Abstract

Background

Though subjective, poor self-rated health (SRH) has consistently been shown to predict cardiovascular disease (CVD). The underlying mechanism is unclear. This study evaluates the associations of SRH with biomarkers for CVD, aiming to explore potential pathways between poor SRH and CVD.

Methods

Based on the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cardiovascular Cohort study, a targeted proteomics approach was used to assess the associations of SRH with 88 cardiovascular risk proteins, measured in plasma from 4521 participants without CVD. The false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. Covariates taken into consideration were age, sex, traditional CVD risk factors (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication, diabetes, body mass index, smoking), comorbidity, life-style and psycho-social factors (education level, living alone, alcohol consumption, low physical activity, psychiatric medication, sleep duration, and unemployment).

Results

Age and sex-adjusted associations with SRH was found for 34 plasma proteins. Nine of them remained significant after adjustments for traditional CVD risk factors. After further adjustment for comorbidity, life-style and psycho-social factors, only leptin (β = − 0.035, corrected p = 0.016) and C–C motif chemokine 20 (CCL20; β = − 0.054, corrected p = 0.016) were significantly associated with SRH.

Conclusions

Poor SRH was associated with raised concentrations of many plasma proteins. However, the relationships were largely attenuated by adjustments for CVD risk factors, comorbidity and psycho-social factors. Leptin and CCL20 were associated with poor SRH in the present study and could potentially be involved in the SRH–CVD link.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

How people rate their own health is a subjective but surprisingly sensitive and reliable assay for evaluation of general well-being. A meta-analysis of 22 prospective, community-based cohort studies has reported that compared to participants with “excellent” self-rated health (SRH), mortality risk among those who rated their health as “poor” has almost doubled even after adjustment for co-morbidity, depression, and cognitive and functional status [1]. The association of poor SRH with mortality is at least partly driven by its association with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). This hypothesis is supported by a meta-analysis demonstrating a strong association between poor SRH and incidence of cardiovascular mortality in populations with or without previous CVD [2]. For people without prior CVD, a significant predictive value of poor SRH for onset of CVD events has also been observed by several cohort studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

The mechanisms underlying the association between poor SRH and CVD remain unclear. SRH is a comprehensive indicator of health status that closely associates with material, behavioral, personality and psycho-social factors [10, 11]. These socioeconomic inequalities affect individual’s healthcare resource use and predisposition to better or worse health, including CVD risk and mortality [12,13,14,15], which could be one important reason behind the association between poor SRH and CVD. SRH may also influence immune responses or autonomic nervous system [16,17,18,19], or reflect to some extent the functional impairment, the physical morbidity [3, 20, 21], and the objective measures of cardiovascular risk [2, 3, 7, 9]. For people with poor SRH, certain circulating inflammatory markers have been observed to be elevated, including the more commonly studied interleukin (IL)-6 and C-reactive protein [17, 22,23,24,25] and others (IL-1β, IL-1rα, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, tumor necrosis factor-α, etc.) [16, 19, 26].

In this study, we aimed to use a recently-developed targeted proteomics approach to explore the change in cardiovascular proteomics associated with SRH. Being highly sensitive and specific, the implement of this proteomics methodology may provide a novel insight into biologically plausible mechanistic pathways between poor SRH and CVD.

Materials and methods

Participants

The Malmö Diet and Cancer (MDC) study is a large prospective cohort study among residents living in the Swedish town of Malmö [27]. Between 1991 to 1994, 6103 randomly selected participants from the MDC study were invited to participate in the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cardiovascular Cohort (MDC-CV) study aiming at investigating the epidemiology of carotid artery atherosclerosis [28]. Among them, 5540 participants undertook a second visit for collecting fasting plasma samples, of which 5002 had complete data on covariates. Out of these, 307 subjects with insufficient plasma stored for assessing proteins and 167 subjects who did not pass the internal quality control for the protein analyses were excluded. Of the remaining 4528 participants, we further excluded those with prevalent CVDs (n = 7), leading a final sample size of 4521 for cohort analysis (1763 men and 2758 women. mean age, 57.5 ± 5.97 years) (Fig. 1).

Written informed consent have been obtained from all participants. The study has been approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden (LU 51/90) and was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Self-rated health

Self-rated health was assessed on an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 7, based on subjects’ answers to a questionnaire item: “How do you feel right now, physically and mentally, with respect to your health and well-being?”. While “1” indicates “feel very bad, could not feel worse”, “7” indicates “feel very well, could not feel better”.

