Abstract

Background

Nanoparticles play a crucial role in nanodiagnostics, radiation therapy of cancer, and they are now widely used to effectively deliver drugs to specific sites, targeting whole organs and down to single cells, in a controlled manner. Therapeutic efficiency of nanoparticles greatly depends on their clustering distribution inside cells. Our purpose is to find the cluster density using Smoluchowski’s coagulation equation with injections.

Results

We obtain an exact cluster density of nanoparticles as the steady-state solution of Smoluchowski’s equation describing clustering due to the fusion of endosomes. We also analyze the unsteady cluster distribution and compare it with the experimental data for time evolution of gold nanoparticle clusters in living cells.

Conclusions

We show the steady cluster density is in good agreement with experimental data on gold nanoparticle distribution inside endosomes. We find that for clusters containing between 1 and 20 nanoparticles, the exact cluster density provides a better description of the existing experimental data than the well-known approximate asymptotic power-law distribution \(x^{-3/2}\)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nanoparticles, particles smaller than 100 nm, have become increasingly important tools in modern medicine over the last few decades. Their applications vary from nanodiagnostics (Park et al. 2017) to radiation therapy of cancer (Hainfeld et al. 2004; Klapproth et al. 2021) and they are now widely used to effectively deliver drugs to specific sites, targeting whole organs and down to single cells, in a controlled manner (Ghosh et al. 2008; Mitchell et al. 2021). Nanoparticles play a crucial role in advancing gene therapy, capable of curing many disorders that can not be tackled by traditional medicine (Whitehead et al. 2009). In recent years, pH-sensitive nanoparticles and a virus-mimicking pH-responsive nanoparticles in endosomes have attracted much attention in the problem of targeted drug delivery (Zhou et al. 2011; Fedotov et al. 2022) and anti-tumor therapeutics delivery (Wannasarit et al. 2019; Braga et al. 2020; Figueroa et al. 2021; Ma et al. 2021; Lodhi et al. 2021). We should also mention the toxicity effects induced by nanoparticles. Cytotoxicity associated with them depends on their concentration, cluster distribution, the capacity for accumulation in cells and must be carefully balanced with the positive therapeutic effect (Elsaesser and Howard 2012; Yang et al. 2021; Sukhanova et al. 2018; Panov et al. 2020).

Therapeutic efficiency of nanoparticles greatly depends on their intracellular transport and distribution inside cells (Kong et al. 2017). For example, due to the short range of secondary electrons produced by interaction of the radiation field with gold nanoparticles (GNPs), radiation dose enhancement crucially depends on the location of GNPs within cells (Lin et al. 2015; Sung et al. 2017). Therefore, the knowledge of the intracellular GNP distribution is critical for improving GNP enhanced radiotherapy (Haume et al. 2016; Her et al. 2017; Peukert et al. 2018; Villagomez-Bernabe and Currell 2019; Villagomez-Bernabe et al. 2021). An added complexity is that this distribution of GNPs is not uniform (Sadauskas et al. 2009; Peckys and de Jonge 2011, 2014; Stefančíková et al. 2014) and transmission electron microscopy confirms that the clusters of GNPs are predominantly found inside endosomes (Liu et al. 2017). Initially, they appear within the cell as small clusters inside primary endocytic vesicles that deliver nanoparticles to early endosomes in the peripheral cytoplasm (Liu et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2016). Through the intracellular transport of early endosomes along microtubules, GNPs aggregate via endosome fusion and accumulate in late endosomes and lysosomes. These observations indicate that the cluster formation process is mediated by endosomal fusion rather than GNP self-aggregation.

