Abstract

Background

Avian colibacillosis is an infectious bacterial disease caused by avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). APEC causes a wide variety of intestinal and extraintestinal infections, including InPEC and ExPEC, which result in enormous losses in the poultry industry. In this study, we investigated the prevalence of InPEC and ExPEC in Central China, and the isolates were characterized using molecular approaches and tested for virulence factors and antibiotic resistance.

Results

A total of 200 chicken-derived E. coli isolates were collected for study from 2019 and 2020. The prevalence of B2 and D phylogenic groups in the 200 chicken-derived E. coli was verified by triplex PCR, which accounted for 50.53% (48/95) and 9.52% (10/105) in ExPEC and InPEC, respectively. Additionally, multilocus sequence typing method was used to examine the genetic diversity of these E. coli isolates, which showed that the dominant STs of ExPEC included ST117 (n = 10, 20.83%), ST297 (n = 5, 10.42%), ST93 (n = 4, 8.33%), ST1426 (n = 4, 8.33%) and ST10 (n = 3, 6.25%), while the dominant ST of InPEC was ST117 (n = 2, 20%). Furthermore, antimicrobial susceptibility tests of 16 antibiotics for those strains were conducted. The result showed that more than 60% of the ExPEC and InPEC were resistant to streptomycin and nalidixic acid. Among these streptomycin resistant isolates (n = 49), 99.76% harbored aminoglycoside resistance gene strA, and 63.27% harbored strB. Among these nalidixic acid resistant isolates (n = 38), 94.74% harbored a S83L mutation in gyrA, and 44.74% harbored a D87N mutation in gyrA. Moreover, the prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) in the isolates of ExPEC and InPEC was 31.25% (15/48) and 20% (2/10), respectively. Alarmingly, 8.33% (4/48) of the ExPEC and 20% (2/10) of the InPEC were extensively drug-resistant (XDR). Finally, the presence of 13 virulence-associated genes was checked in these isolates, which over 95% of the ExPEC and InPEC strains harbored irp2, feoB, fimH, ompT, ompA. 10.42% of the ExPEC and 10% of the InPEC were positive for kpsM. Only ExPEC isolates carried ibeA gene, and the rate was 4.17%. All tested strains were negative to LT and cnf genes. The carrying rate of iss and iutA were significantly different between the InPEC and ExPEC isolates (P < 0.01).

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the highly pathogenic groups of InPEC and ExPEC in Central China. We find that 50.53% (48/95) of the ExPEC belong to the D/B2 phylogenic group. The emergence of XDR and MDR strains and potential virulence genes may indicate the complicated treatment of the infections caused by APEC. This study will improve our understanding of the prevalence and pathogenicity of APEC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) is responsible for a variety of extra-intestinal pathogenic effects in poultry. The most common lesions observed on gross postmortem of avians with systemic colibacillosis include airsacculitis, pericarditis, and perihepatitis [1, 2]. Most E. coli are commensal bacteria colonizing in the gut. However, pathogenic E. coli can cause various infections in the intestinal system and the bloodstream. Based on whether the disease syndrome is intra- or extra-intestinal, pathogenic E. coli can be classified into InPEC and ExPEC [3]. Recent studies have reported significant differences in the evolutionary tree, drug resistance, sequence types (ST) and virulence genes of E. coli isolates obtained from humans and poultry in China and elsewhere, but there are very few reports regarding InPEC and ExPEC in Central China.

The phylogenetic classifications of InPEC and ExPEC were significantly different. Najafi et al. showed that commensal E. coli that survive within the intestinal system mainly belong to the A/B1 group, while those in the highly pathogenic ExPEC are generally in the B2/D group [4]. A similar study with 994 avian isolates conducted by Johnson et al. showed that all of which were highly pathogenic and capable of causing colisepticemia [5]. Sen et al. [6] analyzed samples from crow feces and water in their wetland habitat. They showed that crows were the carriers of ExPEC and APEC-like strains and the majority of ExPEC isolates were associated with E. coli phylogenetic groups B2 and D. Pathogenic E. coli found in humans and poultry carcasses showed similar virulence and resistance [7].

A variety of APEC virulence factors determine their pathogenicity. The virulence factor genes iutA and iroN (iron metabolism), iss (increased serum survival), hlyF (hemolysis), and ompT (surface exclusion and serum survival) could be present on large plasmids, a defining and necessary trait for APEC virulence [3]. In addition to these plasmid associated genes, APEC isolates were also characterized by the possession of certain chromosomally encoded virulence genes including fyuA (yersiniabactin receptor), pap operon genes (papA, papC, papEF, and papG that encode parts of the P pilus), and ibeA (pathogenicity island markers) [8, 9]. Stromberg et al. [10] showed that the distribution of papA, papC, papEF, papG2, papG3, kpsM II, and tsh was significantly different (P < 0.001) between ExPEC (n = 40) and non-ExPEC (n = 37) samples. Additionally, they found that some E. coli isolates from feces of healthy chicken had ExPEC virulence-associated genes, which could cause ExPEC-associated illness in animal models. Their study showed that the E. coli isolates containing ExPEC-associated genes might contribute to the chicken-to-chicken ExPEC transmission through pecking or inhalation of contaminated fecal dust. These isolates may ultimately result in severe poultry disease or death. Not only causing disease in chicken, but a recent study also showed that the prevalence of ibeA indicated a closer relationship between APEC and newborn meningitic (NMEC) strains, which has a zoonotic potential and presents a significant health risk to humans [11].

