Abstract

Background

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS, defined as Epworth sleepiness scale score > 10) is a common symptom, with a prevalence of 10–20% in the general population. It is associated with headache and other chronic pain disorders. However, little is known about the prevalence of EDS among people with secondary chronic headaches.

Findings

A total of 30,000 persons aged 30–44 from the general population was screened for headache by a questionnaire. The 633 eligible participants with self-reported chronic headache were interviewed and examined by a headache specialist who applied the International Classification of Headache Disorders with supplementary definitions for chronic rhinosinusitis and cervicogenic headache. A total of 93 participants had secondary chronic headache and completed the ESS.

A total of 47 participants had chronic post-traumatic headache (CPTH) and/or cervicogenic headache (CEH), 39 participants had headache attributed to chronic rhinosinusitis (HACRS), while 7 had other secondary headaches. 23.3% of those with CPTH, CEH or HACRS reported EDS. In multivariable logistic regression analysis the odds ratios of EDS were not significantly different in people with CPTH/CEH or HACRS.

Conclusion

Almost one out of four subjects with secondary chronic headache reported EDS with no differences between the various secondary chronic headaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Headache and sleep complaints are prevalent in the general population and often coexist in the same subject [1]. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is associated with neurological disorders and pain [2, 3]. Only a few studies have investigated EDS in headache [4,5,6,7,8,9,10], and the results are not uniform, possibly due to differences in methods and patient populations [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. We have previously reported on the prevalence of EDS in primary chronic headaches in the general population [11].

To our knowledge EDS has not been evaluated in people with secondary chronic headache. Thus, in the present study we investigated the prevalence of, and factors associated with EDS in participants from the general population with different secondary chronic headaches.

Findings

Methods

Study design, population and variables

This was a cross-sectional epidemiological survey of 30,000 representative persons aged 30–44 drawn from the general population of eastern Akershus County, Norway. A postal questionnaire screened for possible chronic headache (≥15 days/last month and/or ≥180 days/last year). Screening-positive subjects were invited to a clinical interview at Akershus University Hospital.

In total 71% (20,598/28,871) of the study population responded to the screening questionnaire. Of 935 patients with self-reported chronic headache, 633 participated in clinical interviews (490 as an ambulatory visit, 143 by telephone). The method has been described in detail elsewhere [12, 13].

After the interview, the participants filled in a self-administered questionnaire including the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [14]. The participants also provided information on socio-demographics, height, weight, smoking status, medication-overuse, headache frequency and headache disability by Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) [15].

Headache classification

The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II) was applied in the interview. The diagnoses were later reclassified according to ICHD IIIβ [16]. Those with secondary chronic headache exclusively due to medication overuse were excluded.

Chronic headache was defined as headache ≥15 days/months for at least 3 months or ≥180 days/year. Chronic post-traumatic headache (CPTH) included head and whiplash traumas. Cervicogenic headache (CEH) was classified according to the criteria of the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group, requiring at least three criteria to be fulfilled, not including blockade of the neck due to the non-interventional nature of our study (Table 1) [17]. Headache attributed to chronic rhinosinusitis (HACRS) was defined according to the criteria established by the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (Table 2) adding that the symptoms had persisted for 12 weeks or more [18].

Excessive daytime sleepiness

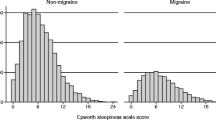

The ESS questionnaire describes eight daily situations in which the respondents estimate their likelihood of dozing off on a 0─3 scale, i.e. 0 = no chance, 1 = slight chance, 2 = moderate chance, 3 = high chance [14]. The ESS total scores (0─24) were dichotomized into scores ≤10 and >10; the latter is considered to be clinically significant EDS [19].

Statistical analysis

For descriptive data, proportions, means and SDs or 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given. We estimated binomial confidence intervals for proportions. Groups were compared using the t-test (continuous data) or the χ 2 test (categorical data).

