Abstract

Background

Plant breeding has been proposed as one of the most effective and environmentally safe methods to control fungal infection and to reduce fumonisin accumulation. However, conventional breeding can be hampered by the complex genetic architecture of resistance to fumonisin accumulation and marker-assisted selection is proposed as an efficient alternative. In the current study, GWAS has been performed for the first time for detecting high-resolution QTL for resistance to fumonisin accumulation in maize kernels complementing published GWAS results for Fusarium ear rot.

Results

Thirty-nine SNPs significantly associated with resistance to fumonisin accumulation in maize kernels were found and clustered into 17 QTL. Novel QTLs for fumonisin content would be at bins 3.02, 5.02, 7.05 and 8.07. Genes with annotated functions probably implicated in resistance to pathogens based on previous studies have been highlighted.

Conclusions

Breeding approaches to fix favorable functional variants for genes implicated in maize immune response signaling may be especially useful to reduce kernel contamination with fumonisins without significantly interfering in mycelia development and growth and, consequently, in the beneficial endophytic behavior of Fusarium verticillioides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maize kernels can be contaminated with many mycotoxins produced by different fungi species, most species belonging to the genera Aspergillus, Penicillium or Fusarium. Concern about kernel contamination with fumonisins is world-wide spread because these toxins are biosynthesized by species of the Gibberella fujikuroi complex, such as Fusarium proliferatum (Matsushima), F. subglutinans (Wollenw. & Reinking) and F. verticillioides (Sacc.) Nirenberg, which infect maize kernels all around the world [1]. Fumonisins have proven toxicity on animals and have been classified as possibly carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [2]. The search for strategies to reduce maize kernel contamination with fumonisins became a priority in many places of the world just few years after fumonisins were discovered [3], and plant breeding has been proposed as one of the most effective and environmentally safe methods to control fungal infection and to reduce fumonisin accumulation [4, 5]. However, conventional breeding can be hampered by the complex genetic architecture of resistance to fumonisin accumulation that appears to be controlled by many quantitative trait loci (QTL) of small effect [1]. In an attempt to avoid this problem, authors have tried to find markers linked to genes involved in resistance to Fusarium ear rot (FER) and/or fumonisin contamination to use them in marker-assisted selection programs [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Many studies were focused on detecting QTL for resistance to FER; QTL were identified in all chromosomes, except in chromosome 9. However, there are only two studies in which QTL for resistance to fumonisin contamination in maize kernels were located along with QTL for FER; authors pointed out that many QTL detected were associated with both disease traits [8, 13]. As, in addition, genotypic correlation coefficients reported between fumonisin accumulation and FER were high, ranging from 0.87 to 0.99, selection for resistance to FER has been proposed as a simpler method to reduce indirectly kernel contamination with fumonisins [14,15,16,17]. However, Eller and coauthors [18] performed selection for resistance to FER and concluded that selection for reduced FER could have limited effectiveness to improve resistance to fumonisin accumulation. In view of these results, more QTL studies to detect specific genomic regions involved in resistance to maize contamination with fumonisins are needed.

QTL mapping using linkage mapping in biparental progenies is a powerful tool to uncover genomic regions involved in the inheritance of a particular trait, but the QTL resolution is low. Therefore, as the lack of tight linkage between markers and QTL could compromise the usefulness of marker-assisted selection (MAS), fine mapping of detected QTL is often addressed before conducting MAS. Fine mapping allows breeders to significantly reduce the confidence interval for QTL position and, at the end, to locate the gene or genes behind the QTL; but it is expensive and time-consuming. In this context, genome-wide association study (GWAS) using inbred line panels appears as an effective alternative to this step-by-step approach for detection of genes involved in resistance to maize kernel contamination with fumonisin. GWAS has been extensively used for detecting associations between molecular markers and resistance to FER or to seedling infection [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Novel maize loci significantly associated with improved resistance to FER were identified, each locus explaining a small proportion of phenotypic variability. As the alleles conferring greater disease resistance were rare and present in higher frequencies in tropical maize, GWAS has been proposed as a useful tool for identifying specific FER resistance allele variants in tropical maize germplasm to introgress them into temperate dent germplasm [19, 20]. In the current study, GWAS has been performed for the first time for detecting high-resolution QTL for resistance to fumonisin accumulation in maize kernels.

Candidate genes for maize resistance to FER have been proposed in transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome studies deployed to study maize response to infection by Fusarium verticillioides in genotypes with contrasting levels of resistance to FER [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Genes with differential transcript accumulation between resistant and susceptible inbreds at control conditions as well as those specifically induced or downregulated in resistant genotypes after inoculation can be considered as valuable resources to uncover maize resistance mechanisms to FER, especially when they are located in genomic regions containing QTLs. In the present study, this complete information has been taken into account in order to propose candidate genes for the high-resolution QTL detected for fumonisin contamination.

Results

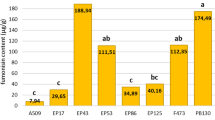

Genetic heritability for fumonisin content in the kernels (0.42 ± 0.08), estimated on an entry mean basis, was low but significantly different from zero. Genotype x environment interaction was also highly important for this trait (Table 1), but the phenotypic mean across environments would finely correspond to genotype performance because genotype x environment significant effects have been rather attributed to heterogeneity of genotypic variances than to the lack of correlation of genotype performance in different environments [14, 36]. Dispersion of data was higher in 2011 than in 2010 (Additional file 1: Figure S1), but Spearman correlation coefficients between the averaged fumonisin contents and those determined in 2010 and 2011 experiments were 0.834 and 0.830, respectively. BLUE values of inbreds CML158Q, Pa875, CML218, CML228, Mo18W, GT112 and HP301 (belonging to different germplasm groups [37]) were in both years below 10.

