Abstract

Background

Theileria orientalis (Apicomplexa: Piroplasmida) has caused clinical disease in cattle of Eastern Asia for many years and its recent rapid spread throughout Australian and New Zealand herds has caused substantial economic losses to production through cattle deaths, late term abortion and morbidity. Disease outbreaks have been linked to the detection of a pathogenic genotype of T. orientalis, genotype Ikeda, which is also responsible for disease outbreaks in Asia. Here, we sequenced and compared the draft genomes of one pathogenic (Ikeda) and two apathogenic (Chitose, Buffeli) isolates of T. orientalis sourced from Australian herds.

Results

Using de novo assembled sequences and a single nucleotide variant (SNV) analysis pipeline, we found extensive genetic divergence between the T. orientalis genotypes. A genome-wide phylogeny reconstructed to address continued confusion over nomenclature of this species displayed concordance with prior phylogenetic studies based on the major piroplasm surface protein (MPSP) gene. However, average nucleotide identity (ANI) values revealed that the divergence between isolates is comparable to that observed between other theilerias which represent distinct species. Analysis of SNVs revealed putative recombination between the Chitose and Buffeli genotypes and also between Australian and Japanese Ikeda isolates. Finally, to inform future vaccine studies, dN/dS ratios and surface location predictions were analysed. Six predicted surface protein targets were confirmed to be expressed during the piroplasm phase of the parasite by mass spectrometry.

Conclusions

We used whole genome sequencing to demonstrate that the T. orientalis Ikeda, Chitose and Buffeli variants show substantial genetic divergence. Our data indicates that future researchers could potentially consider disease-associated Ikeda and closely related genotypes as a separate species from non-pathogenic Chitose and Buffeli.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Theileria orientalis is a tick-borne parasite that has caused outbreaks of clinical theileriosis in cattle in Japan, Korea and China [1]. Recently, outbreaks of disease have been reported in Australia and New Zealand where the disease has spread rapidly causing substantial economic losses to cattle production [2]. Theileria species display similar morphology [3] and, historically, species delineations have been made based on differences in location, pathogenicity, vector competency and host-pathogen interactions [4,5,6]. T. orientalis was previously split into a three-species complex (T. sergenti/buffeli/orientalis), however, more recently the organism is generally classified in the literature as one species (T. orientalis) [1, 7, 8]. This recognition has been based on more recent molecular examinations of phylogeny, which have largely focused on individual genes, such as those encoding immunogenic piroplasm surface proteins. Sequence variability in the major piroplasm surface protein (MPSP) has been used to classify the organism into 11 distinct genotypes [1, 7, 8]. Pathogenicity is associated with Type 2 (Ikeda) while other types, such as the widespread Types 1 and 3 (Chitose and Buffeli, respectively), have largely been linked to benign infections [9,10,11].

The genetic diversity of apicomplexan parasites allows for rapid adaptation to selective pressures, which has significant consequences for vaccine design and the development of drug resistance. Moreover, the highly diverse surfaceomes of these populations allow for the avoidance of specific immune responses thereby limiting pathogen clearance [12]. The development of inexpensive whole genome sequencing technologies that allow for direct sequencing of clinically-derived samples promises to revolutionize the study of parasitic diversity. Additionally, large scale monitoring of genetic variations in field samples can provide critical information for disease surveillance [13]. Furthermore, the study of diverse apicomplexan surfaceomes has the potential to improve the design of subunit vaccines, which currently have limited effectiveness [14].

To date, a single T. orientalis genome, that of the Japanese Shintoku strain (genotype Ikeda), has been genome sequenced via the Sanger method. That study revealed a 9 Mb, 4 chromosome nuclear genome structure, as well as mitochondrial and apicoplast genomes [15], a karyotype that appears to be conserved within the Theileria genus [16,17,18]. However, no current studies have focused on whole genome phylogenies of the T. orientalis genotypes. In the present study, we used comparative genomics to examine three Australian isolates of T. orientalis, namely Robertson (Ikeda), Fish Creek (Chitose) and Goon Nure (Buffeli), using Illumina technology and identified extensive genetic differences between these genotypes.

Results

Reference genome read mapping and de novo assembly

For each isolate, reads from three technical replicate sequencing experiments were aligned to the Shintoku reference genome (Assembly ASM74089v1) and merged to generate a single file. The Shintoku reference sequence is of the Ikeda genotype and hence the Robertson strain showed high proportions of reads mapped, reference sequence coverage and depth of sequence coverage (Table 1). Fish Creek [19] and Goon Nure isolates showed reduced percentages of mapped reads and reference coverage, indicating a high amount of sequence divergence from Ikeda. However, alignments of assembled sequences show coverage of a high proportion of the T. orientalis Shintoku genome sequence (Additional files 1 & 2). Bos taurus host DNA was detected at low levels and represented less than 1.35% of reads for all isolates. Genome assemblies produced varied results with the Robertson assembly producing longer and fewer total contigs. In contrast, assemblies of the Fish Creek and Goon Nure isolates were more fragmented (Table 1). To investigate the reason for this contrast we examined haplotype diversity to indicate if an increased in the number of quasi-species were present in the Goon Nure and Fish Creek isolates. Sequencing reads from each isolate were examined by mapping back to the assemblies and variant calling to identify biallelic SNVs. Goon Nure showed a much higher number of biallelic SNVs (27947) vs Fish Creek (4634) and Robertson (1669) indicating that assembly fragmentation is potentially caused by greater haplotype diversity and quasi-species in the Goon Nure isolate. The assembly pipeline used, A5-miseq, was designed to assemble haploid genomes of clonal, axenically-cultured microbes. When substantial genomic polymorphism is likely to be present in the data, the pipeline produces an assembly that is fragmented, with contig boundaries occurring frequently at polymorphic sites.

SNV validation and analysis

Variation between the three isolates examined in this study was relatively high, reflecting the diversity of this parasite. Moreover, many contigs from the Fish Creek and Goon Nure genome assemblies did not align to the Shintoku reference, or other isolates from this study (Additional file 1). BLAST searches of these contigs using the NCBI non-redundant database produce no significant hits. Novel sequence and differences in gene content are discussed in more detail below.

In this study, in-depth variant analysis of all isolates was limited to SNV mutations due to reported difficulties in the analysis of indel mutations using short read alignment methods [20]. To assess isolate variation, reads were aligned to the Shintoku reference sequence and homozygous SNVs called (Table 2). To examine the effectiveness of this methodology in detecting SNV variants, we examined false discovery using simulated alignments. Simulated alignments with higher divergence to those observed between the Shintoku reference and Fish Creek/Goon Nure reads (~ 900,000 substitution events, ~ 90,000 insertion-deletion events) produced a false discovery rate of 1.8%. Variant detection was also examined with Sanger sequencing of representative sections from each genome (Additional file 3). Very high sensitivity values were observed in the Robertson isolate (Additional file 3). No false positive calls (Illumina positive/Sanger negative) were observed in any isolate, while false negative calls were very low in Robertson, but increased in Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains. When false negative calls were examined in depth it was found that all were closely associated with observed small insertion or deletion events, which have been previously reported to be problematic in SNV calling pipelines [20].

