Abstract

Background

The tribe Coccinellini is a group of relatively large ladybird beetles that exhibits remarkable morphological and biological diversity. Many species are aphidophagous, feeding as larvae and adults on aphids, but some species also feed on other hemipterous insects (i.e., heteropterans, psyllids, whiteflies), beetle and moth larvae, pollen, fungal spores, and even plant tissue. Several species are biological control agents or widespread invasive species (e.g., Harmonia axyridis (Pallas)). Despite the ecological importance of this tribe, relatively little is known about the phylogenetic relationships within it. The generic concepts within the tribe Coccinellini are unstable and do not reflect a natural classification, being largely based on regional revisions. This impedes the phylogenetic study of important traits of Coccinellidae at a global scale (e.g. the evolution of food preferences and biogeography).

Results

We present the most comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of Coccinellini to date, based on three nuclear and one mitochondrial gene sequences of 38 taxa, which represent all major Coccinellini lineages. The phylogenetic reconstruction supports the monophyly of Coccinellini and its sister group relationship to Chilocorini. Within Coccinellini, three major clades were recovered that do not correspond to any previously recognised divisions, questioning the traditional differentiation between Halyziini, Discotomini, Tytthaspidini, and Singhikaliini. Ancestral state reconstructions of food preferences and morphological characters support the idea of aphidophagy being the ancestral state in Coccinellini. This indicates a transition from putative obligate scale feeders, as seen in the closely related Chilocorini, to more agile general predators.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the classification of Coccinellini has been misled by convergence in morphological traits. The evolutionary history of Coccinellini has been very dynamic in respect to changes in host preferences, involving multiple independent host switches from different insect orders to fungal spores and plants tissues. General predation on ephemeral aphids might have created an opportunity to easily adapt to mixed or specialised diets (e.g. obligate mycophagy, herbivory, predation on various hemipteroids or larvae of leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae)). The generally long-lived adults of Coccinellini can consume pollen and floral nectars, thereby surviving periods of low prey frequency. This capacity might have played a central role in the diversification history of Coccinellini.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ladybirds (Coccinellidae) are a well-defined monophyletic group of small to medium sized beetles of the superfamily Coccinelloidea, the superfamily formerly known as the Cerylonid Series within the superfamily Cucujoidea [1,2,3]. The relationships between the currently recognized 15 families of Coccinelloidea are not well understood, but comprehensive molecular phylogenetic analyses of Coccinelloidea [2] suggested that Eupsilobiidae, a mycophagous group of small brown beetles, previously included as a subfamily of Endomychidae [4, 5], are the sister group of Coccinellidae. Coccinellidae, which comprises 360 genera and about 6000 species world-wide, is by far the largest family of coccinelloid beetles and, with the notable exception of the parasitic Bothrideridae, the only predominantly predatory lineage of Coccinelloidea. The ancestor of Coccinellidae presumably lived in the Jurassic (~ 150 Mya [6]) and even a Permian-Triassic origin of Coccinelloidea has been suggested [7]. The development of a predatory life style in the ancestor of Coccinellidae, was possibly a relevant event for the evolutionary history of this beetle lineage, with herbivory, sporophagy and pollenophagy being derived from this predatory mode of life.

Most of the traditional classifications of Coccinellidae [8,9,10] recognize six or seven subfamilies (i.e., Chilocorinae, Coccidulinae, Coccinellinae, Epilachninae, Scymninae, Sticholotidinae, and sometimes Ortaliinae, each with numerous tribes). The foundation of this system was developed by Sasaji [11, 12] based on comparative morphological analyses of adults and larvae from species of the Palaearctic Region, mostly Japan. Kovář [9] presented a major modification of Sasaji’s classification on a global scale, recognizing seven subfamilies and 38 tribes. The classifications proposed by Sasaji [11] and Kovář [9] were found to be largely artificial and phylogenetically unacceptable by Ślipiński [13], who argued for a basal split of Coccinellidae into two subfamilies, Microweiseinae and Coccinellinae, with the latter containing most of the tribes, including Coccinellini. Six subsequent papers on the molecular phylogeny of the family Coccinellidae [14,15,16,17] and Cucujoidea [2, 3] corroborated the monophyly of the family and of the two subfamilies recognized by Ślipiński [13]. They also provided strong evidence for the monophyly of Coccinellini. Based on results of phylogenetic analyses of molecular data and a combination of molecular and morphological data from Coccinellidae, Ślipiński and Tomaszewska [18] and Seago et al. [17] formalized the taxonomic status of Coccinellini as a tribe within the broadly defined Coccinellinae.

Coccinellini, commonly referred to as ‘true ladybirds’, comprises 90 genera and over 1000 species world-wide. The tribe includes many charismatic and easily recognised beetles that are often seen on aphid-infested trees and shrubs in the natural and urban landscapes. It is also one of the most frequently studied groups of beetles, the subject of thousands of peer-reviewed scientific papers on biology, genetics, colour polymorphism, physiology and biological control, summarized in various influential books [19,20,21,22].

Coccinellini are generally viewed as predators of aphids, but their diet is much more diverse and often includes other hemipterous insects (i.e., heteropterans, psyllids), beetle and moth larvae, pollen, fungal spores, and even plant tissues. Coccinellini display extraordinary morphological diversity in all life stages and are among the most conspicuously and attractively coloured beetles, often bearing strikingly red or yellow elytra, with contrasting black spots, stripes, or fasciae (Figs. 1 and 2). These vivid colours are aposematic, warning predators that these beetles are distasteful and produce noxious or poisonous alkaloids [23] excreted as droplets of fluid during a ‘reflex bleeding’ behaviour. Many species of Coccinellini are also of great economic importance as biological control agents or unwanted invaders on a scale of entire continents (e.g., multicoloured Asian ladybird beetle, Harmonia axyridis [24]).

