Abstract

Background

Organogenesis from tonsil-derived mesenchymal cells (TMSCs) has been reported, wherein tenogenic markers are expressed depending on the chemical stimulation during tenogenesis. However, there are insufficient studies on the mechanical strain stimulation for tenogenic cell differentiation of TMSCs, although these cells possess advantages as a cell source for generating tendinous tissue. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of mechanical strain and transforming growth factor-beta 3 (TGF-β3) on the tenogenic differentiation of TMSCs and evaluate the expression of tendon-related genes and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as collagen.

Results

mRNA expression of tenogenic genes was significantly higher when the mechanical strain was applied than under static conditions. Moreover, mRNA expression of tenogenic genes was significantly higher with TGF-β3 treatment than without. mRNA expression of osteogenic and chondrogenic genes was not significantly different among different mechanical strain intensities. In cells without TGF-β3 treatment, double-stranded DNA concentration decreased, while the amount of normalized collagen increased as the intensity of mechanical strain increased.

Conclusions

Mechanical strain and TGF-β3 have significant effects on TMSC differentiation into tenocytes. Mechanical strain stimulates the differentiation of TMSCs, particularly into tenocytes, and cell differentiation, rather than proliferation. However, a combination of these two did not have a synergistic effect on differentiation. In other words, mechanical loading did not stimulate the differentiation of TMSCs with TGF-β3 supplementation. The effect of mechanical loading with TGF-β3 treatment on TMSC differentiation can be manipulated according to the differentiation stage of TMSCs. Moreover, TMSCs have the potential to be used for cell banking, and compared to other mesenchymal stem cells, they can be procured from patients via less invasive procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tendinopathy is a chronic condition that hinders normal movement and causes inconvenience in daily life [1]. Upon injury of the tendon, a full return to its original state in terms of its structure and strength is often not achieved despite tendon repair surgery [2]. Acute and chronic tendon injuries can result in a decline in the quality of life. As society ages, the incidence of tendinopathy increases [3], and thus appropriate treatment for tendon injury should be developed.

Currently, direct repair or tendon transfer is predominantly used to treat tendinopathy [4, 5]. However, these remedies have some disadvantages as follows: the repair site consists of fibrous tissue rather than the original tissue post-surgery, which may cause fibrosis; the healing potency is low to eliminate scarring; and adhesion with other connective tissues is low [6]. To overcome these drawbacks, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been developed for use in tissue engineering. MSCs can be derived from many sites, such as adipose tissue, bone marrow, and cord blood [7]. Furthermore, MSCs are multipotent and can differentiate into tendons under appropriate culture conditions. Moreover, MSCs have shown promising potential for tendon repair in vitro and in animal studies [8, 9].

According to a previous study, adipose tissue-derived MSCs overexpressing scleraxis (SCX) have increased tenogenic gene expression and affect tendon cell differentiation [10]. Furthermore, the uniaxial strain on MSCs from the bone marrow is positively correlated with tendon matrix generation [11]. MSCs can be tenogenic under mechanical strain conditions and chemical stimulation [12, 13]. However, these stem cell-harvesting procedures are invasive and harmful, and donor site morbidity and the derived yield from single cells are limited [14]. Tonsil-derived mesenchymal cells (TMSCs) are considered waste tissues from tonsillectomy, although tissue banking is possible [15]. Organogenesis from TMSCs has been reported, wherein tenogenic markers are expressed depending on the chemical stimulation during tenogenesis [16]. However, there are insufficient studies on mechanical strain stimulation for tenogenic cell differentiation of TMSCs, although these cells possess advantages as a source for generating tendinous tissue.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of mechanical strain and transforming growth factor-beta 3 (TGF-β3) on the tenogenic differentiation of TMSCs and evaluate the expression of tendon-related genes and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as collagen. It was hypothesized that mechanical strain and TGF-β3 induced tendon-related gene expression and increased ECM components.

