Abstract

The present compilation is the first attempt to generate a comprehensive list of all macrozoobenthic species recorded at least once in the German regions of the North Sea and Baltic Sea including non-indigenous species and freshwater species which occurred in brackish waters (estuaries, bays, fjords etc.). Based on the data of several research institutes and consultancies, the macrozoobenthic species inventory comprises a total of 1.866 species belonging to 16 phyla including 193 threatened species. The most common groups were: malacostracan crustaceans (21%), Polychaeta (19%), and Gastropoda (12%). Even though the two major marine regions are separated by only 50 km of land, the composition of the respective communities was different. The two seas shared only 36.6% of the recorded species which should have profound and far-reaching consequences for conservation purposes. Considering all macroinvertebrates listed 96 species, or the equivalent of 5.2%, were introduced mainly during the last two centuries. Both seas are heavily affected by human activities and are sensitive to climate change displayed by effects on the faunal compositions. The present checklist is an important step to document these changes scientifically and may act as a base for political and management decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing number of publications focusing on the marine biodiversity indicates the imminent need for comprehensive and complete faunal inventories. Such inventories are also required by governance purposes [e.g. implementation of marine protected areas (MPA) or environmental impact assessments (EIA)] and focus primarily on national requirements. A first overview on macrozoobenthic species in German waters of the North and Baltic Seas was compiled by the red list [1] mainly based on historical references and personal communications. Since then, the knowledge on the distribution and occurrence of species has increased rapidly. This is due to the growing number of data by environmental impact studies particularly for offshore wind farms and governmental monitoring supporting the implementation of European directives such as the EU Habitats Directive (HD), the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Among the recently recorded species, the non-indigenous species (NIS) are of special concern [2]. The consideration of freshwater species colonising brackish waters increased the species number of these habitats by one third compared to those listed in the red list [1].

First investigations of the North Sea in the German Bight, apart from many studies at the island of Helgoland [e.g. 3, 4] and several in the Wadden Sea [5,6,7], were done by Metzger [8], Hagmeier [9], Caspers [10] and later on by Ziegelmeier [11], Dörjes [12], Stripp [13], Salzwedel et al. [14], Niermann [15] and Rachor and Nehmer [16]. They were initiated partly by the considerable interest to monitor the state of the benthos with respect to the impacts of the rapid industrial and agricultural developments on the marine environment and they represent the basic temporal and spatial information for the structure of macrozoobenthic communities in the German part of the North Sea. Systematic investigations on marine benthic species in Germany were first initiated in the second half of the nineteenth century. Several major sampling cruises were carried out in the Baltic Sea [e.g. 17,18,19,20,21,22]. In the 1920s, Hagmeier’s investigations on the bottom fauna of the Baltic Sea were mainly motivated by fisheries [23, 24]. Additionally, comprehensive inventories of two major subregions (Arkona Basin and Mecklenburg Bay) were performed by Löwe [25] and Schulz [26]. Historical overviews on benthological studies in the German part of the Baltic Sea are given by Gerlach [27] and Zettler and Röhner [28], of the North Sea by Kröncke and Bergfeld [29].

The current compilation represents the first comprehensive annotated checklist for both marine and brackish habitats within the two major oceanographic regions of German waters. Although both, North and Baltic Sea are semi-enclosed shelf seas which are highly influenced by the North-East Atlantic, they can be considered as distinct oceanographic regions with strong gradients in environmental conditions (especially salinity) from West to East and from off- to inshore. Due to the natural variability within these systems, however, this list must be regarded as a reflection of a current state, most likely being subject to continuous changes. In addition, this unique checklist provides an important tool and a scientifically sound baseline for the implementation of national requirements (e.g. MPA) and international guidelines (e.g. MSFD, WFD and HD) especially with regards to biodiversity aspects.

Materials and methods

Investigation area

All areas considered belong to the German waters of the North and Baltic Seas, including the territorial waters as well as the exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Data collection and analysis were performed separately for both seas and designated sub-regions (see Additional file 1: Appendix 1).

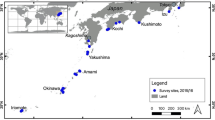

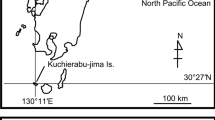

Four subregions were distinguished in the North Sea, depending on their distinctive species assemblages (Fig. 1): (1) estuaries and the Wadden Sea (up to 1 nautical mile beyond the baseline sensu Water Framework Directive); (2) sublittoral zones (from the outer coastline of the Frisian islands to the border of the German EEZ except for subregions 3 and 4); (3) the island of Helgoland as the only natural hard-bottom habitat in the south-eastern North Sea (including “Tiefe Rinne” and “Steingrund”); (4) the Dogger Bank and the central North Sea. The Baltic Sea area was divided into two subregions (Fig. 2): (1) inner coastal waters with estuaries, bays, fjords and lagoons; (2) outer and offshore waters.

Database

Datasets were provided by the following marine research institutes and institutions for environmental observations in Germany:

-

1.

Alfred-Wegener-Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI)

-

2.

Leibniz-Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW)

-

3.

Senckenberg am Meer, Wilhelmshaven

-

4.

Agency for Environment, Conservation and Geology of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (LUNG)

-

5.

