Abstract

Background

The basil (Ocimum spp.) genus maintains a rich diversity of phenotypes and aromatic volatiles through natural and artificial outcrossing. Characterization of population structure and genetic diversity among a representative sample of this genus is severely lacking. Absence of such information has slowed breeding efforts and the development of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) with resistance to the worldwide downy mildew epidemic, caused by the obligate oomycete Peronospora belbahrii. In an effort to improve classification of relationships 20 EST-SSR markers with species-level transferability were developed and used to resolve relationships among a diverse panel of 180 Ocimum spp. accessions with varying response to downy mildew.

Results

Results obtained from nested Bayesian model-based clustering, analysis of molecular variance and unweighted pair group method using arithmetic average (UPGMA) analyses were synergized to provide an updated phylogeny of the Ocimum genus. Three (major) and seven (sub) population (cluster) models were identified and well-supported (P < 0.001) by PhiPT (ΦPT) values of 0.433 and 0.344, respectively. Allelic frequency among clusters supported previously developed hypotheses of allopolyploid genome structure. Evidence of cryptic population structure was demonstrated for the k1 O. basilicum cluster suggesting prevalence of gene flow. UPGMA analysis provided best resolution for the 36-accession, DM resistant k3 cluster with consistently strong bootstrap support. Although the k3 cluster is a rich source of DM resistance introgression of resistance into the commercially important k1 accessions is impeded by reproductive barriers as demonstrated by multiple sterile F1 hybrids. The k2 cluster located between k1 and k3, represents a source of transferrable tolerance evidenced by fertile backcross progeny. The 90-accession k1 cluster was largely susceptible to downy mildew with accession ‘MRI’ representing the only source of DM resistance.

Conclusions

High levels of genetic diversity support the observed phenotypic diversity among Ocimum spp. accessions. EST-SSRs provided a robust evaluation of molecular diversity and can be used for additional studies to increase resolution of genetic relationships in the Ocimum genus. Elucidation of population structure and genetic relationships among Ocimum spp. germplasm provide the foundation for improved DM resistance breeding strategies and more rapid response to future disease outbreaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The genus Ocimum is estimated to contain approximately 64 herbaceous annual and perennial plant species [1]. The primary center of diversity is described as being in Tropical Africa [2], while a secondary center exists in Tropical Asia and a tertiary center exists in the New World tropics [2, 3]. A number of species are cultivated and processed throughout the world for application in medicinal, dietary supplement, essential oil, food flavoring and culinary industries [4]. Ocimum basilicum L., sweet basil, is among the most economically important culinary herbs in the United States, Europe and Israel [5]. Plant breeding efforts have largely targeted sweet basil for improved disease resistance [6], chilling tolerance [7] and novel volatile profiles (chemotypes) [8].

Ocimum spp. demonstrate relatively high rates of outcrossing in the presence of pollinators [9], while readily self-pollinating in their absence. The flexibility of this reproductive system has been exploited by natural and artificial selection, likely serving as a catalyst for morphological and volatile diversification of Ocimum spp. [4]. In addition, cytological investigation suggests this genus has also undergone extensive genome augmentation resulting in ploidy variation. While the x = 12 basic chromosome number is considered stable in tetraploid (2n = 4× = 48) O. basilicum, different ploidies have been reported across other Ocimum species [10]. Dual basic chromosome numbers of 8 and 12 have been proposed for two major ‘Basilicum’ and ‘Sanctum’ groups, respectively [11]. More recently, studies involving nuclear DNA content support the hypothesis of x = 12 as the genus-wide basic chromosome number with some cases of aneuploidy [12, 13]. This explanation accounts for dysploidy, which has proven to be a persistent phenomenon in plant evolutionary biology [14]. The 386 Mbp O. tenuiflorum (syn. O. sanctum) genome was reported to be a diploid (2n = 2× = 16) supporting the existence of an x = 8 basic chromosome number and suggesting O. tenuiflorum is a diploid species [15]. Thus, competing theories of major genome structure remain prevalent in the Ocimum genus.

Examination of chromosome pairing behavior suggests allopolyploidy likely explains the polyploid genome structure in basil [10, 11]. For instance, karyological investigation of O. basilicum and O. basilicum x O. americanum F1 hybrids found no evidence of tetravalent and little trivalent formation (4-8% of pollen mother cells) demonstrating high levels of preferential pairing within sub-genomes [11]. Relatively high levels of inter-specific hybridization [9] suggest allopolyploid formation to be more likely than autopolyploidy [16]. This hypothesis is also supported by genotype data from simple sequence repeat (SSR) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers in the O. basilicum MRI x SB22 F2 mapping family demonstrated that disomic segregation providing molecular evidence for an allotetraploid (AABB) O. basilicum [17].

In addition to variation in ploidy [10, 18], a variety of factors including unknown geographic origin and phenotypic diversity complicate classification of relationships among O. basilicum and the greater Ocimum genus. Taxonomical incongruencies are also widespread throughout the literature and among seed distributors. Furthermore, absence of standardized descriptors or voucher specimens for particular cultivars has been particularly problematic in classifying O. basilicum [1]. Species of economic salience such as O. x citriodorum, O. americanum and O. basilicum var. citriodorum are cited interchangeably throughout the literature making comparison across studies challenging [19]. Despite attempts to standardize nomenclature [19, 20] the species epithets continue to be used redundantly.

Morphological characters and volatile composition (chemotype) have been used to estimate genetic diversity in the Ocimum genus [21,22,23,24]. Classification based on phenotypic characters is problematic in that homologous similarities may be difficult or impossible to discriminate from traits resulting from convergent evolution [25]. Reliance upon analyses using these metrics may be particularly damaging in the context of plant breeding, which relies heavily upon genetic relationships among germplasm to make informed decisions with regard to selection and crossing decisions [26]. Nevertheless, the most comprehensive study of Ocimum to date remains that of Paton et al., which relied exclusively upon morphological characters [1]. Results of this study delineated three major divisions in the genus or subgenera corresponding into Ocimum, Nautochilus and Gymnocium [1]. Subgenera Ocimum is further divided into three sections including Gratissima, Hiantia, and Ocimum, where O. basilicum and O. americanum was placed [1].

Molecular phylogenetic approaches have employed RAPD and/or AFLP markers to determine relationships among nine [27], twelve [28], twenty-two [18], twenty-eight [12] and thirty seven [2] Ocimum spp. accessions. DNA markers from three plastid regions were used by Paton et al. to classify 12 Ocimum spp. accessions within the Lamiaceae family [3]. More recently, inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers were found to have higher polymorphism information content (PIC) and greater resolving power than chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) psbA-trnH markers following cluster analysis of 12 accessions representing 8 Ocimum spp. [29]. Despite being the preferred marker systems for phylogenetic analyses, neither SSR nor SNP markers have been used to classify relationships among Ocimum spp. accessions. SSRs are considered advantageous because they are multi-allelic, polymorphic, reproducible, ubiquitous throughout the genome and amenable to high-throughput genotyping with multiplexed PCR [30]. Expressed sequence tag (EST) derived SSRs (EST-SSRs) are particularly desirable for genetic diversity and mapping studies due to their location in coding regions and transferability across related germplasm [31, 32]. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) O. basilicum EST library was recently used to develop polymorphic SSRs and genotype the MRI x SB22 mapping population [17].

The deficit of available sweet basil genetic and genomic resources relative to other cultivated plant species has been highlighted in recent years by a worldwide downy mildew (DM) epidemic caused by the oomycete pathogen Peronospora belbahrii [33, 34]. As demonstrated by extensive breeding across plant species affected by downy mildew, deployment of genetic resistance is an essential management strategy for effective disease control [35,36,37]. Recent reports of Mefenoxam resistant P. belbahrii isolates in Israel [38] and Italy [39, 40] exacerbate the need for resistant cultivars. However, development of resistant sweet basil varieties has been dramatically slowed by a severe lack of knowledge regarding genetic similarity between elite O. basilicum and exotic Ocimum spp. germplasm rich in sources of resistance [41,42,43]. This has rendered attempted introgression of resistant loci into sweet basil accessions subject to rudimentary trial and error by laborious cross-pollinations between elite and exotic breeding lines. Among 27 F1 hybrids evaluated by Ben-Naim et al., those considered ‘highly resistant’ were completely sterile [41].

