Abstract

The cyclic treatment technique (redox cycling) comprising stages of material exposition in reducing and oxidizing high-temperature environments and intermediate degassing between these stages has been developed to improve the structural integrity of YSZ–NiO ceramic anode substrates for solid oxide fuel cells. A series of specimens were singly reduced in a hydrogenous environment (the Ar–5 vol% Н2 mixture or hydrogen of 99.99 vol% H2 purity) under the pressure of 0.15 MPa or subjected to redox cycling at 600 or 800 °C. The influence of redox cycling at the treatment temperatures of 600 and 800 °C on the structure, strength and electrical conductivity of the material has been analysed. Using the treatment temperature 600 °C, a structure providing improved physical and mechanical properties of the material was formed. However, at the treatment temperature 800 °C, an anode structure with an array of microcracks was formed that significantly reduced the strength and electrical conductivity of the material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A number of publications predict a dual influence of operating temperature on resulting physical and mechanical properties of the Ni-containing anode material for solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) after cyclic reduction–oxidation (redox) treatment [1–3]. It is well known that the electrical conductivity of metallic Ni (of about 1.4 · 107 S/m) is much higher than that of YSZ–Ni cermet. According to our data, after exposition of the ceramics sintered of NiO powder, for 4 h or more in pure hydrogen at 600 °C, complete reduction can be achieved [4]. The resulting electrical conductivity of the material is about (1–5) · 106 S/m. However, exposition of NiO ceramics at this regime in the Ar–5 vol% Н2 mixture that can be used for gradual reduction of SOFC anodes causes partial reduction of the NiO particles forming thin edgings of metallic Ni (of thickness of 0.1–0.3 μm) around them. Thus, the electrical conductivity of the material treated is in the range of (1–5) · 105 S/m depending on average particle size, porosity and resulting contacts between Ni edgings. During redox treatment of NiO ceramics, structural transformation of boundaries of contacting nickel phase particles occurs, causing an increase in strength.

In our previous works, it was revealed for ScCeSZ–NiO anode ceramics that at selected redox treatment regimes when the material is heated in vacuum and intermediate degassing between reduction and oxidation stages is performed, substantial improvements in strength (up to 112 %) and electrical conductivity can be reached at the treatment temperature of 600 °C [5, 6].

The aims of this work are to study the physical and mechanical behaviour of the SOFC anode material during the cyclic redox treatment depending on the treatment temperature and also to find out the microstructural changes causing resulting properties of the material.

Review

Experimental

Anode ceramics of the YSZ–NiO system sintered at Forschungszentrum Jülich (Germany) of zirconium oxide powder stabilized with 8 mol% Y2O3, with the addition of 50 wt% NiO, has been investigated. A series of specimens of the size of 1 × 5 × 25 mm were singly reduced at 600 or 800 °C in a hydrogenous environment (the Ar–5 vol% Н2 mixture or hydrogen of 99.99 vol% H2 purity) under the pressure of 0.15 MPa (Fig. 1a) or subjected to redox cycling (see Table 1). The redox treatment of ceramics was performed for five cycles according to the scheme [4]: heating in vacuum from 20 to 600 °C, reduction in a hydrogenous environment at 600 or 800 °C under the pressure of 0.15 MPa, degassing, oxidation in air at 600 °C and cooling down to 20 °С in air (Fig. 1b). Reduction/oxidation stage duration was chosen, taking into account the literature data on complete or partial reduction of the material [7]. After the redox cycling, reduction of materials in a hydrogenous environment for 4 h at 600 °C or for 1 h at 800 °C under the pressure of 0.15 MPa with cooling in argon was performed (see the scheme in Fig. 1a). The heating/cooling rate was 20 °C/min.

Ultimate fracture stresses of materials in the initial state (σ f0) and after the corresponding treatment (σ f) were determined during the three-point bending test of the specimens in air at 20 °C. Based on these data, the relative strength (σ f / σ f0) of the material treated was evaluated.

