Abstract

Background

Organisms typically face infection by diverse pathogens, and hosts are thought to have developed specific responses to each type of pathogen they encounter. The advent of transcriptomics now makes it possible to test this hypothesis and compare host gene expression responses to multiple pathogens at a genome-wide scale. Here, we performed a meta-analysis of multiple published and new transcriptomes using a newly developed bioinformatics approach that filters genes based on their expression profile across datasets. Thereby, we identified common and unique molecular responses of a model host species, the honey bee (Apis mellifera), to its major pathogens and parasites: the Microsporidia Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae, RNA viruses, and the ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor, which transmits viruses.

Results

We identified a common suite of genes and conserved molecular pathways that respond to all investigated pathogens, a result that suggests a commonality in response mechanisms to diverse pathogens. We found that genes differentially expressed after infection exhibit a higher evolutionary rate than non-differentially expressed genes. Using our new bioinformatics approach, we unveiled additional pathogen-specific responses of honey bees; we found that apoptosis appeared to be an important response following microsporidian infection, while genes from the immune signalling pathways, Toll and Imd, were differentially expressed after Varroa/virus infection. Finally, we applied our bioinformatics approach and generated a gene co-expression network to identify highly connected (hub) genes that may represent important mediators and regulators of anti-pathogen responses.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis generated a comprehensive overview of the host metabolic and other biological processes that mediate interactions between insects and their pathogens. We identified key host genes and pathways that respond to phylogenetically diverse pathogens, representing an important source for future functional studies as well as offering new routes to identify or generate pathogen resilient honey bee stocks. The statistical and bioinformatics approaches that were developed for this study are broadly applicable to synthesize information across transcriptomic datasets. These approaches will likely have utility in addressing a variety of biological questions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eukaryotes are natural hosts of multiple pathogens. Consequently, host immune systems have evolved efficient responses to threats of a different nature, such as viruses, bacteria or eukaryotic parasites. In vertebrates, adaptive immune mechanisms and antibody-mediated defences confer pathogen-specific responses [1]. Conversely, invertebrates lack these adaptive immune defences and rely primarily on innate immunity; they therefore have long been considered rather non-specific in their immune response. However, as insect immunological research has progressed, the specificity of insect antimicrobial action has become well established [2], with evidence of immune memory [3, 4] and pathogen-genotype to host-genotype interactions demonstrated in insect models [5].

Eusocial insects, including honey bees (Apis mellifera), establish large colonies comprised of thousands of related individuals, living at high density, sharing food in extended interactions and very high nest homeostasis; this lifestyle provides advantages in terms of social immunity [6] but also facilitates microbe transmission within the colony and promotes multiple infections [7]. Additionally, comparative genomics has revealed a loss of canonical immune genes in bees of social and solitary lifestyle compared to other insects such as flies, Nasonia vitripennis and Tribolium castaneum, that questioned the ability of bees’ immune system to respond specifically and efficiently to diverse, emerging pathogens [8]. Indeed, parasites and pathogens are considered one of the major factors driving global losses of honey bee colonies [9–11], which in turn threaten plant pollination, which is an important ecosystem service carried out by both managed and wild bees [12]. Key eukaryotic honey bee pathogens include two microsporidian gut parasites: Nosema apis, which primarily infects the Western honey bee A. mellifera, and Nosema ceranae, which was first described as a pathogen of the Eastern honey bee Apis cerana and more recently has become the predominant microsporidial pathogen infecting A. mellifera [13]. Single-stranded RNA viruses represent another key group of honey bee pathogens [14]. Several of these viruses are transmitted by Varroa destructor, an invasive ectoparasitic mite that switched host from A. cerana to A. mellifera in the past half century [15]. The ensuing shift of viruses from oral to vectored transmission by Varroa has modified the epidemiology and potentially increased the virulence of viral diseases such as deformed wing virus, thereby producing a significant threat to honey bee populations [16–18]. Importantly, multiple pathogens and parasites may interact while co-infecting honey bees to modify the dynamic of their infection [19, 20], and potentially increasing host mortality [17, 21].

Understanding the molecular interactions between the honey bee and its pathogens is crucial in revealing their role in host health and, ultimately, colony losses [22]. Recent advances in genome sequencing technologies and improvements in genome annotation of the honey bee have facilitated fine scale mapping of bee immune responses against multiple pathogens and parasites at the genomic level [23]. Several studies examining the transcriptional response of honey bees to their primary pathogens, namely Nosema, Varroa and viruses, have already provided considerable insight into the molecular mechanisms mediating host-parasite interactions [24–29], yet these studies have also revealed idiosyncrasies across datasets.

Analysis of multiple transcriptome datasets provides not only the opportunity to detect subtle changes in gene expression, but also to highlight commonalities in host responses. Recent studies in mosquitoes and humans have demonstrated the power of meta-analyses to reveal key host responses to multiple pathogen infections [30–32]. To comprehensively characterize the interactions between honey bees and their major pathogens and pests, we performed a meta-analysis of the transcriptional responses to Nosema, Varroa and viruses. We collected the gene expression profiles of 7,077 genes across 19 published and new transcriptome datasets of experimentally infected or parasitized honey bees, and utilized statistical and bioinformatics analyses that we newly developed (a ‘directed rank product analysis’) to perform a synthesis of gene expression patterns from multiple studies and platforms. This resulted in a robust analysis that, (i) identified common genes and pathways regulated in response to different pathogens, (ii) identified genes and pathways uniquely regulated in response to one pathogen in a particular body part or tissue, and (iii) enabled building a gene co-expression network to identify regulatory genes and new gene interactions within the honey bee transcriptome. Our analysis provides new insights into the molecular and physiological mechanisms that underpin the interactions between honey bees and their major pathogens.

Results

Multivariate analysis

We performed a multidimensional scaling analysis to visualize the spread of the 19 transcriptome datasets. This showed that gene expression levels vary less within a study than between studies and suggests that gene expression profiles are markedly influenced by experimental design (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Thus, comparisons across studies to find commonly and consistently regulated gene expression patterns are undoubtedly hindered by this large amount of variation, highlighting the importance of performing a meta-analysis with appropriate bioinformatics approaches to obtain robust and reproducible results.

Rank product analysis

Previous comparative analyses of honey bee immune responses across transcriptome datasets simply involved determining if there was a significant overlap in the differentially expressed gene lists from different studies [24, 25, 27, 28]. However, the significant variation in expression levels between studies (Additional file 1: Figure S1) undoubtedly reduces the power of such comparisons. Thus, we employed a rank product analysis to identify sets of genes that are significantly differentially expressed across the 19 transcriptomes datasets we collected. The rank product analysis is a non-parametric statistic that identifies genes that are consistently highly ranked in a number of datasets, based on the gene expression fold changes.

In total, we found 344 genes with significant differential expression across datasets, categorized by (i) 56 genes with significant increased expression (i.e. up-regulated) across datasets, (ii) 109 with significant decreased expression (i.e. down-regulated) across datasets and (iii) 179 genes with significant differential expression (i.e. differentially-regulated), up-regulated in some studies, down in others (Fig. 1; Additional file 1: Figures S2 and S3; Additional file 2: Tables ST1-ST3). Note that using this rank product analysis, a gene may be statistically significantly up-regulated across all 19 datasets but still be down-regulated in one or more datasets (and vice-versa for significantly down-regulated genes). In fact, subsets of up-regulated genes (45 of 56 genes) and down-regulated genes (83 of 109 genes) were also categorized as differentially-regulated (up- and down-regulated across datasets; see Additional file 1: Figure S3). Notably, one gene, encoding the antimicrobial peptide (AMP) hymenoptaecin, was present in all three categories due to its extreme differential expression (high and low) across all datasets (Additional file 1: Figure S4).

