Abstract

Comparison of the recently sequenced genome of the leprosy-causing pathogen Mycobacterium leprae with other mycobacterial genomes reveals a drastic gene reduction and decay in M. leprae affecting many metabolic areas, exemplified by the retention of a minimal set of genes required for cell-wall biosynthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mycobacterium leprae, 'Hansen's Bacillus', was the first human pathogenic bacterium to be identified, predating the discovery of the tubercle bacillus (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) by a decade. The genomes of both have now been decoded [1,2,3,4]. The genomes of other mycobacteria are also being sequenced, including those that cause opportunistic infections in people with AIDS (Mycobacterium avium) [5], bovine tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis) [6], and Johne's disease of cattle (Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis) [7]. The sequencing of Mycobacterium smegmatis [5], the laboratory model strain used for studying mycobacterial physiology and genetics, and of the phylogenetically related Corynebacterium glutamicum [5] and Corynebacterium diphtheriae [8], are also under way. Although clinical aspects of the virulent mycobacterial strains vary, they are all intracellular pathogens that are transmitted by the respiratory route and occupy macrophages as their preferred niche [9]. A number of antibodies crossreact amongst these bacterial species, indicating similarities in protein composition, and the basic cell-wall architecture is the same [10]. Thus, comparative genomics is a useful tool for identifying common and divergent pathways.

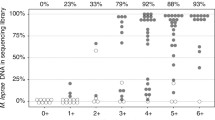

Cole et al. [1,3] have found that, compared to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome of 4,411,529 base-pairs (bp), which can potentially encode 3,924 genes [3], the M. leprae genome of 3,268,203 bp encodes only 1,604 proteins and contains 1,116 pseudogenes [1]. They have annotated and classified all these genes into various functional categories. Figure 1 depicts this drastic gene reduction and decay in M. leprae compared to M. tuberculosis, which affects nearly every aspect of metabolism.

The extent of gene reduction and decay in the genome of M. leprae. (a) The percentage of the total potential open reading frames assigned to major cellular functions are shown. (b) Each category has been sub-classified and the number of putative functional genes in M. leprae (after eliminating the pseudogenes) for each subclass are indicated by bold numbers, followed by the corresponding number in M. tuberculosis. The data were obtained from the databases of the M. leprae and M. tuberculosis genome projects [2,4] as annotated by Cole et al. [1,3].

Despite numerous experiments that demonstrated metabolic activity by labeling macromolecules such as phenolic glycolipid (PGL)-I, proteins, nucleic acids and lipids with radioactive precursors in bacteriological media or in macrophages infected with host-derived M. leprae, multiplication of M. leprae cells has not been achieved. The only sources of M. leprae are tissues from infected humans, armadillos or mouse footpads [11]. The failure to grow M. leprae cells in vitro may result from the combined effects of gene reduction and mutations in several metabolic areas (Figure 1b). Mutations are found in genes involved in regulation (encoding repressers, activators, two-component systems, serine-threonine kinases and phosphatases), detoxification (genes encoding peroxidases), DNA repair (the mutT, dnaQ, alkA, dinX, and dinP genes) and transport or efflux of metabolites such as amino acids (arginine, ornithine, D-alanine, D-serine and glycine), peptides, cations (magnesium, nickel, mercury, ammonium, ferrous and ferric ions and potassium), and anions (arsenate, sulfate and phosphate). In general, pseudogenes are found more frequently in degradative, rather than synthetic, pathways. Genes for the synthesis of most small molecules, such as amino acids, purines, pyrimidines and fatty acids, and for the synthesis of macro-molecules such as ribosomes, aminoacyl tRNAs, RNA and proteins, are reasonably intact.