Population structure is among the analyses most needed to better elucidate relationships among Ocimum spp. Model-based clustering is a powerful analysis method frequently used to infer association of individuals into distinct populations from multilocus data sets [44]. Association of germplasm into distinct populations provides essential a priori information needed to avoid issues of sterility while monitoring potential narrowing of the genetic pool among breeding populations. Furthermore, detection of cryptic population structure is an important prerequisite to association mapping (AM) of alleles with traits of interest (i.e. disease resistance) by avoiding false positive associations [44, 45]. Identification of population structure and estimation of genetic diversity among Ocimum spp. is needed to provide a more robust breeding response to future biotic or abiotic stresses.

In this study no designations of species/relationships are considered to provide an unbiased update of basil phylogenetics and first insights into population structure. We hypothesized that SSR markers developed from the available NCBI EST database could be employed to increase resolution of genetic relationships among a diverse panel of 180 Ocimum spp. accessions by population structure and genetic diversity analyses. Evaluation of these accessions for response to downy mildew provides insight into the distribution of downy mildew resistance within the Ocimum genus and has important implications for disease resistance breeding strategies.

Results

Response to Peronospora belbahrii

Significant differences (P < 0.001) were detected among 180 genotypes evaluated for response to DM (Additional file 1). Eighty-two accessions (46%) demonstrated a mean DS < 1.0 (considered resistant) of which 33 (18%) exhibited no sporulation (DS = 0). A large proportion (17%) of the accessions with mean DS < 1.0 were Rutgers breeding lines with MRI-conferred DM resistance (DMMRI). DM susceptibility was widespread, however, with 71 accessions (40%) having DS ≥ 3.0 (considered highly susceptible). The remaining 26 accessions (15%) were in an intermediate range of DS between 1 (10%) and 3 (50%) representing levels of DM tolerance. A single accession, PI 511865, segregated for response to DM indicating heterozygosity among loci controlling resistance in this accession.

EST-SSR polymorphism

The 20 EST-SSR markers used in this study were pre-screened for unambiguous PCR amplification and demonstrated a low percentage of null genotypes. A list of DNA sequence and melting temperatures (Tm) associated with EST-SSR markers can be found in Additional file 2. A minimum of 90% and an average of 96% of individuals were successfully genotyped across all EST-SSR markers. A total of 269 unique alleles were amplified across the 180 Ocimum spp. panel and 2 outgroup Nepeta cateria accessions (CN3 and CR9). The average PIC across 20 EST-SSR markers was 0.14, ranging from 0.01 to 0.48 and 6 to 24 alleles per marker (locus) (Table 1). The average number of alleles/locus across the full panel was 1.86 (Table 2).

Population structure and allele frequency

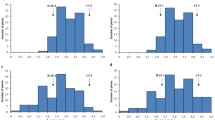

Primary model-based clustering (population structure) analysis provided unambiguous evidence (Additional file 3) for three major clusters k1 (n = 90), k2 (n = 16) and k3 (n = 36) (Fig. 1a). The remaining 38 accessions were considered admixed due to qI < 0.70 and/or genotypes of bi-parental origin from different clusters (Additional file 1). The average number of alleles per locus among clusters differed with values of 1.75, 2.23 and 1.34 corresponding to k1, k2 and k3, respectively (Table 2). Furthermore, clear differences were observed in the distribution of alleles per locus among clusters derived from primary population structure analysis. The majority of loci in the k1 cluster had 2 alleles (57%), nearly twice the 33% observed for single-allele loci. A more even distribution was observed in the k2 cluster with 22%, 37% and 36% for one, two and three alleles per locus. This rate of tri-allelic loci is in stark contrast to the < 1% in k1 and k3 clusters and suggests three homozygous, homeologous loci among a proportion of markers in k2 cluster. A majority of loci in k3 cluster were mono-allelic, twice that of the 30% bi-allelic loci. Finally, the number of alleles for loci of admixed accessions was relatively evenly distributed from 1 to 4 ranging from 18% to 32%. Five alleles were observed in an additional 4.3% of admixed loci. A total of 1812 alleles and an average of 2.58 alleles per locus (highest among all clusters) were detected for the 38 admixed accessions indicating heterozygosity.

Primary and nested population structure for 180-accession panel of Ocimum species. Primary and secondary (nested) model-based clustering analysis using Structure ver 2.2.3 software for panels of Ocimum spp. accessions using 20 EST-SSR markers. a Major clusters (K = 3) (top histogram) and sub-clusters (K = 7) (bottom histogram) derived from primary and nested clustering iterations. Ten accessions were admixed and nested population structure could not be inferred due to unknown parentage of admixed primary cluster membership (white bars). b Major clusters (K = 1) (top histogram) and sub-clusters (K = 2,5,7) (bottom three histograms). ΔK statistic values for K = 2-10 (right). Accessions are ordered according to the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic average (UPGMA) clustering

Secondary (nested) population structure analysis provided evidence for seven clusters (K = 7) among 142 non-admixed accessions (Fig. 1a). Two (K = 2) and three (K = 3) sub-clusters within k2 (k2.1 and k2.2) and k3 (k3.1, k3.2 and k3.3.), respectively, were strongly supported by the ΔK statistic (Additional file 4). Greatest support was provided for two (K = 2) sub-clusters, k1.1 and k1.2, among the 90-accession k1 primary cluster containing commercial sweet basil accessions. However, evidence was also provided for five (K = 5) and seven (K = 7) sub-clusters (Fig. 1b), suggesting cryptic population structure extant within this most economically important grouping. Nested population structure could not be determined for 9 accessions with admixed cluster membership from k1 and k3. Among these accessions, qI for either cluster (k1 or k3) failed to exceed 0.7 and could not be assigned due to unknown parentage. An additional 12 accessions had qI < 0.70 (Additional file 1) after being subjected to the nested population structure analysis and were considered admixed.

The average (Table 2) and distribution of the alleles per locus for sub-clusters was similar to the major primary clusters of k1 and k2. The range of alleles per locus among k1, k2 and k3 sub-clusters were 1.74-1.76, 2.18-2.27 and 1.30-1.41, respectively, indicating a high level of consistency with regard to allelic diversity. Interestingly, a relatively high percentage (11.2%) of null alleles occurred among accessions of sub-cluster k3.2.

Molecular variance

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was performed using 142 and 130 non-admixed accessions determined by primary and nested model-based cluster analysis, respectively. Inter-population differentiation was supported at the P < 0.001 level for primary and nested population structure with ΦPT values of 0.433 and 0.344, respectively (Table 3). The molecular variance due to differences within populations for nested clustering was 66% as compared to 57% from primary clustering. All pairwise ΦPT values for (K = 3) clusters were significantly different (P < 0.001) (Table 4). The majority of pairwise ΦPT values were highly significant (P < 0.001) for the seven (K = 7) clusters derived from nested analysis (Table 5). However, k3.1, k3.2 and k3.3 failed to demonstrate evidence for population differentiation based on AMOVA results (Table 5). These three sub-clusters contributed 51% of the total within population sum of squares (SSWP) while representing only 5.4% of the accessions included in the AMOVA (data not shown). Thus, high within population genetic variation coupled with a lower sample size may have lowered resolution for differentiation of these sub-clusters.

Characterization of genetic relationships

A cophenetic correlation value of r = 0.934 indicated strong goodness of fit [46] between the genetic similarity matrix used and the UPGMA dendrogram generated. Furthermore, the UPGMA dendrogram is in agreement with the placement of accessions for all major clusters (K = 3) determined by population structure analysis (Fig. 2a-b). The k1 cluster demonstrated generally lower genetic diversity as evidenced by high Jaccard similarity coefficient values (Fig. 2a). Importantly, accessions within the k1 cluster largely grouped consistent with known pedigree information available for 61% of accessions. The k2 cluster divides, according to nested population structure, into two clades of comparable genetic diversity. Although delineation of k3 into three sub-clusters was not supported by AMOVA, high bootstrap support values provide evidence of distinct groupings with high statistical backing (Fig. 2b). UPGMA grouping among k1 accessions did not demonstrate the same level of bootstrap support, however, this was not unexpected considering the ambiguity of nested model-based cluster analysis results.