When comparing variation between genotypes, the Robertson isolate showed expectedly high similarity to the Shintoku reference sequence, while Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains showed similar levels of divergence (Table 2). Total numbers of variants were similar in the Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains, however, these variants were largely found in differing positions reflecting the divergence between all three isolates. Coding sequences showed a higher variant density than non-coding sequences (Table 2), but this is likely a consequence of greater coding sequence coverage (Table 1). In validation experiments with simulated reads and Sanger sequencing, we noticed that in sequence regions with a high number of short indel mutations read mapping coverage was reduced. These high indel regions seem to be more common in the non-coding genome and result in reduced coverage. Excepting chromosomal ends where sequencing coverage was low, variants were evenly distributed in Fish Creek and Goon Nure sequences (Additional file 4). Some high variation regions were identified in the Robertson sequence and these areas largely correspond to hypothetical genes (Additional files 4 & 5).

Ortholog clustering and novel gene prescence

To explore differences in gene content between the four genomes, we examined predicted proteins using OrthoFinder [21]. Using an evidence-based annotation methodology for eukaryotic genomes, we identified 3675, 3624 and 4789 genes in the Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains, compared with 4002 genes identified in the Shintoku genome sequence. Ortholog clustering identified that the higher gene content detected in the Goon Nure sequence is due to a higher number of genes unassigned to orthologous groups shared by the four genomes (515 vs 59–114) and a higher amount of gene duplication, which is demonstrated by increased number of orthogroups with multiple genes from Goon Nure compared to Robertson/Chitose (Additional file 6). This increase is present when OrthoFinder is run with an increased similarity threshold (e-value = 1e-100), indicating higher gene copy number could be produced by haplotype diversity as outlined above or by gene duplication within the Goon Nure genome. To examine this further we mapped sequencing reads to predicted coding sequences for each isolate with bowtie2, using the -k 1 option so that each read was only aligned once. We then examined if there was a stoichiometric-like relationship between average gene coverage and the per-isolate number of genes in an orthogroup. If duplication of genes was caused by the generation of highly similar quasi-species contigs during the assembly process, then orthogroups with higher numbers of genes per-isolate should show lower coverage in stoichiometric-like ratios. Robertson and Fish Creek showed relatively stable coverage regardless of per-isolate orthogroup gene number (Additional file 7). For Goon Nure, average gene coverage was higher in orthogroups with lower numbers of genes but differences were less than expected for a stoichiometric-like ratio, indicating that increased genome duplication or other reasons may contribute to the fragmentation observed.

To identify unique genes present within Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains we first examined the similarity of predicted proteins to those identified from the Shintoku whole genome sequence using blastp, as this method would identify proteins that were both present in each genome and also predicted by each annotation pipeline. A total of 29, 32 and 69 predicted coding sequences from Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains respectively did not show similarity (e-value cutoff 1e-5) to any predicted protein sequence from the T. orientalis Shintoku genome.

Predicted protein coding sequences that did not match Shintoku predicted proteins were examined further with tblastn to determine if they were present within the Shintoku genome sequence and identify if differences in gene content were due to mutations, annotation pipline differences, pseudogenes or inserted/deleted coding sequences. For strains Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure a respective 28, 19 and 22 zero-hit blastp putative proteins matched regions of the Shintoku genome with tblastn. This resulted in a respective total of 1, 13 and 39 coding sequences from Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains did not show similarity (e-value cutoff 1e-5) to the translated Shintoku genome sequence with either blastp or tblastn. Of the zero-hit blastp putative proteins that matched with tblastn 20 (Robertson), 8 (Fish Creek) and 11 (Goon Nure) matched intergenic regions of the Shintoku genome. A further 8, 10 and 10 predicted proteins of the respective Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure genome sequences matched annotations in regions of hypothetical proteins in the Shintoku sequence, but predicted a protein in a different translational frame. Finally, one predicted hypothetical protein from both the Fish Creek and Goon Nure isolates matched the opposite strand of a proteasome component (XP_009692024.1) gene. Further inspection of this proteasome component revealed it is truncated by four C-terminal exons in Fish Creek and Goon Nure when compared to Shintoku and Robertson. However, this truncation is consistant with other piroplasmid species (T. parva, T. annulate, B. microti and B. bigemina) which are of comparable length to the predicted Fish Creek and Goon Nure proteasome component.

Zero-hit blastp putative proteins were also compared to the non-redundant protein database with BLAST (accessed 29–1-2017) to identify if any were homologous to proteins from other species. A total of 8, 7 and 10 of these putative proteins from the Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure isolates respectively showed similarity to those found in the non-redundant database. These included a conserved apicomplexan specific protein (all isolates), a putative exonuclease (all isolates) and a RNA methyl-transferase (Robertson, Fish Creek). Results of blastp searches of the nr database are shown in Additional file 8.

Recombination analysis

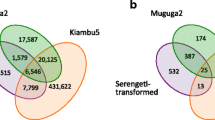

Potential for recombination between T. orientalis genotypes has previously been postulated [1, 22]. To explore this, we examined the T. orientalis SNV datasets for recombination events as previously done with Theileria parva [23]. The frequencies of all 7 possible genotype combinations are shown as a Venn diagram (Fig. 1) and show high values for Fish Creek and Goon Nure containing combinations and low numbers for Robertson combinations, which reflect the genetic distance between these genotypes and the Shintoku reference. When these allele combinations were graphed against their genomic loci, little evidence of SNV clustering associated with recombination events could be observed (data not shown), potentially due to the high number of variant positions present. To further examine potential recombination, six recombination detection tests, namely Geneconv, MaxChi, Recombination Detection Program (RDP), BootScan, 3Seq and SiScan were used to analyse SNV-derived alignments. A total of 83 potential recombination events were detected in the concatenated SNV dataset (Fig. 2; detail in Additional file 9). All detected events were relatively small, with genomic sizes ranging 3–13,821 bp in size and a median of 989 bp. Furthermore, no evidence of recombination was detected between the Ikeda genotype samples (Robertson/Shintoku) and Chitose (Fish Creek) or Buffeli (Goon Nure) genotypes.

