Abstract

Inspired by the use of rift-sawn softwood board for covering curved surfaces in Kokerabuki, a traditional Japanese roofing method, we investigated the flexural anisotropy of wood caused by its end-grain orientation. We measured the flexural displacement of softwood species, Chamaecyparis obtusa and Cryptomeria japonica, and hardwood species, Populus suaveolens and Cerasus serrulata. For the softwood species, this was approximately five times longer for the rift-sawn specimens than for the other grain patterns. Using the replica method to measure the softwood tracheid deformation with different flexural displacements, we confirmed the different deformation mechanisms of the tracheid in the flat- and quarter-sawn specimens, and rift-sawn specimens. In the flat- and quarter-sawn woods, on-axis loading was generated, in which the stress was concentrated on the radial and tangential cell walls parallel to the direction of tension or compression. By contrast, in the rift-sawn wood, off-axis loading was generated, in which the stress was evenly distributed throughout the corner cell walls without the wall directly resisting the tensile and compressive forces. We also concluded that the tapered shape of the tracheid walls contributes to the excellent flexibility of rift-sawn softwood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

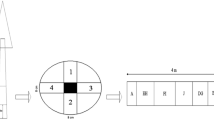

Kokerabuki is a unique Japanese roofing method of stacking thin wood boards. This method is applied to many of the traditional Japanese architectures designated as important cultural properties [1]. Traditional Japanese roofing methods are categorized into several types, such as Kokerabuki, Tokusabuki, and Tochibuki, depending on the thickness of the boards used. The thinnest board (kokera board) (2–3-mm thickness, 9–15-cm width, and about 30-cm length) is used for Kokerabuki (Fig. 1a, b).

Lumber cut from logs is classified into flat- (also called plain-), rift-, and quarter-sawn woods depending on the orientation of the growth ring on the transverse plane; the type of wood produced depends on the cutting method [2]. For kokera boards, quarter- and rift-sawn softwood boards are used (Fig. 1c). Flat-sawn boards are excluded because of their relatively poor dimensional stability; for example, they are susceptible to cupping, whereby moisture gradients deform the board into a concave shape. Rift-sawn boards are mainly used to cover the curved surfaces on roofs. Traditional carpenters were aware, based on empirical knowledge, that rift-sawn boards are more flexible than the other types of board.

Studies of wood’s grain orientation generally concern axial grains, which represent the longitudinal arrangement of wood cells. This is because the mechanical performance of wood is considered to be best in the longitudinal direction [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Moreover, the grain orientation affects the physical and mechanical behavior of wood [9, 10]. For Kokerabuki, however, there are insufficient studies on how end-grain orientation affects thin boards. If physical and mechanical anisotropy is induced by end-grain orientation, it should be considered when designing products based on thin boards. In addition to Kokerabuki, these products include acoustic boards for musical instruments and veneers for wood composites.

In this study, we investigated the flexural anisotropy of softwoods imparted by their end-grain orientation. The flexural performance and tracheid deformation in flat-, rift, and quarter-sawn boards with various displacements were investigated, and the origin of the flexibility of the rift-sawn board is discussed.

Experimental

Materials

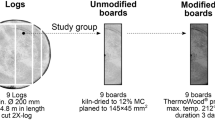

To evaluate the flexural performance of the softwood board, we measured the modulus of elasticity (MOE) and modulus of rupture (MOR) for two softwood species, Chamaecyparis obtusa and Cryptomeria japonica. To compare the flexural behavior between softwood and hardwood species, we also measured the MOE and MOR for two hardwood species, Populus suaveolens and Cerasus serrulata. These diffuse-porous species without broad rays were selected under the consideration that they were more appropriate to compare the flexural behavior with softwoods than ring-porous species with large vessels concentrated in earlywood and diffuse-porous species with broad rays. Typical optical micrographs showing each cross-sectional view are presented in Additional file 1: Fig. S1. The wood samples were air-dried wood provided by the xylarium of Kyoto University. The wood specimens were cut into a size of 100 mm (length) × 10 mm (width) × 3 mm (height) with three grain patterns (flat-, rift-, and quarter-sawn), and five specimens per species and pattern were used for the test. The properties of the specimens are listed in Table 1.

