Abstract

Background

Welsh onion constitutes an important crop due to its benefits in traditional medicine. Nitrogen is an important nutrient for plant growth and yield; however, little is known about its influence on the mechanisms of Welsh onion regulation genes. In this study, we introduced a gene expression and amino acid analysis of Welsh onion treated with different concentrations of nitrogen (N0, N1, and N2 at 0 kg/ha, 130 kg/ha, and 260 kg/ha, respectively).

Results

Approximately 1,665 genes were differentially regulated with different concentrations of nitrogen. Gene ontology enrichment analysis revealed that the genes involved in metabolic processes, protein biosynthesis, and transportation of amino acids were highly represented. KEGG analysis indicated that the pathways were related to amino acid metabolism, cysteine, beta-alanine, arginine, proline, and glutathione. Differential gene expression in response to varying nitrogen concentrations resulted in different amino acid content. A close relationship between gene expression and the content of amino acids was observed.

Conclusions

This work examined the effects of nitrogen on gene expression and amino acid synthesis and provides important evidence on the efficient use of nitrogen in Welsh onion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nitrogen (N) is considered one of the most important nutrients required for plant growth and yield [1, 2]; therefore, crop yield and productivity have a strong relationship with the supply of nitrogen. The demand is fulfilled by the application of nitrogen fertilizers in the field, which come in various chemical forms, such as inorganic NO3−, NH4+, and organic urea, which is the most commonly applied nitrogen fertilizer worldwide [3]. However, excessive use of urea increases production costs and environmental pollution. Therefore, increasing nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) is important for sustainable agriculture.

Welsh onion (Allium fistulosum L.) is an important economical crop widely cultivated throughout the world, particularly in Asian countries [4]. It is often used as an ingredient for its special flavor and aroma and is considered a good source of nutrition; it is also used in traditional medicine [5]. However, despite its nutritional and medicinal value, information about this non-model plant’s response to nitrogen is limited.

NUE in plants is highly complex and can induce diverse processes at both physiological and molecular levels. Ribonucleic acid-sequencing (RNA-seq) technology is a powerful tool that has been widely used to quantify gene expression levels in biological studies. RNA-seq was successfully applied in discovering key genes in populous [6], cucumber [7], Arabidopsis thaliana, and wheat [8, 9]. It was also used in genomics studies on A. fistulosum [5, 9], where the gene expression of different varieties of A. fistulosum was used [10]. To date, transcriptome studies have been carried out on many crops after nitrogen treatment, including Arabidopsis [11, 12], maize [13], poplar [14], and cucumber [7].

Amino acids are important nitrogen storage compounds in plants [15]. As the biosynthesis of amino acids requires nitrogen and carbon elements, nitrogen nutrition [16] and photosynthesis [17] are crucial, and after the uptake of nitrogen, glutamate synthase (GOGAT) and glutamine synthetase (GS) play vital roles in nitrogen assimilation in plants [18]. The relationship between specific genes and amino acids has been reported in other crops [19]. The abundance of nitrogen can strongly affect the biosynthesis of amino acids of tea plants, thus influence tea quality [20]. However, little information is available regarding the metabolism of nitrogen and amino acids and the gene regulation network in A. fistulosum.

In this study, we introduced differentially expressed gene (DEG) regulations and amino acids to investigate the relationship between nitrogen supply and metabolism in Welsh onion. We used RNA-seq technology and measured amino acids to explore the gene regulation network in A. fistulosum. There was a close relationship between gene expression and the content of amino acids; therefore, specific DEGs might improve the understanding of the influence of nitrogen in Welsh onion.

Results

Sequencing and de novo assembly

To study the global transcriptional response of A. fistulosum to various urea concentrations (N0, N1, and N2), we analyzed samples subjected to various nitrogen treatments using RNA-seq. De novo assembly was performed using a Trinity assembler, and the length distributions of the contigs, transcripts and unigenes are shown in Table 1. The next generation short-read sequences were assembled into 536,449 transcripts with an average length of 822.26 bp. The transcripts were subjected to cluster and assembly analyses. The longest transcript was taken as the sample unigene for data. A total of 247,703 unigenes with an average length of 634.16 bp were obtained. The N50 values of the transcripts and unigenes were 1,343 and 948 bp, respectively. The GC content of Welsh onion unigenes was 37.62 %.