While there have been various studies focusing on the distribution of nanoparticles within a local sub-cellular cluster (e.g., Liu et al. 2017), the view usually taken is that the material residing between the nanoparticles within each cluster does not constitute a biologically active target (Villagomez-Bernabe and Currell 2019). However, there are rare exceptions, for example, when the nanoparticles manage to penetrate into the nucleus (McCullogh et al. 2019). Except for these rare cases, analysis within the local effect model framework suggests that the specific placement of nanoparticles is not important in determining biological outcome for a wide range of distributions (Villagomez-Bernabe et al. 2021). However, the total loading of nanoparticles within each cluster and the cluster size are key parameters. To date there have been no reported studies about the nanoparticle loading, or equivalently, the steady-state density as a function of cluster size. In this work, we consider the clustering of nanoparticles inside endosomes by using the Smoluchowski’s coagulation equation with injections (Hayakawa 1987; Takayasu 1989; Cueille and Sire 1998). This equation was used by Foret et al. (2012) who studied the distributions of endocytosed low-density lipoprotein. They found an asymptotic (for large cluster size) steady-state density of endosomes within cells. This asymptotic steady-state density was found to decay, with increasing cluster size, as a power-law with an exponential cut-off. The purpose of this work is to find an exact density for steady-state cluster size distribution and compare it with the experimental data for all ranges of cluster distribution including the most important case of small cluster size. Note that recently a Smoluchowski-like equation has been applied to describe the stochastic fusion and fission events regulating endosome maturation (Castro et al. 2021).

Mathematical model and results

In this paper, we formulate the problem of clustering of nanoparticles in terms of Smoluchowski’s coagulation equation with injections and find the exact steady-state solution describing cluster size distribution.

Clustering of nanoparticles inside cells

Following receptor-mediated endocytosis, nanoparticles are trafficked along an endocytic pathway, which involves a dynamic network of vesicles. First, endocytosed nanoparticles enter a pool of early endosomes and then pass to the late endosomes and lysosomes. In our model, we assume that clustering of nanoparticles occurs as the result of fusion of endosomes during their intracellular transport along microtubules to the perinuclear region (Korabel et al. 2021). A schematic diagram is illustrated in Fig. 1. It is natural to describe the fusion process and clustering of nanoparticles in terms of the Smoluchowski’s coagulation equation. We assume that each endosome contains x nanoparticles (for example, GNPs) and for simplicity we consider x as a continuous variable. The primary quantity of interest is the structural density of endosomes per cell carrying x nanoparticles, n(x, t). The total number of nanoparticle-carrying endosomes in a cell can be found by integration: \(\lambda (t) = \int \nolimits _0^\infty n(x, t)\text{d}x\). The total number of nanoparticles inside a cell is given by \(N (t) = \int \nolimits _0^\infty xn(x, t)\text{d}x\). The evolution of n(x, t) is described by the Smoluchowski’s coagulation equation with injections (Foret et al. 2012):

where I(x) is the injection rate of new endosomes carrying x GNPs, \(\gamma (x)\) is the rate of exocytosis of endosomes. The first and second terms on the RHS of Eq. (1) describe the fusion of two endosomes with the rate K during which nanoparticles are shared. For example, when two endosomes carrying x and \(x^\prime\) nanoparticles are fused together with the rate \(K(x,x^\prime )\), they share their nanoparticles such that the newly formed endosome has \(x + x^\prime\) nanoparticles. Equation (1) should be supplemented with the initial density \(n(x,0)=n_0(x)\). Continuous and discrete Smoluchowski’s equations with injections have been studied extensively (Hayakawa 1987; Takayasu 1989; Cueille and Sire 1998) with the asymptotic and scaling solutions already found for several types of the kernel K. Of course, the number of nanoparticles x is not continuous. Considering x as a discrete variable, we arrive at the discrete Smoluchowski equation, which can be solved numerically (see, for example, Smith et al. 2018). However, the continuous variable x is more convenient from experimental point of view because x can represent brightness/hue values of the dark-field images of NP clusters (Wang et al. 2016). In the experiments, the number of NPs in the clusters is estimated by brightness values (see “Discussion” and experimental data on gold nanoparticle distribution inside endosomes Wang et al. 2016).

Schematic diagram of GNP endocytosis and clustering via endosome fusion. Endocytosed GNPs enter a pool of early endosomes and then pass to the late endosomes and lysosomes. We assume that clustering of nanoparticles occurs as the result of fusion of endosomes during their intracellular transport along microtubules

In Foret et al. (2012), the authors considered a constant fusion rate K, a constant rate \(\gamma\), and a source of cargo-loaded endosomes described by a source function

where \(J = \int _0^{\infty } x I(x) \text{d}x\) is the total flux. Under these conditions, an asymptotic stationary power-law solution was found for \(x>> x_0\): \(n_{\text{st}} \sim x^{-3/2}\) .