The phenotypic correlation between fumonisin content and FER was not significant (0.40 ± 0.32), meanwhile the genotypic correlation between both traits was higher and significant (0.88 ± 0.11). However, no co-localizations of QTLs for fumonisin content and FER were observed (Data not shown). Phenotypic (− 0.18 ± 0.05) and genotypic (− 0.41 ± 0.11) correlation coefficients between fumonisin content and days to silking were negative and significant.

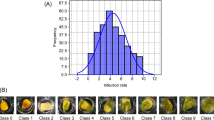

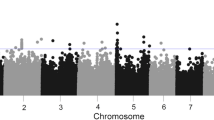

The 256 inbreds were clustered into 11 groups using the optimum compression option in TASSEL, and the background genetic effects, modeled by the kinship matrix, accounted for the 29% of phenotypic variation for fumonisin content. The “goodness of fit” of the MLM used is shown in the Fig. 1; the outliers, as expected, were situated on the upper part of the Q-Q plot and were scattered across all chromosomes (Figs. 1 and 2). However, only thirty-nine of those outliers surpassed the RMIP threshold of 0.5 and could be considered as reliably associated with fumonisin accumulation in the kernels (Table 2). Significant SNPs were grouped into a unique QTL when they were located in a genomic region in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.4), resulting in 17 QTLs for fumonisin accumulation (Table 2). Significant SNPs for resistance to fumonisin accumulation in maize kernels were found in bins 1.07, 1.09, 2.08, 3.02, 3.04, 3.05, 3.06, 3.08, 3.09, 4.02, 4.05, 5.02, 6.07, 7.05, 8.07, 9.03. In general, no LD (r2 > 0.4) was found among SNPs associated with different QTLs, except between SNPs in QTLs at chromosomes 3 and 4 (Fig. 3).

The supporting intervals for the QTL ranged from thousands to millions of bp and were positioned in the B73 genome v2 (RefGen_v2) (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-7/fasta/zea_mays/dna/) as well as in the B73 genome v4 (RefGen_v4) [38] (Table 2 and Additional file 2: Table S1). All genes located within the supporting interval (based on RefGen_v4) of each QTL were considered as candidate genes for that QTL (Additional file 2: Table S1), and genes with annotated functions probably implicated in resistance to pathogens based on previous studies will be discussed. No candidate genes, except the SNP-containing genes, are proposed for QTL located in genomic regions where linkage disequilibrium is high and confidence interval spans more than 2 Mbp, such as those in bins 4.05 and 9.03.

Discussion

Differences among inbreds for fumonisin content in the kernels were significant and the genetic heritability for fumonisin content in the kernels was low but significantly different from zero showing that there is additive genetic variability among inbreds for resistance to fumonisin accumulation. The heritability for fumonisin content was similar to those reported by Hung and Holland [39], but smaller than those observed in genetically narrower populations [14,15,16]. Low heritability for fumonisin contamination stresses the importance of implementing marker-assisted selection methods based on stable QTLs in order to increase maize resistance to kernel contamination. In this scenario, marker-assisted selection would be even more efficient than arduous and expensive selection programs based on the phenotype.

The lack of significant phenotypic correlation between fumonisin content and FER could be due to low pathogenicity of the isolate or/and climatic conditions that would not be favorable for disease spread since, in the same experiments, reported FER values for the same inbreds were moderate [19], while those conditions would be more favorable for fumonisin accumulation because the average mean for kernel contamination was 58.4 ppm [one third of inbreds presented mean values above 50 ppm, meanwhile approximately 10% of inbreds presented values below 10 ppm]. Then, conducive conditions for fumonisin accumulation but not for disease development could account for the lack of phenotypic correlation between both traits, contrarily to reported results [1], and no detection of QTL for FER [19] using the same experimental trials.

In previous studies, positive correlation coefficients between days to silking and fumonisin accumulation were found [13, 14]; meanwhile, in the current study, the genotypic correlation coefficient between fumonisin content and days to silking was negative. However, co-localization of QTLs for fumonisin content (Table 2) and days to silking (data not shown) occurred in the interval 5,405,928-5,466,378 of chromosome 4 and alleles for increased fumonisin content and days to silking appeared to be linked in coupling phase. We hypothesize that population structure could be responsible for the significant and positive genotypic correlation coefficient observed between both traits in the current study because tropical maize inbreds are later and show higher frequencies for resistance alleles to FER [20]. Therefore, after removing random genetic variation (variation explained by additive relationship matrix), linked genetic variants for increased accumulation of fumonisin and delayed maturity can be found.

The 39 SNPs significantly associated with fumonisin accumulation in the maize kernels were grouped in 17 high-resolution QTLs and, at least, four of them would be behind novel QTL not reported in previous studies [8, 13]. These novel QTLs for fumonisin content would be at bins 3.02, 5.02, 7.05 and 8.07. Genomic regions significantly associated with FER in previous GWAS did not overlap, in general with QTL supporting intervals for kernel contamination with fumonisins, excepting particular regions in bins 3.08, 4.05, 7.05, and 9.03 [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Therefore, These QTL could be especially useful to reduce kernel contamination with fumonisins without significantly interfering in mycelia development and growth and, consequently, in the known beneficial endophytic behavior of Fusarium verticillioides. Fusarium verticillioides has already been proved as contributor to host fitness through growth promotion and induction of defense-associated changes such as lignin deposition in the cell wall at seedling stage and growth increased in mature plants [40,41,42,43]. However, due to the polygenic nature of genetics for maize fumonisin contamination, breeding should rather be based on genomic selection (GS) models than on marker-assisted approaches focused on fixing exclusively favorable genetic variants for the QTL detected. However, precisely mapped QTL could improve genomic prediction accuracy using stepwise linear regression mixed model to unify GWAS and GS in a single statistical model [44].

Candidate genes

QTL supporting interval comprises the QTL-surrounding region in LD (r2 > 0.4). All genes contained in the supporting interval were considered as candidate genes and identified and characterized by the use of the MaizeGDB genome browser. However, discussion will be mainly focused on genes with annotated functions probably implicated in resistance to pathogens.

