Abstract

Background

Associative transcriptomics has been used extensively in Brassica napus to enable the rapid identification of markers correlated with traits of interest. However, within the important vegetable crop species, Brassica oleracea, the use of associative transcriptomics has been limited due to a lack of fixed genetic resources and the difficulties in generating material due to self-incompatibility. Within Brassica vegetables, the harvestable product can be vegetative or floral tissues and therefore synchronisation of the floral transition is an important goal for growers and breeders. Vernalisation is known to be a key determinant of the floral transition, yet how different vernalisation treatments influence flowering in B. oleracea is not well understood.

Results

Here, we present results from phenotyping a diverse set of 69 B. oleracea accessions for heading and flowering traits under different environmental conditions. We developed a new associative transcriptomics pipeline, and inferred and validated a population structure, for the phenotyped accessions. A genome-wide association study identified miR172D as a candidate for the vernalisation response. Gene expression marker association identified variation in expression of BoFLC.C2 as a further candidate for vernalisation response.

Conclusions

This study describes a new pipeline for performing associative transcriptomics studies in B. oleracea. Using flowering time as an example trait, it provides insights into the genetic basis of vernalisation response in B. oleracea through associative transcriptomics and confirms its characterisation as a complex G x E trait. Candidate leads were identified in miR172D and BoFLC.C2. These results could facilitate marker-based breeding efforts to produce B. oleracea lines with more synchronous heading dates, potentially leading to improved yields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ensuring synchronous transiting from the vegetative to the reproductive phase is important for maximising the harvestable produce from brassica vegetables. Many cultivated brassica vegetables arose from their native wild form B. oleracea var. oleracea [1]. Wild cabbage, B. oleracea L., is a cruciferous perennial growing naturally along the coastlines of Western Europe. From this single species, selective breeding efforts have enabled the production of the numerous subspecies we see today. The specialization of a variety of plant organs has given rise to the large diversity seen within the species. Various parts of brassicas are harvested, including leaves (e.g. leafy-kale and cabbage), stems (e.g. kohl-rabi), and inflorescences (broccoli and cauliflower). For all subspecies, the shift from the vegetative to reproductive phase is important and being able to genetically manipulate this transition will aid the development and production of synchronous brassica vegetables.

Determining how both environmental and genotypic variation affect flowering time is important for unravelling the mechanisms behind this transition. For many B. oleracea varieties, a period of cold exposure, known as vernalisation, is required for the vegetative-to-floral transition to take place. This requirement for vernalisation, or lack thereof, determines whether the plant is a winter annual, perennial or biennial or whether it is rapid-cycling or a summer annual [2]. As a consequence, the response of the plant to vernalisation provides quantifiable variation that has been exploited by breeders to develop varieties with more synchronous heading. Such variation will be key for future breeding in the face of a changing climate.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are an effective means of identifying candidate genes for target traits from panels of genetically diverse lines [3]. GWAS has been used successfully in numerous plant species including Arabidopsis, maize, rice and Brassica [4,5,6,7]. However, its application is reliant on genomic resources which are not always available for complex polyploid crops. Associative transcriptomics uses the sequences of expressed genes (mRNAseq) aligned to a reference to identify and score molecular markers that correlate with trait data. These molecular markers represent variation in gene sequences and expression levels. Therefore, unlike traditional GWAS analysis, associative transcriptomics also enables identification of associations between traits and gene expression levels [4]. Associative transcriptomics is a robust method for identifying significant associations and is being used increasingly to identify molecular markers linked to trait-controlling loci in crops [8,9,10,11].

An important factor to account for in association studies is the genetic linkage between loci. If the frequency of association between the different alleles of a locus is higher or lower than what would be expected if the loci were independent and randomly assorted, then the loci are said to be in linkage disequilibrium (LD) [12]. LD will vary across the genome and across chromosomes and it is important to account for this in GWAS analyses. This variation in LD is due to many factors, including selection, mutation rate and genetic drift. Strong selection or admixture within a population will increase LD. Accounting for the correct population structure reduces the risk of detecting spurious associations within GWAS analyses. The population structure can be determined from unlinked markers [13].

Here, we develop and validate an associative transcriptomics pipeline for B. oleracea. A specific population structure consisting of unlinked markers was generated using SNP data from 69 lines of genetically fixed B. oleracea from the Diversity Fixed Foundation Set [14]. The pipeline was successfully used for the identification of candidate leads involved in vernalisation response, identifying a strong candidate in miR172D.

Results

Exposure to different environmental conditions identifies vernalisation requirements across the phenotyped accessions

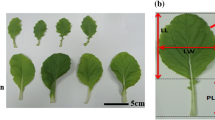

We selected a subset of 69 B. oleracea lines, diverse in both eco-geographic origin and crop type, from the B. oleracea Diversity Fixed Foundation Set [14]. We used these accessions to evaluate the importance of vernalisation parameters by quantifying flowering time under different conditions (vernalisation start, duration and temperature). Two key developmental stages were monitored: ‘days to buds visible’ (DTB) and ‘days to first flower’ (DTF). The variation in flowering time across the different treatments and between the different lines is shown in Fig. 1. The different vernalisation start times demonstrate that exposure to the longer, ten-week pre-vernalisation growth period (10WPG) typically results in earlier flowering, compared to the shorter, six-week pre-growth period (6WPG). The mean DTB for 6WPG was 21.0 days (SD = 51.6), compared to 5.8 days (SD = 49.9) for the 10WPG (Wilcoxon Test, W = 17,958, P = 0.004). Similarly, we found a significant difference in the time taken to reach DTF between the two treatment groups, with a mean of 57.9 days (SD = 55.5) following the 6WPG, in comparison to 35.9 days (SD = 53.1) following the 10WPG (Wilcoxon Test, W = 17,471, P = 2.96e-05).