Recombination analysis of T. orientalis Shintoku, Ikeda, Chitose and Buffeli genotypes. In total, 83 recombination events were detected using six recombination prediction methods (Geneconv, MaxChi, RDP, SisScan, 3Seq and BootScan). Shintoku, Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure chromosomes (grey) are shown aligned with probable major parent sequences shown as coloured lines. Most likely major parent sources are shown by colour (see legend)

Mitochondrial genomes of Ikeda, Chitose and Buffeli isolates

Theileria mitochondrial genomes have been previously observed to be linear and relatively small at approximately 6 kbp in size [24]. In T. orientalis isolates that were examined in this study (Fig. 3), we were able to confirm a linear structure with inverted PCR utilizing outward facing primers at the edge of each mitochondrial genome. Furthermore, some Babesia mitochondrial genomes have been described to undergo multiple inversions [25]. To determine if this occurs in T. orientalis mitochondrial genomes, we examined sequencing reads mapped to assembled Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure mitochondrial genomes for evidence of split-reads, i.e. reads partially mapped to the contig and soft-clipped. We found no evidence of soft-clipped reads indicative of an inversion event in any of the three T. orientalis mitochondrial sequences.

dN/dS analysis

Analysis of the dN/dS ratio has the potential to inform future vaccine studies due to the link between high dN/dS and antigenic potential [23, 26]. In this study, we examined the dN/dS ratio calculated using reconstructed genomes generated from the Shintoku reference sequence and homozygous SNVs from the Fish Creek and Goon Nure genome sequences. The Robertson isolate was determined to be too closely related to the reference sequence (3377/4002 genes with < 5 mutations) and was excluded from this analysis, however, Robertson coding sequences with high numbers of variants were observed and the number of mutations per coding sequence are listed in Additional file 5. The dN/dS ratios of 3577/4002 and 3230/4002 genes were examined from Fish Creek and Goon Nure sequences (Additional file 10), while the dN/dS of predicted surface proteins (SignalP and TMHMM positive) are shown in Table 3. These dN/dS values compare well with similar studies in other Theileria species [23]. To further examine surface proteins of T. orientalis we examined extracts of purified piroplasms with mass spectrometry and were able to confirm the expression of 6 of these proteins. These included 2 hypothetical proteins (XP_009690040.1, XP_009690016.1), surface antigens MPSP (XP_009689845.1) and p23 (XP_009690580.1), a bifunctional nuclease (XP_009691620.1) and transmembrane protein 17 (XP_009690633.1).

MLST phylogeny of Ikeda, Chitose and Buffeli and their place within the Piroplasmida

To assess if whole genome sequences could be used to further refine the taxonomy of T. orientalis, we explored two commonly used methods of species definition, phylogeny and average nucleotide identity (ANI), using T. orientalis whole genome assemblies and representative whole genome sequences of the Order Piroplasmida (Fig. 4). Support values based on bootstrap analysis show very high support for all branches. Both whole genome phylogeny and ANI reveal a very close relationship between Shintoku and Robertson genomes. In contrast, ANIs between strains Robertson/Shintoku and Fish Creek/Goon Nure are low for organisms considered to be of the same species and compare well with those observed between T. parva and T. annulata (Fig. 4b). ANI clustering was also used to compare species of the Plasmodium genus (Additional file 11). For comparison, murine species Plasmodium berghei, Plasmodium yoelii, Plasmodium vinckei, and Plasmodium chabaudi have pairwise ANI that range from 83.5–90.1%.

a. Multilocus phylogeny of Piroplasmida whole genome sequences. The tree was inferred by maximum-likelihood using an alignment of 654 concatenated protein sequences from single copy genes. Plasmodium falciparum str. 3D7 was included as an outgroup. Labels indicated bootstrap support (%). b. Average nucleotide identities between genomes of the Theileria genus as calculated by the method described in [92]

Discussion

This study presents the first genomic analysis of Australian isolates of T. orientalis and the first published genomic sequences of Chitose and Buffeli types. Genomic studies allow for multi-locus strategies to define evolutionary relationships with greater confidence than those that rely on single genes. In the Order Piroplasmida, the placement of species such as Theileria equi and Babesia microti, has been greatly clarified using these techniques [17, 27]. The taxonomy of T. orientalis has been controversial [28] and originally T. orientalis, T. sergenti and T. buffeli were all used, in a regionally-specific manner, to describe this organism. Researchers in early molecular studies that originally attempted to identify differences that could separate morphologically indistinguishable T. orientalis, T. sergenti and T. buffeli instead determined that these “species” consisted of multiple common genotypes that often had little correlation with these definitions [29,30,31]. The result of these has led to the general use of T. orientalis in the literature to describe this group with differences in MPSP used to define 11 recognized genotypes [1, 7, 8]. However, the organism is often referred to as T. sergenti, T. buffeli, and the T. orientalis/buffeli group and hence its taxonomy requires further clarification [32,33,34].

Examination of the relationship between Shintoku/Robertson (Ikeda), Fish Creek (Chitose) and Goon Nure (Buffeli) isolates using the multi-locus strategy in this study reveals a similar structure to previous phylogenies [22, 29]. These phylogenetic analyses based on MPSP consistently show a clear separation between Chitose/Buffeli sequences, which cluster with Types 4, 5, 8 and N3, and Ikeda, which clusters with Type 7 [1, 8, 22, 35, 36]. Furthermore, Chitose/Buffeli and Ikeda isolates had comparable ANIs to T. parva and T. annulata (Fig. 4b). Moreover, prediction of recombination in these isolates identified putative recombinant/major parent pairings within Shintoku/Robertson and Fish Creek/Goon Nure isolates but not between these groups. Alpha-taxonomy continues to be an area of uncertainty in protists as no generally accepted basis for delimiting species exists. Instead, species designations are determined on a case-by-case basis and based on a combination of observed phenotypic and genotypic evidence [37], with pathogenicity considered a key phenotypic delineator [38]. Based on the genotypic differences observed here, previous MPSP-based phylogenetic studies and observations of pathogenicity of the Ikeda genotype [9,10,11, 22, 39, 40], disease-associated Ikeda and closely related Type 7 could potentially be considered a separate species from non-pathogenic Chitose, Buffeli and related Types 4, 5, 8 and N3. Furthermore, the genomic divergence observed between Chitose and Buffeli isolates (86.5%) compare well to the ANI range of murine Plasmodium spp. (83.5–90.1%), indicating that a subspecies classification may also be appropriate for these organisms. Future studies focusing on the genomics of Types 4–8 and N1–3 as well as globally distributed isolates of Ikeda, Chitose and Buffeli would help resolve further confusion surrounding the taxonomy of this organism.

Previous studies have hypothesized that recombination between T. orientalis genotypes is unlikely [1]. Other studies have observed mosaic sequences in the T. orientalis group are potentially indicative of recombination, however, these sequences could also be products of cloned PCR chimeras [22, 41]. In Theileria parva sourced from cattle, recombination has been identified using statistical analysis of concatenated SNV alignments [23]. However, recombination was not detected between cattle- and buffalo-sourced sequences. Furthermore, these statistical techniques are potentially susceptible to false positives. Using these methods, we have detected evidence of recombination in short sequences between Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains and, to a lesser extent, between the Shintoku and Robertson strains. This is particularly notable as the Fish Creek and Goon Nure sequences have a much lower average nucleotide identity than the T. parva sequence group. Hayashida et al. postulate that the lack of observed recombination between cattle and buffalo T. parva is likely caused by isolation due to host adaptation [23]. Such isolation is not observed in T. orientalis isolates studied here, which are all cattle-adapted and prevalent in Eastern Asia and Australia [11, 22]. Identification of recombination limits in Theileria will require further comparative genomics of globally distributed genotypes.

