Abstract

Background

Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. n) is an important opportunistic pathogen causing oral and gastrointestinal disease. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. p) is a next-generation probiotic and could serve as a biomarker of gut eubiosis/dysbiosis to some extent. Alterations in the human oral and gut microbiomes are associated with viral respiratory infection. The aim of this study was to characterise the oral and fecal bacterial biomarker (i.e., F. n and F. p) in COVID-19 patients by qPCR and investigate the pharyngeal microbiome of COVID-19 patients through metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS).

Results

Pharyngeal F. n was significantly increased in COVID-19 patients, and it was higher in male than female patients. Increased abundance of pharyngeal F. n was associated with a higher risk of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test (adjusted OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.06 ~ 1.65, P < 0.05). A classifier to distinguish COVID-19 patients from the healthy controls based on the pharyngeal F. n was constructed and achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.843 (95% CI = 0.688 ~ 0.940, P < 0.001). However, the level of fecal F. n and fecal F. p remained unaltered between groups. Besides, mNGS showed that the pharyngeal swabs of COVID-19 patients were dominated by opportunistic pathogens.

Conclusions

Pharyngeal but not fecal F. n was significantly increased in COVID-19 patients, clinicians should pay careful attention to potential coinfection. Pharyngeal F. n may serve as a promising candidate indicator for COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is highly transmissible and pathogenic and has caused a pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which threatens human health and public safety. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (https://covid19.who.int/), as of August 13, 2021, there have been more than 205 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and more than 4.3 million deaths. COVID-19 is a complex multisystem disorder [1]. Common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, fatigue and dry cough. Severe infections can lead to pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure, and even death [2]. In addition to respiratory symptoms, COVID-19 can also experience oral/pharyngeal manifestations, such as sore throat, dry mouth, loss of taste, burning sensation and tongue enlargement [3, 4], and gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting [5, 6].

The pharynx is one of the main entrance into the gastrointestinal tract for microorganisms. Both the pharynx and gastrointestinal tract are recognised as crucial sites for the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection [7, 8]. SARS-CoV-2 infection and invasion in these sites may cause local microbiome dysbiosis and thus lead to secondary bacterial infection [9,10,11]. The host-microbe interactions in the two sites are complex and key for the understanding of the physiology and mechanism of the immune response and microbiome during SARS-CoV-2 infection [8, 12, 13]. Each disease has its own specific microbial characteristics. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) analysis has revealed the pharyngeal microbiota alterations of SARS-COV-2 infected patients [8, 12, 14, 15], and oropharyngeal microbiota alterations were associated with COVID-19 severity [12]. A recent study [7] found that several oral microbial markers (like TM7, Haemophilus, Actinomyces, Prevotella, Oribacterium and Fusobacterium) could specifically identify patients with COVID-19 from the health controls in the random forest model.

Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. n), an anaerobic oral commensal associated with periodontitis, is usually found in respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts [16,17,18,19]. F. n is considered as a biomarker of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients’ lung function deterioration [20] and the development of inflammatory bowel disease and even colorectal cancer [21, 22]. Emerging evidence has demonstrated that the culture supernatant of F. n induced the up-regulation of ACE2 expression in human respiratory epithelial cells and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 [23] and thus F. n may play a synergistic role in the progression of SARS-CoV-2 infection [24]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. p) is an beneficial commensal anaerobe. Tang L et al. reported that the abundance of F. p significantly decreased in the critical COVID-19 patients compared with the general patients [25]. Interestingly, some microbes correlated inversely with SARS-CoV-2 loads in fecal samples from COVID-19 patients could downregulate the expression of ACE2 [26], suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may inhibit microorganisms that are unfavorable for its infection. The concept of F. n and/or F. p serving as non-invasive diagnostic tools for specific diseases has been demonstrated in many studies [20, 27]. Act as the “harmful” and “beneficial” bacteria respectively [27], the potential roles of F. n and F. p in COVID-19 became an interesting future research topic.