Proteomic analysis

Fasting EDTA-plasma samples were stored at − 80 °C immediately after collection until protein analysis. Ninety-two CVD-related proteins were simultaneously measured by the SciLifeLab analysis service (Uppsala, Sweden) using Proseek® Multiplex CVD I96×96 reagent kit [29]. The reagents are based on proximity extension assay (PEA) technology, where 92 pairs of oligonucleotide-labeled antibody probes were used to detect the corresponding target proteins in a homogeneous assay [30, 31]. Only correctly matched probe pairs will generate detectable and quantifiable signals for a Fluidigm® Biomark™ HD real-time PCR platform, making the technology of significantly higher specificity and sensitivity than traditional multiplex immunoassays [29,30,31]. Quantitative PCR quantification cycles (Cq) corrected for technical variation by the Inter-plate Control (IPC) generate “Normalized Protein Expression (NPX)” values, which are arbitrary units on log2 scale. A higher NPX value corresponds to a higher protein level. Samples deviate less than ± 0.3 from the median value for the incubation and detection controls will pass quality control [32]. The mean intra-assay (within-run) and inter-assay (between-run) coefficient of variations were 8% (range 4–13%) and 15% (range 11–39%), respectively. Detailed introduction of cardiovascular proteomic panel, PEA technology, assay performance, quality control and validation is available on the Olink webpage (http://www.olink.com). Four proteins had a call rate < 75%: extracellular newly identified RAGE-binding (EN-RAGE, n = 101), beta-nerve growth factor (Beta-NGF, n = 451), IL-4 (n = 12), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP, n = 636) were removed from main analyses (none of them were significantly associated with SRH, data not shown). This resulted in 88 proteins for final analyses. Proteins with levels below the lower limit of detection (LOD) were considered to have a value of LOD/2.

Other measurements and definitions

Information on alcohol consumption and smoking, medication (anti-hypertensive and psychiatric medication), comorbidity (i.e. ventricular ulcer, cancer, asthma/chronic bronchitis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and kidney stone), physical activity, education level, living alone, average sleep duration, and unemployment were obtained from a health questionnaire completed by the participants and their 7-day personal diary. Smoking was treated as a two-category variable: smokers or non-smokers. Men with alcohol intake > 40 g/day or women with alcohol intake > 30 g/day were considered to have high alcohol consumption. Use of anti-hypertensive and psychiatric drug was identified based on the drugs listed by participants. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification codes N05 and N06 were used for psychiatric drugs and C02, C03, C07 and C08 were used for anti-hypertensive drugs. Subjects with self-reported diabetes or diabetes treatment or with a fasting venous whole blood glucose higher than 6.1 mmol/L (corresponding to 7.0 mmol/L when using fasting plasma glucose to diagnose diabetes [33]) were considered to have diabetes. An overall leisure-time physical activity score was calculated by multiplying an activity-specific intensity coefficient and the corresponding duration [34]. People in the lowest quartile of physical activity score were considered to have low physical activity. People with a minimum of a university degree were considered to have a high educational level. They also reported whether they were living alone and whether they were unemployed. A weighted average sleep duration was calculated for individuals based on average sleep duration (hours) on weekdays and weekends [(weekday × 5) + (weekend × 2)/7], and then categorized as (≤ 6, 6–8, ≥ 8 h). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Blood pressure (mmHg) was measured after the participants had rested for 10 min in a supine position. Blood samples were drawn after an overnight fast. LDL concentration (mmol/L) was estimated using Friedewald’s formula [35].

Incidence of CVD and mortality up to December 31st, 2016, was monitored by data linkage with the Swedish in-patient register and the cause of death register. Incident CVD included new cases of coronary event (fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction or death due to ischemic heart disease) or stroke diagnosed according to the International Classification of Diseases 9th or 10th revision [36].

Statistical analysis

Protein values were Z-score standardized in all analyses. Pearson’s partial correlation tests were conducted between each pair of proteins after adjusting for age and sex. Baseline characteristics for subjects included in this study (n = 4521) are demonstrated for those with SRH higher or lower than the median level (SRH = 5). Continuous variables are all normally distributed and thus presented as mean ± SD, while categorical variables are presented as percentages. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using univariate Chi-square or student t-tests. The hazard ratio of SRH for incident CVD (or mortality) was calculated using Cox proportional hazard regression models, with time-scale defined as time to follow-up until incident CVD (or mortality), emigration, death or end of follow-up (2016-12-31). Since only few participants scored their health as 1 or 2 (n = 46 and 71, respectively), participants with an SRH value of 1–3 were combined into one group.