Flowering time traits exhibit a varied response to different environmental conditions within the population. Examples of opposing phenotypic response to different vernalisation temperatures can be observed in (A) Brussels Sprout, Cavolo Di Bruxelles Precoce (GT120168) and (B) Broccoli, Mar DH (GT110244). Variation across the population for (C) DTB post vernalisation per treatment, per line. (D) DTF post vernalisation per treatment, per line. Day 0 represents the end of vernalisation, negative values represent heading or flowering during the pre-growth or vernalisation

Changes in vernalisation duration led to a significant difference in DTB, but not in DTF. Following the six-week vernalisation (6WV), the mean DTB was 9.5 days (SD = 44.5) compared to 5.8 days (SD = 46.8) after exposure to twelve-weeks of vernalisation (12WV) (Wilcoxon Test, W = 19,532, P = 0.002). This difference was coupled with more synchronous heading between lines following the 12WV period. The impact of vernalisation duration on DTB varied across the population, reflecting the numerous factors that can affect DTB depending on crop type, such as stem elongation and developmental arrest.

Of the three parameters we investigated, vernalisation temperature resulted in the most pronounced phenotypic differences. The 5ºC vernalisation (5 ºCV) resulted in the largest DTB (slowest overall bud development), whereas the 10ºC vernalisation (10 ºCV) treatment resulted in the largest DTF. The distribution between heading dates was distinctly different between the temperatures. Higher vernalisation temperatures resulted in larger the variation in DTB and DTF. The more synchronous heading and flowering for the 5ºCV treatment suggests that this temperature was able to saturate the vernalisation requirement for a large proportion of the lines. After exposure to the warmer temperatures, the variation in DTB and DTF were greatly increased (Additional File 1), indicating that the cooler vernalisation temperature aided faster transitioning in some lines, but delayed the development of others. This is consistent with differences in B. oleracea crop types, for example Brussels Sprouts are known to have a strong vernalisation requirement, whereas Summer Cauliflower have been bred to produce curd rapidly without the need for cold exposure [15, 16].

The effect of vernalisation temperature on the floral transition is demonstrated clearly between the Broccoli Mar DH and the Brussel Sprout Cavolo Di Bruxelles Precoce (Fig. 1 A), with polar responses to vernalisation temperature. Mar DH transitioned fastest under the 15 ºC vernalisation (15 ºCV) treatment, whereas Cavolo Di Bruxelles Precoce transitioned faster under the 5 ºCV treatment. Faster transitions at higher vernalisation temperatures as in the case of Mar DH, however, can lead to undesirable phenotypes from a grower’s perspective (Fig. 1B).

Unlinked markers are required to generate a representative population structure

GWAS requires trait, SNP and population data. The correct population structure is important for ensuring that associations are with the trait of interest rather than identified on account of relatedness within the population, in particular for panels of only one species. To generate a representative population structure, it is necessary to ensure the SNPs used are unlinked [13]. However, different criteria have been used to select these SNPs [6, 17,18,19]. To evaluate the impact of SNP selection criteria, we generated two population structures and investigated their suitability for representing the panel.

Using all markers with a minor allele frequency (MAF) larger than 0.05 [4, 20, 21], reduced the total number of SNPs from 110,555 to 36,631. Calculation of ΔK showed a maximum value of K = 2, although a further peak in ΔK was observed at K = 5 (Additional File 6 A), thus identifying substructure within the population. ΔK frequently identifies K = 2 as the top level of hierarchical structure, even when more subpopulations are present [21, 22]. Subsequent phylogenetic analysis (Additional File 7 A, 7B) identified clusters representing these sub populations. Therefore, to account for substructure within the population, the value of K = 5 was used for further analysis [22, 23]. A second population structure was generated using stricter parameters, requiring the markers be biallelic, MAF > 0.05, one per gene and at least 500 bp apart. A total of 664 SNPs met these requirements, resulting in the identification of four subpopulation clusters (Additional File 4).

We assessed the two population structures based on crop type and phenotypic data. Using K = 5, generated using the less stringent parameters, (Fig. 2 A, 2 C, 2E) cluster one contained only broccoli and calabrese, both members of the same subspecies var. italica [24, 25], whereas cluster two mainly comprised cauliflower, subspecies var. botrytis. Late flowering accessions were included in both clusters. Interestingly, this population structure grouped the rapid cycling and late flowering kales together with a spread of accessions from other crop types, in cluster four. The remaining two clusters were small by comparison: cluster three comprised of seven accessions, a mixture of broccoli, cauliflower and kale; cluster five consisted of just two lines, one kale and one cauliflower.