The aim of this paper is to find an exact steady-state solution for all cluster sizes: \(0<x<\infty\) under the same conditions. In what follows, we will show this exact steady-state solution provides a better description of existing experimental data than the asymptotic solution of Eq. (1). It is convenient to introduce the dimensionless time variable \(\tau\) and parameter \(\kappa\) :

Substituting Eq. (3) into the governing Eq. (1), we get

where

Equation (4) can be analyzed using the Laplace transform with respect to the dimensionless variable x

Equation (4) in the Laplace space reads as

The equation for the total number of GNP-carrying endosomes in a cell, \(\lambda (\tau ) = \int \nolimits _0^\infty n(x, \tau)\text{d}x\), can be easily obtained from Eq. (6) setting \(p=0\):

In the next section, we will use Eqs. (6) and (7) to find the exact analytical steady-state of nanoparticles cluster distribution.

Exact analytical solutions of the steady-state model

In this section, we find the exact stationary solution of Eq. (6) which allows us to validate the model using experimental distributions of GNP clusters at long times (Wang et al. 2016). As a first step let us find the stationary total number of GNP-carrying endosomes in a cell, \(\lambda _{\text{st}}\). Equating the left-hand side of Eq. (7) to zero, we come to the quadratic equation for \(\lambda _{\text{st}}\) whose solution reads:

Equating the right-hand side of Eq. (6) to zero and taking into account Eq. (8), we obtain a quadratic equation for \({\tilde{n}}_{\text{st}}\) whose convergent solution is given by

where \(a=\sqrt{2 Q x_0 +\kappa ^2}\).

In order to find the inverse Laplace transform of Eq. (9), it is convenient to multiply and divide its right-hand side by the conjugate expression \(a +\sqrt{a^2 -2 Q x_0/(1+x_0 p)}\). Omitting simple mathematical transformations, we get

where

Surprisingly, one can find the inverse Laplace transform to Eq. (10) using the tabulated formula [see expression 22.95 in Ditkin and Prudnikov (1965)]. So we obtain the exact analytical steady-state of NP’s cluster density

where \(I_0\) and \(I_1\) are the modified Bessel functions. An example of the steady-state function \(n_{\text{st}}(x)\) is shown in Figs. 2 and 3 for two sets of parameter values.

Steady-state structural density of nanoparticles in CL1-0 cells. The exact stationary structural density (Eq. 11, the solid curve) and the asymptotic steady-state structural density (Eq. 13, the dashed-dotted curve) calculated with parameters \(K= 10^{-4}\) s−1, \(\gamma =1.5\cdot 10^{-3}\) s−1, \(x_0=2\), \(J=10.5\) s−1. The inset shows comparison of the number of endosomes with clusters containing 4–6, 7–12 and more than 12 GNPs obtained using the exact density \(n_{\text{st}}(x)\) (Eq. 11) (red bars), asymptotic steady-state structural density (Eq. 13) (yellow bars) and the experimental data of Wang et al. (2016) (blue bars) (corresponding to number of spots after 8 h) for CL1-0 cells. The number of endosomes with clusters containing 4–6, 7–12 and more than 12 GNPs was calculated using the exact density \(n_{\text{st}}(x)\) (Eq. 11) as \(\sum _{i=4}^{6} n_{\text{st}}(i)\), \(\sum _{i=7}^{12}n_{\text{st}}(i)\) and \(\sum _{i=12}^{20}n_{\text{st}}(i)\), respectively. For asymptotic steady-state structural density (Eq. 13), the number of endosomes with clusters containing 4–6, 7–12 and more than 12 GNPs was calculated in the same way. Parameters were chosen such that the number of endosomes with more than 12 GNPs obtained with Eqs. (11) and (13) was similar