MLST (Multilocus sequence typing) data from previous studies have shown that ST10, ST48, ST95, and ST117 predominate among the E. coli STs found in poultry [12]. The sequence types of the ExPEC isolates belonging to the B2 phylogenetic group were analyzed by MLST, showing the most prevalent genotypes were ST131, ST95, ST14, ST10, ST69, ST1722, ST141, ST88, ST80, and ST99 8[13]. Genotypic analysis of E. coli isolates from pigs with diarrhea in China revealed that the most prevalent genotypes were ST10 and ST48, followed by ST29, ST744, ST101, ST4214, and ST61 7[14]. The most prominent genotype was ST117, ST2847 and ST48 in APEC [15].

Drug-resistant APEC strains can contaminate the food supply from farm to fork through eggs, meat, and other commodities and thus pose a severe threat to consumer health [16]. Inappropriate selection and abuse of antibiotics in the poultry industry may have contributed to drug resistance in APEC. The E. coli isolates considered resistant using the cut-offs provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), while the intrinsic resistance needs to be addressed by multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), pan drug-resistant PDR [17]. Hirakata showed China faced the highest rate of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) among all Asian countriers [18]. China utilizes the largest quantity of antibiotics worldwide. Almost 30% of drugs are sold to China. This proportion of antibiotic usage is about 20% higher than the developed countries [19]. Many researchers reported the MDR of cephalosporins, quinolones, aminoglycosides, and penicillin among the E. coli strains isolated from animals and humans, which reflected the extensive and heavy use of these antibiotics in Western and Eastern China [20,21,22].

Therefore, it is important to study the relationships between the genetic evolution of InPEC and ExPEC isolates and their pathogenicity and drug resistance to improve our understanding of the prevalence and pathogenicity of APEC.

Results

Classifying of phylogenetic groups of E. coli isolates

A phylogenetic group analysis of 200 E. coli from chicken revealed that most of the E. coli strains isolated belonged to group A (n = 92, 46%), followed by groups B1 (n = 50, 25%), B2 (n = 18, 9%), and D (n = 40, 20%), which suggested that 58 isolates (B2 and D) were APEC. A total of 58 APEC were divided into 48 ExPEC from sick and diseased chickens, included liver (n = 26), brain (n = 9), heart (n = 5), lung (n = 3), eye (n = 1), breast (n = 1) and stomach (n = 1) in Xiannin, Jiangxia, Xiangyang, Shishou, and Yichang cities, and 10 InPEC from diseased broiler chickens: feces (n = 2), intestine (n = 8) in Xiannin, Jiangxia, Tianmen, Xinzhou, Xiangyang cities. The determination of E. coli phylogenetic groups showed that the majority of the 95 isolates from extra-intestinal tissues belonged to phylogenetic group D (n = 34, 35.8%), followed by groups A (n = 26, 27.4%), B1 (n = 21, 22.1%), and B2 (n = 14, 14.7%), while the majority of the 105 isolates from feces and intestines belonged to phylogenetic group A (n = 66, 62.9%), followed by groups B1 (n = 29, 27.6%), D (n = 6, 5.7%), and B2 (n = 4, 3.8%) (Fig. 1) (Table 1). These results showed that the E. coli from feces and intestines mostly belong to group A, while the E. coli from extra-intestinal tissues mostly belong to group D. The distribution of occurrence of groups A, B2, and D were significantly different between E. coli isolates from extra-intestinal (27.4, 14.7, and 35.8%, respectively) and intestinal tissues (62.9, 3.8, and 5.7%, respectively) in our study (P < 0.01).

The certification of phylogenetic groups of partial E. coli isolates by PCR amplification. M. 2000 bp DNA ladder; B2 phylogenetic group (chuA+ yjaA+ tspE4.C2−), lane 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 28; D phylogenetic group (chuA+ yjaA− tspE4.C2−), Lane 6, 7, 9, 27, 29, 31; B1 phylogenetic group (tspE4.C2+ chuA− yjaA−), Lane 5, 8, 12, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 30; A phylogenetic group (chuA− yjaA− TspE4.C2−), Lane 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39; N. negative control, Lane 40

MLST of genetic diversity of InPEC and ExPEC

The genetic diversity of all isolates belonged to high phylogenetic groups (58 isolates, groups B2 and D), including 48 ExPEC and 10 InPEC, was analyzed by MLST. The results showed that 58 strains of InPEC and ExPEC contained 29 STs (Fig. 2). The dominant phylogenetic genotype group in InPEC isolates was ST117 (20%), and the percent of other STs was all 10%, included ST4456, ST354, ST2736, ST115, ST10, ST2169, and ST3190. The ExPEC isolates were divided into 22 STs. The dominant genotypes were ST117 (20.83%), ST297 (10.42%), ST93 (8.33%), ST1426 (8.33%), ST10 (6.25%), ST1485 (4.17%), and ST70 (4.17%), while the single occurrence of 15 other STs was identified, including ST162, ST1258, ST13, ST4063, ST1551, ST2220, ST2055, ST6789, ST746, ST2207, ST5066, ST106, ST2732, ST2113, and ST6862, indicating the high genetic diversity of ExPEC (Fig. 2). ST117 had the widest distribution in InPEC and ExPEC isolates.

