Abstract

Background

Migraine is a distinct neurological disease that imposes a significant burden on patients, society, and the healthcare system. This study aimed to characterize the incremental burden of migraine in individuals who suffer from ≥4 monthly headache days (MHDs) by examining health-related quality of life (HRQoL), impairments to work productivity and daily activities, and healthcare resource utilization (HRU) in the EU5 (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom).

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study used data from the 2016 National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS; N = 80,600). Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey, version 2 (SF-36v2) physical and mental component summary scores (PCS and MCS), Short-form-6D (SF-6D), and EuroQoL (EQ-5D), impairments to work productivity and daily activities (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI), and HRU were compared between migraine respondents suffering from ≥4 MHDs (n = 218) and non-migraine controls (n = 218) by propensity score matching using sociodemographic characteristics. Chi-square, T-tests, and Mann-Whitney tests were performed to determine significant differences between the groups after propensity score matching.

Results

HRQoL was lower in migraine individuals suffering from ≥4 MHDs compared with non-migraine controls, with reduced SF-36v2 PCS (46.00 vs 50.51) and MCS (37.69 vs 44.82), SF-6D health state utility score (0.62 vs 0.71), and EQ-5D score (0.68 vs 0.81) (for all, p < 0.001). Respondents with migraine suffering from ≥4 MHDs also reported higher levels of absenteeism from work (14.43% vs 9.46%; p = 0.001), presenteeism (35.52% vs 20.97%), overall work impairment (38.70% vs 23.27%), and activity impairment (44.17% vs 27.75%) than non-migraine controls (for all, p < 0.001). Additionally, HRU was significantly higher for individuals with ≥4 MHDs compared to their matched controls. Consistently, migraine subgroups (4–7 MHDs, 8–14 MHDs and CM) had lower HRQoL, greater overall work and activity impairment, and higher HRU compared to non-migraine controls.

Conclusions

Migraine of ≥4 MHDs was associated with poorer HRQoL, greater work productivity loss, and higher HRU compared with non-migraine controls. The findings of the study suggest that an unmet need exists among individuals suffering from ≥4 MHDs in the EU5 suggesting the need for effective prophylactic treatments to lessen the humanistic and economic burden of migraine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Migraine is a distinct neurological disease, associated with recurrent and often debilitating headaches of moderate to severe intensity and accompanied by neurological symptoms (sensory and dysautonomic symptoms including nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or phonophobia) that exact a personal, economic, and societal burden on a global scale [1]. Migraine has been categorized into 2 major types: migraine with aura and migraine without aura. The former accounts for around 30% of the patients and involves transient visual, sensory, and aphasic or motor disturbances that occur before or during migraine attacks [2]. A single migraine attack typically disrupts patient’s life and can consist of premonitory (≤48 h), aura (5–60 min), headache (4–72 h), and resolution/postdrome (≤48 h) phases [3]. Migraine generally starts during puberty and is most prevalent between 30 and 49 years of age [4]. Migraine affects approximately > 10% of the adult population globally [5], is 2–3 times more common in women than men, and tends to run in families and has a genetic trend [6].

Migraine can be immensely disabling [7] and impacts a patient’s functional ability and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) during, immediately after, and between migraine episodes [8].

Migraine was the sixth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide for the age group 25 to 39 years in the 2015 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study [9]. The GBD 2016 study reported migraine as the first leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) worldwide in both males and females for the age group 15 to 49 years, demonstrating that the burden is higher in the groups of prime productivity [10]. In fact, migraine-attributed YLDs were much higher in comparison to other neurological diseases such as epilepsy (ranked 29th) and Alzheimer disease (ranked 26th) [11].