The specific electrical conductivity of the material (σ) was determined in air at 20 °C using the Van der Pauw method. SEM microstructures and microfractographs of the specimens were investigated using the electron microscope Carl Zeiss EVO-40XVP.

The X-ray analysis was carried out using an X-ray diffractometer (Cu Кα) with Bragg–Brentano-type geometry. The average size of coherent dispersion areas of nickel phase (D) was calculated using the Win CSD program [8].

The spacing between the planes in the atomic lattice (d) of zirconia phase (line 220) was estimated using the Rietveld method [8], and the residual stresses (σ r) were evaluated using the equation

where E is Young’s modulus and ν is Poisson’s ratio; the values of these parameters were selected according to [9]; d 0 is the spacing between the planes in the atomic lattice of zirconia phase (line 220) for the as-received material.

Thermodynamics of reactions of nickel phase reduction and oxidation was analysed by calculating the changes in Gibbs’ free energy (ΔG) using standard data [10].

Results and Discussion

Thermodynamics of the Reduction and Oxidation Stages

It is known [11] that in the temperature range 630–680 °C, a transition from diffusion to kinetic mechanism of oxidation occurs. Additionally, by analysing the thermodynamics of reduction and oxidation stages, it was revealed that in the temperature range 600–800 °C, the change in Gibbs’ free energy (ΔG) is more negative and the equilibrium constant (К) is considerably higher for the reaction of nickel oxidation compared to its reduction (see Table 2). According to this, we concluded that during redox cycling at higher temperature, the Ni oxidation stage becomes more faster than the NiO reduction one. Thus, the probability of retaining unreduced particles is high, if the reduction period was too short. In such a case, the resulting structure does not meet the requirements on uniformity and, finally, efficiency of an anode substrate.

The Treatment Temperature of 600 °C

Exposition of YSZ–NiO ceramics at the temperature 600 °C for 4 h in the Ar–5 vol% H2 mixture that can be used for gradual reduction of SOFC anodes (version 1 in Table 1) causes partial reduction of the NiO particles by a diffusion mechanism. Thin Ni edgings (of thickness of 0.1–0.3 μm) are formed around NiO particles (Fig. 2а).

SEM microstructures (a, c, e, g) and microfractographs (b, d, f, h) for the material in versions 1 (a, b), 2 (c, d), 3 (e, f) and 4 (g, h) (see Table 1)

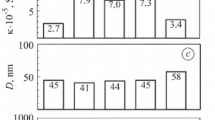

The substructure of these edgings was evaluated using X-ray data on average size of coherent dispersion areas of nickel phase (D) (Fig. 3(а)). This parameter was measured as 45 nm.

Average size of coherent dispersion area (D) (a), residual stresses (σ r), in zirconia phase (b), relative strength (σ f / σ f0) (c) and specific electrical conductivity (σ) (d) for the material in versions 1–6 (see Table 1). The numbers on the bars indicate the values of corresponding parameters

Reduction in strength to 84 % of the value for the as-received YSZ–NiO ceramics (Fig. 3(c)) is possibly caused by partial structural transformation of nickel phase followed by a little volume decrease. It is displayed in the mixed fracture micromechanism (Fig. 2b). Although, no noticeable change of zirconia skeleton was found for this variant of the treatment. As compared to the as-received material, residual stresses did not change as well (Fig. 3(b)). The electrical conductivity of the material of 2.7 · 105 S/m is provided by thin films of Ni around NiO particles united into the network (Fig. 3(d)).

More intensive reduction of YSZ–NiO ceramics by the same diffusion mechanism occurs in pure hydrogen (version 2 in Table 1). During 4 h, the structure of completely reduced Ni particles is formed (Fig. 2c). The substructure parameter (average size D) of these particles was measured as 41 nm that is less than for version 1 (Fig. 3(а)). Simultaneously, the volume decrease of initial NiO particles of 41.6 % occurs [12]. Nanopores on Ni particles formed due to their shrinkage as well as the pores between the particles prevent the rise of residual tensile stresses (Fig. 3(b)). Nickel phase transformation followed by volume change and formation of pores causes the loss of a significant percentage of particle bonds and violate material integrity which is displayed in the predominantly intergranular fracture micromechanism (Fig. 2d). Reduction in strength to 48 % of the value for the as-received YSZ–NiO ceramics is recognized (Fig. 3(c)). Thanks to complete reduction of nickel phase, the high electrical conductivity (Fig. 3(d)) of the material is achieved compared to the similar functional materials [13].