Agency for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Areas of Schleswig–Holstein (LLUR)

-

6.

Lower Saxony Water Management, Coastal Defence and Nature Conservation Agency (NLWKN)

-

7.

Agency for Environment and Energy, Nature Conservation of the Hansestadt Hamburg

-

8.

Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH), Hamburg

Private consultancies that contributed to a large extent to the data collection and analyses were:

-

1.

BioConsult Schuchardt & Scholle GBR, Bremen

-

2.

Institute for Applied Ecosystem Research (IfAÖ), Neu Broderstorf

-

3.

MariLim Aquatic Research GmbH, Schönkirchen

The data had been collected according to standard operation procedures such as ICES [30], the standard investigation concept BSH [31] or the ISO standard for infaunal samples [32]. Data were verified for plausibility and nomenclature and quality controlled by independent research institutes. All taxonomic entries provided by different institutions were cross-checked by a group of taxonomic experts which are all certified according to the quality assurance office of the German Federal Environmental Agency, as well as taxonomic experts with expertise and publications on specific taxonomic groups. If needed, taxonomic identification was done again by these taxonomic experts to verify the valid species taxonomy. Finally, taxonomic data were compiled in a large dataset (see Additional file 1: Appendix 1 and Additional file 2: Appendix 2). Each entry was separately evaluated according to its origin, e.g. either from the North or the Baltic Sea and their subregions. Important synonyms and additional taxonomical notes were listed in a separate column. All species were cross-checked with international databases on nomenclature and taxonomy in the following priority: (1) World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), (2) Biological Library (BioLib), (3) Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) and (4) Fauna Europaea Database. All taxonomic entries were linked with the registered species links on the internet platforms (see Additional file 1: Appendix 1).

The present study includes not only marine species but also species occurring in brackish waters since very large areas of the Baltic Sea and the coastal waters as represented by estuaries, bays and fjords are brackish. For that reason some insect groups were considered as well. The species-richest group of insects is represented by the chironomids (89 species with their origin in fresh waters). The data were derived from well-referenced records. Data collections from earlier literature and recent studies were used [see 33, 34] to get an overview of the chironomids species stock.

Results and discussion

Uniqueness and similarity of the sea areas, subregions and faunistic specification

Besides being part of the same large North-East Atlantic system, the German parts of the North and Baltic Sea share some common pressures on the ecosystems (e.g. eutrophication, and ship traffic as vector for NIS) and species composition. However, unique for the shelf seas are, the large intertidal areas of the Wadden Sea, Helgoland as a rocky outpost of boreal fauna, and the strong interrelationships of Baltic inshore waters with limnic habitats. There are several strong riverine inputs (including pollutants and nutrients), especially by the rivers Rhine, Ems, Weser, Elbe and Oder.

Endobenthic communities in the German EEZ of the North Sea were subject to only minor changes in species composition over the past 80 years [35] except for species dominances change and a few distribution shifts between communities documented by Rachor and Nehmer [16] and as well those reported by Salzwedel et al. [14] and Hagmeier [9]. On a larger scale, species composition of the German Bight is comparable to the wider Southern North Sea [e.g. 36, 37]. Small-scale changes or changes over time are primarily linked to the variability of population dynamics, i.e. shifts in the faunal composition due to variable annual and seasonal changes of single species populations, shaping the faunal associations [38]. Furthermore, species occurrences are influenced by gradual shifts of sediments including organic matter on local scales [39] along with typical faunal associations [13, 14, 16, 29, 35, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46] that ultimately increases or depletes species richness locally. Due to the higher sampling effort over the past years, these faunal gradient associations were more extensively sampled than before, reflected in the increased species richness documented in this study.

Estuaries and the Wadden Sea (sub-region 1) of the North Sea (Fig. 1) are characterised by tidal flats, which are in most cases sheltered by the Frisian barrier islands but continuously reshaped by tidal currents. The various habitats of the subregion 1 such as sand and mud flats, sea-grass meadows or beds of blue mussels and oysters [47, 48] support highly diverse benthic fauna associations which serve as productive feeding grounds for young fish and wading birds. The species distributions are determined by sediment and morphological characteristics, as well as by a salinity gradient from the freshwater rivers to the open sea. The habitats within the large estuaries are highly influenced by human activities e.g. ship traffic, harbours, industries and a discharge of nutrients and pollutants [49]. The invertebrate fauna of the Wadden Sea was comprehensively documented in Dankers et al. [50] and chapters therein. According to Buschbaum and Reise [51] and Markert et al. [52], however, the German Wadden Sea has heavily changed due to the presence of NIS (such as e.g. the pacific oyster Magallana gigas) which affect habitat structures and subsequently the biodiversity of the associated fauna.

Sublittoral areas in the North Sea (sub-region 2, Fig. 1) are mainly composed of fine sands with low mud content and a corresponding fauna [53]. At some reefs, sediments are distributed heterogeneously and patchy, covering gradients from muddy fine and coarse sands and from gravel to boulders, each with its own associated diverse species composition. Some dominating groups represent the characterising species of the benthic associations as defined by Salzwedel et al. [14], Rachor and Nehmer [16], Niermann [41], and Neumann et al. [44]. However, due to current construction works for offshore wind farms, the German Bight is subject to an increasing amount of artificial hard substrata, which leads to an increased number of epifaunal and fouling organisms [e.g. 54, 55] competing with benthic in- and epifauna species at the sea floor.

