Abstract

Double-suction centrifugal pumps have been applied extensively in many areas, and the significance of pressure fluctuations inside these pumps with large power is becoming increasingly important. In this study, a double-suction centrifugal pump with a high-demand for vibration and noise was redesigned by increasing the flow uniformity at the impeller discharge, implemented by combinations of more than two parameters. First, increasing the number of the impeller blades was intended to enhance the bounding effect that the blades imposed on the fluid. Subsequently, increasing the radial gap between the impeller and volute was applied to reduce the rotor-stator interaction. Finally, the staggered arrangement was optimized to weaken the efficacy of the interference superposition. Based on numerical simulation, the steady and unsteady characteristics of the pump models were calculated. From the fluctuation analysis in the frequency domain, the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude at the blade passing frequency and its harmonics, located on the monitoring points in the redesigned pumps (both with larger radial gap), are reduced a lot. Further, in the volute of the model with new impellers staggered at 12°, the average value for the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude decreases to 6% of that in prototype pump. The dimensionless root-mean-square pressure contour on the mid-span of the impeller tends to be more uniform in the redesigned models (both with larger radial gap); similarly, the pressure contour on the mid-section of the volute presents good uniformity in these models, which in turn demonstrating a reduction in the pressure fluctuation intensity. The results reveal the mechanism of pressure fluctuation reduction in a double-suction centrifugal pump, and the results of this study could provide a reference for pressure fluctuation reduction and vibration performance reinforcement of double-suction centrifugal pumps and other pumps.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Double-suction centrifugal pumps have been employed in a variety of applications, such as oil pipeline, drainage, irrigation and other hydraulic transportation projects. In these situations, their relatively high flow capacity and more balanced axial force have been utilized. As a particular type of vane pump, the double-suction centrifugal pump exhibits flow rates twice that of a single-suction centrifugal pump with the same impeller diameter. Additionally, because the two back-to-back impellers are arranged symmetrically across the shaft, the axial force in the double-suction centrifugal pump is well balanced [1]. In the present study, the double-suction centrifugal pump investigated is used in crude oil pipeline transport projects, which has a high-demand for vibration and noise.

In fact, the rotor-stator interaction between the rotating impeller and the stationary volute tongue is the root cause of the unsteady flow in centrifugal pumps. The unsteady flow phenomena, including secondary flow, flow separation, and jet-wake flow, excites the pressure fluctuations, mechanical vibration and air-borne noise [2,3,4,5,6,7]. In terms of pressure fluctuations in conjunction with the pump noise, many researchers have performed numerous experiments and simulations. For example, Spence et al. [8] demonstrated that the numerical simulations could accurately predict the flow fluctuation features at most pump locations, and subsequently concluded that the cutwater gap and vane arrangement exerted the most significant effect on pressure pulsations in a centrifugal pump [9]. Barrio et al. [10] studied the effect of various outlet diameters on the fluid-dynamic pulsations in pumps. As expected, the intensity of the pressure fluctuation reduced as the blade-tongue gap increased. Yang et al. [11, 12] performed experimental, numeral, and theoretical research on impeller diameter influencing centrifugal pump-as-turbine, and then studied the effect of different numbers of blades on the fluid-dynamic pulsations in pumps, concluding that the amplitude of the pressure fluctuations reduced with the increasing blade number. Wang et al. [13] compared single- and double-suction centrifugal pumps regarding hydraulic performance; this would provide guidance for the design of excellent hydraulic models and multistage double-suction centrifugal pumps. Pavesi et al. [14] highlighted that fluid-dynamical unsteadiness produced asymmetrical rotating pressure at the impeller outlet in an experimental research on flow field instability of a centrifugal pump. Zhao et al. [15] analyzed the effect of rotating stall on the unsteady flow, and pressure fluctuations at part load operation. This work indicated that the rotating stall frequency was lower than the rotating frequency, and there was a relationship between the rotating stall and the rotor–stator interaction. Stel et al. [16] explored the fluid flow in the first stage of a two-stage centrifugal pump with a vane diffuser and revealed the different flow behaviors of the pump at different flow rates and rotor speeds. Yao et al. [17] investigated an adaptive optimal-kernel time-frequency representation based on fast Fourier transform (FFT) and revealed the trends of pressure fluctuations in a double-suction centrifugal pump.