Results

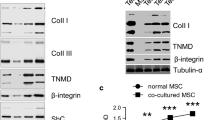

When TMSCs were treated with TGF-β3 without mechanical stimulation, the mRNA expression of tenomodulin (TNMD) was increased on day 3 compared to that in the untreated group (p = 0.012; Fig.1B). Especially, in the TGF-β3 group, the mRNA expression levels of TNMD (p = 0.033) and tenascin-C (TNC) (p = 0.054; Fig.1D) on day 14 were significantly higher than those of the TGF-β3 untreated group. However, TGF-β3 decreased the mRNA expression of SCX (p = 0.001; Fig.1A) and collagen type 1 (COL1) (p < 0.001; Fig.2A) on day 14 as well as that of COL3 on days 7 and 14 (p < 0.001; Fig.2B). Moreover, the mRNA expression of decorin (DCN) in TMSCs was decreased significantly at all time points by TGF treatment (p = 0.023 on day 3 and p < 0.001 on other days; Fig.1C).

mRNA expression of tenogenic genes (A) scleraxis, (B) tenomodulin, (C) decorin, and (D) TNC was measured using qRT-PCR after 1, 3, 7, and 14 days under mechanical strain without or with 10 ng/ml TGF-β3. Data shown are mean fold static condition group ± SEM at each time point. Significant differences are represented as follows (p < 0.05): static control vs strain groups without TGF-β3(*), between all groups (**), and without vs with 10 ng/ml TGF-β3 under static control (#)

Mechanical strain stimulated the mRNA expression of tenogenic marker genes in TGF-β3-untreated TMSCs. The mRNA expression of SCX under 2% strain without TGF-β3 treatment was significantly lesser than that under static control before day 7 (p < 0.001), and the mRNA expression under 5% strain in the TGF-β3-untreated strain group was the highest on days 1 and 3 (p = 0.008 and p < 0.001, respectively; Fig.1A). In addition, the mRNA expression of TNMD was increased in the strain group without TGF-β3 compared to that observed under static control on day 1, regardless of the strain intensity (p < 0.05; Fig.1B). There was no statistically significant difference in the mRNA expression of DCN and TNC (Fig.1C and 1D). The mRNA expression of COL1 was decreased in the strain group without TGF-β3 compared to that observed under static control over the whole experimental period (p < 0.001; Fig.2A). COL3 expression was decreased in the 2% strain group on day 3(p = 0.043; Fig.2B), and there was no statistically significant difference in the COL1/3 ratio between the strain groups without TGF-β3 (Fig.2C).

In the TGF-β3-treated strain TMSC group, the mRNA expression of SCX, TNMD, and TNC was significantly increased compared to that in the group without TGF-β3 on day 14 (p < 0.05), regardless of the strain intensity, but there was no synergistic effect between TGF-β3 and mechanical stimulation. Further, the mRNA expression of DCN was not further reduced by simultaneous treatment with TGF-β3 and mechanical stimulation (Fig. 1). The same results were obtained for the mRNA expression of COL1 and COL3 (Fig.2).

Mechanical stimulation had no effect on the mRNA expression of osteogenic and chondrogenic marker genes in TMSCs, except for runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), at day 14, and there was no change in the expression even under co-treatment with TGF-β3 (Fig. 3).

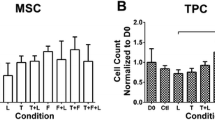

To confirm the effect of mechanical stimulation and TGF-β3 on TMSC proliferation, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) concentration was measured. dsDNA contents were inversely proportional to the intensity of mechanical stimulation in TMSCs. As the intensity of mechanical strain increased, dsDNA concentration decreased, and the total amount of dsDNA increased by TGF-β3 was also decreased by mechanical stimulation (p < 0.001; Fig.4A). The total amount of collagen proteins normalized by dsDNA content increased as the intensity of mechanical stimulation without TGF-β3 increased (p = 0.05 on day 7 and p < 0.001 on day 14, respectively), but there was no change under simultaneous treatment with TGF-β3 and mechanical stimulation (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

This study aimed to verify the ability of TGF-β3 and mechanical strain to stimulate the differentiation of TMSCs into tenocytes. We hypothesized that TGF-β3 and mechanical strain induce higher expression of tenocyte-related genes and collagen as end products. TGF-β3 and mechanical strain stimulated TMSC differentiation into tenocytes, although the combination of the two did not induce significantly higher TMSC differentiation.

TMSCs have some advantages over MSCs obtained from other sources. TMSCs are waste tissues from tonsillectomies; thus, they can be obtained via less invasive procedures, as additional surgery is not necessary [15]. Moreover, TMSCs can differentiate more stably than other MSCs, making them suitable for cell banking [17]. Therefore, TMSCs can be easily applied to autografts or allografts [18]. TMSCs have the potential to differentiate into a wide range of tissues. According to previous studies, TMSCs can be osteogenic, adipogenic, chondrogenic, myogenic, and tenogenic [15]. Additionally, TMSCs can be applied in the field of tissue engineering, as the control of the inter- and extracellular environments is possible.

