Yu H, Ding A, Guan C, et al. QTL for flag leaf size and their influence on yield-related traits in wheat. Euphytica. 2018;214(11):209.

Xue S, Xu F, Li G, Zhou Y, Lin M, Gao Z, et al. Fine mapping TaFLW1, a major QTL controlling flag leaf width in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126(8):1941–9.

Razzaq A, Wani SH, Saleem F, Yu M, Zhou M, Shabala S. Rewilding crops for climate resilience: economic analysis and de novo domestication strategies. J Exp Bot. 2021;72(18):6123–39.

Zheng Z, Hu H, Gao S, Zhou H, Luo W, Kage U, et al. Leaf thickness of barley: genetic dissection, candidate genes prediction and its relationship with yield-related traits. Theoretical Appl Genet. 2022;135(6):1843-54.

Xu Y, Jia Q, Zhou G, Zhang X, Angessa T, Broughton S, et al. Characterization of the sdw1 semi-dwarf gene in barley. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:11.

John GP, Scoffoni C, Sack L. Allometry of cells and tissues within leaves. Am J Bot. 2013;100(10):1936–48.

Tsuge T, Tsukaya H, Uchimiya H. Two independent and polarized processes of cell elongation regulate leaf blade expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Development. 1996;122(5):1589–600.

Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tholen D, Niinemets Ü. Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2010;155(1):108–16.

Coneva V, Chitwood DH. Genetic and developmental basis for increased leaf thickness in the Arabidopsis Cvi ecotype. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:322.

Lee YK, Kim G-T, Kim I-J, Park J, Kwak S-S, Choi G, Chung W-I: LONGIFOLIA1 and LONGIFOLIA2, two homologous genes,regulate longitudinal cell elongation in Arabidopsis. Development 2006, 133(21):4305-4314.

Mitsuda N, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Ohme-Takagi M. The NAC transcription factors NST1 and NST2 of Arabidopsis regulate secondary wall thickenings and are required for anther dehiscence. Plant Cell. 2005;17(11):2993–3006.

Wang H, Zhao Q, Chen F, Wang M, Dixon RA. NAC domain function and transcriptional control of a secondary cell wall master switch. Plant J. 2011;68(6):1104–14.

Lee JJ, Woodward AW, Chen ZJ. Gene expression changes and early events in cotton fibre development. Ann Bot. 2007;100(7):1391–401.

Turuspekov Y, Abugalieva S, Ermekbayev K, Sato K: Genetic characterization of wild barley populations (<i>Hordeum vulgare</i> ssp. <i>spontaneum</i>) from Kazakhstan based on genome wide SNP analysis. Breed Sci 2014, 64(4):399-403.

Volis S, Mendlinger S, Turuspekov Y, Esnazarov U, Abugalieva S, Orlovsky N. Allozyme variation in turkmenian populations of wild barley. Hordeum spontaneum Koch. Ann Bot. 2001;87(4):435–46.

Hu H, Ahmed I, Choudhury S, Fan Y, Shabala S, Zhang G, et al. Wild barley shows a wider diversity in genes regulating heading date compared with cultivated barley. Euphytica. 2019;215(4):75.

Zhang XC, Fan Y, Shabala S, Koutoulis A, Shabala L, Johnson P, et al. A new major-effect QTL for waterlogging tolerance in wild barley (H-spontaneum). Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130(8):1559–68.

Hu H, Choudhury S, Shabala S, Gupta S, Zhou M. Genomic regions on chromosome 5H containing a novel QTL conferring barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV (BYDV-PAV) tolerance in barley. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):11298.

Liu K, Harrison MT, Ibrahim A, Manik SMN, Johnson P, Tian X, et al. Genetic factors increasing barley grain yields under soil waterlogging. Food Energy Secur. 2020;9(4):e238.

Wright IJ, Westoby M. Differences in seedling growth behaviour among species: trait correlations across species, and trait shifts along nutrient compared to rainfall gradients. J Ecol. 1999;87(1):85–97.