The choice of SNP pruning rules can significantly change the inferred population structure. Density plots representing (A) DTB, (C) DTF for the accessions within the five subpopulation clusters. Density plots representing (B) DTB, (D) DTF for the accessions within the four subpopulation clusters. E Population structure generated from SNPs with MAF > 0.05. F Population structure generated from more stringent SNP pruning (Biallelic only, MAF > 0.05, > 500-bp apart, one per gene)

The four clusters identified using more stringent SNP selection criteria contained all of the rapid cycling kales in cluster one, characterised by their early heading and flowering phenotypes (Fig. 2B and D F). This was identified as a clear subgroup within the phylogenetic tree (Additional File 7 C). Cluster two was mainly broccoli and calabrese, whilst cluster three consisted largely of the earlier flowering cauliflowers. Cluster four contained the late flowering individuals from all crop types within the population, hence the larger variation in heading and flowering for this cluster.

Comparison of the clustering of accessions between the two population structures demonstrated the more stringent SNP criteria gave rise to a population structure in which individuals were grouped with other accessions that would be expected to be genetically similar based on knowledge of crop type and flowering phenotype. Consequently, this population structure was applied in subsequent GWAS analyses.

To gauge the extent of linkage disequilibrium we calculated the mean pairwise squared allele-frequency correlation (r2) for mapped markers. A linkage disequilibrium window of 50 (providing > 3 million pairwise values of r2) resulted in a mean pairwise r2 of 0.0979, confirming a low overall level of linkage disequilibrium in B. oleracea.

Associative transcriptomics identifies miR172D as a candidate for controlling vernalisation response

SNP associations were compared to the physical positions of orthologues of genes known to be involved in the floral transition in Arabidopsis. A total of 43 flowering time related traits (Additional File 2) were analysed using this pipeline, including DTB and DTF for each treatment. A total of 111 significant SNPs were identified, P < 0.05, six of which demonstrated clear association peaks and were investigated further (Table 1).

We first sought to identify genetic associations with the trait data for the non-vernalised experiment. Whilst no significant association peaks were identified for DTB, a single marker association at Bo8g089990.1:453:T was identified (P = 2.29E-06) for DTF under non-vernalising conditions. This marker was within a region demonstrating good synteny to Arabidopsis, despite there being a number of unannotated gene models present. Conservation between Arabidopsis and B. oleracea suggests that this region contains an orthologue of microRNA172D, AT3G55512, which has been linked to the floral transition in A. thaliana [26, 27] (Fig. 3 A). Furthermore, the difference in DTB between 10WPG6WV5 ºCV and 10WPG12WV15 ºCV, identified a significant association on C07 at Bo7g104810.1:204:T (FDR, P < 0.05). This association was in the vicinity of a second orthologue of miR172D (Fig. 3 C).

The developed pipeline identifies associations with flowering traits. Distribution of mapped markers associating with (A) Number of DTF under non-vernalising conditions (B) DTB after a six-week pre-growth, twelve weeks vernalisation 10 ºC (C) The difference in DTB between six and twelve weeks of vernalisation at 15 ºC, after exposure to a ten-week pre-growth (D) The DTF after exposure to six-week pre-growth, twelve weeks vernalisation 10 ºC. Sixty-nine accessions of B. oleracea were phenotyped for DTB and DTF and marker associations were calculated using a generalized linear model, implemented in TASSEL to incorporate population structure. Log10 (P values) were plotted against the nine B. oleracea chromosomes in SNP order. Blue line FDR threshold, P < 0.05, FDR threshold was not met for A) and D)

We then analysed the association with traits relating to the timing of vernalisation. No significant associations were identified for traits after 6WPG12WV5 ºCV. However, a strong association was identified on C07 at the marker Bo7g026810.1:124:G, for DTF for 6WPG12WV10 ºCV. Synteny with Arabidopsis suggests that an orthologue of FRI INTERACTING PROTEIN 1, (FIP1), AT2G06005.1 (Fig. 3D) is present within this region. Within Arabidopsis it has been demonstrated that FIP1 interacts with FRIGIDA (FRI) [28] which is a major source of natural variation in flowering time in Arabidopsis and has been shown to be important in determining vernalisation requirement. Additionally, significant associations (FDR, P < 0.05), were found for DTB for 6WPG12WV10 ºCV. An association was identified at Bo9g179000.1:2589:G, which is in the vicinity of an orthologue of EARLY FLOWERING 6 (ELF6), AT5G04240.1 (Fig. 3B), a nuclear targeted protein able to affect flowering time irrespective of FLC.

The differences in flowering phenotype between the SNP variants for the four strongest associations were analysed (Fig. 4). There were significant differences in the traits associated with miR172D (DTF with no vernalisation and the difference in DTB for plants grown under 5 ºCV and 15 ºCV) for different alleles (Fig. 4 A and B). For Bo7g104810.1:204:T (difference in DTB after exposure to 5 ºCV and 15 ºCV), five individuals, four broccoli and one cauliflower, contained the A variant. The alternate variant, a T allele, and was present in 50 individuals. Conversely, Bo8g089990.1:453:T (DTF with no vernalisation) had 11 individuals with a C allele at this locus, whilst 51 had a T allele. Interestingly, individuals with the C allele were present in every crop type.

