Abstract

Background

A range of higher animal taxa are shared across various chemosynthesis-based ecosystems (CBEs), which demonstrates the evolutionary link between these habitats, but on a global scale the number of species inhabiting multiple CBEs is low. The factors shaping the distributions and habitat specificity of animals within CBEs are poorly understood, but geographic proximity of habitats, depth and substratum have been suggested as important. Biogeographic studies have indicated that intermediate habitats such as sedimented vents play an important part in the diversification of taxa within CBEs, but this has not been assessed in a phylogenetic framework. Ampharetid annelids are one of the most commonly encountered animal groups in CBEs, making them a good model taxon to study the evolution of habitat use in heterotrophic animals. Here we present a review of the habitat use of ampharetid species in CBEs, and a multi-gene phylogeny of Ampharetidae, with increased taxon sampling compared to previous studies.

Results

The review of microhabitats showed that many ampharetid species have a wide niche in terms of temperature and substratum. Depth may be limiting some species to a certain habitat, and trophic ecology and/or competition are identified as other potentially relevant factors. The phylogeny revealed that ampharetids have adapted into CBEs at least four times independently, with subsequent diversification, and shifts between ecosystems have happened in each of these clades. Evolutionary transitions are found to occur both from seep to vent and vent to seep, and the results indicate a role of sedimented vents in the transition between bare-rock vents and seeps.

Conclusion

The high number of ampharetid species recently described from CBEs, and the putative new species included in the present phylogeny, indicates that there is considerable diversity still to be discovered. This study provides a molecular framework for future studies to build upon and identifies some ecological and evolutionary hypotheses to be tested as new data is produced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the deep-sea, there is no sunlight to fuel photosynthetic primary production. Energy to sustain life is therefore either derived from organic matter falling from surface waters, or from chemosynthetic primary production. Chemosynthetic bacteria and archaea, which utilize energy from reduced chemical compounds (e.g. hydrogen sulfide or methane) instead of sunlight, are found both free-living and as symbionts of macrofauna [1]. Compared to the surrounding food-limited deep-sea, chemosynthesis-based ecosystems (CBEs) are teeming with macrofauna, and specialized organisms can reach extremely high population densities (e.g. [2]).

Three main categories of deep-sea CBEs are defined based on the process that forms the reduced chemical compounds: hydrothermal vents, cold seeps and organic falls [3]. However, there are some habitats that have been considered intermediates between vents and seeps, such as sedimented vents [4] and hydrothermal seeps [5], and recent work has suggested that CBEs form a continuum of environmental conditions [5,6,7]. Some animal clades are shared across vents, seeps and falls, which demonstrates the evolutionary link between these habitats [8], but on a global scale the number of shared species is low [3, 4, 9]. In addition to the geochemical differences between CBEs, the distinctiveness of the fauna is affected by the geographic proximity of habitats [6, 10], and differences in depth [10, 11] and substratum [6, 7]. In the Guaymas Basin, where sedimented vents and seeps are found in close geographic proximity and at similar depth, the macrofaunal community composition is not determined by the type of ecosystem, but rather by environmental parameters that vary across ecosystems [6]. Similarly, no clear distinction was found between sedimented vents in Okinawa Trough and seeps at similar depths in Sagami Bay [10]. Recently, a biogeographic analysis demonstrated the importance of sedimented vents in linking vent and seep faunas on a global scale, and also indicated that sedimented vents might have been central in the evolution of taxa within CBEs [7].

Over the last decades, a number of phylogenetic studies have elucidated the evolutionary histories of fauna from CBEs, but these have mostly focused on the dominant symbiotrophic taxa such as vesicomyid and bathymodiolin bivalves [12,13,14,15,16] and siboglinid annelids [17,18,19]. The hypothesis that vent and seep mussels (Bathymodiolinae) evolved from wood-dwelling ancestors [20] has been followed by studies on other taxa, with either organic falls or seeps functioning as stepping-stones into the vent habitat [14, 15, 18, 21, 22]. However, the role of sedimented vents as an evolutionary stepping-stone has not previously been assessed in a phylogenetic framework.

Ampharetidae is a commonly occurring taxon at hydrothermal vents [23,24,25,26], cold seeps [2, 24, 26] and organic falls [27, 28] and can be a dominant part of the macrofaunal community [2, 4]. There are several species described from sedimented vents and one species is also recorded from the Costa Rica hydrothermal seep [23,24,25]. Although some species of ampharetids encountered in CBEs are also found in the surrounding deep-sea [29], many species are exclusively known from CBEs and are considered to be specialists [23,24,25,26,27]. Ampharetids are deposit feeders, and gut content, fatty acid and isotope analyses indicate that specialized ampharetids in CBEs are feeding on chemosynthetic bacteria [2, 30,31,32]. Most ampharetids are habitat-specific, and even when hydrothermal vents and cold seeps are found in close geographic proximity, the same species of ampharetids are usually not found in both habitats [25]. The almost ubiquitous presence of ampharetids in various CBEs makes them a good model taxon to study the evolution of habitat-use in heterotrophic animals.

Although Ampharetidae is one of the most common groups within CBEs, only two molecular phylogenies have been published to date, both with a limited taxon sampling of the family [23, 25]. The first study by Stiller et al. [25] focused on the genus Amphisamytha, which has 7 recognized species from vent and seep habitats. The second phylogeny by Kongsrud et al. [23] included five additional species from CBEs belonging to the genera Pavelius, Paramytha and Grassleia and indicated that adaptation into CBEs has happened multiple times independently in Ampharetidae, but still with limited taxon sampling of non-CBE ampharetids. In this paper, we expanded upon previous efforts and present a multi-gene phylogeny with increased taxon sampling of species both from CBEs and other habitats. In addition, we performed a review of the habitat-use of CBE-specialized ampharetids. With this we aimed to: 1) assess the effect of environmental factors such as substratum, temperature and depth on the habitat-specificity and distributions of ampharetids in CBEs; 2) test the hypothesis of multiple evolutionary origins of ampharetids in CBEs; and 3) infer the frequency and direction of habitat-shifts in the evolutionary history of Ampharetidae, with special attention paid to the role of intermediate habitats such as sedimented vents and hydrothermal seeps.

Methods

Review of habitat use

For the review we only included species of Ampharetidae obligate to CBEs. Although molecular data indicates that Alvinellidae should be considered a subfamily of Ampharetidae ([25], present study), species in this group were not included in the review due to their unique and very specialized ecology [33]. Because of the difficulty in validating records of species that are not formally described (recorded as genus sp. nov.), we further limited the review to species that are formally described, plus the undescribed species included in the present phylogeny (23 species in total). Details of the habitat where the specimens were collected are often not included in published papers, therefore cruise reports were also studied when these were available [34]. For each record, we collected data on: habitat (hydrothermal vent, sedimented vent, inactive vent, hydrothermal seep, cold seep or organic fall), temperature, water/fluid chemistry, depth, substratum and geographical locality. All literature included in the review can be found in Additional file 1.

Molecular work

Taxon sampling

The focus of this paper is on species of Ampharetidae from CBEs, but we also included a broad taxonomic sampling of Ampharetidae from non-CB habitats. In total 101 specimens of Ampharetidae were included in the molecular dataset, of which 38 specimens were from CBEs. Twenty-one ampharetid genera (including both subfamily Ampharetinae and Melinninae) were represented in the dataset, which comprises approximately one third of the currently recognized genera in Ampharetidae [35] (see Additional file 2 for specimen list with metadata). Four hitherto undescribed species of Ampharetidae from CBEs were included; Anobothrus sp. A from the Snake Pit vent field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Anobothrus sp. B and Pavelius sp. B from methane seeps on the Hikurangi Margin off New Zealand [2] and Pavelius sp. A from mud volcanoes in the Gulf of Cadiz off Portugal [36]. As outgroup, we chose Pista cristata (Terebellidae) and we also included representatives of ‘Alvinellidae’ (Paralvinella spp.). DNA voucher specimens are deposited at the Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen (ZMBN), the Scripps Oceanography Benthic Invertebrate Collection (SIO-BIC) or the German Center for Marine Biodiversity Research, Senckenberg (DZMB).