Lambers H, Poorter H. Inherent Variation in Growth Rate Between Higher Plants: A Search for Physiological Causes and Ecological Consequences. In: Begon M, Fitter AH, editors. Advances in Ecological Research, vol. 23: Academic Press; 1992. p. 187–261.

Niinemets Ü. Research review. Components of leaf dry mass per area – thickness and density – alter leaf photosynthetic capacity in reverse directions in woody plants. New Phytologist. 1999;144(1):35–47.

Witkowski ETF, Lamont BB. Leaf specific mass confounds leaf density and thickness. Oecologia. 1991;88(4):486–93.

Cunningham SA, Summerhayes B, Westoby M. Evolutionary divergences in leaf structure and chemistry, comparing rainfall and soil nutrient gradients. Ecological Monographs. 1999;69(4):569–88.

Coley PD. Effects of plant growth rate and leaf lifetime on the amount and type of anti-herbivore defense. Oecologia. 1988;74(4):531–6.

Wang W, Mauleon R, Hu Z, Chebotarov D, Tai S, Wu Z, et al. Genomic variation in 3,010 diverse accessions of Asian cultivated rice. Nature. 2018;557(7703):43–9.

Zhao Q, Feng Q, Lu H, Li Y, Wang A, Tian Q, et al. Pan-genome analysis highlights the extent of genomic variation in cultivated and wild rice. Nat Genet. 2018;50(2):278–84.

Walkowiak S, Gao L, Monat C, Haberer G, Kassa MT, Brinton J, et al. Multiple wheat genomes reveal global variation in modern breeding. Nature. 2020;588(7837):277–83.

Jayakodi M, Padmarasu S, Haberer G, Bonthala VS, Gundlach H, Monat C, et al. The barley pan-genome reveals the hidden legacy of mutation breeding. Nature. 2020;588(7837):284–9.

Liu Y, Du H, Li P, Shen Y, Peng H, Liu S, et al. Pan-genome of wild and cultivated soybeans. Cell. 2020;182(1):162–176.e113.

Hirsch CN, Foerster JM, Johnson JM, Sekhon RS, Muttoni G, Vaillancourt B, et al. Insights into the maize pan-genome and pan-transcriptome. Plant Cell. 2014;26(1):121–35.

Nowicka A, Sahu PP, Kovacik M, Weigt D, Tokarz B, Krugman T, et al. Endopolyploidy variation in wild barley seeds across environmental gradients in israel. Genes. 2021;12(5):711.

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):48.

Mascher M, Gundlach H, Himmelbach A, Beier S, Twardziok SO, Wicker T, et al. A chromosome conformation capture ordered sequence of the barley genome. Nature. 2017;544(7651):427–33.

Mascher M, Wicker T, Jenkins J, Plott C, Lux T, Koh CS, Ens J, Gundlach H, Boston LB, Tulpová Z, et al. Long-read sequence assembly: a technical evaluation in barley. Plant Cell. 2021;33(6):1888–906.

Van Ooijen J. MapQTL® 6, Software for the mapping of quantitative trait loci in experimental populations of diploid species, vol. 64. Kyazma BV, Wageningen, Netherlands; 2009.

Fan Y, Shabala S, Ma Y, Xu R, Zhou M. Using QTL mapping to investigate the relationships between abiotic stress tolerance (drought and salinity) and agronomic and physiological traits. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):43.

Voorrips RE. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J Heredity. 2002;93(1):77–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project is funded by the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) of Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YN and TC collected data, conducted analyses, and wrote original draft; ZZ, CZ, CL and MZ revised the manuscript; JJ, MZ conceived and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The collection of plant material complies with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest to this work, including (but are not limited to) political, personal, religious, ideological, academic, and intellectual competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, Y., Chen, T., Zheng, Z. et al. A new major QTL for flag leaf thickness in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Plant Biol 22, 305 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03694-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03694-7