Identification of T. orientalis Ikeda in Australian herds was confirmed in 2006 and it has since become endemic to the south-east, closely matching the distribution of the recognized vector Haemaphyalis longicornis [42]. The original source of T. orientalis Ikeda infections in Australia has been difficult to identify. In response to outbreaks of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, the importation of live cattle from Japan was banned in 2001. However, prior to this, Japanese-sourced, live Wagyu cattle were reportedly imported into Australia via the USA [43] to establish the Wagyu genetic line for breeding purposes, and if these imports occurred they could have been a source of introduction. An alternative source of introduction could be migratory birds. Several bird species migrate to Australia from north-eastern Asia during the northern hemisphere winter and H. longicornis has been found on migratory birds from these areas [44]. While infection of birds with T. orientalis is unlikely, they may play a role in the transport of infected ticks to new areas [45]. Additionally, the potential for transstadial transmission may provide a mechanism for birds to transport tick-borne apicomplexan parasites over long distances [46].

High dN/dS predicted surface proteins that diverged greatly between the pathogenic and apathogenic species included multiple uncharacterized and hypothetical proteins, 7 of which are unique to T. orientalis. The Frequently Associated In Theileria (FAINT) domain (Pf04385) shows high representation in these proteins as indicated previously [15]. Other noteworthy proteins include homologs to antigen Tp2, identified in T. parva as an immunodominant T-cell antigen [47]; thrombospondin-related anonymous protein, recognized as an adhesin in several Plasmodium and Babesia species [48,49,50,51,52]; and MPSP and P23 surface proteins, which are highly expressed surface antigens in T. orientalis that have been shown to bind heparin and, in the case of the MPSP, also shown to bind bovine erythrocytes [53, 54]. Partial protection and reduced clinical symptoms have been demonstrated using subunit vaccines generated from whole or immunogenic portions of the MPSP sequence [30]. Further vaccine studies using data from this study (Table 3) may inform strategies for future Theileria disease outbreaks.

Methods

Samples

Samples were sourced from cattle testing PCR positive for a single T. orientalis genotype based on the major piroplasm surface protein sequence (ie. Ikeda, Chitose or Buffeli) and were collected by private or district veterinarians as part of routine clinical monitoring. The isolates were sourced from cattle in Robertson, New South Wales (Collected 2009, breed: Angus), Fish Creek in Southern Victoria (Collected 2014, breed: Friesian) and Goon Nure in East Gippsland, Victoria (Collected 2012, breed: Freisian) respectively and named according to their location of isolation. Confirmation that each isolate was of a single genotype was performed with two separate PCR assays [10, 40]. Two to three days following the initial bleed, approximately 80 mL of blood was collected into anticoagulant (heparin or citrate) and shipped to a laboratory cold for propagation (1 passage) and extraction. On arrival samples were mixed with cryopreservative and stored as stabilates at − 80 °C until required.

Propagation and purification of Theileria piroplasms

This research was carried out in accordance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes at the Tick Fever Centre, Wacol, Queensland. To propagate Theileria piroplasms, individual splenectomised calves were inoculated with stabilate generated from Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure strains. Blood samples were drawn from each calf at regular intervals to monitor the infection and Giemsa-stained blood smears were used to estimate the level of parasitaemia. The packed cell volume (PCV) was also monitored. When parasitaemia had reached an appropriate level (6–20%), approximately 3.5 L of calf blood was collected into anticoagulant (CPDA1 or heparin). The blood was transferred into 300–500 mL blood bags using a dialysis pump and subsequently passed through Terumo leukocyte filters (300 mL blood per filter) under gravity. Leukocyte-depleted blood was then transferred to centrifuge tubes, centrifuged at 2500×g for 20 min and the serum and any remaining buffy coat removed. The remaining erythrocytes were washed 3 × with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS) followed by centrifugation as described above and diluted 5 × with D-PBS and loaded into a cell disruption vessel (“nitrogen bomb”). The erythrocytes were lysed and the parasite harvested by differential centrifugation as described previously [55]. Briefly, the vessel was infused with nitrogen gas to a pressure of 1000 psi for 1 min and then the pressure was released. The lysed erythrocytes were collected into a clean vessel and then transferred to centrifuge tubes. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 670×g for 10 min to pellet the red blood cell debris. The supernatant was then harvested and centrifuged at 2700×g for 10 min to pellet the piroplasms. The piroplasms were resuspended in D-PBS and a smear prepared from the suspension, which was stained with Giemsa stain to check purity. The piroplasms were then aliquoted into microfuge tubes and centrifuged at 2700×g for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and the piroplasm pellets stored at − 80 °C. Piroplasm preparations were transferred on dry ice and maintained at − 80 °C thereafter.

Nucleic acid extraction and whole genome sequencing

Piroplasm pellets were resuspended in 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline and DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each sample, tagmentation of genomic DNA, and PCR amplification of tagged DNA were performed in triplicate using the Nextera system (Illumina). Sequencing libraries were pooled and normalized using bead size selection (SPRI beads, Beckman Coulter). The Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, with the High Sensitivity DNA kit was used to quantitate the pooled library before loading onto the Illumina platforms (Miseq or HiSeq). Paired-end 250 nt reads were generated using MiSeq V2 chemistry and paired-end 150 nt reads were generated using the HiSeq2500 system.

Protein extraction, electrophoresis and mass spectrometry

From approximately 0.1 g of T. orientalis Ikeda (Robertson strain) pelleted piroplasms, proteins were extracted, enriched, excised from 1-D sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and prepared for mass spectrometry as previously described [56]. Briefly, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, stained, excised from the gel lane and separated into 16 slices. Each gel slice was then diced into ~ 1 mm cubes, stripped of dye, washed and digested in-gel with trypsin for analysis. Protein identification was performed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using a QSTAR Elite hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (AB Sciex). MS/MS data files were analysed using Mascot (provided by the Australian Proteomics Computational Facility, hosted by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research Systems Biology Mascot Server) against the non-redundant MSPnr100 database compiled from all known reference protein sequences including NCBI, Refseq, UniProt, EuPathDB and Ensembl. Peptides matches at p < 0.05 (Ion score > 60) were classified as hits.

Assembly and annotation

Genome assembly was achieved with raw reads using the A5-miseq (v2015–05-22) pipeline [57]. Levels of remaining host DNA were assessed and filtered using BioBloomTools [58] and the B. taurus genome sequence [59]. Whole genome alignments were performed using progressiveMauve from Mauve v2.4.0 and nucmer from MUMmer v3.23 [60, 61]. For analysis of gene presence/absence, genes were annotated using Maker v3.00 beta [62] to combine the annotation tracks derived from expressed sequence tag (EST) and protein alignments and ab initio gene predictors. Firstly, repeat regions of the Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure strain genome assemblies were masked using RepeatMasker v4.0.7. With repeat masked sequences, ab initio annotation tracks were derived from gene predictors Augustus v3.2.3 [63], Snap v2013–11-29 [64], and GeneMark ES Suite v4.32 [65] utilizing both GeneMark ET (Robertson and Fish Creek), and GeneMark ES (Goon Nure). A training set based on EST alignments (RNA data sourced from the Shintoku WGS project [15]) and transcoding regions was generated by PASA v2.1.0 [66] and used to train all ab initio predictors except GeneMark ES. Alignment of EST and protein evidence was performed with Exonerate v2.2.0 [67] using the coding2genome and protein2genome models respectively. Maker was run using the trained gene predictors and performed EST and protein alignments. Following annotation each independent gene track was assessed using Evidence Modeler v1.1.1 [66] to generate the final annotation with the following weights applied (EST: coding2genome = 7, blastn = 2, tblastx = 2. Protein: protein2genome = 10, blastx = 2. Ab initio: augustus = 2, snap = 1, genemark = 1). Additionally, annotations were manually curated by visual inspection and comparison to those transferred by RATT [68] for further quality checking. All parameter files used by Maker and Evidence Modeler to generate each annotation are included as Additional files 12, 13 and 14. Functional annotation was performed with Blast2GO v4.1.9 [69]. Predicted protein sequences were examined with blastp-fast (e-value cutoff 1e-5) against a local version of the non-redundant protein database (downloaded 2017–07-01). From blastp results, a gene ontology (GO) annotation was generated and extended through merging with results from InterProScan [70]. Finally, GO annotations were extended with ANNEX [71].