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

Four genetic markers were selected for this study, the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) and 16S ribosomal DNA (16S), and the nuclear 18S and 28S ribosomal DNA (18S and 28S). Tissue for DNA extraction was, when possible, taken from branchiae or the posterior part of the worm, but in some cases the animals were so small that it was necessary to use the whole animal. In these cases, additional specimens from the same sample act as DNA-vouchers. Most of the molecular work was performed at the Biodiversity Laboratories, University of Bergen, except amplification and sequencing of 28S from Amphisamytha spp., which was done at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. DNA extraction and amplification of COI, 16S and 18S was performed as described in [23]. Partial sequences of 28S were obtained using the primers Po28R4 (5′-3′ GTTCACCATCTTTGGGGTCCCAAC, [37]) and 28F5 (5′-3′ CAAGTACCGTGAGGGAAAGTTG, [38]). For Amphisamytha spp. the PCR reactions consisted of 12.5 μl (μl) Conquest PCR Master Mix, 1 μl of each of the primers, 50–100 ng DNA and ddH2O to make the final reaction volume 25 μl. For the remaining specimens, the PCR reactions were set up as in [23]. The PCR cycling profile for 28S for all specimens was as follows: 3 min at 94 °C, 7 cycles with 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C and 2 min at 72 °C, 35 cycles with 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 52 °C, and 2 min at 72 °C, and finally 10 min at 72 °C. Quality and quantity of PCR products was assessed by gel electrophoresis imaging using a FastRuler DNA Ladder (Life Technologies) and GeneSnap and GeneTools (SynGene) for image capture and band quantification. In cases where the standard PCR protocol did not yield satisfying product a new PCR was performed with 1 μl dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) added. If gel electrophoresis showed multiple bands, the total PCR product was run on a new gel and the desired band was extracted from the gel using MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR products of Amphisamytha spp. were cleaned using ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA) and sequenced by Retrogen Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), while for the remaining specimens purification and sequencing was performed as in [23].

Phylogenetic analyses

Forward and reverse sequences were assembled in Geneious (Biomatters Ltd.), checked for contamination using BLAST [39] and have been deposited in GenBank (see Additional file 2 for accession numbers). Additional sequences of Ampharetidae were downloaded from GenBank and included in the analyses (see Additional file 2). Three sets of alignments were made, one with the complete dataset, and two with subsets of taxa corresponding to clades identified in initial analyses (Clade A and Clade C, see Results) and with Melinna cristata as outgroup. The alignments of Clade A and C were made to reduce the proportion of ambiguously aligned regions, allowing a higher number of positions to be included, and also to save computation time for species tree reconstruction with STACEY (see below).

COI sequences were aligned in Geneious using MUSCLE [40], and 16S, 18S and 28S sequences were aligned using the MAFFT online server [41] and the option for automatic selection of alignment algorithm [42, 43]. The alignments were inspected and minor corrections were made manually in Geneious. Blocks of ambiguous data were identified and excluded from the 16S, 18S and 28S alignments using the Gblocks online server [44] with relaxed settings [45, 46]. Substitution saturation for the first, second and third codon position of COI was assessed in DAMBE6 [47] using the Xia method [48, 49]. The third codon position showed strong signs of saturations in all alignments, so this position was excluded in the following analyses. Concatenated matrices of all genes were generated using Sequence Matrix [50] with missing data coded as question marks (?). The best partition scheme and the best fitting model of evolution for each partition for the combined analyses were found using Partition Finder v2.1.1 with the greedy algorithm and PhyML ([51,52,53] see Additional file 3 for models). The I + G model for rate heterogeneity was suggested for some partitions, but due to statistical concerns regarding the co-estimation of the alpha and invariant-site parameters (discussed in the RAxML manual [54]) we chose to use only the + G model instead for all analyses. The best partition scheme was found to be five partitions with each gene and the first and second codon position of COI as separate partitions.

Single genes and a concatenated matrix of all genes for the complete dataset were analysed by maximum likelihood using RAxML v8.1.22 [55] implemented in raxmlGUI v1.3.1 [56], and by Bayesian inference in MrBayes v3.2.2 [57]. For the single-gene datasets identical sequences were removed prior to analysis. All maximum likelihood analyses were done under the GTRGAMMA model with 200 thorough bootstrap analyses for single gene analyses and 1000 for the concatenated dataset. In the MrBayes analyses partitions and substitution models were defined as suggested by Partition Finder, but since the TIM, TVM and TRN substitution models are not available in MrBayes these were replaced by the GTR model. Three parallel runs were performed for each MrBayes analysis with 5 million generations for single gene analyses and 10 million for concatenated analyses. MrBayes analyses were run on the Lifeportal server at the University of Oslo [58].

Due to computational constraints, we performed species tree analysis for Clade A and Clade C separately under the multi-species coalescent model (MSC) using STACEY v1.2.2 [59, 60] in BEAST2 v 2.4.4 [61]. STACEY implements species delimitation and species tree estimation within the same MCMC run, and therefore does not require any a priori species assignments [60]. All specimens were defined as separate species (leaving delimitation to the analysis), and the outgroup was set by defining the ingroup as monophyletic. Site and clock models were unlinked for all partitions, while the tree model was linked for all the mitochondrial partitions, and unlinked for the other partitions. Initially, analyses were run with substitution models as suggested by Partition Finder, but these analyses would not reach convergence, so the model was simplified by setting all site models as HKY + G. Gamma category count was set to 4 and gamma shape was estimated. Ploidy was set to 1 for the mitochondrial markers and 2 for the nuclear markers. The uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock was selected as clock model for all partitions and the prior for clock rate was set as a lognormal distribution with M = 0 and S = 1. The relative death rate was fixed to 0.5, the prior for the species growth rate was given a lognormal distribution with a mean (M) of 4.6 and standard deviation (S) of 2, and popPriorScale was modeled with a lognormal distribution with M = −7 and S = 2. The remaining priors were left at the default. Six independent analyses were run for clade A and two for clade C with 1 × 108 generations and sampling every 10,000 generations. BEAST2 analyses were run on the CIPRES Science Gateway [62]. The log files were examined in Tracer v1.5 to check for convergence (ESS > 200 for all parameters of the combined analyses [63]). Analyses were combined and burn-in (10% for each analysis) was removed using LogCombiner v2.4.4 and maximum clade credibility trees were generated in TreeAnnotator v2.4.4. Both of these programs are part of the BEAST2 package [61]. All trees were converted to graphics using FigTree v1.4.0 [64] and final adjustments were made in Adobe Illustrator v16.0.4 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). Similarity matrices from the species delimitation analyses were calculated using the software SpeciesDelimitationAnalyser [65] and an R-script created by Graham Jones included in the supplementary information for DISSECT [66]. Heatmaps were generated using the R package pheatmap [67].

To generate species trees for Clade A and C with each tip representing a species, new analyses were run in STACEY with species defined according to the species delimitation results from the first analyses, i.e. all clusters with pp. > 0.8 were designated as separate species. All the other settings and priors were the same as in the first analyses, the results were combined, and consensus trees generated as described above. Ancestral states were reconstructed using parsimony in Mesquite v 3.11 [68].