Representative spectrum of Coccinellini morphologies and feeding habits: a Coccinella septempunctata, adult feeding on aphids; b Coelophora variegata, adult feeding on aphids; c Heteroneda reticulata, pupa being parasitized by a phorid fly; d Cleobora mellyi, larva feeding on larva of Paropsis charybdis (Chrysomelidae); e Halyzia sedecimguttata, larva feeding on mildew; f Harmonia conformis, adult feeding on psyllids; g, h Bulaea lichatschovi, larva and adult, feeding on leaves and buds of Bassia prostrata. Photographs credits: a, b Paul Zborowski; c Melvyn Yeo; d Andrew Bonnitcha; e Gilles San Martin; f Nick Monaghan; g, h Maxim Gulyaev

Representative spectrum of Coccinellidae morphologies and feeding habits. a Psyllobora vigintiduopunctata, adult feeding on mildew; b Hippodamia variegata, adults feeding on pollen; c Scymnus sp., larva with dense waxy covering; d Harmonia axyridis, larva showing droplets of haemolymph at abdominal segments; e Harmonia axyridis, pupa with nymph of parasitic mite; f Anatis ocellata, adult with excreted droplets of haemolymph; g Halyzia sedecimguttata, adult with excreted haemolymph droplets on legs; h Illeis galbula, adult, showing strongly expanded terminal maxillary palpomere; i Phrynocaria astrolabiana, female terminalia showing glands (indicated by arrows); j Archegleis kingi, pupa lateral showing gin traps between abdominal tergites (indicated by arrows). Photographs credits: a Jelle Devalez; b Nick Monaghan; c Paul Zborowski; d Gilles San Martin; e Bruce Marlin; f Remy Ware; g John Jeffery; h Steve Axford

Surprisingly, relatively little is known about the phylogenetic relationships and the evolutionary history of this ecologically important and species-rich beetle lineage. The phylogeny of the tribe has not been studied in detail and its subordinated taxonomic classification is largely regional and non-phylogenetic, impeding comparative analyses of important features of coccinellid evolution, such as host preferences, on a global scale. So far, published research on the evolutionary history of Coccinellidae has focussed on the phylogeny of the entire family and included only a very limited set of Coccinellini. The study by Magro et al. [15] included more species and genera of Coccinellini (i.e., 32 species, 15 genera) than any other investigation, but the authors’ taxon sampling was heavily focused on European species. Their data set differed from a smaller set of Asian taxa (24 species, 15 genera) analysed by Aruggoda et al. [16] and a similar sized but more global data set (23 species, 16 genera) by Robertson et al. [2]. In addition to the taxonomically different data sets, the molecular hypotheses put forth in the cited papers had very weak support especially at deeper nodes within Coccinellini, and each study recovered incongruent relationships among the genera. More comprehensive morphological and molecular research is required to improve the global classification of Coccinellini and to establish a reliable generic classification for this tribe.

Here we present molecular phylogenetic analyses based on a world-wide and taxonomically broad sampling of Coccinellini, representing all major lineages and analysing the phylogenetic signal of four genes (one mitochondrial and three nuclear) using Bayesian and Maximum-Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic approaches. The aims of our study are to: (1) assess the monophyly of Coccinellini; (2) generate the first comprehensive phylogenetic hypothesis about generic relationships within the tribe Coccinellini; (3) test if some formerly recognised tribes of Coccinellini (i.e., Discotomini, Halyziini, Singhikaliini, and Tytthaspidini) merit recognition as subtribes; and (4) reconstruct the evolution of selected morphological characters and of food preferences within Coccinellini.

Methods

Taxon sampling and morphology

We analysed 38 species of Coccinellini belonging to 32 of 90 genera. They represent all previously proposed tribes currently included in Coccinellini (i.e., Coccinellini – 23 of 67 genera, Discotomini – 1 of 5 genera, Halyziini – 3 of 8 genera, Singhikaliini – 1 genus (monotypic tribe), and Tytthaspidini (=Bulaeini) – 4 of 9 genera) and 14 outgroup species, representing a variety of coccinellid subfamilies and tribes, and two species of Corylophidae. Our taxon sampling was not designed to assess relationships within the family Coccinellidae, but was aimed at inferring the relationships within the tribe Coccinellini and tracing the evolution of morphological traits and food preferences. We selected species with known biology and food preferences, if tissue samples containing DNA were available to us. The biology of Seladia beltiana Gorham (former Discotomini) and Singhikalia duodecimguttata Xiao (former Singhikaliini) is unknown, but the examination of gut contents of two specimens of Seladia sp. revealed abundant fungal spores, suggesting that this species may be fungivorous (A. Ślipiński, personal observation). Gut contents of Singhikalia duodecimguttata Xiao from China and S. latemarginata (Bielawski) from Papua New Guinea showed a mixture of unrecognizable cuticular pieces and fungal conidia (A. Ślipiński, personal observation), which indicates a mixed or fungal diet.

We compiled a data matrix with essential information on food preference and the state of six morphological characters of adults and immatures for each species in our study (Additional file 1: Table S3). Morphological characters selected (adult pubescence, female colleterial glands [13], larval dorsal gland openings, larval wax secretions, and pupal gin traps) have been used as diagnostic characters for Coccinellini [8, 10, 12, 13] or (mandible type) used in discussions about the food preferred by adult beetles [25, 26] but none of these have been phylogenetically tested. Morphological characters were obtained from voucher specimens at the Australian National Insect Collection (CSIRO) and the literature [8, 9, 11]. The primary food preference (essential food source) of each species was established from the dissected guts of several representatives of each species and from the literature [8, 14, 21, 27,28,29,30,31,32].

DNA sequencing of target genes

DNA was extracted from ethanol preserved specimens following the standard protocol for animal tissues of the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit. Generally, one specimen per species was used for the extraction. Four nuclear and one mitochondrial gene fragments were amplified by PCR (i.e., two sections of carbamoylphosphate synthetase / aspartate transcarbamylase / dihydroorotase (CAD: CADMC and CADXM), topoisomerase I (TOPO), wingless (WGL), and cytochrome oxidase I (COI). These genes contrary to the widely used ribosomal genes (e.g. 18S, 28S) can be aligned with more accuracy. The amplification strategy [33], using degenerate primers with M13 (−21) / M13REV tails attached to the 5′ ends of the forward and the reverse primer, respectively. The primers had either been published previously [34] or were developed by us in context of the present study (CADXM2; Additional file 2: Table S1). Depending on the PCR yield, PCR products were either sequenced directly or re-amplified in a second and/or third PCR with hemi-nested and / or M13 primers. Initial PCRs were performed in 50-μL reaction volumes (32.8 μL of water, 5 μL of 10× buffer, 4 μL of 25 mM MgCl2, 2 μL of 10 mM dNTP mix, 2 μL of each 10 mM forward and reverse primer, 0.2 μL of 5 U/μL KAPA taq polymerase, 2 μL of template DNA) and a touch-down temperature profile that stepped from 55 °C down to 45 °C for conveniently amplifying with all primer pairs, irrespective of their specific binding temperature, 25 cycles with 94 °C for 30 s., 55 °C [−0.4 °C each cycle] for 30 s., and 72 °C, for 60 s. [+ 2 s. each cycle], followed by 13 cycles with 94 °C for 30 s., 45 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 120 s [+ 3 s. each cycle], followed by 72 °C for 600 s. [35]. Reamplifications also used 50-μl PCR reactions, but a simplified three-step hot-start temperature profile (22 cycles with 94 °C for 30 s., 50 °C for 30 s., and 72 °C for 60 s. [+ 2 s. each cycle], followed by 72 °C for 600 s.). All PCR products were bidirectionally sequenced using Sanger sequencing technology provided by LGC Genomics (Berlin, Germany). All raw reads were assembled with Geneious (v9.1.5; Biomatters, New Zealand [36]) and manually checked for sequencing errors, ambiguities and if necessary, manually edited.