Steady-state structural density of nanoparticles in Beas-2B cells. The analytical stationary structural density (Eq. 11, the solid curve) and the asymptotic steady-state structural density (Eq. 13, the dashed-dotted curve) calculated with parameters \(K= 10^{-4}\) s−1, \(\gamma =1.5\cdot 10^{-3}\) s−1, \(x_0=2\), \(J=0.7\) s−1. The inset shows comparison of the number of endosomes with clusters containing 4–6 and 7–12 obtained using the exact density \(n_{\text{st}}(x)\) (Eq. 11) (red bars), asymptotic steady-state structural density (Eq. 13) (yellow bars) and the experimental data of Wang et al. (2016) (blue bars) (corresponding to number of spots after 8 h) for Beas-2B cells. The number of endosomes with clusters containing 4–6 and 7–12 GNPs was calculated using the exact density \(n_{\text{st}}(x)\) (Eq. 11) as \(\sum _{i=4}^{6} n_{\text{st}}(i)\) and \(\sum _{i=7}^{12}n_{\text{st}}(i)\). For asymptotic steady-state structural density (Eq. 13), the number of endosomes with clusters containing 4–6 and 7–12 GNPs was calculated in the same way

Discussion

Comparison with experimental distribution of GNPs

The cluster density Eq. (11) is in good agreement with experimental data on gold nanoparticle distribution inside endosomes (Wang et al. 2016). In what follows, we show that for clusters containing between 1 and 20 nanoparticles, distribution Eq. (11) provides a better description of the existing experimental data than the well-known approximate asymptotic power-law distribution \(x^{-3/2}\) (Foret et al. 2012).

Recently, Wang and colleagues (Wang et al. 2016) measured the intracellular distribution of GNPs clusters. In these experiments, 100 \(\upmu\)L of 50 nm-diameter gold nanospheres were injected into the micro-fluidic chip with cells and fresh medium were kept flow into the chamber to keep a fluidic environment. GNPs interacted with cells by adhering to cell membranes and adhered GNPs were then endocytosed into cells. By using the dark-field illumination, the individual GNPs were observed on the surface of cells as green sports. Subsequently, the number of green spots reduced, while chartreuse and yellow spots emerged indicating the progressive aggregation of GNPs. The color of spots and their brightness were used to estimate the number of GNPs in a cluster. Small GNP clusters with few GNPs show green colors and clusters with more GNPs show yellow-orange color.

Group 1 has 1–3 GNPs in the cluster; the second group has 4–6 GNPs; the group 3 has 7–12 GNPs; and the group 4 with \(> 12\) GNPs. Statistics of cluster number were collected from 33 to 46 cells and an ANOVA analysis of variance was used to determine the p-value of less than 0.005. Group 1 clusters appeared at the cell membrane via endocytosis and many of them were recycled back to the extracellular media. In our analysis, group 1 plays the role of the source with constant influx described by Eq. (2). This approximation could lead to the discrepancy at small times and should be further tested in experiment. Integrating the exact solution shown in Eq. (11) over the respective range of x, we found the analytical prediction for the number of GNP clusters in the corresponding group 2, 3 and 4 (see red bars in the insets of Figs. 2 and 3). These predictions were compared with the values found in experiments (Wang et al. 2016) (see blue bars in insets of Figs. 2 and 3). This comparison allowed us to choose parameters of the model (such as J, K and \(\gamma\)) such that the analytical predictions of the number of GNP clusters matched with the experiments. Most importantly, we show that our exact analytical solution is more accurate than the asymptotic steady-state structural density Eq. (13) in predicting the number of GNP clusters (see yellow bars in the insets of Figs. 2 and 3).

Power-law \(x^{-3/2}\) asymptotic of steady-state structural density of GNP-carrying endosomes

The approximate steady-state solution of Eq. (11), \(n_{\text{st}}(x)\), was obtained by Foret and co-workers for large x [see Eq. (1) in Foret et al. (2012)]. This solution behaves as a power-law with an exponential truncation.