The burden associated with migraine is underestimated even in developed countries despite its high prevalence and severity [12]. Although the prevalence of migraine in individuals suffering from ≥4 monthly headache days (MHDs) is lower when compared to <3MHDs [13], the burden is higher [14]. Studies based on sociodemographic [15] and general health characteristics of migraine [16, 17], HRQoL [18, 19], work productivity loss and activity impairment (WPAI) [17], and healthcare resource utilization (HRU) [17] have been conducted before. Furthermore, a number of studies across multiple countries have studied the impact of chronic and episodic migraine on HRQoL, WPAI, and HRU [7, 18, 20,21,22,23]. However, there is paucity of data on HRQoL, WPAI, and HRU for the entire spectrum of migraine in the EU5 (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) especially in the population with migraine who suffer from ≥4MHDs and may be eligible for prophylactic treatment [13, 24,25,26,27,28,29].

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to characterize the incremental burden of migraine in those experiencing ≥4 MHDs from patients’ perspective in terms of HRQoL, work and activity impairment, and HRU compared with non-migraine controls among the EU5. The secondary objective was to characterize the burden of migraine from the perspective of migraine patients experiencing ≥4 MHDs from the EU5 by frequency of migraine (eg, 4–7, 8–14, and ≥15 MHDs) compared with non-migraine controls.

Methods

Sample

The sample for this retrospective, cross-sectional study was taken from the 2016 National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS; N = 80,600) from adults in the EU5. All respondents were aged 18 years or older, consented to participate in the survey, and could read and write the primary language of the country at the time of the survey.

Respondents to this NHWS are members of MySurvey.com or its partners, which are opt-in survey panels, who were recruited through opt-in e-mail, co-registration with MySurvey.com partners, eNewsletter campaigns, banner placements, and both internal and external affiliate networks. All potential panelists must register with the panel through a unique e-mail address and password and complete an in-depth demographic registration profile. In countries where Internet penetration among the elderly was not considered sufficient to provide an adequate sample of the elderly population (Spain and Italy), telephone recruitment using quota sampling (age and gender) was used to supplement online recruitment, and those without access to the internet were invited to complete the survey using a computer in a private center. The protocol and questionnaire for the NHWS were reviewed for exemption by Pearl Institutional Review Board (IRB) and determined to be exempt from IRB review for the periods the data used in the current study; all respondents provided informed consent.

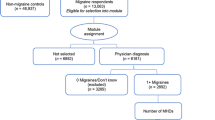

Of the 16,340 survey respondents who reported experiencing migraine in the past 12 months, a randomly selected subsample of 1680 respondents (10%) completed the migraine module with additional questions on migraine characteristics and of these, 771 respondents reported a physician-diagnosed migraine. Such random subsampling enabled inclusion of respondents with different conditions to provide detailed information while limiting the average interview length and respondent’s burden. As the objective was to evaluate the burden of migraine in respondents with ≥4 MHDs, respondents who did not experience migraines in the past month or did not provide a frequency of MHDs or reported rare migraine (≤3 MHDs) were excluded from the study (n = 553) and 218 respondents were included for the study (Fig. 1).

The study sample (respondents who self-reported a physician-diagnosis of migraine) who completed the migraine module and indicated that they experienced migraines of at least 4 MHDs were matched by propensity scores to those without migraines (controls) using sociodemographic characteristics (see below). Furthermore, respondents were categorized according to the frequency of migraines (MHDs): non-migraine controls, people with migraine of 4 to 7 MHDs (4–7 EM), 8 to 14 MHDs (8–14 EM), and 15 or more MHDs (CM) [3].

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics collected included country of residence (i.e., France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom), age in years, gender (male or female), employment status (yes vs no), annual household income (below median vs above median vs decline to answer), marital status (married or living with partner vs not), and level of education (completed university education vs not).

General health characteristics

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from reported height and weight and reported as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 to < 25.0 kg/m2), overweight (25 to < 30.0 kg/m2), obese (30.0 kg/m2 and above), or decline to answer. Other general characteristics collected were cigarette smoking (current vs former vs never); alcohol use (yes vs no); vigorously exercised in past 30 days (yes vs no); and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [30]. CCI weights the presence of various conditions [eg, diabetes, liver disease, connective tissue disease, chronic pulmonary disease, metastatic tumor, moderate/severe renal disease, peripheral vascular disease, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, diabetes with end organ damage, leukemia, dementia, and human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS)] and sums the result. The greater the total index score, the greater is the comorbid burden on the patient.