Logistic regression models were used to evaluate presence of EDS as the dependent variable in secondary chronic headaches. Because of the low prevalence of EDS in the sample, we restricted the number of independent variables in multivariable analysis to three. All logistic regression models were estimated using penalized likelihood to reduce small-sample bias in maximum likelihood estimation [20, 21]. We conducted (1) bivariate analysis with type of chronic headache, i.e. CPTH/CER or HACRS, medication overuse (yes or no), and a propensity score (the propensity for having HACRS compared to CPTH/CER in a multivariable logistic regression model with age, sex, headache frequency, and concomitant migraine as independent variables), and (2) multivariable analysis forcing all three independent variables into the model. The results are presented with odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs.

Significance levels were set at p < 0.05, using two-sided test. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Ethical issues

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Social Science Data Services approved the study. All participants gave informed consent.

Results

In total 93 of the 113 eligible participants (82%) completed the ESS. Respondents and non-respondents to the ESS did not differ in age, gender composition or the distribution of headache diagnoses (data not shown).

A total of 36 people had CPTH, 19 people had CEH and 40 people had HACRS. Co-occurrence of CPTH and CEH was found in 7 people, while one person had co-occurrence of CPTH and HACRS. Six persons had other secondary chronic headaches, i.e. 3 post-craniotomy, 1 diving related, 1 pregnancy-related, and 1 post-meningitis.

Seven of those with CPTH, seven of those with CEH and ten of those with HACRS reported EDS, respectively. Only one of those with other secondary chronic headache reported EDS.

The people with CPTH and CEH were descriptive similar (gender, co-occurrence of migraine, medication overuse, ESS or EDS) and were merged for the purpose of statistical analyses. We included people with CPTH/CER and HACRS in the main analyses and excluded those seven persons with other secondary chronic headaches due to the low numbers and consequent statistical limitations.

The respondents with CPTH/CER had a higher proportion of subjects with headache frequency above the 75th percentile (≥90 headache days the past 3 months) and more severe disability than those with HACRS (Table 3).

The overall prevalence of EDS was 23% (95% CI 16─33) among those with CPTH, CER or HACRS; 22% (95% CI 14─33) among women and 28% (95% CI 13─51) among men (Table 4). The prevalence of EDS in CPTH/CER without versus with co-occurrence of migraine was 24% (95% CI 12─42) and 17% (95% CI 6─39), respectively (p = 0.54). The prevalence of EDS in HACRs without versus with co-occurring migraine was 16% (95% CI 6─38) and 35% (95% CI 18─57), respectively (p = 0.17).

Headache diagnosis, medication overuse or the composite propensity score (age, gender, headache frequency and co-occurring migraine) was not associated with EDS in bivariate or multivariable analysis (Table 5).

Applying the χ 2-test in non-adjusted analyses, no significant differences (data not shown) were found in those with and without EDS depending on socio-demographics, body mass index, smoking, alcohol, caffeine, other sleep disorders, anxiety/depression, comorbidity of other disorders or medication use for other conditions.

Discussion

In this large population-based study almost one out of four subjects with secondary chronic headache reported EDS. The main finding was that the prevalence of EDS did not differ between those with CPTH/CEH and HACRS. Furthermore, medication-overuse, or the composite propensity score (age, gender, headache frequency and co-occurring migraine) was not associated with EDS in this population.

No previous study has investigated EDS for secondary chronic headache in the general population. The prevalence of EDS in men and women with secondary chronic headache corresponds to that for people with primary chronic headache in the general population (20.6% among women, 22.5% among men) and is comparable to data reported from the Norwegian general population (16.1% among women, 20.1% among men) [11, 22]. Here, we did not include a directly comparable headache-free control group and caution is therefore warranted in this comparison. Also, due to the limited sample size in the present study, the risk of type 2 errors must be considered.