According to Jorge et al. [18], there exists some degree of modulation, which is the result of the combination of the perturbations induced when the blades pass by the volute tongue and, on the other hand, the hydraulic disturbances induced by the local pressure variations near the vicinity of the impeller exit and the volute tongue. The former has a significant effect on a large part of the pump, whereas the latter only affect some local areas. These results are in agreement with that reported in Ref. [19,20,21]. As we all know, the radial gap between impeller outlet and volute tongue exerts a great influence on the pressure fluctuation and hydraulic characteristics of the centrifugal pump. For a given flow rate, the pressure fluctuation amplitude increases when reducing the blade-to-tongue gap [10, 22]. This can be explained in this way that the smaller the radial gap, the smaller rotor–stator distance, the less space left for the flow to adapt to the geometry changes, thus leading to larger pressure gradients and larger stresses [10]. As stated by Spence et al. [8], the percentage contribution of the blade-to-tongue gap to the pressure variation at a location near the volute tongue is even up to 67% at designed flow rate. However, this gap cannot be infinitely large since there is usually an optimal value for the pump to achieve its highest efficiency [23]. Another important factor is that there is always a space limitation when designing a pump, where the infinite radial gap is unrealistic in engineering application. Therefore, simply increasing the radial gap of the pump to reduce pressure fluctuation is far from enough.

From these previous investigations, conclusions can be drawn that several parameters such as cutwater gap, impeller outlet diameter, blades number, and vane arrangement have a significant effect on the pressure fluctuation of double-suction centrifugal pump. These papers make comparisons only with one single parameter, meanwhile a more effective method based on increasing the flow uniformity at the impeller discharge, which is implemented by combinations of more than two parameters, can be explored further to reduce the pressure fluctuation in a double-suction centrifugal pump.

In this study, a double-suction centrifugal pump with a high-demand for vibration and noise is investigated. First, splitter blades were added in the new impeller; larger radial gap between the impeller outlet and the volute tongue was applied; and two different staggering arrangements were introduced to be investigated by numerical simulation and experimental study. Further, the hydraulic performances of the prototype and the redesigned pumps were validated with the experimental data. Subsequently, the frequency domain of the pressure fluctuation recorded at monitoring points was obtained from unsteady simulations. These were analyzed in detail and the initial flow field was extracted to reveal the mechanism for the reduction in pressure fluctuations. Finally, a vibration experiment was conducted to verify the effects of the vibration and noise reduction. This is significant, as it provides a solid foundation for the reduction of pressure fluctuations, vibration, and noise performance in double-suction centrifugal pumps.

2 Pump Model and Numerical Simulation Method

The pump model mainly consists of two impellers, a double volute, and a double-suction chamber, which is shown in Figure 1. The fluids flow along the direction marked with the two arrows (shown in the left picture). The prototype impellers in Figure 1 (shown in the right picture) are in a straight arrangement, and the medial hub of the impellers terminates midway, with a round nose of radius 4 mm. The impellers are an important aspect of the design. Therefore, only the impellers are changed, while the double volute and the double-suction chamber remain the same in the redesign process. The pump operates at the design flow rate of 3800 m3/h, with a head of 170 m. Based on these design requirements, the impeller is redesigned in the following process described in Figure 2, and the detailed design parameters of the pumps are stated in Table 1 [24,25,26,27].

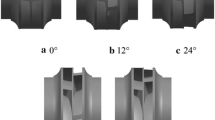

The impeller in prototype pump model #1 has six blades, whereas the redesigned pumps (models #2, #3, and #4) have seven primary blades and seven splitter blades. For processing convenience, the splitter blades are obtained from shifting the primary blades in the circumferential direction and cutting the leading edge. As mentioned previously, there is a round nose in the meridian surface of model #1, and it’s the same with model #2. Meanwhile, in models #3 and #4, the central hub is elongated to the outlet diameter of the impeller and the axial clearance between the two impellers is 8 mm. The impeller outlet diameters in the four models (#1, #2, #3, and #4) are 396, 396, 390, and 390 mm, respectively; therefore, the radial gaps between the impeller discharge and the volute tongue are 8, 8, 11, and 11 mm, respectively. In models #1 and #2 the impellers are in a straight arrangement, in model #3 the impellers are staggered with no angle, while in model #4 there is a 12° staggering angle in the two-side impellers [28].

The computational domain and the grid of the pump using the redesigned impeller is shown in Figure 3, which incorporates the double-suction chamber, impellers (models #4), double volute, and the extension tubes at the inlet and outlet locations. Hexahedral structured cells were applied to the inlet and outlet extension tubes using the mesh generation tool ICEM CFD, while the double-suction chamber, volute, and the impellers were meshed in the form of unstructured tetrahedral cells.