In our study, we examined the carriage of F. n in pharyngeal swab samples of COVID-19 patients and healthy controls by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). We also investigated the relative abundance of F. n and F. p in the SARS-CoV-2 positive/negative fecal samples of COVID-19 patients. Besides, metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) was conducted in 10 randomly selected COVID-19 patients’ pharyngeal swabs to characterize the microbial composition and diversity, and then the correlation of the viral loads and the common bacteria were performed.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

A total of 64 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases and 19 healthy controls were included in this study. All the participants are the local residents of Sichuan province, who share similar living environments and dietary habits. Eighty-three samples, including 38 pharyngeal swab samples (28 COVID-19 patients and 10 healthy controls) and 45 fecal samples (36 COVID-19 patients and 9 healthy controls) were collected. The samples were collected only once for each participant. Of the 36 fecal samples from patients, 26 were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and 10 were negative based on our previous study [28]. All samples were stored in sterile containers frozen at − 80 °C instantly after heat-inactivated [29]. The collection, transportation, storage and testing of samples were strictly managed and conducted in the biosafety level-2 (BSL-2) and biosafety level-2 enhanced (BSL-2 +) facilities of Sichuan Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) with full personal protective equipment according to highly pathogenic microorganisms of type II according to the Protocol on Prevention and Control of COVID-19 (seventh edition) [30].

All the participants were diagnosed after laboratory confirmation and categorized into four disease severity, i.e., asymptomatic infection (individuals with positive detection by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and no symptoms), mild illness (patients with mild clinical symptoms and normal CT imaging), moderate illness (Patients with fever and mild respiratory symptoms, radiological findings of pneumonia, and normal range of vital signs), and severe illness (patients with at least one of the the following criteria: respiratory distress ≥30/min; oxygen saturation ≤ 93% in resting state; arterial partial pressure of oxygen [PaO2]/ fraction of inspired oxygen [FiO2] ≤300 mmHg), according to the guidelines of diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 (trial version 7) [31].

Nucleic acid extraction

All the samples were thawed at room temperature and pre-treated as follows. Two hundred milligram of feces were suspended in 2 mL TRIzol (Trizol@ Reagent, Invitrogen, USA), keep still for 10 min and then the supernatant was collected. The pharyngeal swab samples were oscillated on a shaker for 30 s, and the swab lotions were collected. Co-extraction of genomic DNA & total RNA from fecal and pharyngeal swab samples was carried out with NP968 Nucleic Acid Extraction System (Xi’an Tianlong Science & Technology Co., LTD, Xi’an, China). All samples were stored frozen at − 20 °C.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

qPCR was used to determine the relative abundance of bacteria. qPCR was carried out on the ABI 7500 fast real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using QIAampDNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN Sciences, Maryland USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The following sequences of primers we used were as previously described [32, 33]: F. n, forward 5′-CACAAGCTGACGCTGCTAGA-3′, reverse 5′-TTACCAGCTCTTAAAGCTTG-3′(232 bp); F. p, forward 5′-CCATGAATTGCCTTCAAAACTGTT-3′, reverse 5′-GAGCCTCAGCGTCAGTTGGT-3′ (141 bp). The relative abundances of F. n and F. p were calculated in reference to universal 16S rDNA, determined by qPCR using the following primers according to Caporaso et al. [34]: forward 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′, reverse 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′ (291 bp). All primers were synthesized Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate in a single batch, and the average of the cycle threshold (Ct) values was calculated for the following analysis. The abundance was calculated as a relative unit normalized to the universal 16S rDNA of the same sample, using the 2−ΔCt method (ΔCt = mean Ct the target bacterial gene − mean Ct 16S rDNA) [35, 36]. The Ct value is inversely associated with the amount of the target bacterial DNA, while the −ΔCt value is directly proportional to that; therefore, the higher the −ΔCt value, the greater the amount of the target bacterium was in the pharyngeal swab samples.

Library construction and sequencing

Pharyngeal swab samples of 10 COVID-19 patients were randomly selected for metagenomic sequencing. The extracted RNA was quantified using a Qubit RNA High-Sensitivity kit (Invitrogen, USA) before library construction and sequencing. The library preparation was performed by KAPA Stranded RNA-Seq Library Preparation Kit (Kapa Biosystems, USA) following the manufacturer’s operational manual. Specifically, 10 μL total RNA was used as input and was fragmented by heating (94 °C, 8 min) into 150 ~ 200 nt fragments. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized in the presence of specific chemicals to ensure that only RNA was used as templates. Double strand cDNA was purified with Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, USA) after the reaction DNA library was constructed through end-repair, dA-tailing, adaptor-ligation, and 15 cycles PCR amplification. Subsequently, the resulting libraries were denatured, neutralized, and subject to 150 bp pair-end sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, USA) by Chengdu HitGen Pharmaceuticals Inc., China. For each sample, 100 million reads were assigned and the Q30 of all runs ranged from 88 to 91%.

