Abstract

Background

Insomnia is a common complaint among individuals with migraine. The close association between insomnia and migraine has been reported in clinic-based and population-based studies. Probable migraine (PM) is a migrainous headache which fulfills all but one criterion in the migraine diagnostic criteria. However, an association between insomnia and PM has rarely been reported. This study is to investigate the association between insomnia and PM in comparison with migraine using data from the Korean Headache-Sleep Study.

Methods

The Korean Headache-Sleep Study is a nation-wide cross-sectional survey for all Korean adults aged 19–69 years. The survey was performed via face-to-face interview using a questionnaire on sleep and headache. If an individual’s Insomnia Severity Index score was ≥15.5, she/he was diagnosed as having insomnia.

Results

Of 2695 participants, the prevalence of migraine, PM and insomnia was 5.3, 14.1 and 3.6 %, respectively. The prevalence of insomnia among subjects with PM was not significantly different compared to those with migraine (8.2 % vs. 9.1 %, p = 0.860). However, insomnia prevalence in subjects with PM was significantly higher than in non-headache controls (8.2 % vs. 1.8 %, p < 0.001). Insomnia Severity Index score was significantly higher in subjects with migraine compared to those with PM (6.8 ± 5.8 vs. 5.5 ± 5.8, p = 0.012). Headache frequency and Headache Impact Test-6 score were significantly higher in subjects with migraine and PM with insomnia compared to those without insomnia. Multivariable linear analyses showed that anxiety, depression, headache frequency and headache intensity were independent variables for contributing the ISI score among subjects with PM.

Conclusions

The prevalence of insomnia among subjects with PM was not significantly different compared to those with migraine. Anxiety, depression, headache frequency and headache intensity were related with ISI score in subjects with PM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Insomnia and migraine are common complaints among the general population, affecting 10–30 % and 5–15 % of the general population, respectively [1–3]. Both individuals with insomnia and individuals with migraine experience a limitation of functions and a decrease in quality of life(QOL) due to their symptoms [4–6]. Recent studies have revealed that both conditions imposed a huge amount of personal and social burdens [4, 7].

A close association between insomnia and migraine has been described in previous population-based studies [8–16]. In cross-sectional studies, individuals with migraine had an increased risk of having insomnia [odds ratio (OR) = 1.4–2.6] compared to non-migraineurs and individuals with insomnia had a higher risk of having migraine (OR = 1.5–1.7) compared to individuals without insomnia [8, 11–16]. Longitudinal studies also showed an increase risk [relative risk (RR) = 1.7] for having insomnia among individuals with migraine after 11 years [9]. The association was stronger for those with high frequency migraine. Conversely, individuals with insomnia showed an increased risk of having migraine at 11-year follow-up (RR = 1.7) [10].

Probable migraine (PM) is a migrainous headache fulfilling all but one of the criteria for migraine [17]. Probable migraine was reported to be a common subtype of migraine, with a 1-year prevalence rate ranging from 4.3 to 14.6 % according to the previous population-based studies [18–20]. PM is a common headache type for visiting doctors in neurology department [21]. Individuals with PM often experienced headache-related disability and decreased QOL like migraine [18, 19]. Therefore, PM is an important type of headache in clinical practice.

Although insomnia appears to be closely associated with migraine, the association between insomnia and PM has rarely been reported. The Korean Headache-Sleep Study (KHSS) was a population-based survey regarding headache type and sleep and provided an opportunity to evaluate the association between insomnia and PM. In the present study, we 1) described the prevalence of insomnia, migraine and PM across a general population-based sample; 2) compared the prevalence of insomnia between migraine and PM; and 3) assessed the impact of insomnia in clinical characteristics of migraine and PM using the data from KHSS.

Methods

Survey

We used data from the KHSS in the present study. The KHSS was a nationwide, cross-sectional survey regarding headache types, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and sleep status among the adult population aged 19–69 years. The study design and methods of KHSS have been previously described in detail [22]. Briefly, we used a 2-stage clustered random sampling method for all Korean territories except Jeju-do, proportional to the population distribution. All interviewers were employees of Gallup Korea and had previously experience with social survey interviewing. The survey was conducted by door-to-door visits and face-to-face interviews from November 2011 to January 2012. The study was approved by the institutional review board/ethics committee of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid out in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments [23]. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before each interview.

