Abstract

Introduction

Selective digestive decontamination (SDD) appears to have a more compelling evidence base than non-antimicrobial methods for the prevention of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). However, the striking variability in ventilator associated pneumonia-incidence proportion (VAP-IP) among the SDD studies remains unexplained and a postulated contextual effect remains untested for.

Methods

Nine reviews were used to source 45 observational (benchmark) groups and 137 component (control and intervention) groups of studies of SDD and studies of three non-antimicrobial methods of VAP prevention. The logit VAP-IP data were summarized by meta-analysis using random effects methods and the associated heterogeneity (tau2) was measured. As group level predictors of logit VAP-IP, the mode of VAP diagnosis, proportion of trauma admissions, the proportion receiving prolonged ventilation and the intervention method under study were examined in meta-regression models containing the benchmark groups together with either the control (models 1 to 3) or intervention (models 4 to 6) groups of the prevention studies.

Results

The VAP-IP benchmark derived here is 22.1% (95% confidence interval; 95% CI; 19.2 to 25.5; tau2 0.34) whereas the mean VAP-IP of control groups from studies of SDD and of non-antimicrobial methods, is 35.7 (29.7 to 41.8; tau2 0.63) versus 20.4 (17.2 to 24.0; tau2 0.41), respectively (P < 0.001). The disparity between the benchmark groups and the control groups of the SDD studies, which was most apparent for the highest quality studies, could not be explained in the meta-regression models after adjusting for various group level factors. The mean VAP-IP (95% CI) of intervention groups is 16.0 (12.6 to 20.3; tau2 0.59) and 17.1 (14.2 to 20.3; tau2 0.35) for SDD studies versus studies of non-antimicrobial methods, respectively.

Conclusions

The VAP-IP among the intervention groups within the SDD evidence base is less variable and more similar to the benchmark than among the control groups. These paradoxical observations cannot readily be explained. The interpretation of the SDD evidence base cannot proceed without further consideration of this contextual effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colonization and infection with bacteria occurs commonly in patients receiving mechanical ventilation (MV) [1–5]. The use of selective digestive decontamination (SDD) is an approach to prevent colonization and pneumonia in this patient group [6]. Systematic reviews of more than 30 controlled studies of SDD provide compelling evidence of reductions in VAP of >50% [6] versus marginally significant reductions of <20% with non-antibiotic methods of prevention such as those based on the management of gastric pH [7], tracheal suction [8], or humidification [9].

That SDD could create a contextual effect in the intensive care unit through cross colonization between patients of concurrent control and study groups was postulated in the original 1984 study [10] and others [11], which were intentionally non-concurrent in design. This postulate remains untested. Moreover, the VAP-IP of control groups of SDD studies is highly variable, particularly among SDD studies with a concurrent design [12]. To account for this variability and to test the original postulate would require an external benchmark of VAP-IP.

Four recent factors enable a benchmarking of the VAP-IP among the component groups of the SDD evidence base. First, five reviews [1–5] have independently estimated the expected VAP-IP range for observational groups and enable the derivation of a benchmark. Second, the key studies in the evidence base for SDD and for comparison, three non-antibiotic methods of VAP prevention, are identified in four large systematic reviews [6–9]. Third, various group level factors, which may be explanatory toward the VAP incidence, are identified in all of the studies. Finally, heterogeneity among study results can now be measured and incorporated in the derivation of a prediction range using recently developed random effects methods of meta-analysis and displayed using a caterpillar plot [13, 14].

Materials and methods

Overview

There are four objectives here: First, to derive a VAP-IP benchmark and prediction range derived from observational (benchmark) groups. Second, to summarize VAP-IP separately for the control and intervention groups from studies of two broad approaches to VAP prevention that have been included in systematic reviews; studies of SDD versus studies of non-anti-microbial methods of VAP prevention. Third, to assess the dispersion among the group specific VAP-IP of control groups and intervention groups versus the VAP-IP benchmark using caterpillar plots. Finally, to assess the impact of group level factors as possible explanatory variables toward the group specific VAP-IP in meta-regression models that include both the benchmark and the prevention study groups.

Study selection and component group designations

This analysis is limited to component groups from studies of patients receiving mechanical ventilation as abstracted in nine published reviews (four non-systematic and five systematic) of VAP incidence and specific VAP prevention methods [1–9]. The unit of analysis here is the component patient group, whether observational (benchmark) [1–5], or control or intervention groups from studies of various methods of VAP prevention [6–9].