Health-related quality of life

SF-36v2

The 2016 NHWS included the 4-week recall period of the revised Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Survey Instrument (SF-36v2), which is a multipurpose, generic health status instrument that consists of 36 questions [31]. Two SF-36 summary scores were calculated, physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL. In addition to generating profile and summary PCS and MCS scores, the SF-36v2 can also be used to generate health state utilities, similar to those derived from the EuroQoL EQ-5D (EQ-5D). This is achieved through the application of the Short-Form Six-Dimension (SF-6D), which takes 6 items from the survey.

The SF-6D is a preference-based single index measure for health using UK general population values [32]. The SF-6D index has interval scoring properties and yields summary scores on a theoretical scale of 0 to 1. Higher scores indicate better health status. The EQ-5D Index score is a preference-based measure of health on a theoretical scale of 0 to 1, in which 1 represents full health and 0 being death. It is derived from responses to the 5-level EQ-5D version (EQ-5D-5 L), a widely used survey instrument that measures health in 5 dimensions, which was included in the questionnaire for this study [33].

Work productivity and activity impairment

Loss of productivity and activity impairment were assessed using the General Health version of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI-GH) questionnaire [34], a 6-item validated instrument that consists of 4 metrics: absenteeism (the percentage of work time missed because of one’s health in the past 7 days), presenteeism (the percentage of impairment experienced while at work in the past 7 days because of one’s health), overall work productivity loss (overall work impairment measured by combining absenteeism and presenteeism to determine the total percentage of missed time), and activity impairment (the percentage of impairment in daily activities because of one’s health in the past 7 days). Only respondents who reported being full-time, part-time, or self-employed provided the data for absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment. All respondents completed the activity impairment questionnaire.

Healthcare resource utilization

HRU was defined by visits to different medical providers or healthcare system (i.e., Emergency department [ED] or hospital) 6 months before survey participation due to any medical conditions, not only migraine specific. Several types of healthcare provider (HCP) visits were summarized and analyzed as the presence versus absence of a visit in the prior 6 months as well as the number of visits during that time. The proportion of respondents using healthcare resources was summarized. The HRU of respondents included HCP visits overall, primary care provider visits, neurologist visits, psychiatrist visits, ED/urgent care visits, and hospitalization in the past 6 months.

Matching

As the objective of the study was to estimate the incremental burden associated with migraine, the propensity score of respondents with migraine was compared with that of those without migraine (controls) using demographic and comorbidities data. This procedure was conducted separately within each country and for those with 4–7 EM, 8–14 EM, and CM to limit the risk that respondents differ from controls on matching characteristics within the smaller migraine subgroups.

Logistic regressions including sociodemographic and health variables (age, sex, marital status, income, education, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise behavior, BMI category, and CCI [estimate of comorbidity burden]) were conducted. Using a greedy matching algorithm, respondents’ regression-estimated probabilities were used to match each case to a single control with no reuse of controls. Matching was constrained so that each respondent with migraine was matched to a non-migraine control from the same country.

Data analysis plan

All data management and analyses were performed in SPSS 23.0, and SAS 9.4. The sample was characterized by the variables listed in the variables section using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means, standard deviations for continuous variables.

Differences between respondents diagnosed with migraine versus non-migraine controls were examined. For categorical variables, chi-square tests were used to determine significant differences, whereas t-tests or the Mann-Whitney tests, where appropriate, were used for continuous variables.

Results

Among respondents who reported a physician-diagnosed migraine, suffer from ≥4 MHDs, and completed the migraine module (N = 218), 67 (30.7%) respondents were from the United Kingdom, 59 (27.1%) from Germany, 39 (17.9%) from France, 31 (14.2%) from Italy, and 22 (10.1%) respondents from Spain. The demographic characteristics for respondents diagnosed with migraine and pre-matched and post-matched non-migraine controls are represented in Table 1.