Assessment of migraine and PM

Diagnoses of migraine and PM were based on criteria A to D for migraine without aura (code 1.1) in the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2) [A, at least five attacks; B, attack duration of 4–72 h; C, any 2 of the 4 typical headache characteristics (i.e., unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate-to-severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or caused by routine physical activity); and D, attacks associated with at least one of the following: nausea, vomiting, or both photophobia and phonophobia] [17]. Subjects who met all of these criteria were considered to have migraine, whereas subjects who met all criteria except one were considered to have PM. Cases with headaches that met the criteria for both PM and tension-type headaches did not receive a PM diagnosis, as per ICHD-2. Because migraine and PM with aura (codes 1.2.1 and 1.6.2, respectively) are difficult to document using the questionnaire method, we did not evaluate aura [24]. Accordingly, these conditions were classified as migraine and PM in the present study.

Assessment of insomnia

We used the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) to diagnose and classify insomnia among subjects. The ISI is a brief self-reported questionnaire that measures the patient’s perception of insomnia severity [25]. The ISI is composed of 7 items that evaluate various aspects of insomnia symptoms. Each ISI item was rated on a scale of 0–4. The total ISI score were divided into 4 categories: 0–7, no clinically significant insomnia; 8–14, subthreshold insomnia; 15–21: moderate insomnia; and 22–28: severe insomnia. If a participant’s ISI score was 15.5 or more, she/he was diagnosed as having insomnia. The Korean version of ISI was previously validated with good sensitivity and specificity and showed a 15.5 cut-off score for discriminating patients with insomnia [26].

Assessment of anxiety and depression

We used the Goldberg Anxiety Scale (GAS) to diagnose anxiety among subjects. This scale comprises four screening items and five supplementary items [27, 28]. Subjects who answered positively for two or more screening items and five or more of all scale items were classified as having anxiety. The Korean version of the scale has an 82.0 % sensitivity and 94.4 % specificity for diagnosing anxiety [28].

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9(PHQ-9) was used to diagnose depression [29]. Subjects who had scores of 10 or more on this measure were considered to have depression. The Korean version of PHQ-9 has an 81.1 % sensitivity and 89.9 % specificity [30].

Analyses

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate the normality of the distribution; after the normality was confirmed, we utilized Student’s t-test and Chi-square test for comparison of prevalence rates where appropriate. If the normality of the distribution was not confirmed, we used Mann–Whitney U test. Multiple linear regression analysis with stepwise selection was used to evaluate contributing factors for ISI score among patients with PM. A significance level of p < 0.05 was set for all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 22.0 (SPSS 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

As with most survey sampling designs, there were missing data (resulting from non-response) for several variables. All of the reported results are based on the available data; as such, the total numbers of some variables diverge from 2695 because of missing data for that particular variable. Imputation techniques were not used because we wanted to minimize non-response effects [31].

Results

Survey

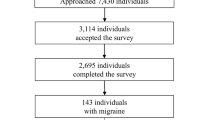

Interviewers approached 7430 individuals. Although three thousand one hundred and fourteen agreed to participate in the survey (rejection rate 58.1 %), 419 individuals withdrew from participation in the interview. Overall, 2695 subjects completed the survey (cooperation rate 36.3 %; Fig. 1). We found no significant differences in the distributions of age, gender, size of residential area, and educational level from those of the general population of Korea (Table 1).

Prevalence of migraine, PM and insomnia

Of the 2695 subjects, 143 (5.3 %) were classified as having migraine and 379 (14.1 %) were classified as having PM during the previous year. Among participants, 333 (12.4 %) had subthreshold insomnia, 83 (3.1 %) had moderate insomnia and 26 (1.0 %) had severe insomnia. Ninety six (3.6 %) reported ≥ 15.5 ISI score and were classified as having insomnia (Table 1).