Phylogenetic analyses

The coding DNA sequence of each gene was translated to the corresponding amino-acid sequence with the software Virtual Ribosome (version 2.0; [37]). The amino-acid sequences of each gene (CADMC, CADXM, TOPO, WGL, COI) were aligned using MAFFT (version 7.164b; [38]) and the original nucleotide sequences were mapped onto the alignments of amino-acid with a Perl script to generate a codon-based alignment of the nucleotide sequences (available upon request to AZ). The nucleotide and amino-acid multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) were visually inspected, and ambiguously aligned or gapped areas were excluded from downstream analyses (i.e., 194 of 3485 sites in the MSAs). All nucleotide sequences were queried against GenBank (NCBI [39]) using the software BLAST+ [40] to check for potential contaminations (e.g., gut content, fungi). We also inferred a neighbour-joining tree (PAUP*4.0b10, Linux, Sinauer Associates, MA, USA; [41]), from the nucleotide sequence of each gene fragment to check for potential cross-contaminations and sample swapping (the results are not shown because these were carried out on a more inclusive data set (Tomaszewska et al., in preparation)).

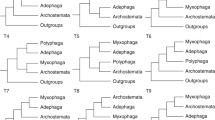

The five MSAs of nucleotides (CADMC: 693 bp, CADXM: 735 bp, TOPO: 678 bp, WGL: 420 bp, COI: 765 bp) were concatenated to form a supermatrix (five-fragment MSAs, Additional file 3: Supermatrix S1, 52 sequences, 3291 columns and 1571 informative sites) with a custom Perl script, that also generates character sets corresponding to the concatenated gene boundaries (available on request from AZ). To explore potential conflicting phylogenetic signal between the individual gene fragments in the concatenation, each one was excluded in turn from the MSAs and the resulting four-fragment MSAs were analysed using ML as implemented in RAxML (v8.0.26; [42]) (Additional file 4: Fig. S1a–e). The best ML topology and support values from 100 rapid bootstrap pseudo-replicates were compared to the analysis results of the five-fragment MSAs, not showing conflict among well-supported nodes (bootstrap values >85%) between topologies.

We inferred the optimal substitution models and partitioning scheme with PartitionFinder (version 1.1.1; [43]) using data blocks by gene fragment (CADMC, CADXM, TOPO, WGL, COI) and codon position as input, applying a greedy search approach with branch lengths linked across partitions and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The best partitioning scheme with corresponding substitution models (Additional file 5: Table S2) was then used to infer phylogenetic trees under the ML optimality criterion, as implemented in GARLI (version 2.01; [44]) (Additional file 6: Fig. S4). A total of 1080 heuristic tree searches were carried out on CSIRO compute cluster system, Pearcey (Dell PowerEdge M630), and the tree with the highest likelihood score selected. Bootstrap support values were obtained from 500 non-parametric bootstrap replicates with 10 heuristic tree search replicates each. Bootstrap values were mapped onto the ML tree using SumTrees (DendroPy version 3.12.2; [45]) and visualised with FigTree (version 1.4.2; https://github.com/rambaut/figtree, accessed May 8, 2015). The data was also analysed using a Bayesian method, as implemented in MrBayes (version 3.2.6; [46]) and the BEAGLE library (version 2.1.2; [47]). All model parameters, except branch lengths, remained unlinked, and two independent phylogenetic analyses were run with four chains each, sampling for 10 million generations every 1000th generation. The standard deviation of split frequencies was found to be <0.01, and convergence of the two runs was assessed using Tracer (version 1.6.0; [48]). The first 25% of the sampled trees were discarded as burn-in and the remaining sampled trees from the two runs were pooled. A 50% majority rule consensus tree with clade frequencies (posterior probabilities) was calculated with SumTrees and printed with FigTree (Additional file 7: Fig. S2).

To check for potentially detrimental influence of synonymous substitutions, the five-fragment MSA was fully degenerated with their respective genetic codes, using the software Degeneracy Coding (version 1.4; [49]). The resulting degenerated MSAs was analysed using RAxML with the same setting as for the four-fragment MSAs data set (which refers to the five gene fragment MSA less one gene fragment) (Additional file 8: Fig. S3).

Ancestral character state reconstruction

The ancestral character states of six discrete morphological and of one behavioural character (Additional file 1: Table S3) were inferred using the maximum parsimony (MP) and ML methods as implemented in Mesquite (version 3.1; [50]) and using the ML tree (Fig. 3) as backbone. The Mk1 model, also implemented in Mesquite, was used to calculate the ML probabilities of the ancestral states.

Phylogeny of Coccinellini based on ML best topology; number above branches show bootstrap support and posterior probability value above 0.50. Clades 1–3 of Coccinellini are discussed in the text. Taxa formerly classified in tribes Halyziini, Singhikaliini, Discotomini and Tytthaspidini are showed in different colour

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

The ML and Bayesian phylogenetic analyses of the five-fragment MSA resulted in identical topologies (Fig. 3, ML topology, log likelihood −55,518.302879 and Additional file 7: Fig. S2, the result from the Bayesian analysis). In both cases, the topology is mostly well supported, with 30 of 49 edges having a bootstrap support value of at least 75% and 35 of 49 edges having a posterior probability of at least 0.95 (both here subjectively regarded as “at least moderately supported”).

The ML analysis of the degeneracy-coded five-fragment MSA resulted in a similar topology with 21 of 49 edges at least moderately supported (Additional file 8: Fig. S3). These 21 edges were also all present in the above topology generated from the non-degenerated data (Fig. 3). Except for the sister-group relationship between Coccinellini and Chilocorini (bootstrap values of 76% and 60% with the degenerated and non-degenerated data, respectively), support values from the degenerated data are not much higher than those from analysing the non-degenerated data set. The higher bootstraps support values of the analysis with non-degenerated data and the topological congruence between results based on non-degenerated (Fig. 3) and degenerated data (Additional file 8: Fig. S3), for at least 21 edges with moderate to very strong support, are both indicative of the utility of the synonymous changes for the estimation of the Coccinellini phylogeny. The subsequent discussion, therefore, focuses on analyses of the non-degenerated data set (Fig. 3).

