Abstract

Background

New treatments are currently offering new opportunities and challenges in clinical management and research in the migraine field. There is the need of homogenous criteria to identify candidates for treatment escalation as well as of reliable criteria to identify refractoriness to treatment. To overcome those issues, the European Headache Federation (EHF) issued a Consensus document to propose criteria to approach difficult-to-treat migraine patients in a standardized way. The Consensus proposed well-defined criteria for resistant migraine (i.e., patients who do not respond to some treatment but who have residual therapeutic opportunities) and refractory migraine (i.e., patients who still have debilitating migraine despite maximal treatment efforts).

The aim of this study was to better understand the perceived impact of resistant and refractory migraine and the attitude of physicians involved in migraine care toward those conditions.

Methods

We conducted a web-questionnaire-based cross-sectional international study involving physicians with interest in headache care.

Results

There were 277 questionnaires available for analysis. A relevant proportion of participants reported that patients with resistant and refractory migraine were frequently seen in their clinical practice (49.5% for resistant and 28.9% for refractory migraine); percentages were higher when considering only those working in specialized headache centers (75% and 46% respectively). However, many physicians reported low or moderate confidence in managing resistant (8.1% and 43.3%, respectively) and refractory (20.7% and 48.4%, respectively) migraine patients; confidence in treating resistant and refractory migraine patients was different according to the level of care and to the number of patients visited per week. Patients with resistant and refractory migraine were infrequently referred to more specialized centers (12% and 19%, respectively); also in this case, figures were different according to the level of care.

Conclusions

This report highlights the clinical relevance of difficult-to-treat migraine and the presence of unmet needs in this field. There is the need of more evidence regarding the management of those patients and clear guidance referring to the organization of care and available opportunities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

New migraine treatments, both acute and preventative, such as lasmiditan, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) pathway, and gepants are changing the landscape of migraine treatment offering new opportunities and challenges [1,2,3,4,5]. Those treatments raised the issue of appropriate selection of patients because their direct cost is higher than the conventional medications [6]. Additionally, despite having a high responder rate, a proportion of patients still do not respond according to conventionally accepted definitions [7,8,9,10]. A recent real-life observational study found that 38% of patients who failed all available preventatives were non-responders after 6 months of treatment to one CGRP targeting monoclonal antibody (erenumab) [11].

In order to move forward in the field of difficult-to-treat migraine patients, the European Headache Federation (EHF) with the endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance (EMHA) issued a Consensus document to propose criteria to approach those patients [12]. In details, the new definitions of the difficult to treat migraine included non-response to acute and preventative medications. So, two diagnostic categories were identified, i.e., resistant and refractory migraine. First, 8 days with debilitating migraine despite intake acute antimigraine medication was defined as the threshold. Further, patients who tried three different classes of migraine preventative and still suffer eight debilitating migraine days classify for resistant migraine. In order to be defined as refractory, failure to all available classes of migraine preventatives, including mAbs targeting the CGRP pathway, is required.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to better understand the clinical reality and the attitude of physicians involved in migraine care toward these patients.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

We conducted a web-questionnaire-based cross-sectional international study involving headache physicians. All physicians involved in the care of patients with headache, without any restriction referring to country of residency, specialization, and years of experience in headache care were entitled to fill the questionnaire.

The e-questionnaire was shared at the 2020 annual EHF virtual conference and by advertisement on social media. Additionally, the questionnaire was publicized by mailing lists and national websites by the national headache societies affiliated to the EHF. Sharing was started in July 2020 and the data base was locked on 03 October 2020.

Instruments and data collection

The e-questionnaire was developed by discussion and consensus within the study panel (Supplement 1). The questionnaire was built online using Redcap®, a software for designing research databases [13].

Before starting to fill-out the questionnaire participants were provided with a figure summarizing the definitions of resistant and refractory migraine and with the link to the published Consensus article [12].

Each participant had to report gender, specialization, years of experience in headache medicine, the work setting and the number of patients visited per week.

Work settings categories were defined, according to EHF definitions of the level of care [14], as follows: 1) first level of care - General primary care defined as first-line headache service (accessible first contact for most people with headache); 2) second level of care - Special-interest headache care defined as ambulatory care delivered by physicians with a special interest in headache; 3) third level of care - Headache Specialists Centers defined as advanced multidisciplinary care delivered by headache specialists in hospital-based centers. These definitions [14] were also provided as a part of the e-questionnaire.