Raw reads were preprocessed using the metaWRAP-Read_qc module [37] with TrimGalore (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/) and BMTagger (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/agarwala/bmtagger/) enabled to remove adapters and host sequences, respectively. Sequences aligned to the SILVA rRNA gene database (https://academic.oup.com/nar/article/41/D1/D590/1069277/) were filtered from the processed datasets using Bowtie2 [38] before the de novo assembly (via MetaWRAP assembly module). Only contigs longer than 500 bp were kept for downstream analysis. Kraken2 [39] was used for taxonomic classification on the contigs, followed by Bracken [40] for the calculation of the species abundance.

Sequence data process

The sequence data were processed through the following steps: a) The bacterial operational taxonomy units (OTUs) were then compared among samples by mothur software [41]. b) The relative abundances of bacterial taxa at the species level were calculated. The top 20 bacteria species were displayed.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and categorical variables as percentage. All statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 26.0 software and GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Normally distributed data were compared by t-test or one-way ANOVA, and non-normally distributed data were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test. Logistic regression was used to screen and verify risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation between the relative abundance of the other bacteria and SARS-CoV-2 or F. n. Biomarker performance was analyzed by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). Significant differences were considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

For the healthy individuals who contributed pharyngeal swab samples, the median age was 43.5 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 31.5 ~ 47.5), with a male:female sex ratio of 1; the healthy fecal donors’ median age was 31.0 years (IQR: 28.0 ~ 44.0), with a male:female sex ratio of 0.8. Moderate illness accounted for the largest proportion of all the enrolled cases (66.67% ~ 70.43%), which was consistent with actually observed tendency [42, 43]. Asymptomatic infection, mild and severe ilness were less than 5% each. Data including age, sex, disease severity, the date of symptom onset (the day when the symptom was noticed), the sampling day and sampling intervals of the confirmed patients were registered (Table 1, Supplementary Tables 1–2). Indeed, retrospective cohort studies indicate that clinical course provides an objective basis for the egregation of patients into groups, and 7 days is an time node of great clinical importance [5, 43, 44]. Although we intended to group the samples by the sampling intervals (intervals from symptom onset to the sampling time) as ≤7 d, 7–14 d and > 14 d, the numbers of pharyngeal swab samples in the latter two groups were too small (n = 3 and 1, respectively) for a proper statistical analysis. Therefore, the latter two groups were combined and subsequently analyzed as a single group.

Changes of the pharyngeal F. n in COVID-19 patients

The −ΔCt values of the COVID-19 patients ranged from −9.03 to 16.52, and those of the healthy ranged from −2.78 to 3.50. As shown in Fig. 1A, the −ΔCt value of the confirmed cases (6.33 ± 5.47) was markedly higher than that of healthy controls (− 0.12 ± 3.77) (P < 0.05), which means that the relative abundance of pharyngeal F. n in COVID-19 patients was significantly higher than that in healthy controls (Fig. 1B). To analyze the impact of sampling intervals on the relative abundance of pharyngeal F. n, the patients were divided into two groups (≤ 7 d and > 7 d) according to the time interval from symptom onset to the sampling time. It was shown that within 7 days after the onset, the average − ΔCt value of COVID-19 patients was higher than that of healthy controls (P < 0.05). The pharyngeal F. n increased in the first week of illness (Fig. 1C, D). Interestingly, sex difference was found in the pharyngeal F. n of COVID-19 patients, and the average − ΔCt value of F. n in male patients was 10 times more than that in females (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1E, F). Furthermore, to determine the changes of pharyngeal F. n in patients with different severity of illness, we compared the −ΔCt level (Fig. 1G) and relative abundance (Fig. 1H) in those with asymptomatic (n = 4), mild (n = 3) and moderate illness (n = 20), and healthy controls (n = 10). It revealed that overall comparisons showed significant differences, while subsequent pairwise comparisons showed no significant differences (P > 0.05). In addition, the −ΔCt values of confirmed cases from different age groups (≤ 30 yrs., 31 ~ 50 yrs., and > 50 yrs) showed no significant difference between these groups (P > 0.05).

Quantitative detection of pharyngeal F. n in COVID-19 patients and healthy controls. The −ΔCt values and the relative abundance of pharyngeal F. n in the confirmed cases were compared with those in healthy controls (A, B), and were compared according to the sampling intervals (C, D), sex (E, F), and severity of illness (G, H). *P < 0.05

Relationship between pharyngeal F. n and risk of viral infection

In the non-adjusted model, increased abundance of pharyngeal F. n was associated with a higher risk of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test (odds ratio [OR] = 1.29, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06 ~ 1.57, P < 0.05). In the adjusted model (adjusted age and sex), the association between −ΔCt value and SARS-CoV-2 positive risk had a similar trend, but with a slightly raised magnitude (adjusted OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.06 ~ 1.65, P < 0.05), indicating that when the −ΔCt value of pharyngeal F. n increased by 1 (the relative abundance of F. n increased by 2), the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection increased by 1.32 times.