Heat maps illustrating the expression levels (relative ranks) of the 344 significantly regulated genes across the 19 transcriptome datasets. Genes are categorized as 56 up-regulated genes (top left), 109 down-regulated genes (bottom left), and 179 differentially regulated (up and down) genes (right). Orange shows increased expression and blue decreased expression after pathogen infection. Top classification is N for Nosema infection, N/V for Nosema and RNA virus co-infection, V for virus, and M for Varroa mite (‘Varroa plus virus’). Numbers at the bottom correspond to dataset numbers in Table 2. Each row represents the differential expression of the same gene across all 19 datasets. In each category, genes are ordered following the arithmetic means of their ranks displayed in the right column of the heat map. Note the presence of genes showing decreased expression in some datasets although found as statistically up-regulated across datasets, and vice-versa

Gene evolutionary rate

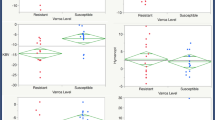

We compared the evolutionary rate, obtained from the database OrthoDB and measured as the average of protein sequence identities from pairwise alignments across 12 bee genomes [33], of genes that were significantly differentially expressed across the transcriptome datasets and genes that were not differentially expressed. Genes showing significant differential expression across the transcriptome datasets exhibited a higher evolutionary rate than non-differentially expressed genes (Kruskal-Wallis χ 2 = 103.1476; df = 3; p < 0.001; Fig. 2), suggesting rapid evolution of genes responding to pathogen infection. All three categories of differentially expressed genes showed significantly higher evolutionary rates than non-differentially expressed genes (Dunn’s test with Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-values: differentially-regulated vs. non-differentially expressed Z = −6.536, p < 0.001; up-regulated vs. non-differentially expressed Z = −4.183, p < 0.001; down-regulated vs. non-differentially expressed Z = −6.781, p < 0.001), while no difference was observed between the different categories of regulated genes. Note that an analysis of the dN/dS ratios may have provided more insights into the type of selection (e.g. positive, relaxed) but this was beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Comparison of the evolutionary rate between genes showing significant differential expression and genes without significant differential expression across the 19 datasets. Relative evolutionary rates on the Y-axis are quantified from pairwise alignments of the protein sequences, and represent the average of inter-species protein sequence identities normalized to the average identity of all inter-species orthologs from OrthoDB [33]. The vertical black lines along the median and mean values of each category represent the standard deviation (thick lines) and the 95% confidence intervals (thin lines). Horizontally, the width of each violin box represents the density of the data values, i.e. the distribution of the data along the y axes, for each category

Specific host responses

We explored the specific response of honey bees to pathogens using our newly developed directed rank product analysis. By this method, we adjusted the rank product analysis approach to identifying genes whose expression followed a specific pattern. This new method consists in defining a theoretical gene expression profile corresponding to selected parameters (e.g. treatment, development time or tissue-specific responses), and identifies genes exhibiting a similar expression profile. Here, we identified genes differentially expressed in bees infected by one pathogen type but non-differentially expressed in bees infected by other pathogens.

We first identified genes specifically involved in the response to Nosema infection in abdominal tissues: midgut, fat body, or complete abdomen (Additional file 2: Tables ST4 and ST5). The functional analysis of 104 genes with increased expression upon Nosema infection revealed overrepresentation of genes encoding enzymes and proteins involved in metabolic processes, catalytic activities, and transporter activity (Additional file 2: Table ST6), while genes related to cell components were overrepresented among 88 down-regulated genes after Nosema infection (Additional file 2: Table ST7).

To explore the specific response of honey bees to viruses, we examined the transcriptome datasets of honey bees experimentally infected by RNA viruses or parasitized by Varroa mites and, thus, by viruses. We justify merging Varroa and virus datasets with the idea that the impact of Varroa may stem largely from damage to the cuticle during feeding as well as from transmitted viruses, thus suggesting little immediate impact of sole Varroa parasitism on immune gene expression of the host [34]. We identified 167 genes differentially expressed specifically in response to Varroa/virus treatments (88 up-regulated and 79 down-regulated; Additional file 2: Tables ST8 and ST9). The functional analysis of genes regulated after parasitism by Varroa and infection by viruses did not show any significantly overrepresented GO terms for up-regulated genes, but the overrepresentation of nutrient reservoir activity for down-regulated genes (Additional file 2: Tables ST10 and ST11).

Gene co-expression network

Our directed rank product method enabled us to detect genes with similar and opposite expression profiles across the 19 transcriptome datasets and to build a gene co-expression network. We found a total of 16,110 significant inter-gene connections, with nearly half of the 7,077 genes (N = 3,589) interconnected within one major module, while 2,931 genes remained unconnected and 557 genes were placed within small modules of 2 to 11 genes. The majority (98%) of inter-gene connections were observed within the major module, with 12,694 positive (i.e. similar expression profiles) and 3,087 negative (i.e. opposite expression profiles) inter-gene connections (Fig. 3a). Notably, 320 out of the 344 significantly differentially expressed genes from the rank product analysis were identified within the major module, illustrating the tight interconnectivity of the expression regulation of these genes.

Gene co-expression network. a Main module of the gene co-expression network, representing 3,589 interconnected genes. Red nodes show genes significantly regulated across the 19 transcriptome datasets, and black nodes show non-significantly regulated genes. Square nodes show the most connected (hub) genes. Grey edges illustrate positive correlation between two gene expression profiles while blue edges show negative correlations. A file available at https://idata.idiv.de/DDM/Data/ShowData/35 provides the possibility of navigating within the network. b Scatter plot representing the total number of connections (x-axis) over the number of connections to significantly regulated genes across the 19 transcriptome datasets for the most (top 5%, N = 209) connected genes (i.e. hub genes). Red triangles show significantly regulated hub genes, while black dots show non-significantly regulated hub genes. Two hub genes with high connectivity to significantly regulated genes are shown: a kynurenine/alpha-aminoadipate aminotransferase (LOC724239), and a L-lactate dehydrogenase (LOC411188). c Main module from the co-expression network of the immune genes of the honey bee. Coloured nodes represent immune genes from the Toll (purple), JAK/STAT (brown), apoptosis (green), RNAi (blue) and Imd (pink) pathways (see immune genes list in the Additional file 2: Table ST13). Oval nodes show genes with low connectivity, squares show genes with high connectivity (hub genes, with at least 34 connections). Genes significantly regulated across the 19 transcriptome datasets have a red outline. Black edges represent positive co-expression and blue edges are negative co-expression. In insets, the expression profiles across the 19 transcriptome datasets (black lines) of the four immune hub genes (i.e. highly connected immune genes), accompanied by expression profiles of genes with which they are connected. Orange profiles display similar profiles (positive connections, i.e. black lines in the network) and blue reflect opposite profiles (negative connections, i.e. blue lines in the network). The y-axis displays the relative ranks of differential expression level, from up-regulated (value towards 1) to down-regulated (value towards 0)

We identified the top 5% most interconnected genes from all 7,077 genes of this study, which represents 209 hub genes with at least 34 connections to other genes (Additional file 1: Figure S5). Notably, 52 hub genes were significantly differentially expressed across the 19 transcriptome datasets (Fig. 3b; Additional file 2: Table ST12), and differentially expressed genes were significantly more connected than non-differentially expressed genes (Kruskal-Wallis χ 2 = 445.9856, df = 3, p-value < 0.001; Additional file 1: Figure S6).