Ortholog clustering and gene presence analysis

Ortholog clustering of translated proteins from annotated draft genomes was performed with Orthofinder v2.1.2 [21] using 10 whole genome sequences from species representing the Piroplasmida order and one outgroup species Plasmodium falciparum strain 3D7. The 10 genomes include the three T. orientalis isolates examined in this study and previously published and annotated whole genome sequences of T. orientalis¸ Theileria parva, Theileria annulata, Theileria (formerly Babesia) equi, Babesia bovis, Babesia bigemina and Babesia microti [15,16,17,18, 27, 72,73,74]. For characterisation of the presence of T. orientalis genes in sequences generated by this study and absence in the Shintoku genome sequence, translated Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure proteins were scanned against translated T. orientalis Shintoku proteins using blastp (e-value cutoff 1e-5). Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure proteins that did not match any T. orientalis Shintoku proteins were further examined using tblastn (e-value cutoff 1e-5) of the T. orientalis Shintoku genome sequence. All proteins that did not match Shintoku sequences were further examined using blastp and the non-redundant protein database (2018–01–30).

Variant calling and validation

For variant calling, reads were first trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.33 based on leading and trailing base quality (Q < 20) and a 4-base sliding window when average quality scores were less than 20 [75]. Read quality was assessed pre- and post-trimming with FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and sequence files were manipulated using ngs-utils v0.5.7 [76]. For between population variants, trimmed reads were mapped to the T. orientalis Shintoku reference sequence [15] with NextGenMap v0.4.12 [77]. Low quality mapped reads (Q < 10) were filtered using samtools v1.2 [78] and alignments were subsequently sorted, and duplicates removed using picard tools v1.138 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Variant calling was performed using VarScan v2.3.8 [20] on mpileup files generated by samtools. Variant calling parameters were based on previous studies into apicomplexan SNV detection and variant calling algorithm comparisons [79, 80]. Specifically, variants were called using a minimum coverage of 14 × [79], minimum average quality of 20, minimum variant supporting reads of 4, minimum variant frequency of 0.01 and minimum p-value threshold of 0.05. A minimum frequency of 0.9 was used to define homozygous variants. Variant quality was assessed by examining subsets of variant sequences with Sanger sequencing and by using simulated alignments. Primers for Sanger sequencing experiments are shown in Additional file 15. Sanger sequencing was performed on PCR products at the Australian Genome Research Facility. For simulated alignments, the T. orientalis Shintoku sequence was modified by the msbar program of EMBOSS [81] to contain approximately 90,000 point, codon and block insertion/deletion events and 900,000 substitution events. Simulated reads were generated from simulated genomes using ART vMountRainier 2016–06-05 [82] and mixed into one fastq file. False discovery rate was calculated by aligning simulated to experimentally determined sequences and comparing true and detected variants.

Recombination and selection analysis

Recombination analysis was performed on concatenated SNV alignments to allow direct comparison to previous attempts at examining recombination in Theileria spp. [23]. These methods are potentially susceptible to error from highly divergent sequences (< 60% identity) and reduced SNV density information. To limit false positive results, we performed recombination analysis using six recombination tests, namely Geneconv, MaxChi, RDP, BootScan, 3Seq and SiScan as previously described with the exception that, due to higher SNV density, SNVs were not discounted if they were within 100 bp of another SNV [23]. For dN/dS analysis, SNV-containing genomes were constructed using homogeneous SNVs from Fish Creek and Goon Nure strain variant analysis with the FastaAlternateReferenceMaker tool from the Genome Analysis Toolkit v3.2.2 [83]. Coding sequence alignments of Reference and SNV-containing genomes were generated for gene regions of 14 × or greater sequencing coverage using customised python scripts and biopython [84]. Coding DNA sequences (CDS) were excluded where sequencing coverage at > 14 × made up less than 50% of the CDS. dN/dS ratios and synonymous/non-synonymous mutations were calculated for coding sequences using KaKs Calculator v2.0 [85]. Predicted surface proteins were identified using SignalP 4.0 [86] and TMHMM [87].

Piroplasmida phylogenomic analysis

Piroplasmida phylogeny was examined using single copy orthogroups identified during ortholog clustering (outlined above). A total of 654 orthologous groups with single copy genes found in all 11 genomes were identified using Orthofinder v2.1.2 [21], with initial search results filtered to retain only groups with an e-value <1e-30. Sequences from each of the 654 orthologous groups were aligned and trimmed using MAFFT v7.310 and trimAl v1.3 [88, 89] as described previously [27] with the following alterations. Sequence alignments were trimmed using the nogaps automated option and two orthologous groups were removed from the final analysis after trimming due to poor alignment and high trimming. A supermatrix alignment (261,036 residues) was generated by concatenating individual gene alignments using a customised python script. Protein evolution model selection was performed for each gene of the supermatrix alignment using Prottest v3.4 [90]. The supermatrix tree was inferred with RAxML v8.2.4 as previously described [27, 91]. Average nucleotide identity comparisons were calculated using pyani v0.2.3 (https://github.com/widdowquinn/pyani) using the ANIb method described in [92].

Conclusion

The draft genomes generated in this study from three genotypes of T. orientalis allowed us to provide the first phylogenomic evidence for species-level differences between the pathogenic Ikeda and apathogenic Chitose and Buffeli genotypes. Additionally, significant differences between the Chitose and Buffeli genotypes were equivalent to those observed between murine Plasmodium spp. indicating that a subspecies classification may be appropriate for those genotypes. Very high average nucleotide identity between an Australian (Robertson) and a Japanese (Shintoku) Ikeda isolate was also observed. Genomewide analysis of variation used in this study should be expanded to include additional strains to elucidate the origin of T. orientalis Ikeda infection in Australia and support future vaccine development.

Abbreviations

- ANI:

-

Average nucelotide identity

- CDS:

-

Coding DNA sequence

- dN/dS:

-

Ratio of non-synonymous/Synonymous mutations per site

- D-PBS:

-

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline

- EST:

-

Expressed sequence tag

- FAINT:

-

Frequently associated IN Theileria

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- LC-MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography - tandem mass spectrometry

- MPSP:

-

Major piroplasm surface protein

- PCV:

-

Packed cell volume

- RDP:

-

Recombination detection program

- SDS-PAGE:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate - polyAcrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

References

Sivakumar T, Hayashida K, Sugimoto C, Yokoyama N. Evolution and genetic diversity of Theileria. Infect, Genet Evol. 2014;27:250–63.