Flexural test

The flexural performance was measured with a three-point bending test using a universal testing machine. The flexural load was applied to the longitudinal–tangential plane for flat-sawn specimens and to the longitudinal–radial plane for rift- and quarter-sawn specimens. The loading rate was 10 mm/minute, the span was 65 mm, and the MOE and MOR were calculated from the following equations, respectively:

where σ is the stress (σ = 3Fl /2wh2), ε is the strain (ε = 6dh / l2), F is the force, Fm is the maximum force, l is the span, w and h are the width and height of the specimen, respectively, and d is the flexural displacement.

Replica method

A replica method was performed to observe the deformation of softwood tracheids in the transverse plane with various flexural displacements [11, 12]. This method duplicates the surface by pressing the softened polyethylene film onto the radial–tangential plane. A polyethylene film with a thickness of 0.1 mm on a slide glass was placed on a heating block at 130 °C ( Fig. 2a). When the film was sufficiently softened, it was placed on the transverse surface of the specimen, fixed to the holder, and pressed on a slide glass with tweezers to duplicate the contact surface between the film and the specimen (Fig. 2b). Then, the cell shape on the transverse plane was observed using an optical microscope (Fig. 2c). A specimen holder with flexural displacements of 2, 5, 8, and 15 mm was used (Fig. 2d). The surfaces of the bent specimens were duplicated and observed using the same procedure.

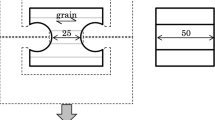

Procedure for obtaining replica images and measuring tracheid deformation. a Softening of polyethylene film on a glass slide using a heating block. b Duplication of the surface of the specimen by pressing the film on the transverse plane. c Observation and capture of replica images using an optical microscope. d Flexural displacement to observe cell deformation. e To assess the cell deformation in the compression and tension parts in d, we measured the ratio of the tangential to radial diameter (T/R) and the diagonal ratio

Tracheid deformation measures

To assess the deformation of tracheids in the transverse plane from the flexural displacements, we measured the ratio of the tangential to radial diameter of the tracheid lumen (T/R ratio) and the ratio of the two diagonal diameters (minimum diameter/maximum diameter) in the tensile and compression parts of the specimen (Fig. 2e). The deformation was measured as the mean value of 10 tracheids, and a series of deformations of the same tracheids were measured at all tested flexural displacements. Because the shape of the tracheids varies in a given specimen, the rate of change (i.e. the ratio at each displacement relative to the initial ratio) in the T/R ratio and the diagonal ratio was calculated.

Results

Flexural properties

The load–displacement curves of two softwoods and two hardwoods are presented in Fig. 3. There were large differences in the flexural stiffness between the rift-sawn softwoods and hardwoods species. A real-time flexural test was exemplified in Additional file 2: Fig. S2. The flexural displacements of the hardwoods were similar for all grain patterns, whereas the displacements of the softwoods were larger for rift-sawn than for other grain patterns. The curves of the flat- and quarter-sawn specimens consisted mostly of elastic regions, and the specimens fractured after a short plastic region. By contrast, the rift-sawn specimens not only had a long elastic region with a smaller flexural load than the other patterns but also had a longer plastic region. The rift-sawn specimens of Chamaecyparis obtusa and Cryptomeria japonica had a displacement of more than 15 mm—about five times higher than the other patterns.

The differences in the MOE and MOR of the species tested were consistent with their density differences. For a given species, however, the differences in flexural behavior among the different grain patterns did not correlate with density. Overall, the flexural modulus of the quarter-sawn specimens was the highest in each species, and differed for the flat- and rift-sawn specimens depending on the species. We attribute the difference in flexural modulus among different grain patterns in a given species to differences in the arrangement and orientation of wood cells, and the difference between soft- and hardwood to their anatomical differences [13].

The rift-sawn softwood boards had significantly lower MOE than other patterns (Fig. 4). For Chamaecyparis obtusa, the density of the rift-sawn specimens was slightly higher than those of the other specimens. However, the MOE of the rift-sawn specimens was 49% and 25% of that of the flat- and quarter-sawn specimens, respectively. For Cryptomeria japonica, the MOE of the rift-sawn specimens was only 19% and 13% of that of the flat- and quarter-sawn specimens, respectively. A lower MOE means that the material is easier to bend. Thus, in thin wood materials, such as the kokera board, the end-grain pattern determines the flexural performance.