Results

Distributions and habitat use

All the compiled data on habitat use with references and taxonomic authorities can be found in Additional file 1. In total, 24 species of Ampharetidae, representing eight genera, are known exclusively from CBEs, including the four putative new species included in the phylogeny presented herein, but excluding Alvinellidae (Table 1). Eclysippe yonaguniensis was originally described from a station with “low CO2 seepage” [24], but this was in fact a reference station unaffected by CO2 (M. Reuscher pers. comm.). Eclysippe yonaguniensis is therefore not considered as obligate to CBEs and consequently excluded from this review. Amage benhami is recorded from cold seeps on Hydrate Ridge (Cascadia Margin, NE Pacific) and from the Ross Sea (Antarctic) [26, 69], but it is unclear if the latter locality could have been a cold seep. There are indications that there are cold seeps in the Ross Sea [70], and for the purpose of this review we considered A. benhami a seep-specialist. Grassleia sp. A from the Guaymas Basin ([23], this study), is similar to Grassleia hydrothermalis, but there are some subtle morphological differences from the original description. Due to these differences, and the geographical distance to the type locality of G. hydrothermalis, we decided to designate these specimens as a separate species, but this needs to be reassessed when sequence data of G. hydrothermalis from the type locality becomes available.

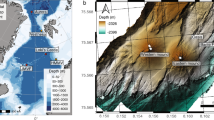

Ampharetids are recorded from CBEs in all world oceans (Fig. 1), but the highest diversity is described from the Pacific Ocean, with eight species in the East-Pacific and six species in the West-Pacific (Table 1). The Atlantic Ocean has six described species, two species are known from the Arctic and the Southern and Indian Oceans has one species each. Most seep-dwelling ampharetids are recorded from the Pacific, while ampharetids from organic falls are hitherto only described from the North Atlantic. There is often more than one species of ampharetids recorded from the same locality, and the area with the highest number of co-occurring ampharetids is the seeps on Hydrate Ridge (Cascadia Margin, NE Pacific), where four species are recorded (Table 1).

Map of all sampling localities of the ampharetids included in the review. Habitats are coded as follows: Blue circle = cold seep, red circle = sedimented vent/hydrothermal seep, red triangle = hydrothermal vent, blue triangle = inactive vent, blue square = organic fall. Very closely spaced localities were dislocated slightly for clarity

Nine species are known from hydrothermal vents only (six from bare-rock vents and three from sedimented vents), seven species from cold seeps only, three species from organic falls (one from decaying bones and two from decaying wood) and four species from mixed habitats (Table 1). The four species recorded from mixed habitats are: Amphisamytha fauchaldi, Amphisamytha vanuatuensis, Anobothrus apaleatus and Grassleia hydrothermalis. Amphisamytha fauchaldi has been recorded from cold seeps, a hydrothermal seep and sedimented hydrothermal vents, and is thus exclusively found in sedimented habitats [25]. Grassleia hydrothermalis was originally described from Escanaba Trough, which has hydrothermal venting both in hard-surface and sedimented settings [71]. It is, however, unclear which habitat G. hydrothermalis was collected from, because the original description states that it was collected from sediments “where hydrothermal fluid percolates to the surface” [72], but in another paper describing the same sampling cruise it is recorded as collected from vestimentifera washings from a hard-surface habitat [71]. For the purpose of this paper we will follow the original description and consider the type locality to be sedimented vents. Grassleia hydrothermalis has also been recorded from cold seeps on Hydrate Ridge [73]. Amphisamytha vanuatuensis was described from a cold seep on Edison Seamount in the West-Pacific, and at nearby hydrothermal vents [26]. High levels of H2S have been detected on Edison Seamount, but no temperature anomaly, and it is therefore classified as a cold seep [74, 75]. Anobothrus apaleatus was described from cold seeps on Hydrate Ridge, but also from an inactive vent on the Southern East Pacific Rise [26].

Six species (Grassleia hydrothermalis, Amphisamytha lutzi, Amphisamytha fauchaldi, Anobothrus apaleatus, Decemunciger apalea and Amphisamytha vanuatuensis) occupy depth ranges of over 1500 m, but the remaining species have a very limited recorded depth-distribution (< 500 m). There is a clear connection between depth range and habitat specificity, with the four species recorded from mixed habitats being among the six species with the widest depth ranges (Table 1). Amphisamytha lutzi, however, is an outlier among the vent specific species with a very wide depth range (around 2500 m; Table 1). Vent-specific species are generally found at deeper depths than seep-specific species, but the seep-dwelling Glyphanostomum holthei from the Aleutian Trench has a deepest recorded depth of nearly 5000 m. The species from organic falls have very variable depth distributions; Decemunciger apalea is distributed from 1830 to 3506 m, while Endecamera palea and Paramytha ossicola have only been recorded from 3995 m and 1000 m, respectively.

Although exact temperature data were not available for most species, the data reviewed show that ampharetids at hydrothermal vents usually occupy areas with low to medium temperatures (from ambient up to ~20 °C), and most species for which temperature data were available are found in a wide range of temperatures (Table 1). Amphisamytha vanuatuensis and Amphisamytha fauchaldi, which inhabit both vents and seeps, have a similar temperature range as the vent-specialist species (Table 1). The only species found at high temperatures is Amphisamytha carldarei, which is found together with Paralvinella sulfincola near high temperature venting (as Amphisamytha galapagensis [31]). Paralvinella sulfincola is always found in the warmest areas around the vent, and is known to tolerate temperatures well over 40 °C [76]. Amphisamytha carldarei is, however, most common in cooler areas occupied by Riftia pachyptila, and even quite abundant at old chimneys with reduced flow and dead tubeworms [31]. The ability to live in very low flow conditions is also demonstrated by Anobothrus apaleatus, which is described from an inactive vent on the Southern East-Pacific Rise [26].

Ampharetids in CBEs are found on a wide range of substrata, but for simplicity they were grouped into the five categories shown in Table 1. The most common substratum among all species is sediments (17 species), while 8 species are recorded on/among other animals (bivalves, tubeworms, crabs) and 6 species are recorded from hard substrata. Many species are recorded from multiple types of substrata, but this is most common with vent-specific species and species from mixed habitats. Species that are recorded as sitting on other animals do not appear to have a very close association to the “substratum species”, most of these are found on several different animals, and often on sediment and hard substrata as well. Most of the seep-specific species are only known from sediments (Pavelius spp., Grassleia sp. A and Anobothrus sp. B), but Glyphanostomum holthei is an exception, this species is also associated with clam beds (Vesicomyidae). Species from organic falls are either dwelling in the enriched sediments around the fall (Decemunciger apalea and Endecamera palea) or sitting on the fall itself (Paramytha ossicola).

Phylogenetic analyses

In total 321 sequences (from 51 putative species) were included in the phylogenetic analyses, of which 227 were newly generated for this study (Additional file 3).

Analyses of the concatenated complete dataset recovered Alvinellidae within the subfamily Ampharetinae, making this subfamily paraphyletic (Fig. 2). The positions of Samythella neglecta and Alvinellidae varied between the gene trees (Additional files 4, 5, 6, 7), and the position of Alvinellidae within Ampharetinae was unresolved in the resulting tree from the concatenated analysis. Samythella neglecta was recovered as sister to the rest of Ampharetinae + Alvinellidae in the tree from the concatenated analysis with high support (PP = 1, BS = 84, see Fig. 2). Apart from Samythella neglecta, the remaining species of Ampharetinae sensu stricto (excluding Alvinellidae) were recovered in three well-supported clades, which were also recovered in all gene-trees (Additional files 4, 5, 6, 7). A sister relationship between clade A and B received maximum support in the Bayesian analysis (PP = 1), but bootstrap support was low (BS = 69).