The relative abundance of F. n and F. p in the feces of COVID-19 patients didn’t alter much

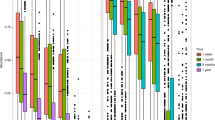

The relative abundance of fecal F. n and F. p in the healthy and confirmed cases was detected by qPCR. Though there was no significant difference (P > 0.05), the −ΔCt values of fecal F. n and F. p in the confirmed case group were slightly smaller than those of healthy controls (Fig. 2A, B). As shown in Fig. 2C and D, when comparing different severity with healthy controls, no significant difference in the −ΔCt values of both F. n and F. p was found (P > 0.05). Furthermore, we analyzed the 36 COVID-19 patients with SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive (n = 26) or negative (n = 10) in feces and found no significant difference in the −ΔCt values of fecal F. n and F. p among the two groups and healthy controls (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2E, F).

Quantitative detection of fecal F. n and F. p in COVID-19 patients and healthy controls. The −ΔCt values of fecal F. n and F. p in the confirmed cases were compared with healthy controls (A, B), and were compared according to the severity of illness (C, D). COVID-19 patients with either negative (−) or positive (+) SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces were compared with the healthy controls (E, F)

Fecal F. n of COVID-19 patients decreased with sampling intervals prolongation

The confirmed cases were divided into two groups (≤ 7 d and > 7 d) according to the feces sampling intervals. It was shown that the fecal F. n of confirmed cases within 7 days after the onset was still at a healthy level (P > 0.05), but it was significantly lower after 7 days (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). In other words, in the cases with shorter feces sampling intervals (≤ 7 d), the relative abundance of fecal F. n had not changed significantly compared with the healthy individuals, but it decreased with the interval prolongation (Fig. 3B). Whereas, no significant difference was found in fecal F. p between the confirmed patients and the healthy controls (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3C and D).

Neither fecal F. n nor F. p influenced the results of SARS-CoV-2 RNA test

Univariate logistic regression models were developed to explore the influence of fecal F. n or F. p on the results of SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection. First, we took the SARS-CoV-2 RNA test results in pharyngeal swabs of both the patients and the healthy indivduls as the dependent variables, and the −ΔCt values of fecal F. n or F. p as the independent variable for univariate logistic regression analysis. The results showed that neither fecal F. n nor F. p were independent risk factors of positive pharyngeal swabs (P > 0.05) (Table 2). Moreover, the influence of fecal F. n or F. p on the results of fecal SARS-CoV-2 RNA test in COVID-19 patients (i.e., negative or positive) was also analysed. However, it’s found that fecal F. n and F. p did not influence the results of fecal SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Identification of a microbial classifier for COVID-19 based on the microbial candidates

A classifier to distinguish COVID-19 patients from the healthy controls based on the pharyngeal F. n was constructed and achieved an AUC of 0.843 (95% CI = 0.688 ~ 0.940, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). A value of 0.60 to 0.70 for AUC indicates that the predictive ability of the model is poor, and 0.8 to 0.9 is considered excellent [45]. Our data reveal that the pharyngeal F.n possessed a good accuracy in distinguishing COVID-19 patients from the healthy controls, the cutoff -ΔCT value for maximum sensitivity (71.43%) and specificity (100%) was 3.50. The sensitivity and specificity of various pharyngeal F.n cutoff -ΔCT values and 95% CI are shown in Table 4. However, the fecal F. n (Fig. 4B) and F. p (Fig. 4C) cannot be used for prediction because of their poor discrimination ability.

