Abstract

Background

The green microalga Dunaliella salina accumulates a high proportion of β-carotene during abiotic stress conditions. To better understand the intracellular flux distribution leading to carotenoid accumulation, this work aimed at reconstructing a carbon core metabolic network for D. salina CCAP 19/18 based on the recently published nuclear genome and its validation with experimental observations and literature data.

Results

The reconstruction resulted in a network model with 221 reactions and 212 metabolites within three compartments: cytosol, chloroplast and mitochondrion. The network was implemented in the MATLAB toolbox CellNetAnalyzer and checked for feasibility. Furthermore, a flux balance analysis was carried out for different light and nutrient uptake rates. The comparison of the experimental knowledge with the model prediction revealed that the results of the stoichiometric network analysis are plausible and in good agreement with the observed behavior. Accordingly, our model provides an excellent tool for investigating the carbon core metabolism of D. salina.

Conclusions

The reconstructed metabolic network of D. salina presented in this work is able to predict the biological behavior under light and nutrient stress and will lead to an improved process understanding for the optimized production of high-value products in microalgae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microalgae received increased attention over recent years due to their ability to produce high-value compounds such as polyunsaturated fatty acids and carotenoids [1–3]. Optimizing microalgal growth and product compositions in order to facilitate economically feasible mass production is still challenging. A better understanding of the complex algal metabolism is an important prerequisite overcoming this hurdle. In regards to algal metabolism, the halophilic unicellular green alga Dunaliella salina is an excellent model organism to investigate changes in metabolism [4] as the physiology of the switch from primary growth to secondary stress metabolism with glycerol and carotenoid accumulation is very well known [5–7]. In addition, D. salina remains one of the few microalgae currently being commercialized for β-carotene production on a large scale [8].

The construction of dynamic-kinetic growth models using ordinary differential equations (ODEs) is a well-established formalism in bioprocess engineering. These models allow for prediction of biomass growth, nutrient uptake and metabolite production and enable the identification of bottlenecks in the process setup for both lab-scale and large-scale outdoor cultivation systems [9–11]. Simplified growth models are robust and computationally inexpensive. However, they might be only valid for a certain range of environmental conditions, thus limiting predictive capabilities for extrapolation outside the experimental region [12].

It is known that metabolic processes are based on complex reaction pathways throughout different subcellular compartments and its integration into a metabolic model is a prerequisite to get insight into the formation and regulation of metabolites [13]. Several flux-balance models of different plant and algal species have already been published. These include models for higher plants Arabidopsis [14], barley [15], Brassica napus seeds [16] and green microalgae such as Chlamydomonas [17–21], Chlorella [22–26] and Ostreococcus [27].

Currently, the productivities of microalgae are still below their actual potential. However, metabolic network reconstructions are the basis for stoichiometric modeling efforts and they have the ability to provide theoretical maximal substrate and product yields as well as calculation of internal metabolic rates. Furthermore, they enable in silico identification of genetic intervention strategies that guarantee a specified product yield, e.g. by engineering of the carotenoid or lipid synthesis pathways [28]. Usually, methods such as flux balance analysis (FBA) are used to determine the steady-state flux distribution in a metabolic network under given input conditions by maximization of an objective function. Moreover, extensions for FBA methods such as dynamic flux balance analysis (DFBA) exist, accounting for unbalanced growth conditions and dynamic extracellular effects on intracellular metabolism [21, 29]. This enables exploration of metabolic flux distributions consistent with stoichiometric and thermodynamic constraints as well as constraints formulated according to experimental data [30].

Since D. salina is the richest known source of natural β-carotene, a metabolic network model is highly beneficial to fully exploit the biotechnological potential of this alga. So far, for D. salina some metabolic profiling information is available [31, 32], and the first growth models have recently been created [11, 33, 34]. In addition, the genome of D. salina has been released (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/DunsalCCAP1918/DunsalCCAP1918.info.html) [35]. However, the annotation of the nuclear genome is challenging since it contains a high number of long introns and extensive repeats, complicating proper gene model construction. Therefore, a genome scale metabolic reconstruction for the industrially relevant microalga D. salina is still missing. Based on the nuclear genome of strain CCAP19/18 [35], a manual reconstruction of a carbon-core metabolic network was performed. The aim of the reconstructed stoichiometric network is to describe the metabolic flux distribution leading to the accumulation of the major biomass constituents in D. salina under fluctuating light and nutrient conditions.