To identify novel candidate genes involved in immune regulation, we collected all interactions involving canonical immune genes and generated an immune network composed of 26 modules containing at least 2 interconnected genes. The major module of this immune network contained 281 genes, including 25 immune genes from all immune pathways (Fig. 3c; Additional file 2: Table ST13). A total of 92 significantly regulated genes from the rank product analysis were present in this immune network, with only one remaining outside the major module.

Discussion

Similar to other eukaryotes, the honey bee is host to many different types of pathogens and harbours in its genome an immune repertoire to provide a specific immune response to this diversity of pathogens [35]. Our meta-analysis of honey bee transcriptional responses to a diverse set of pathogens identified a core set of genes that is common to honey bee anti-pathogen responses, as well as suites of genes that respond specifically to different pathogens and parasites (Fig. 4).

Diagram of the canonical innate immune response of the honey bee. Gene names in colour-filled boxes show evidence of significant regulation after infection by Nosema (yellow), or infection by RNA viruses and/or infestation by Varroa mites (light blue) or all pathogens (grey). Orange lines surrounding a box show increased expression and blue surrounding lines indicate decreased expression after pathogen infection –mixed orange and blue lines show genes found differentially-regulated, either up- or down-regulated across the datasets. Notably, the AMP defensin-1 exhibited increased expression in most of the datasets, but a decreased expression in the abdominal tissues of honey bees infected by Nosema. Therefore, a mixed background and outline colour are displayed. Green surrounding lines show genes found non-significantly regulated in this analysis. Solid lines with arrows show gene interactions reported in the literature, and dotted arrows indicates new potential interactions inferred from our gene co-expression network analysis

General expression patterns

Multivariate analysis indicated that there was a wide between-study variation, likely due to a combination of factors, including variation in technology, experimental approach (e.g., RNA extraction method, infection dose), tissues examined, method of analysis, and host and pathogen genotypes. These substantial differences may explain the limited overlap observed previously between differentially expressed gene lists from different studies [24, 25, 27, 28]. This underscores the importance of our approach, which aims to provide a general methodological and statistical synthesis of studies in order to reveal commonalities in host response to pathogen invasion. It is also a cautionary note for the interpretation of gene expression patterns from single experimental studies, which may in part be due to the idiosyncrasies of a specific experimental paradigm.

Common host response

The common response to multiple pathogens identified in our meta-analysis is characterized by the increased expression of several immune genes, including all canonical AMPs, genes encoding cuticular proteins (LOC552685, CPR14 and LOC100577229), which likely respond to tissue damage by pathogens, and heat-shock related proteins (LOC410087, LOC724367), which may serve as markers of stress during infection response [36]. However, substantially more genes showed decreased expression across transcriptome datasets in response to pathogen infections. Among them we found genes encoding enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, four cytochrome oxidase P450s, the egg yolk protein precursor vitellogenin (Vg), the major royal jelly proteins Mrjp1 and Mrjp9 and two transcriptional repressors hairy and knirps. This reduced expression of genes involved in catalytic and metabolic activities may illustrate the cost of the infection, i.e. a dysregulation as a consequence of pathogen insult as opposed to host adaptive response, or a manipulative response of the host by the pathogen to enhance its own replication. However, several genes regularly reported as responding to pathogen assault were also down-regulated; these genes encode serine proteases, GMC oxidoreductases, Toll-like receptor 13, the putative antimicrobial peptide IRP30, and glucose oxidase, an enzyme involved in colony food sterilisation and a major component of social immunity in honey bees [37]. Down-regulation of immune genes might represent an adaptive manipulation of the host by infecting pathogens, although this remains to be demonstrated.

An additional 179 genes showed significant differential expression but were inconsistently up- and down-regulated across the 19 transcriptome datasets. Among them we found many cytochrome oxidase P450s and immune genes, including the recognition receptors PGRP-S1, PGRP-S2, B-gluc1, SP12 and Serpin-5, and the antimicrobial Lys-2, the gene encoding caspase-like, involved in apoptosis, and ninjurin-1-like, a transmembrane protein induced by the Toll immune pathway and involved in non-apoptotic cell death in Drosophila [38]. Other genes with potential immune activity also showed significantly variable regulation, such as the GMC oxidoreductases 3 and 7, the apidermins Apd-2 and Apd-3 and the hemolymph apolipophorin-III-like protein.

Functional analysis of the 344 significantly regulated genes showed an overrepresentation of genes associated with extracellular regions and response to biotic stimulus (e.g. immune genes involved in response to pathogen invasion), metabolic processes, and nucleotide binding activity (Table 1). Strikingly, breaking down the functional analysis into genes with increased expression and genes with decreased expression, we found no significant GO terms linked to genes with increased expression, while immune, metabolic and regulatory functions were significantly overrepresented in down-regulated genes. Whether this is an adaptive response of the host or a face of immune suppression driven by pathogens is currently not possible to determine.

Interestingly, the common use of immune genes against different types of pathogens may be a consequence of the reduced set of canonical immune genes observed in bees relative to other insect taxa [8], and may reflect a need for a more general rather than specific response against multiple pathogens. However, common host responses have also been described in other models, such as in mosquitoes and humans [30–32]. In humans, this general response to pathogens has been suggested to constitute an ‘alarm signal’, which may be triggered by different cell types, to maximize the detection and the response of infection [31]. The role of the common host response in honey bees remains to be determined.

Genes involved in this common host response (including several immune genes such as hymenoptaecin, def-2, PGRP-S1, B-gluc1) showed higher evolutionary rate among bees than genes which did not show significant expression differences across the transcriptome datasets. Notably, B-gluc1 has recently been shown to be evolving under positive selection in the honey bee [8]. Recent analysis suggested that sociality and the increased pathogen pressure in colonies densely packed with worker bees may be a cause of such rapid evolution in bumble bee immune genes [39]. However, rapid evolution of immune genes may not only arise as a consequence of positive evolution, but also from relaxed selection [40]. Indeed, honey bees do not rely exclusively on canonical immune genes to fight pathogen infections, but can also employ other mechanisms, such as social immunity [6].

Specific response to pathogens

To characterize the specific response of the honey bee to its major pathogens, we identified genes whose expression profile across transcriptome datasets is most similar to a theoretical expression profile, i.e. genes that are up or down-regulated in response to a pathogen type, Microsporidia or Varroa/virus. This method, named here ‘directed rank product analysis’, combines the identification of genes following a specific expression pattern by subtraction of a gene’s differential expression scores (i.e. here, relative ranks), within the statistical framework of the rank product analysis. This method takes advantage of the rank product analysis so that it can detect biologically relevant gene expression changes from heterogeneous datasets obtained from different platforms, microarrays and sequencing [41].

