Abstract

Background

We have genotyped a Swedish cluster headache case-control population for three genetic variants representing the most significant markers identified in a recently published genome wide association study on cluster headache. The genetic variants were two common polymorphisms; rs12668955 in ADCYAP1R1 (adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 receptor type 1), rs1006417, an intergenic variant on chromosome 14q21 and one rare mutation, rs147564881, in MME (membrane metalloendopeptidase).

Results

We screened 542 cluster headache patients and 581 controls using TaqMan real-time PCR on a 7500 fast cycler, and pyrosequencing on a PSQ 96 System. Statistical analysis for genotype and allele association showed that neither of the two common variants, rs12668955 and rs1006417 were associated with cluster headache. The MME mutation was investigated with pyrosequencing in patients, of whom all were wild type.

Conclusion

In conclusion rs12668955 and rs1006417 do not impact the risk of developing cluster headache in the Swedish population. Also, rs147564881 does not seem to be enriched within the Swedish cluster headache patient group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cluster headache (CH) is a severe primary headache affecting around 0.1-0.2% of the Swedish population [9]. There are no known causes of CH today, but a genetic component in the etiology is suggested. For instance, having a first or second degree relative with CH implies an increased risk of developing CH [4]. Twin studies also provide an indication of genetic influence in CH. Apart from case-reports identifying occasional monozygotic twins with CH, Ekbom et al. reported two concordant monozygotic twin pairs in a population of over 30,000 individuals in an interview-based register study from 2006, indicating that there is a weak heritability for CH [6, 9, 11, 16, 18]. In addition, there have been several reports of genetic associations linking genetic variations in several candidate genes to CH. Hypocretin receptor 2 (HCRTR2) and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) are examples of such genes, representing a link between the molecular pathways involved in the pathophysiology, and genetic risk-factors [3, 14, 19]. HCRTR2 in particular has received a lot of attention due to its involvement in the regulation of sleep and pain, functions highly relevant in the CH pathophysiology [5]. Moreover, hypocretin-1 levels are reported to be reduced in the ceresbrospinal fluid in CH patients [2]. Recently the first genome wide association study (GWAS) on a CH cohort was published. Though underpowered, the GWAS data indicated a few genetic markers potentially of interest for CH pathophysiology which warrant more thorough investigation [1].

We selected the top three associations from Bacchelli et al.; rs1006417, an intergenic variant on chromosome 14q21; rs12668955 in adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 receptor type 1 (ADCYAP1R1) and one rare mutation, rs147564881, in the membrane metallo-endopeptidase gene (MME), and performed a replication study on a well characterized and large Swedish CH case-control population. Replicating GWAS findings in independent materials is a crucial step in the validation of GWASs. In particular when the discovery cohort is small, it is important to verify the association and evaluate the importance of the identified markers in patients from different genetic backgrounds. ADCYAP1R1 and MME are attractive candidate genes since they are both involved in pain signaling, and our study may shed more light on the possibility of these genetic markers being involved in the pathophysiology of CH.

Methods

We genotyped 542 CH patients and 581 controls for two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); rs12668955 and rs1006417, and one rare mutation; rs147564881. All experiments were approved by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm, Sweden. CH patients were recruited after informed consent at the Neurology Department at Karolinska University Hospital, or through collaboration with neurologists at other clinics in the central part of Sweden. Diagnosis was confirmed by a neurologist and complied with the guidelines of the 3rd version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD III) [20]. Patients were requested to provide personal, clinical and lifestyle information through a questionnaire and give a blood sample. Of the CH patients 31.7% were female, average age 52 years, median age 53 years, 10.3% had chronic CH, age of onset was 31.6 years and 10.8% reported they had at least one first or second degree relative with CH (53 patients of 489 for whom the information was available). Control subjects were anonymous healthy blood donors, of whom 44% were females, between the age 18 and 65.

DNA was prepared from blood using the Gentra Puregene Blood kit according to standard protocols (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Genotyping was performed with TaqMan quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) on an ABI 7500 Fast cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). We used pre-made TaqMan SNP genotyping assays, C__32158964_10 for rs12668955 and C__2056560_10 for rs1006417, and TaqMan genotyping master mix (Applied Biosystems).