Toxin biosynthesis seems to be coupled to colonization of the host and some Fusarium verticillioides genes with important roles in both processes have been characterized [40, 45, 46]. For example, the gene FUG1 plays a role in mitigating stresses associated with the host environment, being a critical component of the genetic regulatory network underlying maize kernel pathogenesis and fumonisin biosynthesis. Accordingly, it is expected that some host genes involved in defense against fungal disease would be also implicated in toxin modulation.

Plants have an innate immunity system to defend themselves against pathogens [47]. Pattern triggered immunity (PTI) or basal defense response is mediated by plant pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), but plant pathogens can suppress this basal defense response by effectors which contribute to pathogen virulence. However, a secondary immune response, effector-triggered immunity (ETI) mediated by resistance proteins (RPs) that recognize effector-induced perturbations of host targets, allows plants to stop pathogen growth. In addition, during induction of local immune responses, systemic acquired resistance (SAR) can become activated. PTI seems to play a primary role in the resistance of maize to Fusarium verticillioides, and maize resistance would be achieved somehow through PTI-induced acquired systemic immunity where ABA, SA, and JA hormone signaling pathways can be involved [33]. Therefore, genes directly implicated in the immune plant response deserve special attention as preferred candidate genes for the significant associations found.

Zm00001d042659 (at ≈ 175 Mbp in chromosome 3 of the RefGenB73_v4) has been annotated as a protein SRC2-like protein gene and, consequently, could be implicated in recognition of PAMPs because, in pepper, a SRC2 protein acts as a required interacting partner of a fungal elicitor of the immune response [48]. L-type lectin-domain containing receptor kinases have been proposed as plant sensors of pathogen invasion and, consequently, the gene Zm00001d043781, annotated as an L-type lectin-domain containing receptor kinase IV.1 gene, could be a good candidate gene for the QTL at 3.08 [49].

The largest class of resistance proteins involved in ETI response consists of nucleotide-binding-leucine rich repeat (NB-LRR) proteins. In Arabidopsis, the gene LOV1 encodes a typical NB-LRR but this protein is unique because it confers sensitivity to the fungal toxin victorin and susceptibility to the fungus Cochliobolus victoriae. In the current study, a putative inactive disease susceptibility protein LOV1 (Zm00001d032376) gene is located within the confidence interval of QTL at 1.07 and is proposed as probable candidate gene for that QTL.

Similarly, genes involved in plant immune response signaling could contribute to plant resistance. Salicylic acid is a defense hormone required for both local and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in plants. Salycilic acid is synthesized from chorismate, the end product of the shikimate pathway, although the complete biosynthetic route has yet to be established. Then, genes involved in chorismate biosynthesis and in the response to pathogen effector proteins, such as phospho-2-dehydro-3-deoxyheptonate aldolase genes, are good candidate genes for the QTL detected [50, 51]. Gene Zm00001d013611 has been proposed as a phospho-2-dehydro-3-deoxyheptonate aldolase 2, chloroplastic-like gene and could be behind the QTL at 5.02. Besides structural genes of the chorismate pathway, genes with proven regulatory role can be highlighted as candidate genes. Zm00001d032368 which codifies for Protein SAR DEFICIENT 1 (SARD1) is a good candidate for the QTL found in 1.07 because SARD1 has been reported as a positive regulator required for salicylic acid accumulation [52]. The gene Zm00001d033389 is proposed as the preferred candidate gene for QTL at 1.09 (contained in the confidence interval of the QTL that spans from 261,226,685 to 261,380,422 in RefGen_v4) because codifies for a VQ motif family protein. Members of the VQ family play either positive or negative roles in SA- and/or JA-mediated plant immune responses [53].

As auxin can interfere with plant defense circuitry through antagonism with SA signaling [54], another set of interesting genes for future validations comprised genes with proven or probable functions in auxin signaling [Zm00001d039513 (Aux/IAA-transcription factor 7 at bin 3.02), Zm00001d044172 (srph1 - SGT1 disease resistance homolog1at bin 3.09), and Zm00001d022400 (F-box protein SKIP5 gene at bin 7.05)] [55] and auxin signal transduction [Zm00001d048841 (probable patatin-like phospholipase gene at bin 4.02)] [56]. The possible effect of genes modulating auxin signaling and transport on maize seedling resistance to Gibberella stalk rot caused by Fusarium graminearum has already been shown [57]. In general, modulation of plant disease resistance by auxin and/or its signaling pathway has been proposed based on results from many pathogen-host interactions [54]. Finally, it has also been shown that canonical cell cycle regulators such as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors form part of signaling pathway directly involved in ETI and could also contribute to basal resistance [58]. Therefore, Zm00001d048837 and Zm00001d013610 annotated as likely cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors could be stressed as candidate genes for QTL at 4.02 and 5.02, respectively, and deserve especial attention.

In addition to salicylic acid, plant lipid metabolites are important signal molecules in local and systemic defense against pathogens [59]. More specifically, fungal and plant oxylipins (including the well-known jasmonic acid), produced via the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, have a primordial role as signals in plant–pathogen ecosystems [60]. Fungal oxylipins attempt to reprogram PTI and, in turn, the host counteracts by producing its own oxylipins to impede pathogen infection: However, fungal oxylipins can also induce Effector Triggered Susceptibility (ETS) by activating genes of the host oxylipin pathway, such as ZmLOX3, that suppress defense-related branches of the maize oxylipin pathway and favor Fusarium verticillioides virulence and fumonisin accumulation [60, 61]. Sphingolipids, also play an important role in the regulation of the delicate arm race between the microbe and the host in mammals. A similar involvement of sphingolipids in immune plant response signaling could be hypothesized based on scarce studies that identify genes implicated in sphingolipid metabolism as important factors in resistance to fungal infection [62, 63]. Under field conditions, it has been stablished that oxilipin and sphingolipid metabolism in maize kernels interferes with Fusarium verticillioides growth and fumonisin production; early activation of plant lipoxygenase genes and genes for jasmonic acid biosynthesis appear important factors for conferring resistance [35, 64, 65]. Therefore, Zm00001d039768 (Acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 4 peroxisomal gene) is proposed for the QTL at 3.04 which contains significant SNPs S3_15,056,252, S3_15,057,326, S3_15,057,331, and S3_15,057,578; and Zm00001d044175 (Neutral/alkaline non-lysosomal ceramidase gene) is proposed for the QTL at 3.09.