Prevalence and severity of insomnia among subjects with migraine and PM

Thirteen (9.1 %) subjects with migraine and 31 (8.2 %) subjects with PM were diagnosed as having insomnia. The prevalence of insomnia among subjects with PM was not significantly different compared to those with migraine (p = 0.860). Compared to non-headache controls (1.8 %), the prevalence of insomnia among subjects with migraine [OR = 5.6, 95 % confidence interval (CI) = 2.8–11.2, p < 0.001] and PM (OR = 5.0, 95 % CI = 2.9–8.5, p < 0.001) was significantly higher. Subjects with migraine had higher ISI score compared to subjects with PM (6.8 ± 5.8 vs. 5.5 ± 5.8, p = 0.012). The proportion of severe insomnia (2.8 % vs. 2.4 %, p = 0.782) and moderate insomnia (6.3 % vs. 7.1 %, p = 0.739) was not significantly different between migraine and PM. However, the proportion of subclinical insomnia was higher among subjects with migraine compared to those with PM (28.7 % vs. 16.4 %, p = 0.002) (Fig. 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects with migraine and PM according to the presence of insomnia

Subjects with migraine and PM who had insomnia showed significantly higher GAS score and PHQ-9 score compared to those without insomnia. However, sociodemographic variables such as age, proportion of gender, size of residential and education level were not different according to the presence of insomnia (Table 2).

Headache characteristics of migraine and PM according to the presence of insomnia

The median and 25–75 % interquantile range values of the headache frequency, Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score for headache intensity and Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) score were shown in Table 3. Subjects with migraine and PM who had insomnia showed significantly higher headache frequencies per month [migraine: 4.0, (2.0–11.0) vs. 1.0 (0.3–4.0), p = 0.004; PM: 2.0 (0.4–4.0) vs. 1.0 (0.3–2.0), p = 0.004] and HIT-6 scores [migraine: 65.0 (59.5–71.5) vs. 52.0 (47.0–60.0), p < 0.001; PM: 54.0 (48.0–62.0) vs. 45.5 (42.0–52.0), p < 0.001] compared to those without insomnia. Subjects with PM who had insomnia showed significantly higher VAS score for headache intensity [PM: 6.0 (5.0–7.0) vs. 5.0 (4.0–6.0), p < 0.001) compared to those without insomnia, but subjects with migraine who had insomnia [migraine: 7.0 (5.5–8.5) vs. 6.0 (5.0–7.0), p = 0.076] did not show significantly different VAS score compared to those without insomnia.

Multiple linear regression analyses for contributing factors for ISI score in subjects with PM

We performed the multiple linear regression analyses of clinical variables including sociodemographic variables (age, gender, size of residential area, educational level), GAS score, PHQ-9 score, headache frequency and VAS score to evaluate the contributing factors for ISI score (Table 4). The strongest contributing factor was PHQ-9 score (β = 0.530, p < 0.001), followed by GAS score (β = 0.268, p < 0.001), headache frequency (β = 0.119, p < 0.001) and VAS score (β = 0.076, p = 0.026) for headache intensity.

Discussion

The main findings in the present study are as follows: 1) The prevalence of migraine, PM and insomnia in the Korea population was 5.3, 14.1 and 3.6 %, respectively; 2) The prevalence of insomnia among subjects with PM (8.2 %) was not significantly different compared to that among subjects with migraine (9.1 %); 3) Headache frequency and HIT-6 score of subjects were higher among migraine and PM subjects with insomnia compared to those without insomnia.

The 1-year prevalence of migraine (5.3 %) in the present study was lower than in previous studies from European (10–25 %) and North American (9–16 %) countries [1]. However, the 1-year prevalence of migraine in Asian countries was 4.7 to 9.1 %, which were lower compared to that in European and North American studies [32]. The migraine prevalence in our study was similar to previous studies in Asian countries.

The 1-year prevalence rate of PM was 14.1 % in the present study. Previous epidemiological studies have reported 1-year prevalence rates of PM ranging from 4.3 to 14.6 %. Thus, the prevalence rate of PM in the present study was similar to those in the previous studies [18, 20, 33–36].

The prevalence of insomnia (≥15.5 ISI score) in the present study was 3.6 %. Insomnia prevalence has been previously reported, ranging from 15.3 to 22.8 % in Asian countries including Korea [37–39]. These findings are inconsistent with the present study. This may reflect different insomnia diagnostic criteria. Most previous population-based studies about insomnia probed insomnia symptoms by asking whether subjects had difficult falling asleep, staying asleep and waking too early in the morning. A previous population-based study reported prevalence of insomnia symptoms at least three nights per week was 17.0 %, but insomnia disorder prevalence based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV criteria was 5.0 % in this study [39].