Results

Reconstruction of a stoichiometric network for the carbon-core metabolism

By linking the annotated genetic information from [35] with bioinformatic knowledge from databases (e.g. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), a stoichiometric network for the carbon-core metabolism with interfaces to the amino acid metabolism of D.salina CCAP19/18 that comprises 221 reactions and 213 metabolites in three different compartments (chloroplast, cytosol and mitochondrion) was reconstructed. A comprehensive list of reactions and compounds in the metabolic network can be found in the Additional file 1. All entries in the list of reactions carrying an EC number (Enzyme commission number) and KEGG ID are annotated enzymes of the D.salina genome. Although more extensive metabolic networks exist for a variety of unicellular algae [20, 36, 37], the purpose of our work was to create the first reduced network that would still be capable of predicting biomass composition and productivities.

Figure 1, 2 and 3 show the network maps for the cytosol, the chloroplast and the mitochondrion respectively. To create the metabolic map with subcellular localization of enzymes, the prediction program PredAlgo was used. The prediction tool had been developed and designed to determine the subcellular localization of nuclear-encoded enzymes in C. reinhardtii [38]. Consequently, PredAlgo distinguishes between the following three compartments: the mitochondrion, the chloroplast, and the cytosol. The study of [38] showed that the application of PredAlgo led to an improved discrimination between plastidal and mitochondrial-localized proteins. As stated by its authors, PredAlgo works most accurately for the genus of Chlamydomonas and related green algal species (Chlorophyta).

Network map of carbon core metabolism in the cytosol and mitochondrion. For reasons of simplicity linear reactions were merged. The arrows display the direction and reversibility of the reactions. The blue font color refers to metabolites modeled as biomass compounds and the red font color refers to key reaction components such as energy and reduction equivalents

Network map of carbon core metabolism in the chloroplast. For reasons of simplicity linear reactions were merged. The arrows indicate the direction and reversibility of the reactions. The gray boxes indicate shuttling of metabolites between the considered compartments. The blue font color refers to metabolites modeled as biomass compounds and the red font color refers to key reaction components such as energy and reduction equivalents

Network map of the fatty acid and nucleic acid metabolism. The arrows indicate the direction and reversibility of the reactions. For reasons of simplicity linear reactions were merged. The gray boxes indicate shuttling of metabolites between the considered compartments. The blue font color refers to metabolites modeled as biomass compounds and the red font color refers to key reaction components such as energy and reduction equivalents

Algae of the genus Dunaliella and Chlamydomonas are closely related, because they both belong to the order of Volvocales [39], a comparison of annotated enzymes for the calvin cycle, the carbon-core metabolism and the isoprenoid biosynthesis of D.salina and C. reinhardtii showed a high degree of similarity [40]. In addition, there is a broad consensus that the carbon core metabolisms of green microalgae are conserved along several lineages since almost 90% of the functional annotated proteins of C. reinhardtii and of other microalgal proteins are homologs of Arabidopsis thaliana proteins [41]. For instance, similar to C. reinhardtii, the enzyme triose-phosphate isomerase (EC 5.3.1.1) is only present as one gene within the genome of D. salina. PredAlgo predicted a chloroplast localization, thus confirming the expected localization with the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle for carbon acquisition in the plastid of photosynthetic organisms. Moreover, multiple green algal species (Chlorophyta) share the presence of a glycolytic enolase (EC 4.2.1.11) with cytosolic localization rather than a plastid-localized enolase enzyme [42].

A major difference between the model alga C. reinhardtii and D.salina is the adaptation of D.salina to life under high salinities, whereas C. reinhardtii exclusively lives in soil and freshwater. Therefore, metabolism of D.salina was expected to reveal not only similarities, but also differences in subcellular localization of some of the annotated enzymes. For example, the enzyme the carbonic anhydrase (CA, EC 4.2.1.1) was included in the network to ensure carbon acquisition under high salt conditions. The genome of C. reinhardtii contains three α-type, six β-type and three γ-type CAs [43]. In contrast to freshwater species, [44] identified five α-type CAs and three γ-type CAs, but no β-type CAs in D. salina CCAP19/18. The newly identified α-type CA (DsCA2b) is suggested to improve CO2 assimilation under hypersaline conditions [44]. Based on results of [45], a plasma membrane localization acting on the extracellular side was assumed. Although a variety of genes code for different classes of carbonic anhydrases [44], we only considered the extracellular version in our model, because it is specific to Dunaliella.