Enrichment of opportunistic pathogens in the pharyngeal swabs of COVID-19 patients

The number of OTUs in 10 COVID-19 patients was 613 ± 266. And the relative abundance of SARS-CoV-2 was 0.077% (9#), 0.017% (12#), 0.008% (17#), 0.012% (19#), 0.002% (23#), 0.029% (25#), 0.021% (30#), 0.009% (31#), and 1.982% (32#), respectively. The pharyngeal microbiome of each COVID-19 patient was dominated by the top 20 species, accounting for 28.12 to 58.55% of the total richness (Fig. 5A). The predominant bacterial composition in the pharyngeal swabs of the confirmed patients included Prevotella melaninogenica (4.62% ± 3.17%), Schaalia odontolytica (3.85% ± 3.78%), Rothia mucilaginosa (3.62% ± 3.24%), Neisseria subflava (3.06% ± 3.33%), and Veillonella dispar (2.89% ± 2.29%). Interestingly, 7 out of 10 samples harbored a high abundance of Delftia acidovorans (6.65% ± 13.24%), especially for sample 24#, which showed the least amount of OTUs and the highest relative abundance of Delftia acidovorans (38.87%).

To explore the relationship of the viral loads with the common bacteria in the pharynx of COVID-19 patients, Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 5B, the viral loads in the pharyngeal swabs of COVID-19 patients showed a positive linear correlation with the abundance of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus thermophilus, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Streptococcus constellatus (P < 0.05). Besides, the abundance of F. n correlated with Treponema denticola (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Virus-bacteria interactions are complicated. Our study reveal that the pharyngeal F. n of COVID-19 patients was increased, which deserves special attention. The increased abundance of pharyngeal F. n may promote SARS-CoV-2 infection, for F. n can induce ACE2 expression and proinflammatory cytokine production and thus promote SARS-CoV-2 invasion and infection in oral, respiratory and intestinal epithelial cells [23]. Dysbiosis of microbiome in the oral cavity may impact distant microbiomes via the oral–lung or oral–gut axis [46]. Several studies reported that F. n was detected in the lungs of ICU patients [47, 48]. Increasing evidence has shown that F. n is closely related to the development of inflammatory bowel disease and even colorectal cancer [21, 22]. Hence, we can rationally infer that bacterial coinfection after translocation of F. n would aggravate COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 infection of oral cavity would lead to local microbial dysbiosis [7], and thus make the oral cavity as a reservoir for pathogens. Since the abundance of pharyngeal F. n in COVID-19 patients increased, more focus should be given to preventing periodontal diseases and systemic diseases [49].

Epidemiological data have shown that the morbidity, severity and mortality rates of COVID-19 are higher in males than females [50]. Several possible factors such as the higher expression of ACE2 in male, and sex-based immunological differences driven by sex hormone and X chromosome may be involved [51]. Besides, studies have revealed significant sexual differences in oral hygiene worldwide [52,53,54]. Importantly, we found that the pharyngeal F. n of SARS-CoV-2-positive males was higher than that of females. Based on the above researches and our findings, we speculate that poor oral health may lead to higher morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 in men.

Retrospective cohort studies suggested that 1 week after onset of symptoms, patients with COVID-19 may deteriorate rapidly [5, 43, 44]. Notably, the highest SARS-CoV-2 load was detected in the upper respiratory tract at the time of symptom onset or in the first week of illness [55]. Interestingly, in our results, the pharyngeal F. n was higher than that of healthy controls in the first week of illness. We speculate that pharyngeal F. n may associated with the severity or viral load. Unfortunately, our sequencing data did not reveal the correlation. Further large-sample longitudinal studies are required to confirm this speculation. What’s more, our findings valuable information for the analysis of the pharyngeal and gut microbiota profiles of COVID-19 patients at different time points after SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, understanding whether F. n or F. p alters in the course of COVID-19 will require larger cohort studies, with a focus on longitudinal responses following initial infection.

A diverse gut microbiome promotes the host health, and commensal microbiota can inhibit the invasion and growth of pathogens [56]. Previous studies showed that COVID-19 patients demonstrated a depletion of F. p [25], and the abundance of F. p was inversely correlated with disease severity [26]. Our study, however, found that the abundance of fecal F. p in the infected individuals was not significantly different from those of the healthy, which may partially due to the distinct clinical classification and sampling time.