Coccinellini – Monophyly and sister relationship

To assess the support for the monophyly of Coccinellini, we used a comprehensive taxon sampling that represents all previously recognized tribes of Coccinellinae: Coccinellini, Discotomini, Halyziini, Singhikaliini, and Tytthaspidini (incl. Bulaeini). The outgroup includes twelve species of ladybirds classified as Microweiseinae (two species) and the Coccinellinae tribes Chilocorini (two species), Epilachnini (two species), Aspidimerini (two species), Noviini (one species), Sticholotidini (one species) and Coccidulini (two species). In addition, we included two species of fungivorous Corylophidae as more distant outgroup taxa within the superfamily Coccinelloidea [2] (Additional file 9: Table S4). The monophyly of Coccinellini sensu lato [13] was strongly supported with a bootstrap value of 100% and a posterior probability of 1.0.

Despite recent attempts to establish phylogenetic relationships within Coccinellidae, there is still no satisfactory resolution within the broadly defined subfamily Coccinellinae, that would lead to a stable tribal classification [17]. In previous studies, Chilocorini and Coccinellini were repeatedly recovered as monophyletic groups and as sister taxa of each other [2, 15, 17]. Our results from the ML and Bayesian analyses are consistent with these findings, but the support is weak (Bootstrap Support (BS) 60%, Posterior Probability (PP) 0.57; Fig. 3). Only moderate support was obtained when analysing the degenerated data set (BS 76%; Additional file 8: Fig. S3). Other previously-suggested phylogenetic positions of Coccinellini [14, 16] were not supported in our analyses.

Major clades within the tribe

Our analyses recovered three strongly supported clades within Coccinellini (Fig. 3), but relationships between these clades remain unresolved, as they are connected by short edges with low support values (i.e., BS < = 38 and PP < = 0.57). Clade 1 consists of species of the widespread genus Adalia and of the three New World genera Olla, Cycloneda, and Eriopis that are speciose in Central and South America [51]. Clades 2 and 3 comprise large radiations of primarily Old World species. Clade 2 is composed of species of the Holarctic genus Coccinella, of species of several genera formerly included in Tytthaspidini of species of the Holarctic genera Coleomegilla and Paranaemia (sometimes classified as Hippodamiini), and of species of the genera Oenopia, Cheilomenes, Aiolocaria and Synona. Within Clade 2, the genus Coccinella forms the sister group to the other species included in this clade. Clade 3 includes many genera. The Holarctic genera Aphidecta and Hippodamia and diverse Old World genus Harmonia constitute a well-supported group (BS 99%, PP 1.0). The Neotropical genus Seladia (formerly Discotomini) forms a moderately supported (BS 72%, PP 0.99) sister group to a phylogenetically unresolved complex of genera (BS 99%, PP 1.0) that includes the Old World Cleobora, Coelophora, Propylea, all genera of the former Halyziini, the Chinese species Singhikalia duodecimguttata (former Singhikaliini) (BS 99%, PP 1.0), and the widely-distributed Indo-Australian species Phrynocaria gratiosa. Interestingly, very large species of Coccinellini feeding on Hemiptera, Anatis ocellata (aphids) and Megalocaria (heteropterans), form a sister, albeit weakly supported (BS 52%, PP < = 0.50) group to powdery mildew fungi feeding taxa of the former Halyziini (Halyzia, Illeis and Psyllobora).

Ancestral state reconstruction

The results from the ancestral state reconstruction of adult pubescence, mandible type, female colleterial glands, larval dorsal gland openings, larval wax secretions, and pupal gin traps are presented on Additional files 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15: Figs. S5–S10. Both the ML and MP approaches to ancestral state reconstruction are congruent and revealed that the female colleterial glands (Additional file 10: Fig. S5) and pupal gin traps (Additional file 11: Fig. S6) were most likely present in the most recent common ancestor of Coccinellini, strongly supporting the monophyletic origin of this clade. The the common ancestor of Chilocorini and Coccinellini lacked adult dorsal pubescence (Additional file 14: Fig. S9), but it was regained in Singhikalia, the only known genus of Coccinellini with dorsal pubescence. The highly agile larvae of Coccinellini lack both defensive gland openings and protective waxes (Additional files 12 and 13: Figs. S7 and S8), and the ancestral state reconstruction analyses indicate that these features were lost in the most recent common ancestor of Chilocorini and Coccinellini. In our data set, larval and pupal waxes are present in only a few genera of Coccidulini (Rodolia, Sasajiscymnus, Rhyzobius) and appear to have evolved convergently (Additional file 13: Fig. S8).

With respect to the food preferences and associated structural modifications of the adult mouth parts (Additional file 15: Fig. S10), the ancestral state reconstruction analyses suggest that preying upon aphids is the ancestral state of Coccinellini, and that feeding on other Hemiptera, beetle larvae, mildew, spores, pollen and plant tissue has occurred multiple times independently.

Discussion

Phylogenetic analyses

In agreement with previously published molecular phylogenetic studies [2, 14,15,16,17] the monophyly of Coccinellini was resolved with high confidence in our analyses. Our studies are also consistent with the research based on nuclear and mitochondrial markers [2, 15, 17] recovering Chilocorini as the sister taxon of Coccinellini. The traditional idea of Coccinellini and Epilachnini being sister groups [9, 11], derived from studying morphological characters, remained unsupported by our analyses, as they were in other molecular analyses, which recovered Epilachnini at the base of the tree of Coccinellidae [15], within the taxa classified in Coccidulini (incl. Scymnini; [14, 16, 17]) or as sister to Coccidulini [52]. Our results (Fig. 4) suggest that the relatively large and aposematically coloured adults of aphid-feeding Coccinellini and herbivorous Epilachnini, both living on exposed surfaces and capable of strong reflex bleeding, are independently derived from smaller scale feeding ancestors. Epilachnini, which nest in our inferences within the “Coccidulinae” clade, retained densely pubescent bodies, while the last common ancestor of Coccinellini and Chilocorini lost this character (Additional file 14: Fig. S9), with the exception of the genus Singhikalia (former Singhikaliini), the only known pubescent Coccinellini. The genus Singhikalia is deeply nested within the tribe Coccinellini and represents an interesting case of convergence, possibly because it is mimicking local members of Epilachnini. Singhikalia ornata Kapur (India, Vietnam, Taiwan) and S. duodecimguttata Xiao (China) are reddish with black colour markings, while S. latemarginata (Bielawski) (Papua New Guinea) is almost entirely black. In this respect, all Singhikalia species match local members of Epilachnini very closely, to the extent that they are often found in the same series in museum collections, suggesting that they may co-occur in the same area and host plants.

