Abstract

Background

CRISPR/Cas9 technology is one of the most powerful and useful tools for genome editing in various living organisms. In higher plants, the system has been widely exploited not only for basic research, such as gene functional analysis, but also for applied research such as crop breeding. Although the CRISPR/Cas9 system has been used to induce mutations in genes involved in various plant developmental processes, few studies have been performed to modify the color of ornamental flowers. We therefore attempted to use this system to modify flower color in the model plant torenia (Torenia fournieri L.).

Results

We attempted to induce mutations in the torenia flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) gene, which encodes a key enzyme involved in flavonoid biosynthesis. Application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system successfully generated pale blue (almost white) flowers at a high frequency (ca. 80% of regenerated lines) in transgenic torenia T0 plants. Sequence analysis of PCR amplicons by Sanger and next-generation sequencing revealed the occurrence of mutations such as base substitutions and insertions/deletions in the F3H target sequence, thus indicating that the obtained phenotype was induced by the targeted mutagenesis of the endogenous F3H gene.

Conclusions

These results clearly demonstrate that flower color modification by genome editing with the CRISPR/Cas9 system is easily and efficiently achievable. Our findings further indicate that this system may be useful for future research on flower pigmentation and/or functional analyses of additional genes in torenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Flower color is one of the most important traits in ornamental flowers, and plant breeders have devoted a great deal of effort to the production of varieties with new flower colors. Although these varieties have mainly been generated by traditional cross-breeding or tissue culture techniques such as embryo rescue to produce interspecific hybrids, several have also been produced using modern biotechnology methods, such as artificial mutagenesis by exposure to UV, ionizing radiation or chemical mutagens, and genetic transformation. For example, the production of flower-color mutants has been reported in various ornamental flowers, including cyclamens, Catharanthus and chrysanthemum, by ion-beam irradiation [1, 2]. We also recently induced a flower color change from blue to pink in Japanese gentian, with a frequency as high as 8.3%, by ion-beam irradiation [3]. The most problematic aspect of this technique, however, is that flower color cannot be predicted in advance, and which genes are mutated remains unknown in mutagenesis breeding. In particular, mutations in most cases are randomly induced, with several genes simultaneously mutated in various ways, such as by insertion/deletions (In/Dels), base substitutions and chromosome rearrangements, thereby hindering the effective acquisition of a desirable flower color. If desirable flower-color mutants are obtained, further screening of elite lines exhibiting no defects in other traits is required. Genetic transformation, in contrast, is the most straightforward approach to produce desired flower colors without changing other traits. In fact, blue-hued carnations and roses produced by genetic transformation have been commercialized by Suntory Ltd. for many years [4]. Similarly, a transgenic approach can be applied to improve various flower traits, including flower pigmentation, fragrance and shape, flowering time and disease resistance [5].

Flower color modification by genetic transformation has been attempted for several decades [6, 7]. In early years, white-colored flowers generated by antisense or RNAi targeting of structural genes, e.g. the chalcone synthase (CHS) gene, were produced in several plant species such as petunia, tobacco and chrysanthemum. Transcription factors such as MYB and bHLH have also been used as target genes for genetic engineering [8, 9]. Flower color mutants with deficiencies in certain genes are especially valuable to produce desirable flower colors in genetic engineering experiments. For example, one early study producing brick-red flowers in petunia used a triple mutant as a transformed host [10]. Blue-hued carnations or roses can also be produced by eliminating competition from the endogenous enzymes flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) and flavonol synthase (FLS); consequently, downregulation of these genes in addition to the introduction of the flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H) gene is necessary to accomplish the accumulation of high amounts of delphinidin-type anthocyanins [7]. Similarly, mutant lines are useful as breeding materials for the genetic engineering of interesting flower colors, but few materials are available in most floricultural species. Even if useful mutants exist, the incorporation of the mutant traits by traditional cross-breeding is time-consuming and arduous.

Many recent studies have focused on genome editing in higher plants [11,12,13]. One of the most powerful and reliable genome-editing methods is the CRISPR/Cas9-based system developed using the bacterial immune system. Flower color modification by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of the DFR-B gene was recently achieved in Japanese morning glory [14]. This technique can undoubtedly be adapted not only for basic studies but also for applied studies such as crop breeding. The efficiency of this system in various plant species is currently being optimized; these efforts include modification of Streptococcus pyogenes SpCas9 nuclease, application of new variants of the genome modifying system from other bacterial species and redesign of single-guide RNA [15]. Furthermore, a DNA-free genome editing system with preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins has been developed that may overcome GMO restrictions in plants [16]. New methods such as RNA-targeted genome editing and base editing by engineered deaminase have been developed more recently [17,18,19].