Distribution of virulence genes in InPEC and ExPEC

The distribution of 13 virulence genes in 58 strains of InPEC and ExPEC has been examined in this study. As shown in Table 2, cnf and LT were not found in all isolates, while the other 11 virulence-associated genes, including irp2, ompA, feoB, ompT, and fimH, were found in most of the InPEC and ExPEC isolates. Additionally, the presence of kpsM was low in InPEC (10%) and ExPEC (10.42%). ibeA was not detected in InPEC isolates and was found in only two isolates of ExPEC. The presence of iroD and hlyA was 50–70% in both InPEC and ExPEC isolates, while the distribution of iss and iutA was significantly difference between InPEC and ExPEC isolates (P < 0.01).

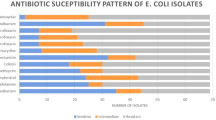

Antimicrobial resistant patterns in InPEC and ExPEC

The differences in the distribution of antimicrobial resistant patterns between 58 strains of InPEC and ExPEC in our study were tested against 16 types of antimicrobial agents. Most of the InPEC and ExPEC isolates were resistant to nalidixic acid (87.5% in ExPEC and 60% in InPEC), streptomycin (87.5% in ExPEC and 70% in InPEC), gentamicin (18.75% in ExPEC and 60% in InPEC), and kanamycin (33.33% in ExPEC and 50% in InPEC). A few of the InPEC and ExPEC showing the lowest resistance rate, which were cefoxitin (2.1% in ExPEC and 30% in InPEC), cefepinme (8.33% in ExPEC and 10% in InPEC), and amikacin (4.17% in ExPEC and 0% in InPEC) (Table 3). Notably, 29.31% (17/58) of the isolates were resistant to at least 3 different types of antibiotics and classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. The 17 isolates presented 11 different types of antibiotic resistance patterns. Additionally, 10.34% (6/58) of the isolates remain susceptible to only one or two antimicrobial agents, categorized as XDR, including two types of antibiotic resistance patterns (Table 4).

Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes

Among the 58 strains of InPEC and ExPEC, aminoglycoside resistant genes strA, strB, and aadA were found in 82.76, 53.45, and 1.72% of these isolates respectively, and all of the streptomycin resistant isolates (n = 49) contained one or more of these resistance genes. Of the β-lactamases resistant genes, CTX-M was the most prevalent gene (56.90%), followed by SHV (41.38%), OXA (5.17%) and TEM (1.72%). The S83L mutation and D87N mutation in gyrA, which could cause quinolones/fluoroquinolones resistance, were found in 62.06 and 29.31% of our InPEC and ExPEC isolates. Among these streptomycin nalidixic acid resistant isolates(n = 38), 94.74% contained S83L mutation in gyrA (Table 3, Supplement Table 1).

Discussion

Poultry and their products are commonly consumed by humans, but little detailed information is available regarding the InPECs and ExPECs isolated from poultry in Central China. In our study, we found that 29% of the 200 clinical samples belonged to high phylogenetic groups of InPEC and ExPECs, posing a severe threat to consumer health. ExPECs cause multi-system mixed infections in avians, including myocarditis, septicemia, perihepatic and balloon inflammations. Most of the ExPECs belonged to groups B2 and D, especially the highly pathogenic strains in group B2, while the symbiotic E. coli and InPEC were mainly in groups A and B1. Although many investigators have shown that APEC is a type of ExPEC, this study is the first to distinguish the relationship between ExPEC and InPEC in groups B2 and D of APEC. The distribution of phylogenetic groups showed that the majority of the 95 extra-intestinal E. coli belonged to phylogenetic group D (35.8%), followed by groups A (27.4%), B1 (22.1%), and B2 (14.7%), and the majority of the 105 intestinal E. coli belonged to phylogenetic group A (62.9%), followed by groups B1 (27.6%), D (5.7%), and B2 (3.8%), the results that are consistent with Amani F [17]. Hussain et al. [23] and Huja et al. [18] analyzed the entire genome sequences of 28 E. coli isolates from 12 broiler chickens (ten from the cecum and two from meat), 11 free-range chickens (six from the cecum and five from meat), and five human ExPEC isolates. The results showed that E. coli from the free-range chicken belonged to group B1, and the human ExPEC isolates and two isolates of E. coli from broiler meat belonged to groups B2 and D, suggesting that phylogroups B2 and D represent significant potential zoonotic factors in ExPEC.