Although the prevalence rate of insomnia was not significantly different between subjects with migraine and PM, the ISI score was significantly different between the two groups in the present study. The difference was associated with the higher prevalence of subthreshold insomnia (8 ≤ ISI score ≤ 14) among subjects with migraine compared to those with PM. The prevalence rate of insomnia in subjects with migraine and PM was higher compared to non-headache controls in the present study. The finding agrees with findings in previous studies concerning the association between headache and insomnia [3]. Cross-sectional studies showed that headache or migraine had increased ORs compared to non-headache controls and longitudinal studies showed bidirectional comorbidity of two conditions: subjects with insomnia showed an increased risk for headache at 11-year follow up and vice versa [10, 40].

A few studies have addressed the relationship between PM and insomnia among children. Children with adult-like migraine had a higher prevalence of sleep disorders compared to non-headache controls (disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep; migraine 37.1 % vs controls 9.2 %, disorders of arousals; migraine 59.3 % vs controls 10.2 %) [41]. Sleep disorders in infancy could be good predictors for the development of headache [42].

In the present study demonstrated that depression (PHQ-9 score), anxiety (GAD-7 score), headache frequency and headache intensity (VAS score) were independently associated with insomnia (ISI score) among individuals with PM (Table 4). This finding was similar to findings in the previous studies among migraineurs. A study including 78 migraineurs and 208 healthy controls revealed that sleep quality and headache frequency was significantly associated after adjusting anxiety and depression [43]. Another study demonstrated that migraineurs had more sleep problems than healthy controls even after adjusting lifetime anxiety and depression [44].

In the present study, headache frequency and HIT-6 score were higher in migraine and PM subjects with insomnia than in those without insomnia. Since a high headache frequency is one risk factor for chronification of headaches, our finding suggests that insomnia may be associated with the chronification of migraine and PM. We also noted that insomnia was associated with a higher HIT-6 score in subjects with migraine and PM. This finding may imply an increased burden of migraine and PM with the presence of insomnia [45]. Physicians should evaluate accompanying insomnia in subjects with migraine and PM. Careful investigation of the main causes of insomnia including psychiatric co-morbidity is also necessary.

This study has some limitations. First, although the questionnaire in this study was validated for migraine, it was not specifically validated for PM. However, the questionnaire itself was based on ICHD-2 and PM was classified based on the ICHD-2 diagnostic criteria. Second, although this study is population-based and had low sampling error, its statistical power was limited in terms of examining the subgroups. In other words, some results might not have reached statistical significance in subgroup analysis because of the limited sample size.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. First, our study was based on clustered random sampling proportional to the Korean population distribution with low sampling error. This condition allowed us to accurately investigate the prevalence of insomnia, migraine, and PM among the Korean adult population. Second, this study explored the relation between PM and insomnia. This relation has been rarely studied. Third, we investigated both anxiety and depression, which are common comorbidities among subjects with insomnia and migraine, and assessed the effect of anxiety and depression in the association of insomnia with migraine and PM. Balancing the limitations and strengths, we believe that the present study accurately describes the association between insomnia and PM in comparison with migraine.

Conclusions

The prevalence rate of insomnia in individuals with PM is not significantly different compared to those with migraine. Insomnia aggravates headache symptoms among individuals with PM as well as among individuals with migraine.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV

- HIT-6:

-

Headache Impact Test-6

- ICHD:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- ISI:

-

Insomnia severity index

- KHSS:

-

Korean Headache-Sleep Study

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- PM:

-

Probable migraine

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- GAS:

-

Goldberg Anxiety Scale

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- VAS:

-

Visual Analogue Scale.