Little is known about the precise relationship between headache and sleep problems, when these occur concurrently. An association between EDS and different pain conditions has been reported [2, 3]. Pain may disturb sleep and give rise to EDS, but sleep loss and EDS may also contribute to pain. Some of these secondary headaches are poorly understood, thus, further research is warranted [23]. Studies suggest that CEH can be explained by local factors in the neck with dysfunction of the neck muscles and mechanical cervical spine pathology leading to limited cervical movements and projection of the pain [24]. Headaches attributed to head trauma and whiplash trauma have instead been suggested to represent an interplay between the physical injury, neuroinflammation, psychological disturbances and emotional stress of the accident [25, 26]. Finally, longstanding oedema of the nasal mucosa and rhinosinal inflammation result in chronic rhinosinusitis which may give chronic headache [12]. The present study reported that CPTH/CEH and HACRS had similar prevalence of EDS despite these different headache forms probably being caused by different pathophysiological mechanisms. Therefore, it may be the complex burden of pain, more than the specific condition that is associated with EDS. Furthermore, the prevalence was comparable to that of two other different headache entities; chronic migraine and chronic tension-type headache [11].

The population-based sample in the present study was large, and the high response rate should ensure that the sample was representative of the general population. Even though the sample size of secondary chronic headache may seem small, this is the largest sample of subjects with secondary chronic headache recruited from the general population.

The diagnostic criteria of CEH and HACRS have been discussed for many years [12, 27]. When the study was conducted the more vague ICHD-II criteria for CEH were in use and HACRS was not recognized as a cause of chronic headache. Thus, to improve the diagnostic accuracy we used supplementary definitions. All patients diagnosed with CEH or HACRS in the present study fulfil the new ICHD-IIIβ criteria for these chronic headaches.

Face-to-face interviews by headache experts, as in the present study, provide more valid headache diagnoses than questionnaire-based studies [28]. The ESS is a widely used, validated questionnaire for evaluating subjective daytime sleepiness, and the score is associated with clinically important outcomes, such as cognitive impairment, cardiovascular mortality, and injuries [29, 30].

The 30–44 years age range in our study was chosen in order to ascertain a general population sample without much co-morbidity of non-headache disorders. Because EDS varies with age, our findings may not be generalizable to younger or older populations. The study lacked data on sleep quality and sleep duration that may be associated with sleepiness in headache [5, 6, 8, 9].

The overall sample size limited the number of variables that could be analyzed as potential confounders, and this also lead us to dichotomize many variables for use in the analyses. Also, due to the small number in the present study, the risk of type 2 errors must be considered. Finally, the cross-sectional design in the present study does not permit any conclusions about causality.

In conclusion, there was no difference in the prevalence of EDS between subgroups of different secondary chronic headache diagnoses.

References

Rains JC, Poceta JS, Penzien DB (2008) Sleep and headaches. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 8:167–175

Wolfe F, Michaud K, Li T (2006) Sleep disturbance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: evaluation by medical outcomes study and visual analog sleep scales. J Rheumatol 33:1942–1951

Dyken ME, Afifi AK, Lin-Dyken DC (2012) Sleep-related problems in neurologic diseases. Chest 141:528–544

Peres MF, Stiles MA, Siow HC, Silberstein SD (2005) Excessive daytime sleepiness in migraine patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:1467–1468

Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Fofi L, Vanacore N (2013) A case-control study on excessive daytime sleepiness in chronic migraine. Sleep Med 14:278–281

Seidel S, Hartl T, Weber M, Matterey S, Paul A, Riederer F et al (2009) Quality of sleep, fatigue and daytime sleepiness in migraine - a controlled study. Cephalalgia 29:662–669

Odegard SS, Engstrom M, Sand T, Stovner LJ, Zwart JA, Hagen K (2010) Associations between sleep disturbance and primary headaches: the third Nord-Trondelag Health Study. J Headache Pain 11:197–206

Stavem K, Kristiansen HA, Kristoffersen ES, Kvaerner KJ, Russell MB (2017) Association of excessive daytime sleepiness with migraine and headache frequency in the general population. J Headache Pain 18:35

