Abstract

Background

Varroa mites are widely considered the biggest honey bee health problem worldwide. Until recently, Varroa jacobsoni has been found to live and reproduce only in Asian honey bee (Apis cerana) colonies, while V. destructor successfully reproduces in both A. cerana and A. mellifera colonies. However, we have identified an island population of V. jacobsoni that is highly destructive to A. mellifera, the primary species used for pollination and honey production. The ability of these populations of mites to cross the host species boundary potentially represents an enormous threat to apiculture, and is presumably due to genetic variation that exists among populations of V. jacobsoni that influences gene expression and reproductive status. In this work, we investigate differences in gene expression between populations of V. jacobsoni reproducing on A. cerana and those either reproducing or not capable of reproducing on A. mellifera, in order to gain insight into differences that allow V. jacobsoni to overcome its normal species tropism.

Results

We sequenced and assembled a de novo transcriptome of V. jacobsoni. We also performed a differential gene expression analysis contrasting biological replicates of V. jacobsoni populations that differ in their ability to reproduce on A. mellifera. Using the edgeR, EBSeq and DESeq R packages for differential gene expression analysis, we found 287 differentially expressed genes (FDR ≤ 0.05), of which 91% were up regulated in mites reproducing on A. mellifera. In addition, mites found reproducing on A. mellifera showed substantially more variation in expression among replicates. We searched for orthologous genes in public databases and were able to associate 100 of these 287 differentially expressed genes with a functional description.

Conclusions

There is differential gene expression between the two mite groups, with more variation in gene expression among mites that were able to reproduce on A. mellifera. A small set of genes showed reduced expression in mites on the A. mellifera host, including putative transcription factors and digestive tract developmental genes. The vast majority of differentially expressed genes were up-regulated in this host. This gene set showed enrichment for genes associated with mitochondrial respiratory function and apoptosis, suggesting that mites on this host may be experiencing higher stress, and may be less optimally adapted to parasitize it. Some genes involved in reproduction and oogenesis were also overexpressed, which should be further studied in regards to this host shift.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) are the most important insect for pollination of crops and wildflowers [1–3], but they have experienced increasing colony die-offs during the past two decades [4–6]. Varroa destructor is widely considered the most serious risk factor for honey bee colony mortality worldwide [7–10]. These large ectoparasitic mites are associated with a condition known as parasitic mite syndrome (PMS), or “Varroosis”. In colonies exhibiting PMS or “Varroosis”, pathogens, including brood diseases and viruses, are present at unusually high levels [11–13]. Varroa mites feed on the hemolymph of the larva, pupa and adults, and the open wounds caused by mite feeding can allow microorganisms to enter and weaken the host [14]; Mites themselves are vectors for viruses and perhaps other bee pathogens [13]. The Varroa mite’s life cycle consists of two phases, the phoretic phase, during which the adult female mite lives, feeds, and disperses on the adult bee, and the reproductive phase in which the female mite feeds and reproduces inside the sealed brood cell of the pupating honey bee [15]. After a female mite invades the brood cell, the first egg laid will develop into a haploid male, which will later mate with his sisters (unless two females invade the same cell) to give rise to the next generation. The most common Varroa-associated viral infection is deformed wing virus (DWV). The incidence of DWV is closely associated with mite infestation and colony mortality, but other bee-pathogenic viruses such as acute bee paralysis virus have also been identified as part of the “Varroosis” [15, 16]. Failure to treat infested colonies with miticides typically results in colony death within 1–3 years.

V. destructor was originally a parasite of the Asian honey bee, Apis cerana. At least 60 years ago, it made a host switch and now parasitizes several European and African races of A. mellifera [17]. Population studies indicate that there was a genetic bottleneck associated with the host switch to A. mellifera [18–20]. These studies revealed a remarkable absence of heterozygosity in the Varroa populations of Europe and USA collected on A. mellifera [21–23]. Furthermore, a study using microsatellite markers in 45 different populations of Varroa mites from around the world showed a relative lack of polymorphisms within each of the two V. destructor mitochondrial haplotypes, Japan (J) and Korea (K), that successfully infest A. mellifera outside of Asia. These results suggested that these two haplotypes, J and K, each correspond to a single host capture event, followed by a rapid spread, particularly by K, which has now almost spread worldwide. These haplotypes also seem to be completely reproductively isolated from each other. Two routes of invasion of V. destructor into the Americas, and specifically into the USA, have been proposed based on the dates and places where each haplotype was first detected [18–20]. The J haplotype first shifted from A. cerana to A. mellifera in Japan during the last century, following the introduction of A. mellifera. From Japan, it spread to Thailand, to Paraguay in (1971), to Brazil in 1972, and was later found in North America in 1987. The K haplotype first shifted from A. cerana to A. mellifera near Vladivostok (north of the Korean peninsula), following the introduction of A. mellifera from Ukraine in the 1950s. Later, it spread from eastern Russia to western Russia, to Bulgaria in 1972, to Germany in 1977, and then continued spreading around Europe and also to the U.S.