In contrast, multiple green algal species (Chlorophyta) share the presence of a glycolytic enolase (EC 4.2.1.11) with cytosolic localization rather than a plastid-localized enolase enzyme [42]. The glycerol cycle is initiated by the formation of glycerol-3-phosphate from dihydroxyacetone-phosphate, either provided through glycolytic reactions in the cytosol or through the reductive pentose phosphate pathway in the chloroplast [46]. This reversible reaction is catalyzed by the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH), which exists as two different enzymes, Nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent enzyme (EC 1.1.1.8) with plastidal and cytosolic localization and the ubiquinone-dependent enzyme (EC 1.1.5.3) with cytosolic localization bound to the mitochondrial membrane. The following formation of glycerol from glycerol-3-phosphate was considered to be performed by the glycerol kinase (EC 2.7.1.30). The presented hypothesis of the glycerol cycle within the cytosol also includes the removal of glycerol by conversion to dihydroxyacetone via the dihydroxyacetone reductase (EC 1.1.1.156) and subsequent phosphorylation to dihydroxyacetone-phosphate by the glycerone kinase (EC 2.7.1.29), thus connecting the glycerol cycle back to the glycolysis. Another option for cells to dispose of glycerol may be through general alcohol dehydrogenases (EC 1.1.1.2/1.1.1.21). This is a novel finding, indicating that glycerol could be connected to the carbon core metabolism in more ways than previously proposed, possibly providing a second glycerol cycle in D. salina.

Regarding carotenoid biosynthesis, genes coding for all of the enzymes of the plastid localized isoprenoid biosynthesis referred to as the Methyl-Erythritol-Phosphate (MEP) pathway were identified [35]. In addition, genes for all prenyl transferases needed to synthesize phytoene were found in the genome and all genes coding for enzymes required for reactions leading to β-carotene were identified.

Flux balance analysis of low and high-light scenarios under nutrient repletion and depletion

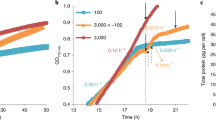

The reconstructed network was implemented in the MATLAB toolbox CellNetAnalyzer and checked for consistency and feasibility by using the function Check feasibility of flux scenario. Additionally, a FBA was carried out to analyze the plausibility of the flux distribution under varying light and nutrient conditions. The input fluxes for light (Ex01) and nutrients (Ex06) in the FBA scenarios were fixed according to experimentally obtained values for cultivations in a flat-plate bioreactor setup. For the nitrogen uptake rate, a maximal rate of 0.19 mmol/(g dw · h) for the nitrogen-replete scenarios and 0.001 mmol/(g dw · h) for the nitrogen-limited scenarios were calculated. Additionally, the maximal uptake rate for light (Ex01) was adapted to 800 mmol/(g dw · h) according to experimental values obtained in flat-plate bioreactor experiments under high light conditions [29]. The maintenance ATP requirement (Reaction R192) was calculated by dynamic modeling from chemostat experiments conducted in a laboratory flat-plate bioreactor and was fixed to 0.92 mmol/(g dw · h).

The results of the FBA for the defined scenarios (A-H) are listed in Tables 1 and 2. In the scenarios A and B, the nitrogen source represented by the metabolite nitrate (NO 3−) was set to the maximal reaction rate of 0.19 mmol/(g dw · h) to simulate autotrophic growth under nitrogen-replete conditions for low and high light conditions. For the scenarios C and D, the nitrate flux (Ex06) was set to 0.001 mmol/(g dw · h) to simulate autotrophic growth under nitrogen-limited conditions. The objective function was defined to maximize biomass growth under autotrophic conditions (represented by the biomass-forming reaction μ) and the internal fluxes were calculated.