Let us show that the distribution given by Eq. (11) decays as a power-law for increasing cluster size x, \(n_{\text{st}}(x) \sim x^{-3/2}\). This is a well-known result for the stationary solution of the both discrete and continuous Smoluchowski’s equations with injection (Hayakawa 1987; Takayasu 1989; Cueille and Sire 1998). Using symmetry properties of the modified Bessel functions \(I_0(-z) = I_0(z)\), \(I_1(-z) = - I_1(z)\) and leading terms of their asymptotic expansions for large z

we obtain the well-known power-law \(x^{-3/2}\) asymptotic behavior of the steady-state structural density of GNPs

where \(m=\kappa ^2 x_0^{-1}/\left( 2Q x_0 + \kappa ^2 \right)\). In Eq. (13), the power-law has an exponential cut-off \(\exp ( -m x)\). In Figs. 2 and 3, the asymptotic steady-state structural density Eq. (13) is compared with function Eq. (11). It should be emphasized that the natural appearance of the power-law \(x^{-3/2}\) with the exponential truncation \(\exp ( -m x)\) in cluster size distribution is a critical part of the exact analytical solution found in this paper. This natural truncation makes the presented model much more realistic and attractive to biology and experimentalists.

Unsteady-state density

The Laplace transform of the unsteady-state density as the solution of Eq. (6) can be obtained analytically (see “Appendix”). However, it is challenging to find its inverse transformation. Therefore, to study the time evolution of the structural density, \(n(x,\tau )\), we will use another analytical approach, the essence of which is as follows. Since the density function at any time is bounded between the initial distribution \(n_0(x)\) (which is known) and the stationary solution (11) (to which it approaches asymptotically with increasing time), we will use the method of stitching the analytical solution (Nayfeh 2000; Alexandrov and Galenko 2020).

Let us approximate the time-dependent distribution function \(n(x,\tau )\) as

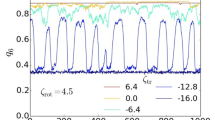

where \(b_0(\tau )\) and \(b_{st}(\tau )\) are the stitching functions satisfying the following conditions: \(b_0(\tau )\rightarrow 0\) at large times and \(b_{st}(\tau )\rightarrow 0\) at small times. The stitching functions must be chosen by comparing theory and experimental data. A similar approach has been used in Wang et al. (2016) where the integrated rate equations were introduced to describe the time evolution of the GNP clusters in 4 groups. To compare with the experiment in Wang et al. (2016), we integrate Eq. (14) to get the number of endosomes with clusters containing 4–6, 7–12 and more than 12 GNPs. Since the initial number of endosomes in each group was difficult to determine due to different conditions, we treated it as a fitting parameter. We have used \(b_0(\tau )=1/\tau\), \(b_{st}(\tau )=\tau\) as the stitching functions and the stationary number of endosomes given in the insets of Figs. 2 and 3. The results shown in Figs. 4 and 5 for two cells are in good agreement with experimental data of Wang et al. (2016).

Time-dependent clustering of GNPs in endosomes for CL1-0 cells. Comparison of the number of endosomes \(\Sigma\) with clusters containing 4–6, 7–12 and more than 12 GNPs obtained by integration of time-dependent density \(n(x,\tau )\) Eq. (14) (the dashed, the dashed-dotted and the dotted curves) with the experimental data of Wang et al. (2016) (the lines with symbols and error bars) for CL1-0 cells. Here \(\tau =K t\) is the dimensionless time. The initial number of endosomes in each group was 100 (endosomes with clusters containing 4–6), 100 (containing 7–12 clusters) and 15 (containing \(>12\) clusters). Experimental data points were acquired starting from \(t=1\) h (Wang et al. 2016)

Time-dependent clustering of GNPs in endosomes for Beas-2B cells. Comparison of the number of endosomes \(\Sigma\) with clusters containing 4–6, 7–12 and more than 12 GNPs obtained by integration of time-dependent density \(n(x,\tau )\) Eq. (14) (the dashed, the dashed-dotted and the dotted curves) with the experimental data of Wang et al. (2016) (the lines with symbols and error bars) for Beas-2B cells. Here \(\tau =K t\) is the dimensionless time. The initial number of endosomes in each group was 73 (endosomes with clusters containing 4–6), 23 (containing 7–12 clusters) and 2 (containing \(>12\) clusters). Experimental data points were acquired starting from \(t=1\) h (Wang et al. 2016)