Other haplotypes of V. destructor as well as haplotypes of a sister species, V. jacobsoni, are reportedly restricted to A. cerana and only reproduce on drone brood in this species. All of these Varroa mites routinely invade sympatric non-host colonies and enter the drone and worker brood, but for unknown reasons do not produce offspring, perhaps as a result of failure to recognize host signals to initiate reproduction. Single V. jacobsoni female mites with dead immature offspring were found inside A. mellifera drone brood cells in Papua New Guinea (PNG) in 1991 and 1993, and these single events were reported in 1994 [24]. Recently, a population of V. jacobsoni was found reproducing on A. mellifera drone and worker brood, and was associated with colony mortality in PNG [25]. Evidence suggests that this host switch occurred by mites first gaining the ability to reproduce on drone brood, followed by adaptation to reproduce on worker brood. Since V. destructor has caused widespread losses wherever it has become established, it is important to study the V. jacobsoni host switch to A. mellifera to gain understanding of the evolutionary host shift from the Asian to the European honey bee. In addition, it is important to understand how this mite has become established, whether host-parasite signaling may be involved, and what cues may be associated with alterations in mite reproduction.

It is reasonable to expect that Varroa mites must change their gene expression in order to grow and reproduce in a different host species. As a first step, to understand the evolutionary host shift of Varroa mites to a new host, we have studied the transcriptome profile of V. jacobsoni reproducing on A. mellifera and compared it to that of V. jacobsoni restricted to reproducing on A. cerana.

Methods

Sample collection

A total of nine samples of V. jacobsoni from PNG and the Solomon Islands (Table 1) were collected from either A. cerana or A. mellifera drone brood cells during April 2010. When collected, their reproductive status (reproducing or not reproducing) was recorded. V. jacobsoni reproducing on A. mellifera were collected from Goroka, PNG, and will be referred in the rest of this paper as (Am-reproductive). Samples collected from St. Christobel Island (SC) and Ugi Island in the Solomon Islands were mites that were reproducing on A. cerana and will be referred in the rest of this paper as (Ac-reproductive). In addition, single adult females from A. mellifera colonies on SC and Ugi Island in Solomon Islands were found in brood cells but were not reproducing (mite offspring were not present) and will be referred in the rest of this paper as (Am-non-reproductive). It had been previously noted that over the previous 3 years mites on SC and Ugi Island could not reproduce on either worker or drone brood after spreading from sympatric A. cerana. All samples were collected in RNAlater® and stored at -80 °C until RNA extraction.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Pools of adult female mites from each sample were ground in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted using the Invitrogen TRIzol® reagent protocol with one exception; the RNA precipitation step was slightly modified by the addition of 250 μl of RNA precipitation solution (1.2 M NaCl + 0.8 M Sodium citrate dihydrate) mixed with 250 μl of isopropanol to the aqueous phase of the mite homogenate to help precipitate more RNA. Approximately 20 mites per sample were used for extraction, except for the non-reproducing mite sample for which only five non-reproducing mites were available for sequencing and RNA from all 5 mites was pooled. Total RNA per sample was then assessed for quality using a NanoDrop 2000/2000c (Thermosceintific) and submitted to the Purdue University Genomics Core Facility (PGCF) for sequencing. Total RNA was further analyzed for quality and concentration using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc. Santa Clara. CA). Seven out of nine cDNA libraries were prepared and barcoded by PGCF using the TruSeq™ RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, Inc. San Diego, CA). These libraries were prepared and sequenced at two different time points (April 2012 and January 2013) using the Illumina HiScanSQ (100 b paired-end reads, two lanes) and Hiseq2000 (100 b paired-end reads, 4 lanes) systems, respectively (Table 1). The remaining two cDNA libraries were prepared and sequenced using a Hiseq2000 (100 b paired-end reads, one lane) at the Biomolecular Resource Facility (BRF), Canberra, Australia (February 2014). Raw sequence reads from all 9 samples were then analyzed together.

Read pre-processing

Viral, bacterial, mitochondrial, and ribosomal RNA sequences were removed from the raw reads using the DeconSeq v 0.4.3 software [26], in order to focus on transcripts originating from the nuclear genome. “Contaminant” libraries were created by downloading all sequences in each corresponding category from the NCBI database. The viral library contained a total of 30,300 sequences of complete viral genomes. The bacterial library contained 2,451,824 complete genomic sequences. The mitochondrial library contained the complete sequence of V. destructor mitochondrial genome and the ribosomal RNA library contained 28,314 sequences including V. destructor 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA sequences. Remaining decontaminated reads were checked for duplicates, and adapters removed using in-house Perl scripts. Sequence quality was assessed using FastQC (v 0.10.0, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and quality trimming was performed using Trimmomatic v 0.30 [27], trimmomatic SE -phred33 ILLUMINACLIP:adapters.fa:2:35:15 LEADING:7 TRAILING:7 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:13 MINLEN:30 (Table 1). Because the reads were independently quality trimmed, some reads were unpaired after quality trimming and application of the minimum length cut off (30 bases).

Transcriptome assembly

A hybrid transcriptome assembly was created using all the paired and unpaired reads from the nine sequenced samples (BioProject: PRJNA321056, SRA: SRP075576). In order to create this hybrid assembly, two different transcriptome assemblies were created first, using the software Trinity (trinity_beta_Jan28_2014) [28], and then these two assemblies were merged using the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments (PASA; v pasa_r20130907) [29]. A de novo transcriptome assembly was created using Trinity default parameters (kmer length = 25, min_contig_length = 200 nucleotides). An independent genome guided assembly was created using (Trinity --genome_guided_max_intron 11000); using as a reference a draft of the genome of V. destructor (Jay Evans personal communication, December 2013). For this assembly, an in silico normalization of the full data set was performed using Trinity (normalize_by_kmer_coverage.pl --max_cov 50) in order to minimize the CPU running time. Finally, we created the hybrid transcriptome assembly by merging the de novo and genome-guided assemblies using PASA (default parameters). The numbers of sequences per assembly reported in this paper differ slightly from the transcriptome assemblies deposited to DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank (de novo transcriptome accession: GETM00000000, genome guided assembly accession: GETO00000000 and trinity/PASA hybrid transcriptome accession: GETP00000000) due to transcripts removed during NCBI curation process.