Tracheid deformation

Figure 5 shows the rate of change of the T/R ratio and diagonal ratio of Chamaecyparis obtusa as functions of the flexural displacement. For flat- and quarter-sawn specimens that fractured at flexural displacements of approximately 3 mm, the rate of change is only presented for displacements of 0 and 2 mm. Because the end-grain orientations of the flat- and quarter-sawn specimens were orthogonal to each other, their rates of change were reversed.

Among the end-grain patterns tested, the quarter-sawn wood showed the highest rate of change of the T/R ratio in both the compression and tension parts of the specimen at a flexural displacement of 2 mm. The flexural failure of solid wood propagates inward from the initial crack in the tension part of the specimen. Therefore, the results presented in Fig. 5b show that approximately 10% of the rate of change of the T/R ratio of the tracheids causes the failure of specimens in all grain patterns.

The diagonal ratio was a better indicator than the T/R ratio to explain the tracheid deformation in the rift-sawn wood. The rate of change of the diagonal ratio of the tracheids in the rift-sawn specimens linearly increased or decreased, exceeding 20% at a flexural displacement of 15 mm. The linear increase or decrease in the rate of change means the tracheid gradually deformed without strong resistance against compression and tension stresses induced by the flexural load. In addition, we assume that the deformation is due to the deformation of the corner cell walls of the tracheid, rather than compression and tension on the radial and tangential walls.

The cell walls of the flat- and quarter-sawn specimens subjected to the compression and tension generated under the flexural load were slightly rounded (Fig. 6a and b). By contrast, in the rift-sawn specimen, only slight deformation of the cell wall was observed, even though the cells became increasingly deformed with increasing displacement (Fig. 6c). Deformation of the radial and tangential walls was observed only at a displacement of 15 mm, just before the specimen failure. For Cryptomeria japonica, the change in the shape of the tracheids under the flexural load was almost identical to that of the tracheids of Chamaecyparis obtusa as shown in Fig. 6.

Discussion

The flexural behavior of wood specimens differed between softwood and hardwood, and among end-grain types within a given softwood species. The higher dimensional stability and processability of softwood than hardwood species (due to their lower density, simpler cell composition, and more regular cell arrangement) are the two main reasons they were used as kokera boards [14]. This is also why quarter- and rift-sawn boards were chosen, whereas flat-sawn boards were excluded. Typical cross-sectional optical micrographs of four wood specimens are shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

In the quarter-sawn specimens at a flexural displacement of 2 mm, the rate of change of the shape deformation of the tracheid was high in both the compression and tension parts of the specimen (Fig. 5a and b). We attribute this phenomenon to the flexural deformation of the specimen already being in the plastic deformation regime. Moreover, because rate of change in the tension part of the flat-sawn specimen was high, we conclude that this specimen entered the plastic region at a flexural displacement of 2 mm (Fig. 5b). The slight increase in the rate of change of the T/R ratio at an 8-mm displacement in the tension part of the rift-sawn specimen can be explained by the transition from elastic to plastic deformation, which is consistent with the load–displacement curve of Chamaecyparis obtusa as shown in Fig. 3a. The higher rate of change of the quarter-sawn specimen is due to the large stiffness gradient between the earlywood and latewood. In the quarter-sawn specimens of Chamaecyparis obtusa and Cryptomeria japonica—owing to the rapid transition from earlywood to latewood, and the grain orientation, which is arranged almost parallel to the flexural load direction—the cell deformation is concentrated in earlywood cells with relatively low stiffness. By contrast, in flat- and rift-sawn specimens, earlywood and latewood are evenly subjected to the flexural load. In other words, the high rate of change of the tracheids in the quarter-sawn specimens results from the cell deformation concentrated in earlywood.