In terms of gene reduction, there are fewer genes in almost every category, but notably affected are insertion sequences (IS) and the acidic, glycine-rich families of proteins that have proline-glutamic acid (PE) or proline-proline-glutamic acid (PPE) motifs at the amino terminus; these proteins may confer antigenic variation. Repressors, activators, oxidoreductases and oxygenases are also affected. Thus, while preserving genes required for its transmission, establishment and survival in the host, M. leprae has discarded genes that can be compensated for by a host-dependent parasitic lifestyle. Analysis of the M. leprae genome therefore provides a useful paradigm for all mycobacteria, because of its smaller genome size, obligate intracellularism, and limited complement of genes. The availability of several completely or partially sequenced mycobacterial genomes allows us to dissect the genetics of conserved and dissimilar pathways, such as those for cell-wall biosynthesis.

Retention of the essence of mycobacterial cell walls in M. leprae

Extensive studies of the ultrastructure of the cell wall of M. leprae, both embedded in sections and as whole bacteria isolated from infected tissue in man, mouse, and armadillo, have shown properties common to all mycobacteria: beyond the plasma membrane is a rigid, moderately dense layer composed of an innermost electron-dense layer (probably consisting of peptidoglycan, PG, and arabinogalactan, AG), an intermediate electron-transparent zone (the mycolate layer), and an outermost electron-dense layer (probably composed of assorted lipoglycans, free polysaccharides, glycolipids, and phospholipids) [12,13] (see Figure 2).

A schematic model of the cell envelope of M. leprae. The plasma membrane is covered by a cell-wall core made of peptidoglycan (chains of alternating GlcNAc and MurNGly, linked by peptide crossbridges) covalently linked to the galactan by a linker unit (-P-GlcNAc-Rha-) of arabinogalactan. Three branched chains of arabinan are in turn linked to the galactan. The peptidoglycan-arabinogalactan layer forms the electron-dense zone. Mycolic acids are linked to the termini of the arabinan chains to form the inner leaflet of a pseudo lipid bilayer. An outer leaflet is formed by the mycolic acids of TMM and mycocerosoic acids of PDIMs and PGLs as indicated. The pseudo-bilayer forms the electron-transparent zone. A capsule presumably composed largely of PGLs and other molecules such as PDIMs, PIMs and phospholipids surrounds the bacterium. Lipoglycans such as PIMs, LM and LAM, known to be anchored in the plasma membrane, are also found in the capsular layer as shown. Abbreviations are as used in the text and Box 1.

The underlying framework or 'core' of all mycobacterial cell walls consists of PG, which is covalently attached through a linker unit (LU) (-Rha-GlcNAc-P-) to AG distinguished by furanose sugars (Galf and Araf) [10,14]; the abbreviations we use in the glycoconjugate and sugar names in this review are denned in Box 1. Attached to the terminal Araf units are the mycolic acids (mycolates - (Araf)~30-(Galf)~30-Rha-GlcNAc-P-PG), the lipophilicity of which provides the dominant physiological features of all mycobacteria [15]. Lipoarabinomannan (LAM), lipomannan (LM), the phosphatidylinositol-mannosides (PIMs), cord factor (trehalose dimycolate), sulfolipids, and proteins are associated with this framework in a physical arrangement that is poorly understood [10] (Figure 2).

The limited chemical analysis conducted on the M. leprae cell wall to date suggests that it conforms to this pattern, but with modifications [16]. Small amounts of trehalose monomycolate (TMM) are present, but there is no cord factor [17], and, apparently, M. leprae contains the full complement of PIMs but is devoid of the trehalose-based mycolipenic-acid-containing sulfolipids characteristic of virulent strains of M. tuberculosis. The application of freeze-etching techniques to M. leprae in phagolysosomes isolated from infected human, mouse, and armadillo cells showed large quantities of 'peribacillary substances', which appeared as 'spherical droplets', a feature unique to M. leprae-infected cells [18]. This material proved to be made up of the M. leprae-specific phenolic glycolipids (PGL-I, PGL-II and PGL-III) and the related phthiocerol dimycocerosate (PDIM) [19]. PGL-I consists of the basic phenol-PDIM with the M. leprae-specific trisaccharide (3,6-di-O-Me-Glc)-(2,3-di-O-Me-Rha)-(3-O-Me-Rha) in glycosidic link to the phenol component. Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high titers of antibodies to the trisaccharide unit of PGL-I, and a synthetic derivative has proved useful for serodiagnosis of this condition [20]. Recently, the trisaccharide - notably the terminal 3,6-di-O-Me-GIc unit - was shown to be the M. leprae-specific ligand in the characteristic interaction of M. leprae and Schwann cells, the glial cells of the peripheral nervous system, which are invaded by M. leprae in vivo [21]. This discovery is important as it identified an M. leprae virulence factor that is involved in causing the characteristic nerve damage observed in some leprosy patients. The glycosyltransferases for the synthesis of PGL-I are therefore good candidate drug targets.