A significant phenotypic difference was found for individuals exhibiting SNP variants for the associations pointing to miR172D as a candidate. Boxplots represent the trait data, DTB or DTF for each of the significant markers alongside the different alleles present across the population for each marker. The box represents interquartile range, outliers are represented by black dots

Associative transcriptomics identifies Bo FLC.C2 as a candidate gene involved in vernalisation requirement in B. oleracea

An advantage of performing associative transcriptomics as opposed to GWAS, is the additional ability to identify associations between gene expression and the trait of interest. GWAS analysis identified an association of the difference between DTB and DTF with a 10WPG6WV5 ºCV with a candidate marker in the well characterized flowering time gene, BoFLC.C2 (Table 1). Using gene expression marker (GEM) analysis, BoFLC.C2 expression was also identified as being significantly associated with both the DTB and DTF under non-vernalising conditions (Fig. 5). BoFLC.C2 exhibited both low and high expression within the population. As expected, all five rapid cycling accessions demonstrated no BoFLC.C2 expression. Recently, a Brassica consortium developed targeted sequence capture for a set of relevant genes, including FLC. DNA from four of the five rapid cycling accessions had been enriched with that capture library and sequenced. Lacking a reference sequence for B. oleracea that contains BoFLC.C2, we used B. napus (cv. Darmor) [29] as a reference to map the captured sequence data from the four rapid cycling accessions to. Comparison of B. oleracea transcript data [30] to this Darmor genome reference revealed a 99.54 % identity in coding sequence, allowing Darmor to be used as a surrogate reference. Indeed, we found that BoFLC.C2 was absent from all four rapid cycling accessions, GT050381, GT080767, GT100067 and GT110222, revealed by a lack of read mapping (Additional File 10). BoFLC.C2 is known to be involved in vernalisation response [30] and rapid cycling varieties do not require a period of vernalisation in order to transition to the floral state. As a control, we investigated mapping for 49 non-rapid cycling accessions where we expect BoFLC.C2 to be present. For all 49 we found the expected read mapping evidence, confirming that use of the polyploid B. napus reference is appropriate (Additional File 10). The control of flowering is a complex, multigenic trait, therefore we would not expect a single locus to explain all variation across the entire dataset. Indeed, only a weak positive correlation (DTB R2 = 0.024, DTF R2 = 0.036) between flowering phenotype and BoFLC.C2 expression was identified. A strong positive correlation (DTB R2 = 0.871, DTF R2 = 0.891) was found for the phenotypic extremes (rapid cycling lines with no expression and the late flowering lines with high levels of BoFLC.C2), Fig. 6, confirming a role for BoFLC.C2.

GEM analysis identifies FLC expression on chromosome C2 as a candidate for flowering traits under non-vernalising conditions. Distribution of gene expression markers associating with (A) DTB after exposure to non-vernalising conditions (B) DTF after exposure to non-vernalising conditions. Log10 (P values) were plotted against the nine B. oleracea chromosomes in SNP order. Blue line FDR threshold, P < 0.05

Discussion

Determining which genes underly phenotypic traits is a key step for crop improvement. A powerful approach for identifying candidates is associative transcriptomics, which has been implemented for several crops. However, for the important vegetable crop B. oleracea, no such pipeline has been published to date. Here we present a validated associative transcriptomics pipeline for B. oleracea and use it to identify gene candidates for vernalisation.

To reduce the risk of false positives, we developed stringent criteria to identify unlinked markers for the determination of the population structure. The population structure was validated using crop type and phenotypic information on heading and flowering, this example was chosen as producing synchronous B. oleracea vegetables is a key goal for growers and breeders. Quantifying vernalisation responses for different varieties is an important step towards this goal, providing a foundation for targeted breeding.

Phenotyping for both DTB and DTF under different environmental conditions revealed a varied response within the population and identified some general trends. Altering the timing of vernalisation demonstrated that a shorter growth period prior to the exposure to cold extended the time taken to reach DTB and DTF. This could be attributed to the presence of a juvenile phase in many of the lines, which has been widely documented in B. oleracea [14, 31, 32]. A juvenile plant is described as being unable to respond to floral inductive cues. The fact that many lines were able to flower much faster following longer pre-vernalisation growth, suggests they had reached the adult vegetative phase and were receptive to cold as a floral inductive cue. Further experimental work would be needed to test this hypothesis.

Increasing vernalisation length and reducing vernalisation temperature resulted, on average, in faster and more synchronous heading and flowering. This was a predicted outcome, as current knowledge suggests that increased vernalisation duration and cooler vernalisation temperatures would saturate the vernalisation requirement of a larger proportion of accessions.

Using our validated population structure with associative mapping, we identified candidates orthologous to known Arabidopsis floral regulators, including miR172D. In Arabidopsis, the miR172 family post-transcriptionally supress a number of APETALA1-like genes, including TARGET OF EAT1, 2 and 3, which in turn aids the promotion of floral induction [27, 33,34,35]. Furthermore, the SNP variant data for both associations implicating miR172D, exhibit significant phenotypic differences. Two orthologues of Arabidopsis miR172D have been identified in B. oleracea [36] but their functional roles have yet to be determined.