Potential virulence properties include adhesion and invasion of epithelial cells, secretion of iron, serum resistance, and the formation of toxins. To better understand the virulence potential of E. coli isolates, we characterized 13 virulence-associated genes in five types of virulence functions. Iron chelation, which captures trivalent iron (Fe3+) from ferritin and transferrin, plays an essential role in ExPEC virulence. Evaluation of E. coli isolates from healthy chickens, to determine their potential risk to poultry and human health, found the risk genes irp2, feoB, and iutA in more than 89% of the strains isolated, and significant differences in the occurrence of iutA between InPEC and ExPEC (P < 0.01). APEC strains could transmit from avian to humans by improperly prepared poultry meat and direct contact with avians and their feces. In addition, the APEC strains may constitute a reservoir of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pose a potential risk to human health [24, 25]. Amani et al. examined the distribution of irp2 in 45 InPEC and 84 ExPEC isolates from ostriches [26]. They found that 4.4% of the ExPEC isolates contained the irp2 gene compared with 27.9% in InPEC (P < 0.01), while 22.2% of InPEC isolates had the iss gene compared with 25% in ExPEC isolates. Huja et al. showed that the iss gene was conserved in all the E. coli septicemic strains and demanded for septicemia [27]. They also reported that feoB existed in all 48 E. coli isolates, and that 59.3% of ExPEC contained the irp2 gene compared with 27.9% in InPEC isolates (P < 0.01). In the Sistan region of Iran, marker genes of iss and irp2 genes were used to differentiate InPEC and ExPEC strains to improve colibacillosis control measurements [28]. In our study, over 90% of InPEC and ExPEC strains contained irp2 and feoB, and 70.8% of ExPEC isolates contained the iss gene compared with 20% of InPEC isolates (P < 0.01). The deletion of kpsM in E. coli decreased its virulence in pigs and reduced its adhesion, phagocytosis, and serum bactericidal survival [29]. The loss of kpsM decreased the pathology scores in the ileum and ceca of mice [30]. In our study, 4.2% of ExPEC strains contained ibeA compared with 0% in InPEC, and 10.4% of ExPEC had the kpsM gene compared with 10% in InPEC, which are in partial agreement with the studies mentioned above.

Phylogenic groups of B2 and D from ExPEC is relation to ST lineages are common worldwide. The most prevalent lineages of ExPEC in the UK are ST131/B2, ST127/B2, ST95/B2, ST73/B2, and ST69/D. The most widespread lineages of InPEC in Hunan Province were ST95 and ST131 [31]. ST117 can mediate the expression of the resistance genes, such as vanB, foasA, and CTX-M, and is related to serotypes such as O111 and O78 in Enterococcus faecium [32,33,34,35]. Mora et al. studied a human septicemic O111:H4-D-ST117 ExPEC strain in 2000 and 200 9[36]. Their study demonstrated the slow evolution based on virulence-gene differences and macrorestriction profiles and suggested ST117 as a candidate for the development of a future vaccine against avian colibacillosis. In our study, the majority of MLSTs of ExPEC were ST117, ST10 and ST70, and the major MLSTs of InPEC were ST117, ST4456, ST354, ST2736, ST115, ST10, ST2169, and ST3190. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the phylogenic groups of B2 and D of InPEC and ExPEC in Central China. Fourteen different sequence types were identified, with ST117 (16%), ST2847 (10.7%), and ST48 (5.3%) being the most prevalent. ST117 can cause colibacillosis and is a highly pathogenic group whose horizontal transmission poses potential threats to human and bird health.

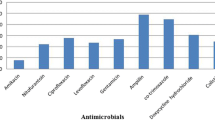

Antibiotic-resistant strains of E. coli have been reported to cause more severe disease in humans, and the emergency of multidrug-resistant strains increases the threat to public safety. Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides and β-lactams are frequently used as therapeutic drugs in the treatment to severe cases. High fluoroquinolone and tetracycline-resistance rates have also been reported in other studies in China and other countries. The genomic landscape of 75 APEC isolates in Pakistan predicted that the percentage of the resistance genes against aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and beta-lactams was 89.33, 89.3, 89.3 and 88%, respectively [15]. Genomic analysis of APEC isolates from Central European countries revealed the predominant multi-antibiotic resistance genes conferring resistance against beta-lactams (28.1%), tetracyclines (37.5%) and sulfonamides (25%). Seventy-nine APEC isolates showed high resistance to ampicillin (83.5%), nalidixic acid (65.8%), tetracycline (64.6%), cephalothin (46.8%), and ciprofloxacin (46.8%) [37]. All of the 116 APEC isolated in Eastern China showed high resistance to ampicillin (100%), tetracycline (100%), nalidixic acid (89.62%), chloramphenicol (83.96%), and kanamycin (80.19%). Most of the InPEC and ExPEC isolates in our study in Central China were resistant to KF (90% in ExPEC and 100% in InPEC), cefotaxime (90% in both ExPEC and InPEC), cefuroxime (81% in ExPEC and 100% in InPEC), and kanamycin (69% in ExPEC and 70% in InPEC). E. coli isolated from frozen chicken meat showed resistance rates of 95.8, 90.4, and 76.7% against cefepime, cefoxitin, and cefotaxime, respectively [38], while the rates to cefotaxime in ExPEC and InPEC were 25 and 30% in our study. The resistance rate to aminoglycosides was quite low in our study (gentamicin, 18.75% in ExPEC and 60% in InPEC; spectinomycin, 12.5% in ExPEC and 20% in InPEC; and amikacin, 4.17% in ExPEC and 0% in InPEC). This result is in disagreement with other authors who have reported higher levels of resistance [39]. Notably, the MDR rate is 80.7% of the isolates from healthy waterfowls in Esatern China [40], whereas the MDR rate is 29.31%, and XDR rate is 10.34% in our study. MDR patterns were more diverse in ExPEC isolates compared with InPEC isolates. Pan et al. [41] characterized a multidrug-resistant region in an F33: A-: B-plasmid carrying blaTEM-1, blaCTX-M-65, rmtB, and fosA3 in an isolate from an avian E. coli strain of ST117. A draft genome sequence of a CTX-M-8, CTX-M-55, and FosA3 co-producing E. coli ST117-B2 was isolated from a human symptomatic carrier [33].