Finally, another lipid component of the plant, the cuticle, could also play an important role in plant defense against attack by fungi. The plant cuticle is a protective sheathing produced by epidermal cells of aerial plant organs that provides the first barrier that fungi must overcome in order to get into the plant tissue. However, the cuticle also provides chemical and physical cues that are necessary for the development of essential infection structures for many fungal pathogens and perception of cuticle alterations by fungi could be essential for promoting plant defenses [66]. In rice, an abnormal cuticle formation may affect the signaling of plant defense against the hemibiotrophic fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae [67]. Therefore, the gene myb28 (Zm00001d050400) which is orthologous to the Atmyb16 gene that participates in the regulation of cuticle biosynthesis in Arabidopsis [68] could be a good candidate for the QTL at 4.05.

There are numerous pathogenesis-related changes that follow PAMP perception, such as rapid in fluxes of cytosolic Ca+2and production/accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Genes involved in protection of plant tissues against oxidative damage and ROS detoxification could be important in maize defense against Fusarium verticillioides; the constitutive higher antioxidant content in resistant genotypes seeming crucial in maize kernels in preparation of pathogen attack [34]. Therefore, genes involved in ROS production and ROS-scavenging and ROS-detoxification could be also good candidates: Zm00001d042061 (a probable NADPH: quinone oxodoreductase gene) was suggested as candidate gene for the QTL at 3.05; Zm00001d042555 (a putative alcohol dehydrogenase gene) for the QTL at ≈ 171 Mbp in chromosome 3 of the RefGenB73_v4 (bin 3.06); Zm00001d043787, Zm00001d043789, and Zm00001d043795 (glutathione transferase genes) and Zm00001d043782 [ZmRav1, that might improve stress tolerance through the regulation of the expression of genes involved in ROS scavenging [69]] for the QTL at 3.08; and the gene Zm00001d046455 (a gene codifying for a protein with predicted oxidoreductase and transferase activities) for the QTL at 9.03.

Lanubille and coauthors observed that the response of a resistant genotype to kernel infection by Fusarium verticillioides was characterized by a constitutive expression, and by a prompt and enhanced induction of some key genes [30]. Therefore, candidate genes in the current GWAS, that were differentially transcribed at control conditions in resistant and susceptible genotypes as well as those specifically modified by Fusarium verticillioides infection in the resistant genotype in the work by Lanubile et al. [30] (Zm00001d007025, Zm00001d007032 and Zm00001d043798), would deserve especial attention. The functions of genes Zm00001d007025 and Zm00001d007032 (named previously GRMZM2G422537 and GRMZM2G035356, respectively) are unknown; while Zm00001d043798 (named before GRMZM2G448710), a Leaf rust 10 disease-resistance locus receptor-like protein kinase gene, could be involved in basal defense against fungi [70].

Conclusions

Complexity of genetics of maize resistance to kernel contamination with fumonisins has been confirmed because genotype x environment interaction had an important contribution to phenotypic variation and many genes with small effects would contribute to genetic variation. Thirty-nine SNPs significantly associated with resistance to fumonisin accumulation in maize kernels were found and clustered into 17 QTL. Novel QTLs for fumonisin content would be at bins 3.02, 5.02, 7.05 and 8.07. The high resolution of QTLs found using GWAS allows us to propose candidate genes for these QTLs; many candidates being implicated in maize immune response signaling. Functional variation for those genes may be especially useful to reduce kernel contamination with fumonisins without significantly interfering in mycelia development and growth and, consequently, in the beneficial endophytic behavior of Fusarium verticillioides. Validations of the contributions of these candidate genes to resistance to fuminisin accumulation in maize kernels will be the focus of future works.

Methods

Plant material and field experiments

A subset of 270 inbred lines from a maize diversity panel (composed of 302 inbred lines) that represents much of the diversity available in public breeding sector around the world [71] was evaluated in 2010 and 2011 under inoculation with Fusarium verticillioides. Seeds were provided by the North Central Regional Plant Introduction Station (NCRPIS) in Ames, Iowa, and NCRPIS accession names are shown in Additional file 3 Table S2.

Evaluations were done at Pontevedra (42°24′ N, 8°38′ W, and 20 m above sea level), Spain, using an 18 × 15 α-lattice design with two replications. Trials were hand-planted and each experimental plot consisted of one row spaced 0.8 m apart from the other row with 29 two-kernel hills spaced 0.18 m apart. Plots were overplanted and thinned, obtaining a final density of ~ 70,000 plant ha− 1. In each row, between seven and 14 days after silking date, five primary ears were inoculated with two milliliters of a spore suspension of a local toxigenic isolate of Fusarium verticillioides using a tested kernel inoculation protocol [72]. The spore suspension contained 106 spores per milliliter and was injected into the center of the ear using a four-needle vaccinator. Inoculated ears from each row were collected 2 months after inoculation, dried at 35 °C for 1 week, and shelled. From each plot, a representative kernel sample of approximately 200 g was ground and stored at 4 °C until performing chemical analyses. Kernels were ground through a 0.75 mm screen in a Pulverisette 14 rotor mill (Fritsch GmbH, Oberstein, Germany).

Ground samples were sent to the Food Technology Department of the University of Lleida, Spain, for determination of total fumonisin (fumonisins B1, B2, and B3) content using a commercial ELISA kit (R-Biopharm Rhône Ltd., Glasgow, Scotland, UK). This kit is a competitive enzyme immunoassay for quantification of fumonisin residues in maize. The recovery rate of the test was approximately 60% with a mean coefficient of variation of approximately 8%; specifities for B1, B2, and B3 were 100%, around 40%, and almost 100%, respectively, and the detection limit was 0.025 ppm (mg kg− 1). Extraction and preparation of samples, as well as test performance, were carried out as described in the commercial kits.