Description of a gene according to Trinity

Since a high quality genome assembly is available for neither V. jacobsoni nor V. destructor, it is important to carefully define what we mean by a gene. For de novo assemblies, Trinity reports many predicted transcripts, which are generated by combining all the splice junctions observed in the data; some of these predicted isoforms are not observed experimentally. In the first stage of Trinity reads are clustered according to their sequence overlap into components. Components are further divided into subcomponents and predicted isoforms. The concept of a gene most closely matches the component level as determined by BLAST comparisons (data not shown), therefore we performed differential expression (DE) analysis at the component level. In the genome guided assembly, genes are grouped according to their alignment to the reference genome. Each group then is independently assembled using the de novo Trinity assembly process. In the PASA hybrid assembly, de novo assemblies that do not match to the genome guided assembly are reported with their original Trinity component IDs, and de novo assemblies that match the genome guided assembly are merged with the genome guided assembly and combined into PASA assembly clusters (genes) based on exon overlap. Therefore in our analyses a gene indicates a Trinity component, or a PASA assembly cluster.

Assessing quality of the assembly

To assess the quality of the final assembled transcripts, all RNASeq cleaned reads were aligned back to the hybrid assembly using Bowtie2 [30] and overall mapping statistics were examined. In addition, to evaluate the completeness of the transcriptome assembly, the CEGMA (Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach), [31] software was applied to identify the presence of a core protein set consisting of 248 highly conserved proteins that are found in a wide range of eukaryotes.

Assembly annotation

A comprehensive automated functional annotation of the final hybrid assembled transcripts was performed using Trinotate (Transcriptome Functional Annotation and Analysis, [32]. Trinotate makes use of a number of comprehensive annotation databases for functional annotation including homology searches of sequence data (NCBI-BLAST), protein domain identification (HMMER/PFAM), protein signal prediction (siganlP/tmHMM), and comparison to other databases (EMBL UniProt/Swissprot eggNOG/GO pathways). To annotate the assembled transcripts, we also conducted a complete Blastx similarity search against the UniProt/Swissprot protein database, predicted peptides (20,486 sequences/descriptions as of August 22, 2014) of the deer tick Ixodes scapularis, with an E-value cutoff of ≤ 1e-06, and predicted peptides (11,767 sequences/descriptions as of November 6, 2014) of the mite Metaseiulus occidentalis.

Differential expression analysis

Quantification of the assembled transcripts was performed using standalone RSEM [33] which evaluates transcript abundances by mapping the RNAseq reads to the assembled transcriptome using the aligner tool Bowtie2. Only the reads from eight samples were mapped back to the assembled transcriptome, five samples were from pooled mites that were reproducing in the A. mellifera host from PNG, and three samples of pooled mites were reproducing in the A. cerana host from the Solomon Islands. Briefly, RSEM calculates posterior mean estimates, 95% credibility intervals, and maximum likelihood abundance estimates or expected counts (EC) for genes and predicted transcripts.

Identifying consistently differentially expressed mite genes CDEG

Expected counts per gene per sample were combined into a count matrix, and this matrix was used as input for all downstream expression analyses. These analyses were performed using three different R packages EBSeq, EdgeR and DESeq2 [34–36]. All differentially expressed genes that were common among the three methods, using a False Discovery Rate (FDR) ≤ 0.05, were extracted and used for downstream analyses. We refer to these genes as consistently differentially expressed genes (CDEG).

EdgeR is a Bioconductor-R package used to call differentially expressed genes from read counts obtained from RNA-Seq [36]. EdgeR was used to normalize the EC (obtained from RSEM) for relative expression and effective library size using the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) normalization method. Genes with at least 0.18 counts per million (CPM), which corresponds to 14 read counts per gene, in at least three samples were selected for further differential expression analysis. Differentially expressed genes (DEG) with FDR ≤ 0.05 and log fold change (logFC) of two were extracted.

The DESeq2 v. 1.0.19 [34] Bioconductor-R package was also used to call differentially expressed genes. DESeq2 implements a negative binomial based model. Before performing the DE analysis, DESeq2 automatically performs independent filtering of the genes with low counts (weakly expressed) in order to maximize the number of DEG with adjusted P-values less than a critical value of 0.1. For the differential expression analysis, genewise dispersions were estimated and DEG with FDR ≤ 0.05 and a logFC of two were extracted.

EBSeq v 1.4.0 is a Bioconductor-R package that uses empirical Bayesian methods to identify differentially expressed genes [35]. EBSeq estimates the posterior probability of being differential expressed (PPDE). A list of DE genes with a FDR controlled at α was extracted using a PPDE value greater than 1–α, where α was set to 0.05. By default EBSEq removes transcripts for which fewer than 75% of the samples have greater than 10 counts.

Heatmap and gene clustering

To generate heatmaps and gene clustering, we used the R packages EdgeR and heatmap3. FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase per Million) values obtained from RSEM for each of the CDEG were normalized and log2 transformed prior to gene clustering. CDEG were clustered according to their patterns of differential expression (correlation distance) using complete linkage clustering. In addition, we used the Trinity script (define_clusters_by_cutting_tree.pl –-Ktree 5). Plots of the expression patterns for the CDEG were generated using a modified version of the Trinity script (plot_expression_patterns.pl).