The sub-region 3 around Helgoland (Fig. 1) represents the only larger natural hard bottom of the whole south-eastern North Sea, providing habitats for hard-substrate associated taxa [56,57,58]. This is reflected by its relatively high species richness in the eu- and sublittoral including the depression ‘Tiefe Rinne’ south of Helgoland. This depression is the deepest area of the German Bight with a maximum depth of around 60 m, characterised by secondary hard substrate from dead oyster shells and shell gravel [10, 59]. The habitat is therefore dominated by a hard-bottom fauna such as anthozoans and bryozoans along with co-occurring soft-sediment species. At the edges of the depression, fine silty and muddy sediments are found with their own species composition.

The Dogger Bank, sub-region 4 (Fig. 1) is a sand bank situated between the deeper parts of the central North Sea (up to 70 m water depth in the German EEZ) and the shallower parts of the German Bight (between 30 and 40 m). Thus, it represents an ecologically special area in the German EEZ, forming a transition zone containing species with dominantly northern or southern distributions in the North Sea [60,61,62]. Northern species, however, do not extend further southwards than the northern edge of the Dogger Bank; southern species do not occur further northwards than the 100 m depth contour [43]. Species distribution is mainly influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, stratification (in summer), differing water masses, sediment types and food supply [60, 62, 63], leading to a diverse fauna on the Dogger Bank.

The German part of the Baltic Sea belongs to a transitional zone between the North Sea (via Skagerrak and Kattegat) and the proper Baltic Sea (mainly the large basins of Bornholm and Gotland). In- and outflowing water masses controlled by sea level balance as well as wind and barometric conditions lead to strong variations and to a prominent salinity gradient along the shore of several hundred kilometres length. The western parts (mainly Kiel Bay) are closely connected to the Kattegat and are characterised by salinities between 25 and 30 psu. Within a few hundred kilometres towards the East, the salinity values naturally drop down to 5 psu offshore, and reach freshwater conditions within the inner coastal oligohaline waters. Consequently, the number of marine species in these coastal waters is significantly decreased while the diversity of limnic species increases [64].

The present study divides the German part of the Baltic Sea into two major subregions, the inner coastal waters and the outer or offshore waters (Fig. 2). Depending on the adjacent offshore water region (considering the strong salinity gradient) and the geological evolution of the inner coastal waters (e.g., fjords, lagoons, estuaries), the environmental conditions and the benthic communities vary enormously between the systems. For example, the faunistic inventories of the Flensburg Fjord and the Stettin Lagoon are considerably different. However, both regions show also similarities, especially in the occurrence of numerous freshwater species adapted to brackish water conditions. Some early benthological investigations of such brackish water areas are e.g. the studies of Stammer [65] and Seifert [66]. Recently the efforts increased rapidly regarding the implementation of the Water Framework Directive; all data were included in the present checklist.

Historically important for the offshore region in German Baltic waters are the studies of Meyer and Möbius [67, 68], Hagmeier [23, 24] and Remane [69]. Many others followed and were summarised in Gerlach [27] and Zettler and Röhner [28]. More recently, a number of studies were published, describing and mapping the benthic macrofauna communities in different subbasins of the German Baltic offshore waters [e.g. 70,71,72]. Gogina et al. [73] presented up to 17 benthic communities for the entire Baltic area, each characterised by a distinct species composition. Accordingly, five communities dominate the benthic fauna of the main part of the considered area. On a more fine or detailed scale, the composition of the macrozoobenthos could vary more dramatically depending on specific environmental conditions, and their distribution is therefore more patchy [74].

In total, 1.866 species were recorded for the German parts of North and Baltic Sea (Fig. 3), of which 1.591 species were recognized in the first region, whereas 957 species were reported from the latter one. 682 species occurred in both oceanographic areas (including 126 freshwater species), while 909 species were restricted to the North Sea and 275 species to the Baltic Sea. The number of freshwater species restricted to the North and Baltic Sea were 65 and 159, respectively. Species of marine or freshwater origin are indicated separately for both seas (Fig. 3).

The total of 1.866 species can be assigned to 52 taxonomic groups (Fig. 4) from 16 phyla (Fig. 5). The Polychaeta with 355 registered species is the taxonomic group with the highest species number. Gastropoda with 218 species and Amphipoda with 204 species are the second and third diverse groups. Bivalvia (143 species), Cnidaria (132) and Bryozoa (118 species) contribute more than 100 species, whereas nearly half of the groups contain less than five species (Fig. 4). The phylum with the highest species number is represented by the Arthropoda with 574 species (Fig. 5), followed by the phylum Annelida (470 species), which includes the species-rich taxonomic group of Polychaeta, and by the phylum Mollusca (371 species). More than 75% of the registered species belong to these three phyla. Six of the phyla consist of 26 species in total but less than 10 species each, e.g. constituting only 1.4% of the recorded species. The differences in the species number of phyla may reflect the intensity of taxonomic work within taxonomic groups and the focus of standard monitoring programs. We argue that some of the phyla were hardly considered in regular monitoring programs, similar to cryptic species (see increasing genetic aspects of taxonomical studies) and those of poorly studied groups (e.g. Nemertea).