Functional annotation and classification

All assembled unigenes were subjected to BLASTx similarity analysis with an E-value of 10−5 against different NCBI databases, including NR, Gene Ontology (GO), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups (eggNOG), and Swiss-Prot. As shown in Table 2, there were 59,689 unigenes (24.1 %) annotated in the NR database, 22,292 (9 %) annotated in the GO database, 5,901 (2.38 %) annotated in the KEGG database, 56,192 (22.69 %) annotated in the eggNOG database, and 47,305 (19.1 %) matched in the Swiss-Prot database.

Differentially expressed genes in response to nitrogen

Table 3 compares plants without nitrogen (N0), 369/364 DEGs were up/down-regulated in the Welsh onion treated with half-levels of nitrogen (N1), 414/367 DEGs were up/down-regulated after full levels of nitrogen treatment (N2), and 387/275 DEGs were up/down-regulated in the pseudostems after full levels of nitrogen treatment with N1 as the control. As shown by the Venn diagram (Figs. 1), 224 DEGs overlapped in N1 vs. N0 and N2 vs. N0.

Seven genes were identified involving in N-uptake or assimilation from the transcriptome data. The lowest expression level of nitrate reductase (NR) and the highest expression level of GS corresponded to plants treated with the highest nitrogen concentration (Fig. 2). Down-regulation was observed for argininosuccinate synthase (AsuS) in all the groups. The order of the Welsh onion, according to the expression level of argininosuccinate lyase (ASL) and GOGAT, was N1>N2>N0, whereas the order for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) was the opposite (N1<N2<N0). The expressions of ammonium transporter (AMT) were not differential in any of the groups in response to nitrogen treatment.

Heatmap of the DEGs (FPKM) of Welsh onion after treatment with different concentrations of nitrogen: N0: nitrogen-free; N1: half nitrogen; N2: full nitrogen; AsuS: argininosuccinate synthase; ASL: argininosuccinate lyase; NR: nitrate reductase; AMT: ammonium transporter; GDH: glutamate dehydrogenase; GOGAT: glutamate synthase; GS: glutamine synthetase

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

The DEGs in comparative conditions were subjected to GO enrichment analysis to predict the biological functions of candidate genes in response to nitrogen. These transcripts were further classified into three major categories, but most of the assignments belonged to biological processes and molecular function. Significant GO terms were selected with a cut-off P-value of 0.05. Only one term (GO:0004766) belonging to molecular function was obtained between nitrogen-free and full levels of nitrogen treatment (data not shown). Six GO terms were classified as molecular function, and 12 GO terms were classified as biological processes (Tables 4 and 5) in the other two comparable groups. Among them, six terms were related to the biosynthesis of peptides or amino acids (GO:0004766, GO:0006412, GO:0043043, GO:0043604, GO:0006518, GO:0043603), while one term was related to the biosynthesis of nitrogen compound (GO:0044271). Four terms were related to transporter activity (GO:0080161, GO:0010329, GO:0015562, GO:0009926). These results indicated that candidate genes were closely related to the metabolism, biosynthesis, and transportation of nitrogen, and especially with amino acid metabolism.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed to categorize the biochemical pathways of DEGs. To better understand the biological functions and pathways of candidate genes in the Welsh onion with different N-supplements, all of the DEGs were annotated in the KEGG database. The pathways with P-value < 0.05 were regarded as significant. In terms of the enrichment analysis of the DEGs between nitrogen-free and half nitrogen treatment, two pathways (ko00190 and ko00904) were detected, which related to oxidative phosphorylation and diterpenoid biosynthesis, respectively (data not shown). Our results revealed that 21 pathways were involved after nitrogen treatment (Tables 6 and 7), with four similar pathways among different nitrogen concentrations (ko00270, ko00410, ko00330, ko00480). Interestingly, all of these pathways were related to amino acid metabolism. All the findings indicated that the level of nitrogen can affect the biosynthesis of amino acids.