References

Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, Steiner T, Zwart JA (2007) The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 27(3):193–210

Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Merette C (2006) Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med 7(2):123–130

Uhlig BL, Engstrom M, Odegard SS, Hagen KK, Sand T (2014) Headache and insomnia in population-based epidemiological studies. Cephalalgia 34(10):745–751

Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Gregoire JP, Savard J, Baillargeon L (2009) Insomnia and its relationship to health-care utilization, work absenteeism, productivity and accidents. Sleep Med 10(4):427–438

Bolge SC, Doan JF, Kannan H, Baran RW (2009) Association of insomnia with quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment. Qual Life Res 18(4):415–422

Leonardi M, Steiner TJ, Scher AT, Lipton RB (2005) The global burden of migraine: measuring disability in headache disorders with WHO’s Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). J Headache Pain 6(6):429–440

Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, Buse DC, Kawata AK, Manack A, Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB (2011) Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 31(3):301–315

Ødegård SS, Engstrøm M, Sand T, Stovner LJ, Zwart J-A, Hagen K (2010) Associations between sleep disturbance and primary headaches: the third Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. J Headache Pain 11(3):197–206

Ødegård SS, Sand T, Engstrøm M, Stovner LJ, Zwart JA, Hagen K (2011) The Long‐Term Effect of Insomnia on Primary Headaches: A Prospective Population‐Based Cohort Study (HUNT‐2 and HUNT‐3). Headache: J Head Face Pain 51(4):570–580

Ødegård SS, Sand T, Engstrøm M, Zwart J-A, Hagen K (2013) The impact of headache and chronic musculoskeletal complaints on the risk of insomnia: longitudinal data from the Nord-Trøndelag health study. J Headache Pain 14(1):1–10

Sutton DA, Moldofsky H, Badley EM (2001) Insomnia and health problems in Canadians. Sleep 24(6):665–670

Sivertsen B, Krokstad S, Overland S, Mykletun A (2009) The epidemiology of insomnia: associations with physical and mental health. The HUNT-2 study. J Psychosom Res 67(2):109–116

Lucchesi LM, Speciali JG, Santos-Silva R, Taddei JA, Tufik S, Bittencourt LR (2010) Nocturnal awakening with headache and its relationship with sleep disorders in a population-based sample of adult inhabitants of Sao Paulo City, Brazil. Cephalalgia 30(12):1477–1485

Budhiraja R, Roth T, Hudgel DW, Budhiraja P, Drake CL (2011) Prevalence and polysomnographic correlates of insomnia comorbid with medical disorders. Sleep 34(7):859–867

Huang GB, Yao LT, Hou JX, Zhang ZJ, Xin YT, Wu XY, Lu GY, Chen ZQ, Huang JP (2013) Epidemiology of migraine in the She ethnic minority group in Fujian province, China. Neurol Res 35(7):684–692

Lateef T, Swanson S, Cui L, Nelson K, Nakamura E, Merikangas K (2011) Headaches and sleep problems among adults in the United States: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication study. Cephalalgia 31(6):648–653

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache S (2004) The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 24(Suppl 1):9–160

Lanteri-Minet M, Valade D, Geraud G, Chautard MH, Lucas C (2005) Migraine and probable migraine--results of FRAMIG 3, a French nationwide survey carried out according to the 2004 IHS classification. Cephalalgia 25(12):1146–1158

Kim BK, Chung YK, Kim JM, Lee KS, Chu MK (2013) Prevalence, clinical characteristics and disability of migraine and probable migraine: a nationwide population-based survey in Korea. Cephalalgia 33(13):1106–1116

Silberstein S, Loder E, Diamond S, Reed ML, Bigal ME, Lipton RB, Group AA (2007) Probable migraine in the United States: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Cephalalgia 27(3):220–229

Kim BK, Cho SJ, Kim BS, Sohn JH, Kim SK, Cha MJ, Song TJ, Kim JM, Park JW, Chu MK, Park KY, Moon HS (2016) Comprehensive Application of the International Classification of Headache Disorders Third Edition, Beta Version. J Korean Med Sci 31(1):106–113

Cho SJ, Chung YK, Kim JM, Chu MK (2015) Migraine and restless legs syndrome are associated in adults under age fifty but not in adults over fifty: a population-based study. J Headache Pain 16:554

World Medical A (2001) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ 79(4):373–374

Stang PE, Osterhaus JT (1993) Impact of migraine in the United States: data from the National Health Interview Survey. Headache 33(1):29–35

Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM (2001) Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2(4):297–307