Consensus tree from the MrBayes analysis of the concatenated, complete dataset. Clades from CBEs are indicated with a grey box. Branch labels are showing posterior probabilities and bootstrap values (PP/BS). Support values lower than 0.75/50 are not shown. An asterisk (*) indicates PP = 1 and BS = 95–100, and a dash (−) indicates the node was not recovered in the best maximum likelihood tree. Tips are labelled following the morphological species delimitation, but specimens that were not clustered together with a posterior probability above 0.8 in the Stacey analysis were given distinct names (e.g. Ampharete sp. A and sp. B). Numbers in brackets indicate the number of specimens per species

Two of the ampharetin clades, clade A and C, contained species from CBEs (Fig. 2). The topology within clades A and C varied between the gene trees, and some nodes received poor support in the concatenated analysis. These clades were realigned separately with Melinna cristata as outgroup. The new alignments contained fewer gaps, and a smaller proportion of the alignments was removed by Gblocks, allowing a higher total number of positions to be included in the analyses (see Additional file 8 for alignment statistics).

Several of the morphologically delimited species in clade A and C were not supported as a single cluster by the species delimitation in STACEY when applying a threshold of 95% posterior probability (Additional files 9 and 10). However, with a lower threshold (80%) most of the morphological species were supported as single clusters, with two exceptions: Sosane wireni and Sosane sp. A were originally identified as the same species (Sosane wireni), but this was not supported by the analyses (PP = 0.11), and the same was the case for Ampharete sp. A and B (PP = 0.16). The specimens in these clusters with PP < 0.8 were then assigned as separate putative species and given distinct names (e.g. Ampharete sp. A and sp. B) in all figures.

The topologies recovered from the species tree analyses of clades A and C were largely the same as from the concatenated analyses, but with higher support (Figs. 3 and 4). In clade A the species from CBEs were recovered in three sub-clades; one clade consisting of two species in Anobothrus (Clade A1), one clade consisting of Pavelius and Grassleia (Clade A2, five species) and one clade corresponding to Paramytha (Clade A3, two species). It should also be noted that Ampharete and Sosane were recovered as polyphyletic, with the species Ampharete octocirrata and Sosane wahrbergi failing to form clades with their respective congeners (Fig. 3). In clade C, Amphisamytha was polyphyletic (Fig. 4). The deep-sea Amphisamytha species from CBEs (Clade C1 and C2) formed a well-supported clade with Amage spp. The shallow-water Amphisamytha bioculata was recovered outside the clade consisting of the remaining Amphisamytha species + Amage, but its exact position relative to that clade was unresolved (Fig. 4).

Species tree of Clade A, including Melinna cristata as outgroup. Tips were labelled following the species delimitation by Stacey, and specimens that were not clustered together with a posterior probability above 0.8 were given distinct names. Branch labels are showing posterior probabilities, and an asterisk (*) indicates PP = 1. Clades from CBEs are indicated with a grey box, and the habitats of each species from CBEs are shown with symbols. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of specimens per species

Species tree of Clade C, including Melinna cristata as outgroup. Tips were labelled following the species delimitation by Stacey, and specimens that were not clustered together with a posterior probability above 0.8 were given distinct names. Branch labels are showing posterior probabilities, and an asterisk (*) indicates PP = 1. Clades from CBEs are indicated with a grey box, and the habitats of each species from CBEs are shown with symbols. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of specimens per species

Ampharetids from CBEs fell into five clades, with multiple types of CBEs represented in each clade. There was a predominance of vent-specific species in clade C2 (four of five species) and of seep-specific species in clade A2 (four of five species). Ancestral state reconstruction in Clade A gave ambiguous results for the ancestor of Clade A1 and A2, but for Clade A2 the ancestor was recovered as seep-dwelling, with one transition to sedimented vents in Pavelius smileyi (Fig. 5). In Clade C it is unresolved whether the ancestor of the clade of deep-sea Amphisamytha + Amage was from vents or non-CBEs, and thus it is unclear if the transition to CBEs happened once (with a back-transition in Amage) or twice independently in this clade. The ancestor of clades C1 and C2 were recovered as vent dwelling, with a transition to vent and seep in Amphisamytha vanuatuensis and to sedimented vent, hydrothermal seep and cold seep in Amphisamytha fauchaldi (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Ampharetids are among the most commonly encountered taxa in CBEs, but their ecology and evolutionary history is poorly known. The present study provides a thorough review of their habitat-use and a phylogenetic reconstruction with the by far most comprehensive taxon sampling of the family to date. The review shows that ampharetid species can inhabit a wide range of environmental conditions, and no apparent differences in substratum use or temperature tolerance were identified that could explain their habitat specificity. The phylogeny demonstrates the need for a taxonomic revision of the family, both on the generic, sub-family and family level. Ancestral state reconstruction of habitats in two clades of Ampharetidae shows that CBEs have been colonized multiple times independently, confirming previous findings [23]. Transitions between habitats is common within Ampharetidae, and the phylogeny indicates a potential role of intermediate habitats such as sedimented vents in the transition between different CBEs.

Distributions, environment and habitat specificity of ampharetids in CBEs

The ability of ampharetids to occupy a wide variety of habitats was remarked upon by McHugh and Tunnicliffe [31] with reference to Amphisamytha galapagensis. Molecular phylogenetics has since showed that A. galapagensis was a cryptic species complex, and some of the widespread records of this species have been assigned to other species [25]. However, the present study shows that the impression of ampharetid species as being very adaptable still holds true. Despite this apparent lack of specialization, most ampharetid species are restricted to one type of CBE, which may indicate that they are limited by environmental factors other than temperature or substratum.

The community of free-living microbes that ampharetids feed on varies both within and between CBEs [77, 78], and therefore trophic specialization may affect the habitat specificity of ampharetid species. Trophic studies of grazing gastropods at hydrothermal vents have revealed that some species are specialized on a particular microbial food-source, while others are more generalistic [79]. At present the trophic ecology of ampharetids is poorly known, hindering inferences about the influence of trophic specialization on habitat selectivity. However, Amphisamytha aff. Fauchaldi, which inhabits both sedimented hydrothermal vents and cold seeps in the Guaymas Basin, has been shown to have clear shifts in isotopic values between habitats, indicating a flexible diet [77]. It is possible that this flexibility is one factor that allows A. fauchaldi to inhabit different CBEs.

Interactions with other species is another factor that may be important in shaping the geographic ranges and habitat specificity of ampharetids in CBEs. There are several cases of multiple species of ampharetids inhabiting the same localities, e.g. up to four species are found at Hydrate Ridge (Table 1). This means that ampharetids are probably affected by competition from confamilial species, which may lead to niche partitioning and trophic specialization [79, 80]. If several species of ampharetids are present in a given CBE it might be difficult for new species to establish, and this effect could be reinforced if the colonizing species is mainly adapted to a different habitat.

The fact that all the species inhabiting multiple habitats have wide depth-ranges,whereas species exclusive to a single CBE mostly have narrow depth-ranges indicates that depth limitation might be a relevant factor for habitat specificity. This also follows logically, since vents are usually located at deeper depths than seeps and falls. A putative example of depth limitation can be found in Amphisamytha carldarei, which is found on the vents on the Juan de Fuca Ridge (2200–2500 m). This species might be unable to colonize the much shallower seeps on Hydrate Ridge (500–800 m), even though these are located in close geographic proximity. Another example is found in the Nordic Seas, where the ampharetids Pavelius smileyi and Paramytha schanderi are found at the Lokis Castle sedimented vents (ca. 2350 m [23]), but not at the nearby Håkon Mosby mud volcano (ca. 1250 m [29]). Again, it is possible that depth difference is limiting colonization of the seep. However, while depth differences might be a barrier for some species, this explanation probably does not apply to all ampharetids. For example, it is unlikely that differences in depth is preventing A. galapagensis (depth range 2335–2725 m) from colonizing the hydrothermal seep at Jaco Scar off Costa Rica (ca. 1800 m) or the seeps and sedimented vents in the Guaymas Basin (ca. 1500–2000 m).