Comparative genomics of cell-envelope synthesis

Understanding of the biosynthesis of mycobacterial cell walls is still evolving, and our knowledge to date is confined to understanding individual components of the cell wall separately; the pathways and regulation of final assembly are not understood. The genetics of some of the pathways that have been elucidated in different mycobacterial species, such as M. tuberculosis, M. smegmatis, M. avium or M. bovis, have been compiled in reviews on the mycobacterial cell wall, and putative genes of M. tuberculosis have also been predicted on the basis of homology to genes in other bacteria [22,23]. Here, we update these analyses for various wall components - mycolic acids, polyprenyl phosphates, pepti-doglycan, linker-unit arabinoglycan, mannans and PGL-I - by including and comparing the findings for the condensed genome of M. leprae.

Mycolic acids

The major aspects of acyl-chain elongation leading to the synthesis of mycolic acids in M. tuberculosis have been well-defined and are catalyzed by the two fatty-acid synthases FASI and FASII [25]. The M. leprae genome contains the full complement of the genes encoding FASII enzymes (fabD, acpM, kasA, kasB and accD6). In M. tuberculosis, it has been proposed that the disassociated FASH is primed by lauroyl-CoA generated by FASI, a reaction that is catalyzed by the β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase FabH [26]. We find that there is no apparent FabH homolog in M. leprae, however, pointing to an alternative linking reaction. The lack of methoxymycolates in M. leprae, which was demonstrated previously by chemical analysis, may be explained by the fact that the gene for the responsible methoxymycolic acid synthase (mmaA3) is in fact a pseudogene. The mechanism of condensation of the β chain (from FASI) and the monomycolate chain (from FASII) to form the mature mycolic acid is not yet understood in any mycobacterium. The three mycolyltransferase genes (fbpA, fbpB, and fbpC) in M. tuberculosis that have been implicated in the synthesis of cord factor and also in the transfer of mycolates, to AG, are conserved in M. leprae and incidentally also, at least to some extent, in C. diphtheriae and C. glutamicum (as cps1) [27].

Polyprenyl phosphates

In all mycobacteria, the polyprenyl-P lipid decaprenyl-P (C50-P) is central to all aspects of cell-wall biosynthesis as a carrier of the sugar and/or the biosynthetic intermediates. In PG synthesis, a C50-P-P-MurNGly-pentapeptide intermediate is formed, to which GlcNAc is added followed by transpeptidation and transglycosylation. LU-arabinogalactan is initiated on C50-P [28], by successive addition of the GlcNAc, L-Rhamnose, Galf and Araf, before ligation to PG. The sugar donor for arabinan of AG and LAM is C50-P-Araf while C50-P-Man is a donor for mannan synthesis of LM and LAM [22,23]. A C35-P-Man carrier has been proposed as a carrier of mycolic acids [25].