Taxonomic composition (phyla) of macrozoobenthos in German waters of the North and Baltic Seas. The phylum-level have the same colours as the taxonomic groups in Fig. 4

Non-indigenous species

The introduction of non-indigenous species to European marine waters has increased substantially over the last century due to numerous anthropogenic activities such as the commercial transport of aquaculture species and global shipping [75,76,77]. Due to their large international harbours, the North and Baltic Sea coasts exhibit the highest density of ship traffic world-wide [78], a major cause for the high number of neobiota found in all marine and brackish environments of many European countries [79, 80] including Germany [2]. In order to evaluate and analyse neobiota introductions in the context of marine biodiversity and their effects, an updated and comprehensive species inventory as presented here is of pivotal importance. The inventory species list supports the effort of monitoring neobiota under the recent European Marine Strategy Directive, which includes NIS as a descriptor of ecosystem quality (D2).

In the German Bight, neobiota, especially fouling organisms, occur only locally, but are expected to spread and increase in number due to the large extent of artificial hard substrata that probably act as preferred stepping stones. The continued transfer vectors are the input of foreign aquaculture species or commercial and recreational shipping [77, 82]. The number of NIS in the in- and epifauna in offshore waters of the North and Baltic Sea is comparably low and might not yet have distinct effects on the ecological functioning of the benthos [83,84,85,86]. However, especially in nearshore areas and particularly in harbours, NIS might occur with a high number of species, which has been proven to contribute up to 44% of total species number [87, 88]. As documented for some cases their abundance contributed to more than 90% of all invertebrates collected [e.g. 89].

The most successful taxa regarding introduction and immigration to both oceanographic areas are polychaetes, bivalves and amphipods (Fig. 6). Allochthonous species of all groups were generally present in higher species numbers in the German part of the North Sea than of the Baltic Sea. Regarding their abundance, however, many taxa showed a reverse pattern with higher abundances in the Baltic than in the North Sea. In total, 96 NIS in 17 taxonomic groups were identified of which 88 species occurred in the North Sea and 53 in the Baltic (Fig. 6). There is already a substantial increase to the recent publication by Lackschewitz et al. [2] who reported 88 marine and brackish neozoan while the overview on German Neobiota by Gollasch and Nehring [81] only mentioned 62 neozoan taxa for the North Sea and 34 for the Baltic Sea.

General considerations

For the first time, differences of the benthic species richness of the German North Sea and its estuaries and the Baltic Sea including their brackish water habitats are listed in a comprehensive inventory (see Additional file 1: Appendix 1). As an important part of this inventory, the freshwater species as a faunal component of the brackish areas were considered. For example, a complete and referenced overview for chironomids is provided based on new material and literature. However, a further increase in species number is expected, as literature data in the literature suggest that low-salinity coastal waters may harbour a number of additional taxa not yet recorded. Environmental changes such as climate driven temperature increase might also cause further increase in species numbers or differences in species compositions. Due to the lack of substantial zoogeographical borders such as mountains, currents or climatic zones, the area of the present study is connected to the Atlantic Ocean and thus incoming species from the Atlantic. The presumed number of macrozoobenthic species may probably 20% higher than the one registered at the moment. For example, the current survey confirms a total number of 204 species of amphipod crustaceans for German waters of approx. 250 species which can be expected from adjacent areas [90,91,92]. The absence of many oceanic species is likely to be attributed to the environmental conditions in the North Sea with its comparatively low water temperatures in winter preventing oceanic species from establishing permanent populations in the shallow German Bight. Consequently, warm-temperate and cold-temperate species are uncommon in the German Bight. In the course of climate warming, however, the trend towards mild winters may facilitate the recent range expansion of a growing number of oceanic species to German waters [85, 93,94,95]. Additionally, the trend of an increasing number of newly introduced species within the last two decades [2, 92] needs to be considered. In the long term, these trends are expected to increase in the future.

Abbreviations

- BioLib:

-

Biological Library

- EEZ:

-

exclusive economic zone

- ITIS:

-

Integrated Taxonomic Information System

- NIS:

-

non-indigenous species

- WORMS:

-

World Register of Marine Species

References

Rachor E, Bönsch R, Boos K, Gosselck F, Grotjahn M, Günther C-P, Gusky M, Gutow L, Heiber W, Jantschik P, Krieg H-J, Krone R, Nehmer P, Reichert K, Reiss H, Schröder A, Witt J, Zettler ML. Rote Liste der bodenlebenden wirbellosen Meerestiere. Natursch Biol Vielf. 2013;70(2):81–176.

Lackschewitz D, Reise K, Buschbaum C, Karez R. Neobiota in deutschen Küstengewässern. Eingeschleppte und kryptogene Tier- und Pflanzenarten an der deutschen Nord- und Ostseeküste. Kiel: LLUR SH; 2015.

von Dalla Torre KW. Die Fauna von Helgoland. Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1889.

Metzger A. Nachträge zur Fauna von Helgoland. Zool Jahrb. 1891;5:907–20.

Hagmeier A, Kändler R. Neue Untersuchungen im nordfriesischen Wattenmeer und auf den fiskalischen Austernbänken. Wiss Meeresunters N.F. (Helgoland). 1927;16:1–90.