According to our data [4], there exists a substantial difference in the mechanical behaviour of NiO ceramics after redox treatment as compared to that of the singly reduced material, at the treatment temperature of 600 °C. During the treatment, structural transformation of boundaries of contacting nickel phase particles occurs, causing an increase in strength.

The cleavage fracture micromechanism was noted in the specimens tested. This micromechanism corresponds to the higher cohesive strength of nickel phase particles as compared to the ultimate cleavage stress of the particles themselves.

Such treatment technique has been used in this work for improvement of strength and electrical conductivity of YSZ–NiO ceramics. Upon redox cycling, exposition of the material at the temperature 600 °C for 4 h in air resulted in complete oxidation of preliminarily reduced Ni edgings on NiO particles (version 3 in Table 1, Fig. 2e) as well as of preliminarily reduced Ni particles (version 4, Fig. 2g) by diffusion mechanism. After five cycles of the redox treatment at 600 °C with final reduction stage (version 3), most of NiO particles were reduced completely, forming a continuous network of electrically conducting material in the zirconia skeleton (Fig. 2e) which resulted in the value of specific electrical conductivity of the material of 7 · 105 S/m (Fig. 3(d)). Fragmentation of coarse grains of nickel phase resulted in more fine structure of the material treated. The substructure parameter (D) of reduced particles for version 3 was measured as 44 nm which is similar to that for version 1 (Fig. 3(а)). Thus, no distinct change of substructure of nickel particles was found.

The X-ray data displayed a reduction of 2Θ angle for cyclically treated materials. In accordance with Wolf–Bragg’s law

where n is the positive integer and λ is the wavelength of incident wave; the spacing between the planes in the atomic lattice (d) of zirconia phase increases resulting (see Eq. (1)) in considerable relaxation of residual stresses (σ r) in the material of versions 3 and 4 as compared to the as-received material (Fig. 3(b)). This affects positively the mechanical behaviour of the material, especially of version 3 (Fig. 3(c)).

The mixed fracture micromechanism was noted in tested specimens of versions 3 (Fig. 2f) and 4 (Fig. 2h). The fracture surfaces comprise brittle cleavage areas of ceramic matrix neighbouring to ductile fracture ones of reduced nickel (Fig. 2f). Like for the NiO ceramics treated [4], this corresponds to higher cohesive strength between the particles of zirconia and nickel phase as compared to the singly reduced material.

The Treatment Temperature of 800 °C

In order to reduce the redox treatment duration, the behaviour of YSZ–NiO ceramics was estimated under redox cycling at 800 °C. During single exposition of the material in the Ar–5 vol% H2 mixture at this temperature (version 5 in Table 1), NiO particles are reduced completely within 1 h (Fig. 4а) by diffusion mechanism of much higher intensity as compared to version 1. Reduced Ni particles are dotted with nanopores. The NiO to Ni transformation is carried out rapidly with formation of comparatively coarse substructure (parameter D of reduced particles was measured as 64 nm, see Fig. 3(a)).

SEM microstructure (a) and microfractograph (b) for the material in version 5 (see Table 1)

The X-ray data display the increase of the 2Θ angle for the material singly reduced at 800 °C. Consequently, the spacing between the planes in the atomic lattice (d) of the zirconia phase decreases, resulting in considerable growth of residual stresses (σ r) in the material of version 5 as compared to the as-received material (Fig. 3(b)).