The precursors of all mycobacterial polyprenyl-Ps, isopentenyl-P-P (IPP) and dimethylallyl-P-P (DMAPP), are generated by the non-mevalonate deoxylulose-5-P (DXP) pathway [29]. In M. tuberculosis, there are two possible genes for DXP synthesis (dxs1 and dxs2), but M. leprae has only dxs1. Other putative genes in the DXP - IPP/DMAPP pathway (dxr, ygbP, ychB and ygbB) are present in both genomes. A non-essential IPP isomerase (idi) is present in Escherichia coli for the interconversion of IPP and DMAPP, and a homolog was found in M. tuberculosis but not in M. leprae. The two isoprenyl-PP synthase genes (Rv1086 and Rv2361c) in M. tuberculosis shown to catalyze the synthesis of decaprenyl phosphate [30] have homologs in M. leprae. Of five other putative isoprenyl diphosphate synthase genes involved in making other isoprenoid molecules in M. tuberculosis, only grcC1 is present in M. leprae. The grcC1 gene is clustered with genes in the menaquinone pathway in both species and may be involved in the prenylation of menaquinone. M. tuberculosis also has genes for sterol synthesis that are absent from M. leprae.

Peptidoglycan

The entire mur operon of E. coli and associated genes involved in PG synthesis have previously been shown to be replicated in M. tuberculosis and M. leprae (ftsZ, ftsQ, murC, murG, ftsW, murD, mraY, murF, murE, and ftsI) [31]. The genes for synthesis of D-alanine and D-glutamic acid from their L-isomers (alr and murI), and for making D-alanine-D-alanine (ddlA) are found in M. leprae. Homologs of the murA and murB are also present, but no good candidate genes encoding key enzymes in mesodiaminopimelic acid synthesis (dapC and dapD) have been found in M. tuberculosis or M. leprae. A hydroxylase for the formation of UDP-MurNGly from UDP-MurNAc has not been identified, and, despite the presence of glycine rather than L-alanine in the peptide crosslinks, M. leprae appears to use the conserved ligase MurC for the addition of glycine or L-alanine to UDP-MurNGly rather than having specialized ligases for the two amino acids [31]. Of the putative M. tuberculosis genes for transpeptidation and/or transglycosylation, two are found in M. leprae (ponA and ponA') and three are pseudogenes.

Linker unit arabinogalactan

Genes required for the synthesis of the sugar donor TDP-rhamnose (rmlA, rmlB, rmlC and rmlD) for the linker unit, and for the synthesis of UDP-Galf(galE and glf) for galactan have been cloned and characterized in M. tuberculosis and are present in M. leprae [32,33]. The arabinose donor for AG is the novel C50-P-Araf, which is probably derived by the epimerization of the ribose in 5-phosphoribose pyrophos-phate followed by transfer to a C50-P [34]. Rv3808c (glfT) of M. tuberculosis encodes a bifunctional galactosyl transferase responsible for adding both the 5- and 6-linked Galf sugars during galactan polymerization [35,36]. There is an ortholog of Rv3808c in a similar genetic context in M. leprae (as described below).

The embA and embB genes of M. avium that confer resistance to ethambutol in M. smegmatis have been implicated as arabinosyl transferases; and there is an additional embC gene in M. tuberculosis [37]. These homologous genes are conserved among many mycobacteria and are intact in M. leprae within a gene cluster proposed to be involved in several aspects of AG synthesis [23]. This putative AG cluster of M. tuberculosis (Rv3781-Rv3809c) includes genes homologous to O-antigen export proteins (Rv3781, Rv3783), unknown glycosyltransferases (Rv3782, Rv3789), mycolyl-transferase (fbpA) and galactan genes (glfT and glf) (Figure 3). Except for three genes of unknown function, this cluster is present in M. leprae. Interestingly, in the unfinished genome of C. diphtheriae, this cluster was also found to a large extent, but it appears to be split between two contigs: one contains portions of Rv3781-Rv3793 (which includes the O-antigen export proteins and has only one emb gene); the other contains all the 11 genes Rv3799c-Rv3809c (including homologs for fbpA, glf and glfT).

Genetic organization of the putative AG biosynthetic cluster in M. tuberculosis [23] and identification of a similar cluster in M. leprae and C. diphtheriae. The M. tuberculosis genes are represented by a letter (A-AC), along with an Rv number or a gene name as annotated in the SangerCentre M. tuberculosis database [4]. Genes D, E, F, G, P and R (asterisked) are absent from both M. leprae and C. diphtheriae. In C. diphtheriae, homologs of genes S-AC and A-M were found on two different contigs (represented here as I and II). M. leprae fadE35 (Q; dotted arrow) is a pseudogene.

