Abstract

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a leading cause of hospital-associated (HA) infections. It has been reported that gastrointestinal colonization (GI) is likely to be a common and significant reservoir for the transmission and infections of K. pneumoniae in both adults and neonates. However, the homologous relationship between clinically isolated extraintestinal and enteral K. pneumoniae in neonates hasn’t been characterized yet.

Results

Forty-three isolates from 21 neonatal patients were collected in this study. The proportion of carbapenem resistance was 62.8%. There were 12 patients (12/21, 57.4%) whose antibiotic resistance phenotypes, genotypes, and ST types (STs) were concordant. Six sequence types were detected using MLST, with ST37 and ST54 being the dominant types. The results of MLST were consist with the results of PFGE.

Conclusions

These data showed that there might be a close homologous relationship between extraintestinal K. pneumoniae (EXKP) and enteral K. pneumoniae (EKP) in neonates, indicating that the K. pneumoniae from the GI tract is possibly to be a significant reservoir for causing extraintestinal infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is part of the healthy human microbiome, providing a potential reservoir for infections. It is known that K. pneumoniae could asymptomatically colonize the skin, mouth, respiratory, and gastrointestinal tracts (GI). K. pneumoniae was detected in approximately 10% of Human Microbiome Project samples collecting from the mouth, nasal cavity, and skin, with an addition of 3.8% stool samples [1]. A 2010 study investigated nasopharyngeal colonization rates for adults and children in Indonesian were 15 and 7%, respectively [2], while another study reported that in the Vietnamese adults, the nasopharyngeal and pharynx colonization rates were 2.7 and 14%, respectively [3]. However, among body sites, GI colonization is likely to be a common and significant reservoir in terms of transmission and infection [4]. In addition, it was reported that K. pneumoniae GI colonization rates in hospitalized patients were estimated to be 20 to 38% [5,6,7,8]. Furthermore, among intensive care unit (ICU) patients, 48% of screened patients with infection were positive for prior GI colonization [9].

Moreover, K. pneumoniae has been recognized as one of the most important opportunistic pathogens in the human gut. Studies have demonstrated that trauma, overuse of antibiotics, and inappropriate diet can destroy the intestinal microecology and decrease probiotics in the gut [10]. These factors could lead to the loss of colonization resistance, allowing for the proliferation of opportunistic pathogens such as K. pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA). These opportunistic bacteria can quickly increase in abundance and has the potential to enter the blood, liver, and lungs, thus leading to enterogenic infections [11, 12]. It was reported that burn injury induces a dramatic dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiome, consequently causing the overgrowth of gram-negative aerobic bacteria, which have the potential to translocate to the extraintestinal sites [13]. Accumulating data [14,15,16] indicate that K. pneumoniae causing late-onset blood infections are of gut origin. However, in fact, we found that gut K. pneumoniae might be a reservoir for late-onset respiratory and blood infections.

Therefore, screening the characterization of the carriage K. pneumoniae isolates in high-risk patients, could help us predict the probability of potential infections. More importantly, the result of homology analysis of K. pneumoniae will provide more evidence. As a result, our study was designed to analyze the relationship between infections and GI colonization among the neonates.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the patients

The clinical data of neonates was retrospectively reviewed, and the details were partially shown in Table 1. The 43 strains of different types of specimens were isolated from 21 neonates: feces (n = 21, 48.8%), sputa (n = 19, 44.2%), and blood (n = 3, 7.0%). All patients were treated with two or more antibiotics for a long time (The usage of time of each antibiotic was shown in Table 1), such as mezlocillin/sulbactam (MSU), moxalactam (MOX), ceftazidime (CAZ), piperacillin /tazobactam (TZP), cefotiam (CTF), and meropenem (MEM). All neonates except neonate 1 were discharged after long-stay treatments. Neonate 1 developed multiple organ failure on account of the septicemia caused by K. pneumoniae. Considering the probability of the treatment failure, the parents of neonate 1 gave up on further treatments. Complete results were shown in Table 2.

Antibiotic sensitivity tests

The results of the antibiotic sensitivity tests in this study showed that the isolates were resistant to different classes of antibiotics (Table 2). All the isolates (43/43) were MDR (multiple drug-resistant) (MDR: Resistant to three or more antimicrobial classes [17].). The proportion of carbapenem resistance was 62.8% among all the isolates (Table 2). In addition, we have compared the resistance rates between the EKP and EXKP. Complete results were shown in supplementary file 1.