GO enrichment analyses of the CDEG

The 37,661 genes that passed the CPM cutoff used in EdgeR were further analyzed using Blast2GO [37] to assign gene ontology (GO) terms to each transcript. Predicted transcripts/genes were compared to the NCBI non-redundant database using Blastx. We retained the best hit for each gene with an E-value ≤ 1e-06. Blast2GO and GO enrichment analysis was performed for each CDEG cluster, using the target genes (37,661) as the reference set, and the individual gene clusters as test sets. A P-value cutoff of 0.1 was used for GO enrichment test.

Results

Varroa jacobsoni assembled transcriptome

V. jacobsoni mite samples were collected from two different honey bee hosts, A. cerana and A. mellifera, and from two different geographic locations, the Solomon Islands and PNG, respectively (Table 1). A total of nine RNAseq libraries were constructed and sequenced using two Illumina sequencing platforms (Table 1), yielding a total of 2.18 billion paired-end reads (1.09 billion paired-end fragments) see Table 2.

After pre-processing of the raw reads, a total of 592 million contaminant (viral, bacterial, mitochondrial and rRNA) reads (27%) and 26.7 million (1.2%) reads with adapters were removed from the raw data set. Furthermore, a total of 36.1 million (1.6%) reads with low quality were removed, leaving a total of 1.53 billion reads (70%) that were used for the transcriptome assemblies (Table 2). Three different transcriptome assemblies were created using Trinity/PASA as described in methods, see Fig. 1 for a detailed workflow). The final hybrid assembly produced a total of 319,231 putative transcripts and 223,620 putative genes (N50 = 3549 bp). The numbers reported here are before transcriptome assembly was deposited to DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank (this transcriptome shotgun assembly project has been deposited under the accession GETP00000000, this version here is the first version, GETM01000000). It is well known that the de novo transcriptome assemblers predict many more transcripts than are actually present due to the difficulty in predicting complete isoforms from short reads [38, 39]. In the quality analysis below, all predicted transcripts were used – the results are therefore reported in terms of the coverage of the reference sequences. In the subsequent gene expression analysis, all predicted transcript isoforms of each gene are combined, so the overprediction of isoforms is not an issue.

Transcriptome assembly and differentially expressed genes. Pipeline steps followed to build the assembly and expression profiles using 3 different R packages (EBSeq, EdgeR and DESeq2). Flow chart shows the steps implemented from raw reads to the selection of the final hybrid assembly and the selection of the consistently differentially expressed mite genes (CDEG)

Assessing the quality of the assembly

The details of the three assemblies as described in methods are shown in Table 3. The quality and completeness of our hybrid V. jacobsoni transcriptome assembly was assessed in four different ways: using CEGMA [31], by comparison with predicted gene sequences of the tick I. scapularis and the predatory mite M. occidentalis [40], and by aligning the cleaned reads back to the hybrid assembly.

Analysis of our hybrid assembly against the CEGMA protein set identified 246 out of 248 core proteins (99.2%) as complete (defined as > 70% alignment length versus the core protein) see Table 4. Furthermore, an average of about three V. jacobsoni assembled transcripts (perhaps representing 3 splice variants) aligned with each core protein, with 221 of those detected having more than 1 alignment (Table 5). We compared the hybrid assembly against the UniProt/Swissprot database using Blastx (hits with E-value ≤ 1e-06) and identified 4957 proteins represented by nearly full-length transcripts, having > 80% alignment coverage, and 8372 proteins having > 50% alignment coverage. In addition, we compared the hybrid assembly against the I. scapularis and the M. occidentalis predicted peptides database, using Blastx (E-value ≤ 1e-06). From the search against the I. scapularis database we found 3957 proteins that are represented by nearly full-length transcripts, having > 80% alignment coverage, and 5925 proteins having > 50% alignment coverage, which represents ~29% of the deer tick predicted peptides. Furthermore, from the search against the M. occidentalis database we found 5362 proteins that are represented by nearly full-length transcripts, having > 80% alignment coverage, and 7063 proteins having > 50% alignment coverage, which represents 60% of the total predatory mite predicted peptides. Cleaned reads for each sample were mapped back to the hybrid reference assembly using Bowtie2. Overall 95.6% of reads aligned to the reference indicating that almost all reads are represented in the assembly (Table 2). In summary, the V. jacobsoni transcriptome assembly contains a good representation of the core eukaryotic genes (CEGs), and a large portion of the reference peptides from related genera are represented in the mite transcriptome as substantially complete transcripts, together suggesting that the transcriptome described here is relatively complete.

Annotation of the assembly at transcript and gene levels

The hybrid transcriptome assembly of V. jacobsoni was used to query entries described in the UniProt/Swissprot protein database, using Blastx (E-value ≤1e-06). Only the most significant hit for each predicted transcript was retained. At the transcript level we found that 51,025 (~16%) out of 319,231 predicted transcripts have a match to a protein sequence, and 2870 (~6%) of those matches have a sequence identity ≥ 90%. These numbers seem very reasonable; alternatively spliced predicted transcripts are expected to have more than one match.

At the gene level we found 24,128 out of 223,620 putative genes have a match to a protein sequence and 2413 (10%) of them have a sequence identity ≥ 90%. Furthermore, when we compared the hybrid transcriptome assembly of V. jacobsoni against the I. scapularis database, which contains 20,486 unique predicted peptides, we found that 21,333 (~9%) of the V. jacobsoni genes, had a significant hit to a protein sequence in the deer tick database (E ≤ 1e-06). On the other hand, these 21,333 blast hits covered only 7629 (37.3%) of the predicted peptides of the deer tick. When we compared it against the M. occidentalis predicted peptides (11,767 unique sequences), we found that only 23,779 (~11%) of the V. jacobsoni genes had a significant hit to a protein sequence in the predatory mite (E ≤ 1e-06). However, these 23,779 blast hits covered 8388 (~71%) of the predicted peptides of the predatory mite. These results are expected if we consider that these two mites species are taxonomically classified under the same Mesostigmata order.