Mannans

The pgsA gene (previously called pis) for the synthesis of the PI core of PIMs, LM and LAM was identified in an operon consisting of an acyltransferase and mannosyltransferase in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis and was shown to be essential in the latter [38]. M. leprae has a similar operon. In M. tuberculosis, it has been shown that after PIM1 is made by an unknown mannosyltransferase, the gene pimB, which encodes the second mannosyltransferase, is responsible for synthesis of PIM2, the precursor of LM and LAM [39]. Peculiarly, pimB is a pseudogene in M. leprae. The mannose donor for the synthesis of the bulk of the mannan of LM and LAM is C50-P Man [40] and the mannosyl-transferase gene responsible for its synthesis has been identified in both M. tuberculosis (Rv2051c) and M. leprae.

PGL-I

In M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG, a cluster of genes for the synthesis of phthiocerol, mycocerosoic acids, their liga-tion and transport to the cell wall have been characterized (fadD26, ppsA-E, drrA-C, papA5, mas, fadD28 and mmpL7) [41,42]. Interestingly, in M. leprae, the genes for phthiocerol synthesis are intact but have been separated from those for mycocerosic-acid synthesis. We have identified putative genes responsible for the synthesis of the three sugars in PGL-I (for details see Table 1). The associated methyltransferase genes are analogous to those associated with glycopeptidolipid synthesis in M. avium [43,44].

As described above, we know little about the glycosyltransferases involved in the synthesis of the mycobacterial cell wall such as mannosyltransferases for LM and LAM biosynthesis, rhamnosyl and glycosyltransferases for PGL-I and polyprenyl-P-glycosyltransferases (for C50-P-Araf). By combining information from annotations in the genome databases of M. tuberculosis and M. leprae [2,4] with the results of BLAST and RPS-BIAST searches [24] and with what is known about some glycosyltransferases (such as pimB and glfT), we have compiled a list of glycosyltransferases from the genomes of M. leprae and M. tuberculosis and tentatively assigned certain functions to them (see Table 1). Also included in the searches were the unfinished genomes of M. avium, C. diphtheriae and M. bovis. Such comparative genome analysis should also be helpful in identifying genes for species-specific pathways such as the pathway for sulfolipid found in virulent strains of M. tuberculosis.

Analysis of the genes involved in similar pathways across all mycobacterial genomes and Corynebacterium will facilitate a complete understanding of the physiology of Mycobacterium, Corynebacterium and Nocardia, including knowledge about their cell walls, the most characteristic and yet most obscure features of these pathogens. This will allow identification of novel drug targets, formulation of vaccines, and development of new diagnostics. The sequencing of a Rhodococcus genome will be a welcome addition. In the case of M. leprae, recombinant-protein expression and proteomics will further our understanding, because, as of today, there are no genetic tools for manipulating this pathogen. It will be some time before the insights from comparative genomics of mycobacteria yields benefits to medicine, but we can be hopeful that they are guiding us in the right direction.

References

Cole ST, Eiglmeier K, Parkhill J, James KD, Thomson NR, Wheeler PR, Honore N, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, et al: Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature. 2001, 409: 1007-1011. 10.1038/35059006.

The Mycobacterium leprae genome project. [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_leprae/]

Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, et al: Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998, 393: 537-544. 10.1038/31159.

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome project. [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_tuberculosis/]

The Institute for Genomic Research. [http://www.tigr.org]

The Mycobacterium bovis genome project. [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_bovis/]

The Mycobacterium paratuberculosis genome project. [http://www.cbc.umn.edu/ResearchProjects/AGAC/Mptb/Mptbhome.html]

The Corynebacterium diphtheriae genome project. [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_diphtheriae]

Russell DG: Mycobacterium and the seduction of the macrophage. In Mycobacteria. Molecular Biology and Virulence. Edited by Ratledge C, Dale J: Oxford: Blackwell Science;. 1999, 371-388.