Conclusion

In this paper, we studied clustering of NPs inside cells using the Smoluchowski’s coagulation equation with injection. We found the exact analytical solution of Eq. (4) giving the steady-state NP cluster size density for all cluster sizes. This cluster density is in good agreement with experimental data on GNP distribution inside endosomes. We show that for clusters containing between 1 and 20 NPs, the exact density provides a more accurate description of the existing experimental data than the well-known approximate asymptotic power-law distribution. We also obtained the unsteady cluster distribution and compare it with the experimental data for time evolution of gold nanoparticle clusters in living cells. As an extension of our results it would be interesting to consider multiple stochastic mechanisms for cell-to-cell variability in nanoparticle uptake (Rees et al. 2019; Åberg et al. 2021).

Understanding the steady-state behavior of how nanoparticles cluster within intracellular endosomes is important as many nanoparticle-enhanced treatments for cancer are dependent on when nanoparticles have saturated the cancerous cells (Lin et al. 2015; Sung et al. 2017). Our model presents a theoretical framework to calculate such saturation times. Since the mechanisms of cytotoxicity of NPs depend on their transport, clustering and accumulation inside cells, our results will be useful for insuring safety of NPs applications (Elsaesser and Howard 2012; Yang et al. 2021). Finally, we should mention that our results are also applicable to clustering of lipid NPs which are nowadays the major delivery vehicles in gene therapies and RNA vaccines revolution (Editorial 2021; Hou et al. 2021).

Availability of data and materials

All data related to this study are present in the paper.

References

Åberg C, Piattelli V, Montizaan D, Salvati A (2021) Sources of variability in nanoparticle uptake by cells. Nanoscale 13(41):17530–17546

Alexandrov DV, Galenko PK (2020) The shape of dendritic tips. Philos Trans R Soc A 378:20190243

Braga CB, Kido LA, Lima EN, Lamas CA, Cagnon VH, Ornelas C, Pilli RA (2020) Enhancing the anticancer activity and selectivity of goniothalamin using pH-sensitive acetalated dextran (Ac-Dex) nanoparticles: a promising platform for delivery of natural compounds. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 6(5):2929–2942

Castro M, Lythe G, Smit J, Molina-París C (2021) Fusion and fission events regulate endosome maturation and viral escape. Sci Rep 11(1):1–13

Cohen AM (2007) Numerical methods for Laplace transform inversion. Springer, New York

Cueille S, Sire C (1998) Droplet nucleation and Smoluchowski’s equation with growth and injection of particles. Phys Rev E 57:881–900

Ditkin VA, Prudnikov AP (1965) Integral transforms and operational calculus. Pergamon Press, Oxford

Editorial (2021) Let’s talk about lipid nanoparticles. Nat Rev Mater. 6:99

Elsaesser A, Howard CV (2012) Toxicology of nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64(2):129–137

Fedotov S, Alexandrov D, Starodumov I, Korabel N (2022) Stochastic model of virus-endosome fusion and endosomal escape of pH-responsive nanoparticles. Mathematics 10(3):375

Figueroa SM, Fleischmann D, Goepferich A (2021) Biomedical nanoparticle design: what we can learn from viruses. J Control Release 329:552–569

Foret L, Dawson JE, Villaseñor R, Collinet C, Deutsch A, Brusch L, Zerial M, Kalaidzidis Y, Jülicher F (2012) A general theoretical framework to infer endosomal network dynamics from quantitative image analysis. Curr Biol 22:1381

Ghosh P, Han G, De M, Kim CK, Rotello VM (2008) Gold nanoparticles in delivery applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60:1307

Hainfeld JF, Slatkin DN, Smilowitz HM (2004) The use of gold nanoparticles to enhance radiotherapy in mice. Phys Med Biol 49:309

Haume K, Rosa S, Grellet S, Smiałek MA, Butterworth KT, Solov’yov AV, Prise KM, Golding J, Mason NJ (2016) Gold nanoparticles for cancer radiotherapy: a review. Cancer Nanotechnol 7:8

Hayakawa H (1987) Irreversible kinetic coagulations in the presence of a source. J Phys A Math Gen 20:801–805