Then, we analyzed the relationships between antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and resistance genes in our ExPEC and InPEC isolates. As previouly reported, quinolone resistance was due to mutations in gyrA in 97% isolates [42]. Resistance phenotypes of ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were associated to S83L + D87N mutations among all Enterobacteriaceae (P < 0.001, [43]). In this study, 62.06% (36/58) of the strains have the gyrA S83L mutation, and 29.31% (17/58) of the strains have the gyrA D87N mutation, resistance phenotypes of ciprofloxacin among 27.59%(16/58) isolates were all harbored mutation S83L + D87N. Nevertheless, gyrA(S83L) single mutation may induce resistance to enorfloxacin and nalidixic acid. Therefore, we need to detected the mutation of gyrA in clinical E. coli isolates, with caution to reduce the development of quinolones resistance. Streptomycin resistance was attributable to the aadA, strA, and strB genes [44]. And in this study, we have found that strA gene was in 82.76% of E. coli isolates (48/58). Among 48 phenotypically identified streptomycin isolates, the prevalence strA and strB genes was 100%(48/48) and 64.58%(31/48), respectively. And this results was consistant with van Overbeek’sstudy [45]. ESBL enzymes confer resistance to penicillins, cephalosporins, monobactams and other antibiotic classes. The TEM, CTX-M and SHV types have been recognized as the most prevalent ESBL genes conferring antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria worldwide [46,47,48]. Kpoda DS [49] revealed the most prevalent ESBL resistance genes were CTX-M (40.1%), TEM (26.2%) and SHV (5.9%) in Enterobacteriaceae. In this study, among 33 phenotypically identified β-lactamases isolates, CTX-M was the most prevalent gene (56.90%), followed by SHV at 41.38%, OXA at 5.17% and TEM at 1.72%. according to the results, we can illustrate the aminoglycosides resistance phenotypes harbored the strA and strB genes, gyrA(S83L) single mutation may induce resistance to enorfloxacin and nalidixic acid. Ciprofloxacin resistance may lead gyrA (S83L + D87N) double mutation in E. coli isolates.

Conclusions

In this study, we find that the extra-intestinal E. coli mainly belong to the phylogenic groups (B2/D), which was considered as ExPEC. The dominant STs of ExPEC included ST117, ST297, ST93, ST1426, and ST10, while the dominant ST of InPEC was ST117. In addition, the multi-resistance rate was 51.72% in all of ExPEC and InPEC isolates. Aminoglycosides resistance was attributable to the strA, and strB genes. Quinolonones and fluoroquinolones was attributable to the mutation of gyrA(S83L/D87N). The prevalence of MDR and XDR of the tested E. coli isolates was 29.31% (17/58) and 10.34%(6/58), respectively. Virulence genes of iss and iutA were significantly different between InPEC and ExPEC, which may be virulence traits to distinguish the virulence of E. coli isolates.

Methods

Isolation and identification of E. coli

A total of 200 E. coli isolates from chicken were collected from Xiangyang, Shishou, Jiangxia, Jinzhou and Tianmen in Central China from 2019 to 2020. InPEC was isolated from feces and intestinal tissues, and ExPEC was isolated from heart, blood, liver, lung, eye and brain tissues. Samples were streaked onto MacConkey and eosin-methylene blue agar (hopebio Co. Ltd., Qingdao, China) plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. E. coli isolates were confirmed using standard biochemical and bacteriological methods [50]. The assumed E. coli were confirmed by PCR amplification of the phoA gene as described previously [51], using the following primers: phoA-F, 5′-GCACTCTTACCGTTACTGTTTACCCC-3′, phoA-R, 5′--3′- TTGCAGGAAAAAGCCTTTCTCATTTT, 1001 bp.

Ethics statement

The sample of sick chickens from farms were euthanized by cervical dislocation and then dissected with aseptic surgical techniques. All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences. All methods were carried out in accordance with the regulation of Hubei Province Laboratory Animal Management Regulations-2005. Collection of organ samples from the farms complies with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) for the reporting of animal experiments.

Determination of phylogenetic groups

Genomic DNA was extracted from E. coli isolates using the boiling method as previously described [52]. Phylogenetic groups of E. coli isolates were determined (groups A, B1, B2, D) using the triplex PCR by amplifying the following gene targets of chuA, yjaA, and TspE4. C2 as described previously [53]. For each PCR reaction, 2 μL samples of cell suspension of the E. coli strains were prepared in 25 μL of sterile deionized water.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

A total of 16 commercially available antibiotic discs (Binhe Microorganism Reagent Co. Ltd., Hangzhou, China) for veterinary and human use, including Extend-spectrum cephalosporins: Ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg), Cefepime (FEP, 30 μg), Cefotaxime (CEF, 75 μg); Non-extend spectrum cephalosporins: Cefuroxime (CXM, 30 μg), Cephalothin (KF, 30 μg); Penicillins: Piperacillin (TZP, 100 μg); Cephamycins: Cefoxitin (FOX, 30 μg); Monobactams: Aztreonam (AZT, 30 μg); Aminoglycosides: Streptomycin (STR, 300 μg), Gentamicin (CN, 120 μg), Spectinomycin (SH, 25 μg); Fluoroquinolones (Ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg), Enrofloxacin (ENR, 5 μg); Quinolones: Nalidixic acid (NA, 30 μg), were prepared for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The diameter of the inhibition zones of 16 commercially available antimicrobial drugs were determined as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute protocols [54]. E. coli ATCC 25922 in the test was used for quality control. The tested strains are classified into MDR, XDR and PDR as previously described by Magiorakos [17].