The former tribe Halyziini forms strongly supported monophyletic group placed within the Clade 3 and comprises of speciose but very poorly defined Old World genera Coelophora, Calvia, Phrynocaria, and Propylea, the Asian Singhikalia, Old World Megalocaria, and species poor Holarctic genera Myzia and Anatis. In spite of taxon sampling differences the relationships between some of these taxa are in agreement with previous studies [2, 15, 16]. The second branch of the Clade 3 consists of Holarctic Aphidecta as a sister taxon to Harmonia and Hippodamia. The relationship between the last two genera has been recovered before [2, 16] but the placement of Aphidecta in this clade is a new position.

The exclusively Meso- and South American former tribe Discotomini is a poorly known group of 5 genera diagnosed by their strongly serrate or pectinate antennae. Their placement within traditional Coccinellinae has been uncertain and the molecular studies [2, 14] published so far placed Discotomini as a sister group to the remaining Coccinellini. The combined molecular and morphological analysis of Seago et al. [17] recovered Seladia as a sister group to the former Halyziini. We have recovered Seladia deeply embedded within Clade 3 at the base of large primarily Old World taxa, including former Halyziini.

The placement of the small Old World genera Tytthaspis and Bulaea in Coccinellini varied considerably in the past but their close affinity has been recognised by Iablokoff-Khnzorian [53], who pointed out similarities in male and female genitalia of several genera, later recognized as Tytthaspidini (= Bulaeini) by Kovář [9]. Most of the genera of former Tytthaspidini form strongly supported monophyletic group within the Clade 2 with Oenopia as the sister group, which is in agreement with Magro et al. [15].

The close relationships between Olla, Adalia and Cycloneda recovered in the Clade 1 has been suggested before [2, 15] but not the inclusion of the Neotropical Eriopis in this clade. Such arrangement suggests that the endemic New World genera and almost cosmopolitan Adalia have had long and independent evolutionary history from the much more diverse and speciose Coccinellini of the Old World.

As none of the previously recognised tribes, Discotomini, Halyziini, Singhikaliini, and Tytthaspidini, correspond with major clades within Coccinellini re-granting any of them subtribal status would render Coccinellini paraphyletic. Our results indicate that the newly-discovered clades, Clades 1–3 (Fig. 3), should receive recognition as formal taxonomic units, but it requires corroboration by analysis of a larger data set (Tomaszewska et al., in preparation).

Ancestral state reconstruction

Morphological characters

Coccinellini are generally recognised by relatively large adults having glabrous and convex dorsal surfaces, often with aposematic colouration, rather long and feebly clavate antennae inserted in front of large eyes, and strongly expanded “securiform” terminal maxillary palpomeres and ‘handle and blade’ female coxal plates [9, 11]. Most adults of Coccinellini can be distinguished by a combination of the above listed characters, but these are known to occur in taxa classified in other coccinellid groups. Ślipiński [13] expanded the list of diagnostic characters of Coccinellini, arguing that the presence of large paired reservoirs, associated with female terminalia called “colleterial glands” (Fig. 2i) and the development of the “gin traps” between abdominal tergites of the pupa (Fig. 2j) were unique developments within Coccinellidae and may constitute autapomorphies of Coccinellini. The functions of both these structures are not well understood but the secretion of the colleterial glands have been linked to mating behaviour or egg deposition in batches [54] while the “gin traps” significantly contribute to the pupal defence [55] facilitating a quick body flicking and by creating sharp edges between segments to pinch legs or entire bodies of predatory and parasitic invertebrates to discourage oviposition or predation (Figs. 1c, 2e).

To test the hypotheses by Ślipiński [13], we traced the evolution of pupal gin traps and female colleterial glands along our main ML tree with Mesquite. Using MP and ML methods applied to character evolution, we found that the above-mentioned characters originated in the common ancestor of Coccinellini (Additional files 10 and 11: Figs. S5 and S6) and consequently regard these characters as autapomorphies of the tribe.

In addition to the above traits, we investigated the development of larval dorsal abdominal glands (Additional file 12: Fig. S7) and protective larval waxes (Additional file 13: Fig. S8), present in many groups of ladybirds, but absent in Coccinellini. The function and homology of the dorsal glands in larvae of Coccinelloidea has not been thoroughly investigated, but paired openings on abdominal tergites are present in larvae of most Corylophidae, some Endomychidae and Coccinellidae [13]. They are absent in several ladybird groups, including Coccinellini. Adults of Coccinellidae are known to reflex-bleed by excreting droplets of alkaloid loaded hemolymph to deter or tangle apparent predators. This process is less studied in ladybird larvae, but the “bleeding” from the dorsal glands has been observed in Hyperaspis maindroni Sicard (J. Poorani, ICAR-NRCB, India, personal information) and Orcus bilunnulatus (Chilocorini, A. Ślipiński, personal observation). Larvae of several species of Coccinellini have not been observed to excrete hemolymph when disturbed (A. Ślipiński, personal observation). However, this process has been documented in larvae of Harmonia axyridis [56, 57], with droplets originating from intersegmental membranes on most abdominal segments, and more recently in larvae of Hippodamia variegata (O. Nedvěd, personal observation). It is unclear whether this is a species-specific behaviour or whether it has been overlooked in other Coccinellini.

The generalised carnivorous type of the adult mandible with bifid apex and molar part bearing two unequal teeth [9], that has originated in the ancestor of Coccinellidae has been carried over with very little modification in all predatory lineages of ladybirds with several independent origins of a single sharp apical incisor in specialized scale predators (Chilocorini, Microweiseinae). All known Coccinellini have apically bifid mandibles, used to pierce their prey, suck body fluids or to masticate the entire prey [26]. The mildew or microphagous feeding taxa (former Halyziini and Tytthaspidini) have the same type of mandible with additional serration along the incisor edge (Halyziini) or relatively stiff and comb like prostheca used to scoop the spores and pollen (Tytthaspidini). Interestingly, the mandible of sometimes phytophagous Bulaea does not differ from the microphagous type found in Tytthaspis, but markedly differs from strongly modified mandibles in phytophagous Epilachnini.

Food preferences

The evolution of food preferences in Coccinellidae is a very complex issue that has received much attention due to the importance of ladybirds as biological control agents [14, 58] and, more recently, due to the recognition of the environmental impact of introduced or invading ladybirds [59] on populations of native species. Some groups of ladybirds (e.g., Noviini, Stethorini, Telsimiini and most Chilocorini) show remarkably stable food preferences, feeding mostly on taxonomically narrow groups of invertebrates [22]. Coccidophagy, preying upon scale insects, which are gregarious organisms of limited mobility, has been evolved as an ancestral food preference in Coccinellidae [14, 17]. Coccidophagous coccinellids are often morphologically and physiologically adapted to a given prey [27, 60]. But even very specialized ladybirds feed and develop occasionally on a very different host (e.g., Stethorini, which are specialised on spider mites (Tetranychidae) can develop on whiteflies [61]).