Wohlenberg E. Die Wattenmeer-Lebensgemeinschaften im Königshafen von Sylt. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters. 1937;1:1–92.

Linke O. Die Biota des Jadebusenwattes. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters. 1939;1:201–338.

Metzger A. Physikalische und faunistische Untersuchungen der Nordsee während des Sommers 1871. Ber Comm Wiss Unters Dt Meere Berlin. 1873;1:165–76.

Hagmeier A. Vorläufiger Bericht über die vorbereitenden Untersuchungen der Bodenfauna der Deutschen Bucht mit dem Petersen-Bodengreifer. Ber Dt Wiss Komm Meeresf. 1925;1:247–72.

Caspers H. Die Bodenfauna der Helgoländer Tiefen Rinne. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters. 1939;2:1–112.

Ziegelmeier E. Macrobenthos investigations in the eastern part of the German Bight from 1950 to 1974. Rapp Proc-Verb Réun Cons Int Explor Mer. 1978;172:432–44.

Dörjes J. Das Makrobenthos. Senckenberg Leth. 1968;49:261–309.

Stripp K. Die Assoziationen des Benthos in der Helgoländer Bucht. Veröff Inst Meeresf Bremerhaven. 1969;12:95–142.

Salzwedel H, Rachor E, Gerdes D. Benthic macrofauna communities in the German Bight. Veröff Inst Meeresf Bremerhaven. 1985;20:199–267.

Niermann U. Macrobenthos of the south-eastern North Sea during 1983–1988. Ber Biol Anst Helgol. 1997;13:1–144.

Rachor E, Nehmer P. Erfassung und Bewertung ökologisch wertvoller Lebensräume in der Nordsee. BfN-Projekt-Bericht; 2003.

Arnold C, Lenz H. Erster allgemeiner Bericht über die im Jahre 1872 angestellten zoologisch-botanischen Untersuchungen der Travemünder Bucht. Lübeckische Blätter. 1873;15(39):213–6.

Lenz H. Die wirbellosen Thiere der Travemünder Bucht. Jahresber Komm wiss Unters dt Meere Kiel (Anhang 1 zum. Jahresbericht. 1874;1875(4):1–24.

Lenz H. Die wirbellosen Thiere der Travemünder Bucht. Teil I. Ber Comm Wiss Unters Dt Meere Kiel (4.- 6. Jahrgang, Anhang I zum Jahresbericht 1874/1875). 1878;3:1–24.

Lenz H. Die wirbellosen Thiere der Travemünder Bucht. Theil II. Resultate der im Auftrage der Freien und Hanse-Stadt Lübeck angestellten Schleppnetzuntersuchungen. Ber Comm Wiss Unters Dt Meere Kiel (7. bis 11. Jg). 1882;4(1. Abt):169–80.

Möbius K. Die wirbellosen Thiere der Ostsee. Ber Comm Wiss Unters Dt Meere Kiel. 1873;1:97–144.

Möbius K. Nachtrag zu dem im Jahre 1873 erschienenen Verzeichnis der wirbellosen Thiere der Ostsee. Ber Comm Wiss Unters Dt Meere Kiel (7. bis 11. Jg). 1884;4(3. Abt):61–70.

Hagmeier A. Die Arbeiten mit dem Petersenschen Bodengreifer auf der Ostseefahrt 1925. Vorläuf Mitt Ber Dt Wiss Komm Meeresf N.F. 1926;2:304–7.

Hagmeier A. Die Bodenfauna der Ostsee im April 1929 nebst einigen Vergleichen mit April 1925 und Juli 1926. Vorläufige Übersicht über Untersuchungen auf dem Reichsforschungsdampfer „Poseidon“. Ber Dt Wiss Komm Meeresf. 1930;5:157–73.

Löwe FK. Quantitative Benthosuntersuchungen in der Arkonasee. Mitt Zool Mus Berlin. 1963;39:247–349.

Schulz S. Benthos und Sediment in der Mecklenburger Bucht. Beitr Meereskd. 1969;24(25):15–55.

Gerlach S. Checkliste der Fauna der Kieler Bucht und eine Bibliographie zur Biologie und Ökologie der Kieler Bucht. In: Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde (Hrsg.), Die Biodiversität in Nord- und Ostsee, Band 1. 2000;1247:1–376.

Zettler ML, Röhner M. Verbreitung und Entwicklung des Makrozoobenthos der Ostsee zwischen Fehmarnbelt und Usedom - Daten von 1839 bis 2001. In: Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde, editor. Die Biodiversität in Nord- und Ostsee, Band 3. 2004;1421:1–175.

Kröncke I, Bergfeld C. North Sea benthos: a review. Senckenberg Marit. 2003;33:205–68.

Rumohr H. Soft bottom macrofauna: collection, treatment, and quality assurance of samples. ICES Tech Environ Sci. 1999;27:1–19.

BSH. Standard investigation of the impacts of offshore wind turbines on the marine environment (StUK4), Bundesamt für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrographie (BSH). Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency, Hamburg und Rostock; 2013.

ISO. Water quality—guidelines for quantitative sampling and sample processing of marine soft-bottom macrofauna. Geneva: International Standard (ISO); 2005.