Her S, Jaffray DA, Allen C (2017) Gold nanoparticles for applications in cancer radiotherapy: mechanisms and recent advancements. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 109:84

Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R, Dong Y (2021) Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater 6(12):1078–1094

Klapproth AP, Schuemann J, Stangl S, Xie T, Li WB, Multhoff G (2021) Multi-scale Monte Carlo simulations of gold nanoparticle-induced DNA damages for kilovoltage X-ray irradiation in a xenograft mouse model using TOPAS-nBio. Cancer Nanotechnol 12(1):1–18

Kong F-Y, Zhang J-W, Li R-F, Wang Z-X, Wang W-J, Wang W (2017) Unique roles of gold nanoparticles in drug delivery, targeting and imaging applications. Molecules 22(9):1445

Korabel N, Han D, Taloni A, Pagnini G, Fedotov S, Allan V, Waigh TA (2021) Local analysis of heterogeneous intracellular transport: slow and fast moving endosomes. Entropy 23(8):958

Lin Y, McMahon SJ, Paganetti H, Schuemann J, Yuting L, Stephen JM, Harald P, Jan S (2015) Biological modeling of gold nanoparticle enhanced radiotherapy for proton therapy. Phys Med Biol 60:4149

Liu M, Li Q, Liang L, Li J, Wang K, Li J, Lv M, Chen N, Song H, Lee J, Shi J, Wang L, Lal R, Fan C (2017) Real-time visualization of clustering and intracellular transport of gold nanoparticles by correlative imaging. Nat Commun 8:15646

Lodhi MS, Khan MT, Aftab S, Samra ZQ, Wang H, Wei DQ (2021) A novel formulation of theranostic nanomedicine for targeting drug delivery to gastrointestinal tract cancer. Cancer Nanotechnol 12(1):1–27

Ma XY, Hill BD, Hoang T, Wen F (2021) Virus-inspired strategies for cancer therapy. Seminars in cancer biology. Elsevier, London

McCullogh A, Bennie L, Coulter JA, McCarthy HO, Dromey BRD, Quinn P, Villagomez-Bernabe B, Currell F (2019) Nuclear uptake of gold nanoparticles deduced using dual-angle X-ray fluorescence mapping. Particle Particle Syst Charact 36:1900140

Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R (2021) Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20(2):101–124

Nayfeh AH (2000) Perturbation methods. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim

Panov V, Minigalieva I, Bushueva T, Fröhlich E, Meindl C, Absenger-Novak M, Shur V, Shishkina E, Gurvich V, Privalova L (2020) Some peculiarities in the dose dependence of separate and combined in vitro cardiotoxicity effects induced by CdS and PbS nanoparticles with special attention to hormesis manifestations. Dose-Response 18(1):1559325820914180

Park S-M, Aalipour A, Vermesh O, Yu JH, Gambhir SS (2017) Towards clinically translatable in vivo nanodiagnostics. Nat Rev Mater 2(5):1–20

Peckys DB, de Jonge N (2011) Visualizing gold nanoparticle uptake in live cells with liquid scanning transmission electron microscopy. Nano Lett 11:1733

Peckys DB, de Jonge N (2014) Gold nanoparticle uptake in whole cells in liquid examined by environmental scanning electron microscopy. Microsc Microanal 20:189

Peukert D, Kempson I, Douglass M, Bezak E (2018) Metallic nanoparticle radiosensitisation of ion radiotherapy: a review. Phys Med 47:121

Rees P, Wills JW, Brown MR, Barnes CM, Summers HD (2019) The origin of heterogeneous nanoparticle uptake by cells. Nat Commun 10(1):1–8

Sadauskas E, Jacobsen NR, Danscher G, Stoltenberg M, Vogel U, Larsen A, Kreyling W, Wallin H (2009) Biodistribution of gold nanoparticles in mouse lung following intratracheal instillation. Chem Cent J 3:16

Smith AJ, Wells CG, Kraft M (2018) A new iterative scheme for solving the discrete Smoluchowski equation. J Comput Phys 352:373–387

Stefančíková L, Porcel E, Eustache P, Li S, Salado D, Marco S, Guerquin-Kern J-L, Réfrégiers M, Tillement O, Lux F, Lacombe S (2014) Cell localisation of gadolinium-based nanoparticles and related radiosensitising efficacy in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Nanotechnol 5:6