The simulations for the scenarios E - G were carried out under the same nitrogen-replete and depleted conditions as A - D with the only difference that the maximization of the β-carotene flux (Car14) was added to the objective function to test whether the flux distribution enables a growth-coupled accumulation of secondary pigments. The objective function for these scenarios is defined as follows: maximization of biomass growth (reaction μ) and β-carotene production (reaction Car14).

The resulting growth rates μ for the biomass-maximizing scenarios A - D revealed a nitrogen limited growth regime. Under nitrogen-replete conditions, growth rates of 0.1287 h-1 and 0.7934 h-1 were predicted for the low light and high-light input flux (Ex01). The predicted growth rate under low-light conditions (3.09 d-1) is only slightly higher than previously published growth data for D. salina CCAP19/18 where a maximal growth rate of 1.71 d-1 was predicted by dynamic-kinetic modeling of batch cultivation data [47]. In the nutrient-depleted scenarios C and D, no biomass growth (μ=0.0007 h-1) occured neither under low light nor high light conditions.

In scenario A - D, biomass production occurred without any formation of β-carotene as a side product, meaning that the β-carotene flux Car14 is always 0 mmol/(g dw · h) (Table 1). Since the objective function did only include the biomass growth (μ) under nitrogen-replete conditions it is biologically plausible that β-carotene formation was suppressed in the flux scenarios A - D. As described by [6] and [11] oversaturating light conditions and nutrient repletion led only to moderate β-carotene accumulation, whereas oversaturating light combined with nutrient stress is the most potent inducer of secondary carotenoids in D. salina.

The tested scenarios E - H (Table 2) were similar to A - D despite the extension of the objective function to maximize the β-carotene flux (Car14). The same growth rates as in scenarios A - D were calculated (0.1287 h-1 and 0.7934 h-1 for nutrient-replete conditions and 0.0007 h-1 for nutrient-depleted conditions). However, the predicted β-carotene flux was different compared to scenarios A - D.

For the nutrient-replete scenarios E and F, the lowest β-carotene accumulation of 0.6962 mmol/(g dw · h) was predicted under low light conditions whereas a β-carotene flux (Car14) of 1.2972 mmol/(g dw · h) was predicted under high light conditions. Under nutrient-depleted conditions, the predicted β-carotene flux (Car14) was 0.7556 mmol/(g dw · h) under low light and 1.5359 mmol/(g dw · h) under high light conditions (Table 2).

Discussion

The reconstruction of a stoichiometric network for the carbon-core metabolism of D.salina CCAP19/18 was performed from annotated genetic information of with knowledge from bioinformatic databases such as KEGG. The size of the metabolic network for D.salina (221 reactions and 213 metabolites in three different compartments: chloroplast, cytosol and mitochondrion) is in the range of previously published reduced networks for green microalgae (e.g. for C.reinhardtii with 160 reactions, 164 metabolites in two compartments by [48] or with 259 reactions, 267 metabolites in 6 compartments by [49]).

With respect to the carotenoid synthesis, it was essential that all enzymes of the isoprenoid biosynthesis were identified, because under environmental stress cells of D. salina de-novo synthezise up to 10% of their dry weight as the isoprenoid molecule β-carotene [5]. Furthermore, the sequencing of various green algal species was an important prerequisite to study their different accumulation patterns of TAGs and carotenoids. [50] proposed that the pattern of carbon flow towards TAG or carotenoids is regulated by the NAD(P)H reduction state and the presence of bypass mechanisms such as pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). In the case of D. salina, the downregulation of PDH induced by high NAD(P)H levels under abiotic stress conditions favors β-carotene hyperaccumulation rather than massive TAG accumulation [50].

The results of the predicted β-carotene fluxes shown in Table 2 are supported by experimental observations for bioreactor cultivations of D. salina CCAP19/18 where low light and nutrient depletion led to the lowest β-carotene fraction of 30 mg/g dw followed by high light without nutrient stress with 43 mg/g dw. The highest experimentally observed β-carotene fraction was detected under high light coupled with nutrient stress, namely 80 mg/g dw [47]. This is in line with the biological function of β-carotene acting as a metabolic sink under conditions where growth is limited by excess light or nutrient stress [51]. The absence of biomass production in scenarios C-D and G-H is plausible, since nitrogen depletion leads to inhibition of protein biosynthesis which is a prerequiste for growth.