Linear regression models were separately conducted for every single protein to investigate its association with SRH (as the independent variable). In primary analyses, only age and sex were adjusted for and forest plot was used to visualize the associations. In a second model, traditional cardiovascular risk factors were included (age, sex, smoking, LDL-cholesterol, diabetes, BMI, systolic blood pressure and anti-hypertensive treatment). Finally, comorbidity, life-style and psycho-social risk factors were added to the model (comorbidity, alcohol consumption, education level, living alone, low physical activity, psychiatric medication, average sleep duration, and unemployment). The covariates were examined for multi-collinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and it was found that VIF was < 2 for all independent variables. Since multiple testing was involved in both analyses, p values were corrected for false discovery rate using the Benjamini and Hochberg method [37]. For proteins of significant associations with SRH after correction, possible effect modifications by covariates were explored by introducing an interaction term in the multivariate model (one term per covariate at a time). A two-tailed p value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the study population according to their SRH values are shown in Table 1. As compared to participants with lower SRH (median: 5), those with higher SRH were more likely to be older, or have lower BMI or systolic blood pressure. A greater proportion of them were males and non-smokers. They also tended to be more physically active and less likely to live alone, take anti-hypertensive or psychiatric medication, or have diabetes or other comorbidities. A greater proportion of them slept 6–8 h per day, and a smaller proportion of them slept less than 6 h per day.

The predictive value of poor SRH for adverse outcomes

During the follow-up, 1445 deaths and 830 CVD events were recorded. Worse SRH was associated with a graded increase in risk across all outcomes, which persisted after sequential adjustment. In models adjusted for age, sex, traditional CVD risk factors, comorbidity, life-style and psycho-social factors, participants in the poor SRH scores had a markedly elevated risk of CVD (HR, 1.64; 95% CI 1.25–2.15; p for trend < 0.0001) and a slightly elevated risk of mortality (HR, 1.20; 95% CI 0.97–1.47; p for trend = 0.02) compared with those with a SRH score of 7. In total, results from the Cox regression analyses (Table 2) supported a predictive value of poor SRH for adverse outcomes (i.e. CVD and mortality).

Plasma proteins in relation to SRH

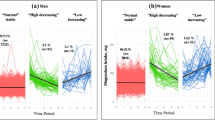

As depicted in Fig. 2, high correlations can be observed across pairs of proteins. After adjusting for age and sex, nominal significant associations (p < 0.05) were found of SRH with 42 of the 88 proteins examined (Fig. 3). Thirty-four of them remained significant after correcting for multiple testing (FDR < 5%).

After further adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, BMI, LDL, diabetes, systolic blood pressure and antihypertensive treatment) nine proteins remained significant after correcting for multiple testing (leptin, CCL20, IL-1 receptor antagonist protein, IL-6, matrix metalloproteinase-7, lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1, urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor, matrix metalloproteinase-12, follistatin; corrected p < 0.001, < 0.001, = 0.011, = 0.015, = 0.021, = 0.034, = 0.034, = 0.034, = 0.034, respectively). When comorbidity and psycho-social factors were added to the model, eight plasma proteins were related to SRH with nominal significance; two of them (leptin, β = − 0.035, corrected p = 0.016 and CCL20, β = − 0.054, corrected p = 0.016) were significant after correction for multiple testing; Table 3).

Interaction tests showed that the adjusted association between leptin and SRH was modified by sex, BMI, alcohol consumption, and systolic blood pressure (interaction p = 0.019, < 0.001, = 0.033, = 0.035, respectively), while the association between CCL20 and SRH was modified by smoking (interaction p = 0.006). Results of the corresponding subgroup analyses are presented in Table 3. The association of SRH with leptin was relatively strong among males (n = 1763), or people with obesity (n = 2298) or high alcohol consumption (n = 158) or elevated systolic blood pressure (n = 2441). The association between SRH and CCL20 was significant among non-smokers (n = 3353) but not smokers. The association between SRH and mortality and CVD, respectively, was only marginally changed after additional adjustment for leptin and CCL20 in multivariate Cox regression models. The hazard ratios of SRH 1–3 versus 7 for CVD and mortality decreased from 1.64 (1.25, 2.15) to 1.62 (1.23, 2.13), and from 1.20 (0.97, 1.47) to 1.18 (0.96, 1.46), respectively (data not shown).