MLST analysis

Gene amplification and sequencing of the internal fragments from seven specific housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) were performed using PCR as described previously [55]. The allelic profiles of the seven gene sequences and the STs were uploaded to the EnteroBase database (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli), and the E. coli STs were matched. In addition, we performed in silico phylogroup typing and MLST [56]. Phylogenetic and genomic diversity of E. coli strains was constructed by using the UPGMA cluster analysis with START Version 2 (http://pubmlst.org/software/analysis/start2/).

Detection of virulence-associated genes

DNA was extracted from the E. coli isolates and reference strains using the boiling method. The E. coli isolates were analyzed for the presence of the target genes using PCR and sample sequencing. The primer sequences of 13 virulence genes are shown in Table 5. All PCR reactions were carried out on 25 μl samples containing 12.5 μl mix (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China), 8.5 μl ddH2O, 1 μl each of forward and reverse primer, and 2 μl DNA template. PCR amplifications were carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 30 denaturation cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 45 s, amplification at 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR amplification products were separated by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized using a GelDoc XR System (Bio-Rad, Shanghai, China).

Detection of resistance genes

PCR were used to identify genes responsible for resistance to beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, quinolones and fluquinolones. In total, seven antimicrobial-resistant genes, including TEM, SHV, OXA, CTX-M, strA strB, and aadA were detected as previously described [45, 57]. To detect the mutations in gyrA gene, gyrA was amplified and sequenced.

Statistics analysis

All experiments were analyzed using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. Statistical significance is determined when P < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics 19 software (IBM, USA).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GenBank repository, Accession number from MZ346046(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MZ346046) to MZ346423(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MZ346423). The other datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- InPEC :

-

Intestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli

- ExPEC :

-

Extra-intestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli

- MLST:

-

Multilocus Sequence Typing

- STs:

-

Sequence types

References

Li Y, Chen L, Wu X, Huo S. Molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from septicemic broilers. Poult Sci. 2015;94(4):601–11.

Mitchell NM, Johnson JR, Johnston B, Curtiss R 3rd, Mellata M. Zoonotic potential of Escherichia coli isolates from retail chicken meat products and eggs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(3):1177–87.

Rodriguez-Siek KE, Giddings CW, Doetkott C, Johnson TJ, Nolan LK. Characterizing the APEC pathotype. Vet Res. 2005;36(2):241–56.

Najafi A, Hasanpour M, Askary A, Aziemzadeh M, Hashemi N. Distribution of pathogenicity island markers and virulence factors in new phylogenetic groups of uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Folia Microbiol. 2018;63(3):335–43.

Johnson TJ, Wannemuehler Y, Doetkott C, Johnson SJ, Rosenberger SC, Nolan LK. Identification of minimal predictors of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli virulence for use as a rapid diagnostic tool. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(12):3987–96.

Sen K, Shepherd V, Berglund T, Quintana A, Puim S, Tadmori R, et al. American Crows as Carriers of Extra Intestinal Pathogenic E. coli and Avian Pathogenic-Like E. coli and Their Potential Impact on a Constructed Wetland. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1595.

Stromberg ZR, Johnson JR, Fairbrother JM, Kilbourne J, Van Goor A, Curtiss RR, et al. Evaluation of Escherichia coli isolates from healthy chickens to determine their potential risk to poultry and human health. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180599.

Zahraei Salehi T, Derakhshandeh A, Tadjbakhsh H, Karimi V. Comparison and phylogenetic analysis of the ISS gene in two predominant avian pathogenic E. coli serogroups isolated from avian colibacillosis in Iran. Res Vet Sci. 2013;94(1):5–8.

Johnson TJ, Jordan D, Kariyawasam S, Stell AL, Bell NP, Wannemuehler YM, et al. Sequence analysis and characterization of a transferable hybrid plasmid encoding multidrug resistance and enabling zoonotic potential for extraintestinal Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2010;78(5):1931–42.

Stromberg Z, Johnson J, Fairbrother J, Kilbourne J, Van Goor A, Curtiss R, et al. Evaluation of Escherichia coli isolates from healthy chickens to determine their potential risk to poultry and human health. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180599.

Ewers C, Li G, Wilking H, Kiessling S, Alt K, Antao EM, et al. Avian pathogenic, uropathogenic, and newborn meningitis-causing Escherichia coli: how closely related are they? Int J Med Microbiol. 2007;297(3):163–76.

Ronco T, Stegger M, Olsen RH, Sekse C, Nordstoga AB, Pohjanvirta T, et al. Spread of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli ST117 O78:H4 in Nordic broiler production. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):13.