Habitat-use is likely the result of a complex interplay between biotic, abiotic and evolutionary factors/processes; depth might be a limiting factor for some species, while for others it might be trophic specialization, competition or an interaction between the two. Given the limitations of the available data, it is also likely that more ampharetid species will be found to occupy multiple habitats as CBEs are explored further. CBEs are poorly sampled in some geographical regions such as the Indian, Southern and Arctic Oceans (see Fig. 1). In addition, cold seeps and organic falls are still under sampled compared to hydrothermal vents, and there is a significant lag between the discovery of CBEs and publications of taxonomically assured species records and species descriptions, which further limits the available data. Ampharetids are also small and easily overlooked, and the absence of ampharetids on species lists from CBEs might be due to insufficient sampling. Continued taxonomic effort, including the use of molecular data, is needed to test the validity of species with wide geographic distributions and ecological niches.

Taxonomic implications of the phylogeny

The present phylogeny recovered Alvinellidae (represented by two species of Paralvinella) within Ampharetidae, supporting previous findings by Stiller et al. [25]. Alvinella and Paralvinella were originally described as belonging to a subfamily of Ampharetidae, Alvinellinae [81, 82], but they were subsequently erected as a separate family, Alvinellidae [83]. Our results suggest that Alvinellidae should be placed within Ampharetidae. However, in the present study Ampharetinae was recovered as paraphyletic with respect to Alvinellidae, and the position of Alvinellidae relative to clades A, B and C was unresolved (Fig. 2). More data and even denser taxon sampling is needed to revise the subfamilies of Ampharetidae.

The taxonomy of Ampharetidae is complex, with a high number of genera, of which many only include one or a few species [84]. Efforts have been made previously to reduce the number of genera, but there is disagreement on which morphological characters should be emphasized [84,85,86]. Our results show that Ampharete octocirrata (formerly Sabellides octocirrata [86]) does not form a clade with the remaining species of Ampharete, and Sosane wahrbergi (previously Mugga wahrbergi [86]) was not recovered together with the remaining species of Sosane. The two putative new species from cold seeps on the Hikurangi Margin (Anobothrus sp. B and Pavelius sp. B) were previously suggested to constitute two new genera [32], but the current phylogeny places them with Anobothrus and Pavelius respectively. These incongruences between morphology-based taxonomy and molecular phylogenetics illustrate the importance of including molecular data in the much-needed taxonomic revision of Ampharetidae.

Amphisamytha was also found to be non-monophyletic. Amphisamytha spp. from CBEs are more closely related to Amage (here represented by Amage auricula and Amage sculpta) than to the shallow-water species Amphisamytha bioculata. Amage auricula is the type species of Amage, which is a large genus with 24 recognized species [87]. Further study including a larger taxon-sampling of Amage is needed to resolve the relationship between this genus and Amphisamytha. Molecular data from the type species of Amphisamytha, A. japonica, will be critical to revise the genus, but this is unfortunately not available at present. However, it seems likely that the Amphisamytha species from CBEs should be placed in another genus.

The species delimitation results in this study showed more ‘splitting’ relative to morphological species delimitation when applying a 95% threshold for posterior probabilities. However, when lowered to an to an 80% threshold, all morphological species were supported except two, which had much lower support values. The low levels of support for many species could be due to population structure, which may be misinterpreted under the MSC as distinct species [88], or an effect of missing data. However, the two morphologically identified species (Sosane wireni and Ampharete sp. A + B) that were recovered with much lower levels of support (PP < 0.2), warrants further study to reveal potential cryptic diversity.

Evolutionary history of Ampharetidae in CBEs

The reconstruction of ancestral habitats indicates that adaptation into CBEs has happened at least four times independently within Ampharetidae. However, eight described species of ampharetids from CBEs were not included in the present phylogeny (Table 1). Based on morphological characteristics, three of these (Anobothrus apaleatus, Grassleia hydrothermalis and Pavelius makranensis) probably fall within the clades named here as Clades A1 and A2, and Amage benhami is probably related to clade C1 or C2. Glypanostomum bilabiatum and Glyphanostomum holthei are the only two species in the genus Glyphanostomum (which has six described species) adapted to CBEs [24, 26], and the position of the type species, G. pallescens, in the phylogenetic analysis presented here indicates that these species represent an additional clade adapted to CBEs. Decemunciger apalea and Endecamera palea are both the type species of a monotypic genus [28]. Kongsrud et al. [23] suggested that Decemunciger might be related to Paramytha, and a comparison of our data with COI sequences of Decemunciger sp. from GenBank (accession nos. KY972414–16) supports this suggestion. Endecamera has no clear morphological similarities to other ampharetid genera [84]. Although the phylogenetic position of these species cannot be resolved without more data, the inference that ampharetids have adapted into CBEs four times independently must be a minimum estimate.

To our knowledge, multiple independent adaptations into CBEs within one major clade has, to date, only been shown for Dorvilleidae [89]. Since most of the phylogenetic studies on fauna from CBEs have focused on symbiotrophic taxa (e.g. [12, 13, 17]), it is possible that this pattern is more common in heterotrophic animals, such as Ampharetidae and Dorvilleidae. Although the adaptation to CBEs has happened several times in Ampharetidae, there are multiple species in each of the specialized clades, which shows that the colonization of CBEs leads to a subsequent diversification. This implies that the ancestor of these clades has acquired a novel adaptation enabling the worms to diversify within CBEs, possibly related to tolerance of the chemical environment in CBEs or to a bacterivore diet.

There are several habitats represented in each of the specialized clades, which shows that evolutionary shifts between CBEs are common within Ampharetidae. The low number of species in some clade makes the inference of ancestral habitats ambiguous, but three habitat transitions are recovered: two from vent to vent and seep, and one from seep to sedimented vent (Fig. 5). The direction of colonization from vent to seep appears to be rare as most phylogenetic studies of taxa with representatives from different CBEs show that vent taxa evolved from fall or seep-dwelling ancestors [14, 15, 18, 21, 22]. In both clades A2 and C2, the shift between vent and seep habitats is associated with sedimented vents, which indicates a potential role of sedimented vents in transitions between different CBEs in Ampharetidae. Clade A3 also shows a link between sedimented vents and organic falls. However, three of the four species recorded from sedimented vents do not use the sediments as substratum, but are associated with structure-forming animals (Table 1). This indicates that the link between these two habitats might not lie in the sediment as substratum, but rather with the interaction between the sediments and vent fluids, which makes them more similar to seep fluids [90, 91]. This could again be related to the trophic ecology of the ampharetids, since fluid composition shapes the microbial community that the worms feed on [78].

Conclusions

The review of habitat use of ampharetids in CBEs did not reveal any apparent differences in substratum use or temperature tolerance which could explain their habitat specificity, but differences in depth may limit some species to a certain habitat. Trophic specialization or competition were also identified as potential factors influencing habitat-specificity. However, data on the ecology of Ampharetidae is still limited, and future studies on trophic ecology and biological interactions of ampharetids in CBEs are needed to fully understand which factors are shaping their distributions and habitat use.