Most species of Coccinellini are “general predators”, feeding in principle on aphids. Character-state reconstruction indicates that the transition from feeding on coccids to aphidophagy was acquired in the ancestor of Coccinellini (Fig. 4), but this feeding preference has independently arisen a few times in Coccinellinae (e.g., in Aspidimerini), in some genera of Coccidulini (e.g., Coccidula, Sasajiscymnus), Scymnini (Scymnus), and Platynaspidini (Platynaspis).

Coccinellini have diverse food preferences. While being primarily aphidophagous, they consume a broad spectrum of food that also includes other invertebrates, pollen, nectar, and often spores [14]. These opportunistic predators regularly cannibalize eggs and larvae of ladybirds, including those of their own species, and change diet depending on season and availability of prey. The gut contents of many species of Coccinellini examined during this study often consisted of predominantly sternorrhynchan Hemiptera mixed with pollen, and sometimes, with fungal spores.

Within Coccinellini, our results revealed repeated and phylogenetically independent food preference transitions from aphidophagy to other food sources (Fig. 4 and Additional file 16: Fig. S11): (a) to specialized and obligate mycophagy in the taxa classified in the former tribes Halyziini (Halyzia, Illeis, Psyllobora), feeding on hymenium and conidia of powdery mildew fungi (Erysiphales); (b) to a mixed diet in Bulaea, Coccinula and Tytthaspis (Tytthaspidini), with their known diet including spores of various Ascomycete fungi [32, 62], but also plant tissue (Bulaea), pollen (mainly of Asteraceae in Coccinula), acari and Thysanoptera (Tytthaspis); (c) to specialised predation on nymphs of the plataspid bugs in various phylogenetically independent lineages of some Megalocaria [63] and of Synona [64]; (d) to predation on larvae of Chrysomelidae in at least Asian Aiolocaria [65], Australian Cleobora mellyi [66] and the New World Neoharmonia sp. [67] (N. Vandenberg, USDA-Smithsonian, USA, personal communication; not included in our data), and (e) to psyllids (Psylloidea) as the essential food of Harmonia conformis at least in some geographic areas [68].

Conclusions

This study represents the first molecular phylogenetic analysis of the tribe Coccinellini with a world-wide taxonomic sampling. Our phylogenetic analyses revealed strong support for Coccinellini sensu lato [13] being monophyletic and a sister group to Chilocorini. Three major clades were identified within Coccinellini, suggesting that Old and New World taxa, especially South American Coccinellini, have probably evolved separately. None of the major clades correspond to the previously recognised tribes Discotomini, Halyziini, Singhikaliini, or Tytthaspidini. Consequently, we suggest that these taxonomic units should no longer be used. Further testing with more taxa, especially from South America, is required to corroborate the constitution of and relationships between the three major clades of Coccinellini proposed in this study. Our study also provides an understanding of the diversification of Coccinellini and character evolution within this tribe, particularly the evolution of food preferences. The switch from obligate coccidophagy to aphidophagy in ancestral Coccinellini was accompanied by larval changes (losing dorsal defensive glands and strong dorsal ornamentation) for increased agility, and the pupae shedding larval skins completely and exposing dorsal gin traps.

References

Crowson RA. The natural classification of the families of Coleoptera. London: Lloyd; 1955.

Robertson JA, Ślipiński A, Moulton M, Shockley FW, Giorgi A, Lord NP, et al. Phylogeny and classification of Cucujoidea and the recognition of a new superfamily Coccinelloidea (Coleoptera: Cucujiformia). Syst Entomol. 2015;40:745–78.

Robertson JA, Whiting MF, McHugh JV. Searching for natural lineages within the Cerylonid series (Coleoptera: Cucujoidea). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;46:193–205.

Sasaji H. In: Paper on Entomology presented to Prof. Takehiko Nakane in Commemoration of his Retirement. In: Systematic position of the genus Eidoreus sharp (Coleoptera: Clavicornia). Tokyo: Jpn Soc Coleopterol; 1986. p. 229–35.

Sasaji H. On the higher classification of the Endomychidae and their relative families (Coleoptera). Entomol J Fukui. 1987;1:44–51.

Mckenna DD, Wild AL, Kanda K, Bellamy CL, Beutel RG, Caterino MS, et al. The beetle tree of life reveals that Coleoptera survived end of Permian mass extinction to diversify during the cretaceous terrestrial revolution. Syst Entomol. 2015;40(4):835–80.

Toussaint EF, Seidel M, Arriaga–Varela E, Hájek J, Král D, Sekerka L, et al. The peril of dating beetles. Syst Entomol 2017;42(1):1–10.

Gordon RD. The Coccinellidae (Coleoptera) of America north of Mexico. J N Y Entomol Soc. 1985;93:654–78.

Kovář I. Phylogeny. In: Hodek I, Honěk A, editors. Ecology of Coccinellidae. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Pub. 1996. p. 19–31.

Vandenberg NJ. Family 93. Coccinellidae Latreille 1807. In: Arnett RH, Jr., Thomas MC, Skelley PE, Frank JH, editors. American Beetles. Volume 2. Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea. CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, FL; 2002. p. 19.

Sasaji H. Phylogeny of the family Coccinellidae (Coleoptera). Etizenia. 1968;35:1–37.

Sasaji H. Fauna Japonica. Coccinellidae (Insecta: Coleoptera). Academic Press of Japan, Keigaku Publishing Tokyo; 1971.

Ślipiński A. Australian ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): their biology and classification. Canberra: Australian Biological Resources Study; 2007.

Giorgi JA, Vandenberg NJ, McHugh JV, Forrester JA, Ślipiński SA, Miller KB, et al. The evolution of food preferences in Coccinellidae. Biol Control. 2009;51:215–31.

Magro A, Lecompte E, Magne F, Hemptinne J-L, Crouau-Roy B. Phylogeny of ladybirds (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): are the subfamilies monophyletic. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;54:833–48.

Aruggoda AGB, Shunxiang R, Baoli Q. Molecular phylogeny of ladybird beetles (Coccinellidae: Coleoptera) inferred from mitochondria 16S rDNA sequences. Trop Agric Res. 2010;21(2):209–17.

Seago AE, Giorgi JA, Li J, Ślipiński A. Phylogeny, classification and evolution of ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) based on simultaneous analysis of molecular and morphological data. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;60(1):137–51.

Ślipiński A, Coccinellidae Latreille TW. Handbook of Zoology, Vol. 2, Coleoptera. In: RAB L, Beutel RG, Lawrence JF, editors. , vol. 2010. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & co. KG; 1802. p. 454–72.