Comparison of respondents with migraine and its subgroups with non-migraine controls

Health-related quality of life

The results from the propensity score matched analysis demonstrated that individuals with migraine who suffer from ≥4 MHDs reported statistically significant lower HRQoL than non-migraine controls, both mentally and physically, as measured by the SF-36v2. The MCS in those with migraine was significantly lower than that in non-migraine controls (37.7 vs 44.8, respectively; p < 0.001; Fig. 2). Furthermore, the PCS score of migraine respondents was significantly lower than that of non-migraine controls (46.0 vs 50.5, respectively; p < 0.001; Fig. 2), this represents an incremental difference of 7.1 in MCS and 4.5 in PCS which is greater than the previously reported MCS and PCS mean for a minimally important difference of 3 [35]. Respondents with migraine also reported significantly lower SF-6D (0.62 vs 0.71, p < 0.001) and EQ-5D (0.68 vs 0.81, p < 0.001) health utility scores than the non-migraine controls (Fig. 3); this represents an incremental difference of 0.09 which is greater than the previously reported mean for a minimally important difference of 0.041 [36]. The significant decrement in PCS and MCS scores was noted across migraine frequency subgroups compared to non-migraine controls suggesting that migraine impacts HRQoL irrespective of frequency (Fig. 2). Furthermore, an increase in the number of MHDs was associated with worse SF-6D utility and EQ-5D health status scores compared to non-migraine controls (Fig. 3).

Work productivity impairment and activity impairment

Respondents with migraine when compared with non-migraine controls reported significantly higher absenteeism (14.4% vs 9.5%, respectively; p = 0.001; Fig. 4) and presenteeism (35.5% vs 21.0%, respectively; p < 0.001; Fig. 4). Higher incremental presenteeism vs non-migraine controls were noted across the migraine sample irrespective of migraine frequency (Fig. 4). Among employed respondents, the total work productivity impairment including both absenteeism, presenteeism, and among all respondents activity impairment was significantly higher in those with migraine than non-migraine controls (38.7% vs 23.3% and 44.2% vs 27.8%, respectively; Fig. 5).

Healthcare resource utilization

HRU was significantly higher in the migraine sample compared with non-migraine controls (Table 2). In the past 6 months before completion of questionnaire, the mean number of total HCP visits (8.5 vs 5.1; p < 0.001) and ED visits (0.46 vs 0.21; p = 0.011) reported by the migraine sample were significantly higher than non-migraine controls. In particular, the mean general/family practitioner visits (3.1 vs 1.7; p < 0.001), neurologist visits (0.19 vs 0.05, p < 0.001), and psychiatrist visits (0.85 vs 0.15; p < 0.001) were significantly higher for the migraine sample when compared with the non-migraine controls. A significantly higher proportion of migraine respondents compared with non-migraine controls had at least one visit to a general/family practitioner (77.1% vs 67.4%; p = 0.025), neurologist (13.8% vs 3.7%; p < 0.001), and psychiatrist (13.3% vs. 3.2%; p < 0.001) in the prior 6 months.

The mean number of hospitalizations in a 6-month period prior to survey was also higher among those with migraine, although marginally significant, compared with non-migraine controls (0.18 vs 0.11; p = 0.056). The proportion of respondents who reported at least one ED visit was significantly higher in the migraine group than non-migraine control (20.6% vs. 12.4%; p = 0.02) whereas the proportion hospitalized (12.8% vs. 7.3% p = 0.056) was higher but marginally significant.