Conclusion

This work presents a metabolic network reconstruction of the carbon-core metabolism of D.salina CCAP19/18 based on the recently announced annotated genome [35]. The network comprises 221 reactions with 212 metabolites in three compartments (chloroplast, cytsol and mitochondrion). The network was implemented in the MATLAB toolbox CellNetAnalyzer and a flux balance analysis was carried out under various light and nutrient scenarios. The simulation results were compared with experimental observations of D.salina cultivated under nutrient repletion and depletion in a flat-plate photobioreactor [47]. All model predictions could be confirmed by experimental data and biological knowledge of D.salina metabolism. In conclusion, the metabolic network reconstruction is suitable to gain a better understanding of the flux distribution in the carbon core metabolism during carotenogenesis in D. salina. The ongoing experimental and computational advances will thereby accelerate the engineering of industrially valuable strains and provides the basis for effective biotechnology with photosynthetic microorganisms.

Methods

Reconstruction of the stoichiometric network

The stoichiometric model of D. salina CCAP19/18 carbon-core metabolism was reconstructed using a traditional (bottom-up) approach, which relied on manual reconstruction. It is based on the assignment of all annotated genes in the nuclear genome of D. salina CCAP19/18 to their proteins and the corresponding reactions supported by biological databases such as KEGG [35]. The complete reaction list is given in the Additional file 2. The graphical representation of the network was created in the vector graphics editor Inkscape (Version 0.92), which is based on [48].

Some metabolites in our stoichiometric network model may have one or more designations denoting their presence in different cellular compartments. Exchange reactions were added allowing the import and export between the considered cellular compartments.

Implementation and validation of the network

The complete set of reaction equations was implemented in the MATLAB toolbox CellNetAnalyzer and checked for feasibility [52]. Unless otherwise stated (e.g. for the nutrient uptake flux or the light flux) the lower and upper bounds for irreversible reactions were fixed to 0 - 100 mmol/(g dw · h), whereas reversible reaction bounds were fixed to -100 - 100 mmol/(g dw · h). The maximum flux boundaries of 100 mmol/(g dw · h) rely on biologically realistic values and are commonly used in FBA. For example, [53] categorized fluxes as low (<5 mmol/(g dw · h)), medium, (>5–10 mmol/(g dw · h)), and high (>10 mmol/(g dw · h)). The FBA was carried out for different objective functions as well as light and nutrient uptake rates by using the function Flux optimization. The network implementation and the values for the flux scenarios are provided in the Additional file 3.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Abbreviations

- CA:

-

Carbonic anhydrase

- CCAP:

-

Culture Collection of Algae and Protozoa

- DFBA:

-

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis

- EC:

-

Enzyme commission

- FBA:

-

Flux Balance Analysis

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes MEP: Methyl-Erythritol-Phosphate

- ODE:

-

Ordinary Differential Equation

References

Borowitzka MA. Commercial production of microalgae: ponds, tanks, tubes and fermenters. J Biotechnol. 1999; 70(1):313–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1656(99)00083-8. Biotechnological Aspects of Marine Sponges.

Adarme-Vega TC, Lim DKY, Timmins M, Vernen F, Li Y, Schenk PM. Microalgal biofactories: a promising approach towards sustainable omega-3 fatty acid production. Microb Cell Factories. 2012; 11(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-11-96.

Khan MI, Shin JH, Kim JD. The promising future of microalgae: current status, challenges, and optimization of a sustainable and renewable industry for biofuels, feed, and other products. Microb Cell Factories. 2018; 17(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-018-0879-x.

Ramos A. The unicellular green alga Dunaliella salina Teod. as a model for abiotic stress tolerance: Genetic advances and future perspectives. Algae. 2011; 26(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.4490/algae.2011.26.1.003.

Ben-Amotz A, Avron M. On the factors which determine massive β-carotene accumulation in the halotolerant alga Dunaliella bardawil. Plant Physiol. 1983; 72(3):593–7.

Lamers PP, van de Laak CCW, Kaasenbrood PS, Lorier J, Janssen M, De Vos RCH, Bino RJ, Wijffels RH. Carotenoid and fatty acid metabolism in light-stressed Dunaliella salina. Biotech Bioeng. 2010; 106(4):638–48.