Primary population structure and UPGMA clustering for 180-accession panel of Ocimum species. Unweighted pair group method using arithmetic average (UPGMA) dendrogram aligned with primary model-based clustering of Ocimum spp. 180-accession panel and 2 outgroup accessions (1 and 2) using 20 EST-SSR markers. Genetic distance was calculated using the Jaccard Similarity Coefficient (x-axis) and bootstrap support values are the result of 1000 permutations with support value greater than 0.500 shown. Three clusters (K) were inferred using Structure ver 2.2.3 and membership to each cluster is represented by proportion of yellow, orange or blue colors within horizontal lines corresponding to each accession. Numbers right of membership histograms correspond to accessions. Response to downy mildew is indicated resistant (R) = DS < 1.0, intermediate (I) = 1.0 < DS < 3.0 or susceptible (S) = DS > 3.0. Accessions with response R* share a single source of resistance conferred by accession MRI. The figure is divided into two segments a (left) and b (right)

The k1 cluster roots to a single major node that can be further divided into three distinct groups (Fig. 2a). This k1 cluster includes a commercial sweet basil clade that begins with ‘Caesar’ (Accession 3) and ends with ‘Lettuce Leaf Heirloom’ (Accession 31). Included are all accessions classified as O. basilicum such as the commercially important variety ‘Nufar’ (acc. 19) originally developed for FOB resistance and widely cultivated worldwide. In addition, all chilling (acc. 8-16) and FOB (acc. 13, 20-23, 27) tolerant Rutgers breeding lines are included in this group (Fig. 2a). A second major k1 clade includes two lineages RUMS (acc. 33-39) and RU4S (acc. 40-46, 48-59) (Fig. 2a) derived from breeding for DMMRI resistance. The resistant genotypeMRI (acc. 47) is centrally located among accessions in these lineages. USDA-GRIN accession PI 197442 (acc. 60) and all remaining k1 accessions (Fig. 2a) vary substantially in phenotype and aromatic volatile composition (data not published). Accessions in this k1 clade are primarily cultivated for specialty or ornamental markets with the exception of ‘Eleonora’ (acc. 69), a variety marketed for commercial fresh market consumption.

A k1 x k2 admixed, hybrid clade is supported by UPGMA analysis and can be observed at the top of Fig. 2b. This clade includes F1, F2 or F2:3 progeny with low or no fertility from a k1 x k2 bi-parental cross. PI 172996 (acc. 116) and ‘Sweet Dani’ (acc. 115) comprise all k2 parents with the exception of RU_SB22XLIME_F1 (acc. 97) and PI_652060XRU_SB17_F1 (acc. 98).

The k2 cluster corresponds to a major clade, which is further divided into two groups (Fig. 2b). Nested population structure analysis (Fig. 1a) and bootstrap support values (0.504 and 0.744) (Fig. 2b) are both in agreement with this sub-division. Accessions in this cluster are described by their sources as O. basilicum, O. citriodorum or O. americanum (Additional file 1). Three accessions cluster separately from all other k2 accessions and constitute a k2 x k3 hybrid grouping. Another k1 x k3 admixed clade is well-supported (0.938) and includes three F1 hybrids derived from a cross between DM resistant k3 parent ‘Spice’ (acc. 139) and three different k1 accessions. Two additional USDA-GRIN accessions, PI 414201 (acc. 140) and PI 414203 (acc. 141), are included in this clade and parentage is unknown.

Although the division of k3 into sub-clusters k3.1, k3.2 and k3.3 suggested by nested population structure analysis was not supported by the pairwise ΦPT estimates (Table 5), UPGMA provides evidence of clear delineations within this major cluster (Fig. 2b). The k3.1 cluster includes 7 phenotypically indistinguishable accessions sourced from commercial seed companies and the USDA-GRIN. This cluster is highly supported (1.00) and evidently an autonomous population (Fig. 1a; Fig. 2b). Another well-supported clade (0.997) is the k3.2 cluster (Fig. 1a; Fig. 2b), which includes 11 accessions beginning with PI 500952 (acc. 175) through PI 500942 (acc. 171). UPGMA analysis suggests this cluster represents a rather substantial juncture from the rest of the panel as it and subsequent clades are considered more basal than even the two Nepeta cataria outgroup accessions CN3 and CR9 according to UPGMA clustering. The k3.2 cluster is phenotypically homogenous and labeled O. x africanum according to the USDA-GRIN system. The k3.3 cluster includes basal most clades of the UPGMA dendrogram and the highest levels of genetic diversity based on Jaccard Similarity Coefficient genetic distance estimates shown as branch lengths in Fig. 2b. All accessions within this clade, supported by a 0.509 bootstrap value, are classified O. gratissimum according to their sources (Additional file 1). Within this clade bootstrap support values of 0.875, 0.977 and 0.897 support grouping of three more closely related pairs of accessions (Fig. 2b). PI 511865 (acc. 182) is labeled O. selloi and groups (0.980) with the phenotypically similar ‘Green Pepper Basil’ (acc. 181) (Fig. 2b). O. gratissimum and O. tenuiflorum accessions were used as outgroups in a previous AFLP-based assessment of basil phylogenetics [12], but did not include O. selloi found to be more basal in this study.

A number of additional accessions have membership to the k3.3 sub-cluster yet are more distally located from the basal end of the dendrogram (Fig. 1a). This includes phenotypically similar PI 652052 (acc. 145) and ‘Camphor’ (acc. 149); the former is classified O. x africanum by the USDA-GRIN, but more likely O. kilimandsharicum based on morphology and as described by Ben-Naim et al. [41]. These accessions group within a clade supported by a bootstrap support value of 0.907 (Fig. 2). A second, well-supported (0.867) clade included those with inferred ancestry to k3.3 (Fig. 1a). These accessions are classified O. tenuiflorum by commercial and USDA-GRIN sources (Additional file 1). Strong bootstrap support and phenotypic homogeneity among these two sets of accessions indicate UPGMA best resolves these k3 relationships.

Geographic distribution among clusters

In contrast to the greater panel, information regarding origin is available for the majority of k3 accessions (Additional file 1). All accessions in the k3.2 cluster were collected in Zambia indicating this grouping may be native to south-central Africa. Accessions in k3.1 and k3.3 are far less geographically congruent. Sub-cluster k3.3 includes diverse New and Old World geographic collections ranging from South America (PI 511865; Uruguay) to South East Asia (PI 652055; Sri Lanka) to Sub-Saharan Africa (PI 652064; Tanzania). The collection locations of four known accessions in k2.1 are split between Turkey (PI 172996; PI 172998) and Iran (PI 253157; 296391) suggesting a Middle-Eastern grouping. The remaining k2.1 accessions are cultivars with unknown parentage developed for a volatile composition high in monoterpenoids geranial and neral (i.e. citral). The k2.2 sub-cluster includes PI 652060 and PI 652061 collected in Pakistan and India, respectively, however, geographic origin of the remaining five accessions are unknown. The k1 cluster is comprised of largely commercial and Rutgers breeding lines in which parentage or geographical origin of parents is unknown. Ten of 12 USDA-GRIN accessions were collected in Turkey, Iran or Macedonia.

Distribution of DM resistance

Two unique sources of DM resistance (mean DS < 1.0), MRI (acc. 47) and Kivumbisi Lime x RUSB_17 F1 (acc. 83), were identified in the major cluster k1. The former accession has been used to develop DMMRI resistant breeding lines, while the latter is a sterile F1 hybrid with DM resistance conferred from the admixed accession 153 ('Kivumbisi Lime'). Apart from these two sources of resistance, the k1 cluster was largely DM susceptible with a mean DS of 3.6. Seven accessions demonstrated an intermediate response to DM (1.0 < DS < 3.0) and may be incorporated into breeding strategies targeting durable resistance [26].