In this study, we attempted to modify flower colors by genome editing of a flavonoid biosynthetic-related gene using the basic CRISPR/Cas9 system. For this purpose, we used Torenia fournieri, a model plant widely applied for flower research [20]. We targeted the flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) gene, a key enzyme gene in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway (Additional file 1: Figure S1), because we had previously determined that an F3H mutation was responsible for the white flower color of a torenia cultivar [21]. F3H has also more recently been successfully edited using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in carrot calli [22], but its effect has not yet been evaluated in flowers. The results of the study reported here clearly demonstrate that the CRISPR/Cas9 system can be efficiently applied to modify flower color in torenia. Finally, we have also evaluated the efficiency and usefulness of genome editing for flower research.

Results

Flower pigmentation phenotypes of transgenic torenia plants

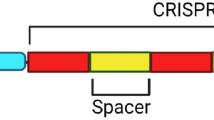

We constructed a binary vector using a plant codon-optimized S. pyogenes strain (pcoCas9) and a guide RNA-targeted exon 1 of the torenia F3H gene (Fig. 1) and then produced 24 transgenic torenia plants by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. After several subcultures, the transgenic plants set flowers in vitro within 8 months. The earliest blossoms were observed less than 4 months after Agrobacterium infection. Representative flowers are shown in Fig. 2. The plants, which exhibited several different flower colors, are summarized in Table 1. In particular, 4 of the 24 lines had violet flowers, the same as wild-type untransformed control plants. Fifteen lines produced faint blue (almost white) flowers, while three lines (nos. 22–24) bore pale violet flowers, and line no. 15 set violet or faint blue flowers depending on the propagated stems. Interestingly, line no. 7 produced variegated flowers, but the phenotype was unstable. In several of the faint blue flower-colored lines, a few blue spots were observed (e.g. lines no. 9, 15B and 16 in Fig. 1; Table 1).

Schematic diagram of the binary vector and the torenia target sequence in the torenia F3H gene. a Schematic diagram of the T-DNA region of pSKAN-pcoCas9-TfF3H used in this study. NPTII, expression cassette of NOSp-nptII-AtrbcsTer; 35Sp, CaMV35S promoter; pcoCas9, plant codon-optimized Cas9 [35]; HSPter, Arabidopsis heat shock protein 18.2 terminator [36]; RB, right border; LB, left border; AtU6p, Arabidopsis small RNA U6–26 promoter; TfF3HsgRNA, torenia F3H targeted single-guide RNA. pcoCas9 contains an intron derived from the intervening sequence 2 (IV2) of the potato St-LS1 gene [35]. b Genomic structure of the torenia F3H gene and exon 1 sequence. Boxes indicate exons, and lines between boxes indicate introns. Framed ATG indicates the start codon, and the gray box indicates the target site F3H sequence. The protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) is underlined. Primers used for PCR amplification are also shown

Sequence analyses of the F3H target region

First, fragments amplified by PCR using primers TfF3HU7 and TfF3HL371 were directly subjected to sequencing analysis. Typical results are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2. The sequence chromatogram of an untransformed WT plant contained a clear sequencing peak corresponding to the wild-type F3H sequence, whereas most transgenic plants showed sequence changes, such as single-base insertions, deletions or substitutions. Some lines, such as nos. 5, 6 and 23, had mixed-sequence chromatograms that were probably due to the presence of multiple edited sequences. Subcloning was also performed in some lines to confirm the sequences. According to the sequencing results, summarized in Table 1, all flower-color phenotypes coincided with the presence of mutated sequences of the F3H target region. More than 60% of transgenic lines (15/24) had flower color changes, from violet to faint blue (almost white). The faint blue flowers had mutations in both F3H alleles. Pale violet-flowered lines no. 23 and 24 contained two sequences: WT and + 1A alleles. The other pale violet line, no. 22, contained three sequences corresponding to -3 bp, + 1 T and + 1A alleles. In the case of torenia, single-base insertions were abundantly observed in edited sequences.