The phylogeny presented here shows that adaptation into CBEs has happened at least four times within Ampharetidae, with subsequent diversification within CBEs. Multiple colonizations of CBEs within a family is unusual, but we hypothesize that this might be more common among heterotrophic taxa. Habitat shifts between CBEs are common in Ampharetidae, and the phylogeny indicates a potential role of sedimented vents in the transition between vent and seep habitats. The high number of ampharetid species described from CBEs recently, and the putative new species included in this phylogeny, indicate that there is a lot of diversity still to be discovered. This study provides a molecular framework for future studies to build upon and identifies some ecological and evolutionary hypotheses to be tested as new data becomes available.

Abbreviations

- 16S:

-

mitochondrial 16S ribosomal DNA

- 18S:

-

nuclear 18S ribosomal DNA

- 28S:

-

nuclear 28S ribosomal DNA

- CBE:

-

Chemosynthesis based ecosystem

- COI:

-

mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I

- SIO-BIC:

-

Scripps Oceanography Benthic Invertebrate Collection

- ZMBN:

-

Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen

References

Childress JJ, Fisher CR. The biology of hydrotermal vent animals: physiology, biochemistry and autotrophic symbioses. Oceanogr Mar Biol. 1992;30:337–441.

Thurber AR, Levin LA, Rowden AA, Sommer S, Linke P, Kröger K. Microbes, macrofauna, and methane: a novel seep community fueled by aerobic methanotrophy. Limnol Oceanogr. 2013;58:1640–56.

Tunnicliffe V, Juniper SK, Sibuet M. Reducing environments of the deep-sea floor. In: Tyler PA, editor. Ecosystems of the deep oceans. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2003. p. 81–110.

Bernardino AF, Levin LA, Thurber AR, Smith CR. Comparative composition, diversity and trophic ecology of sediment macrofauna at vents, Seeps and Organic Falls. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33515.

Levin LA, Orphan VJ, Rouse GW, Rathburn AE, Ussler W, Cook GS, Goffredi SK, Perez EM, Waren A, Grupe BM, et al. A hydrothermal seep on the Costa Rica margin: middle ground in a continuum of reducing ecosystems. Proc R Soc B. 2012;279:2580–8.

Portail M, Olu K, Escobar-Briones E, Caprais JC, Menot L, Waeles M, Cruaud P, Sarradin PM, Godfroy A, Sarrazin J. Comparative study of vent and seep macrofaunal communities in the Guaymas Basin. Biogeosciences. 2015;12:5455–79.

Kiel S. A biogeographic network reveals evolutionary links between deep-sea hydrothermal vent and methane seep faunas. Proc R Soc B. 2016;283:20162337.

Van Dover CL, German CR, Speer KG, Parson LM, Vrijenhoek RC: Evolution and biogeography of deep-sea vent and seep invertebrates. Science 2002;295:1253–1257.

Wolff T: Composition and endemism of the deep-sea hydrothermal vent fauna. Cah Biol Mar. 2005;46:97–104.

Watanabe H, Fujikura K, Kojima S, Miyazaki J-I, Fujiwara Y. Japan: vents and seeps in close proximity. In: Kiel S, editor. The vent and seep biota. Netherlands: Springer; 2010. p. 379–401.

Olu K, Cordes EE, Fisher CR, Brooks JM, Sibuet M, Desbruyères D. Biogeography and potential exchanges among the Atlantic equatorial belt cold-seep faunas. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11967.

Thubaut J, Puillandre N, Faure B, Cruaud C, Samadi S. The contrasted evolutionary fates of deep-sea chemosynthetic mussels (Bivalvia, Bathymodiolinae). Ecol Evol. 2013;3:4748–66.

Johnson SB, Krylova EM, Audzijonyte A, Sahling H, Vrijenhoek RC. Phylogeny and origins of chemosynthetic vesicomyid clams. Syst Biodivers. 2016:1–15.

Decker C, Olu K, Cunha RL, Arnaud-Haond S. Phylogeny and diversification patterns among Vesicomyid bivalves. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33359.

Jones WJ, Won YJ, Maas PAY, Smith PJ, Lutz RA, Vrijenhoek RC. Evolution of habitat use by deep-sea mussels. Mar Biol. 2006;148:841–51.

Lorion J, Kiel S, Faure B, Kawato M, Ho SYW, Marshall B, Tsuchida S, Miyazaki J, Fujiwara Y. Adaptive radiation of chemosymbiotic deep-sea mussels. Proc R Soc B. 2013;280:20131243.

Li Y, Kocot KM, Whelan NV, Santos SR, Waits DS, Thornhill DJ, Halanych KM. Phylogenomics of tubeworms (Siboglinidae, Annelida) and comparative performance of different reconstruction methods. Zool Scr. 2016;46:200–13.

Schulze A, Halanych KM. Siboglinid evolution shaped by habitat preference and sulfide tolerance. Hydrobiologia. 2003;496:199–205.

Vrijenhoek RC, Johnson SB, Rouse GW. A remarkable diversity of bone-eating worms (Osedax; Siboglinidae; Annelida). BMC Biol. 2009;7:74.

Distel DL, Baco AR, Chuang E, Morrill W, Cavanaugh C, Smith CR. Marine ecology - do mussels take wooden steps to deep-sea vents? Nature. 2000;403:725–6.

Roterman CN, Copley JT, Linse KT, Tyler PA, Rogers AD. The biogeography of the yeti crabs (Kiwaidae) with notes on the phylogeny of the Chirostyloidea (Decapoda: Anomura). Proc R Soc B. 2013;280:20130718.

Yang J-S, Lu B, Chen D-F, Yu Y-Q, Yang F, Nagasawa H, Tsuchida S, Fujiwara Y, Yang W-J. When did decapods invade hydrothermal vents? Clues from the western Pacific and Indian oceans. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:305–9.

Kongsrud JA, Eilertsen MH, Alvestad T, Kongshavn K, Rapp HT. New species of Ampharetidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from the Arctic Loki Castle vent field. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2017;137:232–45.

Reuscher MG, Fiege D. Ampharetidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from cold seeps off Pakistan and hydrothermal vents off Taiwan, with the description of three new species. Zootaxa. 2016;4139:197–208.

Stiller J, Rousset V, Pleijel F, Chevaldonné P, Vrijenhoek RC, Rouse GW. Phylogeny, biogeography and systematics of hydrothermal vent and methane seep Amphisamytha (Ampharetidae, Annelida), with descriptions of three new species. Syst Biodivers. 2013;11:35–65.

Reuscher M, Fiege D, Wehe T. Four new species of Ampharetidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from Pacific hot vents and cold seeps, with a key and synoptic table of characters for all genera. Zootaxa. 2009:1–40.

Queirós JP, Ravara A, Eilertsen MH, Kongsrud JA, Hilário A. Paramytha ossicola sp. nov. (Polychaeta, Ampharetidae) from mammal bones: reproductive biology and population structure. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2017;137:349–58.

Zottoli RA. Two new genera of deep sea polychaete worms of the family Ampharetidae and the role of one species in deep sea ecosystems. Proc Biol Soc Wash. 1982;95:48–57.

Gebruk AV, Krylova EM, Lein AY, Vinogradov GM, Anderson E, Pimenov NV, Cherkashev GA, Crane K. Methane seep community of the Håkon Mosby mud volcano (the Norwegian Sea): composition and trophic aspects. Sarsia. 2003;88:394–403.

Zottoli RA. Amphisamytha galapagensis, a new species of ampharetid polychaete from the vicinity of abyssal hydrothermal vents in the Galapagos rift, and the role of this species in rift ecosystems. Proc Biol Soc Wash. 1983;96:379–91.

McHugh D, Tunnicliffe V. Ecology and reproductive biology of the hydrothermal vent polychaete Amphisamytha galapagensis (Ampharetidae). Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1994;106:111–20.