The simulation for three-dimensional incompressible flow inside the pump under both steady and unsteady processes was performed in the commercial CFD code ANSYS FLUENT 14.5. The Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations (RANS) were resolved by the Realizable k-ε model, as well as the standard wall functions. The SIMPLEC algorithm was chosen to match with the pressure-velocity coupling of the solver, while the second-order upwind scheme was used for the momentum, turbulence kinetic energy, and turbulence dissipation rate terms. In the calculation, the residual for continuity and momentum equations, turbulence kinetic energy (k) and dissipation rate (ε) was set to a magnitude below 10−5. The multiple reference frame approach (MRF, also called frozen rotor approach) was employed in the study, and the frame motion was exerted on the impeller to simulate the impeller’s rotating motion. The remaining components of pump model were set as the stationary zones, and the data transmission among different zones was implemented by interfaces between adjacent zones.

With regard to the steady calculation, the velocity inlet and the pressure outlet were considered separately as the boundaries of the inlet and the outlet. Additionally, the simulation results of the steady calculation were assumed as the original conditions of the unsteady calculation to obtain a satisfactory convergence. The sliding mesh scheme was conducted for the unsteady calculation [29]. The time step for the unsteady simulation was 5.5928×10−5 s, which was equivalent to 1° of impeller rotation.

The dimensionless pressure/head coefficient \(\psi\) and the flow coefficient \(\phi\) [30, 31] are respectively defined in Eq. (1) and Eq. (2):

where \(\Delta p_{tot}\) is the total pressure difference between the inlet and outlet, \({\text{Pa}}\); \(u_{{\text{a}}}\) is the outer circumferential velocity of the impeller, \({\text{m/s}}\); \(d_{{\text{a}}}\) is the outer diameter of the impeller, \({\text{m}}\).

For unsteady simulation, the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude \(p_{{\text{A}}}^{*}\) is defined in Eq. (3):

The results of mesh independent verification (including the steady and unsteady simulation verification) with model #4 at design flow rate are shown in Figure 4. The head coefficient and hydraulic efficiency were calculated from the steady numerical simulation, while the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude at blade passing frequency (BPF) on two given monitoring points (V1 and V4, see Section 4.1) were calculated from the unsteady numerical simulation. The discrepancy of the pressure coefficient between 5.63 million grids and 13.76 million grids is only 0.3%, and the discrepancy of the efficient is only 0.26%, which is small enough. Additionally, the variation of the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude is less than 5%. Therefore, the grid number is ensured to be larger than 5.63 million for the following steady and unsteady simulations. Moreover, the y+ near the boundary wall in the following calculations is ensured to be within a reasonable range of 30‒200.

3 Performance Experimental Verification

For each of these geometric models, the performance at different flow rates was obtained from steady CFD simulations, where the flow rates matched the design flow rate at percentages of 50, 60, 80, 100, 120, and 140. To verify the numerical simulation results, an experiment was conducted for comparison with the CFD values. The schematic diagram of the test bench for the pump was illustrated in Figure 5. The auxiliary pump was used to transport water from the underground water tank to the test pump and form a complete water circulation. The tested pump was driven by a variable frequency AC-motor, between which was a torque transducer to measure the rotating speed and shaft torque. The inlet and outlet pressure transducers were respectively placed in the inlet and outlet pipe to obtain the inlet and outlet pressure values. A magnetic flow meter was mounted in the discharge pipe to measure the flow rate, which was regulated through the regulating valve located on the outlet pipe. The parameters at design flow condition could be calculated from measured parameters through similar conversion, as shown in Eq. (4). The accuracy of each instrument and the errors for these calculated parameters were described in Table 2.

where \(P_{{\text{i}}} ,P_{{\text{o}}}\) are the inlet and outlet pressure, \({\text{MPa}}\); \(n_{{\text{e}}}\) is the measured rotating speed, r/min; \(H_{{\text{e}}} ,H\) are the head at \(n_{{\text{e}}} ,n\) rotating speed, \({\text{m}}\); \(Q_{{\text{e}}} ,Q\) are the flow rate at \(n_{{\text{e}}} ,n\) rotating speed, \({\text{m}}^{{3}} {\text{/h}}\); \(M_{e}\) are the torque at \(n_{{\text{e}}}\) rotating speed, \({\text{kW}}\); \(P_{{\text{e}}} ,P\) are the shaft power at \(n_{{\text{e}}} ,n\) rotating speed, \({\text{kW}}\); and \(\eta\) is the efficiency.

Figure 6 displays a comparison of the simulated results (0.5Qd-1.2Qd) with the experimental data for model #4. The head coefficient at design flow rate in model #4 is 0.145. Figure 6a shows the comparison in the head coefficient. The experimental data are larger than the CFD results, but all the differences are within 10%. The higher experimental head is probably attributable to minor fluctuations of the motor within the running process. Further, the deviation at small flow rates may be caused by the flow condition that tends to be worse, along with factors such as the secondary flow, vortex, and flow separation. Here, the CFD simulation cannot restore the real flow field completely. Figure 6b displays an efficiency comparison, and reasonable agreement is found with a discrepancy of less than 5%. In summary, the numerical simulation achieved a reasonable agreement with the experimental data, and the CFD results could be utilized for further investigations.