The frequency of DM intermediate and resistant accessions increased with genetic distance from the k1 cluster. Intermediate resistance was observed among the majority of k2 accessions reflected by the 2.27 mean DS for this cluster. Interestingly, the k2.1 mean DS of 1.5 was lower than for k2.2 (mean DS = 3.4) for which the lowest DS was 2.9 (Fig. 3). Major cluster k3 is the primary source of DM resistance (mean DS = 0.36) with 29 resistant, 4 intermediate and one susceptible genotype. The highly supported (bootstrap = 0.867) clade of four accessions 156 - 159 exhibited hypersensitive response (HR). This response was not completely effective in preventing sporulation for these accessions such as 159 (PI 652057) (DS = 2.57) (Additional file 1).

Fourteen F1 hybrid accessions developed from DM resistant parents demonstrated resistance with the exception of SB17 x 172996 F1 (acc.100) with DS = 2.75. These results are in agreement with previous evaluation of F1 progeny providing corroborating evidence of dominant gene action [41]. Three k1 x k3 DM resistant F1 hybrids developed from ‘Spice’ (acc.133), ‘Kivumbisi Lime’ (acc. 153) and ‘Camphor’ (acc. 149) exhibit introgressed k3 resistance but were completely sterile. Hybrids from k1 accessions crossed with DM resistant and intermediate k2.1 accessions PI 172996 (acc. 116) and ‘Sweet Dani’ (acc. 115) demonstrated low fertility that could be overcome, however, an intermediate and susceptible response was observed for the respective F1 progeny (Additional file 1). Thus, unlike k3 accessions resistance did not appear to be under dominant gene control and requires further investigation to characterize the mechanism of DM response.

Discussion

Population structure and genetic diversity

Model-based and UPGMA clustering analyses provide evidence of three distinct delineations and 15.6% admixture among the 180 Ocimum spp. accession panel. Nested population structure analysis provides additional evidence for seven sub-populations. Greatest support (ΔK) was provided for two distinct populations (K = 2) nested within the most economically important O. basilicum k1 cluster. However, the possibility of five and seven sub-populations could not be discounted (Fig. 1b). Cryptic population structure in the k1 cluster may be attributed to extensive interbreeding, which is particularly prevalent in the O. basilicum species [47]. High levels of admixture were also observed for the K = 5 and K = 7 population models (Fig. 1b), further supporting the exchange of genomic content potentially as a function of natural and purposeful outcrossing. This is most evident in the k1.2 cluster, where both admixture (Fig. 1b) and genetic distance increase (Fig. 2a) proceeding towards the basal end of the dendrogram containing a large proportion of cultivars and USDA-GRIN accessions (Additional file 1). These results indicate plant breeding and natural outcrossing have maintained some level of genetic diversity within this economically salient cluster of accessions.

The k1 cluster was the largest in this study with 90 accessions, yet best evidence was provided for only two sub-clusters, which was also the case for the 16-accessions in k2. Furthermore, the 36-accession k3 cluster resolved into three sub-clusters and may potentially contain additional populations based on interpretation of UPGMA analysis (Fig. 2b). While these results do not necessarily suggest a bottleneck in k1, the k2 and k3 clusters clearly exhibit far greater genetic diversity. Introgression of accessions from the k2 and k3 clusters would be advantageous in broadening the k1 (O. basilicum) gene pool.

Taxonomical discrepancies

Results of this study find genetic distance and population inference is often not correlated with reported accession collection location, phenotype or even species epithet. Conflicting and redundant nomenclature in the literature, the USDA-GRIN system and commercial seed sources have confounded accurate species-level assignment to important Ocimum spp. accessions [24]. Phenotype appears to be somewhat predictive of genotype in clusters k3.1 and k3.2, however, leaf shape, habit, flower morphology and volatile composition are clearly heterogeneous among the remaining sub-clusters. For instance, k2.1 accessions 115 ('Sweet Dani') and 116 (PI 172996) group within a single clade (0.553), however, Sweet Dani exhibits no anthocyanins and a volatile composition that is 68% citral [8], while PI 172996 exhibits leaf and stem anthocyanins and a volatile composition 91% methyl chavicol [USDA-GRIN]. Meanwhile, k1.2 cluster accesions 77 ('Queenette') and 78 ('Sweet Thai') contain stem anthocyanins and high methyl chavicol comparable to PI 172996. Although phenotype-based classification may provide some predictive measure of genetic relatedness, applications such as plant breeding require highly accurate and precise understanding of relations among accessions in order to construct effective selection strategies.

Ploidy and reproductive barriers

Interesting differences in the mean and distribution of alleles per locus were observed among major and sub-clusters in this study. The majority of non-admixed accessions included in the panel are considered highly inbred and therefore homozygous across loci. Given this general assumption, some inferences can be made with regard to ploidy. A majority bi-allelic loci among k1 accessions suggests this cluster is an allotetraploid with two homozygous loci representing two sub-genomes. This system has been previously observed for the well-characterized allotetraploid genomes of Brassica napus [32] and Gossypium hirsutum [48]. One and two alleles per locus were observed in 33 and 57% of loci in the k1 cluster, respectively. These results are similar to the distribution of alleles per locus in a 240 EST-SSR marker survey using inbred k1 genotypes SB22 and MRI, in which a polymorphic subset also demonstrated disomic inheritance [17].

Among accessions in the k2 cluster, a 36% rate of three alleles per locus provides evidence of three homeologous loci, suggesting an allohexaploid genome. Previous investigations of cytology and nuclei acid content for the species O. africanum (syn. O. citriodorum) [20] suggested an allohexaploid (2n = 6× = 72) genome structure [11, 13, 18, 19]. Allelic distribution and cluster analysis in this study both support the hypothesis of an allohexaploid O. africanum k2 cluster and a need for nomenclature to be standardized across these accessions. Confusingly, USDA-GRIN accessions in the strongly supported (0.997) sub-cluster (k3.2) are labeled as O. xafricanum, illustrating the continued Ocimum spp. taxonomic issues and a need for revision of nomenclature. Hybridization of k1 and k2 accessions was previously characterized as an interspecific crosses with low fertility [11, 19]. All 17 k1 x k2 F1, F2 and F2:3 accessions in this study demonstrated low fertility. This is in agreement with a previous report of low fertility of the PI 172996 (acc. 116) x ‘Peri’ F1 hybrid [41]. In this study O. basilicum accession ‘Peri’ is replaced with SB17 (acc. 20) and used as recurrent parent to generate the RU172S BC1 progeny (Fig. 2a). Three RU172S BC1 individuals demonstrated increased fertility relative to the F1, suggesting restoration of reproductive viability may be correlated with increased k1 membership and providing a platform for development of near isogenic lines (NILs). Thus, introgression of traits such as disease resistance from k2 accessions to commercial sweet basil is possible through backcross breeding.

A majority (60%) of single allele loci among k3 accessions was nearly two- and three-fold greater than k1 and k2, respectively. One of two scenarios are likely to explain the predominance of single-allele EST-SSRs among k3 accessions. First, it is possible that a divergent sub-genome is shared among k3 accessions, but does not have adequate homology for transferability of SSR markers derived from O. basilicum EST database. This would suggest a system similar to triplicated Brassica genomes in which B. napus AACC and B. juncea AABB have only the A genomes in common [49]. A second possibility is the complete absence of a sub-genome, which would suggest k3 as a diploid cluster. A diploid genome hypothesis was previously proposed for k3 O. gratissimum and O. tenuiforum accessions [11, 15], which have consistently lower 2C-values [12, 13]. Furthermore, the recently sequenced genome of O. tenuiflorum genotype ‘CIM Ayu’ is described as a diploid (2n = 2× = 16) with a 386 Mbp genome [15], more than ten-fold less than tetraploid O. basilicum based on 2C estimates [12, 13]. Koroch et al. [13] reported a 2C-value for k3.3 accession 160 (PI 652066, O. campechianum) significantly lower (p < 0.001) than k3.1 accession 143 (PI 652059, O. tenuiflorum). Accession 182 (PI 511865) was the most basal accession in this study (Fig. 2b), yet is reported to have a 2C-value comparable to PI 652059 (acc. 143) [13]. Thus, comparison of previously reported nucleic acid content with allelic distribution, genetic distance estimates and cluster analyses in this study suggest a complex Ocimum spp. genome evolution with multiple chromosomal accumulation and/or deletion events.