Lamers PP, Janssen M, De Vos RCH, Bino RJ, Wijffels RH. Carotenoid and fatty acid metabolism in nitrogen-starved Dunaliella salina, a unicellular green microalga. J Biotechnol. 2012; 162(1):21–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.04.018.

Borowitzka M. A.High-value products from microalgae - their development and commercialisation. J Appl Phycol. 2013; 25(3):743–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-013-9983-9.

Packer A, Li Y, Andersen T, Hu Q, Kuang Y, Sommerfeld M. Growth and neutral lipid synthesis in green microalgae: A mathematical model. Bioresour Technol. 2011; 102(1):111–7.

Quinn J, de Winter L, Bradley T. Microalgae bulk growth model with application to industrial scale systems. Bioresour Technol. 2011; 102(8):5083–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.01.019.

Fachet M, Flassig RJ, Rihko-Struckmann L, Sundmacher K. A dynamic growth model of Dunaliella salina: Parameter identification and profile likelihood analysis. Bioresour Technol. 2014; 173C:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.08.124.

Mairet F, Bernard O, Masci P, Lacour T, Sciandra A. Modelling neutral lipid production by the microalga Isochrysis aff. galbana under nitrogen limitation. Bioresour Technol. 2011; 102(1):142–9.

Yu W-L, Ansari W, Schoepp NG, Hannon MJ, Mayfield SP, Burkart MD. Modifications of the metabolic pathways of lipid and triacylglycerol production in microalgae. Microb Cell Factories. 2011; 10(1):91. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-10-91.

de Oliveira Dal’Molin CG, Quek L-E, Palfreyman RW, Brumbley SM, Nielsen LK. AraGEM, a genome-scale reconstruction of the primary metabolic network in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010; 152(2):579–89. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.109.148817.

Grafahrend-Belau E, Junker A, Eschenröder A, Müller J, Schreiber F, Junker BH. Multiscale metabolic modeling: Dynamic flux balance analysis on a whole-plant scale. Plant Physiol. 2013; 163(2):637–47. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.224006.

Jordan H, Jörg S. Computational analysis of storage synthesis in developing Brassica napusj l. (oilseed rape) embryos: Flux variability analysis in relation to 13C metabolic flux analysis. Plant J. 2011; 67(3):513–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04611.x.

Boyle NR, Morgan JA. Flux balance analysis of primary metabolism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. BMC Syst Biol. 2009; 3:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-3-4.

Chang RL, Ghamsari L, Manichaikul A, Hom EF, Balaji S, Fu W, Shen Y, Hao T, Palsson BO, Salehi-Ashtiani K, Papin JA. Metabolic network reconstruction of Chlamydomonas offers insight into light-driven algal metabolism. Mol Syst Biol. 2011; 7:518.

Dal’Molin CG, Quek LE, Palfreyman RW, Nielsen LK. AlgaGEM - a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of algae based on the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii genome. BMC Genomics. 2011; 12(4):1–10.

Saheed I, Sascha S, Jacob V, de Lomana Adrian LG, Warren C, Price ND, Baliga NS. A refined genome-scale reconstruction of Chlamydomonas metabolism provides a platform for systems-level analyses. Plant J. 2015; 84(6):1239–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13059.

Mora Salguero DA, Fernández-Niño M, Serrano-Bermúdez LM, Páez Melo DO, Winck FV, Caldana C, González Barrios AF. Development of a Chlamydomonas reinhardtii metabolic network dynamic model to describe distinct phenotypes occurring at different CO2,) levels. PeerJ. 2018; 6(e5528):1–25. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5528.

Yang C, Hua Q, Shimizu K. Energetics and carbon metabolism during growth of microalgal cells under photoautotrophic, mixotrophic and cyclic light-autotrophic/dark-heterotrophic conditions. Biochem Eng J. 2000; 6(2):87–102.

Muthuraj M, Palabhanvi B, Misra S, Kumar V, Sivalingavasu K, Das D. Flux balance analysis of Chlorella sp. FC2 IITG under photoautotrophic and heterotrophic growth conditions. Photosynth Res. 2013; 118(1-2):167–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-013-9943-x.