GWAS analysis identified a significant association with BoFLC.C2 and the difference in DTB and DTF following a ten-week pre-growth period, with six weeks of vernalisation at 5 ºC. BoFLC.C2 is a well characterized flowering time gene [30] and the ability of the GWAS pipeline to identify a known candidate gives confidence in the method. Furthermore, GEM analysis identified BoFLC.C2 expression as being significantly associated with both DTB and DTF under non-vernalising conditions, which can be attributed to the extreme phenotypes within the population (Fig. 6). No BoFLC.C2 expression was detected in five lines. A loss-of-function mutation at BoFLC.C2 in cauliflower has been associated with an early flowering phenotype [37], indicating that BoFLC.C2 has an equivalent role in cauliflower to FLC in Arabidopsis. Four of the five lines for which BoFLC.C2 expression could not be detected did not have the BoFLC.C2 paralogue according to the bait capture sequencing data. These four lines were all kales and demonstrated an early flowering phenotype, suggesting that BoFLC.C2 has a similar role to AtFLC in kales, and potentially across B. oleracea. Although DTB and DTF were highly correlated with BoFLC.C2 expression under non-vernalising conditions for the phenotypic extremes, for the whole population the correlation was low. This is to be expected as BoFLC.C2 is just one of many genes that we expect to be involved in the floral transition within B. oleracea and therefore is unlikely to account for all the observed variation.

The expression data used for the GEM analysis was generated from leaf tissue at one timepoint. As a consequence, any genes which are not expressed in the leaf at this time will not be identified in this analysis. Use of transcriptome data from other tissues in addition to the leaf data could identify a greater number of associations.

Conclusions

Identifying genes underlying phenotypic traits in B. oleracea is an important step for the improvement of brassica vegetables. Here, we generate and validate a novel pipeline for associative transcriptomics analysis in B. oleracea and show that this pipeline is effective in identifying genetic regulators of complex traits, such as flowering time, demonstrating this approach can be utilised for other traits of agronomic importance, such as germination, quality traits and disease resistance. GWAS analysis identified miR172D as a candidate for vernalisation response, whilst GWAS and GEM analysis identified a significant marker at BoFLC.C2, an important gene in the vernalisation pathway of B. oleracea. Our results provide insight into the genetic control of flowering in B. oleracea, and candidates which could provide a foundation for future breeding strategies.

Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

A subset of 69 lines fixed as doubled haploids (DH) or at S4 and above were chosen from the Brassica oleracea Diversity Fixed Foundation Set [14] (Additional File 1) comprising accessions from seven different B. oleracea crop types; cabbage, cauliflower, calabrese, broccoli, kohl rabi, kale and Brussels sprout. Plants were grown in cereals mix (40 % Medium Grade Peat, 40 % Sterilised Soil, 20 % Horticultural Grit, 1.3 kg/m³ PG Mix 14-16-18 + Te Base Fertiliser, 1 kg/m³ Osmocote Mini 16-8-11 2 mg + Te 0.02 % B, Wetting Agent, 3 kg/m³ Maglime, 300 g/m³ Exemptor) and given a pre-growth period of either six or ten weeks in a glasshouse under natural light supplemented with LED lighting (16 h daylength 21/18 °C day/night). At the end of the pre-growth period, three plants of each line for each treatments were transferred to Conviron controlled environment rooms for six or twelve weeks vernalisation at 5, 10 or 15 ºC (16 h daylength LED, 60 % humidity). Following vernalisation, plants were re-potted into 2 L pots and placed into a polytunnel under natural light using a randomised block design. All plants came out of vernalisation and into the polytunnel on the same day due to staggered sowing to control for post-vernalisation environmental conditions. Three replicates of each line were grown without vernalisation as a non-vernalised control group. The plants were scored at buds visible (DTB) and upon opening of first flower (DTF) [38]. A summary of pre-growth and vernalisation conditions and traits analysed is given in Additional File 2.

SNP Calling

The growth conditions, sampling of plant material, RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing was carried out as described by He et al. [39]. The RNA-seq data from each accession were mapped on to CDS models from the Brassica oleracea pangenome [40] as reference sequences, using Maq v0.7.1 [41]. SNPs were called by the meta-analysis of alignments as described in Bancroft et al. [42]. SNP positions were excluded if they had a read depth < 10, a base call quality < Q20, missing data > 0.25, and > 3 alleles. This resulted in a SNP file containing 110,555 SNPS, and 65,017 unigene sequences with associated RPKM values.

Population Structure and GWAS analyses

Population structure was generated using both relaxed (all markers with a minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05) and stringent criteria using STRUCTURE [43] (burn-in10000, MCMC 10,000, 10 iterations). For the stringent criteria, SNPs were required to be biallelic, with a minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05 and a minimum distance of 500-bp between markers. STRUCTURE HARVESTER [44] was used to determine the optimal K value. The Q matrix used in GWAS analysis was calculated using CLUMPP [45].

TASSEL [46] version 5.0 was used to select the most appropriate model for each trait based on QQ plots. Generalised linear models (GLM), with correction for population structure using the Q matrix or PCA (5 PCs) were used to look for associations. For GWAS analysis only SNP markers with an allele frequency > 0.05 were used. To gauge the extent of linkage disequilibrium, the mean pairwise r2 was calculated using the SlidingWindow function within TASSEL, with a linkage disequilibrium window of 50. TASSEL was used to construct phylogenetic trees, using the Neighbour Joining method and all SNPs with MAF > 0.05. Trees were graphed in R using the package ggtree [47].