Genotypic data

We used the genotypes of 256 inbred lines with phenotypic data in both years for a set of approximately 990,000 SNP markers (AllZeaGBSv2.7) derived from a genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) strategy (Elshire et al. 2011) and uplifted to AGPv3 (Glaubitz et al. 2014) [73]. SNPs in chromosome 0, as well as monomeric and multiallelic SNPs and insertion/deletion polymorphisms (INDELs) were excluded. Then, data set was first filtered to exclude SNPs with more than 20% missing genotype data, and minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 5%. After performing imputation with Beagle v4.0 (Browning and Browning 2016), a second filtering (missing > 20% and MAF < 5%) was done after setting heterozygous genotypes as missing in the analysis. A total of 226,446 filtered SNPs distributed across the maize genome were used for GWAS analysis. After performing a linkage disequilibrium-based pruning in software Plink v1.9 a subset of ~ 99 k SNPs was obtained and used to perform a kinship matrix (K) in Tassel 5.

Statistical analyses

Heritabilities (\( {\widehat{h}}^2 \)) across environments were estimated for fumonisin contamination on a family-mean basis as described by Holland et al. [74]. The genetic and phenotypic correlations between fumonisin content and other data previously published [75], days to silking and FER, were computed following Holland [76]. Best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE) was estimated for each inbred line using the SAS mixed model procedure (PROC MIXED) and considering inbred line as fixed effect and replication within year, block within replication*year and year as random effects. Line BLUEs were used to perform GWAS.

Genome-wide association analysis based on mixed linear model (MLM) was performed in Tassel V5.2.25 [77]. The MLM used by Tassel was

where y is the vector of phenotypes (BLUEs), β is a vector of fixed effects, including the SNP marker tested, u is a vector of random additive effects (inbred lines), X and Z represents matrices, and e is a vector of random residuals. The variance of random line effects was modeled as Var(u) = K \( {\sigma}_a^2 \), where K is the n × n matrix of pairwise kinship coefficient and \( {\sigma}_a^2 \) is the estimated additive genetic variance [78]. Restricted maximum likelihood estimates of variance components were obtained by using the optimum compression level (compressed MLM) and population parameters previously determined options (P3D) in Tassel [79].

To identify SNPs with the most robust associations with traits, a subsampling or subagging procedure was employed in GWAS analysis [80, 81]. Each of 100 subsampled datasets generated using the R software [82] comprised a random sample of 80% of inbred lines from the diversity population. Only SNP markers determined as significant at p < 1 × 10− 4 and subsequently detected in ≥50 subsamples, i.e. resample model inclusion probability (RMIP) threshold of 0.50, were considered as significantly associated with the trait under study. Analysis of linkage disequilibrium (LD) among SNPs significantly associated with fumonisin content was performed in Tassel.

Candidate gene selection

We also examined the LD in the genomic region around each significant SNP to stablish a supporting interval for the significant association. That supporting interval would comprise the surrounding region in LD (r2 > 0.4). All genes contained in the supporting interval were considered as candidate genes and identified and characterized by the use of the MaizeGDB genome browser [83]. Although SNP positions were referenced to the maize B73 RefGen_v2, the genes flanking the region in LD were positioned in the maize B73 RefGen_v4 to perform the search for candidate genes in the latest version of the B73 sequence.

Abbreviations

- FER:

-

Fusarium Ear Rot

- GS:

-

Genomic selection

- GWAS:

-

Genome-Wide Association Study

- LD:

-

Linkage Disequilibrium

- MAS:

-

Marker-Assisted Selection

- QTLs:

-

Quantitative Trait Loci

- SNP:

-

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

References

Santiago R, Cao A, Butron A. Genetic factors involved in fumonisin accumulation in maize kernels and their implications in maize agronomic management and breeding. Toxins. 2015;7(8):3267–96.

IARC: Fumonisin B1. Sometraditional herbalmedicines, somemycotoxins, naphthalene and styrene. In: 82 Monograph of the International Agency for Research of Cancer on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lyon, France; 2002: 301–306.

Munkvold GP, Desjardins AE. Fumonisins in maize - can we reduce their occurrence? Plant Dis. 1997;81(6):556–65.

Jouany JP. Methods for preventing, decontaminating and minimizing the toxicity of mycotoxins in feeds. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2007;137(3–4):342–62.

Eller MS, Holland JB, Payne GA. Breeding for improved resistance to fumonisin contamination in maize. Toxin Rev. 2008;27(3–4):371–89.

Ding J-Q, Wang X-M, Chander S, Yan J-B, Li J-S. QTL mapping of resistance to Fusarium ear rot using a RIL population in maize. Mol Breed. 2008;22(3):395–403.

Pérez-Brito D, Jeffers D, González-de-León D, Khairallah M, Cortés-Cruz M, Velázquez-Cardelas G, Azpíroz-Rivero S, Srinivasan G. QTL mapping of Fusarium moniliforme ear rot resistance in highland maize, Mexico. Agrociencia. 2001;35:181–96.

Robertson-Hoyt LA, Jines MP, Balint-Kurti PJ, Kleinschmidt CE, White DG, Payne GA, Maragos CM, Molnar TL, Holland JB. QTL mapping for fusarium ear rot and fumonisin contamination resistance in two maize populations. Crop Sci. 2006;46(4):1734–43.

Chen JF, Ding JQ, Li HM, Li ZM, Sun XD, Li JJ, Wang RX, Dai XD, Dong HF, Song WB, et al. Detection and verification of quantitative trait loci for resistance to Fusarium ear rot in maize. Mol Breed. 2012;30(4):1649–56.