Sommer S, Linke P, Pfannkuche O, Niemann H, Treude T. Benthic respiration in a seep habitat dominated by dense beds of ampharetid polychaetes at the Hikurangi margin (New Zealand). Mar Geol. 2010;272:223–32.

Fontanillas E, Galzitskaya OV, Lecompte O, Lobanov MY, Tanguy A, Mary J, Girguis PR, Hourdez S, Jollivet D. Proteome evolution of deep-sea hydrothermal vent alvinellid polychaetes supports the ancestry of thermophily and subsequent adaptation to cold in some lineages. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:279–96.

PANGAEA. Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science. Expeditions. https://http://www.pangaea.de/expeditions/. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Read G: Ampharetidae Malmgren, 1866. 2017. In: Read G, Fauchald K, editors. World Polychaeta database. http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=981. Accessed 30 March 2017.

Cunha MR, Rodrigues CF, Génio L, Hilário A, Ravara A, Pfannkuche O. Macrofaunal assemblages from mud volcanoes in the Gulf of Cadiz: abundance, biodiversity and diversity partitioning across spatial scales. Biogeosciences. 2013;10:2553–68.

Struck TH, Pursche G, Halanych KM. Phylogeny of Eunicida (Annelida) and exploring data congruence using a partition addition bootstrap alteration (PABA) approach. Syst Biol. 2006;55:1–20.

Passamaneck YJ, Schander C, Halanych KM. Investigation of molluscan phylogeny using large-subunit and small-subunit nuclear rRNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:25–38.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7.

MAFFT. Version 7. Online version. http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/. Accessed 20 March 2017

Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–80.

Katoh K, K-i K, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:511–8.

Castresana J: Gblocks server. 2002. http://molevol.cmima.csic.es/castresana/Gblocks_server.html. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56:564–77.

Kück P, Meusemann K, Dambach J, Thormann B, von Reumont BM, Wägele JW, Misof B. Parametric and non-parametric masking of randomness in sequence alignments can be improved and leads to better resolved trees. Front Zool. 2010;7:10.

Xia X. DAMBE5: a comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1720–8.

Xia X, Xie Z, Salemi M, Chen L, Wang Y. An index of substitution saturation and its application. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003;26:1–7.

Xia X, Lemey P. Assessing substitution saturation with DAMBE. In: Lemey P, Salemi M, Vandamme AM, editors. The phylogenetic handbook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 615–30.

Vaidya G, Lohman DJ, Meier R. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics. 2011;27:171–80.

Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–21.

Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SY, Guindon S. PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1695–701.

Lanfear R, Frandsen PB, Wright AM, Senfeld T, Calcott B. PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;34:772–3.

Stamatakis A: The RAxML 8.2.X Manual. 2016. https://sco.h-its.org/exelixis/web/software/raxml/. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–3.

Silvestro D, Michalak I. raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org Divers Evol. 2012;12:335–7.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–4.

Lifeportal. University of Oslo. https://lifeportal.uio.no. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Jones G: STACEY package documentation: species delimitation and species tree estimation with BEAST2. 2014. http://www.indriid.com/software.html. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Jones G. Algorithmic improvements to species delimitation and phylogeny estimation under the multispecies coalescent. J Math Biol. 2017;74:447–67.

Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kühnert D, Vaughan T, C-H W, Xie D, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003537.

Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T: Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE). 2010:1–8.

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ: Tracer v1.5. 2009. http://beast.community/tracer. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Rambaut A: FigTree. Version 1.4.0. 2012. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Jones G: Software page. 2017. http://www.indriid.com/software.html. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Jones G, Aydin Z, Oxelman B. DISSECT: an assignment-free Bayesian discovery method for species delimitation under the multispecies coalescent. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:991–8.

Kolde R: pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. 2015. https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html. Accessed 20 March 2017.

Maddison WP, Maddison DR: Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. 2017. http://mesquiteproject.org. Accessed 20 April 2017.

Benham WB. Polychaeta. British Antarctic 'Terra Nova' expedition natural history reports. Zoology. 1927;7(2):47–182.

Marshall BA, Tracey D. First evidence for deep-sea hot venting or cold seepage in the Ross Sea (Bivalvia: Vesicomyidae). Nautilus Greenville then Sanibel. 2015;129:140–1.

Grassle JF, Petrecca R. Soft-sediment hydrothermal vent communities of Escanaba trough. US Geol Surv Bull. 1994;2022:327–35.

Solís-Weiss V. Grassleia hydrothermalis, a new genus and species of Ampharetidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from the hydrothermal vents off the Oregon coast (U.S.A.) at Gorda ridge. Proc Biol Soc Wash. 1993;106(4):661–5.

Reuscher M, Fiege D, Wehe T. Terebellomorph polychaetes from hydrothermal vents and cold seeps with the description of two new species of Terebellidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) representing the first records of the family from deep-sea vents. J Mar Biol Assoc U K. 2012;92:997–1012.

Herzig PM, Hannington MD, Stoffers P, Becker K-P, Drischel M, Franklin J, Franz L, Gemmell JB, Hoeppner B, Horn C, et al. Petrology, gold mineralization and biological communities at shallow submarine volcanoes of the New Ireland fore-arc (Papua New Guinea): preliminary results of R/V Sonne cruise SO-133. InterRidge News. 1998;7:34–8.

Stecher J, Tunnicliffe V, Türkay M. Population characteristics of abundant bivalves (Mollusca, Vesicomyidae) at a sulphide-rich seafloor site near Lihir Island, Papua New Guinea. Can J Zool. 2003;81:1815–24.

Lee RW. Thermal tolerances of deep-sea hydrothermal vent animals from the Northeast Pacific. Biol Bull. 2003;205:98–101.

Portail M, Olu K, Dubois SF, Escobar-Briones E, Gelinas Y, Menot L, Sarrazin J. Food-web complexity in Guaymas Basin hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162263.

Steen IH, Dahle H, Stokke R, Roalkvam I, Daae F-L, Rapp HT, Pedersen RB, Thorseth IH. Novel barite chimneys at the Loki's castle vent field shed light on key factors shaping microbial communities and functions in hydrothermal systems. Front Microbiol. 2015;6

Govenar B, Fisher CR, Shank TM. Variation in the diets of hydrothermal vent gastropods. Deep-Sea Res II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2015;121:193–201.

Levin LA, Ziebis W, Mendoza GF, Bertics VJ, Washington T, Gonzalez J, Thurber AR, Ebbe B, Lee RW. Ecological release and niche partitioning under stress: lessons from dorvilleid polychaetes in sulfidic sediments at methane seeps. Deep-Sea Res II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2013;92:214–33.

Desbruyères D, Laubier L. Paralvinella grasslei, new genus, new species of Alvinellinae (Polychaeta: Ampharetidae) from the Galapagos rift geothermal vents. Proc Biol Soc Wash. 1982;95:484–94.

Desbruyeres D, Laubier L. Alvinella pompejana gen. sp. nov., Ampharetidae aberrant des sources hydrothermales de la ride Est-Pacifique. Oceanol Acta. 1980;3:267–74.

Desbruyères D, Laubier L. Les Alvinellidae, une famille nouvelle d’annélides polychètes inféodées aux sources hydrothermales sous-marines: systématique, biologie et écologie. Can J Zool. 1986;64:2227–45.

Jirkov IA. Discussion of taxonomic characters and classification of Ampharetidae (Polychaeta). Italian Journal of Zoology. 2011;78:78–94.

Salazar-Vallejo SI, Hutchings P. A review of characters useful in delineating ampharetid genera (Polychaeta). Zootaxa. 2012;3402:45–53.

Jirkov IA. [Polychaeta of the Arctic Ocean] Polikhety severnogo Ledovitogo Okeana. Moskva: Yanus-K; 2001.