Data protection, sharing, and ethics

The questionnaire was not anonymous, and participants were requested to provide consent to be listed as contributors to the study. Guarantee was provided referring to the use of the provided information only in aggregated forms and not at an individual level. Group authorship was granted to all those completing the questionnaire (Burden and Attitude to Resistant and Refractory [BARR] Study Group).

As the study did not involve use data from single patients, we did not ask for an Ethic Committee approval. The data base of this study is stored at the University of L’Aquila and is available upon reasonable request form authorities and researchers by contacting the corresponding author.

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics and provided distributions of the responses to selected questions. Chi-squared test was performed to compare frequencies among variables of interest. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics 21.0.

Results

The present paper is based on questionnaires filled by 277 physicians (n = 133; 48.0% female); 15 questionnaires were discarded because they were incomplete. Distribution by country is reported in Fig. 1. Characteristics of participants according to years of practice in headache medicine, specialty, and work setting are reported in Table 1.

Resistant migraine was frequently encountered in clinical practice. Overall, 137/277 (49.5%) participants reported that they manage very frequently patients with resistant migraine, 100 (36.1%) participants reported that they manage occasionally those patients, and 40 (14.4%) reported that they manage rarely those patients. Those percentages were significantly different among the three possible levels of care (P < 0.0001). In fact, in headache specialist centers, 75% of physicians reported that they manage very frequently patients with resistant migraine; the corresponding proportion was 48% for special interest headache care and 13% for general primary care/neurology (Fig. 2).

Refractory migraine was as well a condition frequently encountered in clinical practice. Overall, 80/277 (28.9%) participants reported that they manage very frequently patients with refractory migraine, 110 (39.7%) reported that they manage occasionally those patients, and 86 (31.0%) reported that they manage rarely those patients. These percentages were significantly different among the different levels of care (P < 0.0001). In fact, in headache specialist centers, 46% of physicians reported that they manage very frequently patients with refractory migraine the corresponding proportion was 23% for special interest headache care and 8% for general primary care/neurology (Fig. 2).

Overall, 22 (8.1%) respondents reported low, 117 (43.3%) moderate, and 131 (48.5%) high confidence in treating resistant migraine, while 57 (20.7%) reported low, 133 (48.4%) moderate, and 85 (30.9%) high confidence in treating refractory migraine As shown in Fig. 3, confidence in treating patients with resistant and refractory migraine was different according to the level of care (P < 0.001 and P = 0.006, respectively), to the number of migraine patients visited per week (P < 0.001 for both), to the years in headache medicine after graduation of the treating physician (P < 0.001 for both), and to the frequency of resistant/refractory migraine patients visited (P < 0.001 for both).

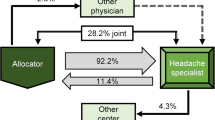

Overall, 245/277 (88.4%) respondents reported that patients with resistant migraine were treated in their own center, while 32 (11.6%) reported that patients were referred to a more specialized center. The corresponding data were 224 (80.9%) and 52 (18.8%) respectively for refractory migraine. Figures were significantly different according to the level of care (P < 0.001 for both resistant and refractory), as reported in Fig. 4.

Referring to the ideal setting of care, 22 (6%) respondents considered that resistant migraine should be managed in general primary care, 162 (43%) in special interest headache care, and 191 (51%) in specialized headache centers. The corresponding figures for refractory migraine were 19 (6%), 95 (28%) and 230 (67%) respectively (Fig. 5).

Discussion

As new treatment opportunities are entering the migraine filed, new challenges are faced by those who are involved in migraine care and research [15,16,17]. First, there is the need of reliable criteria, both in clinical practice and in research settings, to select homogenous populations of migraine patients who require treatment escalation. This would ensure a more standardized clinical management of patients and research results’ comparability. Second, while in the past mostly passive acceptance of the lack of successful treatment for some patients with migraine was registered, nowadays researchers are looking for novel migraine specific therapeutic targets. The study of patients who do not have adequate response to the available migraine treatments may provide not only more therapeutic opportunities, but also may improve our understanding in the mechanisms underlying migraine in general.

The present study reports a summary of the impact and attitude toward resistant and refractory migraine. Our data showed that both resistant and refractory migraine are commonly and globally faced in the headache care. Resistant and refractory migraine are particularly common in tertiary level headache centers, where 75% and 46%, respectively, of the physicians use to see very frequently those patients. However, despite being relatively common, many physicians reported a sub-optimal confidence in managing those patients. Remarkably, even in tertiary level headache centers, only 39% of physicians reported high confidence in managing patients with refractory migraine. The figure may be attributed by lack of knowledge of the definition, lack of additional treatment possibilities and lack of guidelines which may help to support those patients. However, physicians with more experience (i.e., more patients visited per week and more years in practice) reported more often a high confidence in treating both resistant and refractory migraine, further highlighting the lack of standardized guidelines and the consequent physicians’ trend to mainly rely on their expertise.