The singly reduced material has somewhat lower strength as compared to as-received ceramics (Fig. 3(c), version 5) but substantially higher electrical conductivity as compared to the material treated at 600 °C (Fig. 3(d), versions 5 and 1, respectively). The mixed fracture micromechanism is recognized in the specimens tested (Fig. 4b). It is similar to the one after the redox treatment of YSZ–NiO ceramics at 600 °C. It also evidences that single reduction at 800 °C does not violate the integrity of the zirconia skeleton and a partial decrease in strength is caused by nickel phase transformation.

Contrary to the positive effect of redox treatment of YSZ–NiO ceramics at 600 °C, a negative tendency for strength of YSZ–NiO ceramics during the treatment at 800 °C is noted (Fig. 3(c), version 6). In both cases of the treatment of YSZ–NiO ceramics, the resulting structures are similar (Fig. 5a as compared to Fig. 2e) except for the peculiar (of green colour) inner part of specimens after the treatment at 800 °C (Fig. 5d). As stated above, a kinetic mechanism of oxidation at this temperature intensifies the growth of unreduced volume of the anode during redox cycling.

SEM microstructure (a) and microfractographs (b–d) for the material in version 6 (see Table 1)

Two different areas on the fracture surface picture of a specimen treated at 800 °C are observed. In the reduced layer, mixed fracture micromechanism comprising transgranular cleavage of zirconia particles and intergranular fracture along the boundaries of contacting nickel phase particles dominates (Fig. 5b). The nickel particles of smaller sizes had possibly agglomerated on zirconia particles. Being intact, they are separated by a network of the pores formed during the redox treatment. Thus, this fracture micromechanism is as energy expensive as the one revealed for the material after the redox treatment at 600 °C (Fig. 2f).

In the unreduced inner layer of the anode transgranular cleavage, a fracture of coarse zirconia and nickel oxide agglomerates dominates, and occasionally, the signs of intergranular fracture along the boundaries of particles of smaller size are observed (Fig. 5c).

In spite of similar levels of residual stresses in the zirconia phase that were estimated for the entire reduced volume (Fig. 3(b), version 5) and outer reduced layer (version 6), respectively, different structural factors affect the integrity of these materials.

The total strength of the material after redox treatment at 800 °C is decreased considerably with the array of microcracks in the bulk of the specimen (Fig. 5d) that have formed during the treatment normally to its surface. These microcracks are nucleated following a stress gradient on the boundaries between reduced and unreduced layers as a result of thermal expansion (thermal expansion coefficients for YSZ, NiO and Ni phases are 10.9 · 10−6, 14.1 · 10−6 and 16.4 · 10−6/K, respectively [14]). The reduced layer showed the value of specific electrical conductivity 3.4 · 105 S/m (Fig. 3(d), version 6) which is satisfactory for SOFC anodes. However, this value is lower than that of the material singly reduced at 800 °C (version 5). Beside, the unreduced layer having very low electrical conductivity becomes a substantial obstacle in achieving the required electrochemical performance of the fuel cell.

Thus, contrary to the positive effect of redox treatment at 600 °C on strength and electrical conductivity of YSZ–NiO ceramics, such treatment at 800 °C causes the formation of anode structure with reduced outer and unreduced inner layers as well as the array of microcracks in the bulk of an anode initiated normally to its surface, what causes the loss of its integrity. The unreduced inner layer of the anode has unsatisfactory electrical conductivity.

Conclusions

A cyclic treatment technique (redox cycling) comprising stages of material exposition in reducing and oxidizing high-temperature gas environments and intermediate degassing between these stages has been developed to improve the strength and electrical conductivity of YSZ–NiO ceramic anode substrates for solid oxide fuel cells. Based on the experimental data, we suppose that redox cycling at 600 °C is the most ideal for this material. The parameters of the treatment (reduction dwell time not less than 4 h under the pressure of the Ar–5 vol% H2 mixture of 0.15 MPa; oxidation dwell time 4 h) allow a structure to be formed which provides improved physical and mechanical properties of the material. In such a structure, according to the X-ray analysis, a substantial drop of residual stresses is achieved as compared to the one-time reduced material.