Discussion

Many epidemiological studies reported that poor SRH is a strong predictor for subsequent mortality, even after extensive adjustments for other potential risk factors [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Consistent with these previous observations, our results showed that the participants in the poor SRH scores had a markedly elevated risk of CVD and mortality events. The underlying biological cause for this relationship is unclear. In this study, we extend existing literature on the SRH–CVD link by applying a proteomic analysis. Poor SRH was associated with raised concentrations of many plasma proteins after adjustments for age and sex. After adjustments for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, nine proteins were still significantly associated with SRH. The relationships were largely attenuated by further adjustments for comorbidity and psycho-social factors. For two proteins, leptin and CCL20, we found significant relationships even after adjustments for multiple risk factors, and these proteins could potentially have a role in the SRH–CVD link beyond traditional risk factors.

Self-rated health is a summative measure of a person’s overall assessment of health status. As such, many psychological as well as medical factors could affect SRH. It is noteworthy that some variables, which usually are related to poor health, were unrelated to SRH in this study (e.g. LDL-cholesterol, education, and unemployment), while the relationships with poor SRH were strong for e.g. smoking, diabetes and anti-hypertensive medication (Table 1). It is not possible to make any conclusions of the causal relationships between SRH and the various plasma proteins. However, we conclude that poor SRH was significantly associated with many of the plasma proteins in this targeted CVD panel. We also conclude that traditional CVD risk factors, as well as factors related to comorbidity, life-style or psycho-social factors largely account for the relationships between SRH and plasma proteins.

Inflammation has been firmly established as crucial to the development of CVD [38]. The activation of local arterial inflammation or system immune responses could together lead to initiation or progression of atherosclerotic plaques, and even complicated atherosclerotic lesions. Meanwhile, poor SRH could be linked to immune responses through the elevation of circulating inflammatory and immune cytokines [16, 17, 19, 22,23,24,25,26]. These facts raised a possibility that immune responses may be the underlying mechanism to explain the relationship between poor SRH and CVD. In the current study, using a targeted proteomics approach, 34 proteins were found to be significantly associated with SRH after adjusting by age and sex. Noteworthily, many of these proteins were related to immune or inflammatory responses.

After multivariate adjustment, an association between poor SRH and CCL20 was still observed in our study. CCL20 is a recently discovered CC chemokine which functions together with its selective receptor CCR6 to mediate the chemoattraction of immature dendritic cells and effector and memory T- and B-cells [39]. Whereas this association has not yet been reported before, a pivotal role of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in the pathophysiology of depression have already been demonstrated in recent studies [40, 41]. CCL20 can be produced by Th17 [42] and is important for Th17 cell migration and tissue inflammation [43]. The CCL20–CCR6 axis in epithelial cells of choroid plexus has been proposed as a key point for Th17 cells to enter the central nervous system, which may further trigger local inflammation [44, 45] and therefore might potentially contribute to poor SRH.

The coexistence of increased circulating leptin and depression has been previously demonstrated, though in studies with small sample sizes and clinical heterogeneity [46, 47]. In addition, only two studies [48, 49] have investigated the association between SRH and leptin. In this prospective study, after multivariate adjustments, the association of poor SRH with higher leptin was significant in both sexes and was relatively stronger in men (interaction p = 0.019). Leptin is an adipose-derived hormone that can control body weight by inhibiting appetite and increasing energy expenditure [50]. However, the anti-obesity role of leptin is usually thwarted by leptin resistance, which leads to elevated leptin levels in obesity [51]. Leptin resistance has also been proposed as a potential interface of inflammation and metabolic disturbance linking obesity and CVD [52]. In the present study, a much stronger association between poor SRH and high leptin was observed in participants with BMI higher vs. lower than 25 kg/m2 (interaction p < 0.001). It is therefore speculated that for people with poor SRH, obesity accompanied by elevated leptin concentration and leptin resistance may contribute to some extent the subsequent cardiovascular risk [53]. As an obesity-related disorder, leptin resistance may be linked with mood status via several biological pathways [54,55,56]. In adult mice, targeted deletion of leptin receptors in the hippocampus and cortex leads to hyperleptinemia [55] and depression-related behaviors [54]. Leptin receptor deficiency is also associated with resistance to anti-depressive medications [55]. Thus, a link among elevated leptin, poor SRH, and subsequent risk for CVD could be explained.