The inclusion criterion for this analysis was a study of adult patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation in intensive care units (ICUs) for which VAP-IP and denominator data had been abstracted in one of the nine reviews [1–9]. The exclusion criteria as specified in the Cochrane review [6] are applied to achieve harmonization across the studies obtained from all nine reviews. That is; studies based on specific pre-selected types of patients (patients undergoing elective esophageal resection, cardiac or gastric surgery, liver transplant or suffering from acute liver failure), studies of non-ICU populations, populations for which the proportion receiving MV for >24 hours was <50% and studies for which VAP-IP data were not available. Also, studies of pediatric populations, and studies published before 1984 do not appear among the studies abstracted in the review of Liberati et al. [6] and these study types are also excluded.

Categories of benchmark and component groups

The benchmark groups are those groups of observational studies as abstracted in one of five reviews of VAP incidence [1–5]. Any intervention study abstracted in one of these five reviews of VAP-IP incidence was not used in the derivation of the benchmark.

The component groups of studies of non-antimicrobial methods of VAP prevention are as abstracted in one of three systematic reviews of various methods of gastric acid suppression [7], open versus closed methods of tracheal suction [8], or passive versus active humidification [9] as methods of VAP prevention. In the gastric acid studies, the interventions studied were those that might suppress gastric acid (for example, ranitidine or antacid treatment) versus interventions that did not (for example, no treatment or sucralfate) [7]. The designation of control and intervention groups were as indicated in the systematic reviews of open (control) versus closed (intervention) methods of tracheal suction [8] and passive (HH, control) versus active (HME, intervention) humidification [9]. The component groups from the studies of SDD are as abstracted in the Cochrane review [6].

Data extraction

The primary outcome is the VAP-IP, which is the incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia per 100 patients. The VAP-IP and its denominator were taken for all component groups as abstracted in the review documents in which they appeared.

Additional information abstracted directly from the original publication was whether the mode of VAP diagnosis required bronchoscopic sampling versus tracheal sampling methods, whether <90% of patients received at least 24 hours of mechanical ventilation, and the proportion of patients admitted to the ICU for trauma. The scoring of study quality was also abstracted from each systematic review. However, each systematic review used different quality scoring systems and scoring was not used in the non-systematic reviews. The indicator of highest study quality in this analysis was whether the study received a majority score in the source systematic review. Data were extrapolated from tables and figures if not available in the text. Care was taken to stratify patient groups appearing across more than one publication.

Caterpillar plots

A caterpillar plot is a forest plot-like display of group specific odds and 95% confidence intervals with the studies listed in rank order of increasing event rate. This display reveals both the overall symmetry of the individual group results and their deviation from the overall mean. This display shows the impact of group size with the larger groups, having greater precision, expected to deviate less from the summary or benchmark.

Statistical methods

The VAP-IP data were converted to logits for analysis as follows; if D represents the denominator, N represents the numerator, and R represents the proportion (N/D) of the VAP-IP, the logit(VAP-IP) is log(N/(D-N)) and its variance is 1/(D*R*(1-R)) [15, 16]. This variance formula was used to calculate the group specific 95% confidence intervals. Using these calculated logits and logit variances, the metan command [17] in STATA (release 11.0, STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA) generates summary logits by a random effects method together with the standard errors (SE) and tau2, which are measures of within and between group variances, respectively, and the associated 95% CI's. The metan command also generates the caterpillar plots of the group specific logits and 95% CI's.

The VAP-IP benchmark was derived as the mean logit VAP-IP and 95% confidence interval derived together with a 95% prediction interval. The later is calculated using the metan command as mean ± 1.96 * (SE2 + tau2)0.5 [17]. In each of the caterpillar plots, both the overall VAP-IP mean derived from the groups in the plot and the 95% prediction interval derived from VAP-IP benchmark range are displayed.

To test the stability of the benchmark, five replicate derivations of the VAP-IP benchmark were derived using the VAP-IP data abstracted from the four non-systematic and one systematic reviews individually [1–5].