Orendt C, Dettinger-Klemm A, Spies M. Entwicklung von Bestimmungsschlüsseln für das marine Monitoring. Teilvorhaben: Bestimmungsschlüssel für Larven der Chironomidae deutscher Brackwassergebiete. Umweltforschungsplan des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit. Umweltbundesamt Berlin FKZ: 370725201; 2011.

Orendt C, Dettinger-Klemm A, Spies M. Bestimmungsschlüssel für die Larven der Chironomidae (Diptera) der Brackgewässer Deutschlands und angrenzender Gebiete. Berichte der Qualitätssicherungsstelle des Bund/Länder-Messprogramms für die Meeresumwelt von Nord- und Ostsee Nr. 2015;1:1–214.

Kröncke I, Reiss H, Eggleton JD, Aldridge J, Bergman MJN, Cochrane S, Craeymeersch JA, Degraer S, Desroy N, Dewarumez JM, Duineveld GCA, Essink K, Hillewaert H, Lavaleye MSS, Moll A, Nehring S, Newell R, Oug E, Pohlmann T, Rachor E, Robertson M, Rumohr H, Schratzberger M, Smith R, Vanden Berghe E, van Dalfsen J, van Hoey G, Vincx M, Willems W, Rees HL. Changes in North Sea macrofauna communities and species distribution between 1986 and 2000. Est Coast Shelf Sci. 2011;94:1–15.

Van Hoey G, Vincx M, Degraer S. Small- to large-scale geographical patterns within the macrobenthic Abra alba community. Est Coast Shelf Sci. 2005;64:751–63.

Rachor E, Reiss H, Degrear S, Duineveld GCA, van Hoey G, Lavaleye M, Willems W, Rees HL. Structure, distribution, and characterizing species of North Sea macro-zoobenthos communities in 2000. ICES Coop Res Rep. 2007;288:46–59.

Neumann H, Reiss H, Rakers S, Ehrich S, Kröncke I. Temporal variability of southern North Sea epifauna communities after the cold winter 1995/1996. ICES J Mar Sci. 2009;66:2233–43.

Fiorentino D, Pesch R, Günther C-P, Gutow L, Holstein J, Dannheim J, Ebbe B, Bildstein T, Schroeder W, Schuchardt B, Brey T, Wiltshire K. A ‘fuzzy clustering’ approach to conceptual confusion: how to classify natural ecological associations. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2017;584:17–30.

Dyer MF, Fry WG, Fry PD, Cranmer GJ. Benthic regions within the North Sea. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 1983;63:683–93.

Niermann U, Bauerfeind E, Hickel W, von Westernhagen H. The recovery of benthos following the impact of low oxygen content in the German Bight. Neth J Sea Res. 1990;25:215–26.

Heip CHR, Basford D, Craeymeersch JA, Dewarumez J-M, Doerjes J, De Wilde PAJ, Duineveld G, Eleftheriou A, Herman PMJ, Niermann U, Kingston P, Kuenitzer A, Rachor E, Rumohr H, Soetaert K. Trends in biomass, density and diversity of North Sea macrofauna. ICES J Mar Sci. 1992;49:13–22.

Künitzer A, Basford D, Craeymeersch JA, Dewarumez J-M, Doerjes J, Duineveld GCA, Eleftheriou A, Heip CHR, Herman P, Kingston P, Niermann U, Rachor E, Rumohr H, De Wilde PAJ. The benthic infauna of the North Sea: species distribution and assemblages. ICES J Mar Sci. 1992;49:127–43.

Neumann H, Reiss H, Ehrich S, Sell A, Panten K, Kloppmann M, Wilhelms I, Kröncke I. Benthos and demersal fish habitats in the German Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the North Sea. Helgol Mar Res. 2013;67:445–59.

Neumann H, Diekmann R, Kröncke I. The influence of habitat characteristics and fishing effort on functional composition of epifauna in the south-eastern North Sea. Est Coast Shelf Sci. 2016;169:182–94.

Neumann H, Diekmann R, Emeis K-C, Kleeberg U, Moll A, Kröncke I. Full-coverage spatial distribution of epibenthic communities in the south-eastern North Sea in relation to habitat characteristics and fishing effort. Mar Environ Res. 2017;130:1–11.

Schückel U, Kröncke I. Temporal changes in intertidal macrofauna communities over eight decades: a result of eutrophication and climate change. Est Coast Shelf Sci. 2013;117:210–8.

Schückel U, Beck M, Kröncke I. Spatial variability in structural and functional aspects of macrofauna communities and their environmental parameters in the Jade Bay (Wadden Sea Lower Saxony, southern North Sea). Helgol Mar Res. 2013;67:121–36.

Witt J. Analysing brackish benthic communities of the Weser estuary: spatial distribution, variability and sensitivity of estuarine invertebrates. Dissertation University Bremen; 2004.

Dankers N, Kühl H, Wolff WJ. Invertebrates of the Wadden Sea. Final report of the Wadden Sea Working Group. Leiden: Stichting; 1981.

Buschbaum C, Reise K. Neues Leben im Weltnaturerbe Wattenmeer. Globalisierung unter Wasser. Biol Unserer Zeit. 2010;40:202–10.

Markert A, Wehrmann A, Kröncke I. Recently established Crassostrea-reefs vs. native Mytilus-beds: differences in habitat engineering affects the macrofaunal communities (Wadden Sea of Lower Saxony, southern German Bight). Biol Inv. 2010;12:15–32.