TaqMan genotyping was unsuccessful for the rare mutation rs147564881, therefore we used pyrosequencing to analyze the MME mutation. We used primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) designed in-house using primer3 and mfold software, as well as the NCBI online Blast tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), sequence available on request [10, 21, 22]. The genomic region of interest was amplified with a touchdown PCR spanning from 45 to 55 °C using one regular primer and one biotinylated primer. The PCR fragments were denatured and the biotin containing fragments were annealed to streptavidin-sepharose beads using a PyroMark Vacuum Prep tool (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden), washed and incubated with the pyrosequencing primer at 80 °C for 2 min, and then analysed in an automated pyrosequencing PSQ 96 System using PyroMark Gold reagents (QIAGEN).

Chi-squared (χ2) test was used for statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism v5.04 (GraphPad Softwares Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Fisher’s exact test was used for the additional dominant genotypic model. Both SNPs were tested for Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using the Online Encyclopedia for Genetic Epidemiology studies HWE calculator [15].

Results

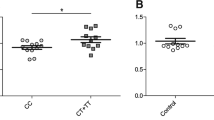

We genotyped 542 CH patients and 581 control subjects for two SNPs, rs12668955 and rs1006417 that were recently suggested to confer decreased risk for CH in a GWAS. Both SNPs were in HWE in both cases and controls (data not shown). rs12668955 genotype and allele frequencies were similarly distributed between cases and controls. The wild-type genotype and allele of rs1006417 appeared to be more common in the control group as compared to CH patients, however this was not reflected by the statistical analysis (Table 1). Genotype and allele analysis with χ2 revealed that none of the SNPs were associated with CH (Table 1). Since the genotype frequencies differed slightly between cases and controls for rs1006417, we further analyzed this SNP under a dominant genotypic model (AA vs. AG + GG) using a Fisher’s exact test. This analysis was consistent with the basic χ2 test and showed no significant association between rs1006417 and CH (odds ratio 1.21, 95% confidence interval of 0.95-1.54 and a p-value of 0.12). We also investigated the presence of the rare mutation rs147564881 in the MME gene in our CH population. The genomic region was difficult to analyze because of low guanine-cytosine content. Using pyrosequencing we acquired a readable sequence for 492 individuals (91% of the patients), all of whom were wild-type. Because of the lack of mutation carriers in the CH patients we did not proceed with genotyping of the controls.

Discussion

We have performed a replication study based on the recent findings of the first published GWAS on CH. The three most significant variants, rs12668955, rs1006417 and rs147564881 were selected and genotyped in a Swedish CH case-control study population. We found no association for either genotypes or alleles with CH for the common SNPs, and further we found no CH patient carrying the mutated allele of rs147564881. The discrepancy between our study and the discovery study can have several reasons. The control materials exhibit considerable differences. The Italian GWAS used 360 cigarette smokers, while we used anonymous blood donors, 14% of which are presumably smokers, as this is the proportion of smokers in the Swedish population. Moreover, there is a significant difference in gender ratio between the Swedish and the Italian material. The Italian cohort have an unusually high proportion of males (84%) compared to the Swedish cohort (68,3%). As a control experiment, we therefore verified our results in a gender stratified analysis conducted with male subjects only, successfully replicating a lack of association. Also, there might be differences in genetic background between the Swedish and Italian populations. The minor allele frequencies (MAF) for the two common SNPs differs between our study and the Italian report, in particular for rs1006417 which is protective in the Italian study. In our material, although the difference is non-significant, cases have a higher MAF (0.245) than controls (MAF 0.216) which would be indicative of an increased rather than decreased risk. The association discovered in the Italian cohort might also reflect a linkage disequilibrium (LD) between these SNPs and other genetic variations truly linked to disease that are not present in the Swedish population. Since we did not genotype any additional marker at these loci, we could not control for a potential difference in the LD structure between the Swedish and Italian populations. Another limitation of our study is the possibility that other rare MME mutations might be associated to CH in our material. Last, life style and environmental factors, e.g. seasonal variation has been reported to influence CH, smoking is a risk factor for CH, other plausible factors might be inflammations and diet, [7, 8, 12, 13, 17], and gene-environment interactions might cause genetic risk factors to differ in specific populations or various parts of the world.

Conclusion

In conclusion rs12668955 and rs1006417 do not impact the risk of developing CH in the Swedish population. Also, rs147564881 is a rare mutation which does not seem to be enriched within the Swedish CH patient group.