We previously reported that a low concentration of TGF-β3 can induce tenogenic differentiation of TMSCs and increase the expression of SCX, TNMD, and TNC [16]. Similar results were obtained in this study when comparing the group treated with and without TGF-β3 in the static condition. However, in this study, an increase in the expression of SCX mRNA could not be observed when only TGF-β3 was used to treat TMSCs. Given that the protocol for TMSC stimulation using TGF-β3 was the same for this study and the previous one [16], we thought that the variations might have resulted from the differences in MSC sources. Regarding the expression of SCX, we believe that additional experiments will be required.

We measured the simultaneous effect of TGF-β3 and mechanical strain on TMSCs differentiation into tenocytes. In previous studies, TMSCs were used for chondrogenesis and adipogenesis using a modified 3D scaffold [19,20,21]. Park et al. reported that a 2D/3D hybrid cell culture system with TGF-β3 increases the expression of chondrogenic genes, such as SRY-Box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), COL II, COL II A1, and COL VII. Additionally, Patel et al. reported that a composite system of graphene oxide/polypeptide thermogel stimulates the expression of adipogenic genes, such as PPAR-γ, CEBP-α, LPL, AP2, ELOVL3, and HSL. However, there are insufficient studies regarding the tenogenic expression of TMSCs upon mechanical strain and TGF-β3 treatment, although Yu et al. reported that TGF-β3 induces tenogenesis of TMSCs.

As shown in Fig. 1, the mRNA expression of tenogenic genes, such as SCX, was significantly higher when the mechanical strain was applied than under static conditions. SCX is a transcription factor that leads to tenocyte differentiation and suppresses non-tenogenic capacity [22]. These results are similar to those of previous studies in that mechanical strain stimulates the differentiation of MSCs into tenocytes. As shown in Fig. 3, the mRNA expression levels of osteogenic and chondrogenic genes were similar among the static control, 2, and 5% groups. Similarly, Zhang et al. reported that the expression of non-tenocyte-related genes was not significantly altered when mechanical loading was applied to tenocytes [23]. Thus, we believe that mechanical strain can stimulate the differentiation of TMSCs, particularly to tenocytes.

In cells without TGF-β3, dsDNA concentration decreased, while the amount of normalized collagen increased as the intensity of mechanical strain increased. The concentration of dsDNA indicates the quantity of cell proliferation, whereas the amount of collagen as an end product indicates the extent of cell differentiation [24, 25]. The extent of cell proliferation and differentiation is inversely proportional [26]. Therefore, mechanical strain without TGF-β3 stimulates cell differentiation rather than proliferation.

Even though SCX was increased with loading and TGF-β3 combinations at days 7 and 14, the two treatments did not have a significant synergistic effect on the expression of other genes. For example, in cells treated with TGF-β3, the mRNA expression level of COL1, COL3, and COL1/3 among mechanical strain groups except COL3 at day1 had no significant difference. Moreover, under TGF-β3 treatment, mRNA expression was lesser with mechanical strain than without mechanical strain for TNMD at day 14, TNC at day 14, and COL3 at day 1. The mRNA expression of TNC at day 14 and COL3 at day 1 decreased when mechanical strain was applied with TGF-β3 treatment, and the mRNA expression of TNMD at day 1 and DCN without TGF-β3 treatment was higher than that obtained under the combination of TGF-β3 with mechanical strain. Furthermore, in the combination case, the concentration of collagen as an end-product did not significantly change. Although TGF-β3 stimulates TMSC differentiation into tenocytes, the combination of TGF-β3 and mechanical strain does not appear to significantly increase the mRNA expression of tendon-related genes. This result concurs with those of previous studies, which showed that mechanical loading inhibits the differentiation of MSCs with TGF-β3 supplementation [27]. Thorpe et al. reported that continuous dynamic compression from 0 to 42 days in the presence of TGF-β3 inhibits chondrogenesis, whereas delayed dynamic compression after TGF-β3 treatment from 0 to 21 days stimulates chondrogenesis [28]. Therefore, the effect of mechanical loading on MSC differentiation can be manipulated according to the MSC stage.