Watts JG, Playford MC, Hickey KL. Theileria orientalis: a review. N Z Vet J. 2016;64(1):3–9.

Chae JS, Allsopp BA, Waghela SD, Park JH, Kakuda T, Sugimoto C, Allsopp MT, Wagner GG, Holman PJ. A study of the systematics of Theileria spp. based upon small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Parasitol Res. 1999;85(11):877–83.

Fujisaki K, Kawazu S, Kamio T. The taxonomy of the bovine Theileria spp. Parasitol Today. 1994;10(1):31–3.

Uilenberg G, Perie NM, Spanjer AA, Franssen FF. Theileria orientalis, a cosmopolitan blood parasite of cattle: demonstration of the schizont stage. Res Vet Sci. 1985;38(3):352–60.

Stewart NP, de Vos AJ, Shiels IA, Jorgensen WK. Transmission of Theileria buffeli to cattle by Haemaphysalis bancrofti fed on artificially infected mice. Vet Parasitol. 1989;34(1–2):123–7.

Jeong W, Yoon SH, An DJ, Cho SH, Lee KK, Kim JY. A molecular phylogeny of the benign Theileria parasites based on major piroplasm surface protein (MPSP) gene sequences. Parasitology. 2010;137(2):241–9.

Khukhuu A, Lan DT, Long PT, Ueno A, Li Y, Luo Y, Macedo AC, Matsumoto K, Inokuma H, Kawazu S, et al. Molecular epidemiological survey of Theileria orientalis in Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. J Vet Med Sci. 2011;73(5):701–5.

Eamens GJ, Bailey G, Jenkins C, Gonsalves JR. Significance of Theileria orientalis types in individual affected beef herds in new South Wales based on clinical, smear and PCR findings. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196(1–2):96–105.

Bogema DR, Deutscher AT, Fell S, Collins D, Eamens GJ, Jenkins C. Development and validation of a quantitative PCR assay using multiplexed hydrolysis probes for detection and quantification of Theileria orientalis isolates and differentiation of clinically relevant subtypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(3):941–50.

Ota N, Mizuno D, Kuboki N, Igarashi I, Nakamura Y, Yamashina H, Hanzaike T, Fujii K, Onoe S, Hata H, et al. Epidemiological survey of Theileria orientalis infection in grazing cattle in the eastern part of Hokkaido, Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2009;71(7):937–44.

Beck HP, Blake D, Darde ML, Felger I, Pedraza-Diaz S, Regidor-Cerrillo J, Gomez-Bautista M, Ortega-Mora LM, Putignani L, Shiels B, et al. Molecular approaches to diversity of populations of apicomplexan parasites. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39(2):175–89.

Miotto O, Almagro-Garcia J, Manske M, MacInnis B, Campino S, Rockett KA, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, et al. Multiple populations of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Cambodia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(6):648. +

Vaughan AM, Kappe SHI. Malaria vaccine development: persistent challenges. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(3):324–31.

Hayashida K, Hara Y, Abe T, Yamasaki C, Toyoda A, Kosuge T, Suzuki Y, Sato Y, Kawashima S, Katayama T, et al. Comparative genome analysis of three eukaryotic parasites with differing abilities to transform leukocytes reveals key mediators of Theileria-induced leukocyte transformation. MBio. 2012;3(5):e00204–12.

Gardner MJ, Bishop R, Shah T, de Villiers EP, Carlton JM, Hall N, Ren Q, Paulsen IT, Pain A, Berriman M, et al. Genome sequence of Theileria parva, a bovine pathogen that transforms lymphocytes. Science. 2005;309(5731):134–7.

Kappmeyer LS, Thiagarajan M, Herndon DR, Ramsay JD, Caler E, Djikeng A, Gillespie JJ, Lau AO, Roalson EH, Silva JC, et al. Comparative genomic analysis and phylogenetic position of Theileria equi. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:603.

Pain A, Renauld H, Berriman M, Murphy L, Yeats CA, Weir W, Kerhornou A, Aslett M, Bishop R, Bouchier C, et al. Genome of the host-cell transforming parasite Theileria annulata compared with T. parva. Science. 2005;309(5731):131–3.

Jenkins C, Micallef M, Alex SM, Collins D, Djordjevicb SP, Bogema DR. Temporal dynamics and subpopulation analysis of Theileria orientalis genotypes in cattle. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;32:199–207.

Koboldt DC, Zhang QY, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22(3):568–76.

Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:157.

Kamau J, de Vos AJ, Playford M, Salim B, Kinyanjui P, Sugimoto C. Emergence of new types of Theileria orientalis in Australian cattle and possible cause of theileriosis outbreaks. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:22.

Hayashida K, Abe T, Weir W, Nakao R, Ito K, Kajino K, Suzuki Y, Jongejan F, Geysen D, Sugimoto C. Whole-genome sequencing of Theileria parva strains provides insight into parasite migration and diversification in the African continent. DNA Res. 2013;20(3):209–20.

Hikosaka K, Watanabe Y, Tsuji N, Kita K, Kishine H, Arisue N, Palacpac NMQ, Kawazu S, Sawai H, Horii T, et al. Divergence of the mitochondrial genome structure in the apicomplexan parasites, Babesia and Theileria. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(5):1107–16.

Hikosaka K, Tsuji N, Watanabe Y, Kishine H, Horii T, Igarashi I, Kita K, Tanabe K. Novel type of linear mitochondrial genomes with dual flip-flop inversion system in apicomplexan parasites, Babesia microti and Babesia rodhaini. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:622.

Endo T, Ikeo K, Gojobori T. Large-scale search for genes on which positive selection may operate. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13(5):685–90.

Cornillot E, Hadj-Kaddour K, Dassouli A, Noel B, Ranwez V, Vacherie B, Augagneur Y, Bres V, Duclos A, Randazzo S, et al. Sequencing of the smallest apicomplexan genome from the human pathogen Babesia microti. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(18):9102–14.

Uilenberg G. Theileria sergenti. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175(3–4):386.

Kim SJ, Tsuji M, Kubota S, Wei Q, Lee JM, Ishihara C, Onuma M. Sequence analysis of the major piroplasm surface protein gene of benign bovine Theileria parasites in East Asia. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28(8):1219–27.

Onuma M, Kakuda T, Sugimoto C. Theileria parasite infection in East Asia and control of the disease. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;21(3):165–77.

Kawazu SI, Kamio T, Sekizaki T, Fujisaki K. Theileria sergenti and T. buffeli: polymerase chain reaction-based marker system for differentiating the parasite species from infected cattle blood and infected tick salivary gland. Exp Parasitol. 1995;81(4):430–5.

Ziam H, Kelanamer R, Aissi M, Ababou A, Berkvens D, Geysen D. Prevalence of bovine theileriosis in north central region of Algeria by real-time polymerase chain reaction with a note on its distribution. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2015;47(5):787–96.