Giomi GM, Kreff ED, Iglesias J, Fauguel CM, Fernandez M, Oviedo MS, Presello DA. Quantitative trait loci for Fusarium and Gibberella ear rot resistance in Argentinian maize germplasm. Euphytica. 2016;211(3):287–94.

Zhang F, Wan XQ, Pan GT. QTL mapping of Fusarium moniliforme ear rot resistance in maize. 1. Map construction with microsatellite and AFLP markers. J Appl Genetics. 2006;47(1):9–15.

Li ZM, Ding JQ, Wang RX, Chen JF, Sun XD, Chen W, Song WB, Dong HF, Dai XD, Xia ZL, et al. A new QTL for resistance to Fusarium ear rot in maize. J Appl Genetics. 2011;52(4):403–6.

Maschietto V, Colombi C, Pirona R, Pea G, Strozzi F, Marocco A, Rossini L, Lanubile A. QTL mapping and candidate genes for resistance to Fusarium ear rot and fumonisin contamination in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:20.

Robertson LA, Kleinschmidt CE, White DG, Payne GA, Maragos CM, Holland JB. Heritabilities and correlations of fusarium ear rot resistance and fumonisin contamination resistance in two maize populations. Crop Sci. 2006;46(1):353–61.

Löffler M, Kessel B, Ouzunova M, Miedaner T. Covariation between line and testcross performance for reduced mycotoxin concentrations in European maize after silk channel inoculation of two Fusarium species. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;122(5):925–34.

Bolduan C, Miedaner T, Schipprack W, Dhillon BS, Melchinger AE. Genetic variation for resistance to ear rots and mycotoxins contamination in early European maize inbred lines. Crop Sci. 2009;49(6):2019–28.

Löffler M, Miedaner T, Kessel B, Ouzunova M. Mycotoxin accumulation and corresponding ear rot rating in three maturity groups of European maize inoculated by two Fusarium species. Euphytica. 2010;174(2):153–64.

Eller MS, Payne GA, Holland JB. Selection for reduced Fusarium ear rot and fumonisin content in advanced backcross maize lines and their topcross hybrids. Crop Sci. 2010;50(6):2249–60.

Zila CT, Fernando Samayoa L, Santiago R, Butron A, Holland JB. A genome-wide association study reveals genes associated with Fusarium ear rot resistance in a maize core diversity panel. G3-Genes Genomes Genetics. 2013;3(11):2095–104.

Zila CT, Ogut F, Romay MC, Gardner CA, Buckler ES, Holland JB. Genome-wide association study of Fusarium ear rot disease in the U.S.A. maize inbred line collection. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:372.

Ju M, Zhou ZJ, Mu C, Zhang XC, Gao JY, Liang YK, Chen JF, Wu YB, Li XP, Wang SW, et al. Dissecting the genetic architecture of Fusarium verticillioides seed rot resistance in maize by combining QTL mapping and genome-wide association analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46446.

Coan MMD, Senhorinho HJC, Pinto RJB, Scapim CA, Tessmann DJ, Williams WP, Warburton ML. Genome-wide association study of resistance to ear rot by Fusarium verticillioides in a tropical field maize and popcorn core collection. Crop Sci. 2018;58(2):564–78.

Chen J, Shrestha R, Ding JQ, Zheng HJ, Mu CH, Wu JY, Mahuku G. Genome-wide association study and QTL mapping reveal genomic loci associated with Fusarium ear rot resistance in Tropical maize germplasm. G3-Genes Genomes Genetics. 2016;6(12):3803–15.

de Jong G, Pamplona AKA, Von Pinho RG, Balestre M. Genome-wide association analysis of ear rot resistance caused by Fusarium verticillioides in maize. Genomics. 2018;110(5):291–303.

Butron A, Santiago R, Cao A, Samayoa LF, Malvar RA. QTLs for resistance to Fusarium ear rot in a multi-parent advanced generation inter-cross (MAGIC) maize population. Plant Dis. 2019. (https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-09-18-1669-RE).

Stagnati L, Lanubile A, Samayoa LF, Bragalanti M, Giorni P, Busconi M, Holland JB, Marocco A. A Genome wide association study reveals markers and genes associated with tesistance to Fusarium verticillioides infection of seedlings in a maize diversity panel. G3 (Bethesda, Md). 2019;9(2):571–9.

Yuan GS, Zhang ZM, Xiang K, Shen YO, Du J, Lin HJ, Liu L, Zhao MJ, Pan GT. Different gene expressions of resistant and susceptible maize inbreds in response to Fusarium verticillioides infection. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2013;31(4):925–35.

Campos-Bermudez VA, Fauguel CM, Tronconi MA, Casati P, Presello DA, Andreo CS. Transcriptional and metabolic changes associated to the infection by Fusarium verticillioides in maize inbreds with contrasting ear rot resistance. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):10.

Lanubile A, Pasini L, Marocco A. Differential gene expression in kernels and silks of maize lines with contrasting levels of ear rot resistance after Fusarium verticillioides infection. J Plant Physiol. 2010;167(16):1398–406.

Lanubile A, Ferrarini A, Maschietto V, Delledonne M, Marocco A, Bellin D. Functional genomic analysis of constitutive and inducible defense responses to Fusarium verticillioides infection in maize genotypes with contrasting ear rot resistance. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:710.

Lanubile A, Bernardi J, Marocco A, Logrieco A, Paciolla C. Differential activation of defense genes and enzymes in maize genotypes with contrasting levels of resistance to Fusarium verticillioides. Environ Exp Bot. 2012;78:39–46.

Lanubile A, Bernardi J, Battilani P, Logrieco A, Marocco A. Resistant and susceptible maize genotypes activate different transcriptional responses against Fusarium verticillioides. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;77(1):52–9.

Wang YP, Zhou ZJ, Gao JY, Wu YB, Xia ZL, Zhang HY, Wu JY. The mechanisms of maize resistance to Fusarium verticillioides by comprehensive analysis of RNA-seq data. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1654.