Differential expression analysis of mites reproducing on A. cerana and mites reproducing on A. mellifera

Quantification of the assembled transcripts was performed using standalone RSEM. Transcript abundances were evaluated by mapping the RNA-Seq cleaned reads to the assembled hybrid transcriptome using the aligner tool Bowtie2. The transcript abundance distribution looks very similar for all samples, indicating the data are suitable for differential expression analysis (see Additional file 1; Figure S1, histograms distribution).

To identify differentially expressed genes we used three different R packages as described in methods. Only eight of the nine mite samples were included in differential expression analysis; We chose not to include the Am-non-reproductive mite sample, because we did not have a biological replicate, and the reproductive status of the adult females was not the same as in the other eight samples. In addition, the number of reads obtained during sequencing was lower than for the rest of samples (Table 2).

After removing genes with low counts using EdgeR, we evaluated 37,661 genes for differential expression. We focused on those genes that were differentially expressed according to all three methods (EBSeq, EdgeR and DESeq2) in order to have a conservative set of consistently differentially expressed genes (CDEG) Fig. 1. EdgeR identified 1013 differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05 and absolute logFC ≥ 2; see Additional file 2; Table S1). In addition, using DESeq2 and EBSeq we identified a total of 586 and 6809 DEG (FDR < 0.05), respectively (see Additional file 3; Table S2 and Table S3). A total of 287 CDEG common to all three methods were extracted and further analyzed (Fig. 1). Out of the 287 CDEG, we found a total of 23 down-regulated genes and 264 up-regulated genes in the mites reproducing in the A. mellifera host as compared to mites on the A. cerana host.

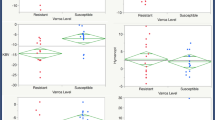

We grouped the genes according to expression pattern using correlation distances between genes and complete linkage clustering. Originally five gene clusters were generated, however, based on visual inspection of the pattern of expression we manually clustered the CDEG into three groups (Fig. 2). Cluster one contains 23 CDEG that were down-regulated in mites reproducing on the A. mellifera host. Cluster two contains 208 CDEG; differences in expression of genes in this cluster are not clearly correlated with the host on which the mite was reproducing. Cluster three contains 56 genes that were up-regulated in all mites reproducing on the A. mellifera host. Although generally up-regulated in the A. mellifera host, genes in clusters two and three showed clear differences in their pattern of expression across samples (Fig. 2). For example, in cluster two we observed that four samples (three A. cerana samples plus one A. mellifera sample) showed consistent low expression patterns across all 208 mite genes, while the other four A. mellifera samples showed higher expression patterns. However, cluster 3 showed more consistent up-regulation of mite genes across all A. mellifera samples.

Heatmap and gene clusters of CDEMG genes for V. jacobsoni mites. Heatmap of expression values (log2 transformed normalized FPKM) of the CDEMG adult female V. jacobsoni mites reproducing in A. cerana and A. mellifera. Orange and turquoise blue indicate higher and lower expression values, respectively. Red and blue tick bars indicate the A. cerana host and A. mellifera host respectively

GO terms assignment and Enrichment analysis

We used Blast2GO to assign GO terms to the 287 CDEG, and to test whether certain biological functions or GO terms are more frequently observed in the gene clusters, we used the Fisher exact test in Blast2GO to compare the GO terms of the CDEG in each of the gene clusters versus those in the complete transcriptome (reference set of 37,661 genes) each gene was represented by the highest Blastx hit and a P-value 0.1 was used for the Fisher exact test, see (Additional file 4; Table S4).

Cluster 1 CDEG down-regulated in A. mellifera

We found 23 CDEG that were specifically down-regulated in mites reproducing on the A. mellifera host. However, GO terms could be assigned for only two of these genes. The GO terms associated with these genes are related to digestive tract development and transcription factors (Table 5). For the full report of all the GO terms and the 36 unique GO-ID associated with cluster 1 genes, see Additional file 5: Table S5. Furthermore, only 5 of the 23 genes had a significant Blastx similarity hit (E-value ≤ 1e-06) to the M. occidentalis predicted peptides (see Additional file 6: Table S6) and only 3 out the 23 genes had significant Blastx similarity hits (E-value ≤ 1e-06) to the UniProt/Swissprot database. It makes sense that mites feeding in a suboptimal host will show differences in digestive tract development and this might be mediated by transcriptional regulation.