Because Sanger sequencing clearly revealed the results of genome editing in the target F3H region, we next performed a sequencing analysis on an Illumina Mi-seq next-generation sequencer to more efficiently obtain sequence information. Nine transgenic genome-edited torenia lines and the WT were selected and subjected to next-generation amplicon sequencing of the same F3H target region. The resulting data are summarized in Table 2 and Additional file 2. Sequence reads other than major reads were observed in all samples including the wild type; these reads represented less than 0.5% of total reads and were considered to be derived from PCR or NGS errors. The results of Sanger sequencing and NGS were basically consistent except for those of line no. 19. In line no. 19, a -2 bp edited sequence was also detected in addition to -32 bp editing determined by Sanger sequencing.

Cultivation in a closed greenhouse and pigment analysis

To investigate whether the modified flower colors were stable under natural growth conditions, we acclimatized and cultivated the faint blue-flowered transgenic genome-edited lines having mutations in both alleles (nos. 5, 9, 10 and 19) in a closed greenhouse. Their growth was found to be normal, and all tested transgenic genome-edited plants had the same faint blue flowers observed in in vitro flowering (Fig. 3a). The faint blue flowers continued to bloom more than 3 months and the flower color was stable under our cultivation conditions in the greenhouse. Other phenotypes, such as flowering time and plant height, were similar to the WT in all lines. The spectrum absorbance of petal extracts of these four lines displayed a very small peak absorbance at 530 nm, whereas Crown White (a completely white-flowered cultivar) showed none, which indicates the presence of residual anthocyanins in these transgenic genome-edited torenia lines (Fig. 3b). Relative anthocyanin contents were calculated from the absorbance data and are shown in Fig. 3c. These results also indicate that low but detectable levels of anthocyanins were present in the F3H-edited plants.

Flowers of transgenic genome-edited torenia plants cultivated in a closed greenhouse and results of pigment analysis. a Four biallelic transgenic genome-edited torenia plants were grown in a closed greenhouse. Pictures of typical flowers are shown. CrV and CrW indicate cultivars Crown Violet and Crown White, respectively. CrV was the host plant for transformation, and CrW was a white cultivar for comparison. b Pigment analysis by spectrophotometry. Left panel, absorbance spectra of 0.1% HCl–methanol extracts of flower petals (line no. 5, CrV and CrW) are shown in the left panel. Right panel, relative anthocyanin contents of petals of transgenic genome-edited torenia plants and an untransformed control plant (CrV) were determined. Values indicate averages of five flower petals ± standard deviation

Discussion

In this study, flower color modification using the CRISPR/Cas9 system was successfully achieved in torenia flowers. Namely, ca. 80% (20/24) of transgenic lines exhibited flower color changes, a sufficiently high efficiency for the practical use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in this plant species. This value is similar to that achieved by genome editing of the CRISPR/Cas9-targeted torenia RADIALIS (RAD1) gene controlling floral asymmetry [23]. In that study, 10 out of 12 transgenic lines showed stable phenotypes, but no detailed sequence analyses were performed except for two lines. In regards to flower color modification by genetic transformation in torenia plants, suppression of flavonoid biosynthetic genes has been reported in several studies. For example, inhibition of flower pigmentation was first achieved by the introduction of antisense CHS or DFR genes, which resulted in flower color changes in 0–89% of transgenic lines, but the degree of color lightening varied among lines [24]. RNAi-targeted CHS or ANS genes were then applied for flower color suppression, which revealed that RNAi was a more useful method to produce a stable white flower-color phenotype with high efficiency (more than 50%) in torenia [25, 26]. F3H genes have also been suppressed by RNAi to produce white flowers in torenia plants, but the efficiency has not been reported [27]. In our study, 20 transgenic T0 lines (primary transformants) displayed flower color changes. The edited F3H alleles frequently included homozygous and heterozygous biallelic mutations. With respect to the editing sequence pattern, single base insertions (+ 1 bp) were most frequently observed, with deletions such as -1 bp, − 2 bp and -32 bp also occurring in some lines. Su et al. [23] have actually reported the presence of edited TfRAD1 sequences with a 141-bp deletion or a single-base insertion in two analyzed lines. The pattern of editing may largely depend on the selected target sequences and the type of transformation system (i.e., via callus or direct shoots vs. floral dip). Further analysis is necessary to confirm whether or not CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing to transform torenia tends to always induce single-base insertions. In contrast, lines no. 23 and 24 had pale violet flowers and harbored a monoallelic mutation (i.e., only one allele was mutated, with the WT sequence remaining). This flower color may be due to the semi-dominant phenotype, in which F3H activity is partly functional because of the remaining normal allele. Alternatively, the mutated allele may induce silencing of the normal allele by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Line no. 15 actually had different-colored flowers (violet and faint blue) within a single plant, indicating the possibility of chimerism. The presence of three different mutated sequences in line no. 22 also suggests the chimeric nature of this line, although whether this chimerism was derived from an early editing event or occurred during subculture is unknown. Given that line no. 7 set variegated flowers and several lines had a few blue spots, genome editing can probably occur after shoot regeneration and during flowering. Chimerism has also been observed in CRISPR/Cas9 genome-edited flowers of morning glory [14] and rice callus [28]. Genome editing is thus likely ongoing in these transgenic genome-edited torenia lines even though most editing events are considered to occur at the early transformation stage. Further analysis is necessary to gain insights into the chimeric (mosaic) nature of CRISPR/Cas9 system transformation. Because flower color is a visible trait and observation at the single-cell level is possible under the microscope, our materials should be suitable for such studies.