Three F1 progeny of k3.1 accession 139 ('Spice') hybridized with O. basilicum k1.1 accessions 22 (RUSB_09), 6 ('DiGenova') and 47 (MRI) form a well-supported (0.938) clade with admixed accessions 135 (PI 414201) and 136 (PI 414203) (Fig. 2b). Sterility among these progeny suggest a major reproductive barrier between commercially important O. basilicum k1.1 accessions and highly supported (1.00) k3 clade. Ben-Naim et al. reported F1 sterility among progeny of DM resistant accessions 161 (PI 500945) and 168 (PI 500950) hybridized with O. basilicum accession ‘Peri’ [41]. These accessions are found in the k2.2 sub-cluster suggesting the k1 x k3 F1 sterility barrier extends to this more basal clade (Fig. 2b). Surprising k1 qI among a number of non-hybrid k3 accessions 149-155 (Fig. 2b) suggests the possibility of recently shared ancestry between these clusters. However, sterility among Kivumbisi Lime x SB17 progeny demonstrates high k1.1 qI does not correspond to fertility. Viable F1 progeny could not be obtained from cross-pollination of k1.1 and k3.3 accessions. This is consistent with at least one previous report of attempted O. basilicum x O. tenuiflorum hybridization [47].

Although evidence of varying ploidy levels is a suspected cause of reproductive barriers among wide crosses [41] the exact mechanism remains unclear. Comparative genomic analysis of cultivated and wild Solanum spp. demonstrate seed and pollen infertility can be controlled by a small number of loci with shared evolutionary history [50]. Further investigation is needed to determine the cause of infertility among Ocimum spp.

Distribution of DM resistance and breeding

Forty-three unique sources of genetic resistance to DM are identified from greenhouse screening in this study. These resistant accessions are heavily concentrated in the k3 cluster with 29 from 7 species according to the sources from which they were obtained (Additional file 1). An additional 9 resistant accessions had majority k3 qI membership and UPGMA placement among k3 accessions (Fig. 2b). 116 (PI 172996), 117 (PI 172998) and 119 (PI 296391) were first identified as having little or no disease incidence by Pyne et al. 2013. These accessions demonstrated minimal leaf sporulation in this study (DS ≤ 0.63) and were determined to be in a population (k2) distinct from commercial sweet basil (k1). MRI (acc. 47) represents the only source of DM resistance (DMMRI) identified in the O. basilicum k1 cluster. Recently discovered QTL dm11.1 demonstrated dominant gene action conferred by MRI (acc.47), but detection of additional minor QTL explained additional phenotypic variance and a somewhat complex mechanism for highest levels of resistance [17].

These accessions represent candidates for field confirmation of resistance to P. belbahrii and, ultimately, DM resistance breeding. Ben-Naim et al. found DM response in greenhouse and field experiments to be largely correlated. Response of accessions common across this and previous greenhouse studies [41, 42] is generally consistent with minor differences. Differential disease response of genotypes across studies may be due to a number of confounding effects including environment, inoculum concentration and rating system [51]. Another possibility of greater consequence to disease control is the potential occurrence of pathogen evolution resulting in races exhibiting differential host virulence. Proliferation of races is common among the most economically devastating downy mildews such as Pseudoperonospora cubensis [52], Bremia lactuca [37] and Hyaloperonospora brassicae [53]. Phylogenetic characterization of P. belbahrii isolates is needed to determine the range of genetic diversity and identify possible extant pathogen races.

Candidacy of accessions for DM resistance breeding is contingent upon sexual compatibility and reproductive capacity with commercial sweet basil found in sub-cluster k1.1 (Fig. 2a). DM resistance from k1.1 accession 47 (MRI) is the only documented characterization [17, 54] and introgression of genetic resistance beyond F1 progeny. Partial sterility observed for k1 x k2 crosses appears to be surmountable by backcrossing as demonstrated by the ‘RU172S17’ BC1 accessions 89-92 (Fig. 2a). This represents a potential strategy for introduction of k2 genomic DNA associated with important traits such as intermediate DM resistance (Table 1) and FOB resistance available in many of these accessions. An intermediate DM response (DS = 2.75) for the SB17 x PI 172996 F1 hybrid was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than resistant parent PI 172996 and closer to the mid-parent DS of 2.18 suggesting resistance may be quantitative. The heritability of DM resistance from k2 accessions such as PI 172996 is unclear and requires further investigation.

The k3 cluster represents a rich source of genetic resistance. Furthermore, consistent non-significant differences in disease response for F1 progeny and their resistant parent indicate dominant gene action is widespread among these candidates [41]. Qualitative and, in particular, single dominant gene control of DM is well documented across plant species [37, 55, 56]. HR in O. tenuiflorum accessions 156-159 indicates effector triggered immunity [57], a response distinct from the remaining k3 accessions in which no signs or symptoms were observed. It remains unclear whether these accessions have evolved unique resistance genes, but nonhost resistance is more likely among distant relatives of susceptible k1 accessions. Introgression of nonhost resistance from wild lettuce relatives Lactuca serriola and Lactuca saligna to commercial L. sativa is being used to build durable DM resistance [37, 58]. Further investigation is needed to identify redundancy of resistant genes, especially among closely related accessions.

Conclusions

Results of this study provide a robust characterization of population structure, genetic diversity and response to DM among Ocimum spp. EST-SSRs provide a useful tool for increased resolution of this genus through continued germplasm collection and genotyping. Although evidence is concurrent for allotetraploid and allohexaploid genomes among economically important k1 and k2 clusters, respectively, the highly diverse and DM resistance-rich k3 cluster remains complicated by discrepancies in reports of genome size. Characterization of subgenomes as shared or distinct among allopolyploid species and identification of a diploid progenitor(s) are needed to elucidate genome structure.

As breeding among specialty crops becomes increasingly prevalent, more sophisticated tools will be required. This trend is evidenced in Ocimum spp. by recent development of a first draft genome [15], de novo meta-transcriptomics [59, 60] and genetic/QTL mapping [17]. Determination of major and cryptic population structure as well as phylogenetic classification among DM resistant candidates provides another important resource for accelerated genetic improvement.

Methods

Plant material

A 180-accession panel of Ocimum spp. was selected to provide a genus-wide representation of genetic diversity, while targeting germplasm developed primarily for improved performance in important agronomic traits at Rutgers University (Additional file 1). Eight chilling (“RUCB”) and 7 Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. basilici (FOB) (“RUSB”) tolerant O. basilicum inbred lines were selected. Twenty-nine breeding lines were included from two lineages (“RU4S” and “RUMS”) selected for DM resistance. Eighteen F1 hybrids were developed from hybridization of 9 Ocimum spp. accessions of varying DM response with 4 DM-susceptible O. basilicum inbred lines. All cross-pollinations were performed according to Pyne et al. [54]. Seven F2 selections and a single F2:3 individual were included. Four first-generation backcross lines selected for FOB resistance (“RU172S”) were also included. Remaining accessions were obtained from either commercial seed companies or the USDA-GRIN repository (Aimes, IA), ultimately representing 10 species according to these sources. Finally, two catnip (Nepeta cataria) accessions (CN3 and CR9) were included as outgroup species.

Disease rating (phenotypic evaluation)

Seed from commercial, USDA-GRIN and inbred accessions were planted in Fafard Growing Mix 2 (Sun Gro Horticulture, Agawam, MA) and germinated under intermittent misting. Hybrid and non-flowering accessions (‘Pesto Perpetuo’, ‘GCB’ and ‘Pezou’) were cloned by vegetative cutting from mother plants under intermittent misting. The P. belbahrii isolate collected at the Rutgers Agricultural Research and Extension Center (RAREC) in 2013 and maintained on susceptible check variety ‘DiGenova’ was used in this study. Inoculum was prepared and applied to first true leaf sets according to Pyne et al. [61]. Eight seedlings (individuals) per each accession were inoculated and disease ratings were performed 10 days post inoculation (DPI) corresponding to the interval at which disease severity plateaus under these greenhouse conditions. Individual plants were assigned a disease severity score using an ordered categorical scale in which 0 = no sporulation, 1 = 1-10%, 2 = 11-25%, 3 = 26-50%, 4 = 51-100% [54]. A disease severity score (DS) was assigned to each accession from the average of 8 individuals for two, repeated experiments.