Reuscher M, Bellan G: Amage. 2013. In: Read G, Fauchald K, editors. World Polychaeta database. http://marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=129153. Accessed 28 March 2017.

Sukumaran J, Knowles LL. Multispecies coalescent delimits structure, not species. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2017;114:1607–12.

Thornhill DJ, Struck TH, Ebbe B, Lee RW, Mendoza GF, Levin LA, Halanych KM. Adaptive radiation in extremophilic Dorvilleidae (Annelida): diversification of a single colonizer or multiple independent lineages? Ecol Evol. 2012;2:1958–70.

Von Damm KL, Edmond JM, Measures CI, Grant B. Chemistry of submarine hydrothermal solutions at Guaymas Basin, gulf of California. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1985;49:2221–37.

Baumberger T, Früh-Green GL, Thorseth IH, Lilley MD, Hamelin C, Bernasconi SM, Okland IE, Pedersen RB. Fluid composition of the sediment-influenced Loki’s castle vent field at the ultra-slow spreading Arctic Mid-Ocean ridge. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2016;187:156–78.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ken Halanych and Viktoria Bogantes for material from the Antarctic, Marina Cunha, Ascensão Ravara and Ana Hilário for material from the Gulf of Cadiz and Setùbal Canyon, Lenaick Menot for material from the Snake Pit vent field, Andrew Thurber for material from the Hikurangi Margin seeps, Igor Jirkov for the material of Pavelius uschakovi, the MAREANO project for material from Norwegian waters, the German Centre for Marine Biodiversity Research (DZMB) and Karin Meißner for material from Icelandic waters and the North Sea, the EAF-Nansen Programme, the Gulf of Guinea LME (GCLME) and the Canary Current LME (CCLME) for material collected in NW African waters. We also thank Bob Vrijenhoek for inviting GWR on cruises and the captain and crew of the R/V Western Flyer and pilots of the ROVs Tiburon and Doc Ricketts (Monterey Bay Aquarium and Research Institute) who enabled the collection of ampharetids from the East Pacific. Thanks also to Nataliya Budaeva, Solveig Thorkildsen, Morten Stokkan and Louise Lindblom for their help with the labwork, Endre Willasen for advice on the phylogenetic analyses, Graham Jones for his help with the Stacey analyses, Katrine Kongshavn for her help with production of the locality-map, and to Joana B. Xavier and Caroline Armitage for valuable discussions and input on the manuscript. We also want to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Availability of data and material

Sequence data produced for this study have been deposited in GenBank, see Additional file 2 for accession numbers. Geographic coordinates of records of Ampharetids in chemosynthesis-based ecosystems and DNA sequence alignments are available in a Figshare repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5519044).

Funding

This work has been supported by the NFR through Centre for Geobiology (project number 179560), the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters and The Norwegian Deep Sea Program (the taxonomy fund), the Norwegian Taxonomy Initiative (project ‘Polychaete diversity in the Norwegian Sea - from coast to the deep sea’ – PolyNor: project number 70184227) through the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre, and the JRS Biodiversity Foundation. DNA-barcode data generated in this project is part of the Norwegian Barcode of Life (NorBOL) project funded by the Research Council of Norway and the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre. The project was also funded in part by a student grant from the Meltzer Foundation awarded to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MHE contributed to study design, performed most of the DNA sequencing, phylogenetic analyses, and wrote the manuscript. JAK contributed to study design, identified specimens, subsampled for DNA work and helped with taxonomic aspects of the manuscript. TA identified specimens and subsampled for DNA work. JS performed DNA sequencing of 28S from Amphisamytha spp. and identified material from the East Pacific. GR contributed with material from the East Pacific and details on the habitat of Amphisamytha spp. HTR contributed to the study design, coordinated the study, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval is not required for the collection and investigation of the morphology and DNA of annelid worms.

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Review table of habitat of Ampharetidae in CBEs including references of the literature included in the review and taxonomic authorities for all species (XLSX 22 kb)

Additional file 2:

List of specimens included in phylogenetic analysis with sampling data and GenBank accession numbers. Sequences that were produced for this study are highlighted in bold. Abbreviations: AuM, Australian Museum; AUM, Auburn University Museum, USA; DBUA, Biological Research Collection of Marine Invertebrates of Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal; ; NTNU-VM, Department of Natural History, NTNU University Museum, Trondheim, Norway; NZ, NIWA, New Zealand; SIO-BIC, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Benthic Invertebrate Collection, USA; SMF, Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt, Germany; ZMBN, Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen, Norway (XLSX 109 kb)

Additional file 3:

Best fit models for each partition as suggested by PartitionFinder. Shown for the complete dataset and the datasets of Clade A and Clade C. COI 1, 2 and 3 refers to first, second and third codon position of COI, but third codon position was not included in analyses due to saturation (XLSX 36 kb)

Additional file 4:

COI gene tree of the complete dataset. The tree shown was inferred in MrBayes, branch labels are showing posterior probabilities and bootstrap values (PP/BS). Support values lower than 0.75/50 are not shown. An asterix (*) indicates PP = 1 and BS = 95–100, − indicates the node was not recovered in the best maximum likelihood tree. Identical sequences were removed prior to analyses (TIFF 20491 kb)

Additional file 5:

16S gene tree of the complete dataset. The tree shown was inferred in MrBayes, branch labels are showing posterior probabilities and bootstrap values (PP/BS). Support values lower than 0.75/50 are not shown. An asterix (*) indicates PP = 1 and BS = 95–100, − indicates the node was not recovered in the best maximum likelihood tree. Identical sequences were removed prior to analyses. (TIFF 21529 kb)

Additional file 6:

18S gene tree of the complete dataset. The tree shown was inferred in MrBayes, branch labels are showing posterior probabilities and bootstrap values (PP/BS). Support values lower than 0.75/50 are not shown. An asterix (*) indicates PP = 1 and BS = 95–100, − indicates the node was not recovered in the best maximum likelihood tree. Identical sequences were removed prior to analyses. (TIFF 18611 kb)

Additional file 7:

28S gene tree of the complete dataset. The tree shown was inferred in MrBayes, branch labels are showing posterior probabilities and bootstrap values (PP/BS). Support values lower than 0.75/50 are not shown. An asterix (*) indicates PP = 1 and BS = 95–1, − indicates the node was not recovered in the best maximum likelihood tree. Identical sequences were removed prior to analyses. (TIFF 18438 kb)

Additional file 8:

Alignment statistics for the three datasets (complete, Clade A and Clade C) (XLSX 39 kb)

Additional file 9:

Heatmap based on the output from Stacey showing the posterior probability of two specimens belonging to the same species. The probability matrix was calculated from the output of the Stacey analysis (see Methods – Phylogenetic analyses). Colors represent posterior probability values: 0–0.8 – blue, 0.8–0.9 – yellow, 0.9–0.95 – orange, 0.95–1 – red. Species names are abbreviated by the tree first letters of the genus and species epithet (PDF 315 kb)

Additional file 10:

Heatmap based on the output from Stacey showing the posterior probability of two specimens belonging to the same species. The probability matrix was calculated from the output of the Stacey analysis (see Methods – Phylogenetic analyses). Colors represents posterior probability values: 0–0.8 – blue, 0.8–0.9 – yellow, 0.9–0.95 – orange, 0.95–1 – red. Species names are abbreviated by the tree first letters of the genus and species epithet (PDF 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Eilertsen, M.H., Kongsrud, J.A., Alvestad, T. et al. Do ampharetids take sedimented steps between vents and seeps? Phylogeny and habitat-use of Ampharetidae (Annelida, Terebelliformia) in chemosynthesis-based ecosystems. BMC Evol Biol 17, 222 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-1065-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-1065-1