Strengths of this study included a large sample size and the application of a highly sensitive and specific proteomics approach. However, the reliability of our results is limited by lack of replication samples. The 88 proteins measured in this study only constitute a minor subpopulation of the CVD-related proteins, and their associations with SRH were only cross-sectionally investigated. Since SRH appears to be a summative assessment of various aspects of health, we cannot rule out residual confounding from some aspects that can hardly be measured, or reverse causality. Therefore, the exact biological mechanisms underlying the association between SRH and cardiovascular outcomes cannot be illustrated in the present study. Nevertheless, we supported a biological change associated with subjective measurement, which helps to explain the predictive value of SRH for future outcomes.

Conclusions

Poor SRH was associated with raised concentrations of many plasma proteins. However, the relationships were largely attenuated by adjustments for traditional CVD risk factors and factors related to comorbidity, life-style and psycho-social factors. Leptin and CCL20 were associated with poor SRH after multiple adjustments and could potentially be involved in the SRH–CVD link.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study belongs to Lund University and applications for studies using the MDC cohort can be addressed to the MKC steering committee. Email: Anders.Dahlin@med.lu.se.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- Cq:

-

quantification cycle

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- FDR:

-

false discovery rate

- LOD:

-

lower limit of detection

- MDC:

-

Malmö Diet and Cancer

- MDC-CV:

-

Malmö Diet and Cancer Cardiovascular Cohort

- NPX:

-

Normalized Protein Expression

- PEA:

-

proximity extension assay

- SRH:

-

self-rated health

- Th17:

-

T helper 17

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- AGRP:

-

agouti-related protein

- AM:

-

adrenomedullin

- Beta-NGF:

-

beta-nerve growth factor

- BNP:

-

natriuretic peptides B

- CA-125:

-

ovarian cancer-related tumor marker CA 125

- CASP-8:

-

caspase-8

- CCL20:

-

C–C motif chemokine 20

- CCL3:

-

C–C motif chemokine 3

- CCL4:

-

C–C motif chemokine 4

- CD40:

-

CD40L receptor

- CD40L:

-

CD40 ligand

- CHI3L1:

-

chitinase-3-like protein 1

- CSF1:

-

macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1

- CSTB:

-

cystatin-B

- CTSD:

-

cathepsin D

- CTSL1:

-

cathepsin L1

- CX3CL1:

-

fractalkine

- CXCL1:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine 1

- CXCL16:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine 16

- CXCL6:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine 6

- DKK-1:

-

dickkopf-related protein 1

- ECP:

-

eosinophil cationic protein

- EGF:

-

epidermal growth factor

- EN-RAGE:

-

protein S100-A12

- ESM-1:

-

endothelial cell-specific molecule 1

- FABP4:

-

fatty acid-binding protein, adipocyte

- FAS:

-

tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6

- FGF-23:

-

fibroblast growth factor 23

- FS:

-

follistatin

- GAL:

-

galanin peptides

- Gal-3:

-

galectin-3

- GDF-15:

-

growth/differentiation factor 15

- GH:

-

growth hormone

- HB-EGF:

-

heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor

- HGF:

-

hepatocyte growth factor

- hK11:

-

kallikrein-11

- HSP27:

-

heat shock 27 kDa protein

- IL-16:

-

interleukin-16

- IL-18:

-

interleukin-18

- IL-1RA:

-

interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein

- IL-4:

-

interleukin-4

- IL-6:

-

interleukin-6

- IL-6RA:

-

interleukin-6 receptor subunit alpha

- IL-8:

-

interleukin-8

- IL27-A:

-

interleukin-27 subunit alpha

- ITGB1BP2:

-

melusin

- KIM-1:

-

kidney injury molecule-1

- KLK6:

-

kallikrein-6

- LEP:

-

leptin

- LOX-1:

-

lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1

- mAmp:

-

membranebound aminopeptidase P

- MB:

-

myoglobin

- MCP-1:

-

monocyte chemotactic protein 1

- MMP-1:

-

matrix metalloproteinase-1

- MMP-10:

-

matrix metalloproteinase-10

- MMP-12:

-

matrix metalloproteinase-12

- MMP-3:

-

matrix metalloproteinase-3

- MMP-7:

-

matrix metalloproteinase-7

- MPO:

-

myeloperoxidase

- NEMO:

-

NF-kappa-B essential modulator

- NTproBNP:

-

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- OPG:

-

osteoprotegerin

- PAPPA:

-

pappalysin-1

- PAR-1:

-

proteinase-activated receptor 1

- PDGF subunit B:

-

platelet-derived growth factor subunit B

- PECAM-1:

-

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule

- PlGF:

-

placenta growth factor

- PRL:

-

prolactin

- PSGL-1:

-

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1

- PTX3:

-

pentraxin-related protein PTX3

- RAGE:

-

receptor for advanced glycosylation end products

- REN:

-

renin

- RETN:

-

resistin

- SCF:

-

stem cell factor

- SELE:

-

E-selectin

- SIRT2:

-

SIR2-like protein 2

- SPON1:

-

spondin-1

- SRC:

-

proto-oncogene tyrosineprotein kinase Src

- ST2:

-

ST2 protein

- t-PA:

-

tissue-type plasminogen activator

- TF:

-

tissue factor

- TIE2:

-

angiopoietin-1 receptor

- TM:

-

thrombomodulin

- TNF-R1:

-

tumor necrosis factor receptor 1

- TNF-R2:

-

tumor necrosis factor receptor 2

- TNFSF14:

-

tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 14

- TRAIL:

-

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- TRAIL-R2:

-

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 2

- TRANCE:

-

TNF-related activation-induced cytokine

- U-PAR:

-

urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor

- VEGF-A:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor A

- VEGF-D:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor D

References

DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:267–75.

Mavaddat N, Parker RA, Sanderson S, Mant J, Kinmonth AL. Relationship of self-rated health with fatal and non-fatal outcomes in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e103509.

Rutledge T, Linke SE, Johnson BD, Bittner V, Krantz DS, Whittaker KS, Eastwood JA, Eteiba W, Cornell CE, Pepine CJ, Vido DA, Olson MB, Shaw LJ, Vaccarino V, Bairey Merz CN. Self-rated versus objective health indicators as predictors of major cardiovascular events: the NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:549–55.

van der Linde RM, Mavaddat N, Luben R, Brayne C, Simmons RK, Khaw KT, Kinmonth AL. Self-rated health and cardiovascular disease incidence: results from a longitudinal population-based cohort in Norfolk, UK. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65290.

Moller L, Kristensen TS, Hollnagel H. Self rated health as a predictor of coronary heart disease in Copenhagen, Denmark. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:423–8.

Ernstsen L, Nilsen SM, Espnes GA, Krokstad S. The predictive ability of self-rated health on ischaemic heart disease and all-cause mortality in elderly women and men: the Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT). Age Ageing. 2011;40:105–11.

Waller G, Janlert U, Norberg M, Lundqvist R, Forssen A. Self-rated health and standard risk factors for myocardial infarction: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006589.

Ul-Haq Z, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Association between self-reported general and mental health and adverse outcomes: a retrospective cohort study of 19,625 Scottish adults. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93857.

Grool AM, van der Graaf Y, Visseren FL, de Borst GJ, Algra A, Geerlings MI. Self-rated health status as a risk factor for future vascular events and mortality in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic atherosclerotic disease: the SMART study. J Intern Med. 2012;272:277–86.

Moor I, Spallek J, Richter M. Explaining socioeconomic inequalities in self-rated health: a systematic review of the relative contribution of material, psychosocial and behavioural factors. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71:565–75.

Goodwin R, Engstrom G. Personality and the perception of health in the general population. Psychol Med. 2002;32:325–32.

Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, Kunst AE, European Union Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in H. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2468–81.

Backholer K, Peters SAE, Bots SH, Peeters A, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Sex differences in the relationship between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71:550–7.

Hemmingsson T, Lundberg I. How far are socioeconomic differences in coronary heart disease hospitalization, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality among adult Swedish males attributable to negative childhood circumstances and behaviour in adolescence? Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:260–7.

Winkleby MA, Kraemer HC, Ahn DK, Varady AN. Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: findings for women from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. JAMA. 1998;280:356–62.