Regulation of amino acid content in response to different concentrations of nitrogen

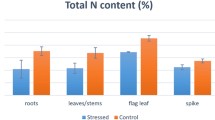

After nitrogen treatment, the pseudostems contained significantly more threonine and proline than the nitrogen-free group (Fig. 3). The amounts of two amino acids were similar after different concentrations of nitrogen. The contents of glutamate, alanine, lysine, and histidine did not show marked differences with altered levels of nitrogen. Meanwhile, higher contents of cysteine and arginine were detected in the nitrogen-free samples. Higher contents of cysteine may attribute to the higher expression level of cysteine synthase (CS) corresponded to nitrogen-free group (data not shown). A higher expression level of genes was observed that encoded spermidine synthase involved in the biosynthesis pathway of proline, beta-alanine, cysteine, arginine, and glutathione (Tables 5 and 8). As the precursor of spermidine, decreased level of arginine was detected after nitrogen treatment. Alpha-enolase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase genes were also up-regulated. To show the effects of the candidate genes, we proposed a regulation network of nitrogen metabolism and amino acid synthesis (Fig. 4).

The DEGs of pathways related to nitrogen transport and assimilation: CPS: carbamoyl phosphate synthase; GS: glutamine synthetase; GOGAT: glutamate synthase; GDH: glutamate dehydrogenase; AsuS: argininosuccinate synthase; ASL: argininosuccinate lyase; Ure: urease; PUT: putrescine; SPDS: spermidine synthase; SPD: spermidine; SPM: spermine; AMT: ammonium transporter; NR: nitrate reductase; red represents the transcripts positively regulated by urea treatment; blue represents transcripts negatively regulated by urea treatment

Discussion

Transcriptome analysis is an effective approach in identifying metabolic pathways and novel plant genes without a genomic sequence [21, 22]. The importance of using nitrogen efficiently in plants’ growth and yield has become a very attractive scientific topic. NUE includes the uptake and assimilation of nitrogen into plants, thus, identifying the genes involved in this process is currently a key step. Several genes involved in the use of nitrogen were reported in Arabidopsis and rice [15], but although Welsh onion is an important crop, little is known about the role of these types of genes. In this study, RNA-seq was used to investigate the genes involved in NUE in response to different concentrations of nitrogen. Differential expression behavior of genes involved in N-uptake and assimilation and urea cycle were detected in response to nitrogen treatment (Fig. 4). Genes encoding for enzymes of N-assimilation, including NR and GDH, and gene for AsuS of urea cycle were found to be down-regulated. However, genes for GS and GOGAT of N-assimilation, and ASL of urea cycle were up-regulated after nitrogen supply.

Nitrogen uptake includes the assimilation and remobilization of organic nitrogen in the whole plant [23]. Urea had a repressive effect on NO3− influx but promoted NH4+ uptake in Arabidopsis [24]. This was consistent with the phenomena introduced in Welsh onion after urea treatment with a down-regulated expression pattern of a nitrogen uptake gene (NR) (Fig. 2). NR is a key enzyme that catalyzes the first step of nitrate assimilation, and its reduced expression under nitrogen stress indicated the regulation of this enzyme in rice [25]. The down-regulated pattern was also detected in nitrogen-deficient physic nut [26]. In this study, NR expression showed a reducing trend related to nitrogen concentration, showing a similar regulation pattern in A. fistulosum.

Several works on the correlation between gene expression and the biosynthesis of amino acids under nitrogen supplementation conditions have been conducted on Arabidopsis [27], rice [28], and tea [19]. In this study, we identified 1,665 DEGs in the pseudostems of Welsh onion in response to different concentrations of nitrogen. These DEGs provided candidate genes for further analysis of biological function and pathways regarding nitrogen transportation and metabolism. GO enrichment analysis efficiently predicted the biological functions according to the transcriptome data [29]. Multiple GO terms were significantly represented under different levels of nitrogen treatment, especially those for amino acid and peptide biosynthesis, metabolism, and transporters. Moreover, KEGG analysis showed that a substantial number of DEGs were detected under nitrogen starvation and led to significant changes in some metabolic pathways, including amino acid metabolism, translation, carbohydrate metabolism, and biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites. Our previous results indicated that the highest phenolic content was observed in the N2 treatment group, whereas that in the N0 group was the lowest [30]. This can be attributed to the DEGs identified in the pathways of metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides between nitrogen-free and full levels of nitrogen treatment (Table 6).