Cell deformation in cellular structures is greatly influenced by the direction of the force applied to the cells [13, 15]. Thus, the excellent flexibility of rift-sawn softwood boards can be attributed to off-axis loading. In the flat- and quarter-sawn boards, the tensile and compressive stresses generated in the tracheid walls by the flexural load are on-axis loadings applied parallel to the orientation of the radial and tangential walls. By contrast, there is an off-axis loading in the rift-sawn board, in which the orientation of the cell walls and the directions of the tensile and compressive loads are not parallel. In a previous study, finite element analysis revealed that the effective transverse modulus of solid wood was greatly reduced by off-axis loading [16]. Using the vertical expansion model for square and hexagonal cell structures, Mihai and Goriely [15] demonstrated that the tensile stress concentrated on the straight cell walls parallel to the load direction under on-axis loading, whereas under off-axis loading, the stress concentrated in the corner walls where the radial and tangential walls joined. In other words, compression or tension under off-axis loading is not concentrated on the radial or tangential walls, but is efficiently distributed to the corners, resulting in flexible deformation of the tracheid. Therefore, we consider that off-axis loading is a major contributor to the excellent flexibility of rift-sawn softwood boards. In contrast, hardwoods have a relatively small difference in flexural behavior by the angle of the end grain because of the structure in which circular wood fibers are hexagonally packed (see also Additional file 3: Fig. S3). Rather, anatomical elements, such as ray and vessel, are important factors that induce anisotropy of mechanical behavior due to end-grain orientation [17].

The cell walls of the softwood tracheid have a tapered shape that becomes thicker from the center toward both ends (Fig. 7c). Thicker cell wall corners can handle greater loads and deformations. A higher Young’s modulus can be expected in a tapered wall than in a cell wall with a uniform thickness owing to the increased stiffness around the cell corners [18]. We also consider this characteristic of the tracheid wall to contribute to the excellent flexibility of the rift-sawn softwood board. Mimorikawa and Fujita reconstructed the shape of earlywood tracheids in 22 species using Fourier transform image analysis [19]. In a hexagonal model, the reconstructed tracheids were different for each species in cell size, ratio of the radial wall length to the tangential wall length, the angle of the radial wall, and the cell arrangement. These parameters influence the physical and mechanical behaviors of softwoods [11, 20,21,22]. We believe that the cell morphology and aggregates also influence the flexural anisotropy of softwoods.

Illustrations of on-axis (a) and off-axis (b) loadings applied to a tracheid during the bending of wood, and the shape of the tracheid with tapered ends (c). The arrows and colored areas in (a) and (b) indicate the direction of compressive or tensile stress and cell wall portions where the load is concentrated during deformation, respectively

Conclusions

Inspired by the use of rift-sawn softwood boards to cover curved surfaces in Kokerabuki, we investigated the flexural anisotropy of softwoods imparted by end-grain orientation. The off-axis loading induced by the orientation of the tracheids and their aggregates leads to the excellent flexibility of the rift-sawn softwood boards. We also conclude that the tapered shape of the tracheid walls contributes to the flexibility of softwoods. Our conclusions are supported by a body of studies on the shape and orientation of cells in cellular solids, including wood. Future research on anisotropy of softwoods might extend to the explanations of various properties over a wider range of end-grain angles and applications of the unique flexural properties of rift-sawn softwood boards.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- MOE:

-

Modulus of elasticity

- MOR:

-

Modulus of rupture

- MC:

-

Moisture content

References

Yokoyama S (2016) Restoration discussion of Saitama Prefecture specified tangible cultural property Yakyu Inari shrine (in Japanese). AIJ J Technol Des 22(52):1143–1148

Ross RJ (ed) (2010) Wood handbook: wood as an engineering material. General Technical Report FPL-GTR-190. USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison

Hu Y, Nakao T, Nakai T, Gu J, Wang F (2005) Effects of grain angles of face veneer on surface wave velocities and dynamic shear moduli of wood-based composites. J Wood Sci 51:286–289

Follrich J, Teischinger A, Gindl W, Müller U (2007) Effect of grain angle on shear strength of glued end grain to flat grain joints of defect-free softwood timber. Wood Sci Technol 41(6):501–509

Tanaka S, Fujiwara Y, Fujii Y, Okumura S, Togo H, Kukutsu N, Nagatsuma T (2011) Effect of grain direction on transmittance of 100-GHz millimeter wave for hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa). J Wood Sci 57:189–194