Cho YW, Song ML, Morin CM (2014) Validation of a Korean version of the insomnia severity index. J Clin Neurol 10(3):210–215

Goldberg D, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, Grayson D (1988) Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ 297(6653):897–899

Lim JY, Lee SH, Cha YS, Park HS, Sunwoo S (2001) Reliability and validity of anxiety screening scale. J Korean Acad Fam Med 22(8):1224–1232

Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, Burchell CM, Orleans CT, Mulrow CD, Lohr KN (2002) Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 136(10):765–776

Choi HS, Choi JH, Park KH, Joo KJ, Ga H, Ko HJ, Kim SR (2007) Standardization of the Korean version of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 as a screening instrument for major depressive disorder. J Korean Acad Fam Med 28(2):114–119

Rubin DB, Little RJ (2002) Statistical analysis with missing data. J Wiley & Sons, Hoboken

Peng KP, Wang SJ (2014) Epidemiology of headache disorders in the Asia-pacific region. Headache 54(4):610–618

Rains JC, Penzien DB, Lipchik GL, Ramadan NM (2001) Diagnosis of migraine: empirical analysis of a large clinical sample of atypical migraine (IHS 1.7) patients and proposed revision of the IHS criteria. Cephalalgia 21(5):584–595

Bigal ME, Kolodner KB, Lafata JE, Leotta C, Lipton RB (2006) Patterns of medical diagnosis and treatment of migraine and probable migraine in a health plan. Cephalalgia 26(1):43–49

Patel NV, Bigal ME, Kolodner KB, Leotta C, Lafata JE, Lipton RB (2004) Prevalence and impact of migraine and probable migraine in a health plan. Neurology 63(8):1432–1438

Vukovic V, Plavec D, Pavelin S, Janculjak D, Ivankovic M, Demarin V (2010) Prevalence of migraine, probable migraine and tension-type headache in the Croatian population. Neuroepidemiology 35(1):59–65

Yeo BK, Perera IS, Kok LP, Tsoi WF (1996) Insomnia in the community. Singapore Med J 37(3):282–284

Kim K, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Liu X, Ogihara R (2000) An epidemiological study of insomnia among the Japanese general population. Sleep 23(1):41–47

Ohayon MM, Hong SC (2002) Prevalence of insomnia and associated factors in South Korea. J Psychosom Res 53(1):593–600

Sivertsen B, Lallukka T, Salo P, Pallesen S, Hysing M, Krokstad S, Simon O (2014) Insomnia as a risk factor for ill health: results from the large population-based prospective HUNT Study in Norway. J Sleep Res 23(2):124–132

Esposito M, Roccella M, Parisi L, Gallai B, Carotenuto M (2013) Hypersomnia in children affected by migraine without aura: a questionnaire-based case–control study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 9:289–294

Dosi C, Riccioni A, Della Corte M, Novelli L, Ferri R, Bruni O (2013) Comorbidities of sleep disorders in childhood and adolescence: focus on migraine. Nat Sci Sleep 5:77–85

Walters AB, Hamer JD, Smitherman TA (2014) Sleep disturbance and affective comorbidity among episodic migraineurs. Headache 54(1):116–124

Vgontzas A, Cui L, Merikangas KR (2008) Are sleep difficulties associated with migraine attributable to anxiety and depression? Headache 48(10):1451–1459

Sauro KM, Rose MS, Becker WJ, Christie SN, Giammarco R, Mackie GF, Eloff AG, Gawel MJ (2010) HIT-6 and MIDAS as measures of headache disability in a headache referral population. Headache 50(3):383–395

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Yejie Yun, Daewon Foreign Language High School, Seoul, Republic of Korea, for improving the use of English in the manuscript, and Gallup Korea for providing technical support for the Korean Headache-Sleep Study.

Funding

This Study was Supported by a 2011-Grant from Korean Academy of Medical Sciences.

Authors’ contributions

JYK conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. SJC conceptualized and collected the data. WJK conceptualized and collected the data. KIY conceptualized and collected the data. CHY conceptualized and collected the data. MKC conceptualized and designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Cho, SJ., Kim, WJ. et al. Insomnia in probable migraine: a population-based study. J Headache Pain 17, 92 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0681-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0681-2