Figure 7 demonstrates the performance curves of different models obtained from steady CFD calculations (0.6Qd‒1.4Qd). As shown in Figure 7a, the head coefficient in the four models decreases as the flow rate increases. Additionally, due to the splitter blades increasing the work capability of the pump, the head coefficient in the redesigned pumps is higher than that in prototype pump across the flow range. Figure 7b compares the hydraulic efficiencies of the four models. In the four models, the efficiency increases first and then declines as the flow rate decreases. At design flow rate, the efficiencies of models #3 and #4 are slightly higher than that of the prototype pump, while in model #2 the efficiency is the lowest. This can be explained in Section 4.3.

The following contents in this paper always refer to the results at design flow rate.

4 Results and Analysis on Pressure Fluctuation

4.1 Locations of Monitoring Points

A series of pressure monitoring points, as depicted in Figure 8, were distributed at different positions across the impeller and the volute to obtain the pressure fluctuation of the internal flow field. Points P1–P8, with an adjacent interval angle of 45° in the circumferential direction, were selected from the middle plane of the impeller. In the radial direction, these points were located in a circle with a diameter 4 mm larger than the impeller outlet diameter; among these, points P1 and P5 were arranged near the tongue. In the volute, points V1–V8 were positioned in a circle of 410 mm in diameter at the center plane, and the circumferential angular difference between the two adjacent points was 45°. Further, points V1 and V5 were located near the tongue. Additionally, the diameter of the interface between the rotating and stationary reference frames was 404 mm.

For unsteady numerical simulations, 10 revolutions of the impeller (10T = 0.20134 s, T is the rotating period), was regarded as the total calculation time, which was sufficient for the unsteady calculation to reach a relatively stable condition. For the convenience of comparisons, only four points for each model (P1, P3, P5, and P7 in the impeller, V1, V3, V5, and V7 in the volute), are listed herein, as the remaining points presented similar trends.

4.2 Pressure Fluctuation Results

Figure 9 demonstrates the frequency and time domains of the pressure fluctuation on the monitoring points in the impeller for the four models. For the accuracy and reliability of the unsteady simulation, the results of the last four rotations of the 10 revolutions in the unsteady simulation were extracted to perform spectral analysis.

The dimensionless pressure \(p^{*}\)™ is defined in Eq. (5):

where \(p\) is the static pressure, \({\text{Pa}}\).

As shown in Figure 9, the dominant frequencies in the impeller of model #1 are the primary BPF (298 Hz, which is six times the rotating frequency of the shaft, 6fn) and its harmonics. However, in models #2, #3 and #4, the predominant frequencies in the spectrum are the primary BPF (347.7 Hz, 7fn) and its harmonics. From the time domain, it is apparent to recognize that, during each impeller rotation, there are 6 peaks and troughs in model #1, and 14 peaks and troughs in models #2, #3 and #4. Further, it is noteworthy that the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude at dominant frequencies and the range of the pressure fluctuation at time domain in models #3 and #4 are lower than that in model #1 and #2. Additionally, as the impeller rotates, the pressure between points P1 and P5, and between points P3 and P7 exhibits the similar variation tendency. This is related to their positions, where points P1 and P5 are near the volute tongues, while points P3 and P7 are in the middle of the two volute tongues.

Figure 10 presents the frequency and time domains of the pressure fluctuation on the monitoring points in the volute for the four models. Similarly, the dominant frequencies of the pressure on the monitoring points in the volute contained 6fn and its harmonics in model #1, and 7fn and its harmonics in models #2, #3 and #4. At the time domain, there are also 6 peaks and troughs in model #1, and 14 peaks and troughs in models #2, #3 and #4. It can be seen that the dimensionless pressure fluctuation amplitude at dominant frequencies and the range of the pressure fluctuation at time domain in models #3 and #4 are lower than that in models #1 and #2. Additionally, a similar variation tendency of the pressure amplitude curves between points V1 and V5, and between points V3 and V7 was found in the volute, but the magnitude was lower than that in the impeller; thus, the level of pressure fluctuation in the volute is reduced.

4.3 Mechanism of Pressure Fluctuation Reduction

The root-mean-square (RMS) value [22] of pressure is introduced to indicate the pressure fluctuation intensity in the flow field. It is defined by

where \(N\) is the number of time steps in one impeller revolution, \(i\) means the ith time step, and \(p(x,y,z,t_{i} )\) is the static pressure in location \((x,y,z)\) at the ith time step.