Kawahara K, Ando K, Taniguchi Y (2015) Time dependence of Poisson’s effect in wood IV: influence of grain angle. J Wood Sci 61:372–383

Matsuda Y, Fujiwara Y, Fujii Y (2019) Effect of grain angle on the strain distribution during orthogonal cutting of hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa) measured using a digital image correlation method. J Wood Sci 65:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-019-1824-2

Liu Z, Zhang Z, Ritchie RO (2020) Structural orientation and anisotropy in biological materials: functional designs and mechanics. Adv Func Mater 30(10):1908121. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201908121

Kabir MF, Daud WM, Khalid K, Sidek HAA (1998) Dielectric and ultrasonic properties of rubber wood. Effect of moisture content grain direction and frequency. Holz als Roh-und Werkstoff 56(4):223–227

Brémaud I, Gril J, Thibaut B (2011) Anisotropy of wood vibrational properties: dependence on grain angle and review of literature data. Wood Sci Technol 45(4):735–754

Watanabe U, Fujita M, Norimoto M (1998) Transverse shrinkage of coniferous wood cells examined using replica method and power spectrum analysis. Holzforschung 52(2):200–206

Ishimaru Y, Iida I (2001) Transverse swelling behavior of hinoki (Chamaecyparis obtusa) revealed by the replica method. J Wood Sci 47(3):178–184

Gibson LJ, Ashby MF (1999) Cellular solids: structure and properties. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stamm AJ (1952) Surface properties of cellulosic materials. Wood Chem 2:691–814

Mihai LA, Goriely A (2014) Nonlinear Poisson effects in soft honeycombs. Proc R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci 470(2169):20140363. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2014.0363

Nairn JA (2007) A numerical study of the transverse modulus of wood as a function of grain orientation and properties. Holzforschung 61(4):406–413

Miyoshi Y, Kojiro K, Furuta Y (2018) Effects of density and anatomical feature on mechanical properties of various wood species in lateral tension. J Wood Sci 64(5):509–514

Watanabe U, Norimoto M, Morooka T (2000) Cell wall thickness and tangential Young’s modulus in coniferous early wood. J Wood Sci 46(2):109–114

Midorikawa Y, Fujita M (2005) Transverse shape analysis of xylem ground tissues by the Fourier transform image analysis, 3: Shape reconstruction of earlywood tracheids in 22 species and some parameters for normalizing cell shapes (in Japanese). J Japan Wood Res Soc 51(4):218–226

Watanabe U, Norimoto M, Ohgama T, Fujita M (1999) Tangential Young’s modulus of coniferous early wood investigated using cell models. Holzforschung 53(2):209–214

Watanabe U, Fujita M, Norimoto M (2002) Transverse Young’s moduli and cell shapes in coniferous early wood. Holzforschung 56(1):1–6

Karakoç A (2016) Shape and cell wall slenderness effects on the stiffness of wood cell aggregates in the transverse plane. Maderas Ciencia y tecnología 18(4):689–700

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Mr. Satoshi Yoshida and Mr. Hironori Takeshita, Cultural Properties Division, Kyoto Prefectural Board of Education, for providing useful information during the initial stage of this study. The image shown in Fig. 1 was reproduced under the permission from Kyoto Prefectural Board of Education. They also thank Adam Brotchie, PhD, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Number H1805485) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH was a major contributor in performing the experiments and in writing the manuscript. HI, TN, and JS reviewed the data theoretically. JS designed and supervised the work. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Cross-sectional micrographs of Chamaecyparis obtusa, Cryptomeria japonica, Populus suaveolensis, and Cerasus serrulata.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2.

Real-time three-point flexural test of Cryptomeria japonica in three end-grain orientations.

Additional file 3: Fig. S3.

Replica images of wood fibers in flat-, quarter-, and rift-sawn specimens of Populus suaveolensis with various flexural displacements.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, SW., Isoda, H., Nakagawa, T. et al. Flexural anisotropy of rift-sawn softwood boards induced by the end-grain orientation. J Wood Sci 67, 14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-021-01946-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-021-01946-y