Discussion

The study used responses from patients of a randomly selected subsample who completed the migraine module (10%), and also reported a physician-diagnosed migraine with ≥4 MHDs (Fig. 1); a patient population that is often deemed eligible for prophylactic treatment in clinical trials and practice. The analysis showed that after propensity score matching of the subgroups based on demographic and health characteristics, those suffering from migraine of at least 4 MHDs had significantly lower HRQoL, increased work and activity impairment, and higher HRU than their non-migraine matched controls. The incremental burden due to migraine was demonstrated in all domains of life across migraine frequency subgroups in the migraine spectrum with ≥4 MHDs (4–7 EM, 8–14 EM, and CM), suggesting that every migraine attack is associated with burden impacting the well-being, productivity, and HRQoL of individuals affected. This study used the self-reported data from the 2016 NHWS to provide evidence on multiple dimensions of HRQoL, WPAI, and HRU. The NHWS is a validated recurrent survey conducted across multiple countries and multiple therapy areas using standardized questionnaires to study disease-associated burden [37,38,39,40]. The methodology used ensures representativeness of the general population and is, hence, useful to understand the overall disease burden within a country.

The poorer HRQoL observed in our study in terms of lower physical, mental, and overall health status (utility scores) in those with migraine compared with non-migraine controls is consistent with previous published studies [41, 42]. Similar studies using SF-36 showed migraine to be associated with lower HRQoL in terms of physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perception, vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health in Turkish patients [43] and Malaysian female patients [44]. Furthermore, our results of the SF-6D in those with migraine vs their matched controls showed that migraine is associated with a minimally important decrement in utility.

The Eurolight study which was conducted across multiple countries (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Spain, and UK) showed that migraine is associated with personal impact that affects personal, work, housework and social activities in both men and women who suffer from migraine [8] and therefore significant economic burden to the society [45]. .The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) and other international studies have also shown that migraine impacts all aspects of life and that the burden increases with frequency [7, 46].

The present study showed higher levels of absenteeism (1.5-fold), presenteeism (1.7-fold), work productivity impairment (1.7-fold), and activity impairment (1.6-fold) in those suffering from at least 4 MHDs compared with non-migraine matched controls. This is consistent to previously published studies reporting that migraine can result in substantial loss in useful time and productivity, especially in the form of presenteeism (impaired productivity while at work) [8, 45].

The high burden of migraine is depicted as DALYs and YLDs in the Global Burden Disease study, 2015 especially in those younger than 50 years among whom migraine is in the leading causes of disability [9, 11]. The WHO considers a day lived with severe migraine as disabling as a day lived with dementia, quadriplegia or acute psychosis and more disabling than blindness, paraplegia, angina or rheumatoid arthritis. Migraine impacts not only the persons suffering from migraine but also the healthcare system and society by incremental consumption of healthcare resources and reduced work productivity [25, 45]. Our study showed that HRU in terms of the number of visits to HCP, ED, general/family practitioner, neurologist, and psychiatrist in a 6-month period were significantly higher among the migraine sample than non-migraine controls. These findings are consistent with previous studies in Europe and the US conducted in the overall migraine population where ED visits, hospitalizations, and medicines are among the major cost drivers, while the presence of certain symptoms and/or comorbidities leads to further increase in direct costs [7, 17, 25]; as the frequency and severity of migraine increased, the HRU and economic impact to the healthcare system also increased. It should be noted that the low neurologist visit frequency in our study (13.8%) were similar to previous European studies [13, 27], indicating the lack of specialist healthcare availability in Europe.

Previous European studies have estimated the total cost of migraine at between €18 and €27 billion [45, 47]; these studies refer to the total migraine population and are based on prevalence-based calculations and extrapolation of rough estimates on HRU and costing across multiple countries [45, 47]. Country-specific cost of illness studies are needed to provide a more granular approach into the cost of migraine, especially in those who suffer from at least 4 migraine days per month and are often eligible for prophylaxis. It has been estimated that 77% to 93% of all costs associated with migraine are indirect and attributed to impaired or lost work productivity [47, 48]. Previous studies have often looked at the overall population with migraine, the majority of whom suffer from less than 4 MHDs, and, therefore, the total costs associated with migraine may be underestimated.