Wu C, Xiong W, Dai J, Wu Q. Genome-based metabolic mapping and 13C flux analysis reveal systematic properties of an oleaginous microalga Chlorella protothecoides. Plant Physiol. 2015; 167(2):586–99. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.250688.

Zhu Y, Huang Y. Use of flux balance analysis to promote lipid productivity in Chlorella sorokiniana. J Appl Phycol. 2017; 29(2):889–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-016-0973-6.

Parichehreh R, Gheshlaghi R, Mahdavi MA, Elkamel A. Optimization of lipid production in chlorella vulgaris for biodiesel production using flux balance analysis. Biochem Eng J. 2019; 141:131–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2018.10.011.

Krumholz EW, Yang H, Weisenhorn P, Henry CS, Libourel IGL. Genome-wide metabolic network reconstruction of the picoalga Ostreococcus. J Exp Bot. 2012; 63(6):2353–62.

Gimpel JA, Henriquez V, Mayfield SP. In metabolic engineering of eukaryotic microalgae: Potential and challenges come with great diversity. Front Microbiol. 2015; 6:1376.

Flassig RJ, Fachet M, Höffner K, Barton PI, Sundmacher K. Dynamic flux balance modeling to increase the production of high-value compounds in green microalgae. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016; 9(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-016-0556-4.

Höffner K, Harwood SM, Barton PI. A reliable simulator for dynamic flux balance analysis. Biotech Bioeng. 2013; 110(3):792–802. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.24748.

Samburova V, Lemos MS, Hiibel S, Kent Hoekman S, Cushman JC, Zielinska B. Analysis of triacylglycerols and free fatty acids in algae using ultra-performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2013; 90(1):53–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-012-2138-3.

Lv H, Cui X, Wang S, Jia S. Metabolic profiling of Dunaliella salina shifting cultivation conditions to nitrogen deprivation. Metabolomics Open Access. 2016; 6(1). https://doi.org/10.4172/2153-0769.1000170.

Bechet Q, Moussion P, Bernard O. Calibration of a productivity model for the microalgae Dunaliella salina accounting for light and temperature. Algal Research. 2017; 21:156–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2016.11.001.

Bechet Q, Coulombier N, Vasseura C, Lasserre T, Le Dean L, Bernard O. Full-scale validation of an algal productivity model including nitrogen limitation. Algal Research. 2018; 31:377–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2018.02.010.

Polle JEW, Barry K, Cushman J, Schmutz J, Tran D, Hathwaik LT, Yim WC, Jenkins J, McKie-Krisberg Z, Prochnik S, Lindquist E, Dockter RB, Adam C, Molina H, Bunkenborg J, Jin E, Buchheim M, Magnuson J. Draft Nuclear Genome Sequence of the Halophilic and Beta-Carotene-Accumulating Green Alga Dunaliella salina Strain CCAP19/18. Genome Announc. 2017; 5(43).

Reijnders MJMF, van Heck RGA, Lam CMC, Scaife MA, Santos VAPMd, Smith AG, Schaap PJ. Green genes: Bioinformatics and systems-biology innovations drive algal biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2014; 32(12):617–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.10.003.

Loira N, Mendoza S, Paz Cortas M, Rojas N, Travisany D, Genova AD, Gajardo N, Ehrenfeld N, Maass A. Reconstruction of the microalga Nannochloropsis salina genome-scale metabolic model with applications to lipid production. BMC Syst Biol. 2017; 11(1):66.

Tardif M, Atteia A, Specht M, Cogne G, Rolland N, Brugiere S, Hippler M, Ferro M, Bruley C, Peltier G, Vallon O, Cournac L. PredAlgo: A new subcellular localization prediction tool dedicated to green algae. Mol Biol Evol. 2012; 29(12):3625–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss178.

Gonzalalez MA, Gomez PI, E. W. Polle J. In: Ben-Amotz A, Polle EWJ, Subba Rao DV, (eds).Taxonomy and Phylogeny of the Genus Dunaliella, 1st. Enfield: Science Publishers; 2009. Chap. 15-43.

Xenie J, Jean A. Central carbon metabolism and electron transport in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Metabolic constraints for carbon partitioning between oil and starch. Eukaryotic Cell. 2013; 12(6):776–93. https://doi.org/10.1128/EC.00318-12.