Bozcal E, Eldem V, Aydemir S, Skurnik M. The relationship between phylogenetic classification, virulence and antibiotic resistance of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in Izmir province, Turkey. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5470.

Yang GY, Guo L, Su JH, Zhu YH, Jiao LG, Wang JF. Frequency of Diarrheagenic Virulence Genes and Characteristics in Escherichia coli Isolates from Pigs with Diarrhea in China. Microorganisms. 2019;7(9):308.

Azam M, Mohsin M, Johnson TJ, Smith EA, Johnson A, Umair M, et al. Genomic landscape of multi-drug resistant avian pathogenic Escherichia coli recovered from broilers. Vet Microbiol. 2020;247:108766.

Jakobsen L, Spangholm D, Pedersen K, Jensen L, Emborg H, Agersø Y, et al. Broiler chickens, broiler chicken meat, pigs and pork as sources of ExPEC related virulence genes and resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from community-dwelling humans and UTI patients. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;142:264–72.

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–81.

Hirakata Y, Matsuda J, Miyazaki Y, Kamihira S, Kawakami S, Miyazawa Y, et al. Regional variation in the prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing clinical isolates in the Asia-Pacific region (SENTRY 1998-2002). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;52(4):323–9.

Xiao YH, Wang J, Li Y, Net MOHNARI. Bacterial resistance surveillance in China: a report from Mohnarin 2004-2005. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27(8):697–708.

Jiang HX, Lu DH, Chen ZL, Wang XM, Chen JR, Liu YH, et al. High prevalence and widespread distribution of multi-resistant Escherichia coli isolates in pigs and poultry in China. Vet J. 2011;187(1):99–103.

Wu H, Yi C, Zhang D, Guo Q, Lin J, Mao H, et al. Changes of antibiotic resistance over time among Escherichia coli peritonitis in southern China. Perit Dial Int. 2021;8968608211045272.

Zhang H, Yang Q, Liao K, Ni Y, Yu Y, Hu B, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of aerobic and facultative gram-negative Bacilli from intra-abdominal infections in patients from seven regions in China in 2012 and 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(1):245–51.

Duriez P, Zhang Y, Lu Z, Scott A, Topp E. Loss of virulence genes in Escherichia coli populations during manure storage on a commercial swine farm. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(13):3935–42.

Borzi MM, Cardozo MV, ESd O, AdS P, EAL G, LFd S, et al. Characterization of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from free-range helmeted guineafowl. Braz J Microbiol. 2018;49:107–12.

Guenther S, Grobbel M, Beutlich J, Guerra B, Ulrich RG, Wieler LH, et al. Detection of pandemic B2-O25-ST131 Escherichia coli harbouring the CTX-M-9 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase type in a feral urban brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(3):582–4.

Amani F, Hashemitabar G, Ghaniei A, Farzin H. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in the Escherichia coli isolates obtained from ostrich. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2020;52(6):3501–8.

Huja S, Oren Y, Trost E, Brzuszkiewicz E, Biran D, Blom J, et al. Genomic avenue to avian colisepticemia. mBio. 2015;6(1):e01681–14.

Sadeghi Bonjar MS, Salari S, Jahantigh M, Rashki A. Frequency of iss and irp2 genes by PCR method in Escherichia coli isolated from poultry with colibacillosis in comparison with healthy chicken in poultry farms of Zabol, south east of Iran. Pol J Vet Sci. 2017;20(2):363–7.

Zong B, Liu W, Zhang Y, Wang X, Chen H, Tan C. Effect of kpsM on the virulence of porcine extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363(21):fnw232.

Cieza RJ, Hu J, Ross BN, Sbrana E, Torres AG. The IbeA invasin of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli mediates interaction with intestinal epithelia and macrophages. Infect Immun. 2015;83(5):1904–18.

Stephens CM, Adams-Sapper S, Sekhon M, Johnson JR, Riley LW. Genomic Analysis of Factors Associated with Low Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli Sequence Type 95 Strains. mSphere. 2017;2(2):e00390–16.

Falgenhauer L, Fritzenwanker M, Imirzalioglu C, Steul K, Scherer M, Heudorf U, et al. Near-ubiquitous presence of a vancomycin-resistant enterococcus faecium ST117/CT71/vanB -clone in the Rhine-Main metropolitan area of Germany. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:128.

Fernandes MR, Sellera FP, Moura Q, Souza TA, Lincopan N. Draft genome sequence of a CTX-M-8, CTX-M-55 and FosA3 co-producing Escherichia coli ST117/B2 isolated from an asymptomatic carrier. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;12:183–4.

Papagiannitsis CC, Malli E, Florou Z, Medvecky M, Sarrou S, Hrabak J, et al. First description in Europe of the emergence of enterococcus faecium ST117 carrying both vanA and vanB genes, isolated in Greece. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;11:68–70.

Weber A, Maechler F, Schwab F, Gastmeier P, Kola A. Increase of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus faecium strain type ST117 CT71 at Charite - Universitatsmedizin Berlin, 2008 to 2018. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):109.

Mora A, Lopez C, Herrera A, Viso S, Mamani R, Dhabi G, et al. Emerging avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strains belonging to clonal groups O111:H4-D-ST2085 and O111:H4-D-ST117 with high virulence-gene content and zoonotic potential. Vet Microbiol. 2012;156(3–4):347–52.