Furthermore, previous studies have shown that mechanical strain activates the TGF-β3 pathway, which stimulates TMSC differentiation into tenocytes [29]. In this study, TGF-β3 and mechanical strain were treated from the outside of the cell rather than measuring the amount of TGF-β3 expression inside the cell. Hence, this study offers a unique perspective in that the combination of TGF-β3 and mechanical strain did not significantly affect TMSC differentiation. However, the mRNA expression of tenocyte-related genes increased in cells treated with TGF-β3 compared to that in those lacking TGF-β3 treatment. Hence, this study had similar results to previous studies in that TGF-β3 stimulated the differentiation of TMSCs into tenocytes.

This study had some limitations. First, only TGF-β3 was used as a chemical stimulant for differentiation. Other chemicals, such as TGF-β1 or vascular endothelial growth factor, induce TMSC differentiation as well. A combination of TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 treatment can stimulate TMSC differentiation into tenocytes [30]. Second, the effect of TGF-β3 and mechanical strain was only measured for 7 days. Long-term measurements are required to investigate the lasting effect of TGF-β3 and mechanical strain and any possible changes that could occur after a longer duration. Lastly, an immunocytochemistry assay was not conducted. Through immunocytochemistry, the presence of tenogenic proteins as a result of TMSC differentiation was verified [31]. However, in this study, only collagen was measured as the end-product.

Conclusions

TGF-β3 and mechanical strain stimulate the differentiation of TMSCs, although a combination of the two does not have a significant synergistic effect. Overall, TMSCs have the potential to be used for cell banking, and compared to other MSCs, they can be procured from patients via less invasive procedures. Moreover, TMSCs can differentiate into many types of tissues; thus, they can be applied in the field of tissue engineering to remedy tendon-related diseases without surgery.

Methods

Isolation and culture of TMSCs

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. After tonsillectomy, discarded tonsils were obtained from six patients aged 6–8 years and sectioned into two samples per patient. The tonsil tissues were minced and digested in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) with 0.075% collagenase type I at 37 °C for 30 min. After filtration through a 100 μm cell strainer, mononuclear cells were obtained from the digested tonsil tissues. The isolated cells were seeded and incubated at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 in low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Hyclone, UT, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Corning, VA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) in a 5% CO2 incubator with humidified air at 37 °C. After 48 h, non-adherent cells were removed, and adherent TMSCs were cultured. We verified the surface markers of MSCs through fluorescence-activated cell sorting using the BD Stemflow™ Human MSC Analysis Kit (BD Biosciences) to confirm the MSC lineage. All TMSCs showed high expression of CD73 (99.93% ± 0.025), CD90 (98.23 ± 1.215), and CD105 (99.08 ± 0.278) and low expression of CD11b, CD19, CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR (0.20 ± 0.041). In addition, the pluripotency of TMSCs was verified using semi-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of differentiation marker genes and histological staining for terminal differentiation. TMSCs were harvested for further use between passages 3 and 8.

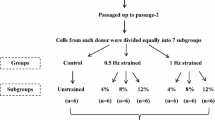

TGF-β3 treatment and mechanical strain

TMSCs were subjected to two types of treatment: TGF-β3 and mechanical strain. TMSCs were cultured at 1 × 104 cells/cm2 in six-well UniFlex plates coated with COL1. TMSCs were incubated for 1, 3, 7, and 14 days in DMEM/low-glucose containing 10% FBS and 50 μg/mL L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), with 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 or mechanical strain (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). During harvesting, the medium was changed, and TGF-β3 was supplemented every 2–3 days. The mechanical strain was applied to TMSCs once for 1 h per day using a Flexcell FX-5000 Tension system (Flexcell®, Burlington, NC, USA). The cells were subdivided into three groups: Static, 2, and 5%. The mechanical strain was expressed as a sine wave with a frequency of 0.5. Each experiment was repeated twice per patient.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using the SensiFAST™ SYBR® Hi-ROX kit (Bioline, London, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA expression levels were estimated using the Green I dye. Each specific primer was designed using Nucleotide BLAST, and 18S ribosomal RNA was used as an internal control (Table 1).

DNA content assay

dsDNA concentration was measured on day 7 to assess cell proliferation under each condition and normalize collagen content as an end product using the Quant-iT™ PicoGreen®dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The fluorescence intensity of the samples was measured to assess dsDNA concentration, whereby cells were digested in 1.5 mL of 0.15 mg/mL papain extraction reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for 3 h at 65 °C and excited at 485 nm, and the emittance was measured at 538 nm.