The results revealed that the pseudostems of the Welsh onion, after nitrogen treatment, contained significantly more threonine and proline than the nitrogen-free group, while a higher content of cysteine and arginine were detected in the nitrogen-free samples. Cysteine and glutathione metabolism are reported to indicate parallels with Allium flavour precursor biosynthesis [31]. Moreover, cysteine is the first organic product generated from S [32]. Cysteine synthase is the last enzyme of sulfate assimilation pathway, and O-acetylserine (OAS), the precursor of cysteine, is derived from the carbon and nitrogen assimilation pathways [33]. The down-regulated pattern of CS was detected after nitrogen treatment. For one hand, the synthesis of cysteine decreased; for another, with the precursor of cysteine, flavour compounds were synthesized. The results indicated that nitrogen supply affect sulphur assimilation pathways, including the synthesis of cysteine and other products, thus affacting the flavour of Welsh onion. Ornithine is the point of entry for the biosynthesis of polyamines such as putrescine, spermidine, and spermine, which are used to store excess organic nitrogen in plant tissues [34]. Arginine is the precursor of ornithine, and this was probably the reason why the arginine content was reduced after nitrogen treatment (Fig. 4). The alpha-enolase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase genes were also up-regulated. These are key enzyme genes related to glycolysis, and the catalytic products are the main precursors of amino acids. The number of precursors may determine the difference between the content of amino acids. It seems that nitrogen treatment might also promote glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) flux as well as amino acid metabolism. Our previous results showed that the highest yields were detected in the full levels of nitrogen treatment (N2) followed by half-levels of nitrogen (N1) [35]. Therefore, it is possible that nitrogen triggers a number of molecular and physiological events that lead to the increase of plant biomass, especially for carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism.

In the glutamine–glutamate cycle, GOGAT, GS, and GDH were the key enzymes regulating the amount of each compound. Glutamate was always used as the nitrogen source in the biosynthesis of nitrogen compounds [19]. Under nitrogen starvation, the transcript levels of GS and GOGAT were up-regulated, whereas GDH was found to be significantly down-regulated (Fig. 2). We also measured the metabolites of the glutamine–glutamate cycle and found that the glutamate content did not significantly change after treatment with different concentrations of nitrogen. It can be assumed that the higher expression level of the two genes with nitrogen treatment was induced by urea-derived ammonium through a positive feedback mechanism via the GS–GOGAT cycle.

Conclusions

This work examined the influence of nitrogen in the activation of nitrogen-related genes and amino acid metabolism in Welsh onion for the first time. The transcriptome analysis of Welsh onion on different concentrations of nitrogen treatment revealed that 1,665 genes were significantly regulated. GO analysis revealed that the DEGs were associated with diverse processes. The metabolism and transporters of various amino acids were highly represented, indicating the processes involved with using nitrogen. KEGG analysis provided the enrichment pathways related to amino acid metabolism. However, the DEGs’ response to nitrogen application resulted in different contents of amino acids. With the introduction of the effect of nitrogen in gene expression and amino acid synthesis, this work provides important evidence of NUE in Welsh onion.

Methods

Plant materials and RNA extraction

The A. fistulosum species was obtained from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Planting was performed as previously described [35], and seedlings were grown under field conditions in Zhangqiu district, Jinan city, Shandong Province, China. The soil type was classified as cinnamon soil and had a nitrogen concentration of 80.67 mg kg−1 before the experiment. The plants were treated with three different concentrations of urea, namely, nitrogen-free (without urea), half levels of nitrogen (130 kg ha−1), and full levels of nitrogen (260 kg ha−1). The treatments (0 N, half N, full N) were named N0, N1, and N2. The seedlings were grown in 15 independent plots, with five plots for each nitrogen concentration. The fertilizer was used four times during the growth stages of Welsh onion, on June 25, August 14, August 27, and September 9, 2017, respectively. Welsh onion was collected on October 1, 2017, and further analyses were performed. Of the five field plot replications, two plot replications were randomly selected for each group to make biological replications for RNA extraction. Randomly selected samples of pseudostems in the same plot were pooled together, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C. Total RNA was extracted from the pseudostems using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) following the manufacturers’ instructions. RNA quality was determined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Transcriptome sequencing