Papouskova A, Masarikova M, Valcek A, Senk D, Cejkova D, Jahodarova E, et al. Genomic analysis of Escherichia coli strains isolated from diseased chicken in the Czech Republic. BMC Vet Res. 2020;16(1):189.

Younis GA, Elkenany RM, Fouda MA, Mostafa NF. Virulence and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase encoding genes in Escherichia coli recovered from chicken meat intended for hospitalized human consumption. Vet World. 2017;10(10):1281–5.

Yassin AK, Gong J, Kelly P, Lu G, Guardabassi L, Wei L, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in clinical Escherichia coli isolates from poultry and livestock, China. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185326.

Zhang S, Chen S, Rehman MU, Yang H, Yang Z, Wang M, et al. Distribution and association of antimicrobial resistance and virulence traits in Escherichia coli isolates from healthy waterfowls in Hainan, China. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;220:112317.

Pan YS, Yuan L, Zong ZY, Liu JH, Wang LF, Hu GZ. A multidrug-resistance region containing blaCTX-M-65, fosA3 and rmtB on conjugative IncFII plasmids in Escherichia coli ST117 isolates from chicken. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63(Pt 3):485–8.

Chandran SP, Diwan V, Tamhankar AJ, Joseph BV, Rosales-Klintz S, Mundayoor S, et al. Detection of carbapenem resistance genes and cephalosporin, and quinolone resistance genes along with oqxAB gene in Escherichia coli in hospital wastewater: a matter of concern. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;117(4):984–95.

Fu Y, Zhang W, Wang H, Zhao S, Chen Y, Meng F, et al. Specific patterns of gyrA mutations determine the resistance difference to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:8.

Sundin GW, Wang N. Antibiotic resistance in plant-pathogenic Bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2018;56:161–80.

van Overbeek LS, Wellington EM, Egan S, Smalla K, Heuer H, Collard JM, et al. Prevalence of streptomycin-resistance genes in bacterial populations in European habitats. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2002;42(2):277–88.

Shahcheraghi F, Moezi H, Feizabadi MM. Distribution of TEM and SHV beta-lactamase genes among Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from patients in Tehran. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(11):BR247–50.

Tawfik AF, Alswailem AM, Shibl AM, Al-Agamy MH. Prevalence and genetic characteristics of TEM, SHV, and CTX-M in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Saudi Arabia. Microb Drug Resist. 2011;17(3):383–8.

Dirar MH, Bilal NE, Ibrahim ME, Hamid ME. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and molecular detection of blaTEM, blaSHV and blaCTX-M genotypes among Enterobacteriaceae isolates from patients in Khartoum, Sudan. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:213.

Kpoda DS, Ajayi A, Somda M, Traore O, Guessennd N, Ouattara AS, et al. Distribution of resistance genes encoding ESBLs in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from biological samples in health centers in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):471.

Algammal AM, El-Sayed ME, Youssef FM, Saad SA, Elhaig MM, Batiha GE, et al. Prevalence, the antibiogram and the frequency of virulence genes of the most predominant bacterial pathogens incriminated in calf pneumonia. AMB Express. 2020;10(1):99.

Wang Z, Zuo J, Gong J, Hu J, Jiang W, Mi R, et al. Development of a multiplex PCR assay for the simultaneous and rapid detection of six pathogenic bacteria in poultry. AMB Express. 2019;9(1):185.

Iranpour D, Hassanpour M, Ansari H, Tajbakhsh S, Khamisipour G, Najafi A. Phylogenetic groups of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urinary tract infection in Iran based on the new Clermont phylotyping method. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:846219.

Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(10):4555–8.

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing M100S. 26th ed; 2017.

Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, Colles F, Mensa P, Wieler LH, et al. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60(5):1136–51.

Kallonen T, Brodrick HJ, Harris SR, Corander J, Brown NM, Martin V, et al. Systematic longitudinal survey of invasive Escherichia coli in England demonstrates a stable population structure only transiently disturbed by the emergence of ST131. Genome Res. 2017;27(8):1437–49.

Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decre D, Favier C, Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(3):490–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0500503), the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-41) and Hubei Province Innovation Center of Agricultural Sciences and Technology (2019–620–000-001-017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QLu and TZ participated in the conception and design of the study. HW and LL contributed to the collection of samples. QLu and WZ performed the laboratory work. HS and QLu analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. QLuo and TZ contributed to the analysis and helped in the manuscript discussion section. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The sample of sick chickens from farms were euthanized by cervical dislocation and then dissected with aseptic surgical techniques. All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences. All methods were carried out in accordance with the regulation of Hubei Province Laboratory Animal Management Regulations-2005. Collection of organ samples from the farms complies with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) for the reporting of animal experiments. The animals used in this study were derived from commercial sources, and the owners’ consent was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1 Supplement Table 1

. The results of resistance phenotypes and antimicrobial resistance genes detected in 58 E. coli isolates.

Additional file 2 Supplementary Fig. 1

Raw figure of the Fig. 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Q., Zhang, W., Luo, L. et al. Genetic diversity and multidrug resistance of phylogenic groups B2 and D in InPEC and ExPEC isolated from chickens in Central China. BMC Microbiol 22, 60 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02469-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02469-2