Collagen assay

Collagen concentration was assessed on day 7 using the Sircol™ Collagen Assay Kit (Biocolor, Antrim, UK). For collagen isolation, 2 mL of 0.1 mg/mL pepsin in 0.5 M acetic acid was added to the cultivated media. Pepsin digestion was performed overnight at 4 °C with constant agitation of the medium. To concentrate the collagen sample, 100 μL of acid-neutralizing reagent was added to 1 mL of the samples and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. As a blank control, 100 μL of cold isolation and concentration reagent was added to all samples, incubated overnight at 4 °C, and centrifuged at 13,000×g for 10 min, after which the supernatant was discarded. One milliliter of Sircol dye reagent was added to the samples and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with constant agitation. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, the pellet of each sample was dissolved in 1 mL of alkali reagent, and the absorbance was measured at 550 nm.

Statistical analysis

mRNA expression data were normalized to 0% strain value without TGF-β3 for each time. To compare the tenogenic effect of TGF-β3 in TMSCs, the non-TGF-treated group and the treated group without mechanical stimulation were statistically analyzed with an independent sample t-test. Statistical analysis among each group on days 1, 3, 7, and 14 was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc test using SPSS Statistics (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A representative graph was constructed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Significant differences are represented as follows (p < 0.05): static control vs strain groups without TGF-β3(*), static control with TGF-β3 vs other groups (**), and without vs with 10 ng/ml TGF-β3 on static control (#).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Change history

28 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12860-022-00406-9

Abbreviations

- COL1:

-

Collagen type 1

- COL2:

-

Collagen type 2

- COL3:

-

Collagen type 3

- DCN:

-

Decorin

- dsDNA:

-

Double-stranded DNA

- DMEM-LG:

-

Low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- MSCs:

-

Mesenchymal stem cells

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RUNX2:

-

Runt-related transcription factor 2

- SCX:

-

Scleraxis

- SOX9:

-

SRY-Box transcription factor 9

- TGF-β3:

-

Transforming growth factor-beta 3

- TMSCs:

-

Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- TNC:

-

Tenascin-C

- TNMD:

-

Tenomodulin

References

Kaux JF, Forthomme B, Goff CL, Crielaard JM, Croisier JL. Current opinions on tendinopathy. J Sports Sci Med. 2011;10(2):238–53.

Sharma P, Maffulli N. Tendon injury and tendinopathy: healing and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(1):187–202.

Zhou B, Zhou Y, Tang K. An overview of structure, mechanical properties, and treatment for age-related tendinopathy. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(4):441–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0026-2.

Hahn F, Meyer P, Maiwald C, Zanetti M, Vienne P. Treatment of chronic achilles tendinopathy and ruptures with flexor hallucis tendon transfer: clinical outcome and MRI findings. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(8):794–802. https://doi.org/10.3113/FAI.2008.0794.

Deese JM, Gratto-Cox G, Clements FD, Brown K. Achilles allograft reconstruction for chronic achilles tendinopathy. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2015;24(1):75–8.

Khanna A, Friel M, Gougoulias N, Longo UG, Maffulli N. Prevention of adhesions in surgery of the flexor tendons of the hand: what is the evidence? Br Med Bull. 2009;90(1):85–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldp013.

Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, Kluter H, Bieback K. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells. 2006;24(5):1294–301. https://doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.2005-0342.

Lee JY, Zhou Z, Taub PJ, Ramcharan M, Li Y, Akinbiyi T, et al. BMP-12 treatment of adult mesenchymal stem cells in vitro augments tendon-like tissue formation and defect repair in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17531. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017531.

Harris MT, Butler DL, Boivin GP, Florer JB, Schantz EJ, Wenstrup RJ. Mesenchymal stem cells used for rabbit tendon repair can form ectopic bone and express alkaline phosphatase activity in constructs. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(5):998–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orthres.2004.02.012.

Raabe O, Shell K, Fietz D, Freitag C, Ohrndorf A, Christ HJ, et al. Tenogenic differentiation of equine adipose-tissue-derived stem cells under the influence of tensile strain, growth differentiation factors and various oxygen tensions. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;352(3):509–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-013-1574-1.

Song G, Luo Q, Xu B, Ju Y. Mechanical stretch-induced changes in cell morphology and mRNA expression of tendon/ligament-associated genes in rat bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biomech. 2010;7(3):165–74.

Wang W, Deng D, Li J, Liu W. Elongated cell morphology and uniaxial mechanical stretch contribute to physical attributes of niche environment for MSC tenogenic differentiation. Cell Biol Int. 2013;37(7):755–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbin.10094.