Despite the common gene expression response identified above, we found important differences in the transcription responses of honey bees to Nosema and Varroa/virus infections. The specific response to Nosema includes increased expression of several genes involved in the regulation of cell death by autophagy or apoptosis, such as Atg2, LOC409667, Metap2 and the apoptosis inhibitor dnr1, which confirms the importance of these mechanisms in mediating the interaction between the honey bee and Microsporidia [42, 43]. Other immune genes were up-regulated upon Nosema infection, including: the transcriptional co-factor akirin and lys-3, involved in the Imd pathway, laccase-2, important for melanisation [44] and the venom proteins melittin and secapin, known for their antimicrobial activities [45, 46]. Conversely, the expression of AMP Def-1 and the serine protease SP40 were reduced in Nosema infected honey bees. Two chitin-binding genes showed contrasting response to Nosema infection: while chitinase 5 (Cht5) exhibited increased expression, the cuticular protein chitotriosidase-1 exhibited reduced expression. This may reflect either a direct effect against Nosema or a response to tissue damage induced by the pathogen.

The specific transcriptional-level response against Varroa/virus treatments was characterized by the differential expression of genes from the Imd (iap2 and rel) and Toll pathways (tube and def-2). Although historically described as anti-bacterial and anti-fungal [2], these pathways were recently shown to exhibit differential expression upon viral infection, and potentially playing active roles in the antiviral defence of insects [47], including in honey bees [17, 28, 29, 48, 49]. Particularly, the Toll pathway NF-κB homolog dorsal-1A was shown to be transcriptionally induced in worker honey bees parasitized by Varroa mites, suggesting that dorsal-1A is involved in the control of DWV infections [17]. While activation of the Imd and Toll pathways induces higher expression of AMPs, the antiviral roles of AMPs are not well characterized [47]. Alternatively, these pathways may possibly control the proliferation of haemocytes, which are important for phagocytosis in the insect cellular immune response, and potentially play a role in the antiviral response [50]. Changes in expression levels of AMPs after virus infection may be a consequence of activation of the Toll and Imd pathways, without having a direct functional role against viruses.

Importantly, we did not observe increased expression of genes associated with the RNAi pathway (e.g. Dicer, Ago), though this is an important component of the antiviral response in insects [51, 52] and observed in two studies included in this meta-analysis [24, 28]. The action of the RNAi pathway may be transient, and thus not always captured by transcriptome analysis. Up-regulation of these genes may be detectable only during the early stages of viral infection, which would explain an inconsistent effect in our dataset, since host transcriptomes were measured at different times post-infection. We also found the increased expression of genes encoding a transcription factor (LOC727085), translation factors (EF1-alpha, LOC726500) and post-transcriptional modification proteins (LOC412975, LOC724690), which may illustrate a general transcriptome dysregulation following infection by viruses [53]. Finally, we found the gene encoding Vg to be down-regulated following viral infection, which may reflect a lack of regulation of nutrients and/or an impaired physiology of the host [54]. Vg is also known to mediate the immune response in honey bees [55]. Importantly, lower expression of Vg and increased expression of malvolio (Mvl) –also observed in response to Varroa/virus– are associated with accelerated behavioural maturation and foraging activity in worker honey bees [56, 57]. The altered expression levels of these regulators in infected individuals, and subsequent induction of precocious foraging, is likely an adaptive response against pathogen transmission within the colony [58], one of many potentially adaptive behavioural responses against pathogens [6].

Gene co-expression network

In addition to identifying shared and unique responses to pathogens, our large dataset enabled the exploration of gene co-expression and the identification of new regulatory genes. Among the most interconnected (hub) genes, we found several genes encoding ribosomal proteins and NADH dehydrogenase enzymes. But most importantly, we identified two genes with many inter-gene connections with other differentially expressed genes: a kynurenine/alpha-aminoadipate aminotransferase gene (LOC724239) and an L-lactate dehydrogenase gene (LOC411188), exhibiting 97 and 76 connections, respectively. The expression of both genes were significantly increased in most transcriptome datasets, and connected to a large proportion of genes that exhibited reduced expression (65 and 50% of negative interactions, respectively). We hypothesize that they exert considerable influence on the overall transcriptional response to pathogen infection and thus may be important mediators of the common host response against diverse pathogens. Interestingly, the aminotransferase LOC724239 was recently shown to be involved in trans-generational immune priming in the bumblebee B. terrestris [59], also suggesting a putative immune regulation function in this species.

More specifically, our immune gene co-expression network highlights the interconnection of all immune pathways. We observed the tight co-expression of the genes encoding canonical AMPs, together with other genes with antimicrobial properties (Lys-3, melittin, IRP30), suggesting a concomitant action after pathogen invasion and/or an identical regulatory mechanism. Expression of these AMPs was positively correlated with expression of the genes encoding the recognition protein PGRP-S2 and the serine protease SP14, both of which are involved in signalling within the Toll pathway [35]. Importantly, new immune genes were identified, including the ortholog of the Drosophila gene pirk (LOC100578156), a negative regulator of the immune Imd pathway [60], co-expressed here with PGRP-S2.

Four immune genes are amongst the most connected genes: PGRP-S1, Serpin-5, Socs-5 and Drk. PGRP-S1 and the serine protease inhibitor Serpin-5, involved in the Toll pathway, are known for their immune regulatory activities [35]. In the immune network generated by our meta-analysis, this activity is illustrated by their numerous negative correlations with the expression profiles of other genes. The suppressor of cytokine signalling, Socs-5, is also known to have a negative feedback effect on the JAK/STAT pathway [35]. However any putative immune regulation by Drk, which is important for the activation of MAPK signalling in Drosophila [61], remains unclear. The mechanisms and possible applications behind these large regulatory effects within the honey bee immune system remain to be investigated.

Conclusions

The accumulation of genome-wide studies has provided the opportunity for the analysis of the commonalities and idiosyncrasies in gene expression in host response to pathogen attack. Here, we synthesised 19 transcriptome datasets from experimentally infected honey bees and developed a new bioinformatics method, the directed rank product, to analyse gene expression profiles in order to identify the host specific responses to a diverse set of pathogens, and build a robust co-expression network. Although this method does not account for the amplitude of gene expression changes, using a rank product-based analysis has the advantage of enabling use of data from different platforms (e.g. microarray and RNA sequencing) in a single statistical analysis.

Importantly, our analyses revealed a core set of genes involved in a common host response to phylogenetically distinct pathogens, yet also enabled identification of genes involved in pathogen specific host immune responses. For instance, we showed that conserved pathways are involved in response to multiple pathogens, with the cellular immune response playing a key role in interactions with Nosema in abdominal tissues, while humoral immune pathways seem to have important antiviral activities. This analysis also broadens the definition of honey bee immune response by identifying genes encoding proteins, such as melittin and secapin, which have not been considered part of the canonical immune response. Using a gene co-expression analysis, we also identified potentially important mediators and regulators of anti-pathogen responses, including the Toll-pathway genes Serpin-5 and PGRP-S1, the JAK/STAT modulators Drk and Socs5, and the newly characterized kynurenine/alpha-aminoadipate aminotransferase (LOC724239) and an L-lactate dehydrogenase (LOC411188). Overall, our synthesis helps to pinpoint key host genes and pathways that respond to phylogenetically diverse pathogens. This gene list will likely be an important source for future functional studies and potentially for selecting more resilient honey bee stocks [23, 62]. More generally, the statistical and bioinformatics approaches developed in this study can be broadly applied to synthesize information across transcriptomic datasets to address a wide array of biological questions.