EST-SSR genotyping

Young leaves were harvested from axillary nodes of each accession in this study, frozen and then ground using mortar and pestle. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from ~ 80 mg of ground leaf tissue for all accessions using the E.N.Z.A. SP Plant DNA Kit (Omega BioTek, Norcross, GA).

A set of 240 EST-SSR markers were previously developed and used to genotype the accessions MRI and SB22 [17]. Preliminary experiments identified 20 di-, tri- and tetranucleotide repeat markers demonstrating reliable, unambiguous amplification across replicated PCR evaluations in a diverse subset of Ocimum spp. accessions. Given the putative allopolyploid genome structure of these species, markers were considered to be amplified in shared sub-genomes and, thus, orthologous. Seven of the 20 selected markers were previously mapped to a sweet basil linkage map developed from MRI x SB22 F2 mapping population [17]. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA technologies (Coralville, IA). Multiplexed PCR was performed using conditions and fluorescent dyes (FAM, NED, PET and VIC) previously described [17]. Fragments generated from PCR were separated by capillary electrophoresis using an ABI 3500xL Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Genemapper 4.1 (Applied Biosystems) software was used to determine fragment size for alleles across all accessions and exported for downstream analysis.

Polyploidy is a confounding factor in population genetic studies due to the complication of allelic configuration among genotypes. In allopolyploid accessions of a single ploidy amplification of loci in independent sub-genomes provides a platform for conversion to a diploid SSR genotyping system [48, 62]. Accurate, multi-allelic (codominant) genotype assignment of complex germplasm panels with multiple ploidy levels in the absence of subgenome assignment exceeds current data analysis capabilities. Genotype data in this study was therefore scored as binary (presence = 1; absence/null = 0) as suggested by Honig et al. [63]. SSR markers absent of any alleles (primer site mutation) or having many (> 6) alleles (non-specific primer binding) were considered null and coded ‘0’. Genotypes were coded ‘-1’ in the case of missing data. Polymorphic information content (PIC) was calculated for individual alleles using the formula 2PiQi, where Pi is the frequency of presence and Qi is the frequency of absence for a given allele [63]. The binary genotype matrix for all accessions and SSR markers used in this study can be found in Additional file 5.

Phenotype data analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using R software to determine whether the effect of genotype was significant with respect to the response variable, DS. The agricolae package in R was used to perform DS mean separation using Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test with α = 0.05. All accessions were included in this analysis with the exception of PI 511865, which was found to segregate and, thus, could not be treated as a single genotype.

Population structure analysis

To determine population structure, a nested Bayesian model-based clustering approach described by [64] was implemented with Structure ver 2.3.4 software [44] to infer assignment of individuals to K clusters and sub-clusters. This approach has been effective in identifying important major and cryptic population structure in various plant species including apple [65], cotton [48] and rice [66]. All simulations were performed using the ‘admixture model’ with ‘correlated allele frequencies’. The algorithm was executed with parameters set to a burnin of 100,000 followed by 200,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) repetitions with 10 replicated runs per K. Initial (primary) Structure analysis was performed for K = 1 – 15 using all 180 accessions to determine major delineations in overall population structure. Evanno’s method [67] was employed to provide an estimate of the most likely number of clusters using Structure Harvester software v0.6.94 [68] to determine the natural logarithm probability Pr(X|K) and ad hoc ΔK statistic (mean(|L”(K)|) / sd(L(K)) from membership coefficient (qI) matrices. Following selection of the optimal K for all replicated runs, the FULLSEARCH algorithm of CLUMPP software [69] was used to identify the optimal permuted order of qI matrices with the greatest pairwise similarity. The average of this permutation provided the best qI matrix representation, which was visualized using DISTRUCT software [70].

Determinations of the qI threshold at which to infer cluster assignment vary by study, but range from qI = 0.5 [71] – 0.8 [65]. Inclusion of wide crosses (F1, F2 and BC1) in this study provided a measure of high admixture, which informed the selection of 0.70 as an appropriate qI threshold. Thus, accessions were assigned to the cluster for which qI > 0.70, while those with a maximum qI less than 0.70 were considered admixed. In addition, hybrid (F1, F2, F2:3) and first backcross (BC1) accessions with parentage assigned to two different clusters were considered admixed.

Nested (secondary) Structure analysis was performed separately for non-admixed accessions of each cluster ascertained from the primary analysis. Algorithm parameters were identical to that of the primary analysis but included K = 1-10. Hybrid and backcross accessions were then assigned to sub-clusters by replacing the primary qI with secondary qI determined for each parent. Accessions for which parentage was unknown were excluded from secondary Structure analysis. Assignment to sub-clusters was repeated using the same admixture criteria as in the primary analysis.

AMOVA

The integrity of clusters derived from population structure was further investigated by performing an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) using GenAlEx 6.501 software [72]. A Nei [73] genetic distance matrix was first calculated using the binary genotype matrix previously described for the model-based clustering analyses. Two separate AMOVA were performed to partition within and among population estimated and molecular variance (σ2) components. Statistical significance of pairwise genetic distance among (i) primary and (ii) secondary clustering iterations were used to calculate the pairwise population PhiPT (ΦPT) test statistic, which provides a measure of interpopulation genetic diversity with intra-individual (heterozygosity) variation suppressed. The ΦPT statistic was calculated for all pairwise cluster combinations, which were determined significantly different (p < 0.05) by 999 random permutations of the data.

UPGMA

To investigate genetic relationships among accessions in the full panel, unweighted pair group method using arithmetic average (UPGMA) clustering was performed with Numerical Taxonomy System (NTSYSpc) ver 2.21q software (Exeter Software, Setauket, New York, USA) [46]. Genotype data from outgroup accessions CN3 and CR9 (Nepata cataria) were added to the same binary genotype matrix used for population structure and AMOVA analyses resulting in a total of 182 accessions. A genetic similarity matrix was generated using the Jaccard similarity coefficient method [74] in the NTSYSpc SIMQUAL module. Cluster analysis was then performed by UPGMA in the SAHN module and the output was visualized as a dendrogram with the TREE module. A Mantel test was performed with 999 test permutations using the MXCOMP module to determine goodness of fit between the genetic similarity matrix and the UPGMA dendrogram converted to cophenetic values with the COPH module. Finally, the original binary genotype matrix was resampled 1000 times using the RESAMPLE module and the results were used as input for the CONSENS module to calculate bootstrap values using the majority rule method and a minimum support value of 0.500.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

Association mapping

- AMOVA:

-

Analysis of molecular variance

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BC:

-

Backcross generation

- cDNA:

-

Chloroplast DNA

- cM:

-

CentiMorgan

- DM:

-

Downy mildew

- DMMRI :

-

MRI-conferred downy mildew resistance

- DPI:

-

Days post inoculation

- DS:

-

Disease severity

- EST:

-

Expressed sequence tag (EST)

- FOB:

-

Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. basilica

- gDNA:

-

Genomic DNA

- HR:

-

Hypersensitive response

- HSD:

-

Tukey’s honest significant difference

- ISSR:

-

Inter-simple repeat markers

- MCMC:

-

Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NIL:

-

Near isogenice lines

- NTSYSpc:

-

Numerical Taxonomy System

- PIC:

-

Polymorphism information content

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SSR:

-

Simple sequence repeat

- SSWP :

-

Within population sum of squares

- Tm :

-

Melting temperature

- UPGMA:

-

Unweighted pair group method using arithmetic average

- USDA-GRIN:

-

United States Department of Agriculture National Genetic Resources Program

References

Paton A, Harley MR, Harley MM. Ocimum: an overview of classification and relationships. In: Hiltunen R, Holm Y, editors. Basil: the genus Ocimum. Amersterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. p. 1–38.