For each treatment, three micrograms of RNA of the tissues with different concentrations of nitrogen were used to obtain the cDNA libraries. Sequencing libraries were generated using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). To select the preferred cDNA fragments that were 200 bp in length, the library fragments were purified using the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, CA, USA). DNA fragments with ligated adaptor molecules on both ends were selectively enriched with an Illumina PCR Primer Cocktail in a 15-cycle polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction. The 150 bp paired-end cDNA libraries were sequenced on Illumina’s Hiseq 2500 (Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Cp. Ltd.) following standard Illumina methods.

Functional annotation

To obtain high-quality reads, the raw reads were filtrated to remove low-quality reads and reads with adapters. The reads were assembled using Trinity software with default parameters [36, 37]. First, contigs were obtained by extension based on the overlap between sequences. Next, the contigs were joined into transcripts by paired-end mapping. Finally, the contigs were connected to get sequences that could not be extended at either end. The longest transcripts of each gene in the upper genome were extracted as the reference transcript sequence, and cuffcomapare software was used to compare the variable splice sequence of this project with the reference transcript sequence (gff), using ASTALAVISTA software to analyse the variable splicing event. Such sequences were defined as unigenes, which were then aligned with the NR, GO, KEGG, eggNOG, and Swiss-Prot databases.

Differential gene expression and gene enrichment analysis

To analyze differential gene expression, candidate genes were identified with DESeq software [38, 39] in each comparison. Transcripts that exhibited two-fold or above were considered as differentially expressed, and the P-value threshold was set to 0.05. Enrichment patterns were clustered by pheatmap software using a complete linkage method. The unigenes were aligned to the GO and KEGG databases to predict the possible functions and metabolic pathways involved. GO terms were assigned by the Blast2GO program [40]. The KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) was used for pathway annotation. The database searches were performed using BLASTX [41] with a cut-off E-value of 10−5. The enrichment of terms in the different treatments was further analyzed (P < 0.05).

Amino acids detection

The samples for the analysis of amino acids were the same as those used in transcriptome sequencing. The pseudostem samples (0.5 g) with three biological replicates were treated with 5 mL of 10 % acetic acid and grinding on ice. The extractions were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The filtered liquid was collected to enable amino acid detection. All of the extracted filtrates were filtered through 0.45 μm membranes before being measured. Amino acids were quantified using an amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, L-8900, Japan) with standard methods. Statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro to evaluate the statistical significance of differences between different culture conditions. Analysis was conducted with three technical replicates, and error bars (± SEM) were shown for independent experiments. Significances were calculated using an ANOVA approach, and the Tukey test was applied to determine differences between treated and untreated samples. P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Availability of data and materials

RNA-seq raw data were deposited in the SRA database of NCBI with accession number PRJNA504406.

Abbreviations

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- NUE:

-

nitrogen use efficiency

- RNA-sec:

-

Ribonucleic acid-sequencing

- GOGAT:

-

glutamate synthase

- GS:

-

glutamine synthetase

- DEG:

-

differentially expressed gene

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- KEGG:

-

the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- eggNOG:

-

evolutionary genealogy of genes:Non-supervised Orthologous Groups

- NR:

-

nitrate reductase

- AsuS:

-

argininosuccinate synthase

- ASL:

-

argininosuccinate lyase

- GDH:

-

glutamate dehydrogenase

- AMT:

-

ammonium transporter

- TCA:

-

tricarboxylic acid cycle

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- KAAS:

-

KEGG Automatic Annotation Server

References

Frink CR, Waggoner PE, Ausubel JH. Nitrogen fertilizer: retrospect and prospect. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(4):1175–80.

Horchani F, Prévot M, Boscari A, Evangelisti E, Meilhoc E, Bruand C, et al. Both plant and bacterial nitrate reductases contribute to nitric oxide production in Medicago truncatula nitrogen-fixing nodules. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(2):1023–36.