Kim J, Cho SJ, Kim WJ, Yang KI, Yun CH, Chu MK (2016) Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with an exacerbation of migraine: A population-based study. J Headache Pain 17:62

Karthik N, Kulkarni GB, Taly AB, Rao S, Sinha S (2012) Sleep disturbances in 'migraine without aura'--a questionnaire based study. J Neurol Sci 321:73–76

Kristoffersen ES, Stavem K, Lundqvist C, Russell MB (2017) Excessive daytime sleepiness in chronic migraine and chronic tension-type headache from the general population. Cephalalgia E-pub ahead of print

Aaseth K, Grande RB, Benth JS, Lundqvist C, Russell MB (2011) 3-Year follow-up of secondary chronic headaches: the Akershus study of chronic headache. Eur J Pain 15:186–192

Kristoffersen ES, Lundqvist C, Aaseth K, Grande RB, Russell MB (2013) Management of secondary chronic headache in the general population: the Akershus study of chronic headache. J Headache Pain 14:5

Johns MW (1991) A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14:540–545

Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Whyte J, Dowson A, Kolodner K, Liberman JN et al (1999) An international study to assess reliability of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score. Neurology 53:988–994

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2013) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33:629–808

Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA, Pfaffenrath V (1998) Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. The Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group. Headache 38:442–445

Benninger MS, Ferguson BJ, Hadley JA, Hamilos DL, Jacobs M, Kennedy DW et al (2003) Adult chronic rhinosinusitis: definitions, diagnosis, epidemiology, and pathophysiology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129:S1–32

Johns MW (1994) Sleepiness in different situations measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 17:703–710

Allison P (2012) Logistic Regression for Rare Events https://statisticalhorizons.com/logistic-regression-for-rare-events (accessed June 2017)

Coveney J (2015) FIRTHLOGIT: Stata module to calculate bias reduction in logistic regression (Program)

Pallesen S, Nordhus IH, Omvik S, Sivertsen B, Tell GS, Bjorvatn B (2007) Prevalence and risk factors of subjective sleepiness in the general adult population. Sleep 30:619–624

Olesen J, Steiner T, Bousser MG, Diener HC, Dodick D, First MB et al (2009) Proposals for a new standardized general diagnostic criteria for the secondary headaches. Cephalalgia 29:1331–1336

Bogduk N, Govind J (2009) Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 8:959–968

Schrader H, Obelieniene D, Bovim G, Surkiene D, Mickeviciene D, Miseviciene I et al (1996) Natural evolution of late whiplash syndrome outside the medicolegal context. Lancet 347:1207–1211

Obermann M, Naegel S, Bosche B, Holle D (2015) An update on the management of posttraumatic headache. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 8:311–315

Fredriksen TA, Antonaci F, Sjaastad O (2015) Cervicogenic headache: too important to be left un-diagnosed. J Headache Pain 16:6

Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Olesen J (1991) Questionnaire versus clinical interview in the diagnosis of headache. Headache 31:290–295

Jackson ML, Howard ME, Barnes M (2011) Cognition and daytime functioning in sleep-related breathing disorders. Prog Brain Res 190:53–68

Empana JP, Dauvilliers Y, Dartigues JF, Ritchie K, Gariepy J, Jouven X et al (2009) Excessive daytime sleepiness is an independent risk indicator for cardiovascular mortality in community-dwelling elderly: the three city study. Stroke 40:1219–1224

Acknowledgments

Kjersti Aaseth and Ragnhild Berling Grande conducted the clinical interviews.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the South East Norway Regional Health Authority and Institute of Clinical Medicine, Campus Akershus University Hospital, University of Oslo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MBR had the original idea for the study and planned the overall design together with CL. All authors were involved in the planning and interpretation of the data analysis. ESK and KS conducted the data analysis. ESK prepared the initial draft. All authors have commented on, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kristoffersen, E.S., Stavem, K., Lundqvist, C. et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in secondary chronic headache from the general population. J Headache Pain 18, 85 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0794-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0794-2