Maschietto V, Lanubile A, De Leonardis S, Marocco A, Paciolla C. Constitutive expression of pathogenesis-related proteins and antioxydant enzyme activities triggers maize resistance towards Fusarium verticillioides. J Plant Physiol. 2016;200:53–61.

Maschietto V, Marocco A, Malachova A, Lanubile A. Resistance to Fusarium verticillioides and fumonisin accumulation in maize inbred lines involves an earlier and enhanced expression of lipoxygenase (LOX) genes. J Plant Physiol. 2015;188:9–18.

Butron A, Reid LM, Santiago R, Cao A, Malvar RA. Inheritance of maize resistance to gibberella and fusarium ear rots and kernel contamination with deoxynivalenol and fumonisins. Plant Pathology. 2015.

Liu KJ, Goodman M, Muse S, Smith JS, Buckler E, Doebley J. Genetic structure and diversity among maize inbred lines as inferred from DNA microsatellites. Genetics. 2003;165(4):2117–28.

Jiao Y, Peluso P, Shi J, Liang T, Stitzer MC, Wang B, Campbell MS, Stein JC, Wei X, Chin C-S, et al. Improved maize reference genome with single-molecule technologies. Nature. 2017;546(7659):524–+.

Hung H-Y, Holland JB. Diallel analysis of resistance to Fusarium ear rot and fumonisin contamination in maize. Crop Sci. 2012;52(5):2173–81.

Blacutt AA, Gold SE, Voss KA, Gao M, Glenn AE. Fusarium verticillioides: advancements in understanding the toxicity, virulence, and niche adaptations of a model mycotoxigenic pathogen of maize. Phytopathology. 2018;108(3):312–26.

Bacon CW, Glenn AE, Yates IE. Fusarium verticillioides: managing the endophytic association with maize for reduced fumonisins accumulation. Toxin Rev. 2008;27(3–4):411–46.

Yates IE, Bacon CW, Hinton DM. Effects of endophytic infection by Fusarium moniliforme on corn growth and cellular morphology. Plant Dis. 1997;81(7):723–8.

Yates IE, Widstrom NW, Bacon CW, Glenn A, Hinton DM, Sparks D, Jaworski AJ. Field performance of maize grown from Fusarium verticillioides-inoculated seed. Mycopathologia. 2005;159(1):65–73.

Li HD, Su GS, Jiang L, Bao ZM. An efficient unified model for genome-wide association studies and genomic selection. Genet Sel Evol. 2017;49:8.

Ridenour JB, Bluhm BH. The novel fungal-specific gene FUG1 has a role in pathogenicity and fumonisin biosynthesis in Fusarium verticillioides. Mol Plant Pathol. 2017;18(4):513–28.

Mukherjee M, Kim JE, Park YS, Kolomiets MV, Shim WB. Regulators of G-protein signalling in Fusarium verticillioides mediate differential host-pathogen responses on nonviable versus viable maize kernels. Mol Plant Pathol. 2011;12(5):479–91.

de Wit P. Visions & reflections (minireview) - how plants recognize pathogens and defend themselves. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64(21):2726–32.

Liu ZQ, Qiu AL, Shi LP, Cai JS, Huang XY, Yang S, Wang B, Shen L, Huang MK, Mou SL, et al. SRC2-1 is required in PcINF1-induced pepper immunity by acting as an interacting partner of PcINF1. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(13):3683–98.

Wang Y, Bouwmeester K. L-type lectin receptor kinases: New forces in plant immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(8):1164.

Winterberg B, Du Fall LA, Song XM, Pascovici D, Care N, Molloy M, Ohms S, Solomon PS. The necrotrophic effector protein SnTox3 re-programs metabolism and elicits a strong defence response in susceptible wheat leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:215.

Dempsey DMA, Vlot AC, Wildermuth MC, Klessig DF. Salicylic acid biosynthesis and metabolism. The arabidopsis book. 2011;9:e0156–6.

Zhang YX, Xu SH, Ding PT, Wang DM, Cheng YT, He J, Gao MH, Xu F, Li Y, Zhu ZH, et al. Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(42):18220–5.

Jing YJ, Lin RC. The VQ motif-containing protein family of plant-specific transcriptional regulators. Plant Physiol. 2015;169(1):371–8.

Kazan K, Manners JM. Linking development to defense: auxin in plant-pathogen interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14(7):373–82.

Mockaitis K, Estelle M. Auxin receptors and plant development: a new signaling paradigm. In: Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology vol. 2008;24:55–80.

Scherer GFE, Labusch C, Effendi Y. Phospholipases and the network of auxin signal transduction with ABP1 and TIR1 as two receptors: a comprehensive and provocative model. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:10.

Liu YJ, Guo YL, Ma CY, Zhang DF, Wang C, Yang Q, Xu ML. Transcriptome analysis of maize resistance to Fusarium graminearum. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:13.

Wang S, Gu YN, Zebell SG, Anderson LK, Wang W, Mohan R, Dong XN. A noncanonical role for the CKI-RB-E2F cell-cycle signaling pathway in plant effector-triggered immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(6):787–94.

Shah J. Lipids, lipases, and lipid-modifying enzymes in plant disease resistance. In: Annual review of phytopathology, vol. 43. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews; 2005. p. 229–60.

Battilani P, Lanubile A, Scala V, Reverberi M, Gregori R, Falavigna C, Dall'asta C, Park YS, Bennett J, Borrego EJ, et al. Oxylipins from both pathogen and host antagonize jasmonic acid-mediated defence via the 9-lipoxygenase pathway in Fusarium verticillioides infection of maize. Mol Plant Pathol. 2018;19(9):2162–76.

Scala V, Beccaccioli M, Dall'Asta C, Giorni P, Fanelli C. Analysis of the expression of genes related to oxylipin biosynthesis in Fusarium verticillioides and maize kernels during their interaction. J Plant Pathol. 2015;97(1):193–7.

Arias SL, Mary VS, Otaiza SN, Wunderlin DA, Rubinstein HR, Theumer MG. Toxin distribution and sphingoid base imbalances in Fusarium verticillioides-infected and fumonisin B1-watered maize seedlings. Phytochemistry. 2016;125:54–64.