For the convenience of comparison, the RMS pressure is weighted by \(0.5 \cdot \rho \cdot u_{{\text{a}}}^{{2}}\) as shown in the Eq. (7):

As the BPF is crucial in the frequency spectrum, the pressure fluctuation amplitudes at 1 and 2 times the primary BPF are added to obtain the pressure fluctuation characteristics associated with the BPF [32]. Figure 11 compares the characteristics of the average pressure fluctuation amplitude on monitoring points P1–P8 in the impeller and monitoring points V1–V8 in the volute for all four models. In model #1, the black column represents the average amplitude at the frequency of 6fn, the red column represents that at the frequency of 12fn, while in models #2, #3 and #4, the black column represents the average amplitude at the frequency of 7fn, the red column represents that at the frequency of 14fn.

It is clear that the amplitudes at the frequency of 14fn in model #2 are extremely high both in the impeller and volute. However, the amplitudes of models #3 and #4 are reduced significantly in the impeller and volute. In the volute of model #4, the average value is only 6.4% of that in model #1. This effect is attributed to the pressure contour on the middle surface of the impeller in model #2 that became worse at TE tip, and in models #3 and #4 that became relatively uniform, as shown in Figure 12. In model #2, the RMS pressure was generally at high level across the flow channel of the impeller, which presented strong fluctuation property. Additionally, the wake-jet structure identified at TE tip excited the fluctuation in the pressure field at the impeller outlet; thus acted as the source of the fluctuation and created frequencies corresponding to the BPF. In model #1, the zone at the first 20% of the blade was occupied by a large low-pressure zone (marked with a circle in Figure 12), and there was a pressure non-uniformity zone at the pressure surface near the rear part of the blade (marked with a square in Figure 12). However, in models #3 and #4, a well-distributed pressure in the whole blade channel improved flow uniformity, and reduced the level of pressure fluctuations; therefore, the pressure fluctuation was reduced. As shown in Figure 12, the dimensionless RMS pressure contour was at relatively high level in the redesigned impellers with splitter blades, especially in model #2, which was the reason for the increased head in Figure 7a. Meanwhile, the non-uniform pressure distribution along the impeller outlet in model #2 was one of the causes of the lower efficiency in Figure 7b.

In the impeller, the magnitude in models #3 and #4 is almost the same, as shown in Figure 11a. However, in the volute, Figure 11b shows that the magnitude in model #4 is lower than in model #3. First, in models #3 and #4, each impeller is exactly the same; therefore, the pressure contours in the impellers almost exhibit no difference, as shown in Figure 12. Hence, the pressure fluctuation amplitudes in the impellers of models #3 and #4 are almost equal. Next, seven primary blades, and seven splitter blades were in the redesigned impeller; when the impeller rotates, these blades interact with the stationary volute tongue. Nevertheless, in model #3, the impellers are arranged straight, therefore the blades of the two sides interact with the volute simultaneously, thereby enhancing the efficacy of the interference superposition [33]. The impellers in model #4 are in a staggered arrangement with a 12° angle, where the blade of one side is located nearly on the middle of the two blades of the other side, thus avoiding the superposition. This can explain the lower amplitude in model #4 compared with model #3 in the volute.

As can be seen in Figure 12, the pressure contour of the blade passage between two adjacent blades in model #1 was smooth near the blades, but in the middle area, the contour line became twisted and deformed. This phenomenon was worsened as approaching the impeller discharge; therefore, the flow uniformity along the flow path was unsatisfactory, resulting in the serious pressure fluctuation of the pump. After adding splitter blades in model #2, the fluid was well bounded by the increased blades, which was similar with the effect of infinite blade number on improving the flow field; hence, the pressure distribution in each blade passage became more uniform. Likewise, the multi-blade effect on flow uniformity existed in models #3 and #4. But unfortunately, the influence of the limited radial gap between impeller outlet and volute tongue in model #2, namely the wake-jet structure at the TE tip, prevailed against the multi-blade influence, increasing the bounding effect that the blades imposed on the fluid; thereby a less unsatisfactory result was obtained in model #2.