The findings of the current study revealed that migraine is associated with high burden for those suffering from ≥4 MHDs affecting not only the sufferers (health status and HRQoL) but indirectly the society, employers, and healthcare system [7, 20, 21, 25]. Furthermore, the study also reported the overall prescription medication use for 4–7 EM, 8–14 EM, and CM subgroups were 49.1%, 46.9%, and 68.3%, respectively. That means that, 50.9% of 4–7 EM, 53.1% of 8–14 EM, and 31.7% of CM subgroups are not being treated even when suffering with ≥4 MHDs. Patients need to be treated with medications which result in reduction of migraine frequency and thus have a substantial impact on improving HRQoL, increasing work productivity, and reducing both activity impairment and associated HRU. Given that the prevalence of migraine peaks in those aged 30 to 49 years—an age of prime productivity on a personal, social and professional level—it is important to address the high unmet need for those affected.

Limitations

There are several limitations that should be noted and which are inherent to these type of studies [49, 50]. .All data are patient-reported via an online panel-based sample and therefore certain biases may exist, therefore caution needs to be taken when interpreting the data.

Despite using the method of administration and randomization to achieve representativeness of the study sample to that of the general population, some bias may still be introduced; this may be due to the inherent differences across different countries as well as access restriction for specific segments of population such as elderly, institutionalized, and those with severe comorbidities and disabilities. Certain efforts were employed to minimize this such as by telephone recruitment where internet access may be limited. The survey responses were self-reported, and data could not be independently verified. The survey questions were relatively benign, and the survey was confidential, diminishing the incentive to misrepresent one’s reporting. All analyses were run in aggregate and no individual-level analysis was conducted.

The self-reported nature of the NHWS is associated with potential corresponding biases such as inaccurate recall and false reporting (whether intentional or unintentional). For example, diagnoses of migraine or other comorbidities (eg, those used in the comorbidity index) were self-reported and are not verified by a physician or medical record. However, questions on year of diagnosis and type of diagnosing physician were also asked which minimizes the probability of false reporting. There is an inherent recall bias to some of the questions that require retrospectively to report outcomes such as HRU. However, major events like an emergency room visit or hospitalization are less likely to be subjected to inaccurate recall compared to a visit to the general practitioner. However, the panel does take adequate measures to minimize intentionally false HRU reporting. For instance, limiting ranges for the number of visits so extreme values aren’t possible, checking for respondents speeding through the survey, or using adaptive questioning to reduce the complexity of the questions.

While measured variables were accounted for in matching and regression, there is the possibility of groups differing on unmeasured variables that may have an impact on outcomes. Although we have tried to match the 2 sample groups by using propensity score matching across different variables (age, gender, BMI, and other factors used), variables that were not considered and could have impacted the analysis may still exist.

Conclusions

The findings of the current study reveal that there is an incremental burden due to migraine on HRQoL (mental, physical, and health status), work productivity (both presenteeism and absenteeism), and the utilization of healthcare resources among those who suffer from migraine ≥4 MHDs in comparison to the matched non-migraine controls in the EU5. Moreover, migraine is undertreated as the patients did not have access to appropriate healthcare, suggesting that effective management and preventive treatments are needed to lessen the frequency and burden of migraine.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- EQ-5D:

-

Euroqol-5D

- EU5:

-

France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- HCP:

-

Healthcare provider

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- HRU:

-

Healthcare resource use

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- MCS:

-

Mental component summary

- MHDs:

-

Monthly headaches days

- NHWS:

-

National Health and Wellness Survey

- PCS:

-

Physical component summary

- SF 36 v2:

-

Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey version 2

- WPAI:

-

Work productivity loss and activity impairment

- WPAI-GH:

-

Work productivity and activity impairment

- YLDs:

-

Years lived with disability

References

(2013) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition Copyright. ßInternational Headache Soc. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202

Donnet A, Daniel C, Milandre L et al (2012) Migraine with aura in patients over 50 years of age: the Marseille’s registry. J Neurol 259:1868–1873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-012-6423-8

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004) The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 24 Suppl 1:9–160.