Observation of flowering plants in a closed greenhouse and a pigment analysis uncovered low levels of anthocyanins in F3H-mutated petals. This result indicates that torenia can produce low amounts of anthocyanins even when F3H is mutated. The reason for this phenomenon is not fully understood, but most likely other endogenous enzymes can catalyze the transformation of flavanones to dihydroflavonols via an unspecific reaction. The F3H mutant of Arabidopsis has actually been reported to display a leaky phenotype, with the involvement of flavonol synthase (FLS) and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), both belonging to the 2-oxoglutarate dependent oxygenase family [29], suspected. In carnation, F3H deficiency causes pink flowers in some cultivars [30, 31]. Because further analysis is needed to confirm this hypothesis, we are currently producing F3H-edited transgenic tobacco and gentian plants.

Several methods currently exist to assess the outcome of genome editing, such as a PCR/restriction enzyme assay, high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis, and T7 Endonuclease I and TaqMan qPCR assays [32]. Although these methods are useful for screening mutations introduced by the CRISPR/Cas9 system, sequencing analysis provides the most direct evidence to confirm genome editing. Compared with the other methods, however, the cost is problematic. Instead of Sanger sequencing, we analyzed our nine lines of transformants by next-generation amplicon sequencing while indexing multiple samples. The results of NGS were basically consistent with those obtained by Sanger sequencing, thus indicating that NGS and bioinformatic analyses for effectively obtaining edited allele sequence information can save much time and labor. With both methods, however, error incorporation during PCR amplification and NGS must be taken into consideration. For example, sequencing error rates during amplicon sequencing by Illumina Miseq have been well studied [33]. In fact, our NGS results also contained many minor fragments possibly derived from such artificial errors (Table 2 and Additional file 2). In this study, such minor fragments constituted less than 0.5% of fragments at most and did not influence the identification of edited sequences.

As mentioned above, CRISPR/Cas9 is most certainly a valuable tool for flower research using torenia, as editing efficiency is comparably high and the time until flowering is short. The production of effective biallelic mutants enables us to perform gene functional analysis in primary T0 plants. We can obtain pale blue-flowered torenia plants by in vitro flowering as early as 4 months after inoculation with Agrobacterium. Novel editing tools such as RNA editing and nucleotide substitution by deaminase [17,18,19] are also promising approaches that we hope can be applied to torenia research in the near future.

Conclusions

Taken together, our results clearly show that the CRISPR/Cas9 system can efficiently transform flower color in torenia plants. This system will be useful for the functional analysis of genes involved in various traits, such as flower color and shape, flowering time and disease resistance. We hope that various studies on torenia will be performed using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in the future.

Methods

Plant materials and transformation

Torenia fournieri ‘Crown Violet’ was used as the transformation host, and the cultivar Crown White was also used as a control for pigment analysis. Both are clonal lines provided by Dr. Ryutaro Aida (National Institute of Floricultural Science, Japan) and also used in our previous study [21]. Plants maintained by in vitro culture were used for transformation as described previously [21]. Briefly, leaf sections were excised and co-cultivated with Agrobacterium harboring a pSKAN-pcoCas9-TfF3H vector (Fig. 1a) for 1 week. Kanamycin-resistant calli were selected, and regenerated shoots were transferred to rooting medium. After rooting, transgenic plants were cultured in vitro until flowering, and flower color was observed. After acclimatization, some transgenic genome-edited plants were grown in a closed greenhouse and cultivated until flowering.