Methods

Dataset selection for meta-analysis

We restricted our analysis to microarrays and RNA-seq datasets obtained from experimentally infected honey bee workers (Table 2). In total, we collected 19 transcriptome datasets obtained from nine experiments, reporting the differential expression of transcripts between control bees and samples parasitized by Nosema spp., RNA virus and/or V. destructor and in which pathogen infection was a formal component of the experimental design (i.e. studies in which transcriptomes were generated for control and treatment groups). These 19 datasets were either from unpublished studies generated by the co-authors or recently published (and therefore publicly available) studies at the start of our work. Microarray probes and gene identifiers were converted or updated to the latest version of the honey bee genome assembly Amel_4.5 and its annotation from NCBI [63]. Differential gene expression data (treatment vs. control) were provided by authors of studies in terms of log2 fold changes.

The use of one dataset (#3 in Table 2) required the reprocessing of the original raw data. We retrieved the pre-processed tiling array expression data (GSE25455) from NCBI GEO as described by Dussaubat et al. [26]. We then re-annotated the probe sequences of the tiling array by alignment to Apis mellifera transcripts extracted from Amel_4.5 annotation as in Poeschl et al. [64]. We used the re-annotated probes to create sets of probes to measure the abundance of each transcript. We extracted the already computed log fold changes from the data files and applied quantile normalization. We used the new probe annotation to compute the median log2 fold change of all probes assigned to represent a transcript. We recovered log2 fold changes for 10,002 transcripts from three biological replicates.

Gene annotation

Genes were annotated with GO terms using Blast2GO [65]. The first step of sequence alignments was done in-house using BLAST [66]. The sequences of transcripts associated with gene identifiers from the honey bee genome assembly were recovered and compared to those in the non-redundant database [67] [downloaded on 2014/03/06, containing 35,149,712 sequences] using Blastx (parameters: e-value cutoff of 1E-6 and maximum number of alignments 20). Alignments were uploaded to the Blast2GO server and all following steps were done according to the Blast2GO pipeline using default settings. GoSlim-terms were chosen for annotation to reduce redundancy among overrepresented GO terms [68].

Selection of genes for inclusion in the analysis

We combined log2 fold expression values of 11,165 genes from the 19 transcriptome datasets in one full synthesised dataset (fsd) file. Due to the diversity of expression detection platforms and changes in gene annotation within recent years, 56% of the genes contained missing values in at least one transcriptome dataset; hence, only 44% of the genes with complete observation across the 19 datasets would remain for the analysis. Therefore, to increase the number of genes to include in our synthesis, we constructed a restricted synthesised dataset (rsd) with a subset of the fsd containing log2 fold expression values of 7,077 genes that had no more than three missing values (NAs) across the 19 transcriptome datasets. This enabled us to evaluate the expression changes of 63% of the annotated genes from the current genome assembly (see Additional file 1: Figure S7) and constituted the dataset for further analyses.

Statistical analysis of gene expression required complete observations of a gene across all 19 transcriptome datasets. To overcome missing data for genes with incomplete observations, we ordered gene expression values by their log2 fold change values and gave each a relative rank in each of the 19 transcriptome datasets. Relative ranks ranged between 1 for up-regulated genes and 0 for down-regulated genes. Missing values (5,015 of 134,463 in total) were then replaced by the average of non-missing relative ranks for the same gene from other datasets. We refer to this relative ranked dataset as ranked rsd, which is publicly available with the fsd at https://idata.idiv.de/DDM/Data/ShowData/35.

Multidimensional scaling analysis

We visualized the spread of the datasets by performing multidimensional scaling using the ranked rsd values from the differential expression values of the 7,077 genes across the 19 transcriptome datasets. We computed the Manhattan distances between each pair of transcriptome datasets using the cmdscale function of the stats R package [69].

Rank product analysis

Gene expression measurements using either microarrays or whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) vary greatly in methodology [70], resulting in substantial differences in the data produced. RNA-seq is generally more sensitive, producing gene expression levels spanning a greater dynamic range of values and resulting in a broad range of differential gene expression levels between control and infected samples (Additional file 1: Figure S8). In contrast, microarrays typically report lower differential gene expression.

To overcome this issue and compare a gene’s level of expression across different datasets regardless of its differential expression range, we performed a rank product analysis, a non-parametric statistic used for detecting differentially expressed genes based on (log) fold changes. The rank product analysis identifies genes that are consistently highly ranked in a number of datasets, and is a powerful approach to detect biologically relevant gene expression changes from heterogeneous datasets [41]. For this we used the RankProd R package [71], which accepts pre-processed expression datasets produced from different platforms, and thus was appropriate for our ranked rsd. In short, all 7,077 genes were ordered based on their relative ranks and were given ranks from 1 to 7,077 in each transcriptome dataset. From these new rank values the rank product was computed for each gene across the 19 transcriptome datasets and p-values were assigned to genes using a permutation test (N = 10,000) to test for differential expression. We then corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure from the multtest R package [72]. Using this approach, we identified genes that were (i) significantly up-regulated (genes with corrected rank product p-value < 0.05), (ii) genes significantly down-regulated (corrected p-value < 0.05), and (iii) genes significantly differentially-regulated regardless of the orientation (up-regulated in some studies, down in the others, and here termed differentially-regulated; corrected p-value < 0.05), across the 19 transcriptome datasets. For (i) and (ii) the ranked rsd was used to perform the analyses; note that a gene may be statistically significantly up-regulated across all 19 datasets by the rank product analysis but still be down-regulated in one or more datasets (and vice-versa for significantly down-regulated genes). For (iii) we transformed the data as follows: the log2 fold changes of each dataset were shifted by their median to obtain an equal amount of up- and down-regulated genes, to avoid biased analysis towards strongly up or down-regulated genes. Signs of the log2 fold changes were omitted and genes from group (iii) were first processed as described for the rsd, and then used to perform the analysis. Group (iii) therefore also contained genes of groups (i) and (ii).

This resulted in three lists of genes and their ranks in the 19 transcriptome datasets, their rank product value, p-value as well as corrected p-value. To test whether a specific GO term was significantly over- and under-represented in a specific gene set compared to a background set, we performed a two-sided Fisher’s exact test using the stats R package [69].

Gene evolutionary rates

We collected from the OrthoDB open source [33] the relative evolutionary rates, calculated from 12 bee genomes (Apis cerana, A. dorsata, A. florea, A. mellifera, Bombus impatiens, B. terrestris, Dufourea novaeangliae, Eufriesea mexicana, Habropoda laboriosa, Lasioglossum albipes, Megachile rotundata, and Melipona quadrifasciata), for 6,369 of the 7,077 genes contained in the rsd file (evolutionary rates of differentially expressed genes available in Additional file Tables). Relative evolutionary rates are quantified as the average of inter-species protein sequence identities normalized to the average identity of all inter-species orthologs. We compared the rates of genes with no significant changes in expression (N = 6,069) to the rates of genes in the three categories: differentially-regulated, up-regulated and down-regulated (N = 155, 49 and 96, respectively), using a Kruskal-Wallis tests and a Dunn’s test with Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-values for multiple pairwise comparisons.