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M et al (2007) Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 68:343–349. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21

Woldeamanuel YW, Cowan RP (2017) Migraine affects 1 in 10 people worldwide featuring recent rise: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based studies involving 6 million participants. J Neurol Sci 372:307–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.11.071

Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D (2015) Migraine: multiple processes. complex pathophysiology J Neurosci 35:6619–6629. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015

Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK et al (2011) Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the international burden of migraine study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 31:301–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102410381145

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z et al (2014) The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 15(31). https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-31

GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators NJ, Arora M, Barber RM et al (2016) Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388:1603–1658. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T et al (2018) Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50s: will health politicians now take notice? J Headache Pain 19:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0846-2

Vos T, Allen C, Arora M et al (2016) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 388:1545–1602. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6

Cevoli S, D’Amico D, Martelletti P et al (2009) Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of migraine in Italy: a survey of patients attending for the first time 10 headache centres. Cephalalgia 29:1285–1293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01874.x

Radtke A, Neuhauser H (2009) Prevalence and burden of headache and migraine in Germany. Headache 49:79–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01263.x

Ford JH, Jackson J, Milligan G et al (2017) A real-world analysis of migraine: a cross-sectional study of disease burden and treatment patterns. Headache J Head Face Pain 57:1532–1544. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13202

Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM et al (2012) Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American migraine prevalence and prevention study. Headache 52:1456–1470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02223.x

Stokes M, Becker WJ, Lipton RB et al (2011) Cost of health care among patients with chronic and episodic migraine in Canada and the USA: results from the international burden of migraine study (IBMS). Headache 51:1058–1077. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01945.x

Edmeads J, Mackell JA (2002) The economic impact of migraine: an analysis of direct and indirect costs. Headache 42:501–509

Sharma K, Remanan R, Singh S (2013) Quality of life and psychiatric co-morbidity in Indian migraine patients: a headache clinic sample. Neurol India 61:355–359. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.117584

Ayzenberg I, Katsarava Z, Sborowski A et al (2014) Headache-attributed burden and its impact on productivity and quality of life in Russia: structured healthcare for headache is urgently needed. Eur J Neurol 21:758–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12380

Wang S-J, Wang P-J, Fuh J-L et al (2013) Comparisons of disability, quality of life, and resource use between chronic and episodic migraineurs: a clinic-based study in Taiwan. Cephalalgia 33:171–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102412468668

Berra E, Sances G, De Icco R et al (2015) Cost of chronic and episodic migraine. A pilot study from a tertiary headache Centre in northern Italy. J Headache Pain 16:532. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0532-6

Raggi A, Giovannetti AM, Schiavolin S et al (2014) Validating the migraine-specific quality of life questionnaire v2.1 (MSQ) in Italian inpatients with chronic migraine with a history of medication overuse. Qual Life Res 23:1273–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0556-9

Stuginski-Barbosa J, Dach F, Bigal M, Speciali JG (2012) Chronic pain and depression in the quality of life of women with migraine - a controlled study. Headache J Head Face Pain 52:400–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02095.x

Andrée C, Stovner LJ, Steiner TJ et al (2011) The Eurolight project: the impact of primary headache disorders in Europe. Description of methods. J Headache Pain 12:541–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-011-0356-y

Bloudek LM, Stokes M, Buse DC et al (2012) Cost of healthcare for patients with migraine in five European countries: results from the international burden of migraine study (IBMS). J Headache Pain 13:361–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-012-0460-7

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Hernández-Barrera V, Carrasco-Garrido P et al (2010) Population-based study of migraine in Spanish adults: relation to socio-demographic factors, lifestyle and co-morbidity with other conditions. J Headache Pain 11:97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-009-0176-5

Allena M, Steiner TJ, Sances G et al (2015) Impact of headache disorders in Italy and the public-health and policy implications: a population-based study within the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 16:100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0584-7

D’Amico D, Bussone G (2003) Disability and migraine: recent outcomes using an Italian version of MIDAS. J Headache Pain 4:s42–s46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101940300008