Belisle JT, Brennan PJ: Mycobacteria. In Encyclopedia of Microbiology. SanDiego: Academic Press,. 2000, 312-327.

Hastings RC, Gillis TP, Krahenbuhl JL, Franzblau SG: Leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988, 1: 330-348.

Hirata T: Electron microscopic observations of cell wall and cytoplasmic membrane in murine human leprosy bacilli. Int J Lepr. 1985, 53: 433-440.

Draper P: The bacteriology of Mycobacterium leprae. Tubercle. 1983, 64: 43-56.

McNeil M, Daffe M, Brennan PJ: Evidence for the nature of the link between the arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan of mycobacterial cell walls. J Biol Chem. 1990, 265: 18200-18206.

McNeil M, Daffe M, Brennan PJ: Location of the mycolyl ester substituents in the cell walls of mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 1991, 266: 13217-13223.

Daffe M, McNeil M, Brennan PJ: Major structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactans of Mycobacterium, Rhodococcus, and Nocardia spp. Carbohydr Res. 1993, 249: 383-398. 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84102-C.

Dhariwal KR, Yang YM, Fales HM, Goren MB: Detection of tre-halose monomycolate in Mycobacterium leprae grown in armadillo tissues. J Gen Microbiol. 1987, 133: 201-209.

Fukunishi Y: Electron microscopic findings of the peripheral nerve lesions of nude mouse inoculated with M. leprae perineural lesions. Int J Lepr. 1988, 56: 501-

Hunter SW, Brennan PJ: A novel phenolic glycolipid from Mycobacterium leprae possibly involved in immunogenicity and pathogenicity. J Bacteriol. 1981, 147: 728-735.

Brennan PJ, Chatterjee D, Fujiwara T, Cho S-N: Leprosy-specific neoglycoconjugates: synthesis and application to serodiagnosis of leprosy. Methods Enzymol. 1994, 242: 27-37.

Rambukkana A: Molecular basis for the peripheral nerve predilection of Mycobacterium leprae. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001, 4: 21-27. 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00159-4.

Baulard AR, Besra GS, Brennan PJ: The cell-wall core of Mycobacterium: structure, biogenesis and genetics. In Mycobacteria. Molecular Biology and Virulence. Edited by Ratledge C, DaleJ. Oxford: Blackwell Science;. 1999, 240-259.

Belanger AE, Inamine JM: Genetics of cell wall biosynthesis. In Molecular Genetics of Mycobacteria. Edited by Hatfull GF, Jacobs WR Jr. Washington, DC: ASM Press;. 2000, 191-202.

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ: Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 3389-3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389.

Barry CE, Lee RE, Mdluli K, Sampson AE, Schroeder BG, Slayden RA, Yuan Y: Mycolic acids: structure, biosynthesis and physiological functions. Prog Lipid Res. 1998, 37: 143-179. 10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00008-3.

Choi KH, Kremer L, Besra GS, Rock CO: Identification and substrate specificity of beta-ketoacyl (acyl carrier protein) syn-thase III (mtFabH) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 28201-28207.

Puech V, Bayan N, Salim K, Leblon G, Daffe M: Characterization of the in vivo acceptors of the mycoloyl residues transferred by the corynebacterial PS1 and the related mycobacterial antigens 85. Mol Microbiol. 2000, 35: 1026-1041. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01738.x.

Mikusova K, Mikus M, Besra GS, Hancock I, Brennan PJ: Biosynthesis of the linkage region of the mycobacterial cell wall. J Biol Chem. 1996, 271: 7820-7828. 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7820.

Crick DC, Brennan PJ: Antituberculosis drug research. Curr Opin Anti-Infect Invest Drugs. 2000, 2: 154-163.

Schulbach MC, Brennan PJ, Crick DC: Identification of a short (C15) chain Z-isoprenyl diphosphate synthase and a homologous long (C50) chain isoprenyl diphosphate synthase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 22876-22881. 10.1074/jbc.M003194200.