Specific response to pathogens

To detect the specific response of honey bees to pathogens, we developed a novel method which applies the same rank product analysis as above, but on ranks that reflect the degree of similarity between a gene’s expression profile and a custom expression profile across the 19 datasets. In other words, we identified genes whose expression profile is most similar to a theoretical expression profile corresponding to selected parameters. We called this method DiRank, for directed rank product analysis (R code available at https://idata.idiv.de/DDM/Data/ShowData/35). For the current study, we identified genes that were specifically expressed in (i) abdominal tissues (i.e. gut, fat body or whole abdomens) after Nosema spp. infections (datasets #3-9, see Table 2) or (ii) in all tissues after RNA virus infection or Varroa parasitism, as mites transmit RNA viruses (datasets #12-19). We thereby designed theoretical gene expression profiles across the 19 datasets. As an example, to identify genes specifically regulated in abdominal tissues after Nosema infection, we designed two custom profiles, one profile of increased expression in abdominal tissues of Nosema infected bees, with no changes of expression levels in other datasets, and a second profile of decreased expression in abdominal tissues of Nosema infected bees, with no changes of expression levels in other datasets. In the ranked rsd file, differential expression thresholds was defined, such as genes with only slight expression changes, with relative ranks ranging from 0.3 to 0.7, were considered as non-differentially expressed and assigned a relative rank of 0.5. These thresholds reduced the impact of small variation in expression levels on the analysis.

We then subtracted the values of the custom profile from each of the 7,077 gene expression profiles, generating a differential profile for each gene. Genes with expression profiles similar to the custom profile received a majority of differential expression values of 0, while very dissimilar profiles tended towards values of 1 or −1. Absolute values were then subtracted from 1, and genes showing a similar profile to the custom profile tended to have values close to 1 and dissimilar profiles close to 0. Using the rank product approach, as thus described, we identified genes that significantly followed the custom profile. Figure 5 illustrates the method of the directed rank product applied here. In addition, the same analyses adapted for identification of the most dissimilar (i.e. opposite) profiles were performed (Additional file 1: Figure S9) to build a gene co-expression network (see below).

Methodological workflow of the directed rank product analysis (DiRank). This new method aims to identify genes with similar expression profile to a theoretical or observed profile of another gene. Gene expression values and profiles (geps) (shown in blue) and custom profile (cp) (shown in red), consisting of relative rank values, serve as input (yellow boxes). In rectangular matrices, gene expression values are reported in rows, while columns represent the transcriptome datasets. A custom profile can either be a user-defined profile or an existing gene expression profile. The directed rank product analysis aims to identify genes with a similar expression profile to the custom profile and to assign associated p-values. The custom profile is subtracted from each of the gene expression profiles and each difference (gep - cp) is transformed by 1 -| gep - cp|. Transformed gene expression values and corresponding profiles are shown in green in the grey box. These transformed gene expression values are then used as input data for a rank product analysis. As an example, the transformed gene expression values surrounded by an orange frame are ranked on top by the rank product analysis as the original gene expression profile was the most similar (before transformation) to the custom profile

All directed rank product analyses resulted in a list of genes annotated with their rank product values, their ranks according to the rank product value, p-value, corrected p-value, and ranks across the 19 transcriptome datasets. We used a cut-off uncorrected p-value < 0.01 to identify genes specifically regulated under the selected parameters (Nosema in abdominal tissues or Varroa/virus) and to identify the associated overrepresented GO terms.

Gene co-expression networks

Following an iterative process, we defined the expression profile of each gene as a custom profile for our DiRank method, so as to retrieve genes with similar expression across datasets, and the inverse of each gene profile (i.e. inverted) to identify genes with an opposite expression profile (see Additional file 1: Figure S9).

For each of the 7,077 genes from the ranked rsd file we obtained a list of other genes that showed a similar or an opposite expression profile. We then reconstructed the gene co-expression network using inter-gene connection falling under a Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p-value cut-off of 0.05, after permutation test (N = 1,000). We visualized the network using Cytoscape [73], with genes as the ‘nodes’ of the network and gene interactions as the ‘edges’ between nodes, while a ‘module’ is a subset of interconnect nodes. We defined highly connected genes as the top 5% most connected nodes, which we termed ‘hub genes’.

To identify novel candidate genes involved in immune regulation, we collected all interactions involving canonical immune genes based on the literature [35] (listed in Additional file 2: Table ST14).

Abbreviations

- Ago:

-

Argonaute

- AMP:

-

Antimicrobial peptide

- Apd:

-

Apidermin

- B-gluc1:

-

Beta-1,3-glucan recognition protein 1

- BQCV:

-

Black queen cell virus

- Def:

-

Defensin

- Drk:

-

Downstream of receptor kinase

- DWV:

-

Deformed wing virus

- EF1-alpha:

-

Elongation factor 1-alpha

- fsd:

-

Full synthesised dataset

- GMC:

-

Glucose-methanol-choline

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- iap2:

-

Inhibitor of apoptosis 2

- IAPV:

-

Israeli acute paralysis virus

- IMD:

-

Immunodeficiency

- IRP30:

-

Immune-responsive protein 30

- JAK/STAT:

-

Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription

- Lys:

-

Lysozyme

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Mrjp:

-

Major royal jelly proteins

- Mvl:

-

Malvolio

- NADH:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide H

- NF-kB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa B

- p.i.:

-

Post infection

- PGRP:

-

Peptidoglycan recognition proteins

- rel:

-

Relish

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- RNA-seq:

-

Ribonucleic acid sequencing

- rsd:

-

Restricted synthesised dataset

- Serpin:

-

Serine proteinase inhibitors

- Socs:

-

Suppressor of cytokine signalling

- SP:

-

Serine protease

- Vg:

-

Vitellogenin

References

Vivier E, Malissen B. Innate and adaptive immunity: specificities and signaling hierarchies revisited. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:17–21.

Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743.

Kurtz J. Specific memory within innate immune systems. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:186–92.

Sadd BM, Kleinlogel Y, Schmid-Hempel R, Schmid-Hempel P. Trans-generational immune priming in a social insect. Biol Lett. 2005;1:386–8.

Barribeau SM, Sadd BM, du Plessis L, Schmid-Hempel P. Gene expression differences underlying genotype-by-genotype specificity in a host-parasite system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3496–501.

Cremer S, Armitage SA, Schmid-Hempel P. Social immunity. Curr Biol. 2007;17:693–702.

Schmid-Hempel P. Parasites in social insects. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1998.

Barribeau SM, Sadd BM, du Plessis L, Brown MJF, Buechel SD, Cappelle K, et al. A depauperate immune repertoire precedes evolution of sociality in bees. Genome Biol. 2015;16:83.

Genersch E, Von Der Ohe W, Kaatz H, Schroeder A, Otten C, Büchler R, et al. The German bee monitoring project: a long term study to understand periodically high winter losses of honey bee colonies. Apidologie. 2010;41:332–52.

Evans JD, Schwarz RS. Bees brought to their knees: microbes affecting honey bee health. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:614–20. Elsevier Ltd.

Engel P, Kwong WK, McFrederick QS, Anderson KE, Barribeau SM, Chandler JA, et al. The bee microbiome: impact on bee health and model for evolution and ecology of host-microbe interactions. MBio. 2016;7:e02164–15.

Vanbergen AJ. Threats to an ecosystem service: pressures on pollinators. Front Ecol Environ. 2013;11:251–9.

Fries I. Nosema ceranae in European honey bees (Apis mellifera). J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;103:S73–9.

McMenamin AJ, Genersch E. Honey bee colony losses and associated viruses. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2015;8:121–9.

Nazzi F, Le Conte Y. Ecology of Varroa destructor, the major ectoparasite of the western honey bee, Apis mellifera. Annu Rev Entomol Annu Rev. 2016;61:417–32.

Martin SJ, Highfield AC, Brettell L, Villalobos EM, Budge GE, Powell M, et al. Global honey bee viral landscape altered by a parasitic mite. Science. 2012;336:1304–6.