Identification of β-lactamase genes and homology analysis of strains

The β-lactamases were divided into four major classes (A to D) by the Ambler scheme [18]. According to the expression of β-lactamase genes, the genotypes were classified into four types (I-IV) I: expressing class A and B β-lactamases; II: expressing class A β-lactamases; III: expressing class A and C β-lactamases; IV: expressing class A and D β-lactamases. The drug resistant phenotypes were divided into five types (A to E) according to the antibiotic sensitive tests. A: resistant to penicillin, penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitors and cephalosporins, sensitive to monobactams and intermediate to carbapenems; B: resistant to penicillin, penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitors, cephalosporins, monobactams and carbapenems; C: resistant to penicillin, penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitors, cephalosporins and monobactams and sensitive to carbapenems; D: resistant to penicillin, penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitors, cephalosporins and carbapenems and sensitive to monobactams; E: resistant to penicillin and penicillin/β-lactamase inhibitors and sensitive to cephalosporins, monobactams and carbapenems. Detailed classifications were shown in Table 2.100% of the isolates (43/43) produced SHV (100%), and most produced CTX-M-15 (79.1%, 34/43) and CTX-M-1 (69.8%, 30/43). Three isolates were identified as NDM-1 positive isolates. There were 12 patients (12/21, 57.1%) whose antibiotic resistance phenotypes, genotypes and the ST types were concordant (When the antibiotic resistance phenotypes, genotypes, and the ST types of the strains were concordant, the paired isolates might be homologous.)Complete results were shown in Table 2.

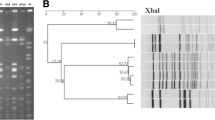

The STs of the isolates were determined and numbered using the international database of the Institute Pasteur website, which showed an immense diversity with the results presented in Table 2. The isolates were distributed in six types of STs (ST37, 54,70, 29,1083,1436), among which ST37 and ST54 were the most frequently seen STs. Besides, our data indicated that the ST37 was the main ST type in both the extraintestinal and enteral isolates. The concatenated sequences of all seven loci were used to draw a phylogenetic tree. The results showed that ST37 and ST1083 were homologous, which belong to CC37 clone complex [19]. The result of PFGE also demonstrated that ST37 and ST1083 were homologous. Complete results were shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

The UMPGA dendrogram, sequence types (STs), and genotypes of 43 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from 21 patients. The tree shows that ST37 and ST1083 were related. In our previous study, ST37 and ST1083 belong to the same clone complex CC37 [19]

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis

Among five patients, the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis (PFGE) showed the paired isolates from patients 12,15 and 21 had identical and > 90% similarity in PFGE patterns (Fig. 2).

Discussion

K. pneumoniae is known as the common cause of respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and bloodstream infections (BSIs) [20]. K. pneumoniae typically colonize human mucosal surfaces, including nasopharynx and GI tract. The colonization rate varies among different body sites, and also is different between the community-acquired (CA) K. pneumoniae and the hospital-acquired (HA) K. pneumoniae. It is estimated that the rate of CA nasopharynx colonization was about 11%. The rate in adults is typically higher than that in children [20]. However, the rate of HA nasopharynx colonization is slightly higher, up to 19% [21]. Compared to the nasopharynx, the CA GI colonization rate is estimated to be around 3.9 ~ 5.9% [9]. Furthermore, the HA GI colonization rate varies from 23 to 30% [22, 23]. It was reported that the GI carriage of K. pneumoniae was related to the subsequent HA infections [6]. In 2017, a study which explored the association between GI colonization and infections. Showed that the rate of K. pneumoniae infections was much higher for the GI colonization patients compared with the patients who were culture-negative (16% vs 3%) [9]. However, for the neonates, intestinal colonization occurred immediately after birth [24]. When some pathogens colonize the gut, it might result in the later subsequent infections. Compared to the neonates who were non-colonized, the likelihood of the colonized-neonates developing subsequent infections was remarkably higher (24.8% VS 1.9%). The percentages of the nasopharynx and GI K. pneumoniae colonization were respectively 29 and 36.8% in the hospitalized neonates [25]. Furthermore, a study showed that the GI K. pneumoniae could invade and penetrate the intestinal epithelium, which indicated that GI K. pneumoniae could cause extraintestinal infections. This transcellular translocation mechanism is exploited by K. pneumoniae strains from the gut caused systematic infections by this transcellular mechanism [26]. Although there was a close relationship between colonization and infections, the homologous relationship between the GI colonized isolates and extraintestinal isolates has not been reported yet.