Laura Z, Silvia V, Nicola T, Anita Z, De BFRM, Zeno V, et al. Short-Term treatment with the urease inhibitor N-(n-Butyl) thiophosphoric triamide (NBPT) alters urea assimilation and modulates transcriptional profiles of genes involved in primary and secondary metabolism in maize seedlings. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7(62):845.

Dong Y, Cheng Z, Meng H, Liu H, Wu C, Khan AR. The effect of cultivar, sowing date and transplant location in field on bolting of welsh onion (Allium fistulosum L.). Bmc Plant Biol. 2013;13(1):1–12.

Sun XD, Yu XH, Zhou SM, Liu SQ. De novo assembly and characterization of the Welsh onion (Allium fistulosum L.) transcriptome using Illumina technology. Mol Genet Genomics. 2015;291(2):647–59.

Lu S, Li Q, Wei H, Chang MJ, Tunlayaanukit S, Kim H, et al. Ptr-miR397a is a negative regulator of laccase genes affecting lignin content in Populus trichocarpa. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(26):10848–53.

Zhao W, Yang X, Yu H, Jiang W, Sun N, Liu X, et al. RNA-Seq-based transcriptome profiling of early nitrogen deficiency response in cucumber seedlings provides new insight into the putative nitrogen regulatory network. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(3):455–67.

Gegas VC, Nazari A, Griffiths S, Simmonds J, Fish L, Orford S, et al. A genetic framework for grain size and shape variation in wheat. Plant Cell. 2010;22(4):1046–56.

Li A, Liu D, Wu J, Zhao X, Hao M, Geng S, et al. mRNA and small RNA transcriptomes reveal insights into dynamic homoeolog regulation of allopolyploid heterosis in nascent hexaploid wheat. Plant Cell. 2014;26(5):1878–900.

Liu Q, Lan Y, Wen C, Zhao H, Wang J, Wang Y. Transcriptome sequencing analyses between the cytoplasmic male sterile line and its maintainer line in welsh onion (Allium fistulosumL.). Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(7):1058.

Wang R, Okamoto M, Xing X, Crawford N. Microarray analysis of the nitrate response in arabidopsis roots and shoots reveals over 1,000 rapidly responding genes and new linkages to glucose, Trehalose-6-Phosphate, iron, and sulfate metabolism. Plant physiol. 2003;132:556–67.

Scheible WR, Morcuende R, Czechowski T, Fritz C, Osuna D, Palacios-Rojas N, et al. Genome-wide reprogramming of primary and secondary metabolism, protein synthesis, cellular growth processes, and the regulatory infrastructure of Arabidopsis in response to nitrogen. Plant Physiol. 2004;136(1):2483–99.

Sabrina H, Sanjeena S, Jonathan C, Zeng B, Bi YM, Xi C, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of maize in response to individual and combined water and nitrogen stresses. Bmc Genomics. 2013;14(1):3.

Luo J, Zhou J, Li H, Shi W, Polle A, Lu M, et al. Global poplar root and leaf transcriptomes reveal links between growth and stress responses under nitrogen starvation and excess. Tree Physiol. 2015;35(12):1283–302.

Mcallister CH, Beatty PH, Good AG. Engineering nitrogen use efficient crop plants: the current status. Plant Biotechnol J. 2012;10(9):1011–25.

Ruan J, Haerdter R, Gerendás J. Impact of nitrogen supply on carbon/nitrogen allocation: a case study on amino acids and catechins in green tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] plants. Plant Biology. 2010;12(5):724–34.

Zhang Q, Shi Y, Ma L, Yi X, Ruan J. Metabolomic analysis using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF MS) uncovers the effects of light intensity and temperature under shading treatments on the metabolites in tea. Plos One. 2014;9(11):e112572.

Ludewig U, Neuhã¤User B, Dynowski M. Molecular mechanisms of ammonium transport and accumulation in plants. Febs Lett. 2007;581(12):2301–8.

Zhang Q, Liu M, Ruan J. Integrated transcriptome and metabolic analyses reveals novel insights into free amino acid metabolism in Huangjinya tea cultivar. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8.