Surprisingly, we found a low referral to more advanced levels of care for patients with resistant and refractory migraine, despite a relevant proportion of physicians operating in the two more basic levels of care expressed from low to moderate confidence in treating those patients. On the other hand, around half of the participants considered that tertiary level headache care is the ideal setting for resistant migraine and 2/3 of participants considered that tertiary level headache care is the ideal setting for refractory migraine.

This preliminary report provides a gross understanding of resistant and refractory migraine, however with some limitations. Responses were based on perceptions and opinions of the participants and bias and inaccuracy. Additionally, generalizability of the findings can be limited. In fact, there were many countries (among them United States and Canada) with lack of responders; the distribution of responders was not homogenous across countries. Due to the limited number of participants per country, we could not perform country-specific analyses. Additionally, also availability of new migraine drugs and the system of care are variable across countries, and this may reflect different attitudes which were not examined by our study. An upcoming filed testing and real-life prospective international study in headache centers across Europe (A real-life study on Resistant and rEFractory migraINE [REFINE]) will provide more insights on the validity of the proposed definitions as well as on the characteristics and clinical course of patients who meet the definition criteria for resistant and refractory migraine.

Conclusions

Resistant and refractory migraine are conditions which are perceived as common in the clinical practice of those involved in the care of patients with migraine and working in dedicated headache care or centers. Despite being common, there is a lot of uncertainty from physicians, pointing out the need of support. It would be important to set up organized systems for referral of the difficult-to-treat patients from general primary care/neurology and eventually from special interest headache care to tertiary headache centers and to provide guidance on migraine care in situations where the positive clinical response if difficult to achieve. Further research is also needed to clarify the mechanisms which contribute to drug refractoriness in migraine, to understand the role of comorbidities and the therapeutic opportunities arising from combination drugs. Moreover, underlying mechanisms in migraine are far from being entirely clear and there hope that the ongoing future research may shade light on novel targets which may allow the development of new drugs.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- EHF:

-

European Headache Federation

- EMHA:

-

European Migraine & Headache Alliance

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- mAbs:

-

Monoclonal antibodies

References

De Matteis E, Guglielmetti M, Ornello R, Spuntarelli V, Martelletti P, Sacco S (2020) Targeting CGRP for migraine treatment: mechanisms, antibodies, small molecules, perspectives. Expert Rev Neurother 20(6):627–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1772758

Negro A, Sciattella P, Rossi D, Guglielmetti M, Martelletti P, Mennini FS (2019) Cost of chronic and episodic migraine patients in continuous treatment for two years in a tertiary level headache Centre. J Headache Pain 20(1):120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1068-y

Mecklenburg J, Raffaelli B, Neeb L, Sanchez Del Rio M, Reuter U (2020) The potential of lasmiditan in migraine. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 13:1756286420967847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756286420967847

Raffaelli B, Neeb L, Reuter U (2019) Monoclonal antibodies for the prevention of migraine. Expert Opin Biol Ther 19(12):1307–1317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2019.1671350

Tiseo C, Ornello R, Pistoia F, Sacco S (2019) How to integrate monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide or its receptor in daily clinical practice. J Headache Pain 20(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1000-5

Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, Reuter U, Terwindt G, Mitsikostas DD, Martelletti P (2019) European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain 20(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0955-y

Ornello R, Casalena A, Frattale I, Gabriele A, Affaitati G, Giamberardino MA, Assetta M, Maddestra M, Marzoli F, Viola S, Cerone D, Marini C, Pistoia F, Sacco S (2020) Real-life data on the efficacy and safety of erenumab in the Abruzzo region, central Italy. J Headache Pain 21(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01102-9

Raffaelli B, Kalantzis R, Mecklenburg J, Overeem LH, Neeb L, Gendolla A et al (2020) Erenumab in chronic migraine patients who previously failed five first-line oral prophylactics and OnabotulinumtoxinA: a dual-center retrospective observational study. Front Neurol 11:417. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00417