In our study, all the isolates (43/43) were MDR K. pneumoniae, and 27 strains were resistant to carbapenems with a drug resistance rate of 62.8%. The proportion was moderately higher than 54% in adult that published by World Health Organization [27], while considerably higher than the proportions of 24.7 and 29.8% found in previous studies in the neonates [28, 29].

One hypothesis indicating that GI colonization was likely to be a significant reservoir in terms of transmission and infections [4]. Furthermore, some drug-resistant genes which were mediated by plasmids could be acquired or lost during bacterial translocation [20]. Based on this hypothesis, the drug-resistant phenotypes might be affected by the loss or acquisition of the β-lactamase genes. In our study, the CTX-M-1, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, and TEM-1 were expressed differently between feces and other samples. These genes belong to plasmid-mediated ESBLs [18]. In this case, the drug resistant genotypes and phenotypes were divided into different groups as per the antibiotic sensitivity tests and the expressions of the β-lactamase genes. The results showed that there were 12 patients (12/21, 57.1%) whose paired isolates might be homologous. The data demonstrated that the GI tract might be a significant reservoir for causing extraintestinal infections.

The majority of the isolates were resistant to β-lactam antibiotics. The resistance observed in the present study might be attributed to the expression of resistance genes such as β-lactamase genes. NDM-1 appeared in 7% of isolates, which was first identified in 2006. After it was first identified, it was predominantly found in K. pneumoniae and E. coli. Since 2010, the bacteria producing NDM-1 had been reported worldwide. In China, NDM-1 producing K. pneumoniae has been frequently reported in neonates [30, 31]. The STs of blaNDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae mainly included ST11, ST16, ST20, ST37, ST70, ST147, and ST1419 [32,33,34,35]. But our data indicated that the ST54 was the only NDM-1 producing type. In most cases, bacteria with NDM-1 were resistant to almost all antibiotics. Moreover, the dissemination has been facilitated by horizontal gene transfer. That being so, reliable detection and surveillance are of great importance in preventing the clonal outbreaks. Although these isolates showed high drug resistance and high rates of resistance genes, just one neonate (patient 1) acquired a poor prognosis upon treatment with antibiotics.

To confirm whether the isolate pairs were homologous or not, a UMPGA tree was drawn by employing MEGAX to further analyze the homology among the different isolates from the same patients. Excluding the completely concordant strains, the analysis of the homology among ST37 and ST1083 should be confirmed. According to the analyses, ST37 and ST1083 were in the same cluster (two alleles of the 7 housekeeping genes differed), concluding that the two were closely related and the results validated a great deal of our previous research [19]. The PFGE also indicated that ST37 and ST1083 were homologous. Moreover, our data indicated that ST37 were the main epidemic clones in the Neonate Ward, which showed consistency with what found in other studies [19, 30]. It is discovered that ST37 are presumably to be a potential high-risk MDR K. pneumoniae clonal lineage [36]. In our study, the results of MLST were consist with PFGE. Furthermore, it is reported that carriage of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) in the GI tract may precede and possibly serve as a source for subsequent clinical infections in approximately 9% of carriers [37, 38]. And these carriers may act as a significant reservoir for the dissemination of CRKP in the healthcare facilities [39,40,41]. Combined with our study, active surveillance for detecting CRKP colonization is critical for preventing the CRKP from spreading. Besides, according to the guidance of CDC for control of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), screening rectal cultures of CRE is an important strategy for CRE prevention [42].

The main strength of our study is the use of multiple approaches to characterize the isolates and their similarity to one another in the neonates. However, there are several limitations. First, neonatal cases are difficult to collect, only 21 neonatal patients were collected for analyzing. Second, because of the limitation of experimental conditions, only 10 paired strains from 5 patients were selected randomly for PFGE.