Hodek I. Biology of Coccinellidae. Prague, The Hague: Academia Publishing and W. Junk; 1973.

Majerus M. Ladybirds. The New Naturalist Library. London: Harper Collins Publishers. 357 pp; 1994.

Hodek I, Honěk A. Ecology of Coccinellidae. Series Entomologica, 54. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Pub. 1996.

Hodek I, van Emden HF, Honěk A. Ecology and behaviour of the ladybird beetles (Coccinellidae). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. 604 pp; 2012.

Pettersson J. Coccinellids and semiochemicals. In: Ecology and behaviour of the ladybird beetles (Coccinellidae). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2012; p. 444–64.

Brown PMJ, Thomas CE, Lombaert E, Jeffries DL, Estoup A, Lawson Handley L-J. The global spread of Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): distribution, dispersal and routes of invasion. BioControl. 2011;56:623–41.

Kovář I. Morphology and anatomy. In: Hodek I, Honěk A, editors. Ecology of Coccinellidae. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. p. 1–18.

Samways MJ, Osborn R, Saunders TL. Mandible form relative to the main food type in ladybirds (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Biocontrol Sci Tech. 1997;7:275–86.

Hodek I, Honěk A. Scale insects, mealybugs, whiteflies and psyllids (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha) as prey of ladybirds. Biol Control. 2009;51(2):232–43.

Kuznetsov VN. Lady beetles of the Russian far east. Center for Systematic Entomology Memoir. 1997;1:1–248.

Evans EW. Lady beetles as predators of insects other than Hemiptera. Biol Control. 2009;51(2):255–67.

Savoiskaya GI. Coccinellids of the Alma-Ata reserve. Trudy Alma Atinskogo Gosudarstvennogo Zapovednika. 1970;9:163–87.

Savoiskaya GI. Larvae of coccinellids (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae) of the fauna of the USSR. Leningrad: Zoologicheski Institut; 1983.

Sutherland AM, Parrella MP. Mycophagy in Coccinellidae: review and synthesis. Biol Control. 2009;51(2):284–93.

Regier JC, Shi D. Increased yield of PCR product from degenerate primers with nondegenerate, nonhomologous 5′ tails. BioTechniques. 2005;38:34–8.

Wild AL, Maddison DR. Evaluating nuclear protein-coding genes for phylogenetic utility in beetles. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;30;48(3):877–91.

Regier JC, Shultz JW, Ganley ARD, Hussey A, Shi D, Ball B, et al. Resolving arthropod phylogeny: exploring phylogenetic signal within 41 kb of protein-coding nuclear gene sequence. Syst Biol. 2008;57(6):920–38.

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–9.

Wernersson R. Virtual ribosome – a comprehensive DNA translation tool with support for integration of sequence feature annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:385–8.

Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–80.

Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, et al. Database resources of the National Center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(1):D38–51.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10.

Swofford DL. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods). Version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts; 2003.

Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3.

Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SYW, Guindon S. PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1695–701.

Zwickl DJ. Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence data sets under the maximum likelihood criterion. PhD thesis, The University of Texas; 2006. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/2666. Accessed 10 Jan 2014.

Sukumaran J, Holder MT. DendroPy: a python library for phylogenetic computing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):1569–71.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–5.

Ayres DL, Darling A, Zwickl DJ, Beerli P, Holder MT, Lewis PO, et al. BEAGLE: an application programming interface and high-performance computing library for statistical phylogenetics. Syst Biol. 2012;61:170–3.

Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Xie D, Drummond AJ. Tracer v1.6. Available from http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer; 2014.

Zwick A, Regier JC, Zwickl DJ. Resolving discrepancy between nucleotides and amino-acids in deep-level arthropod phylogenomics: differentiating serine codons in 21-amino-acid models. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e47450.

Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: A modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.7. 2008. http://mesquiteproject.org Accessed 5 Jun 2015.

Vandenberg NJ. Revision of the new world lady beetles of the genus Olla and description of a new allied genus (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1992;85:370–92.

Szawaryn K, Bocak L, Ślipiński A, Escalona HE, Tomaszewska W. Phylogeny and evolution of phytophagous ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae: Epilachnini), with recognition of new genera. Syst Entomol. 2015;40(3):547–69.

Iablokoff-Khnzorian SM. Les Coccinelles, Coleopteres-Coccinellidae, tribu Coccinellini des Regions Palearctique et Orientale. Paris: Societe Nouvelle des Editions Boubee; 1982.

Hemptinne JJ, Leclerq-Smekens M, Naisse J. Structure and function of the exocrine glands of the genitalia of females of the two-spot ladybird Adalia bipunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Belg J Zool. 1991;121:27–37.

Eisner T, Eisner M. Operation and defensive role of “gin traps” in a Coccinellid pupa (Cycloneda sanguinea). Psyche. 1992;99:225–73.

Sato S, Kushibuchi K, Yasuda H. Effect of reflex bleeding of a predatory ladybird beetle, Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), as a means of avoiding intraguild predation and its cost. Appl Entomol Zool. 2009;44(2):203–6.

Nedvěd O. Slunéčko východní (Harmonia axyridis) – pomocník v biologické ochraně nebo ohrožení biodiverzity? České Budějovice: Jihočeská univerzita; 2014.

Weber DC, Lundgren JG. Assessing the trophic ecology of the Coccinellidae: their roles as predators and as prey. Biol Control. 2009;51(2):199–214.

Roy HE, Adriaens T, Isaac N, Kenis M, Onkelinx T, San Martin G, et al. Invasive alien predator causes rapid declines of native European ladybirds. Divers Dist. 2012;18(7):717–25.

Hodek I. Food relationships. In: Hodek I, Honěk A, editors. Ecology of Coccinellidae. Dordrecht Boston London: Kluwer Academic Pub. 1996.

Biddinger DJ, Weber DC, Hull LA. Coccinellidae as predators of mites: Stethorini in biological control. Biol Control. 2009;51(2):268–83.

Ricci C. Sulla constituzione e funzione delle mandible delle larvae di Tytthaspis sedecimpunctata (L.) e Tytthaspis trilineata (Weise). Frustula Entomol. 1982;3:205–12.

Dejean A, Orivel J, Gibernau M. Specialized predation on plataspid heteropterans in a coccinellid beetle: adaptive behavior and responses of prey attended or not by ants. Behav Ecol. 2002;13:154–9.

Poorani J, Ślipiński A, Booth R. A revision of the genus Synona pope (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae, Coccinellini). Ann Zool. 2008;58(3):350–62.

Iwata K. On the biology of two large lady-birds in Japan. Trans Kansai Entomol Soc. 1932;3:13–26.