The dominant oral commensal bacteria in the pharyngeal swabs of the confirmed patients, like Prevotella melaninogenica, Schaalia odontolytica, Rothia mucilaginosa, Neisseria subflava, and Veillonella dispar, was consistent with what previous studies reported [57, 58]. Notably, Prevotella melaninogenica and Rothia mucilaginosa were found overrepresent in the lungs of COVID-19 patients [58, 59]. Additionally, functional enrichment analysis found that over-expressed Prevotella proteins were related to the aggravation of COVID-19 [60], suggesting that Prevotella might play an important role in the progression of COVID-19. Rothia mucilaginosa was reported to be associated with pneumonia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [61]. Unsurprisingly, opportunistic respiratory pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus thermophilus, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Streptococcus constellatus, were found to be positively correlated with viral loads, which in turn explains the respiratory disorders following viral infection. These results demonstrate that vigilance should be maintained when respiratory virus infection occurs, and attention should be paid to the secondary bacterial infection. We also found that the relative abundance Delftia acidovorans significantly increased in the pharyngeal swabs of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals, and it was dominant (38.87%) in sample 24. As reported, Delftia acidovorans was found in tracheal lavage samples of COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care units, with abundance of almost 6% [62]. It is usually nonpathogenic, yet catheter-related infection and pneumonia with lung cavity formation have been reported [63, 64]. Further studies are needed to explore the correlation between Delftia acidovorans and symptoms of COVID-19 such as coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation, and to illustrate the potential mechanism of this dominant species and the decrease of OTUs.

Moreover, our study suggested that the pharyngeal F. n could specifically identify patients with COVID-19 from the healthy controls, and thus it may be a promising candidate indicator (AUC = 0.843) for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Similar to our study, a recent study [7] analysed tongue-coating samples and found that several oral microbial markers (like TM7, Haemophilus, Actinomyces, Prevotella, Oribacterium and Fusobacterium) could serve as an auxiliary tool for the non-invasive diagnosis of COVID-19. Previous investigations have demonstrated the diagnostic value of oral microbiome for colorectal cancer [27], rheumatoid arthritis [65] and even viral diseases [12]. Meanwhile, we first proposed that the pharyngeal F. n could be a reliable indicator for prospective epidemiological monitoring and large-scale screening of COVID-19. We concede that large prospective cohort studies, which account for possible confounders such as age, sex, systemic diseases and oral microbiota composition, are needed to verify the diagnostic efficacy.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study provide potentially significant clinical findings. We reported that the pharyngeal F. n was significantly increased in COVID-19 patients. Thus, more attention from the public and medical communities is warranted for the alterations in the oral microbiome of COVID-19. Effective oral hygiene measures and promotions are necessary to avoid the coinfection by oral microorganisms and the following disease aggravation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Resource (2019nCoVR) (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/ncov/).

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 19

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- ACE2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- TMPRSS2:

-

Transmembrane serine protease 2

- F. n :

-

Fusobacterium nucleatum

- F. p :

-

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- mNGS:

-

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing

- Ct:

-

Cycle threshold

- OTUs:

-

Operational taxonomy units

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

Area under the ROC curve

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Roberts CM, Levi M, McKee M, Schilling R, Lim WS, Grocott MPW. COVID-19: a complex multisystem disorder. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(3):238–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.013.

Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. Jama. 2020;324(8):782–93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12839.

Sinjari B, D'Ardes D, Santilli M, Rexhepi I, D'Addazio G, Di Carlo P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Oral manifestation: an observational, human study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10):3218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103218.

Nuno-Gonzalez A, Martin-Carrillo P, Magaletsky K, Martin Rios MD, Herranz Mañas C, Artigas Almazan J, et al. Prevalence of mucocutaneous manifestations in 666 patients with COVID-19 in a field hospital in Spain: oral and palmoplantar findings. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(1):184–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19564.

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1831–3.e3. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055.

Ren Z, Wang H, Cui G, Lu H, Wang L, Luo H, et al. Alterations in the human oral and gut microbiomes and lipidomics in COVID-19. Gut. 2021:gutjnl-2020-323826. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323826.

Wu Y, Cheng X, Jiang G, Tang H, Ming S, Tang L, et al. Altered oral and gut microbiota and its association with SARS-CoV-2 viral load in COVID-19 patients during hospitalization. npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2021;7(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-021-00232-5.

Shen Z, Xiao Y, Kang L, Ma W, Shi L, Zhang L, et al. Genomic Diversity of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome–Coronavirus 2 in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):713–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa203.

Hanada S, Pirzadeh M, Carver KY, Deng JC. Respiratory viral infection-induced microbiome alterations and secondary bacterial pneumonia. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02640.

Yildiz S, Mazel-Sanchez B, Kandasamy M, Manicassamy B, Schmolke M. Influenza a virus infection impacts systemic microbiota dynamics and causes quantitative enteric dysbiosis. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0386-z.

Ma S, Zhang F, Zhou F, Li H, Ge W, Gan R, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals oropharyngeal microbiota alterations in patients with COVID-19. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00614-3.

Yeoh YK, Zuo T, Lui GC-Y, Zhang F, Liu Q, Li AYL, et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2021;70(4):698. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323020.