Gene expression marker (GEM) associations were calculated by an in-house script in R Version 3.6.3 using a fixed effect linear model with RPKM values, excluding markers with an average expression below 0.5 RPKM. Linear regression was performed using RPKM as a predictor value to predict a quantitative outcome of the trait value. Both SNP and GEM outputs were plotted as Manhattan Plots created using an in-house R script. All scripts are available at https://github.com/JIC-CSB/Boleracea-AssociativeTranscriptomics. Statistical significance for both GWAS and GEM association was determined by the false discovery rate (FDR) [48] calculated using the QValue package [49] in R.

DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA of accessions used in bait capture sequencing was prepared from young leaf tissue of plants grown in a glasshouse (16 h LED supplementary light, 21/18 °C day/night). Light was excluded for 48 h prior to harvesting. Nuclei were extracted from ~ 3 g of tissue prior to CTAB based DNA extraction. Extracts were treated with RNase T1, RNaseA and Proteinase K to remove RNA and protein contamination, respectively. DNA was resuspended in 50 µl dH2O and checked for quality. DNA was quantified by and stored at -20 °C.

Targeted Sequence Enrichment analysis

A bait library for targeted sequence enrichment for a specific subset of genes was developed and synthesized with Arbor Biosciences (https://arborbiosci.com/). Samples were 4 plexed and run on the NovaSeq S4, PE150, 1Gbp/library. Reads from individual accessions were mapped to the reference sequence of B. napus cv. Darmor-bzh [29] using BWA [50] version 0.7.17-r1188 using aln/sampe and standard parameters. Mapped reads were sorted and indexed using SAMTOOLS [51] version 1.10 sort and index, and subsequently visualized with Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) [52].

Availability of data and materials

Sequence data from this article can be found in the SRA data library under accession number PRJNA309368, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA309368. The R scripts used to carry out GEM analysis and to generate the corresponding Manhattan plots for both GEM and GWAS analysis are available on GitHub in the JIC_CSB/Boleracea-AssociativeTranscriptomics repository, DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4529809 [53]. Raw data for targeted sequence capture experiments has been deposited at EBI, under study number PRJEB43076, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB43076, and the bait library is available at DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4473283 [54].

References

Wichmann MC, Alexander MJ, Hails RS, Bullock JM. Historical distribution and regional dynamics of two Brassica species. Ecography (Cop). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008;31:673–84.

Chouard P. Vernalization and its Relations to Dormancy. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. Annual Reviews 4139 El Camino Way, P.O. Box 10139, Palo Alto, CA 94303-0139, USA; 1960;11:191–238.

Korte A, Farlow A. The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: a review. Plant methods. 2013;9(1):1-9.

Harper AL, Trick M, Higgins J, Fraser F, Clissold L, Wells R, et al. Associative transcriptomics of traits in the polyploid crop species Brassica napus. Nat Biotechnol. Nature Publishing Group; 2012;30:798–802.

Huang X, Zhao Y, Wei X, Li C, Wang A, Zhao Q, et al. Genome-wide association study of flowering time and grain yield traits in a worldwide collection of rice germplasm. Nat Genet. Nature Publishing Group; 2012;44:32–9.

Raman H, Raman R, Qiu Y, Yadav AS, Sureshkumar S, Borg L, et al. GWAS hints at pleiotropic roles for FLOWERING LOCUS T in flowering time and yield-related traits in canola. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):1-8.

Romero Navarro JA, Willcox M, Burgueño J, Romay C, Swarts K, Trachsel S, et al. A study of allelic diversity underlying flowering-time adaptation in maize landraces. Nat Genet. 2017;49:476–80.

Miller CN, Harper AL, Trick M, Werner P, Waldron K, Bancroft I. Elucidation of the genetic basis of variation for stem strength characteristics in bread wheat by Associative Transcriptomics. BMC Genomics. BioMed Central; 2016;17:500.

Zhao K, Tung CW, Eizenga GC, Wright MH, Ali ML, Price AH, et al. Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat Commun. Nature Publishing Group; 2011;2:467.

Cockram J, White J, Zuluaga DL, Smith D, Comadran J, MacAulay M, et al. Genome-wide association mapping to candidate polymorphism resolution in the unsequenced barley genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. National Academy of Sciences; 2010;107:21611–6.

Yu J, Buckler ES. Genetic association mapping and genome organization of maize. Curr Opin Biotechnol. Elsevier Current Trends; 2006;17:155–60.

Flint-Garcia SA, Thornsberry JM, Buckler ES. Structure of Linkage Disequilibrium in Plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:357–74.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005;14:2611–20.

Walley PG, Teakle GR, Moore JD, Allender CJ, Pink DA, Buchanan-Wollaston V, et al. Developing genetic resources for pre-breeding in Brassica oleracea L.: An overview of the UK perspective. J Plant Biotechnol. 2012;39:62-8.

Putterill J, Laurie R, Macknight R. It’s time to flower: the genetic control of flowering time. BioEssays. Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company; 2004;26:363–73.

Rosen A, Hasan Y, Briggs W, Uptmoor R. Genome-Based Prediction of Time to Curd Induction in Cauliflower. Front Plant Sci. Frontiers; 2018;9:78.

Xu L, Hu K, Zhang Z, Guan C, Chen S, Hua W, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals the genetic architecture of flowering time in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). DNA Res. Oxford Academic; 2015;23:43–52.

Chen J, Zheng H, Bei J-X, Sun L, Jia W, Li T, et al. Genetic Structure of the Han Chinese Population Revealed by Genome-wide SNP Variation. Am J Hum Genet. Cell Press; 2009;85:775–85.