Construction of a binary vector for genome editing

The binary CRIPSR/Cas9 vector, pSKAN-pcoCas9-TfF3H (Fig. 1), was constructed and used for plant transformation. Briefly, pSKAN-pcoCas9 was first constructed by replacing the uidA (gus) gene of pSKAN35SGUS [34] by the plant codon-optimized SpCas9 (pcoCas9) [35] purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA) and an Arabidopsis HSP18.2 terminator [36]. A synthesized single-guide RNA targeting the torenia F3H gene was then introduced to pSKAN-pcoCas by restriction enzyme treatment and ligation, resulting in pSKAN-pcoCas9-TfF3H (Fig. 1a). Target site was selected manually in the F3H coding region and located about 200 bp downstream from translation start codon (Fig. 1b). The vector was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA101 by electroporation.

Anthocyanin analysis

Flowers were collected from greenhouse-grown plants, and their petals were extracted with methanol containing 0.1% HCl. Anthocyanin contents were determined by measurement of OD at 530 nm spectrophotometrically.

Sanger sequencing analysis

Leaf extracts of transgenic plant lines were subjected to PCR using primer pairs TfF3HU7 (5′-AGCAGGACCACTAACCCTAACTTC-3′) and TfF3HL371 (5′- GGTGACTCGAAACAATGAAACCTC-3′) (Fig. 1b) with MightyAmp DNA polymerase (Takara Bio., Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After purification, the amplified fragments were directly subjected to Sanger sequencing analysis using a BigDye terminator ver. 1.1 cycle sequencing kit and the forward TfF3HU7 primer on an ABI PRISM 3130xl DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The sequence chromatograms were analyzed manually or using the DSDecode program [37]. Amplified fragments of some selected lines were also subcloned into PCR4-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced with M13 M4 or M13RV primers as described above.

NGS analysis

Genomic DNAs were isolated from leaf samples of in vitro grown transgenic torenia plants using the GeneElute Genome DNA Isolation system (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR amplification was performed using a KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMixPCR kit (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). Primers TfF3H1U7_57mer and TfF3H1L371_57mer (Additional file 1: Table S1) were used for the first PCR round, which was carried out under the following conditions: 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 20 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C and 30 s at 72 °C, and then 5 min at 72 °C. Conditions for the second PCR round were as follows: 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 12 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C and 30 s at 72 °C, and a final step of 5 min at 72 °C. The second PCR was performed using D50x and D70x primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) for indexing. Products from the two PCR rounds were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK). Amplification of the second set of PCR products was checked on a fragment analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies, Ankeny, IA, USA) using a High Sensitivity NGS Fragment Analysis kit. All PCR products were mixed at the same volume ratio. Concentrations of mixed PCR products, namely, a bulked library, were measured by qPCR using a KAPA Library Quantification kit. The final concentration of the bulked library was diluted to 6 pM. As a control, PhiX (Illumina control library version 2; Illumina, San Diego, USA) was spiked in the bulked library at 50% (v/v). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq system using a MiSeq Reagent v2 kit (500 cycles). The resulting raw sequence reads were preprocessed using the FASTX toolkit as follows. First, reads shorter than 40 bases were discarded, and the remaining reads were trimmed at 230 bases. Second, quality filtering of the remaining 40–230-base reads was performed using q20 and p80 parameters. Third, unpaired reads were discarded. Fourth, read pairs were merged into a single contiguous sequence (fragment) using a fastq-join script [38]. Finally, unique fragments were counted.

Abbreviations

- CRISPR:

-

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- F3H:

-

Flavanone 3-hydroxylase

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Akita Y, Morimura S, Loetratsami P, Ishizaka H. A review of research on ower-colored mutants of fragrant cyclamens induced by ion-beam irradiation. Horticult Int J. 2017;1:90–1.

Yamaguchi H. Mutation breeding of ornamental plants using ion beams. Breed Sci. 2018;68:71–8.

Sasaki N, Watanabe A, Asakawa T, Sasaki M, Hoshi N, Naito Z, Furusawa Y, Shimokawa T, Nishihara M. Evaluation of the biological effect of ion beam irradiation on perennial gentian and apple plants. Plant Biotech. 2018;35:249–57.