For a clear comparison, the dimensionless RMS pressure at a circle of 4 mm far from the impeller outlet diameter in the impeller and a circle with a diameter of 410 mm in the volute for the four models was depicted in Figure 13. As shown in Figure 13a, there was a pressure fluctuation during the following angular displacement after passing each blade; what came with it was a local maximum and minimum, which was the source of the BPF and its harmonics in frequency domain. In models #1 and #2, the RMS pressure varied in a large scope, and the larger difference between the maximum and minimum represented the intense pressure fluctuation and the less uniform pressure distribution. Nevertheless, in models #3 and #4, the dimensionless RMS pressure kept a stable level with minor pressure distribution, leading to a more uniform flow distribution at the impeller outlet. This was consistent with the results in Figures 11, 12, and could explain the dominant frequency characteristics in Figure 9. Figure 13b shows that the magnitude of the dimensionless RMS pressure in the volute is lower than that in the impeller and the obvious peaks almost disappear. As the unsteady flow field at the impeller outlet is approaching the volute, it induces complex fields in the volute, which in turn, interacts with that in the impeller. If the flow at the impeller outlet is steady and uniform, the interaction between the impeller and the volute would be decreased, and the pressure fluctuations and excitation forces would be reduced greatly. The pressure at the impeller outlet in models #3 and #4 is in a relatively stable level than that in models #1 and #2, thus a reduced pressure fluctuation and a uniform pressure distribution along the volute are plotted in models #3 and #4.

Figure 14 shows the dimensionless RMS pressure on the middle surface of the volute for the four models. It is clear that the RMS distribution is characterized by a pattern with a local maximum and minimum [20]. As the RMS distribution is independent of the relative positions of the impeller and volute, the blade profile is added to reveal the distance of the adjacent blades. In model #1, this modulation effect is intensive and the circumferential distribution of the RMS between the impeller discharge and volute tongue is uneven. As illustrated in Figure 14a, the pressure waves travel through the volute channel until meeting the wall, and a large zone influenced by this interaction turns up in the travelling path (marked with squares). After adding the splitter blades, the area of the influenced zones is narrowed in model #2 (marked with circles). However, because of the increasing blade number, the modulation effect is more intensive and the highly uneven pressure variation districts exist near every blade. This can explain why the RMS pressure curve in Figure 13b is fluctuating and why the local peak values appear periodically. Owing to the new impeller with larger radial gap between the impeller discharge and the volute tongue, the difference between the local maximum and minimum in model #3 is lower and the pressure distribution along the impeller outlet tends to be well distributed. In model #4, the staggered impellers relieved the interaction effect [34, 35], the intensive modulated zone nearly disappeared, and the flow became more uniform in the flow field.

4.4 Vibration Experimental Results

To verify the unsteady characteristics of the pump, vibration experiments for models #1 and #4 were conducted at the design flow rate of 3800 m3/h and a rotating speed of 2980 r/min. Vibration acceleration sensors were placed at different positions, thus the real-time signal could be obtained to extract the frequency spectrum through FFT. The vibration experiment was first performed with model #1 and the sampling rate was set to 40960 Hz. However, the low frequencies were of concern in this vibration experiment and according to the sampling theorem [36], a sampling rate of 20480 Hz was sufficient to capture the valid information regarding pump vibrations. Therefore, in the vibration experiment with model #4, 20480 Hz was chosen as the sampling rate, which would not affect the FFT.

The vibration monitoring point “outlet” was intended to measure the vibration acceleration in the horizontal direction at the outlet of the volute, which is marked in two circles in Figure 15. The FFT results were selected in Figure 16 to show the unsteady pressure fluctuation features. The vertical axis in Figure 16 is the vibration acceleration level with a reference acceleration of 1×10−6 m/s2.

As mentioned above, the original pump was denoted as model #1, and the best pressure fluctuation performance was found in model #4. Hence, these two pump models were experimented to make comparisons of the vibration characteristic. As shown in Figure 16, it’s obvious that a peak appears at BPF (299.2 Hz) in the spectrum of model #1; in model #4, the peak value at BPF (349.1 Hz) is not so clear. Owing to the minor fluctuation of the rotational speed, the experimental BPF (299.2 Hz and 349.1 Hz) are slightly away from the numerical results (298 Hz and 347.7 Hz). Additionally, the overall amplitude in model #4 is lower and the distribution of the vibration acceleration level across the whole frequency range is more uniform. Therefore, the reduced amplitude and well-distributed frequency spectrum of model #4 could qualitatively demonstrate the reduction effects of pressure fluctuation in model #4, as well as the vibration and noise.

5 Conclusions

-

1.

In this study, new impellers were designed to improve the performance of the prototype pump, and unsteady numerical simulations on the pressure fluctuation were performed. Further, the hydraulic and vibration experiments were conducted to confirm the characteristics of these pumps.

-

2.