Breria CM, Hsieh CH, Yen J-Y, Nair R, Lin C-Y, Huang S-M, et al. Population Structure of the World Vegetable Center Mungbean Mini Core Collection and Genome-Wide Association Mapping of Loci Associated with Variation of Seed Coat Luster. Trop Plant Biol. Springer; 2020;13:1–12.

Lu G, Harper AL, Trick M, Morgan C, Fraser F, O’Neill C, et al. Associative transcriptomics study dissects the genetic architecture of seed glucosinolate content in brassica napus. DNA Res. Narnia; 2014;21:613–25.

Prom LK, Ahn · Ezekiel, Thomas Isakeit ·, Magill · Clint. GWAS analysis of sorghum association panel lines identifies SNPs associated with disease response to Texas isolates of Colletotrichum sublineola. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132:1389–96.

Cullingham CI, Miller JM, Peery RM, Dupuis JR, Malenfant RM, Gorrell JC, et al. Confidently identifying the correct K value using the ∆K method: When does K = 2? Mol Ecol. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2020;29:862–9.

Janes JK, Miller JM, Dupuis JR, Malenfant RM, Gorrell JC, Cullingham CI, et al. The K = 2 conundrum. Mol Ecol. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2017;26:3594–602.

Labana KS, Gupta ML. Importance and Origin. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 1993:1–7.

Maggioni L, von Bothmer R, Poulsen G, Branca F. Origin and domestication of cole crops (Brassica oleracea L.): Linguistic and literary considerations. Econ Bot. Springer; 2010;64:109–23.

Poethig RS. Small RNAs and developmental timing in plants. Curr Opin Genet Dev. Elsevier Current Trends; 2009;19:374–8.

Aukerman MJ, Sakai H. The Plant Cell Regulation of Flowering Time and Floral Organ Identity by a MicroRNA and Its APETALA2-Like Target Genes. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2730–41.

Geraldo N, Bäurle I, Kidou SI, Hu X, Dean C. FRIGIDA delays flowering in Arabidopsis via a cotranscriptional mechanism involving direct interaction with the nuclear cap-binding complex. Plant Physiol. American Society of Plant Biologists; 2009;150:1611–8.

Chalhoub B, Denoeud F, Liu S, Parkin IAP, Tang H, Wang X, et al. Erratum: Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 2014;345:950-3

Irwin JA, Soumpourou E, Lister C, Ligthart JD, Kennedy S, Dean C. Nucleotide polymorphism affecting FLC expression underpins heading date variation in horticultural brassicas. Plant J. 2016;87:597–605.

Wurr DCE, Fellows JR, Sutherland RA, Elphinstone ED. A model of cauliflower curd growth to predict when curds reach a specified size. J Hortic Sci. Taylor & Francis; 2016;65:555–64.

Hand DJ, Atherton JG. Curd initiation in the cauliflower: I. Juvenility. J Exp Bot. Narnia; 1987;38:2050–8.

Teotia S, Tang G. To bloom or not to bloom: Role of micrornas in plant flowering. Mol Plant. 2015;8:359-77.

Jung J-H, Seo Y-H, Seo PJ, Reyes JL, Yun J, Chua N-H, et al. The GIGANTEA-Regulated MicroRNA172 Mediates Photoperiodic Flowering Independent of CONSTANS in Arabidopsis W OA.

Wu G, Park MY, Conway SR, Wang J-W, Weigel D, Poethig RS. The Sequential Action of miR156 and miR172 Regulates Developmental Timing in Arabidopsis. Cell. Cell Press; 2009;138:750–9.

Shivaraj S, Dhakate P, Mayee P, Negi M, Singh A. Natural genetic variation in MIR172 isolated from Brassica species. Biol Plant. 2014;58:627–40.

Ridge S, Brown PH, Hecht V, Driessen RG, Weller JL. The role of BoFLC2 in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L.) reproductive development. J Exp Bot. Oxford University Press; 2015;66:125–35.

Meier U. Growth stages of mono-and dicotyledonous plants BBCH Monograph Federal Biological Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry. Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag; 1997.

He Z, Wang L, Harper AL, Havlickova L, Pradhan AK, Parkin IAP, et al. Extensive homoeologous genome exchanges in allopolyploid crops revealed by mRNAseq-based visualization. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15:594-604.

Golicz AA, Bayer PE, Barker GC, Edger PP, Kim HR, Martinez PA, et al. The pangenome of an agronomically important crop plant Brassica oleracea. Nat Commun. Nature Publishing Group; 2016;7:13390.

Li H, Ruan J, Durbin R. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008;18:1851-8.

Bancroft I, Morgan C, Fraser F, Higgins J, Wells R, Clissold L, et al. Dissecting the genome of the polyploid crop oilseed rape by transcriptome sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. Nature Publishing Group; 2011;29:762–6.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Earl DA, vonHoldt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. Springer; 2012;4:359–61.

Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA. Genetics and population analysis CLUMPP: a cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. 2007;23:1801–6.

Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. Oxford Academic; 2007;23:2633–5.

Yu G, Smith DK, Zhu H, Guan Y, Lam TTY. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol Evol. British Ecological Society; 2017;8:28–36.

Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. False discovery rate–adjusted multiple confidence intervals for selected parameters. J Am Stat Assoc. 2005;100(469):71-81.