Kröncke I, Stoeck T, Wieking G, Palojaervi A. Relationship between structural and trophic aspects of microbial and macrofaunal communities in different areas of the North Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;282:13–31.

Inger R, Attrill MJ, Bearhop S, Broderick AC, James Grecian W, Hodgson DJ, Mills C, Sheehan E, Votier SC, Witt MJ, Godley BJ. Marine renewable energy: potential benefits to biodiversity? An urgent call for research. J Appl Ecol. 2009;46:1145–53.

Lindeboom HJ, Kouwenhoven HJ, Bergman MJN, Bouma S, Brasseur S, Daan R, Fijn RC, de Haan D, Dirksen S, van Hal R, Lambers RHR, ter Hofstede R, Krijgsveld KL, Leopold M, Scheidat M. Short-term ecological effects of an offshore wind farm in the Dutch coastal zone; a compilation. Environ Res Lett. 2011;6:035101.

Kühne S, Rachor E. The macrofauna of a stony sand area in the German Bight (North Sea). Helgol Meeresunters. 1996;50:433–52.

Bartsch I, Kuhlenkamp R. The marine macroalgae of Helgoland (and North Sea): an annotated list of records between 1845 and 1999. Helgol Mar Res. 2000;54:160–89.

Bartsch I, Tittley I. The rocky intertidal biotopes of Helgoland: present and past. Helgol Mar Res. 2004;58:289–302.

Caspers H. Die Lebensgemeinschaft der Helgoländer Austernbank. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters. 1950;3:119–69.

Kröncke I. Changes in Dogger Bank macrofauna communities in the 20th century caused by fishing and climate. Est Coast Shelf Sci. 2011;94:234–45.

Sonnewald M, Türkay M. The megaepifauna of the Dogger Bank (North Sea): species composition and faunal characteristics 1991–2008. Helgol Mar Res. 2012;66:63–75.

Sonnewald M, Türkay M. Environmental influence on the bottom and near-bottom megafauna communities of the Dogger Bank: a long-term survey. Helgol Mar Res. 2012;66:503–11.

Glémarec M. The benthic communities of the European North Atlantic shelf. Oceanogr Mar Biol Ann Rev. 1973;11:263–89.

Zettler ML, Schiedek D, Glockzin M. Chapter 17: zoobenthos. In: Feistel R, Nausch G, Wasmund N, editors. State and evolution of the Baltic Sea, 1952–2005. A detailed 50-year survey of meteorology and climate, physics, chemistry, biology, and marine environment. Hoboken: Wiley; 2008. p. 517–41.

Stammer HJ. Die Fauna der Ryckmündung, eine Brackwasserstudie. Ztschr Morph Ökol Tiere. 1928;11:36–101.

Seifert R. Die Bodenfauna des Greifswalder Boddens. Ein Beitrag zur Ökologie der Brackwasserfauna. Ztschr Morph Ökol Tiere. 1938;34:221–71.

Meyer HA, Möbius K. Fauna der Kieler Bucht 1. Band: Die Hinterkiemer oder Opisthobranchia. Leipzig: Verlag Wilhelm Engelmann; 1865.

Meyer HA, Möbius K. Fauna der Kieler Bucht 2. Band: Die Prosobranchia und Lamellibranchia. Leipzig: Verlag Wilhelm Engelmann; 1872.

Remane A. Einführung in die zoologische Ökologie der Nord- und Ostsee. In: Grimpe G, Wagler E, editors. Die Tierwelt der Nord- und Ostsee. Band 1a. Leipzig: Geest & Portig; 1940. p. 1–238.

Kube J. The ecology of macrozoobenthos and sea ducks in the Pomeranian Bay. Meereswiss Ber. 1996;18:1–128.

Glockzin M, Zettler ML. Spatial macrozoobenthic distribution patterns in relation to major environmental factors—a case study from the Pomeranian Bay (southern Baltic Sea). J Sea Res. 2008;59:144–61.

Gogina MA, Zettler ML. Diversity and distribution of benthic macrofauna in the Baltic Sea. Data inventory and its use for species distribution modelling and prediction. J Sea Res. 2010;64:313–21.

Gogina M, Nygård H, Blomqvist M, Daunys D, Josefson AB, Kotta J, Maximov A, Warzocha J, Yermakov V, Gräwe U, Zettler ML. The Baltic Sea scale inventory of benthic faunal communities in the Baltic Sea. ICES J Mar Sci. 2016;73:1196–213.

Schiele KS, Darr A, Zettler ML, Friedland R, Tauber F, von Weber M, Voss J. Biotope map of the German Baltic Sea. Mar Poll Bull. 2015;96:127–35.

Wolff WJ. Exotic invaders of the meso-oligohaline zone of estuaries in the Netherlands: why are there so many? Helgol Meeresunters. 1999;52:393–400.

Gollasch S. The importance of ship hull fouling as a vector of species introductions into the North Sea. Biofouling. 2002;18:105–21.

Kuhlenkamp R, Kind B. Introduction of non-indigenous species. In: Salomon M, Markus T, editors. Handbook on marine environment protection—science, impacts and sustainable management. Heidelberg: Springer; 2018. p. 487–516.