Omar Abdallah M, Niu Q, Yu P, Guan G, Yang J, Chen Z, Liu G, Wei Y, Luo J, Yin H. Identification of piroplasm infection in questing ticks by RLB: a broad range extension of tick-borne piroplasm in China? Parasitol Res. 2016;115(5):2035–44.

OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health). Theileriosis. In: Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals. Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health. p. 2015.

Aparna M, Vimalkumar MB, Varghese S, Senthilvel K, Ajithkumar KG, Raji K, Syamala K, Priya MN, Deepa CK, Jyothimol G, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of bovine Theileria spp. isolated in South India. Trop Biomed. 2013;30(2):281–90.

Gebrekidan H, Gasser RB, Baneth G, Yasur-Landau D, Nachum-Biala Y, Hailu A, Jabbar A. Molecular characterization of Theileria orientalis from cattle in Ethiopia. Ticks and tick-borne diseases. 2016;7(5):742–7.

Boenigk J, Ereshefsky M, Hoef-Emden K, Mallet J, Bass D. Concepts in protistology: species definitions and boundaries. Eur J Protistol. 2012;48(2):96–102.

Stentiford GD, Feist SW, Stone DM, Peeler EJ, Bass D. Policy, phylogeny, and the parasite. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(6):274–81.

Kakuda T, Kubota S, Sugimoto C, Baek BK, Yin H, Onuma M. Analysis of immunodominant piroplasm surface protein genes of benign Theileria parasites distributed in China and Korea by allele-specific polymerase chain reaction. J Vet Med Sci. 1998;60(2):237–9.

Zakimi S, Kim JY, Oshiro M, Hayashida K, Fujisaki K, Sugimoto C. Genetic diversity of benign Theileria parasites of cattle in the Okinawa prefecture. J Vet Med Sci. 2006;68(12):1335–8.

Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G, Ciulla D, Tabbaa D, Highlander SK, Sodergren E, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21(3):494–504.

Hammer JF, Emery D, Bogema DR, Jenkins C. Detection of Theileria orientalis genotypes in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks from southern Australia. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:229.

Wagyu in Australia http://www.wagyu.org.au/wagyu-in-australia/. Accessed 24 Apr 2018.

Choi CY, Kang CW, Kim EM, Lee S, Moon KH, Oh MR, Yamauchi T, Yun YM. Ticks collected from migratory birds, including a new record of Haemaphysalis formosensis, on Jeju Island, Korea. Exp Appl Acarol. 2014;62(4):557–66.

Hasle G. Transport of ixodid ticks and tick-borne pathogens by migratory birds. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:48.

Stewart NP, Uilenberg G, deVos AJ. Review of Australian species of the Theileria, with special reference to Theileria buffeli of cattle. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1996;28(1):81–90.

Graham SP, Pelle R, Honda Y, Mwangi DM, Tonukari NJ, Yamage M, Glew EJ, de Villiers EP, Shah T, Bishop R, et al. Theileria parva candidate vaccine antigens recognized by immune bovine cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(9):3286–91.

Akhouri RR, Bhattacharyya A, Pattnaik P, Malhotra P, Sharma A. Structural and functional dissection of the adhesive domains of Plasmodium falciparum thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP). Biochem J. 2004;379:815–22.

Muller HM, Reckmann I, Hollingdale MR, Bujard H, Robson KJH, Crisanti A. Thrombospondin related anonymous protein (TRAP) of Plasmodium falciparum binds specifically to sulfated glycoconjugates and to HepG2 hepatoma-cells suggesting a role for this molecule in sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes. EMBO J. 1993;12(7):2881–9.

Zhou JL, Fukumoto S, Jia HL, Yokoyama N, Zhang GH, Fujisaki K, Lin JJ, Xuan XN. Characterization of the Babesia gibsoni P18 as a homologue of thrombospondin related adhesive protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;148(2):190–8.

Gaffar FR, Yatsuda AP, Franssen FFJ, de Vries E. A Babesia bovis merozoite protein with a domain architecture highly similar to the thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP) present in Plasmodium sporozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;136(1):25–34.

Rogers WO, Rogers MD, Hedstrom RC, Hoffman SL. Characterization of the gene encoding sporozoite surface protein-2, a protective Plasmodium yoelii sporozoite antigen. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;53(1–2):45–51.

Takemae H, Sugi T, Kobayashi K, Murakoshi F, Recuenco FC, Ishiwa A, Inomata A, Horimoto T, Yokoyama N, Kato K. Interaction between Theileria orientalis 23-kDa piroplasm membrane protein and heparin. Jap J Vet Res. 2014;62(1–2):17–24.

Takemae H, Sugi T, Kobayashi K, Murakoshi F, Recuenco FC, Ishiwa A, Inomata A, Horimoto T, Yokoyama N, Kato K. Analyses of the binding between Theileria orientalis major piroplasm surface proteins and bovine red blood cells. Vet Rec. 2014;175(6):149.

Shimizu S, Suzuki K, Nakamura K, Kadota K, Fujisaki K, Ito S, Minami T. Isolation of Theileria sergenti piroplasms from infected erythrocytes and development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent-assay for serodiagnosis of Theileria sergenti infections. Res Vet Sci. 1988;45(2):206–12.

Tacchi JL, Raymond BB, Haynes PA, Berry IJ, Widjaja M, Bogema DR, Woolley LK, Jenkins C, Minion FC, Padula MP, et al. Post-translational processing targets functionally diverse proteins in mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Open Biol. 2016;6(2):150210.

Coil D, Jospin G, Darling AE. A5-miseq: an updated pipeline to assemble microbial genomes from Illumina MiSeq data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2015;31(4):587–9.

Chu J, Sadeghi S, Raymond A, Jackman SD, Nip KM, Mar R, Mohamadi H, Butterfield YS, Robertson AG, Birol I. BioBloom tools: fast, accurate and memory-efficient host species sequence screening using bloom filters. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(23):3402–4.

Zimin AV, Delcher AL, Florea L, Kelley DR, Schatz MC, Puiu D, Hanrahan F, Pertea G, Van Tassell CP, Sonstegard TS, et al. A whole-genome assembly of the domestic cow, Bos taurus. Genome Biol. 2009;10(4):R42.

Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, Salzberg SL. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5(2):R12.

Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11147.

Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SMC, Parra G, Ross E, Moore B, Holt C, Sánchez Alvarado A, Yandell M. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18(1):188–96.

Stanke M, Steinkamp R, Waack S, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server):W309–12.

Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O'Donnell CJ, de Bakker PIW. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(24):2938–9.

Lomsadze A, Burns PD, Borodovsky M. Integration of mapped RNA-Seq reads into automatic training of eukaryotic gene finding algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(15):e119.

Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, Orvis J, White O, Buell CR, Wortman JR. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9(1):R7.

Slater GS, Birney E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:31.

Otto TD, Dillon GP, Degrave WS, Berriman M. RATT: rapid annotation transfer tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(9):e57.

Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–6.

Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2014;30(9):1236–40.

Myhre S, Tveit H, Mollestad T, Laegreid A. Additional gene ontology structure for improved biological reasoning. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2006;22(16):2020–7.

Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S, et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419(6906):498–511.