Xiong D, Muema C, Zhang X, Pan X, Xiong J, Yang H, et al. Enriched opportunistic pathogens revealed by metagenomic sequencing hint potential linkages between pharyngeal microbiota and COVID-19. Virol Sin. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-021-00391-x.

Rueca M, Fontana A, Bartolini B, Piselli P, Mazzarelli A, Copetti M, et al. Investigation of nasal/Oropharyngeal microbial community of COVID-19 patients by 16S rDNA sequencing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042174.

Takeuchi K, Matsumoto K, Furuta M, Fukuyama S, Takeshita T, Ogata H, et al. Periodontitis is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dent Res. 2019;98(5):534–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034519833630.

van der Maarel-Wierink CD, Vanobbergen JNO, Bronkhorst EM, Schols JMGA, de Baat C. Oral health care and aspiration pneumonia in frail older people: a systematic literature review. Gerodontology. 2013;30(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00637.x.

Terpenning MS, Taylor GW, Lopatin DE, Kerr CK, Dominguez BL, Loesche WJ. Aspiration pneumonia: dental and Oral risk factors in an older veteran population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):557–63. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49113.x.

Li Y, He J, He Z, Zhou Y, Yuan M, Xu X, et al. Phylogenetic and functional gene structure shifts of the oral microbiomes in periodontitis patients. ISME J. 2014;8(9):1879–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.28.

Brennan CA, Garrett WS. Fusobacterium nucleatum — symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):156–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0129-6.

Flanagan L, Schmid J, Ebert M, Soucek P, Kunicka T, Liska V, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum associates with stages of colorectal neoplasia development, colorectal cancer and disease outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(8):1381–90.

Guo S, Lu Y, Xu B, Wang W, Xu J, Zhang G. A simple fecal bacterial marker panel for the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. Front Microbiol. 2019;10(1306). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01306.

Takahashi Y, Watanabe N, Kamio N, Yokoe S, Suzuki R, Sato S, et al. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 and Proinflammatory cytokines induced by the Periodontopathic bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum in human respiratory epithelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1352.

Takahashi Y, Watanabe N, Kamio N, Kobayashi R, Iinuma T, Imai K. Aspiration of periodontopathic bacteria due to poor oral hygiene potentially contributes to the aggravation of COVID-19. J Oral Sci. 2021;63(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.2334/josnusd.20-0388.

Tang L, Gu S, Gong Y, Li B, Lu H, Li Q, et al. Clinical significance of the correlation between changes in the major intestinal Bacteria species and COVID-19 severity. Engineering (Beijing). 2020;6(10):1178–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.05.013.

Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, Yeoh YK, Li AYL, Zhan H, et al. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(3):944–55 e8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.048.

Guo S, Li L, Xu B, Li M, Zeng Q, Xiao H, et al. A simple and novel fecal biomarker for colorectal Cancer: ratio of Fusobacterium Nucleatum to probiotics populations, based on their antagonistic effect. Clin Chem. 2018;64(9):1327–37. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.289728.

Cao R, Bao L, Pan M, Zhang C, Liao H, Liu L, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in fecal samples with different pretreatment methods and PCR kits. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-021-02118-0.

Abraham JP, Plourde BD, Cheng L. Using heat to kill SARS-CoV-2. Rev Med Virol 2020;30(5):e2115. doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2115.

National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. The Protocol on Prevention and Control of COVID-19 (seventh edition) 2020 [updated September 15th; cited 2021 25, April]. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202009/318683cbfaee4191aee29cd774b19d8d/files/f9ea38ce2c2d4352bf61ab0feada439f.pdf.

General Office of the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Guidelines of diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 (trial version 7) 2020 [cited 2020. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989/files/ce3e6945832a438eaae415350a8ce964.pdf.

Zhang XM, Li Y, Gu YX, Zhang CN, Lai HC, Shi JY. Ta-coated titanium surface with superior Bacteriostasis and Osseointegration. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:8693–706. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.S218640.

Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Gratadoux JJ, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16731–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0804812105.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516–22. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000080107.

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.73.

Kim YJ, Lee SM, Park BK, Kim SS, Yi J, Kim HH, et al. Evaluation of propidium monoazide real-time PCR for early detection of viable mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical respiratory specimens. Ann Lab Med. 2014;34(3):203–9. https://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2014.34.3.203.

Uritskiy GV, DiRuggiero J, Taylor J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0541-1.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923.

Wood DE, Lu J, Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):257. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0.

Lu J, Breitwieser FP, Thielen P, Salzberg SL. Bracken: estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2017;3:e104.