Cluster 2 and 3 CDEG up-regulated in A. mellifera

We found 208 CDEG up-regulated in A. mellifera in cluster 2. However, only eight out of these 208 genes had an associated GO term. The top 10 enriched GO terms associated with these genes are primarily involved in either oxidative metabolism and stress (mitochondrial respiratory chain complex, oxidoreductase complex) or in development and reproduction (developmental process involved in reproduction, germ cell development, establishment of endothelial barrier, cis-Golgi network, post-embryonic organ development, cellular process involved in reproduction; Table 6). For a full report see Additional file 7: Table S7. Only 80 out of the 208 genes had a significant Blastx similarity hits (E-value ≤ 1e-06) to the M. occidentalis predicted peptides (Additional file 6: Table S8) and only 88 out the 208 genes had significant Blastx similarity hits (E-value ≤ 1e-06) to the UniProt/Swissprot database. We found 56 CDEG up-regulated in A. mellifera contained in cluster 3. However, only two out of these 56 genes had a GO term associated with them. Visual inspection of the GO terms associated with these genes are related to either apoptosis (Bcl-2 family protein complex and B cell apoptotic process, BH-domain binding), or the following terms: epoxide hydrolase activity, leukotriene metabolic process, ether hydrolase activity and Type I pneumocyte differentiation (Table 6). For a full report see Additional file 8: Table S9. Furthermore, only 15 out of the 56 genes had a significant Blastx similarity hits (E-value ≤ 1e-06) to the M. occidentalis predicted peptides (Additional file 6: Table S10) and only 12 out the 56 genes had significant Blastx similarity hits (E-value ≤ 1e-06) to the UniProt/Swissprot database.

Discussion

In this study we look at the relative expression of mite genes with respect to the host on which they were found reproducing. Because, there is no external standard, is it impossible to estimate absolute expression levels. For brevity, we refer to genes that have lower relative expression in mites reproducing on A. mellifera compared to mites reproducing in A. cerana, as down-regulated.

Functions of consistently differentially expressed genes

An analysis of the functions of the consistently differentially expressed mite genes (CDEG) that were differentially expressed (DE) between V. jacbosoni mites that differed in their ability to parasitize European honey bees revealed several trends. Only 23 transcripts were down-regulated in mites reproducing on A. mellifera. These included genes coding Proteins with RNAII polymerase promoter-region specific DNA-binding activity, as well as genes involved in digestive tract development. These results suggest that some transcription factors are down-regulated on this host and are possibly involved in the host-parasite interaction. Genes involved in digestive tract development are also interesting because feeding on the host may influence their expression. However, the obvious and surprising trend overall is that 91% of the DE transcripts were more highly expressed in mites using A. mellifera as a host.

The two largest classes of genes that were more highly expressed in mites growing on A. mellifera hosts contained nuclear encoded mitochondrial genes and genes involved in metabolic regulation and apoptosis. The overall Up-regulation of genes involved in some primary metabolism as described above may be a result of stress induced in the mites. These results suggest that these mites may have been exposed to more stress than they would have been on the optimal host A. cerana. Included in this broad category were genes encoding 8 mitochondrial proteins, a heatshock protein and a conserved NAD+ sensing histone deacetylase,SIRT6, that regulates glucose homeostasis in mammals [41]. Other CDEG that have roles in cellular primary metabolism were observed including 6-phosphofructokinase, a coordinator of glucose metabolism and cell cycle, phospholipase A2 activating protein, involved in calcium/CaMKII signaling, and a phosphodiesterase 8A homolog, a regulator of cyclic AMP levels [42–44]. Up-regulation of genes involved in primary metabolism may be a result of stress induced in the mites living on an atypical host. However, V. jacobsoni reproduction is not restricted to drone brood on A. mellifera, but is also found reproducing in the worker brood, which might indicate that this mite is rapidly adapting to live and reproduce in their new host.

Stress induced by a number of treatments in Drosophila results in increased expression of mitochondrial and heat shock genes [45]. Interestingly, genes putatively involved in reproductive development and growth were also more highly expressed in mites reproducing on A. mellifera. For example, a transcript with highly significant alignment to Drosophila Src64 was over expressed. This gene encodes a tyrosine kinase that is required for Drosophila oogenesis, and affects insulin signaling through interactions with the transcription factor dFOXO [46, 47].

Our samples come from populations that differ in their ability to reproduce on A. mellifera, but not only were they exposed to different host colony environments, they were also geographically separated, perhaps confounding our differential expression analyses. However, other analyses indicate that our samples of mites parasitizing A. mellifera are likely derived from the same source population as the mites we collected parasitizing A. cerana [25], and colony environments are buffered from external climactic conditions. These differential expression analyses provide a valuable resource for future studies into the mechanisms involved in this singular host shift to European honey bees. Discovering why mated mites fail to lay eggs upon entering brood cells of different honey bee host species is critical to our understanding of this devastating pest species, and for predicting the ability of Varroa mites to successfully make a host switch to A. mellifera.

Conclusions

Some genes are differentially expressed in the mites reproducing on A. mellifera and A. cerana, with more variation in gene expression among mites that reproduce on A. mellifera. A small set of genes showed reduced expression in mites on the A. mellifera host, including putative transcription factors and digestive tract developmental genes. The vast majority of differentially expressed genes were up-regulated in this host. This gene set showed enrichment for genes associated with mitochondrial respiratory function and apoptosis, suggesting that mites on this host may be experiencing higher stress, and may be less optimally adapted to parasitize it. The restricted ability of V. jacobsoni mites to successfully reproduce on the A. mellifera host, to which they are incompletely adapted, may be related to this stress. Some genes involved in reproduction and oogenesis were also differentially expressed, which should be further studied in regard to this host shift.

Abbreviations

- CPM:

-

Counts per million

- EC:

-

Expected counts

- FPKM:

-

Fragments per kilobase per million reads

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- RNA-Seq:

-

RNA sequencing

References

Ghazoul J. Buzziness as usual? Questioning the global pollination crisis. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20(7):367–73.

Aizen MA, Harder LD. The global stock of domesticated honey bees is growing slower than agricultural demand for pollination. Current Biol. 2009;19(11):915.