Bashford R. Predation by ladybird beetles (coccinellids) on immature stages of the eucalyptus leaf beetle Chrysoparta bimaculata (Olivier). Tasforest. 1999;11:77–86.

Whitehead DR, Duffield RM. An unusual specialized predator prey association (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae, Chrysomelidae): failure of a chemical defense and possible practical application. Coleopt Bull. 1982;36:96–7.

Pope RD. A revision of the Australian Coccinellidae (Coleoptera). Part 1. Subfamily Coccinellinae. Invertebr Syst. 1989;2[1988]:633–735.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. Vogler (Imperial College London and Natural History Museum, London) and two anonymous reviewers for their input. Thanks to C. Lemann (ANIC-CSIRO), L. Ashman (Australian National University), S. Pinzon-Navarro, O. Hlinka (CSIRO) and D. McKenna (University of Memphis) for technical help; L. Bocak, M. Bocakova, J. McHugh, K. Miller, M.A. Ivie, Y. Lee, N. Lord, J. Robertson, H. Yoshitomi and M. Whiting for providing specimens. Thanks to L. Borowiec, G. Gonzales, K. Makarov, B. Katayev, P. Zborowski, M. Yeo, J. Devalez, A. Bonnitcha, G. San Martin, N. Monaghan, M. Gulyaev, B. Marlin, J. Jeffery, R. Ware and S. Axford for permission to use their photographs or illustrations.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the Polish National Science Center (Narodowe Centrum Nauki), No. 2012/07/B/NZ8/02815 to W. Tomaszewska and A. Ślipiński; grant GA JU 152/2016/P by University of South Bohemia to O. Nedvěd; Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship to H. Escalona; National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grants No. 31572052 to H. Pang and No. 31501884 to X. Wang and National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program), Grant No. 2013CB127605 to H. Li and H. Pang.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within its additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AŚ, WT, HP, JL and HE conceived and designed the project. AŚ, JL, XW, DH and HE carried out field work or laboratory work or both: sorting and identifying samples, DNA extraction, PCR, sample preparation for sequencing, PCR protocols, generated DNA consensus sequence, multiple segment alignment and phylogenetic analysis. O. Nedvěd contributed with biological information. AZ and HSL conducted phylogenetic analyses. AŚ, WT and HE designed and carried out the morphological character reconstruction. AŚ and HE designed the main plates. AŚ, WT, HE and AZ wrote the manuscript with contributions from LSJ, O. Niehuis and BM. All authors approved its final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S3.

Character states of six discrete morphological and of one behavioural character. (DOCX 29 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Primers used for PCR amplification of the genes. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 3: Supermatrix S1.

The nucleotide multiple sequence alignment (MSA), used for the phylogenetic analysis, its partitions, nucleotide composition information and percentage of gaps and ambiguities per taxa. It contains 52 taxa identified by the species name, their voucher number and the gene fragments: WGL, TOPO, COI, CADXM and CADMC. (NEX 171 kb)

Additional file 4: Figs. S1a–e.

The best RAxML ML trees with bootstrap values from 100 rapid bootstrap pseudo-replicates for the four fragment MSA that lack WGL (Fig. S1a), TOPO (Fig. S1b), COI (Fig. S1c), CADXM (Fig. S1d) and CADMC (Fig. S1e). (PDF 5145 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S2.

The best (BIC) multiple sequence alignment partitioning scheme with corresponding substitution models generated with PartitionFinder (version 1.1.1; [41]). (TXT 2 kb)

Additional file 6: Fig. S4.

The best GARLI ML tree for the non-degenerated five-fragment MSA set with bootstrap support values (equivalent to Fig. 3 without Posterior Probabilities). (PDF 127 kb)

Additional file 7: Fig. S2.

The resulting tree of the MrBayes Bayesian analysis with posterior probabilities. (PDF 132 kb)

Additional file 8: Fig. S3.

The best RAxML ML tree with bootstrap values for the fully degenerated five-fragment MSA. (PDF 131 kb)

Additional file 9: Table S4.

Specimens used in this study with voucher identification (Australian National Insect Collection), data, and corresponding GenBank accession numbers. (XLS 35 kb)

Additional file 10: Fig. S5.

Ancestral state reconstruction based on parsimony (A) and maximum likelihood (B) for female colleterial glands in Coccinellidae. The ancestral states are present (blue) and absent (green). The topology is derived from the ML tree in Fig. 3. (TIFF 39987 kb)

Additional file 11: Fig. S6.

Ancestral state reconstruction based on parsimony (A) and maximum likelihood (B) for pupal gin traps in Coccinellidae. The ancestral states are present (green), absent (blue), unknown (shadowed) and uncertain (grey). The topology is derived from the ML tree in Fig. 3. (TIFF 53439 kb)

Additional file 12: Fig. S7.

Ancestral state reconstruction based on parsimony (A) and maximum likelihood (B) for larval dorsal glands in Coccinellidae. The ancestral states are present (blue), absent (green), unknown (shadowed) and uncertain (grey). The topology is derived from the ML tree in Fig. 3. (TIFF 60213 kb)

Additional file 13: Fig. S8.

Ancestral state reconstruction based on parsimony (A) and maximum likelihood (B) for larval waxes in Coccinellidae. The ancestral states are present (blue), absent (green), unknown (shadowed) and uncertain (grey). The topology is derived from the ML tree in Fig. 3. (TIFF 41014 kb)

Additional file 14: Fig. S9.

Ancestral state reconstruction based on parsimony (A) and maximum likelihood (B) for presence of dorsal pubescence in Coccinellidae. The ancestral states are present (blue) and absent (green). The topology is derived from the ML tree in Fig. 3. (TIFF 59853 kb)

Additional file 15: Fig. S10.

Ancestral state reconstruction based on parsimony (A) and maximum likelihood (B) for mandible type in Coccinellidae. The ancestral states are separated on fungivorous (light blue), mildew (purple), carnivorous1 (red), microphagous (yellow), phytophagous (green), carnivorous2 (black). The topology is derived from the ML tree in Fig. 3. (TIFF 60492 kb)

Additional file 16: Fig. S11.

Ancestral state reconstruction based on parsimony (A) and maximum likelihood (B) for food preferences in Coccinellidae. The ancestral states are separated on scales (purple), aphids (navy blue), herbivore (blue), mildew (light green), fungi (dark green), mixed (light blue), heteropterans (yellow), psyllids (orange), beetles (red), whiteflies (black), unknown (shadowed), uncertain (grey). The topology is derived from the ML tree in Fig. 3. (TIFF 58415 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Escalona, H.E., Zwick, A., Li, HS. et al. Molecular phylogeny reveals food plasticity in the evolution of true ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae: Coccinellini). BMC Evol Biol 17, 151 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-1002-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-017-1002-3