References

Sarantaridis D, Atkinson A (2007) Redox cycling of Ni-based solid oxide fuel cell anodes: a review. Fuel Cells 3:246–258

Ettler M, Timmermann H, Malzbender J et al (2010) Durability of Ni anodes during reoxidation cycles. J Power Sources 195:5452–5467

Wood A, Waldbillig D (2011) Preconditioning treatment to enhance redox tolerance of solid oxide fuel cells., US Patent 8,029,946 B2, 4 Oct 2011

Podhurs’ka VY, Vasyliv BD, Ostash OP et al (2014) Structural transformations in the NiO-containing anode of ceramic fuel cells in the course of its reduction and oxidation. Materials Sci 49(6):805–811

Ostash OP, Vasyliv BD, Podhurs’ka VY et al (2011) Optimization of the properties of 10Sc1CeSZ–NiO composite by the redox treatment. Materials Sci 46(5):653–658

Vasyliv BD, Podhurs’ka VY, Ostash OP et al (2013) Influence of reducing and oxidizing media on the physicomechanical properties of ScCeSZ–NiO and YSZ–NiO ceramics. Materials Sci 49(2):135–144

Tikekar N, Armstrong T, Virkar A (2006) Reduction and reoxidation kinetics of Ni-based SOFC anodes. J Electrochem Soc 153:A654–A663

Akselrud LG, Zavalii PY, Grin YN et al (1993) Use of the CSD program package for structure determination from powder data. Mat Sci Forum 133:335–342. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.133-136.335

Sun B, Rudkin RA, Atkinson A (2009) Effect of thermal cycling on residual stress and curvature of anode-supported SOFCs. Fuel Cells 6:805–813

Mills I, Cvitas T, Homann K et al (1993) Quantities, units and symbols in physical chemistry. Blackwell, London

Peraldi R, Monceau D, Pieraggi B (2002) Correlations between growth kinetics and microstructure for scales formed by high-temperature oxidation of pure nickel. I. Morphologies and microstructures. Oxid Met 58:249–273

Faes A, Nakajo A, Hessler-Wyser A et al (2009) Redox study of anode-supported solid oxide fuel cell. J Power Sources 193:55–64

Zhang Y, Liu B, Tu B et al (2005) Redox cycling of Ni–YSZ anode investigated by TRP technique. Solid State Ion 176:2193–2199

Mori M, Yamamoto T, Itoh H et al (1998) Thermal expansion of nickel-zirconia anodes in solid oxide fuel cells during fabrication and operation. J Electrochem Soc 145:1374–1381

Acknowledgements

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

VP performed the electrical conductivity tests and microstructural and fractography studies; constructed Figs. 1a, b and 3; and contributed to the sections ‘Experimental’ and ‘Results and Discussion’ (including the subsections ‘Thermodynamics of the Reduction and Oxidation Stages’ and ‘The Treatment Temperature of 600 °C’) and the ‘References’. BV performed the mechanical tests and microstructural and fractography studies; constructed Figs. 2, 4 and 5; and contributed to the sections ‘Experimental’ and ‘Results and Discussion’ (including the subsections ‘The Treatment Temperature of 600 °C’ and ‘The Treatment Temperature of 800 °C’) and the ‘References’. OO analysed the literature data and test results and contributed to the sections ‘Introduction’, ‘Results and Discussion’ (including the subsections ‘The Treatment Temperature of 600 °C’ and ‘The Treatment Temperature of 800 °C’) and ‘Conclusions’ as well as the ‘References’. YB contributed to the sections ‘Experimental’ and ‘Results and Discussion’ (including the subsection ‘Thermodynamics of the Reduction and Oxidation Stages’) and the ‘References’. OV analysed the literature data and test results and contributed to the sections ‘Introduction’, ‘Results and Discussion’ (including the subsection ‘Thermodynamics of the Reduction and Oxidation Stages’) and ‘Conclusions’ as well as the ‘References’.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Podhurska, V., Vasyliv, B., Ostash, O. et al. Influence of Treatment Temperature on Microstructure and Properties of YSZ–NiO Anode Materials. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 93 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1306-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1306-z