Russo A, Silvestro M, Scotto di Clemente F, Trojsi F, Bisecco A, Bonavita S et al (2020) Multidimensional assessment of the effects of erenumab in chronic migraine patients with previous unsuccessful preventive treatments: a comprehensive real-world experience. J Headache Pain 21(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01143-0

Scheffler A, Messel O, Wurthmann S, Nsaka M, Kleinschnitz C, Glas M, Naegel S, Holle D (2020) Erenumab in highly therapy-refractory migraine patients: first German real-world evidence. J Headache Pain 21(1):84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01151-0

Lambru G, Hill B, Murphy M, Tylova I, Andreou AP (2020) A prospective real-world analysis of erenumab in refractory chronic migraine. J Headache Pain 21(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01127-0

Sacco S, Braschinsky M, Ducros A, Lampl C, Little P, van den Brink AM, Pozo-Rosich P, Reuter U, de la Torre ER, Sanchez del Rio M, Sinclair AJ, Katsarava Z, Martelletti P (2020) European headache federation consensus on the definition of resistant and refractory migraine : developed with the endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance (EMHA). J Headache Pain 21(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01130-5

REDCap. Available from: https://projectredcap.org/software/. Accessed 10 Mar 2021.

Steiner TJ, Antonaci F, Jensen R, Lainez MJ, Lanteri-Minet M, Valade D (2011) Recommendations for headache service organisation and delivery in Europe. J Headache Pain 12(4):419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-011-0320-x

Martelletti P, Edvinsson L, Ashina M (2019) Shaping the future of migraine targeting calcitonin-gene-related-peptide with the disease-modifying migraine drugs (DMMDs). J Headache Pain 20(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1009-9

Martelletti P, Ashina M, Edvinsson L (2019) The changing faces of migraine. J Headache Pain 20(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1006-z

Do TP, Guo S, Ashina M (2019) Therapeutic novelties in migraine: new drugs, new hope? J Headache Pain 20(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-0974-3

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Burden and Attitude to Resistant and Refractory (BARR) Study Group:

Albania: Genci Cakciri, Pavllo Djamandi, Serla Grabova, Gleni Halili, Jera Kruja, Altin Kuqo, Diana Naco, Aida Quka, Ladjola Stefanidhi, Gentian Vyshka, Ilirjana Zekja. Argentina: Osvaldo Bruera, Dilver Gómez, Brenda Guitian, Juan Carlos Roma. Australia: Ike Leon Chen. Austria: Christian Lampl. Azerbaijan: Samira Bashirova. Belarus: Maxim Linkov. Belgium: Daan Van Den Abbeele, Geraldine Vanderschueren. Brasil: Roberta Araujo, Renato Arruda, Antônio Catharino, Jovana Ciriaco, Amauri Dalla Corte, Ricardo Dornas, Bernardo Felsenfeld Jr., André Fonseca Taufner, Yara Fragoso, Rubens Hurtado, Daniel Isoni Martins, Renata Londero, Luciano Melo, Kelton Stivenson Mignoni, Paulo Victor Sgobbi De Souza, Marcio Nattan Souza. Bulgaria: Sevdzhan Osman. Chile: Veronika Baltzer. Colombia: Luis Fabian Pacheco Mosquera. Croatia: Ivan Dubroja, Zlatko Hucika, Marijana Lisak, Arijana Lovrencic-Huzjan, Ivo Lušić, Darija Mahovic Lakusic. Czech Republic: Petr Mikulenka, Pavel Řehulka. Denmark: Faisal Mohammad Amin, Sonja Antic, Zainab Fakhril-Din, Jakob Moeller-Hansen, Signe Munksgaard, Ana Maria Nan, Lanfranco Pellesi, Henrik Schytz. El Salvador: Manuel Vides. Estonia: Kati Braschinsky, Mark Braschinsky, Ülle Krikmann. France: Anne Ducros, Caroline Roos, Alexandre Cauchie, Lucas Christian, Evelyne Guégan-Massardier, Genevieve Demarquay, Geraud Gilles, Jerome Mawet, Emmanuelle Kuhn, Michel Lanteri Minet, Mihaela Bustuchina Vlaicu, Xavier Moisset, Mirela Muresan, Mitra Najjar-Ravan, Pierric Giraud, Sabine Simonin, Solène De Gaalon. Georgia: George Chakhava, Miranda Demuria, George Gegelashvili, Nana Kapanadze. Germany: Angela Antonakakis, Charly Gaul, Stefanie Förderreuther, Jana-Isabel Huhn, Sardor Ibragimov, Katharina Kamm, Bianca Raffaelli, Reiner Czaniera, Ruth Ruscheweyh, Uwe Reuter. Greece: Evangelia Gavanozi, Georgios Karagiorgis, Theodoros Mavridis. Hungary: Csaba Ertsey. India: Dubey Shubham. Indonesia: Antonia Dewi Callista Tanowi, Stefanus Erdana Putra, Deby Wahyuning Hadi, Leny Kurnia, Musadir Nasrul. Italy: Maria Albanese, Fabio Antonaci, Gian Maria Asioli, Roberta Baschi, Enrico Bentivegna, Nicoletta Brunelli, Salvatore Caratozzolo, Teresa Catarci, Alessandra Cherchi, Ilenia Corbelli, Alfredo Costa, Ciro De Luca, Alberto Doretti, Valentina Favoni, Natascia Ghiotto, Maria Adele Giamberardino, Luca Giani, Giorgio Zanchin, Flora Govone, Giovanni Grillo, Edoardo Mampreso, Paolo Martelletti, Andrea Negro, Raffaele Ornello, Marcello Pasculli, Umberto Pensato, Maria Pia Addolorata Prudenzano, Simone Quintana, Rosaria Rapisarda, Michele Romoli, Antonio Russo, Marco Russo, Simona Sacco, Valerio Spuntarelli, Cindy Tiseo, Angelo Torrente, Alessandro Vacca, Giovanna Vaula, Alessandro Viganò, Simone Vigneri. Latvia: Aija Freimane, Evita Slosberga, Linda Zvaune. Malaysia: Hui Jan Tan. Malta: Cherilyn Fenech. Mexico: Rafael Cobilt-Catana, Yazmín De La Garza Neme, Marco Martínez, Jefferson Voltaire Proaño Narvaez, Andrea Rodriguez Herrera, Damaris Vazquez. Moldova: Oxana Grosu. North Macedonia: Adi Jakupi. Norway: Espen Saxhaug Kristoffersen, Erling Tronvik, Bendik S. Winsvold. Pakistan: Mehboob Azhar. Perù: Maria Teresa Reyes Alvarez, Leidi Vilchez Fernandez. Philippines: Greg David Dayrit. Poland: Ewa Katarzyna Czapinska-Ciepiela, Michal Fila, Anna Gryglas-Dworak. Portugal: Marina Couto, Paula Esperança, Axel Ferreira, Raquel Gil-Gouveia, Ana Goncalves, Margarida Lopes, Miguel Lourenço, Jorge Machado, Manuel Marinho, Miguel Angelo Miranda, Filipe Palavra, Elsa Parreira, Isabel Pavao Martins, Liliana Pereira, José Maria Pereira Monteiro. Republic of Moldova: Pavel Leahu. Romania: Stefan Aloman. Russian Federation: Ekaterina Abramova, Leila Akhmadeeva, Anastasia Belopasova, Inna Bogdanova, Mariya Chernyak, Miss Epifanova, Elena Fedorova, Anton Felbush, Maria Karpova, Daria Korobkova, Daria Korotkova, Nina Latysheva, Tatiana Makeeva, Kristina Mikhalkina, Vera Osipova, Olga Roshchina, Anna Serga, O.V. Serousova, Yulia Sidorova, Iaroslav Skiba, Kirill Skorobogatykh, Nina Vashchenko. Serbia: Slobodan Apostolski, Nevenka Buder, Aleksandar Kopitovic, Jovanovic Mirjana, Ana Podgorac, Dejan Rakic, Svetlana Simić, Martinovic Zarko, Jasna Zidverc Trajkovic. Spain: Isabel Beltran-Blasco, María Dolores Calabria Gallego, Samuel Díaz Insa, David Ezpeleta, María Fernández, David García-Azorín, Nuria González-García, Angel L. Guerrero, Edelmira Guillamon, Jaime Herreros Rodriguez, Almudena Layos-Romero, Vicente Medrano, Ane Mínguez-Olaondo, Santiago Navarro Muñoz, Martí Paré Curell, Patricia Pozo-Rosich, Marta Ruibal, Jose Maria Sanchez Alvarez, Margarita Sanchez Del Rio, Sonia Santos, Rafael Soler, Javier Viguera, Ramon Zabalza. Sudan: Tagwa Abdelrahman, Salih Boushra Abobaker Hamza, Mohammed Nasir Mustafa. Sweden: Lars Edvinsson. Switzerland: Andreas Gantenbein, Isabella Maraffi. The Netherlands: Emile Couturier, Thijs Dirkx, Michel Hoebert, Wpj Van Oosterhout, Mulleners Wim, Rachel Zwartbol. Turkey: Mesut Bakır, Hatice Demirel, Ali Kemal Erdemoglu, Devrimsel H. Ertem, Sinan Gönüllü, Elif Ilgaz Aydinlar, Levent Ertuğrul Inan, Berkay Ölmez, Taner Ozbenli, Aynur Özge, Derya Uluduz, Tugba Uyar Cankay, Pinar Yalinay Dikmen. United Arab Emirates: Amrit Bhushan Saxena. Ukraine: Myroslav Bozhenko, Nataliya Bozhenko, Rostyslav Bubnov, Olena Tsurkalenko. United Kingdom: Ishaq Abu-Arafeh, Luis Idrovo, Sarah Miller, Niranjanan Nirmalananthan, Alexandra Sinclair, Esteban Taleti, Alex Valori, William Whitehouse, Adam Zermansky. West Midlands: Myat Thura.