Kaluza P, Kölzsch A, Gastner MT, Blasius B. The complex network of global cargo ship movements. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:1093–103.

Gollasch S, Haydar D, Minchin D, Wolff WJ, Reise K. Introduced aquatic species of the North Sea coasts and adjacent brackish waters. In: Rilov G, Crooks J, editors. Biological invasions in marine ecosystems: ecological, management and geographic perspectives. Ecological studies, vol. 204. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. p. 507–28.

Galil BS, Marchini A, Occhipinti-Ambrogi A, Minchin D, Narščius A, Ojaveer H, Olenin S. International arrivals: widespread bioinvasions in European Seas. Ethol Ecol Evol. 2014;26:152–71.

Gollasch S, Nehring S. National checklist for aquatic alien species in Germany. Aquat Inv. 2006;1:245–69.

Gollasch S. Overview on introduced aquatic species in European navigational and adjacent waters. Helgol Mar Res. 2006;60:84–9.

Kröncke I, Reiss H, Dippner JW. Effects of cold winters and regime shifts on macrofauna communities in the southern North Sea. Est Coast Shelf Sci. 2013;119:79–90.

Dannheim J, Holstein J, Brey T. Naturverträgliche Entwicklungen auf See (NavES)—Offshore Forschung: Bereitstellung von Umweltinformationen aus Forschungsvorhaben und aus dem Monitoring von Offshore Windparks—Erweiterung und Aktualisierung des bestehenden Fachinformationssystems und des webbasierten Dienstes für Benthosdaten. Project report; 2015.

Neumann H, de Boois I, Kröncke I, Reiss H. Climate change facilitated range expansion of the non-native Angular crab Goneplax rhomboides into the North Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2013;484:143–53.

Zettler ML, Karlsson A, Kontula T, Gruszka P, Laine A, Herkül K, Schiele K, Maximov A, Haldin J. Biodiversity gradient in the Baltic Sea: a comprehensive inventory of macrozoobenthos data. Helgol Mar Res. 2014;68:49–57.

Nestler S, Schanz, A. Neobiota-Erfassung an ‚Hot Spots‘ der Neubesiedlung in niedersächsischen Küstengewässern. IfAÖ Forschungsbericht im Auftrag der Nationalparkverwaltung Niedersächsisches Wattenmeer; 2016.

Kazmierczak F, Schanz, A. Erfassung und Bewertung nicht einheimischer Arten—Neobiota-in Küstengewässern Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns, IfAÖ Forschungsbericht im Auftrag des Landesamt für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Geologie Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; 2016.

Zettler ML. Population dynamics, growth and production of the neozoon Marenzelleria cf. viridis (Verrill, 1873) (Polychaeta: Spionidae) in a coastal water of the southern Baltic Sea. Aquat Ecol. 1997;31:177–86.

Lincoln RJ. British marine Amphipoda: Gammaridea. London: British Museum (Natural History); 1979.

Schellenberg A. Flohkrebse oder Amphipoda. In: Dahl F, editor. Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meeresteile nach ihren Merkmalen und ihrer Lebensweise. Teil 40, Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1942.

Zettler ML, Zettler A. Marine and freshwater Amphipoda from the Baltic Sea and adjacent territories. In: Dahl F, editor. Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meeresteile nach ihren Merkmalen und ihrer Lebensweise. Teil 83, Harxheim: Conchbooks; 2017.

Franke H-D, Gutow L. Long-term changes in the macrozoobenthos around the rocky island of Helgoland (German Bight, North Sea). Helgol Mar Res. 2004;98:303–10.

Wiltshire KH, Kraberg A, Bartsch I, Boersma M, Franke H-D, Freund J, Gebühr C, Gerdts G, Stockmann K, Wichels A. Helgoland Roads, North Sea: 45 years of change. Est Coasts. 2010;33:295–310.

Beermann J, Franke H-D. A supplement to the amphipod (Crustacea) species inventory of Helgoland (German Bight, North Sea): indication of rapid recent change. Mar Biodivers Rec. 2011;4:e41.

Authors’ contributions

MLZ: summarised the data from different sources, compiled them in a large data-set, verified for plausibility and nomenclature, carried out the data analysis, wrote most parts of the manuscript; JB: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; JD: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; EB: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; MG: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; CPG: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; MG: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; BK: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; IK data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; RK: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; CO: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; ER: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; ANS: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; ALS: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; LS: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript; JW: data cross-check on taxonomy, analysis and interpretation of data; contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank many scientific and technical colleagues for sampling, sorting and storing the macrozoobenthic data in several research institutes and private consultancies. The impulse to compile a species list for the German parts of the North and the Baltic Seas came from the Agency for Environment, Conservation and Geology Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Umweltbundesamt and the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) as a base for the improvement of the red list.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The database used during the current study is available as Appendices 1 (data) and 2 (referred literature) attached to this manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Authors comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1.

Checklist (data table) of all macrozoobenthic species occurring in the investigation area (North Sea, Baltic Sea).

Additional file 2.

References cited and used in the data table (Additional file 1).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zettler, M.L., Beermann, J., Dannheim, J. et al. An annotated checklist of macrozoobenthic species in German waters of the North and Baltic Seas. Helgol Mar Res 72, 5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10152-018-0507-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10152-018-0507-5