Mahapatra S, Crick DC, Brennan PJ: Comparison of the UDP-N-acetylmuramate:L-alanine ligase enzymes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae. J Bacteriol. 2000, 182: 6827-6830. 10.1128/JB.182.23.6827-6830.2000.

Ma Y, Stern RJ, Scherman MS, Vissa VD, Yan W, Jones VC, Zhang F, Franzblau SG, Lewis WH, McNeil MR: Drug targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall synthesis: genetics of dTDP-rhamnose synthetic enzymes and development of a microtiter plate-based screen for inhibitors of conversion of dTDP-glucose to dTDP-rhamnose. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001, 45: 1407-1416. 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1407-1416.2001.

Weston A, Stern RJ, Lee RE, Nassau PM, Monsey D, Martin SL, Scherman MS, Besra GS, Duncan K, McNeil MR: Biosynthetic origin of mycobacterial cell wall galactofuranosyl residues. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997, 78: 123-131.

Scherman MS, Kalbe-Bournonville L, Bush D, Xin Y, Deng L, McNeil M: Polyprenylphosphate-pentoses in mycobacteria are synthesized from 5-phosphoribose pyrophosphate. J Biol Chem. 1996, 271: 29652-29658. 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29652.

Mikusova K, Yagi T, Stern R, McNeil MR, Besra GS, Crick DC, Brennan PJ: Biosynthesis of the galactan component of the mycobacterial cell wall. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 33890-33897. 10.1074/jbc.M006875200.

Kremer L, Dover LG, Morehouse C, Hitchin P, Everett M, Morris HR, Dell A, Brennan PJ, McNeil MR, Flaherty C, et al: Galactan biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis : identification of a bifunctional UDP-galactofuranosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 26430-26440. 10.1074/jbc.M102022200.

Belanger AE, Besra GS, Ford ME, Mikusova K, Belisle JT, Brennan PJ, Inamine JM: The embAB genes of Mycobacterium avium encode an arabinosyl transferase involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis that is the target for the antimycobacterial drug ethambutol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93: 11919-11924. 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11919.

Jackson M, Crick DC, Brennan PJ: Phosphatidylinositol is an essential phospholipid of mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 30092-30099. 10.1074/jbc.M004658200.

Schaeffer ML, Khoo KH, Besra GS, Chatterjee D, Brennan PJ, Belisle JT, Inamine JM: The pimB gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a mannosyltransferase involved in lipoarabinomannan biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 31625-31631. 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31625.

Besra GS, Morehouse CB, Rittner CM, Waechter CJ, Brennan PJ: Biosynthesis of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 18460-18466. 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18460.

Azad AK, Sirakova TD, Fernandes ND, Kolattukudy PE: Gene knockout reveals a novel gene cluster for the synthesis of a class of cell wall lipids unique to pathogenic mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 16741-16745. 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16741.

Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, Laneelle MA, Triccas JA, Gicquel B, Daffe M, Guilhot C: Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability barrier. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 19845-19854. 10.1074/jbc.M100662200.

Belisle JT, Pascopella L, Inamine JM, Brennan PJ, Jacobs WR: Isolation and expression of a gene cluster responsible for biosynthesis of the glycopeptidolipid antigens of Mycobacterium avium. J Bacteriol. 1991, 173: 6991-6997.

Eckstein TM, Silbaq FS, Chatterjee D, Kelly NJ, Brennan PJ, Belisle JT: Identification and recombinant expression of a Mycobacterium avium rhamnosyltransferase gene (rtfA) involved in glycopeptidolipid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998, 180: 5567-5573.

Acknowledgements

Research conducted in the authors' laboratory was supported by NIH, NIAID, DMID Contract NO I AI-55262 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and by the Heiser Program for Research in Leprosy and Tuberculosis, New York City, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vissa, V.D., Brennan, P.J. The genome of Mycobacterium leprae: a minimal mycobacterial gene set. Genome Biol 2, reviews1023.1 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-reviews1023

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-reviews1023