Tanaka Y, Brugliera F. Flower colour and cytochromes P450. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120432.

Noman A, Aqeel M, Deng J, Khalid N, Sanaullah T, Shuilin H. Biotechnological advancements for improving floral attributes in ornamental plants. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:530.

Nishihara M, Nakatsuka T. Genetic engineering of flavonoid pigments to modify flower color in floricultural plants. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:433–41.

Tanaka Y, Brugliera F, Kalc G, Senior M, Dyson B, Nakamura N, Katsumoto Y, Chandler S. Flower color modification by engineering of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway: practical perspectives. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74:1760–9.

Hichri I, Barrieu F, Bogs J, Kappel C, Delrot S, Lauvergeat V. Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:2465–83.

Falcone Ferreyra ML, Rius SP, Casati P. Flavonoids: biosynthesis, biological functions, and biotechnological applications. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:222.

Meyer P, Heidmann I, Forkmann G. Saedler H. a new petunia flower colour generated by transformation of a mutant with a maize gene. Nature. 1987;330:677–8.

Cao HX, Wang W, Le HT, Vu GT. The power of CRISPR-Cas9-induced genome editing to speed up plant breeding. Int J Genomics. 2016;5078796.

Haeussler M, Concordet JP. Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9: can it get any better? J Genet Genomics. 2016;43:239–50.

Schaeffer SM, Nakata PA. The expanding footprint of CRISPR/Cas9 in the plant sciences. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35:1451–68.

Watanabe K, Kobayashi A, Endo M, Sage-Ono K, Toki S, Ono M. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of the dihydroflavonol-4-reductase-B (DFR-B) locus in the Japanese morning glory Ipomoea (Pharbitis) nil. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10028.

Murovec J, Pirc Z, Yang B. New variants of CRISPR RNA-guided genome editing enzymes. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15:917–26.

Woo JW, Kim J, Kwon SI, Corvalan C, Cho SW, Kim H, Kim SG, Kim ST, Choe S, Kim JS. DNA-free genome editing in plants with preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:1162–4.

Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Essletzbichler P, Han S, Joung J, Belanto JJ, Verdine V, Cox DBT, Kellner MJ, Regev A, et al. RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature. 2017;550:280–4.

Cox DBT, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Franklin B, Kellner MJ, Joung J, Zhang F. RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science. 2017;358:1019–27.

Kim JS. Precision genome engineering through adenine and cytosine base editing. Nature Plants. 2018;4:148–51.

Nishihara M, Shimoda T, Nakatsuka T, Arimura G. Frontiers of torenia research: innovative ornamental traits and study of ecological interaction networks through genetic engineering. Plant Methods. 2013;9:23.

Nishihara M, Yamada E, Saito M, Fujita K, Takahashi H, Nakatsuka T. Molecular characterization of mutations in white-flowered torenia plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:86.

Klimek-Chodacka M, Oleszkiewicz T, Lowder LG, Qi Y, Baranski R. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing in carrot cells. Plant Cell Rep. 2018;37:575–86.

Su S, Xiao W, Guo W, Yao X, Xiao J, Ye Z, Wang N, Jiao K, Lei M, Peng Q, et al. The CYCLOIDEA-RADIALIS module regulates petal shape and pigmentation, leading to bilateral corolla symmetry in Torenia fournieri (Linderniaceae). New Phytol. 2017;215:1582–93.

Aida R, Yoshida K, Kondo T, Kishimoto S, Shibata M. Copigmentation gives bluer flowers on transgenic torenia plants with the antisense dihydroflavonol-4-reductase gene. Plant Sci. 2000;160:49–56.

Fukusaki E, Kawasaki K, Kajiyama S, An CI, Suzuki K, Tanaka Y, Kobayashi A. Flower color modulations of Torenia hybrida by downregulation of chalcone synthase genes with RNA interference. J Biotechnol. 2004;111:229–40.

Nakamura N, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Miyazaki K, Suzuki K, Tanaka T. RNAi suppression of the anthocyanidin synthase gene in Torenia hybrida yields white flowers with higher frequency and better stability than antisense and sense suppression. Plant Biotechnol. 2006;23:13–7.

Ono E, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Nakamura N, Fukui Y, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Yamaguchi M, Nakayama T, Tanaka T, Kusumi T, Tanaka Y. Yellow flowers generated by expression of the aurone biosynthetic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11075–80.