Mesas AE, González AD, Mesas CE et al (2014) The association of chronic neck pain, low back pain, and migraine with absenteeism due to health problems in Spanish workers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39:1243–1253. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000387

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Maruish ME (Ed.) (2011) User’s manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey (3rd ed.). Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M (2002) The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 21:271–292

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al (2011) Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 20:1727–1736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM (1993) The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 4:353–365

Swigris JJ, Brown KK, Behr J et al (2010) The SF-36 and SGRQ: validity and first look at minimum important differences in IPF. Respir Med 104:296–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2009.09.006

Walters SJ, Brazier JE (2005) Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res 14:1523–1532

Meneghini LF, Lee L, Gupta S, Preblick R (2018) The association of hypoglycaemia severity and clinical, patient-reported and economic outcomes in US patients with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin. Diabetes Obes Metab. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13208

Arima K, Gupta S, Gadkari A et al (2018) Burden of atopic dermatitis in Japanese adults: analysis of data from the 2013 National Health and wellness survey. J Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14218

Ding B, DiBonaventura M, Karlsson N, Ling X (2017) A cross-sectional assessment of the prevalence and burden of mild asthma in urban China using the 2010, 2012, and 2013 China National Health and wellness surveys. J Asthma 54:632–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2016.1255750

Balp M-M, Vietri J, Tian H, Isherwood G (2015) The impact of chronic Urticaria from the Patient’s perspective: a survey in five European countries. Patient 8:551–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0145-9

Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Kolodner KB et al (2000) Migraine, quality of life, and depression: a population-based case-control study. Neurology 55:629–635

Lipton R, Liberman J, Kolodner K et al (2003) Migraine headache disability and health-related quality-of-life: a population-based case-control study from England. Cephalalgia 23:441–450. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00546.x

Arslantas D, Tozun M, Unsal A, Ozbek Z (2013) Headache and its effects on health-related quality of life among adults. Turk Neurosurg 23:498–504. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.7304-12.0

Shaik MM, Hassan NB, Tan HL, Gan SH (2015) Quality of life and migraine disability among female migraine patients in a tertiary Hospital in Malaysia. Biomed Res Int 2015:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/523717

Stovner LJ, Andrée C, Committee ES (2008) Impact of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 9:139–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-008-0038-6

Munakata J, Hazard E, Serrano D et al (2009) Economic burden of transformed migraine: results from the American migraine prevalence and prevention (AMPP) study. Headache 49:498–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01369.x

Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M et al (2012) The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol 19:155–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03590.x

Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ et al (2012) The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol 19:703–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03612.x

Goren A, Liu X, Gupta S et al (2013) Quality of life, activity impairment, and healthcare resource utilization associated with atrial fibrillation in the US National Health and wellness survey. Am. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071264

Kalsekar I, Wagner J-S, Dibonaventura M, et al (2012) Comparison of health-related quality of life among patients using atypical antipsychotics for treatment of depression: results from the National Health and Wellness Survey. ??? 10:1 . doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-81

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Uma Dasam and Ramu Periyasamy, Ph.D., Indegene Pvt. Ltd.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Novartis Pharma AG, Switzerland.

Availability of data and materials

NHWS data used in this study are available for noncommercial research and validation purposes, upon request. Interested individuals may access these data for the purposes above in the same manner as the authors did without any additional restrictions. Interested parties should contact the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PV, JF, AB, AKL, and SG conceived and designed the study. SG analyzed the data. PV, JF, AB, AKL and SG interpreted the results and helped write the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The NHWS received approval from the Pearl Institutional Review Board. All NHWS respondents provided informed consent prior to participating.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publish the results presented here.

Competing interests

SG is an employee of Kantar Health, which conducted the NHWS and received funding to analyze and develop the manuscript from Novartis. PV, JF and AKL are employees of Novartis, which funded the current study. AB was a Novartis employee at the time of the study completion and manuscript preparation.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vo, P., Fang, J., Bilitou, A. et al. Patients’ perspective on the burden of migraine in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis of survey data in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Headache Pain 19, 82 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0907-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0907-6