Storey J, Bass A, Dabney A, Robinson D. Qvalue [Internet]. qvalue Q-value Estim. false Discov. rate Control. R Packag. version 2.18.0. 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available from: http://github.com/jdstorey/qvalue

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. Oxford University Press; 2009;25:1754–60.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. Oxford Academic; 2009;25:2078–9.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. NIH Public Access; 2011;29:24–6.

Woodhouse S. JIC-CSB/Boleracea-AssociativeTranscriptomics: Brassica oleracea Associative Transcriptomics [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Feb 12]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/4529809#.YCZ9ry2l1ao

Steuernagel B, Woodhouse S, He Z, Hepworth J, Tidy A, Siles-Suarez L, et al. BRAVO target sequence capture V3 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Feb 12]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/4473283#.YCZ91S2l1ap

Acknowledgements

We thank Profs Lars Ostergaard and Steve Penfield (JIC) and Drs Andrea Harper and Lenka Havlickova (York) for discussion and critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr Alex Calderwood (JIC) for guidance and advice. We also thank University of Warwick Germplasm Resources Unit for use of the B. oleracea Diversity Fixed Foundation Set [14].

Funding

SW was supported by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) NRPDTP PhD Studentship Programme. JI and RW acknowledge funding from BBSRC Institute Strategic Programme (BB/P013511/1), RM, JI and RW acknowledge support from the BBSRC sLoLa ‘Brassica Rapeseed and Vegetable Optimisation’ (BB/P003095/1) and IB and ZH acknowledge funding from BBSRC (BB/L002124/1). RM acknowledges support from EU-Horizon2020 ERC Synergy Grant ‘PLAMORF’ (ID: 810131). Additional funding was provided by BBSRC sLoLa ‘Renewable Industrial Products from Rapeseed’(BB/L002124/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JI, RM, RW and SW designed the experiments that were carried out by SW with support from JI and RW. The SNP calling was carried out by ZH under guidance of IB. SW performed the phenotyping of material, all analyses and produced all figures. RW, IB and WH provided genomics and bioinformatics advice. HW provided programming support and guidance. BS designed and constructed the bait library for targeted sequence enrichment and carried out subsequent sequence mapping, which was analysed by SW. SW drafted the manuscript which was planned and refined by SW, RW and all authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The plant material within this paper was obtained under material transfer agreement (MTA) from Warwick Germplasm Research Unit (GRU), part of the European Cooperative Program for Plant Genetic Resources (ECPFR). As such, it complies with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. The appropriate permissions and/or licences for collection of plant or seed specimens have been observed by Warwick GRU for their collections and by the authors under MTA for their subsequent use.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Details of phenotyped panel, with associated crop type, subspecies and EcoTILLING information.

Additional file 2:

List of conditions and traits run through the associative transcriptomics pipeline.

Additional file 3:

Phenotyping results, mean DTB and DTF under all treatments tested.

Additional file 4:

Analysis of the smaller SNP data set with the Bayesian clustering algorithms implemented in the program STRUCTURE, identified four population clusters.

Additional file 5:

Increased synchrony in DTB and DTF was observed as vernalisation temperature was reduced. Histograms representing the distribution of DTB and DTF post-vernalisation across the population after exposure to vernalization at 5, 10 or 15 oC. Individuals that did not flower have been removed from this plot.

Additional file 6:

ΔK based on rate of change of LnP, Maxima indicates the ΔK that best explains the population structure. Plots produced using STRUCTURE Harvester output. A) ΔK values for biallelic SNPs, MAF > 0.05, one SNP per gene, >500kb apart, K = 4. B) ΔK values calculated for SNPs with MAF > 0.05, K = 5.

Additional file 7:

Phylogenetic trees, generated in TASSEL using the Neighbour Joining method, to demonstrate the substructure present within the phenotyped panel. A) K = 2, the highest level of structure seen within the population following analysis with the relaxed SNP set, B) K = 5, the substructure present within the population following analysis with the relaxed SNP set. C) K = 4, the result following population structure analysis on the stringent SNP set.

Additional file 8:

Quantile-Quantile Plots for SNP associations with A) the DTF under NV conditions. GLM, with Q matrix correction for population structure B) the DTB after six-week pre-growth and 10ºC vernalisation for twelve-weeks. GLM, with Q matrix correction for population structure C) The difference in DTB following 5 ºC and 15 ºC vernalisation for six-weeks, after exposure to a ten-week pre-growth. GLM with Q matrix correction for population structure D) The DTF after exposure to six-week pre-growth, twelve weeks vernalisation 10 ºC. GLM with PCA correction for population structure.

Additional file 9:

Linkage disequilibrium decay. A) Bo8g089990.1:453:T, miR172D candidate. B) Bo9g179000.1:2589:G, ELF6 candidate. C) Bo7g026810.1:124:G, FIP1 candidate. D) Bo7g104810.1:204:T, miR172D candidate.

Additional file 10:

Mapping BoFLC.C2 using Darmor-bzh as a reference. Four rapid cycling accessions and three representative accessions for the rest of the population.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Woodhouse, S., He, Z., Woolfenden, H. et al. Validation of a novel associative transcriptomics pipeline in Brassica oleracea: identifying candidates for vernalisation response. BMC Genomics 22, 539 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07805-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07805-w