Mikami M, Toki S, Endo M. Comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 expression constructs for efficient targeted mutagenesis in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2015;88:561–72.

Owens DK, Crosby KC, Runac J, Howard BA, Winkel BS. Biochemical and genetic characterization of Arabidopsis flavanone 3β-hydroxylase. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46:833–43.

Dedio J, Saedler H, Forkmann G. Molecular cloning of the flavanone 3β-hydroxylase gene (FHT) from carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) and analysis of stable and unstable FHT mutants. Theor Appl Genet. 1995;90:611–7.

Mato M, Onozaki T, Ozeki Y, Higeta D, Itoh Y, Hisamatsu T, Yoshida H, Shibata M. Flavonoid biosynthesis in pink-flowered cultivars derived from 'William Sim' carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus). J Japan Soc. Hort Sci. 2001;70:315–9.

Peng C, Wang H, Xu X, Wang X, Chen X, Wei W, Lai Y, Liu G, Ian G, Li J, et al. High-throughput detection and screening of plants modified by gene editing using quantitative real-time PCR. Plant J. 2018;95:557–67.

Schirmer M, Ijaz UZ, D'Amore R, Hall N, Sloan WT, Quince C. Insight into biases and sequencing errors for amplicon sequencing with the Illumina MiSeq platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e37.

Nakatsuka T, Saito M, Yamada E, Fujita K, Kakizaki Y, Nishihara M. Isolation and characterization of GtMYBP3 and GtMYBP4, orthologues of R2R3-MYB transcription factors that regulate early flavonoid biosynthesis, in gentian flowers. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:6505–17.

Li JF, Norville JE, Aach J, McCormack M, Zhang D, Bush J, Church GM, Sheen J. Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:688–91.

Nagaya S, Kawamura K, Shinmyo A, Kato K. The HSP terminator of Arabidopsis thaliana increases gene expression in plant cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:328–32.

Liu W, Xie X, Ma X, Li J, Chen J, Liu YG. DSDecode: a web-based tool for decoding of sequencing chromatograms for genotyping of targeted mutations. Mol Plant. 2015;8:1431–3.

Aronesty E. Comparison of sequencing utility programs. Open Bioinform J. 2013;7:1–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ryutaro Aida (National Institute of Floricultural Science, Japan) for providing us with the torenia materials and the transformation protocol. We thank Mses. Yoshimi Kurokawa and Rie Washiashi, Iwate Biotechnology Research Center, for technical assistance with production and cultivation of transgenic torenia plants. We also thank Mr. Hiroki Yaegashi, Iwate Biotechnology Research Center, for technical help in the analysis of NGS data. We thank Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Iwate Prefecture and also in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (nos. 15H04453 and 16 K18654). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN conceived and designed the experiments. AH and AW performed the experiments. MN also performed some of the experiments. KT contributed to the NGS analysis. KT and MN contributed to data analysis and interpretation. MN supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. KT critically read and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Schematic representation of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in torenia. ANS, anthocyanidin synthase; C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; CHS, chalcone synthase; 4CL, 4-coumarate: CoA ligase; DFR, dihydroflavonol 4-reductase; DHK, dihydrokaempferol; DHM, dihydromyricetin; DHQ, dihydroquercetin; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase (target gene in this study); F3′H, flavonoid 3′ -hydroxylase; F3′,5′H, flavonoid 3′, 5′ -hydroxylase; FNSII, flavone synthase II; GT, glucosyltransferase; MT, methyltransferase; PAL, phenylalanine ammonia lyase. Figure S2. Sequence chromatograms of the TfF3H gene in different transgenic torenia lines. PCR products were subjected to Sanger sequencing using the TfF3HU7 primer. The region of the sequence chromatogram including the target site is enlarged. Transgenic line numbers are shown on each chromatogram. WT indicates the wild-type sequence (cv. Crown Violet). Table S1. Primers used for multiplex amplicon sequencing by NGS. (PDF 394 kb)

Additional file 2:

The results of next-generation amplicon sequencing of cv. Crown Violet and nine genome-edited torenia lines. Numbers after sequence names in the Excel worksheets are sequential serial numbers and read counts of each fragment. (XLSX 668 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishihara, M., Higuchi, A., Watanabe, A. et al. Application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for modification of flower color in Torenia fournieri. BMC Plant Biol 18, 331 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1539-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1539-3