Abbreviations

- ADCYAP1R1:

-

Adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1 receptor type 1

- CH:

-

Cluster headache

- df:

-

Degrees of freedom

- GWAS:

-

Genome wide association study

- HCRTR2:

-

Hypocretin receptor 2

- HWE:

-

Hardy Weinberg equilibrium

- ICHD:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- IHS:

-

The Iternational Headache Society

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequencies

- MME:

-

Membrane metalloendopeptidase

- NOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- χ2 :

-

Chi-square

References

Bacchelli E, Cainazzo MM, Cameli C et al (2016) A genome-wide analysis in cluster headache points to neprilysin and PACAP receptor gene variants. J Headache Pain 17:114. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0705-y

Barloese M, Jennum P, Lund N et al (2015) Reduced CSF hypocretin-1 levels are associated with cluster headache. Cephalalgia 35:869–876. doi:10.1177/0333102414562971

Baumber L, Sjöstrand C, Leone M et al (2006) A genome-wide scan and HCRTR2 candidate gene analysis in a European cluster headache cohort. Neurology 66:1888–1893. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219765.95038.d7

Bjørn Russell M (2004) Epidemiology and genetics of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol 3:279–283. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00735-5

Chiou L-C, Lee H-J, Ho Y-C et al (2010) Orexins/hypocretins: pain regulation and cellular actions. Curr Pharm Des 16:3089–3100

Couturier EG, Hering R, Steiner TJ (1991) The first report of cluster headache in identical twins. Neurology 41:761

Di Lorenzo C, Coppola G, Sirianni G et al (2015) O045. Cluster headache improvement during Ketogenic diet. J Headache Pain 16:A99. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-16-S1-A99

Eising E, Pelzer N, Vijfhuizen LS et al (2017) Identifying a gene expression signature of cluster headache in blood. Sci Rep 7:40218. doi:10.1038/srep40218

Ekbom K, Svensson DA, Pedersen NL, Waldenlind E (2006) Lifetime prevalence and concordance risk of cluster headache in the Swedish twin population. Neurology 67:798–803. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000233786.72356.3e

Koressaar T, Remm M (2007) Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics 23:1289–1291. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091

Kowacs PA, Piovesan EJ, Werneck LC et al (2004) Report of cluster headache in a pair of monozygous twins. J Headache Pain 5:140–143 doi: 0.1007/s10194-004-0082-9

Levi R, Edman GV, Ekbom K, Waldenlind E (1992) Episodic cluster headache. II: high tobacco and alcohol consumption in males. Headache 32:184–187

Ofte HK, Berg DH, Bekkelund SI, Alstadhaug KB (2013) Insomnia and periodicity of headache in an Arctic cluster headache population. Headache J Head Face Pain 53:1602–1612. doi:10.1111/head.12241

Rainero I, Gallone S, Valfrè W et al (2004) A polymorphism of the hypocretin receptor 2 gene is associated with cluster headache. Neurology 63:1286–1288. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000142424.65251.DB

Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Day INM (2008) Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for Mendelian randomization studies. Am J Epidemiol 169:505–514. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn359

Schuh-Hofer S, Meisel A, Reuter U, Arnold G (2003) Monozygotic twin sisters suffering from cluster headache and migraine without aura. Neurology 60:1864–1865. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000066050.07400.60

Schurks M, Kurth T, de Jesus J et al (2006) Cluster headache: clinical presentation, lifestyle features, and medical treatment. Headache J Head Face Pain 46:1246–1254. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00534.x

Sjaastad O, Shen JM, Stovner LJ, Elsås T (1993) Cluster headache in identical twins. Headache 33:214–217

Sjöstrand C, Modin H, Masterman T et al (2002) Analysis of nitric oxide synthase genes in cluster headache. Cephalalgia 22:758–764

The Iternational Headache Society (IHS) (2013) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33:629–808. doi:10.1177/0333102413485658

Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, et al 2012Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. doi:10.1093/nar/gks596

Zuker M (2003) Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31:3406–3415. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg595

Acknowledgements

We thank Ann-Christin Karlsson for her efforts in recruiting patients to the biobank.

Funding

This work was supported by Lennanders stiftelse, the Swedish Brain Foundation, Swedish Research Foundation, Åke Wibergs Stiftelse, Svenska Migränsällskapet, and Karolinska Institutet Research funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CR participated in the design of the study, performed the genotyping, the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. CF and JMM have prepared DNA, participated in the genotyping and analysis and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AS, CS, EW have recruited the study participants, verified the clinical diagnosis of all patients, contributed to the scientific content and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. ACB conceived the study, participated in its planning and coordination, data analysis and was involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ran, C., Fourier, C., Michalska, J.M. et al. Screening of genetic variants in ADCYAP1R1, MME and 14q21 in a Swedish cluster headache cohort. J Headache Pain 18, 88 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0798-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0798-y