Reijnders MJMF, Carreres BM, Schaap PJ. Algal Omics: The functional annotation challenge. Curr Biotechnol. 2015; 4(4):457–63.

Polle JEW, Neofotis P, Huang A, Chang W, Sury K, Wiech EM. Carbon partitioning in green algae (Chlorophyta) and the enolase enzyme. Metabolites. 2017; 4(3):612–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo4030612.

Moroney J, Yunbing M, Frey WD, Fusilier KA, Pham TT, Simms T, Dimario RJ, Yang J, Mukherjee B. The carbonic anhydrase isoforms of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Intracellular location, expression, and physiological roles. Photosynth Res. 2011; 109:133–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-011-9635-3.

Jeon H, Jeong J, Baek K, McKie-Krisberg Z, Polle JEW, Jin E. Identification of the carbonic anhydrases from the unicellular green alga Dunaliella salina strain CCAP 19/18. Algal Res. 2016; 19:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2016.07.010.

Premkumar L, Bageshwar UK, Gokhman I, Zamir A, Sussman JL. An unusual halotolerant α-type carbonic anhydrase from the alga Dunaliella salina functionally expressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2003; 28(1):151–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1046-5928(02)00683-6.

Chitlaru E, Pick U. Regulation of glycerol synthesis in response to osmotic changes in Dunaliella. Plant Physiol. 1991; 96(1):50–60. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.96.1.50.

Fachet M, Flassig RJ, Rihko-Struckmann LK, Sundmacher K. Carotenoid production process using green microalgae of the Dunaliella genus: Model-based analysis of interspecies variability. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2017; 56(45):12888–98. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.7b01423.

Kliphuis A, Klok A, Martens D, Lamers P, Janssen M, Wijffels R. Metabolic modeling of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Energy requirements for photoautotrophic growth and maintenance. J Appl Phycol. 2011; 24(2):253–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-011-9674-3.

Manichaikul A, Ghamsari L, Hom EF, Lin C, Murray RR, Chang RL, Balaji S, Hao T, Shen Y, Chavali AK, Thiele I, Yang X, Fan C, Mello E, Hill DE, Vidal M, Salehi-Ashtiani K, Papin JA. Metabolic network analysis integrated with transcript verification for sequenced genomes. Nat Methods. 2009; 6(8):589–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1348.

McKie-Krisberg Z, Laurens L, Huang A, Polle JEW. Comparative energetics of carbon storage molecules in green algae. Algal Res. 2018; 31:326–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2018.01.018.

Rabbani S, Beyer P, Von Lintig J, Hugueney P, Kleinig H. Induced β-carotene synthesis driven by triacylglycerol deposition in the unicellular alga Dunaliella bardawil. Plant Physiol. 1998; 116(4):1239–48.

Klamt S, Saez-Rodriguez J, Gilles ED. Structural and functional analysis of cellular networks with CellNetAnalyzer. BMC Syst Biol. 2007; 1:2.

Chapman, Stephen & Lau, Caroline & Johnson, Giles & Schwartz, Jean-Marc. Flux balance analysis reveals acetate metabolism modulates cyclic electron flow and alternative glycolytic pathways in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.BMC Syst Biol. 2015; 6:474. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00474.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steffen Klamt for pointing out some inconsistencies in the FBA model. This manuscript contains experimental values and simulation results that has been incorporated in the following PhD thesis: Systematic Analysis of Carotenogenesis in Microalgae for Model-Based Process Design, M. Fachet, June 2017.

Funding

This research work was partly supported by the Center for Dynamic Systems (CDS) funded by the Federal State Saxony-Anhalt (Germany). The funding body played no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZMKK and JEWP provided the annotated genetic information for D. salina CCAP19/18. MF and CW reconstructed the stoichiometric network model, implemented it in CellNetAnalyzer and carried out the FBA. RJF, LRS and KS designed the research concept and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1

List of reactions, metabolites and biomass composition.

Additional file 2

SBML file.

Additional file 3

Flux values, constraints, gene-protein reaction associations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fachet, M., Witte, C., Flassig, R.J. et al. Reconstruction and analysis of a carbon-core metabolic network for Dunaliella salina. BMC Bioinformatics 21, 1 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-019-3325-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-019-3325-0