Gulati BR, Kumar R, Mohanty N, Kumar P, Somasundaram RK, Yadav PS. Bone morphogenetic protein-12 induces tenogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from equine amniotic fluid. Cells Tissues Organs. 2013;198(5):377–89. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358231.

Koga H, Engebretsen L, Brinchmann JE, Muneta T, Sekiya I. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for cartilage repair: a review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(11):1289–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-009-0782-4.

Oh SY, Choi YM, Kim HY, Park YS, Jung SC, Park JW, et al. Application of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells in tissue regeneration: concise review. Stem Cells. 2019;37(10):1252–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.3058.

Yu Y, Lee SY, Yang EJ, Kim HY, Jo I, Shin SJ. Expression of tenocyte lineage-related factors from tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;13(2):162–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13770-016-9134-x.

Ryu KH, Cho KA, Park HS, Kim JY, Woo SY, Jo I, et al. Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: evaluation of biologic, immunologic and genetic factors for successful banking. Cytotherapy. 2012;14(10):1193–202. https://doi.org/10.3109/14653249.2012.706708.

Choi JS, Lee BJ, Park HY, Song JS, Shin SC, Lee JC, et al. Effects of donor age, long-term passage culture, and cryopreservation on tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(1):85–99. https://doi.org/10.1159/000374055.

Koh RH, Jin Y, Kang BJ, Hwang NS. Chondrogenically primed tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in riboflavin-induced photocrosslinking collagen-hyaluronic acid hydrogel for meniscus tissue repairs. Acta Biomater. 2017;53:318–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.081.

Park J, Kim IY, Patel M, Moon HJ, Hwang SJ, Jeong B. 2D and 3D hybrid Systems for Enhancement of chondrogenic differentiation of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25(17):2573–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201500299.

Patel M, Moon HJ, Ko DY, Jeong B. Composite system of graphene oxide and polypeptide thermogel as an injectable 3D scaffold for adipogenic differentiation of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(8):5160–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b12324.

Li YH, Ramcharan M, Zhou ZP, Leong DJ, Akinbiyi T, Majeska RJ, et al. The role of Scleraxis in fate determination of mesenchymal stem cells for tenocyte differentiation. Sci Rep-Uk. 2015;5(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13149.

Zhang JY, Wang JHC. The effects of mechanical loading on tendons - an in vivo and in vitro model study. Plos One. 2013;8(8).

Jager M, Feser T, Denck H, Krauspe R. Proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells cultured onto three different polymers in vitro. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33(10):1319–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-005-5889-2.

Fan HB, Liu HF, Toh SL, Goh JCH. Enhanced differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells co-cultured with ligament fibroblasts on gelatin/silk fibroin hybrid scaffold. Biomaterials. 2008;29(8):1017–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.048.

Agathocleous M, Harris WA. Metabolism in physiological cell proliferation and differentiation. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23(10):484–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2013.05.004.

Lima EG, Bian L, Ng KW, Mauck RL, Byers BA, Tuan RS, et al. The beneficial effect of delayed compressive loading on tissue-engineered cartilage constructs cultured with TGF-beta 3. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15(9):1025–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.008.

Thorpe SD, Buckley CT, Vinardell T, O'Brien FJ, Campbell VA, Kelly DJ. The response of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to dynamic compression following TGF-beta 3 induced Chondrogenic differentiation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(9):2896–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-010-0059-6.

Nam HY, Pingguan-Murphy B, Abbas AA, Merican AM, Kamarul T. Uniaxial cyclic tensile stretching at 8% strain exclusively promotes Tenogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9723025.

Bottagisio M, Lopa S, Granata V, Talo G, Bazzocchi C, Moretti M, et al. Different combinations of growth factors for the tenogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in monolayer culture and in fibrin-based three-dimensional constructs. Differentiation. 2017;95:44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2017.03.001.

Kraus A, Woon C, Raghavan S, Megerle K, Pham H, Chang J. Co-culture of human adipose-derived stem cells with tenocytes increases proliferation and induces differentiation into a tenogenic lineage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):754e–66e.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2019R1A2C2010150) and was partly supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2016R1C1B2008557). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (JW, HK, SJS, TL, and SYL) made significant contributions to the study design. JW and HK are co-first authors. All authors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. All authors provided final approval for the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Medical Center (SEUMC201907007), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The reference list was corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wee, J., Kim, H., Shin, SJ. et al. Influence of mechanical and TGF-β3 stimulation on the tenogenic differentiation of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells. BMC Mol and Cell Biol 23, 3 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12860-021-00400-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12860-021-00400-7