The hydraulic performance of the redesigned impeller with multi-blades in model #4 achieved reasonable agreement with the experiment both in the head coefficient and efficiency. The head coefficient in the redesigned pumps is higher than that in prototype pump across the whole flow range; at design flow rate, the efficiencies of models #3 and #4 are slightly higher than that in model #1, and the efficiency in model #2 is the lowest. The pressure change and flow uniformity inside the pumps could be evaluated quantitatively and accurately through the pressure fluctuation analysis in the time and frequency domains. The pressure distribution tended to be more uniform and the pressure fluctuation was improved well when the impeller of each side had a staggered angle of 12°. The vibration experiment further reflected the effects of the vibration and noise reduction for the prototype pump.

-

3.

The design approach of increasing the flow uniformity at the impeller outlet, such as combination of multi-blades, larger radial gap and staggering arrangements, facilitated a reduction in pressure fluctuations inside the double-suction centrifugal pump, and could be applicable to other multi-blade fluid machinery.

References

W Dong, C L Wu. Analysis of flow characteristics and disc friction loss in balance cavity of centrifugal pump impeller. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 2016, 47(4): 29–35. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2016.04.005. (in Chinese).

S Melzer, A Pesch, S Schepeler, et al. Three-dimensional simulation of highly unsteady and isothermal flow in centrifugal pumps for the local loss analysis including a wall function for entropy eroduction. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2020, 142(11): 111209. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4047967.

A Posa, A Lippolis, E Balaras. Investigation of separation phenomena in a radial pump at reduced flow rate by large-eddy simulation. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2016, 138(12): 121101. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4033843.

H S Shim, K Y Kim. Relationship between flow instability and performance of a centrifugal pump with a volute. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2020, 142(11): 111208. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4047805.

Z Y Yang, Z R Liu, Y G Cheng, et al. Differences of flow patterns and pressure pulsations in four prototype pump-turbines during runaway transient processes. Energies, 2020, 13(20): 5269. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4033843.

X J Li, Z C Zhu, Y Li, et al. Investigation of pressure pulsations and flow instabilities in a centrifugal pump at part-load conditions. International Journal of Fluid Machinery & Systems, 2017, 10(4): 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957650916663326.

X J Li, Z C Zhu, Y Li, et al. Experimental and numerical investigations of head-flow curve instability of a single-stage centrifugal pump with volute casing. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 2016, 230(7): 633–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957650916663326.

R Spence, J Amaral-Teixeira. Investigation into pressure pulsations in a centrifugal pump using numerical methods supported by industrial tests. Computers & Fluids, 2008, 37(6): 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2007.10.001.

R Spence, J Amaral-Teixeira. A CFD parametric study of geometrical variations on the pressure pulsations and performance characteristics of a centrifugal pump. Computers & Fluids, 2009, 38(6):1243–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2008.11.013.

R Barrio, E Blanco, J Parrondo, et al. The effect of impeller cutback on the fluid-dynamic pulsations and load at the blade-passing. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2008, 103(11): 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2969273.

S S Yang, H L Liu, F Y Kong, et al. Experimental, numerical, and theoretical research on impeller diameter influencing centrifugal pump-as-turbine. Journal of Energy Engineering, 2013, 139(4): 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EY.1943-7897.0000128.

S S Yang, F Y Kong, X Y Qu, et al. Influence of blade number on the performance and pressure pulsations in a pump used as a turbine. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2012, 134(12): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4007810.

C Y Wang, F J Wang, Z C Zou. Comparative study on hydraulic performance of single-suction centrifugal pump and double-suction centrifugal pump. ASME 2017 Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting, Waikoloa, Hawaii, USA, July 30–August 3, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1115/FEDSM2017-69142.

G Pavesi, G Cavazzini, G Ardizzon. Time–frequency characterization of the unsteady phenomena in a centrifugal pump. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 2008, 29(5): 1527–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2008.06.008.

X R Zhao, Y X Xiao, Z W Wang, et al. Unsteady flow and pressure pulsation characteristics analysis of rotating stall in centrifugal pumps under off-design conditions. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2018, 140(2): 021105. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4037973.

H Stel, G D L Amaral, C O R Negrao, et al. Numerical analysis of the fluid flow in the first stage of a two-stage centrifugal pump with a vaned diffuser. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2013, 135(7): 071104. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4023956.

Z F Yao, F J Wang, L X Qu, et al. Experimental investigation of time-frequency characteristics of pressure fluctuations in a double-suction centrifugal pump. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2011, 133(10): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4004959.

P G Jorge, G P Jose, F F Joaaquı´n. The effect of the operating point on the pressure fluctuations at the blade passage frequency in the volute of a centrifugal pump. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2002, 124(3): 784–790. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1493814.

P Yan., N Chu, D Z Wu, et al. Computational fluid dynamics-based pump redesign to improve efficiency and decrease unsteady radial forces. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2016, 139(1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4034365.