Klein AM, Vaissière BE, Cane JH, Steffan-Dewenter I, Cunningham SA, Kremen C, Tscharntke T. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;274(1608):303–13.

Williams GR, Tarpy DR, Vanengelsdorp D, Chauzat MP, Cox-Foster DL, Delaplane KS, Neumann P, Pettis JS, Rogers REL, Shutler D. Colony Collapse Disorder in context. Bioessays. 2010;32(10):845–6.

van Engelsdorp D, Evans JD, Saegerman C, Mullin C, Haubruge E, Nguyen BK, Frazier M, Frazier J, Cox-Foster D, Chen YP, et al. Colony collapse disorder: a descriptive study. PloS One. 2009;4(8):e6481.

Oldroyd BP. What’s killing American honey bees? PLoS Biol. 2007;5(6):e168.

van Engelsdorp D, Hayes J, Underwood RM, Pettis J. A sof honey bee colony losses in the US, Fall 2007 to Spring 2008. PloS One. 2008;3(12):e4071.

Currie RW, Pernal SF, Guzmán-Novoa E. Honey bee colony losses in Canada. J Apic Res. 2010;49(1):104–6.

Dahle B. The role of Varroa destructor for honey bee colony losses in Norway. J Apic Res. 2010;49(1):124–5.

Guzmán-Novoa E, Eccles L, Calvete Y, McGowan J, Kelly PG, Correa-Benítez A. Varroa destructor is the main culprit for the death and reduced populations of overwintered honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Ontario, Canada. Apidologie. 2010;41(4):443–50.

Shimanuki H, Knox DA. Parasitic mite syndrome: the symptoms. Am Bee J. 1994;134:827–8.

Bowen-Walker PL, Martin SJ, Gunn A. The transmission of deformed wing virus between honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) by the ectoparasitic mite varroa jacobsoni Oud. J Invertebr Pathol. 1999;73(1):101–6.

Rosenkranz P, Aumeier P, Ziegelmann B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;103 Suppl 1:S96–S119.

Bailey L. Honey bee pathology. London; New York: Academic; 1981.

Martin SJ. The role of Varroa and viral pathogens in the collapse of honeybee colonies: a modelling approach. J Appl Ecol. 2001;38(5):1082–93.

Dainat B, Evans JD, Chen YP, Gauthier L, Neumann P. Dead or alive: deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor reduce the life span of winter honeybees. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(4):981–7.

Oldroyd BP. Coevolution while you wait: Varroa jacobsoni, a new parasite of western honeybees. Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;14(8):312–5.

Solignac M, Cornuet JM, Vautrin D, Le Conte Y, Anderson D, Evans J, Cros-Arteil S, Navajas M. The invasive Korea and Japan types of Varroa destructor, ectoparasitic mites of the Western honeybee (Apis mellifera), are two partly isolated clones. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2005;272(1561):411–9.

Navajas M, Anderson DL, de Guzman LI, Huang ZY, Clement J, Zhou T, Le Conte Y. New Asian types of Varroa destructor: a potential new threat for world apiculture. Apidologie. 2010;41(2):181–93.

Navajas M. Tracking the colonisation history of the invasive species Varroa destructor. In: Sabelis MW, Bruin J, editors. Trends in Acarology. Netherlands: Springer; 2010. p. 375–8.

Biasiolo A. Lack of allozyme variability amongVarroa mite populations. Exp Appl Acarol. 1992;16(4):287–94.

Anderson DL, Trueman JW. Varroa jacobsoni (Acari: Varroidae) is more than one species. Exp Appl Acarol. 2000;24(3):165–89.

Kraus B, Hunt G. Differentiation of Varroa jacobsoni Oud populations by random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Apidologie. 1995;26(4):283–90.

Anderson DL. Non- reproduction of Varroa jacobsoni in Apis mellifera colonies in Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. Apidologie. 1994;25(4):412–21.

Roberts J, Anderson D, Tay W. Multiple host shifts by the emerging honeybee parasite, Varroa jacobsoni. Mol Ecol. 2015;24(10):2379–91.

Schmieder R, Edwards R. Fast identification and removal of sequence contamination from genomic and metagenomic datasets. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17288.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20.

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–52.

Haas BJ, Delcher AL, Mount SM, Wortman JR, Smith RK, Hannick LI, Maiti R, Ronning CM, Rusch DB, Town CD, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(19):5654–66.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9.

Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(9):1061–7.

Garber M, Grabherr MG, Guttman M, Trapnell C. Computational methods for transcriptome annotation and quantification using RNA-seq. Nat Methods. 2011;8(6):469–77.

Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323.

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550.

Leng N, Dawson JA, Thomson JA, Ruotti V, Rissman AI, Smits BMG, Haag JD, Gould MN, Stewart RM, Kendziorski C. EBSeq: an empirical Bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(8):1035–43.

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40.

Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Williams TD, Nagaraj SH, Nueda MJ, Robles M, Talon M, Dopazo J, Conesa A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(10):3420–35.

Wang X-W, Luan J-B, Li J-M, Bao Y-Y, Zhang C-X, Liu S-S. De novo characterization of a whitefly transcriptome and analysis of its gene expression during development. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1):1–11.

Xia Z, Xu H, Zhai J, Li D, Luo H, He C, Huang X. RNA-Seq analysis and de novo transcriptome assembly of Hevea brasiliensis. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;77(3):299–308.

Hoy M, Yu F, Meyer J, Tarazona O, Jeyaprakash A, Wu K. Transcriptome sequencing and annotation of the predatory mite Metaseiulus occidentalis (Acari: Phytoseiidae): a cautionary tale about possible contamination by prey sequences. Exp Appl Acarol. 2013;59(3):283–96.