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(23):7537. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01541-09.

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

Chen SL, Feng HY, Xu H, Huang SS, Sun JF, Zhou L, et al. Patterns of deterioration in moderate patients with COVID-19 from Jan 2020 to mar 2020: a multi-center, retrospective cohort study in China. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:567296. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.567296.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

Mandrekar JN. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(9):1315–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d.

Mammen MJ, Scannapieco FA, Sethi S. Oral-lung microbiome interactions in lung diseases. Periodontology 2000. 2020;83(1):234–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12301.

de Carvalho Baptista IM, Martinho FC, Nascimento GG, da Rocha Santos CE, Prado RFD, Valera MC. Colonization of oropharynx and lower respiratory tract in critical patients: risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Arch Oral Biol. 2018;85:64–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2017.09.029.

Kumar PS. From focal sepsis to periodontal medicine: a century of exploring the role of the oral microbiome in systemic disease. J Physiol. 2017;595(2):465–76. https://doi.org/10.1113/jp272427.

Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17038. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.38.

Pradhan A, Olsson P-E. Sex differences in severity and mortality from COVID-19: are males more vulnerable? Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-020-00330-7.

Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Ma Y, Zuo W. Single-cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(5):756–9. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202001-0179LE.

Abe M, Mitani A, Hoshi K, Yanagimoto S. Large gender gap in Oral hygiene behavior and its impact on gingival health in late adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124394.

Mamai-Homata E, Koletsi-Kounari H, Margaritis V. Gender differences in oral health status and behavior of Greek dental students: a meta-analysis of 1981, 2000, and 2010 data. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(1):60–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0762.175411.

Furuta M, Ekuni D, Irie K, Azuma T, Tomofuji T, Ogura T, et al. Sex differences in gingivitis relate to interaction of Oral health behaviors in young people. J Periodontol. 2011;82(4):558–65. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2010.100444.

Cevik M, Kuppalli K, Kindrachuk J, Peiris M. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ. 2020;371:m3862. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3862.

Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, Chen J, Tao J, Tian G, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0222-x.

Ai J-W, Zhang H-C, Xu T, Wu J, Zhu M, Yu Y-Q, et al. Optimizing diagnostic strategy for novel coronavirus pneumonia, a multi-center study in Eastern China. medRxiv. 2020:2020.02.13.20022673. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.13.20022673.

Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3.

Han Y, Jia Z, Shi J, Wang W, He K. The active lung microbiota landscape of COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. 2020:2020.08.20.20144014. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.20.20144014.

Khan AA, Khan Z. COVID-2019-associated overexpressed Prevotella proteins mediated host-pathogen interactions and their role in coronavirus outbreak. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(13):4065–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa285.

Maraki S, Papadakis IS. Rothia mucilaginosa pneumonia: a literature review. Infect Dis. 2015;47(3):125–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365548.2014.980843.

de Carvalho FM, Lemos LN, Ciapina LP, Moreira RG, Gerber A, Guimarães APC, et al. Prevalence of bacterial pathogens and potential role in COVID-19 severity in patients admitted to intensive care units in Brazil. medRxiv. 2020:2020.12.22.20248501. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.22.20248501.

Yildiz H, Sünnetçioğlu A, Ekin S, Baran Aİ, Özgökçe M, Aşker S, et al. Delftia acidovorans pneumonia with lung cavities formation. Colomb Med (Cali). 2019;50(3):215–21. https://doi.org/10.25100/cm.v50i3.4025.

Patel D, Iqbal AM, Mubarik A, Vassa N, Godil R, Saad M, et al. Delftia acidovorans: a rare cause of septic pulmonary embolism from catheter-related infection: case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2019;27:100835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2019.100835.

Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, Feng Q, Wang D, Liang D, et al. The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):895–905. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3914.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Special Funds for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 of Sichuan University (2020scunCoV10009), Independent Research Project of State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases (SKLOD202004), and Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020FYS0017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB contributed to the conception and design of the study and wrote the manuscript. CZ performed all statistical analyses; JL and CY helped with data analysis. RC and MP performed the experiments, and critically revised the manuscript. YL contributed to conception and design, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University (WCHSIRB-D-2020-355) and the Ethics Committee of Sichuan CDC (SCCDCIRB-2020-021), and was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, L., Zhang, C., Lyu, J. et al. Beware of pharyngeal Fusobacterium nucleatum in COVID-19. BMC Microbiol 21, 277 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-021-02336-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-021-02336-6