R Barrio, J Fernández, E Blanco, et al. Estimation of radial load in centrifugal pumps using computational fluid dynamics. European Journal of Mechanics- B/Fluids, 2011, 30(3): 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechflu.2011.01.002.

Y Tao, S Q Yuan, J R Liu, et al. Influence of cross-sectional flow area of annular volute casing on transient characteristics of ceramic centrifugal pump. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2019, 32(4): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-019-0319-9.

G T Zeng, Q Q Li, P Wu, et al. Investigation of the impact of splitter blades on a low specific speed pump for fluid-induced vibration. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, 2020, 34(7): 2883–2893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-020-0620-7.

S S Yang, H L Liu, F Y Kong, et al. Effects of the radial gap between impeller tips and volute tongue influencing the performance and pressure pulsations of pump as turbine. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2014, 136(5): 054501. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4026544.

J Pei, W J Wang, S Q Yuan. Multi-point optimization on meridional shape of a centrifugal pump impeller for performance improvement. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, 2016, 29(11): 4949–4960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-016-1015-7.

Y M Lu, X F Wang, W Wang, et al. Application of the modified inverse design method in the optimization of the runner blade of a mixed-flow pump. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2018, 31: 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-018-0302-x.

B Qian, P Wu, B Huang, et al. Optimization of a centrifugal impeller on blade thickness distribution to reduce hydro-induced vibration. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2020, 142(2): 021202. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4044965.

B Qian, J P Chen, P Wu, et al. Study on the influence of centrifugal pump inlet flow field instability and methods of adjustment. Proceedings of the ASME-JSME-KSME 2019 8th Joint Fluids Engineering Conference. Volume 3B: Fluid Applications and Systems, San Francisco, California, USA, July 28–August 1, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1115/AJKFluids2019-4687.

D C Fu, F J Wang, P J Zhou, et al. Impact of impeller stagger angles on pressure fluctuation for a double-suction centrifugal pump. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2018, 31: 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-018-0203-z.

C Y Wang, F J Wang. Shape and position of sliding interface for transient flow simulation of centrifugal pump. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 2017, 49(1): 81–88. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2017.01.011. (in Chinese).

Q Q Li, G S Zhao, C S Wu, et al. Investigation on the energy exchange characteristics of the regenerative flow pump in an automobile fuel system. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2020, 142(11): 111206. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4047803.

Y F Wang, F Zhang, S Q Yuan, et al. Effect of URANS and hybrid RANS-large eddy simulation turbulence models on unsteady turbulent flows inside a side channel pump. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2020, 142(6): 061503. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4045995.

C L Xie, F P Tang, R T Zhang, et al. Numerical calculation of axial-flow pump's pressure fluctuation and model test analysis. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 2018, 10(4): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814018769775.

Y Song, H G Fan, W Zhang, et al. Flow characteristics in volute of a double-suction centrifugal pump with different impeller arrangements. Energies, 2019, 12(4): 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12040669.

F M Zhou, X F Wang. Effects of staggered blades on the hydraulic characteristics of a 1400-MW canned nuclear coolant pump. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 2016, 8(8): 4949–4960. https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814016657944.

Y S Zeng, Z F Yao, F J Wang, et al. Experimental investigation on pressure fluctuation reduction in a double suction centrifugal pump: influence of impeller stagger and blade geometry. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 2020, 142(4): 041202. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4045208.

F Badrieh. Sampling and the sampling theorem. in: Spectral, convolution and numerical techniques in circuit theory. Cham: Springer, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71437-0_25.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thanks to Ningbo Rocket Automobile Rocket Parts Co., Ltd for their critical support in the experiment test.

Funding

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52076186, 51839010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL and PW were in charge of the design optimization; BH and DW assisted with the experiments and the results analyses; QL performed the performance and vibration experiments of the pump models, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ Information

Qianqian Li, born in 1994, is currently a PhD candidate at College of Energy Engineering, Zhejiang University, China. She received her bachelor degree from China University of Petroleum, China, in 2016. Her research interests include design and optimization of centrifugal pumps and regenerative pumps.

Shiyang Li, born in 1990, is currently an engineer at Zhejiang Zhixin Technology Co., Ltd., China. He received his PhD degree on pumps and valves from Zhejiang University, China, in 2018.

Peng Wu, born in 1986, is currently an associate researcher at College of Energy Engineering, Zhejiang University, China.

Bin Huang, born in 1985, is currently an associate professor at Ocean College, Zhejiang University, China.

Dazhuan Wu, born in 1977, is currently a professor at College of Energy Engineering, Zhejiang University, China.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Li, S., Wu, P. et al. Investigation on Reduction of Pressure Fluctuation for a Double-Suction Centrifugal Pump. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 34, 12 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-020-00505-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-020-00505-8