Nazzi F, Brown SP, Annoscia D, Del Piccolo F, Di Prisco G, Varricchio P, et al. Synergistic parasite-pathogen interactions mediated by host immunity can drive the collapse of honeybee colonies. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002735.

McMahon DP, Natsopoulou ME, Doublet V, Fürst M, Weging S, Brown MJF, et al. Elevated virulence of an emerging viral genotype as a driver of honeybee loss. Proc Biol Sci. 2016;283:443–9.

Doublet V, Natsopoulou ME, Zschiesche L, Paxton RJ. Within-host competition among the honey bees pathogens Nosema ceranae and deformed wing virus is asymmetric and to the disadvantage of the virus. J Invertebr Pathol. 2015;124:31–4.

Natsopoulou ME, McMahon DP, Doublet V, Bryden J, Paxton RJ. Interspecific competition in honeybee intracellular gut parasites is asymmetric and favours the spread of an emerging infectious disease. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282:20141896.

Doublet V, Labarussias M, de Miranda JR, Moritz RFA, Paxton RJ. Bees under stress: sublethal doses of a neonicotinoid pesticide and pathogens interact to elevate honey bee mortality across the life cycle. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:969–83.

Brutscher LM, McMenamin AJ, Flenniken ML. The buzz about honey bee viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005757.

Grozinger CM, Robinson GE. The power and promise of applying genomics to honey bee health. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2015;10:124–32.

Doublet V, Paxton RJ, McDonnell CM, Dubois E, Nidelet S, Moritz RFA, et al. Brain transcriptomes of honey bees (Apis mellifera) experimentally infected by two pathogens: black queen cell virus and Nosema ceranae. Genomics Data. 2016;10:79–82.

McDonnell CM, Alaux C, Parrinello H, Desvignes J-P, Crauser D, Durbesson E, et al. Ecto- and endoparasite induce similar chemical and brain neurogenomic responses in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). BMC Ecol. 2013;13:25.

Dussaubat C, Brunet JL, Higes M, Colbourne JK, Lopez J, Choi JH, et al. Gut pathology and responses to the microsporidium Nosema ceranae in the honey bee Apis mellifera. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37017.

Holt HL, Aronstein KA, Grozinger CM. Chronic parasitization by Nosema microsporidia causes global expression changes in core nutritional, metabolic and behavioral pathways in honey bee workers (Apis mellifera). BMC Genomics. 2013;14:799.

Galbraith DA, Yang X, Niño EL, Yi S, Grozinger CM. Parallel epigenomic and transcriptomic responses to viral infection in honey bees (Apis mellifera). PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004713.

Flenniken ML, Andino R. Non-specific dsRNA-mediated antiviral response in the honey bee. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77263.

Boldrick JC, Alizadeh AA, Diehn M, Dudoit S, Liu CL, Belcher CE, et al. Stereotyped and specific gene expression programs in human innate immune responses to bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:972–7.

Jenner RG, Young RA. Insights into host responses against pathogens from transcriptional profiling. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:281–94.

Bartholomay LC, Waterhouse RM, Mayhew GF, Campbell CL, Michel K, Zou Z, et al. Pathogenomics of Culex quinquefasciatus and meta-analysis of infection responses to diverse pathogens. Science. 2010;330:88–90.

Kriventseva EV, Tegenfeldt F, Petty TJ, Waterhouse RM, Simão FA, Pozdnyakov IA, et al. OrthoDB v8: update of the hierarchical catalog of orthologs and the underlying free software. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D250–6.

Kuster RD, Boncristiani HF, Rueppell O. Immunogene and viral transcript dynamics during parasitic Varroa destructor mite infection of developing honey bee (Apis mellifera) pupae. J Exp Biol. 2014;217:1710–8.

Evans JD, Aronstein KA, Chen Y, Hetru C, Imler J-L, Jiang H, et al. Immune pathways and defence mechanisms in honey bees Apis mellifera. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:645–56.

Merkling SH, Overheul GJ, van Mierlo JT, Arends D, Gilissen C, van Rij RP, et al. The heat shock response restricts virus infection in Drosophila. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12758.

White JW, Subers MH, Schepartz AI. The identification of inhibine, the antibacterial factor in honey, as hydrogen peroxide and its origin in a honey glucose-oxidase system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;73:57–70.

Broderick S, Wang X, Simms N, Page-McCaw A. Drosophila Ninjurin A induces nonapoptotic cell death. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44567.

Helbing S, Lattorff HMG. Patterns of molecular evolution of RNAi genes in social and socially parasitic bumblebees. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;42:53–9.

Harpur BA, Zayed A. Accelerated evolution of innate immunity proteins in social insects: adaptive evolution or relaxed constraint? Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1665–74.

Breitling R, Armengaud P, Amtmann A, Herzyk P. Rank products: a simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. FEBS Lett. 2004;573:83–92.

Higes M, Juarranz Á, Dias-Almeida J, Lucena S, Botías C, Meana A, et al. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis of Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia: Nosematidae) in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:530–6.

Kurze C, Le Conte Y, Dussaubat C, Erler S, Kryger P, Lewkowski O, et al. Nosema tolerant honeybees (Apis mellifera) escape parasitic manipulation of apoptosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140174.

Arakane Y, Muthukrishnan S, Beeman RW, Kanost MR, Kramer KJ. Laccase 2 is the phenoloxidase gene required for beetle cuticle tanning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11337–42.

Fennell JF, Shipman WH, Cole LJ. Antibacterial action of melittin, a polypeptide from bee venom. Exp Biol Med. 1968;127:707–10. SAGE Publications.

Lee KS, Kim BY, Yoon HJ, Choi YS, Jin BR. Secapin, a bee venom peptide, exhibits anti-fibrinolytic, anti-elastolytic, and anti-microbial activities. Dev Comp Immunol. 2016;63:27–35.

Merkling SH, Van Rij RP. Beyond RNAi: Antiviral defense strategies in Drosophila and mosquito. J Insect Physiol. 2013;59:159–70.

Chen Y, Pettis JS, Corona M, Chen WP, Li CJ, Spivak M, et al. Israeli acute paralysis virus: epidemiology, pathogenesis and implications for honey bee health. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004261.

Di Prisco G, Annoscia D, Margiotta M, Ferrara R, Varricchio P, Zanni V, et al. A mutualistic symbiosis between a parasitic mite and a pathogenic virus undermines honey bee immunity and health. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:3203–8.

Lavine MD, Strand MR. Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1295–309.

Bronkhorst AW, Van Rij RP. The long and short of antiviral defense: Small RNA-based immunity in insects. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;7:19–28.

Brutscher LM, Daughenbaugh KF, Flenniken ML. Antiviral defense mechanisms in honey bees. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2015;10:71–82.

Boncristiani HF, Evans JD, Chen Y, Pettis J, Murphy C, Lopez DL, et al. In vitro infection of pupae with Israeli acute paralysis virus suggests disturbance of transcriptional homeostasis in honey bees (Apis mellifera). PLoS One. 2013;8:e73429.

Corona M, Velarde RA, Remolina S, Moran-Lauter A, Wang Y, Hughes KA, et al. Vitellogenin, juvenile hormone, insulin signaling, and queen honey bee longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7128–33.

Salmela H, Amdam GV, Freitak D. Transfer of immunity from mother to offspring is mediated via egg-yolk protein vitellogenin. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005015.

Marco Antonio DS, Guidugli-Lazzarini KR, do Nascimento AM, Simões ZLP, Hartfelder K. RNAi-mediated silencing of vitellogenin gene function turns honeybee (Apis mellifera) workers into extremely precocious foragers. Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95:953–61.