Sukhanova A, Bozrova S, Sokolov P, Berestovoy M, Karaulov A, Nabiev I (2018) Dependence of nanoparticle toxicity on their physical and chemical properties. Nanoscale Res Lett 13(1):1–21

Sung W, Ye S-J, McNamara AL, McMahon SJ, Hainfeld J, Shin J, Smilowitz HM, Paganetti H, Schuemann J (2017) Dependence of gold nanoparticle radiosensitization on cell geometry. Nanoscale 9:5843

Takayasu H (1989) Steady-state distribution of generalized aggregation system with injection. Phys Rev Lett 63:2563–2565

Villagomez-Bernabe B, Currell FJ (2019) Physical radiation enhancement effects around clinically relevant clusters of nanoagents in biological systems. Sci Rep 9:1–10

Villagomez-Bernabe B, Ramos-Méndez J, Currell FJ (2021) On the equivalence of the biological effect induced by irradiation of clusters of heavy atom nanoparticles and homogeneous heavy atom-water mixtures. Cancers 13:2034

Wang SH, Lee CW, Tseng FG, Liang KK, Wei PK (2016) Evolution of gold nanoparticle clusters in living cells studied by sectional dark-field optical microscopy and chromatic analysis. J Biophotonics 9:738–749

Wannasarit S, Wang S, Figueiredo P, Trujillo C, Eburnea F, Simón-Gracia L, Correia A, Ding Y, Teesalu T, Liu D (2019) A virus-mimicking pH-responsive acetalated dextran-based membrane-active polymeric nanoparticle for intracellular delivery of antitumor therapeutics. Adv Funct Mater 29(51):1905352

Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG (2009) Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:129

Yang W, Wang L, Mettenbrink EM, DeAngelis PL, Wilhelm S (2021) Nanoparticle toxicology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 61:269–289

Zhou K, Wang Y, Huang X, Luby-Phelps K, Sumer BD, Gao J (2011) Tunable, ultrasensitive pH-responsive nanoparticles targeting specific endocytic organelles in living cells. Angew Chem Int Ed 50:6109–6114

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

NK, FC and SF acknowledge financial support from EPSRC Grant No. EP/V008641/1. DVA and SF are grateful to the Russian Science Foundation for the financial support (Project No. 20-61-46013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DA and SF provide mathematical analysis of Smoluchowski’s equation. NK performed computer simulations. All authors wrote the paper, interpreted the data, edited the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

A transient behavior of endosomes can be studied using Eq. (6) supplemented with the initial distribution \({\tilde{n}}(0)={\tilde{n}}_0\). Introducing the new function \({\tilde{y}}(p,\tau )={\tilde{n}}(p,\tau )-\lambda (\tau ) -\kappa\), we arrive at the following Riccati equation supplemented with the initial condition

Substituting \(\lambda (\tau ) = {\tilde{n}}\) at \(p=0\) into Eq. (6), we obtain the differential equation for \(\lambda\) in the unsteady-state case:

Its solution determines a transient behavior of the total number of the GNPs carrying endosomes per cell:

where

In particular, for \(\kappa =0\) and \(\lambda (0)=0\), we obtain (Foret et al. 2012)

where \(\sqrt{2Qx_0}\) is the steady value of \(\lambda (\tau )\) as \(\tau \rightarrow \infty .\) Combining equations (15) and (17), we get the following equation for the shifted density of the GNPs carrying endosomes \({\tilde{y}}\) in the Laplace space

Its solution is given by

where

In particular, for \(\kappa =0\) and \({\tilde{y}}(0) =0\), we obtain

where

An important point is that the inverse Laplace transform of the analytical solution (20) is unknown. This means that the inverse Laplace transform must be found numerically. Such a problem in itself is non-trivial and is a topic for a separate scientific study (Cohen 2007).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alexandrov, D.V., Korabel, N., Currell, F. et al. Dynamics of intracellular clusters of nanoparticles. Cancer Nano 13, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12645-022-00118-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12645-022-00118-x