Zhang X, Liu H, Pilon-Smits E, Huang W, Wang P, Wang M, et al. Transcriptome-Wide Analysis of Nitrogen-Regulated Genes in Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis L. O. Kuntze) and Characterization of Amino Acid Transporter CsCAT9.1. Plants. 2020;9:1218.

Wei W, Qi X, Wang L, Zhang Y, Hua W, Li D, et al. Characterization of the sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) global transcriptome using Illumina paired-end sequencing and development of EST-SSR markers. Bmc Genomics. 2011;12(1):451.

Zhang J, Shan L, Duan J, Jin W, Chen S, Cheng Z, et al. De novo assembly and characterisation of the transcriptome during seed development, and generation of genic-SSR markers in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Bmc Genomics. 2012;13(1):90.

Masclaux-Daubresse C, Chardon F. Exploring nitrogen remobilization for seed filling using natural variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(6):2131–42.

Merigout P, Lelandais M, Bitton F, Renou JP, Briand X, Meyer C, et al. Physiological and transcriptomic aspects of urea uptake and assimilation in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(3):1225–38.

Sinha SK, Sevanthi V AM, Chaudhary S, Tyagi P, Venkadesan S, Rani M, et al. Transcriptome analysis of two rice varieties contrasting for nitrogen use efficiency under chronic N starvation reveals differences in chloroplast and starch metabolism-related genes. Genes. 2018;9(4):206.

Qi K, Zhang S, Wu P, Chen Y, Li M, Jiang H, et al. Global gene expression analysis of the response of physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.) to medium- and long-term nitrogen deficiency. Plos One. 2017;12(8):e0182700.

Balazadeh S, Schildhauer J, Araujo WL, Munne-Bosch S, Fernie AR, Proost S, et al. Reversal of senescence by N resupply to N-starved Arabidopsis thaliana: transcriptomic and metabolomic consequences. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(14):3975–92.

Chandran AKN, Jung K-H. Resources for systems biology in rice. J Plant Biol. 2014;57(2):80–92.

Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(1):1–13.

Zhao C, Wang Z, Cui R, Su L, Sun X, Borras-Hidalgo O, et al. Effects of nitrogen application on phytochemical component levels and anticancer and antioxidant activities of Allium fistulosum. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11706-e.

Jones M, Hughes J, Tregova A, Milne J, Tomsett A, Collin H. Biosynthesis of flavour precursors of onion and garlic. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:1903–18.

Li Q, Gao Y, Yang A. Sulfur Homeostasis in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:8926.

Koprivova A, Suter M, Camp ROD, Brunold C, Kopriva S. Regulation of Sulfate Assimilation by Nitrogen in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:737–46.

Howarth J, Parmar S, Jones J, Shepherd C, Corol D, Galster A, et al. Co-ordinated expression of amino acid metabolism in response to N and S deficiency during wheat grain filling. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:3675–89.

Zhao C, Ni H, Zhao L, Zhou L, Borras-Hidalgo O, Cui R. High nitrogen concentration alter microbial community in Allium fistulosum rhizosphere. Plos One. 2020;15:e0241371.

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–52.

Liu Q, Wen C, Zhao H, Zhang L, Wang J, Wang Y. RNA-Seq reveals leaf cuticular wax-related genes in Welsh onion. Plos one. 2014;9(11):e113290-e.

Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(10):R106.

Wang L, Feng Z, Wang X, Wang X, Zhang X. DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):136–8.

Conesa A, Götz S, Garcíagómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–6.

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–402.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Rongzong Cui, Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, for providing the plant materials.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Key Technologies Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFD0200100), Key Technologies Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (No. 2019QYTPY024, 2018YYSP022, 2019YYSP019, 2018YYSP007, 2018YFJH0404, and 2018CXGC0204), and the Science, Education, and Industry Integration Innovation pilot project at Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences) (No. 2020KJC-GH10).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CZ conducted experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. GM conducted experiments and analyzed data. LZ prepared samples and assayed the contents of amino acids. SZ, LS, and XS analyzed data. OB-H revised the manuscript. KL supported the study. QY and LZ conceived and designed the research and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, C., Ma, G., Zhou, L. et al. Effects of nitrogen levels on gene expression and amino acid metabolism in Welsh onion. BMC Genomics 22, 803 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-08130-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-08130-y