Conclusion

In this study, we found there was an apparently close phylogenetic relationship between the extraintestinal and enteral strains. This conclusion is a reminder that K. pneumoniae which colonizes in the intestine can also induce infections in other parts of the body. Once the Amp C, KPC, and NDM-1 genes are successfully transferred, acquired resistance will potentially cause severe infections. Therefore, the hospital should screen the CRKP which colonized in the gut to limit and prevent current and future outbreaks.

Methods

Bacterial strains and clinical characteristic

Samples isolated from the feces, sputa, and blood were collected from the neonates infected with K. pneumoniae. All the sputum samples were collected from the neonates who were diagnosed with neonatal pneumonia, acute bronchopneumonia, and bronchitis. Diagnoses were made based on both clinical and radiologic findings. The strains isolated from the same patient were paired. Forty-three isolates of K. pneumoniae were collected from feces, sputa, and blood of 21 neonates. All the neonates were admitted to the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, China, from July 2014 to April 2015. All the data of the neonates were collected by chart review from the hospital’s unified electronic database. These isolates were identified by using the BD Phoenix 100 Automated Microbiology System (BD Diagnostic Systems, MD, USA). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 were used as quality control strains.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

All bacterial isolates were subjected to antibiotic sensitivity tests using the agar dilution method following the standard antibiotic susceptibility test chart from the CLSI guidelines [43]. The results were interpreted by measuring the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) which were determined as the lowest concentration of antibiotics at which the strains showed no visible growth after overnight incubation at 37 °C. The isolates resistant to carbapenems were verified with the Kirby-Bauer/disk diffusion method following the CLSI guidelines [43].

PCR and sequencing for resistant genes

Genomic DNA from the isolates was prepared for PCR and genetic analyses using the TIAN amp Bacterial DNA Kit (Tian Gen Biotech, Beijing, Co., Ltd.). The β-lactamase antibiotic resistance genes which were prevalent in K. pneumoniae were mainly detected (including NDM-1, KPC-2, OXA-1, OXA-2, OXA-9, OXA-48, OXA-181, CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2, CTX-M-8, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, CMY-4, CMY-8, TEM-1, and SHV; Table 3). These resistance genes were screened through PCR assays, and the PCR products were sent to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai)Co., Ltd. for sequencing analysis. The entire sequence of each gene was compared to the sequences in the Gen-Bank nucleotide database at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/.

Multiple locus sequence typing

The MLST assay was performed as previously described [43]. Briefly, seven K. pneumoniae housekeeping genes (infB, tonB, pgi, gapA, phoE, rpoB, and mdh) were amplified and sequenced. Alleles and STs were assigned using the K. pneumoniae MLST database (http://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html).

Phylogenetic relationship

The products of the housekeeping genes were compared and analyzed by utilizing the program BLAST. To explore the phylogenetic relationship among the isolates, the seven loci (rpoB, gapA, mdh, pgi, infB, phoE, and tonB) of each isolate were concatenated and aligned using the Clustal X program. An evolutionary tree for the data set was formed by the UMPGA tree using the software MEGA X. The stability of the phylogenetic relationship was evaluated by bootstrap analysis based on 1000 replicates [46]. The tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree [47].

PFGE

We performed PFGE analysis using Bio-Rad syste m[48]. First, bacterial suspension was prepared, and then the restriction enzyme XbaI was used. Second, the electrophoretic gel was imprinted, and stained with ethidium bromide. Finally, electrophoretic images were analyzed with the software BioNumerics (Applied Maths, Inc.). A similarity coefficient > 80% was selected to define a major cluster.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed with SPSS 19.0 statistical software. Categorical variables were evaluated by the Fisher’s exact test. Values were presented as percentages of the group from which they were derived (categorical variables). A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bio Numerics 5.10 software was used for PFGE.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

02 February 2021

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

Abbreviations

- HA:

-

Hospital-associated

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal colonization

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reactions

- MLST:

-

Multiple Locus Sequence Typing

- EXKP:

-

Extraintestinal K. pneumoniae

- EKP:

-

Enteral K. pneumoniae

- STs:

-

ST types

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- PA:

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- MICs:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentrations

- MSU:

-

Mezlocillin/sulbactam

- MOX:

-

Moxalactam

- CAZ:

-

Ceftazidime

- TZP:

-

Piperacillin /tazobactam

- CTF:

-

Cefotiam

- MEM:

-

Meropenem

- MDR:

-

Multiple drug-resistant

- PFGE:

-

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis

- UTIs:

-

Urinary tract infections

- BSIs:

-

Bloodstream infections

- CA:

-

Community-acquired

- HA:

-

Hospital-acquired

- CRKP:

-

Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae

- CRE:

-

Carbapenem -Resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- NDM:

-

New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase

- KPC:

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase

- OXA:

-

Oxacillinase

- CTX-M:

-

Cefotaximase

- CMY:

-

Cephamycinase

- TEM:

-

Temoneira

- SHV:

-

Sulfhydryl Variable

References

Conlan S, Kong HH, Segre JA. Species-level analysis of DNA sequence data from the NIH human microbiome project. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47075.

Farida H, Severin JA, Gasem MH, et al. Nasopharyngeal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae and other gram-negative bacilli in pneumonia-prone age groups in Semarang, Indonesia. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1614–6.

Dao TT, Liebenthal D, Tran TK, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae oropharyngeal carriage in rural and urban Vietnam and the effect of alcohol consumption. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91999.

Dorman MJ, Short FL. Genome watch: Klebsiella pneumoniae: when a colonizer turns bad. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:384.

Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:589–603.

Selden R, Lee S, Wang WL, Bennett JV, Eickhoff TC. Nosocomial klebsiella infections: intestinal colonization as a reservoir. Ann Intern Med. 1971;74:657–64.

Filius PM, Gyssens IC, Kershof IM, et al. Colonization and resistance dynamics of gram-negative bacteria in patients during and after hospitalization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2879–86.

Rose HD, Babcock JB. Colonization of intensive care unit patients with gram-negative bacilli. Am J Epidemiol. 1975;101:495–501.

Gorrie CL, Mirceta M, Wick RR, et al. Gastrointestinal carriage is a major reservoir of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in intensive care patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:208–15.

Holmes AJ, Chew YV, Colakoglu F, et al. Diet-microbiome interactions in health are controlled by intestinal nitrogen source constraints. Cell Metab. 2017;25:140–51.

Cordero L, Rau R, Taylor D, Ayers LW. Enteric gram-negative bacilli。bloodstream infections: 17 years' experience in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:189–95.

Wu H, Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Linking microbiota to human diseases: a systems biology perspective. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:758–70.

Earley ZM, Akhtar S, Green SJ, et al. Burn injury alters the intestinal microbiome and increases gut permeability and bacterial translocation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129996.

Madan JC, Salari RC, Saxena D, et al. Gut microbial colonisation in premature neonates predicts neonatal sepsis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:456–62.

Carl MA, Ndao IM, Springman AC, et al. Sepsis from the gut: the enteric habitat of bacteria that cause late-onset neonatal bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1211–8.

Stewart CJ, Marrs EC, Nelson A, et al. Development of the preterm gut microbiome in twins at risk of necrotising enterocolitis and sepsis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73465.

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81.

Bradford PA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:933–5.

Li P, Wang M, Li X, et al. ST37 Klebsiella pneumoniae: development of carbapenem resistance in vivo during antimicrobial therapy in neonates. Future Microbiol. 2017;12:891–904.

Martin RM, Bachman MA. Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:4.

Pollack M, Charache P, Nieman RE, et al. Factors influencing colonisation and antibiotic-resistance patterns of gram-negative bacteria in hospital patients. Lancet. 1972;2:668–71.

Davis TJ, Matsen JM. Prevalence and characteristics of Klebsiella species: relation to association with a hospital environment. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:402–5.

Martin RM, Cao J, Brisse S, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Colonizing and Infecting Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. mSphere. 2016;1:e00261–16.

Basu S. Neonatal sepsis: the gut connection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:215–22.

Song JY.2018.MD thesis. The Main Pathway Transmission and Genetics Studies on Drug-resistant Genes of NICU Klebsiella pneumoniae. North China University of Science and Technology. Tang Shan, CA.

Hsu CR, Pan YJ, Liu JY, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae translocates across the intestinal epithelium via rho GTPase- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent cell invasion. Infect Immun. 2015;83:769–79.