Yu XM, Wang XJ, Huang XL, Buchenauer H, Han QM, Guo J, Zhao J, Qu ZP, Huang LL, Kang ZS. Cloning and characterization of a wheat neutral ceramidase gene ta-CDase. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(5):3447–54.

Dall'Asta C, Giorni P, Cirlini M, Reverberi M, Gregori R, Ludovici M, Camera E, Fanelli C, Battilani P, Scala V. Maize lipids play a pivotal role in the fumonisin accumulation. World Mycotoxin J. 2015;8(1):87–97.

Giorni P, Dall'Asta C, Reverberi M, Scala V, Ludovici M, Cirlini M, Galaverna G, Fanelli C, Battilani P. Open field study of some Zea mays hybrids, lipid compounds and fumonisins accumulation. Toxins. 2015;7(9):3657–70.

Raffaele S, Leger A, Roby D. Very long chain fatty acid and lipid signaling in the response of plants to pathogens. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4(2):94–9.

Garroum I, Bidzinski P, Daraspe J, Mucciolo A, Humbel BM, Morel JB, Nawrath C. Cuticular defects in Oryza sativa ATP-binding cassette transporter G31 mutant plants cause dwarfism, elevated defense responses and pathogen resistance. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57(6):1179–88.

Oshima Y, Shikata M, Koyama T, Ohtsubo N, Mitsuda N, Ohme-Takagi M. MIXTA-like transcription factors and WAX INDUCER1/SHINE1 coordinately regulate cuticle development in Arabidopsis and Torenia fournieri. Plant Cell. 2013;25(5):1609–24.

Min HW, Zheng J, Wang JH. Maize ZmRAV1 contributes to salt and osmotic stress tolerance in transgenic arabidopsis. J Plant Biol. 2014;57(1):28–42.

Marcel S, Sawers R, Oakeley E, Angliker H, Paszkowski U. Tissue-adapted invasion strategies of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant Cell. 2010;22(9):3177–87.

Flint-Garcia SA, Thuillet AC, Yu JM, Pressoir G, Romero SM, Mitchell SE, Doebley J, Kresovich S, Goodman MM, Buckler ES. Maize association population: a high-resolution platform for quantitative trait locus dissection. Plant J. 2005;44(6):1054–64.

Cao A, Butron A, Ramos AJ, Marin S, Souto C, Santiago R. Assessing white maize resistance to fumonisin contamination. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2014;138(2):283–92.

Romay MC, Millard MJ, Glaubitz JC, Peiffer J, Swarts K, Casstevens TM, Elshire RJ, Acharya C, Mitchell S, Flint-Garcia SA, et al. Comprehensive genotyping of the USA national maize inbred seed bank. Genome Biol. 2013;14(6):1–18.

Holland JB, Nyquist WE, Cervantes-Martínez CT. Estimated an interpreting heritability for plant breeding: An update. In: Janick J, editor. Plant Breeding Reviews, vol. 22. Hoboken, New Jersey: Jonh Wiley & Sons; 2003. p. 9–112.

Samayoa LF, Malvar RA, Olukolu BA, Holland JB, Butron A. Genome-wide association study reveals a set of genes associated with resistance to the Mediterranean corn borer (Sesamia nonagrioides L.) in a maize diversity panel. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:15.

Holland JB. Estimating genotypic correlations and their standard errors using multivariate restricted maximum likelihood estimation with SAS Proc MIXED. Crop Sci. 2006;46:642–56.

Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(19):2633–5.

Yu J, Pressoir G, Briggs WH, et al. A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat Genet. 2006;38(2):203–8.

Zhang Z, Ersoz E, Lai C-Q, et al. Mixed linear model approach adapted for genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2010;42(4):355–60.

Valdar W, Holmes CC, Mott R, Flint J. Mapping in structured populations by resample model averaging. Genetics. 2009;182(4):1263–77.

Panagiotou OA, Ioannidis JP. What should the genome-wide significance threshold be? Empirical replication of borderline genetic associations. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(1):273–86.

R Core Team: R: A languange and environment for statistical computing. In., 3.0.1 edn. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013.

Harper LC, Schaeffer ML, Thistle J, Gardiner J, Andorf C, Campbell D, Cannon E, Braun B, Birkett S, Lawrence C, et al. The MaizeGDB genome browser tutorial: one example of database outreach to biologists via video. Database. 2011;2011:1–7.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support given by the “Agri-Food Research and Transfer Centre of the Water Campus (CITACA) at the University of Vigo (Spain)”.

Funding

This research was funded by the Autonomous Government of Galicia, Spain (project IN607A/013), and by the “Secretaría de Estado de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación”, Spain, within the projects AGL2015–67313-C2–1-R and AGL2015–67313-C2–2-R, which were co-financed with European Social Funds. R. Santiago acknowledges postdoctoral contract “Ramón y Cajal” financed by the “Secretaría de Estado de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación” and co-financed by the “Universidad de Vigo”, Spain, and the European Social Funds.

Availability of data and materials

The phenotypic data sets generated and analyzed in the current study are available upon request to the corresponding author. Vegetal materials are distributed to the scientific community by the NCRPIS upon request (https://www.maizegdb.org/data_center/stock?id=3100329).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB and RAM conceived the study; AB, LFS, RS and AC assisted in field experiments and data collection; AB and LFS performed statistical analyses of data and drafted the initial manuscript. AB edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Data distribution for fumonisin content in 2010 (left) and 2011 (right). (PNG 22 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Candidate Genes for each QTL. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Names of the panel inbreds along with their accession identifications at the North Central Regional Plant Introduction Station (NCRPIS). (XLS 40 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Samayoa, L.F., Cao, A., Santiago, R. et al. Genome-wide association analysis for fumonisin content in maize kernels. BMC Plant Biol 19, 166 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1759-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1759-1