Vieira RF, Goldsbrough P, Simon JE. Genetic diversity of basil (Ocimum spp.) based on RAPD markers. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2003;128:94–9.

Paton AJ, Springate D, Suddee S, Otieno D, Grayer RJ, Harley MM, et al. Phylogeny and evolution of basils and allies (Ocimeae, Labiatae) based on three plastid DNA regions. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;31:277–99.

Simon JE, Quinn J, Murray JG. Basil: a source of essential oils. In: Janick J, Simon JE, editors. Advances in new crops. Portland: Timber Press; 1990. p. 484–9. Available: https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/proceedings1999/pdf/v4-499.pdf.

Putievsky E, Galambosi B. Production systems of sweet basil. In: Hiltunen R, Holm Y, editors. Basil: the genus Ocimum. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. p. 39–61.

Chaimovitsh D, Dudai N, Putievesky E, Ashri A. Inheritance of resistance to fusarium wilt in sweet basil. Phytopathology. 2006;90:58–60.

Ribeiro P, Simon JE. Breeding sweet basil for chilling tolerance: ASHS; 2007. p. 302–5.

Morales MR, Simon JE. “Sweet Dani”: a new culinary and ornamental basil. Hortscience. 1997;1:148–9.

Nation RG, Janick J, Simon JE. Estimation of outcrossing in basil. Hortic Sci. 1992;27:1221–2.

Khosla MK, Tawi J, Group S. Karyomorphological studies in genus Ocimum. Cytologia (Tokyo). 1985;50:253–63.

Pushpangandan P, Sobti SN. Cytogentical studies in the genus Ocimum. I. Origin of O. americanum, cytotaxonomical and experimental proof. Cytologia. 1982;47:575–83.

Carović-Stanko K, Liber Z, Besendorfer V, Javornik B, Bohanec B, Kolak I, et al. Genetic relations among basil taxa (Ocimum L.) based on molecular markers, nuclear DNA content, and chromosome number. Plant Syst Evol. 2010;285:13–22.

Koroch AR, Wang W, Michael TP, Dudai N, Simon JE, Belanger FC. Estimation of nuclear DNA content of cultivated Ocimum species by using flow cytometry. Isr J Plant Sci. 2010;58:183–9.

Escudero M, Martín-Bravo S, Mayrose I, Fernández-Mazuecos M, Fiz-Palacios O, Hipp AL, et al. Karyotypic changes through dysploidy persist longer over evolutionary time than polyploid changes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85266. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085266.

Rastogi S, Kalra A, Gupta V, Khan F, Lal RK, Tripathi AK, et al. Unravelling the genome of holy basil: an “incomparable” “elixir of life” of traditional Indian medicine. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:413. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1640-z.

Ramsey J, Schemske DW. Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of Polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1998;29:467–501.

Pyne R, Honig J, Vaiciunas J, Koroch AR, Wyenandt CA, Bonos SA, et al. A first linkage map and downy mildew resistance QTL discovery for sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) facilitated by double digestion restriction site associated DNA sequencing (ddRADseq). PLoS One. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1371/journalpone.0184319.

Carović-Stanko K, Liber Z, Politeo O, Strikić F, Kolak I, Milos M, et al. Molecular and chemical characterization of the most widespread Ocimum species. Plant Syst Evol. 2011;294:253–62.

Paton AJ, Putievesky E. Taxonomic problems and cytotaxonomic relationships between and within varieties of Ocimum basilicum and related species (Labiateae). Kew Bull. 1996;51:509–24.

Suddee S, Paton AJ, Parnell JAN. Taxonomic revision of tribe Ocimeae Dumort. (Lamiaceae) in continental South East Asia III. Ociminae. Kew Bull. 2005;60:3–75.

Carović-Stanko K, Šalinović A, Grdǐa M, Liber Z, Kolak I, Satovic Z. Efficiency of morphological trait descriptors in discrimination of Ocimum basilicum L. accessions. Plant Biosyst. 2011;145:298–305.

Grayer RJ, Kite GC, Goldstone FJ, Bryan SE, Paton A, Putievsky E. Infraspecific taxonomy and essential oil chemotypes in sweet basil, Ocimum basilicum. Phytochemistry. 1996;43:1033–9.

Vieira RF, Simon JE. Chemical characterization of basil (Ocimum spp.) based on volatile oils. Flavour Fragr J. 2006;21:214–21.

Paton A, Harley MR, Harley MM. Ocimum: an overview of classification and relationships. In: Hiltunen R, Holm Y, editors. Basil: the genus Ocimum. Amsterdam: Hardwood Academic; 1996. p. 1–38.

Simpson MG. Plant systematics. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2010.

Fehr WR. Principles of cultivar development. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company; 1987.

Labra M, Miele M, Ledda B, Grassi F, Mazzei M, Sala F. Morphological characterization, essential oil composition and DNA genotyping of Ocimum basilicum L. cultivars. Plant Sci. 2004;167:725–31.

Vieira RF, Grayer RJ, Paton A, Simon JE. Genetic diversity of Ocimum gratissimum L. based on volatile oil constituents, flavonoids and RAPD markers. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2001;29:287–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-1978(00)00062-4.

Kumar A, Mishra P, Baskaran K, Shukla AK, Shasany AK, Sundaresan V. Higher efficiency of ISSR markers over plastid psbA-trnH region in resolving taxonomical status of genus Ocimum L. Ecol Evol. 2016;6:7671–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2483.

Kalia RK, Rai MK, Kalia S, Singh R, Dhawan AK. Microsatellite markers: an overview of the recent progress in plants. Euphytica. 2011;177:309–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-010-0286-9.

Ramchiary N, Nguyen VD, Li X, Hong CP, Dhandapani V, Choi SR, et al. Genic microsatellite markers in brassica rapa: development, characterization, mapping, and their utility in other cultivated and wild brassica relatives. DNA Res. 2011;18:305–20.

Li H, Younas M, Wang X, Li X, Chen L, Zhao B, et al. Development of a core set of single-locus SSR markers for allotetraploid rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:937–47.

Belbahri L, Calmin G, Pawlowski J, Lefort F. Phylogenetic analysis and real time PCR detection of a presumbably undescribed Peronospora species on sweet basil and sage. Mycol Res. 2005;109:1276–87.

Wyenandt CA, Simon JE, Pyne RM, Homa K, McGrath MT, Zhang S, et al. Basil downy mildew (Peronospora belbahrii): discoveries and challenges relative to its control. Phytopathology. 2015;105:885–94. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-02-15-0032-FI.

Cohen Y, Van den Langenberg KM, Wehner TC, Ojiambo PS, Hausbeck M, Quesada-Ocampo LM, et al. Resurgence of Pseudoperonospora cubensis: the causal agent of cucurbit downy mildew. Phytopathology. 2015;105:998–1012.

Call AD, Criswell AD, Wehner TC, Ando K, Grumet R. Resistance of cucumber cultivars to a new strain of cucurbit downy mildew. Hortscience. 2012;47:171–8.

Parra L, Maisonneuve B, Lebeda A, Schut J, Christopoulou M, Jeuken M, et al. Rationalization of genes for resistance to Bremia lactucae in lettuce. Euphytica. 2016;210:309–26.

Cohen Y, Vaknin M, Ben-Naim Y, Rubin AE, Galperin M, Silverman D, et al. First report of the occurrence and resistance to Mefenoxam of Peronospora belbahrii, causal agent of downy mildew of basil (Ocimum basilicum) in Israel. Plant Dis Sci Soc. 2013;97:692.

Pintore I, Gilardi G, Gullino ML, Garibaldi A. Detection of mefenoxam-resistant strains of Peronospora belbahrii, the causal agent of basil downy mildew, transmitted through infected seeds. Phytoparasitica. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-016-0538-x.

Collina M, Merighi M, Turan C, Pirondi A, Minuto G, Brunelli A. First report of resistance of Peronospora belbahrii, causal agent of downy mildew of basil, to Mefenoxam in Italy. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1787.

Ben-Naim Y, Falach L, Cohen Y. Resistance against basil downy mildew in Ocimum species. Phytopathology. 2015;105:778–85.