Lekander M, Elofsson S, Neve IM, Hansson LO, Unden AL. Self-rated health is related to levels of circulating cytokines. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:559–63.

Christian LM, Glaser R, Porter K, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf D, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Poorer self-rated health is associated with elevated inflammatory markers among older adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1495–504.

Jarczok MN, Kleber ME, Koenig J, Loerbroks A, Herr RM, Hoffmann K, Fischer JE, Benyamini Y, Thayer JF. Investigating the associations of self-rated health: heart rate variability is more strongly associated than inflammatory and other frequently used biomarkers in a cross sectional occupational sample. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0117196.

Unden AL, Andreasson A, Elofsson S, Brismar K, Mathsson L, Ronnelid J, Lekander M. Inflammatory cytokines, behaviour and age as determinants of self-rated health in women. Clin Sci. 2007;112:363–73.

Hirosaki M, Okumiya K, Wada T, Ishine M, Sakamoto R, Ishimoto Y, Kasahara Y, Kimura Y, Fukutomi E, Chen WL, Nakatsuka M, Fujisawa M, Otsuka K, Matsubayashi K. Self-rated health is associated with subsequent functional decline among older adults in Japan. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:1475–83.

Cabrero-Garcia J, Julia-Sanchis R. The Global Activity Limitation Index mainly measured functional disability, whereas self-rated health measured physical morbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:468–76.

Tanno K, Ohsawa M, Onoda T, Itai K, Sakata K, Tanaka F, Makita S, Nakamura M, Omama S, Ogasawara K, Ogawa A, Ishibashi Y, Kuribayashi T, Koyama T, Okayama A. Poor self-rated health is significantly associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in women, but not in men, in the Japanese general population. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73:225–31.

Shanahan L, Bauldry S, Freeman J, Bondy CL. Self-rated health and C-reactive protein in young adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;36:139–46.

Janszky I, Lekander M, Blom M, Georgiades A, Ahnve S. Self-rated health and vital exhaustion, but not depression, is related to inflammation in women with coronary heart disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:555–63.

Andreasson AN, Szulkin R, Unden AL, von Essen J, Nilsson LG, Lekander M. Inflammation and positive affect are associated with subjective health in women of the general population. J Health Psychol. 2013;18:311–20.

Warnoff C, Lekander M, Hemmingsson T, Sorjonen K, Melin B, Andreasson A. Is poor self-rated health associated with low-grade inflammation in 43,110 late adolescent men of the general population? A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009440.

Berglund G, Elmstahl S, Janzon L, Larsson SA. The Malmo Diet and cancer study. Design and feasibility. J Intern Med. 1993;233:45–51.

Hedblad B, Nilsson P, Janzon L, Berglund G. Relation between insulin resistance and carotid intima-media thickness and stenosis in non-diabetic subjects. Results from a cross-sectional study in Malmo, Sweden. Diabet Med. 2000;17:299–307.

Olink. CVD I 96 × 9. 2015. https://www.olink.com/content/uploads/2015/12/0696-v1.3-Proseek-Multiplex-CVD-I-Validation-Data_final.pdf. Accessed 22 Sept 2019.

Lundberg M, Eriksson A, Tran B, Assarsson E, Fredriksson S. Homogeneous antibody-based proximity extension assays provide sensitive and specific detection of low-abundant proteins in human blood. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e102.

Assarsson E, Lundberg M, Holmquist G, Bjorkesten J, Thorsen SB, Ekman D, Eriksson A, Rennel Dickens E, Ohlsson S, Edfeldt G, Andersson AC, Lindstedt P, Stenvang J, Gullberg M, Fredriksson S. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95192.

Cornelis MC, Gustafsson S, Arnlov J, Elmstahl S, Soderberg S, Sundstrom J, Michaelsson K, Lind L, Ingelsson E. Targeted proteomic analysis of habitual coffee consumption. J Intern Med. 2018;283:200–11.

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53.

Brunkwall L, Chen Y, Hindy G, Rukh G, Ericson U, Barroso I, Johansson I, Franks PW, Orho-Melander M, Renstrom F. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and genetic predisposition to obesity in 2 Swedish cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:809–15.

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502.

Bao X, Borne Y, Johnson L, Muhammad IF, Persson M, Niu K, Engstrom G. Comparing the inflammatory profiles for incidence of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases: a prospective study exploring the ‘common soil’ hypothesis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:87.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300.