Zhong L, Urso A, Toiber D, Sebastian C, Henry RE, Vadysirisack DD, Guimaraes A, Marinelli B, Wikstrom JD, Nir T, et al. The Histone Deacetylase Sirt6 Regulates Glucose Homeostasis via Hif1α. Cell. 2010;140(2):280–93.

Yalcin A, Clem BF, Imbert-Fernandez Y, Ozcan SC, Peker S, Neal J, Klarer AC, Clem AL, Telang T, Chesney J. 6- Phosphofructo- 2- kinase (PFKFB3) promotes cell cycle progression and suppresses apoptosis via Cdk1- mediated phosphorylation of p27. Cell Death and Dis. 2014;5(7):e1337.

Doroudi M, Plaisance MC, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Membrane actions of 1α, 25(OH) 2D3 are mediated by Ca2+/ calmodulin- dependent protein kinase II in bone and cartilage cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;145:65–74.

Conti M, Mika D, Richter W. Cyclic AMP compartments and signaling specificity: Role of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. J Gen Physiol. 2014;143(1):29–38.

Brown JB, Boley N, Eisman R, May GE, Stoiber MH, Duff MO, Booth BW, Wen J, Park S, Suzuki AM, et al. Diversity and dynamics of the Drosophila transcriptome. Nature. 2014;512(7515):393–9.

Bulow MH, Bulow TR, Hoch M, Pankratz MJ, Junger MA. Src tyrosine kinase signaling antagonizes nuclear localization of FOXO and inhibits its transcription factor activity. Scintific Reports. 2014;4:4048. doi:10.1038/srep04048.

Djagaeva I, Doronkin S, Beckendorf SK. Src64 is involved in fusome development and karyosome formation during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev Biol. 2005;284(1):143–56.

Acknowledgements

The financial support for this study and an ongoing full genome sequencing project was provided by USDA-ARS and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (grant 2009-05254). We thank Catherine Hill and Jeff Stuart for helpful manuscript comments. We thank Rick Westerman and Phillip San Miguel for their advice in regards to libraries preparation and preliminary analysis of the sequence data. We also thank Ann Christine Catlin for helping to create the database, were the raw reads data and assemblies of this mite has been deposited.

Availability of data and materials

All data for this project regarding sample collection, RNA sequences (raw reads), newly discovered transcripts assemblies have been deposited at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the BioProject: PRJNA321056, SRA: SRP075576, BioSamples: SAMN04992106, SAMN04992107, SAMN04992108, SAMN04992109, SAMN04992110, SAMN04992111, SAMN04992112, SAMN04992113, SAMN04992114. Transcriptome Shotgun Assemblies, have been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank (de novo transcriptome accession: GETM00000000, genome guided assembly accession: GETO00000000 and trinity/PASA hybrid transcriptome accession: GETP00000000). Other data sets supporting the results of this article are included in the additional files section described in this paper.

In addition, since December 18, 2015 all dataset for this project has been publicly available at the Purdue DataCenterHub repository (https://datacenterhub.org/). This database contains a resource page (https://datacenterhub.org/resources/382) that describes the research project and the dataset sequenced and assembled (transcriptome assemblies described in this database are the assemblies before deposited at NCBI). Exploration of this database is supported by a “dataviewer” that presents the data as a spreadsheet with each row containing information for one sample. This database name is: RNA sequences and assemblies of Varroa jacobsoni (honey bees varroa mites), with a DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4231/H4159K and has been also linked to the BioProject Accession: PRJNA321056.

Authors’ contributions

GA Conceived the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; DA Collected and provided the samples for this study; MG assisted in data analysis and interpretation. GH conceived the experiments and assisted in data analysis. MG, GH and JE assisted in drafting the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Distribution of normalized FPKM. Histograms of the normalized FPKM values in the different samples showing the distribution of these values about the median. (PDF 211 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Varroa jacobsoni, 1013 differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05 and absolute logFC ≥ 2) using EdgeR. (XLSX 145 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Varroa jacobsoni, 586 differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05) using DESeq2. Table S3. Varroa jacobsoni, 6908 differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05) using EBSeq. (XLSX 604 kb)

Additional file 4: Tables S4.

Selected target genes (37,661) used as a reference set for Fisher’s exact test. (XLSX 2572 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S5.

GO terms significantly over-represented in mite genes that are down-regulated in the A. mellifera host, cluster 1 (23 genes). (XLS 43 kb)

Additional file 6: Table S6.

Genes that had a significant Blastx similarity hit (e-value ≤ 1e-06) to the M. occidentalis predicted peptideds (cluster 1). Table S8. Genes that had a significant Blastx similarity hit (e-value ≤ 1e-06) to the M. occidentalis predicted peptideds (cluster 2). Table S10. Genes that had a significant Blastx similarity hit (e-value ≤ 1e-06) to the M. occidentalis predicted peptideds (cluster 3). (XLSX 45 kb)

Additional file 7: Table S7.

GO terms significantly over-represented in mite genes that are down-regulated in the A. mellifera host, cluster 2 (208 genes). (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 8: Table S9.

GO terms significantly over-represented in mite genes that are down-regulated in the A. mellifera host, cluster 3 (56 genes). (XLS 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Andino, G.K., Gribskov, M., Anderson, D.L. et al. Differential gene expression in Varroa jacobsoni mites following a host shift to European honey bees (Apis mellifera). BMC Genomics 17, 926 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3130-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3130-3