Djalali Farahani-Kofoet R, Romer P, Grosch R. Selecting basil genotypes with resistance against downy mildew. Sci Hortic. 2014;179:248–55.

Wyenandt CA, Simon JE, McGrath MT, Ward DL. Susceptibility of basil cultivars and breeding lines to downy mildew (Peronospora belbahrii). Hortscience. 2010;45:1416–9.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Zhu C, Gore M, Buckler ES, Yu J. Status and prospects of association mapping in plants. Plant Genome. 2008;1:5–20.

Rohlf FJ. NTSYSpc: numerical taxonomy system. Setauket: Exeter Publishing, Ltd.; 2008.

Putievesky E, Paton A, Lewinsohn E, Ravid U, Haimovich D, Katzir I, et al. Crossability and relationship between Ocimum basilicum L. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 1999;6:11–24.

Zhao Y, Wang H, Chen W, Li Y. Genetic structure, linkage disequilibrium and association mapping of verticillium wilt resistance in elite cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) germplasm population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86308. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086308.

Cheng F, Wu J, Wang X. Genome triplication drove the diversification of Brassica plants. Horticultural Research. 2014;1:14024. https://doi.org/10.1038/hortres.2014.24.

Moyle LC, Nakazato T. Comparative genetics of hybrid incompatibility: sterility in two Solanum species crosses. Genetics. 2008;1453:1437–53.

Agrios GN. Plant pathology. 5th ed. Burlington: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005.

Ojiambo PS, Gent DH, Quesada-Ocampo LM, Hausbeck MK, Holmes GJ. Epidemiology and population biology of Pseudoperonospora cubensis: a model system for Management of Downy Mildews. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2015;53:223–46.

Vicente JG, Gunn ND, Bailey L, Pink DAC, Holub EB. Genetics of resistance to downy mildew in Brassica oleracea and breeding towards durable disease control for UK vegetable production. Plant Pathol. 2012;61:600–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2011.02539.x.

Pyne RM, Koroch AR, Wyenandt CA, Simon JE. Inheritance of resistance to downy mildew in sweet basil. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2015;140:396–403.

Irish BM, Correll JC, Feng C, Bentley T, de Los Reyes BG. Characterization of a resistance locus (Pfs-1) to the spinach downy mildew pathogen (Peronospora farinosa f. sp. spinaciae) and development of a molecular marker linked to Pfs-1. Phytopathology. 2008;98:894–900.

Epinat C, Pitrat M. Inheritance of resistance of three lines of muskmelon (Cucumis melo) to downy mildew (Pseudoperonospora cubensis). Charleston: Proc Cucurbitaceae: Evaluation and Enhancement of Cucurbit Germplasm; 1989. p. 133–5.

Jones JDG, Dangl L. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–9.

Zhang NW, Lindhout P, Niks RE, Jeuken MJW. Genetic dissection of Lactuca saligna nonhost resistance to downy mildew at various lettuce developmental stages. Plant Pathol. 2009;58:923–32.

Guo L, Allen KS, Deiulio GA, Zhang Y, Madeiras AM, Wick RL, et al. A de-novo-assembly-based data analysis pipeline for plant obligate parasite metatranscriptomic studies. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:925. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2016.00925.

Rastogi S, Meena S, Bhattacharya A, Ghosh S, Shukla RK, Sangwan NS, et al. De novo sequencing and comparative analysis of holy and sweet basil transcriptomes. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:588. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-588.

Pyne RM, Koroch AR, Wyenandt CA, Simon JE. A rapid screening approach to identify resistance to basil downy mildew (Peronospora belbahrii). Hortscience. 2014;49:1041–5.

van Dijk T, Noordijk Y, Dubos T, Bink MC, Meulenbroek BJ, Visser RG, et al. Microsatellite allele dose and configuration establishment (MADCE): an integrated approach for genetic studies in allopolyploids. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-12-25.

Honig JA, Kubik C, Averello V, Vaiciunas J, Meyer WA, Bonos SA. Classification of bentgrass (Agrostis) cultivars and accessions based on microsatellite (SSR) markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2016;63:1139–60.

Vähä JP, Erkinaro J, Niemelä E, Primmer CR. Life-history and habitat features influence the within-river genetic structure of Atlantic salmon. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:2638–54.

Urrestarazu J, Denancé C, Ravon E, Guyader A, Guisnel R, Feugey L, et al. Analysis of the genetic diversity and structure across a wide range of germplasm reveals prominent gene flow in apple at the European level. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-016-0818-0.

Nachimuthu VV, Muthurajan R, Duraialaguraja S, Sivakami R, Pandian BA, Ponniah G, et al. Analysis of population structure and genetic diversity in rice germplasm using SSR markers: an initiative towards association mapping of agronomic traits in Oryza Sativa. Rice (N Y). 2015;8:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-015-0062-5.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2611–20.

Earl DA, Bridgett M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012;4:359–61

Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA. CLUMPP: a cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1801–6.

Rosenberg NA. DISTRUCT: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol Ecol Resour. 2004;4:137–8.

Taranto F, D’Agostino N, Greco B, Cardi T, Tripodi P. Genome-wide SNP discovery and population structure analysis in pepper (Capsicum annuum) using genotyping by sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:943.

Peakall R, Smouse PE. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research — an update. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2537–9.

Nei M. Genetic distance between populations. Am Soc Nat. 2010;106:283–92.

Jaccard P. Nouvelles recherches Sur la distribution florale. Bull la Soc Vaudoise des Sci Nat. 1908;44:223–70.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Todd Wehner (North Carolina State University) and Dr. Stacy Bonos (Rutgers University) for their review and suggestions with regard to this manuscript. We thank the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station (NJAES) and the New Use Agriculture and Natural Plant Products Program (NUANNP) for their expertise and support of this research.

Funding

Funds in support of this research were provided from multiple sources. A United States United Department of Agriculture (USDA) Special Crops Research Initiative Award No. 2011-51181-30646 funded a graduate assistantship/doctoral degree for RMP. This USDA-SCRI grant in combination with a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Award No. 2016-68004-24931 provided funds for acquisition of commercial plant varieties, greenhouse space, DNA extractions and genotyping work. A Binational Agricultural Research & Development (BARD) Award No. US-4947-16R and NIFA HATCH projects NJAES 12131 and 1005685 provided additional funding for genotyping work and greenhouse facilities, respectively.

Availability of data and materials

A table of all genotypes and SSR allele calls used for statistical analysis in this study is submitted as Additional file 5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design of experimentation was performed by RMP, JES and CAW. CAW provided expertise in downy mildew screening including inoculation procedures and plant response phenotyping. RMP performed DNA extraction, genotyping and greenhouse downy mildew response phenotyping. JV coordinated laboratory work and provided expertise in SSR allele calling to ensure accurate DNA fragment length data. RMP performed data analyses with supervision JH. Interpretation of data was performed by RMP and JH. CAW, JH and JES supervised the writing and revision of this manuscript. JES and JH coordinated resources and personnel necessary to complete this research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Description of 180-accession panel of Ocimum spp., cluster membership and response to downy mildew (Peronospora belbahrii) reported as disease severity. (PDF 115 kb)

Additional file 2:

Primer sequences and melting temperatures (Tm) for the EST-SSRs used in this study. (PDF 52 kb)

Additional file 3:

Structure Harvester output for primary model-based clustering using Structure ver 2.3.4 software. Plot of ΔK (left) and LnP(D) (right) for K = 1 – 15. (PDF 126 kb)

Additional file 4:

Structure Harvester output for secondary (nested) model-based clustering using Structure ver 2.3.4 software. Plots of ΔK (left) and LnP(D) (right) for K = 1 – 10. Three nested analyses shown for k1 (top), k2 (middle) and k3 (bottom) primary clusters. (PDF 215 kb)

Additional file 5:

Genotype data. Binary matrix of accessions (rows) and alleles (columns). (XLSX 186 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pyne, R.M., Honig, J.A., Vaiciunas, J. et al. Population structure, genetic diversity and downy mildew resistance among Ocimum species germplasm. BMC Plant Biol 18, 69 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1284-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1284-7