Ruparelia N, Chai JT, Fisher EA, Choudhury RP. Inflammatory processes in cardiovascular disease: a route to targeted therapies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:314.

Schutyser E, Struyf S, Van Damme J. The CC chemokine CCL20 and its receptor CCR39. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:409–26.

Slyepchenko A, Maes M, Kohler CA, Anderson G, Quevedo J, Alves GS, Berk M, Fernandes BS, Carvalho AF. T helper 17 cells may drive neuroprogression in major depressive disorder: proposal of an integrative model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;64:83–100.

Poletti S, de Wit H, Mazza E, Wijkhuijs AJM, Locatelli C, Aggio V, Colombo C, Benedetti F, Drexhage HA. Th17 cells correlate positively to the structural and functional integrity of the brain in bipolar depression and healthy controls. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;61:317–25.

Hirota K, Yoshitomi H, Hashimoto M, Maeda S, Teradaira S, Sugimoto N, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ito H, Nakamura T, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S. Preferential recruitment of CCR42-expressing Th17 cells to inflamed joints via CCL20 in rheumatoid arthritis and its animal model. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2803–12.

Yamazaki T, Yang XO, Chung Y, Fukunaga A, Nurieva R, Pappu B, Martin-Orozco N, Kang HS, Ma L, Panopoulos AD, Craig S, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. CCR43 regulates the migration of inflammatory and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:8391–401.

Reboldi A, Coisne C, Baumjohann D, Benvenuto F, Bottinelli D, Lira S, Uccelli A, Lanzavecchia A, Engelhardt B, Sallusto F. C–C chemokine receptor 6-regulated entry of TH-17 cells into the CNS through the choroid plexus is required for the initiation of EAE. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:514–23.

Axtell RC, Steinman L. Gaining entry to an uninflamed brain. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:453–5.

Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Bot M, Drent ML, Penninx BW. Leptin dysregulation is specifically associated with major depression with atypical features: evidence for a mechanism connecting obesity and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:807–14.

Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Peyrot WJ, Baune BT, Breen G, Dehghan A, Forstner AJ, Grabe HJ, Homuth G, Kan C, Lewis C, Mullins N, Nauck M, Pistis G, Preisig M, Rivera M, Rietschel M, Streit F, Strohmaier J, Teumer A, Van der Auwera S, Wray NR, Boomsma DI, Penninx B. Genetic association of major depression with atypical features and obesity-related immunometabolic dysregulations. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:1214–25.

Nixon Andreasson A, Jernelov S, Szulkin R, Unden AL, Brismar K, Lekander M. Associations between leptin and self-rated health in men and women. Gend Med. 2010;7:261–9.

Andreasson AN, Carlsson AC, Wandell PE. High levels of leptin are associated with poor self-rated health in men and women with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:e11–2.

Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, Friedman JM. Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science. 1995;269:543–6.

Myers MG, Cowley MA, Munzberg H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:537–56.

Martin SS, Qasim A, Reilly MP. Leptin resistance: a possible interface of inflammation and metabolism in obesity-related cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1201–10.

Milaneschi Y, Simmons WK, van Rossum EFC, Penninx BW. Depression and obesity: evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:18–33.

Guo M, Huang TY, Garza JC, Chua SC, Lu XY. Selective deletion of leptin receptors in adult hippocampus induces depression-related behaviours. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:857–67.

Guo M, Lu XY. Leptin receptor deficiency confers resistance to behavioral effects of fluoxetine and desipramine via separable substrates. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e486.

Lu XY. The leptin hypothesis of depression: a potential link between mood disorders and obesity? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:648–52.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge support of the Clinical biomarker facility at SciLifeLab Sweden for providing assistance in protein analyses.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation (Grant No. 2016-0315 and 2017-0626), the Region Skåne County Council, and the China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 201808320331).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XB and GE designed the study. XB and GE developed the methodology. XB performed the statistical analysis. XB, YB, SY, KN, MOM, JN, OM and GE contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. XB wrote the manuscript. XB, YB, SY, KN, MOM, JN, OM and GE reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden (LU 51/90) and was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent have been obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, X., Borné, Y., Yin, S. et al. The associations of self-rated health with cardiovascular risk proteins: a proteomics approach. Clin Proteom 16, 40 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-019-9258-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-019-9258-9