Ben-Shahar Y, Dudek NL, Robinson GE. Phenotypic deconstruction reveals involvement of manganese transporter malvolio in honey bee division of labor. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3281–8.

Natsopoulou ME, McMahon DP, Paxton RJ. Parasites modulate within-colony activity and accelerate the temporal polyethism schedule of a social insect, the honey bee. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2016;70:1019-31.

Barribeau SM, Schmid-Hempel P, Sadd BM. Royal decree: gene expression in trans-generationally immune primed bumblebee workers mimics a primary immune response. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159635.

Kleino A, Myllymäki H, Kallio J, Vanha-aho L-M, Oksanen K, Ulvila J, et al. Pirk is a negative regulator of the Drosophila Imd pathway. J Immunol. 2008;180:5413–22.

Tran TA, Kinch L, Peña-Llopis S, Kockel L, Grishin N, Jiang H, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inactivation by sunitinib results in Tsc1/Tsc2-dependent inhibition of TORC1. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:3762–79.

Niño EL, Jasper WC. Improving the future of honey bee breeding programs by employing recent scientific advances. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2015;10:163–9.

Elsik CG, Worley KC, Bennett AK, Beye M, Camara F, Childers CP, et al. Finding the missing honey bee genes: lessons learned from a genome upgrade. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:86.

Poeschl Y, Delker C, Trenner J, Ullrich KK, Quint M, Grosse I, et al. Optimized probe masking for comparative transcriptomics of closely related species. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78497.

Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–6.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10.

Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequence (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D501–4.

Gene Ontology Consortium. The gene ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D258–61.

R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna R Found. Stat. Comput. Available http://www.R-project.org. 2014.

Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63.

Hong F, Wittner B. RankProd: Rank Product method for identifying differentially expressed genes with application in meta-analysis. R Packag. version 2.38.0. 2011.

Pollard KS, Dudoit S, van der Laan MJ. Multiple testing procedures: the multtest package and applications to genomics. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Edited by: Gentleman R, Carey V, Huber W, Irizarry R, Dudoit S.; Springer, 2005. p. 251-72.

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–504.

Raw data available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/experiments/E-MTAB-5508/.

Raw data available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/experiments/E-MTAB-5070/.

Raw data available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE94855.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexander Gabel for performing the blast search, and Laura Brutscher and Alexander McMenamin for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments which have helped improve the manuscript.

Funding

This article is a joint effort of the working group TRANSBEE and an outcome of two workshops kindly supported by sDiv, the Synthesis Centre for Biodiversity Sciences within the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig, funded by the German Science Foundation (FZT 118). New datasets were performed thanks to the Insect Pollinators Initiative (IPI grant BB/I000100/1 and BB/I000151/1), with participation of the UK-USA exchange funded by the BBSRC BB/I025220/1 (datasets #4, 11 and 14). The IPI is funded jointly by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, the Natural Environment Research Council, the Scottish Government and the Wellcome Trust, under the Living with Environmental Change Partnership. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Microarray expression data have been deposited on ArrayExpress (Archive of Functional Genomics Data from the European Bioinformatics Institute) under accession numbers E-MTAB-5508 (datasets #4, 11 and 14), and E-MTAB-5070 (#13). RNA-sequencing data (datasets #18 and 19) have been deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus repository, under the accession number GSE94855.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the analyses: VD, YP, AGD, CeA, ChA, SMB, OCBR, MJFB, JCB, MLF, EG, IG, HLH, DH, HMGL, YLC, FM, DPM, RFAM, FN, ELN, KN, RPvR, RJP, CMG. Performed and analysed new transcriptomes: DA, DAG, EG, SG, DPM, FN, ELN, RJP, CMG. Performed the meta-analysis: VD, YP, AGD, RJP, CMG. Wrote the paper: VD, YP, AGD, RJP, CMG. Commented on the manuscript: CeA, ChA, SMB, OCBR, MJFB, JCB, MLF, EG, IG, HLH, DH, HMGL, YLC, FM, DPM, RFAM, FN, ELN, KN, RPvR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All animals used in experiments reported in this work were obtained in Germany and Italy, and no ethical permits are required in these countries to carry out research on insects. Therefore, all procedures were conducted according to the ethical guidelines of Germany and Italy to ensure ethical appropriateness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Robert J. Paxton and Christina M. Grozinger are co-last authors.

The original version of this article was revised: to remove two additional red lines that appeared in figure 5.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-3624-7.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1-S9.

This file includes supplementary figures documenting our multidimensional scaling analysis results, a heat map of the differential expression of the 7,077 genes across the 19 datasets, a Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes, the expression profile of the gene coding for hymenoptaecin, the distribution of genes according to their number of inter-gene connections, the degree of connectivity of differentially expressed genes, the process of gene selection for this study, the distribution of genes’ differential expression across datasets, and a diagram illustrating our new bioinformatics approach. (PDF 683 kb)

Additional file 2: Table ST1.

List of 7,077 genes ordered by their rank product after the rank product analysis looking for up-regulated genes. Genes ordered from higher ranks (up-regulated) to lower ranks (non-regulated). Table ST2. List of 7,077 genes ordered by their rank product after the rank product analysis looking for down-regulated genes. Genes ordered from higher ranks (down-regulated) to lower ranks (non-regulated). Table ST3. List of 7,077 genes ordered by their rank product after the rank product analysis looking for differentially-regulated genes. Genes ordered from higher ranks (differentially-regulated) to lower ranks (non-regulated). Table ST4. List of 7,077 genes ordered by their rank product after the directed rank product analysis looking for up-regulated genes in abdominal tissue, after Nosema infection. Table ST5. List of 7,077 genes ordered by their rank product after the directed rank product analysis looking for down-regulated genes in abdominal tissue, after Nosema infection. Table ST6. Functional analysis (GO slim) based on top up-regulated genes in abdominal tissues (gut, fat body or all abdomen) upon infection by Nosema. Cut-off < 0.01 uncorrected p-value, genes from S4 Table. Table ST7. Functional analysis (GO slim) based on top down-regulated genes in abdominal tissues (gut, fat body or all abdomen) upon infection by Nosema. Cut-off < 0.01 uncorrected p-value, genes from S5 Table. Table ST8. List of 7,077 genes ordered by their rank product after the directed rank product analysis looking for up-regulated genes after RNA virus infection and Varroa infestation. Table ST9. List of 7,077 genes ordered by their rank product after the directed rank product analysis looking for down-regulated genes after RNA virus infection and Varroa infestation. Table ST10. Functional analysis (GO slim) based on top up-regulated genes upon infection by RNA virus and Varroa infestation. Cut-off < 0.01 uncorrected p-value, genes from S8 Table. Table ST11. Functional analysis (GO slim) based on top down-regulated genes upon infection by RNA virus and Varroa infestation. Cut-off < 0.01 uncorrected p-value, genes from S9 Table. Table ST12. List of the 209 highly connected (hub) genes with at least 34 inter-gene connections. Table ST13. List of genes involved in the immune gene network (Fig. 4C). Table ST14. List of immune genes used to construct the immune gene network (Fig. 4C). Table ST15. Experimental procedure and description of datasets. (XLSX 9947 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Doublet, V., Poeschl, Y., Gogol-Döring, A. et al. Unity in defence: honeybee workers exhibit conserved molecular responses to diverse pathogens. BMC Genomics 18, 207 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-3597-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-3597-6