Brayton KA, Lau AOT, Herndon DR, Hannick L, Kappmeyer LS, Berens SJ, Bidwell SL, Brown WC, Crabtree J, Fadrosh D, et al. Genome sequence of Babesia bovis and comparative analysis of apicomplexan hemoprotozoa. PLoS Path. 2007;3(10):1401–13.

Jackson AP, Otto TD, Darby A, Ramaprasad A, Xia D, Echaide IE, Farber M, Gahlot S, Gamble J, Gupta D, et al. The evolutionary dynamics of variant antigen genes in Babesia reveal a history of genomic innovation underlying host-parasite interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(11):7113–31.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20.

Breese MR, Liu YL. NGSUtils: a software suite for analyzing and manipulating next-generation sequencing datasets. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(4):494–6.

Sedlazeck FJ, Rescheneder P, von Haeseler A. NextGenMap: fast and accurate read mapping in highly polymorphic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(21):2790–1.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Proc GPD. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9.

Manary MJ, Singhakul SS, Flannery EL, Bopp SER, Corey VC, Bright AT, McNamara CW, Walker JR, Winzeler EA. Identification of pathogen genomic variants through an integrated pipeline. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:63.

Warden CD, Adamson A, Neuhausen SL, Wu XW: Detailed comparison of two popular variant calling packages for exome and targeted exon studies. Peerj. 2014; 2.

Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16(6):276–7.

Huang WC, Li LP, Myers JR, Marth GT. ART: a next-generation sequencing read simulator. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(4):593–4.

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–303.

Cock PJA, Antao T, Chang JT, Chapman BA, Cox CJ, Dalke A, Friedberg I, Hamelryck T, Kauff F, Wilczynski B, et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1422–3.

Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2010;8(1):77–80.

Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8(10):785–6.

Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305(3):567–80.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7.

Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1972–3.

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(8):1164–5.

Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(21):2688–90.

Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA, Coenye T, Vandamme P, Tiedje JM. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57(Pt 1):81–91.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. Phillip Carter and Susan Robinson of the Tick Fever Centre (Wacol, Queensland) for assistance with cattle inoculations, Neil Charman of the Gippsland Research Station (Fish Creek, Victoria) for assistance in collecting the Fish Creek strain, and Sherin Alex (UTS) and Shayne Fell (NSW DPI) for their generous assistance purifying T. orientalis piroplasms from cattle blood.

Funding

This work was funded by a Meat and Livestock Australia (Project B.AHE.0213) grant to CJ. Meat and Livestock Australia had no role in the design of this study or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Availability of data and materials

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accessions MACL00000000 (Robertson), MACJ00000000 (Fish Creek) and MACK00000000 (Goon Nure), versions MACL01000000, MACJ01000000 and MACK01000000 are described in this paper. Sequencing yielded 3461802, 2938990 and 2940960 paired reads, corresponding to 622, 735 and 735 Mbp data for Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure samples, respectively. Sequence read data has been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive, under accessions SRP076317 (Robertson), SRP076318 (Fish Creek) and SRP076319 (Goon Nure).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CJ conceived of this study while DRB, AED and SPD contributed to the study design. DRB, MLM, ML, MPP and CJ carried out the experimental work associated with this study. DRB conducted the in silico analyses and drafted the manuscript. CJ, AED and SPD edited the manuscript and all authors reviewed and approved the final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was carried out in accordance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes at the Tick Fever Centre, Wacol, Queensland and was approved by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Animal Ethics Committee (Approval SA 2013/09/443).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Mauve alignments with reference genome. Reference alignments between T. orientalis Shintoku whole genome sequence and Robertson (top), Fish Creek (middle) and Goon Nure (bottom) strain sequences. Alignments were generated by Mauve. Coloured blocks represent locally collinear blocks (LCBs) which are conserved segments determined to be internally free from genome rearrangements. Lines connecting top sequence to bottom demonstrate aligned LCBs. All alignments are shown with Shintoku as the upper sequence and Australian isolate as the lower. Alignment width is determined by the longest sequence, white sections represent sequence which does not align to Shintoku with Mauve, but may also represent duplicated sequence. (TIF 2219 kb)

Additional file 2:

Dot plots of nucmer alignments. Dot plots of Robertson, Fish Creek and Goon Nure sequences against the Shintoku reference sequence (A) and self alignment (B). Alignments were generated using nucmer. Reference alignments represent longest mutually consistent set (delta-filter -g), self alignments include all additional matches > 50 bp in length and 75% identify (delta-filter -i 75 -l 50). Purple lines represent primary or highest scoring matches, blue lines represent additional matches. (TIF 9120 kb)

Additional file 3:

Validation of SNV variant calling pipeline. Validation statistics of SNV calling pipeline generated by comparison to short sections of Sanger sequencing. (DOC 32 kb)

Additional file 4:

SNV density vs genomic loci histograms. SNV density vs genomic loci histograms of the Robertson (top), Fish Creek (middle) and Goon Nure bottom) strains. Y-axis represents number of SNV per 10 kb axis represents whole genome position, chromosomes are represented by colour. (TIF 846 kb)

Additional file 5:

SNVs per open reading frame. Number of SNVs found in each gene of the Robertson isolate when mapped to the reference Shintoku genome. (PDF 203 kb)

Additional file 6:

Orthologous genes vs orthologous groups. Number of orthologous genes against orthologous groups containing x number of genes per isolate. (TIF 1293 kb)

Additional file 7:

Coding sequence average depth of coverage. Average coverage depth of coding sequences for orthogroups grouped by genes per isolate (Gene numbers containing > 4 orthogroups not shown). (DOC 29 kb)

Additional file 8:

Proteins with no blastp matches compared to reference genome. Examination of proteins that produced no blastp match to the Shintoku predicted proteome, by blastp searches of the nr database. (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 9:

Predicted recombination events. Details of predicted recombination events shown in Fig. 2. (PDF 30 kb)

Additional file 10:

dN/dS ratios. Calculated dN/dS (a.k.a. KaKs) ratios for the predicted Shintoku proteome by comparison to mapped Fish Creek (Chitose) and Goon Nure (Buffeli) isolate sequences. (PDF 913 kb)

Additional file 11:

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) for members of the Plasmodium genus. Pairwise ANI values for species of the Plasmodium genus with publically-available genome sequences. (XLSX 11 kb)

Additional file 12:

Fish Creek maker parameters. Parameters used for the annotation of the Fish Creek genome sequence using the maker pipeline. (GZ 3 kb)

Additional file 13:

Goon Nure maker parameters. Parameters used for the annotation of the Goon Nure genome sequence using the maker pipeline. (GZ 3 kb)

Additional file 14:

Robertson maker parameters. Parameters used for the annotation of the Robertson genome sequence using the maker pipeline. (GZ 3 kb)

Additional file 15:

Primers used in this study. Primers used for Sanger sequencing validation of the SNV calling pipeline. (DOC 44 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bogema, D.R., Micallef, M.L., Liu, M. et al. Analysis of Theileria orientalis draft genome sequences reveals potential species-level divergence of the Ikeda, Chitose and Buffeli genotypes. BMC Genomics 19, 298 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4701-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4701-2