Funding

Publication fees for this publication were covered by the European Headache Federation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

SS and ZK conceived this study and drafted the first version of the questionnaire and of the paper; VC managed the data base and performed statistical analysis; MB, AD, CL, PM, AMVDB, PPR, UR, MSDR, AJ S contributed to develop the questionnaire revised the paper for important intellectual content; PL and ERDLT revised the paper for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the submitted version.

Authors’ information

European Headache Federation (EHF) Council: ZK (president), CL (1st vice-president), AMVDB (2nd vice-president), SS (treasurer), PM (past-president), MB (member), PPR (member), UR (member), MSDR (member), AS (member), AD (member).

European Migraine & Headache Alliance (EMHA): PL (president), ERDLT (Executive Director, Company Secretary and Immediate Past President).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Mark Braschinsky: Fees as a speaker or for participation to advisory boards from Abbott Laboratories, Allergan Inc., Berlin-Chemie AG (Menarini Group), Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH, Desitin Arzneimittel GmbH, EV3, Gedeon Richter Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline, KBM Pharma Ltd., H. Lundbeck A/S, Novartis Pharma Services Inc., Nycomed SEFA, Orion Pharma, Pfizer Inc., Sanofi-Aventis, Sandoz d.d., Scanmed Group, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd./Sicor Biotech UAB, Zentiva International. Previously consultant for H. AbbePharma GmbH, Merz Pharmaceuticals.

Anne Ducros: Fees as speaker or participation to advisory boards from Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Teva.

Zaza Katsarava: Fees as speaker or participation to advisory boards from Novartis, Lilly, TEVA, Allergan, Merck and Daiichi.

Christian Lampl: Fees as speaker or for participation to advisory boards from Allergan, Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva.

Patrick Little: none.

Paolo Martelletti: Fees as speaker or for participation to advisory boards from Allergan, Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Teva.

Antoinette Massen van den Brink: Research grant and/or speaker/consultant fees from Amgen/Novartis, Eli-Lilly, Teva.

Patricia Pozo-Rosich: Fees as consultant and speaker for Allergan, Almirall, Biohaven, Chiesi, The Corpus, Eli Lilly, Medscape, Neurodiem, Novartis and Teva. Research funding from, AGAUR, ERANet Neuron, FEDER RISC3CAT, la Caixa foundation, Instituto Investigación Carlos III, MICINN, Migraine Research Foundation, Novartis, PERIS; funding for clinical trials from Alder, Allergan/AbbVie, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis and Teva.

Uwe Reuter: Fees as consultant and speaker for Allergan, Biohaven, The Corpus, Eli Lilly, Medscape, Novartis, STREAMedUP and Teva. Research funding from BMBF and Novartis, Institutional funding for clinical trials from Alder, Amgen. Allergan, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Teva.

Elena Ruiz de la Torre: none.

Simona Sacco: Fees as speaker or for participation to advisory boards from Abbott, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Eli-Lilly, Medscape, Novartis, Teva.

Margarita Sanchez Del Rio: Fees as speaker or for participation to advisory boards from Allergan, Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Teva.

Alexandra J Sinclair: Fees as speaker from Novartis and Allergan.

Valeria Caponnetto: Fees as member of Advisory Board from Novartis.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

EHF survey on resistant/refractory migraine.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sacco, S., Lampl, C., Maassen van den Brink, A. et al. Burden and attitude to resistant and refractory migraine: a survey from the European Headache Federation with the endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance. J Headache Pain 22, 39 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01252-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01252-4