Unemo M, Lahra MM, Cole M, Galarza P, Ndowa F, Martin I, Dillon JR, Ramon-Pardo P, Bolan G, Wi T. World Health Organization global Gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance program (WHO GASP): review of new data and evidence to inform international collaborative actions and research efforts. Sex Health. 2019;16:412–25.

Al-Dhaheri AS, Al-Niyadi MS, Al-Dhaheri AD, Bastaki SM. Resistance patterns of bacterial isolates to antimicrobials from 3 hospitals in the United Arab Emirates. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:618–23.

Khorasani G, Salehifar E, Eslami G. Profile of microorganisms andantimicrobial resistance at a tertiary care referral burn Centre in Iran: emergence of Citrobacter freundii as a common microorganism. Burns. 2008;34:947–52.

Zhu J, Sun L, Ding B, et al. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST76 and ST37 isolates in neonates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:611–8.

Jin Y, Shao C, Li J, et al. Outbreak of multidrug resistant NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from a neonatal unit in Shandong Province. China PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119571.

Zhang X, Li X, Wang M, et al. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae causing neonatal infection in a teaching hospital in mainland China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4349–51.

Yu J, Wang Y, Chen et al. Outbreak of nosocomial NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST1419 in a neonatal unit. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2017; 8:135–139.

Zhou J, Li G, Ma X, Yang Q, Yi J. 2015. Outbreak of colonization by carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal intensive care unit: investigation, control measures and assessment. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:1122–4.

Li J, Zou MX, Wang HC, et al. An outbreak of infections caused by a Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 clone coproducing Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-2 and RmtB in a Chinese teaching hospital. Chin Med J. 2016;129:2033–9.

Guo Q, Spychala CN, McElheny CL, Doi Y. Comparative analysis of an IncR plasmid carrying armA, blaDHA-1 and qnrB4 from Klebsiella pneumoniae ST37 isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:882–6.

Schechner V, Kotlovsky T, Kazma M, et al. Asymptomatic rectal carriage of blaKPC producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: who is prone to become clinically infected? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:451–6.

Borer A, Saidel-Odes L, Eskira S, et al. Risk factors for developing clinical infection with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in hospital patients initially only colonized with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:421–5.

Bilavsky E, Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. 2010. How to stem the tide of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae? : Proactive versus reactive strategies. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:327–31.

Wiener-Well Y, Rudensky B, Yinnon AM, et al. Carriage rate of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in hospitalised patients during a national outbreak. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74:344–9.

Calfee D, Jenkins SG. Use of active surveillance cultures to detect asymptomatic colonization with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in intensive care unit patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:966–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidance for control of infections with carbapenem-resistant or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in acute care facilities. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:256–60.

Wayne. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twenty-first informational supplement M100-S21. USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012.

Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4178–82.

Yu Y, Ji S, Chen Y, et al. Resistance of strains producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and genotype distribution in China. J Infect. 2007;54:53–7.

Reddy DM, Aspatwar A, Dholakia BB, Gupta VS. Evolutionary analysis of WD40 superfamily proteins involved in spindle checkpoint and RNA export: molecular evolution of spindle checkpoint. Bioinformation. 2008;2:461–8.

Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–25.

Fung CP, Chang FY, Lee SC, Hu BS, Kuo BI, Liu CY, Ho M, Siu LK. A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumonia liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis? Gut. 2002;50:420–4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the director of our department for providing us with the experiment site.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hunan Science and Technology Innovation Project, China (grant number 2017SK50122) and the New medical technology project of the Second Xiangya Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMC performed the test, analyzed data, drafted, and writing the manuscript. MW obtained funding for the project and helped to interpret the data and contributed to drafting the manuscript. XPL assisted in the data analysis. PLL helped us to collect the data. JJT, KZ and CL edited and read the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained written informed consent both at recruitment and soon after delivery from each mother. This study was approved by the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University ethics committee (20200313).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The funding bodies played the role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Cm., Wang, M., Li, Xp. et al. Homology analysis between clinically isolated extraintestinal and enteral Klebsiella pneumoniae among neonates. BMC Microbiol 21, 25 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-020-02073-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-020-02073-2