Meta-regression

The calculated logits and logit variances were used with the metareg command [18] in STATA (release 11.0, STATA Corp.) to perform meta-regression models that incorporate group level factors as predictors. There are six meta-regression models of logit VAP-IP including the benchmark groups with either the control (models 1 to 3) or the intervention (models 4 to 6) groups of the prevention studies. Models 1 and 4 include group membership (benchmark, SDD study or non-antimicrobial method study), as the only predictors. Models 2 and 5 include three additional group level properties as predictor variables; whether <90% of patients in the group received >24 hours of MV, whether the mode of diagnosis of VAP required bronchoscopic sampling and the proportion of trauma admissions to the ICU. Models 3 and 6 replicate models 2 and 5 but are limited to those studies that had received majority quality scores in the source systematic reviews. Regression coefficients were compared using the lincom (linear combination) post-estimation command in STATA.

Sensitivity analysis

Meta-regressions models 2 and 4 were repeated after exclusion of studies for which the proportion of patients receiving >24 hours of mechanical ventilation was <90% or unknown. Also, meta-regressions models 3 and 6 were repeated with component groups from 19 studies of SDD that had received a quality score of one out of two included.

Results

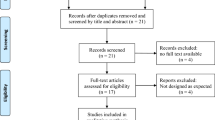

There were 45 observational benchmark groups (Additional file 1) [19–63] and 137 component groups (Additional files 2 and 3) [64–131] derived from nine reviews [1–9]. The characteristics of the studies and the groups are summarized in Table 1. Most studies had been published in the 1990's. Compared to the benchmark groups, the component groups of the studies of VAP prevention methods differed in the following respects; they had fewer patients per group (P = 0.001), fewer had bronchoscopic sampling performed for VAP diagnosis (P = 0.003) and admissions for trauma among them were more frequent (P = 0.01). The studies of non-antimicrobial methods more often attained majority quality scores than did studies of SDD in the respective systematic reviews (P = 0.006).

The VAP-IP benchmark derived from all 45 observational (benchmark) groups is 22.1% with a 95% confidence interval of 19.0% to 25.5%, and with a 95% prediction interval of 8.6% to 47.3% (Figure 1). The five replicate estimates of the benchmark using the abstracted VAP-IP data from the observational (benchmark) groups abstracted in each of the four non-systematic and one systematic reviews were each within five percentage points of the benchmark derived using the abstracted VAP-IP data from all 45 observational (benchmark) groups (Table 2). Among the benchmark groups, there was no significant trend in VAP-IP versus publication year (data not shown, P = 0.47). A summary VAP-IP derived from benchmark groups originating from European centres and non-European centres were each within two percentage points of the benchmark (Table 2).

Caterpillar plot: observational (benchmark) groups and derived benchmark. Caterpillar plot of the group specific (small diamonds) VAP-IP and 95% CI of observational benchmark groups together with the summary VAP-IP (dotted green vertical line), 95% CI (large open diamond) and 95% prediction interval (solid green horizontal line). Note that the x axis is a logit scale. The VAP-IP data is as abstracted in four non-systematic and one systematic review [1–5].

The group specific and summary VAP-IP's for the component groups of the prevention studies are displayed in Figures 2, 3, 4, 5 and the summary VAP-IPs are tabulated in Table 3. The I2 associated with the summary estimates ranged between 74% and 93%. The distribution of the group specific VAP-IPs of the control groups of the SDD studies differs in five ways versus the distribution of the group specific VAP-IPs among the control groups of the studies of non-antibiotic methods; the mean and tau2 are 50% higher (Table 3) and the interquartile range (IQR) (Table 1) and confidence intervals (Table 3) are both 50% wider. Moreover, the median VAP-IP (Table 1) of the control groups of the SDD studies is more than five percentage points higher than the mean (Table 3), a finding which indicates a positive skew.

Caterpillar plot: control groups of studies of non-antimicrobial methods of VAP prevention. Caterpillar plot of the group specific (small diamonds) and summary (broken vertical line) VAP-IP and 95% CI (large open diamond) of control groups of studies of non-antimicrobial methods of VAP prevention. The VAP-IP data is as abstracted in three systematic reviews [7–9]. For comparison, the VAP-IP benchmark (solid green vertical line) and prediction interval (solid green horizontal line) derived from the benchmark groups from Figure 1 is also shown. Note that the x axis is a logit scale.

Caterpillar plot: intervention groups of studies of non-antimicrobial methods of VAP prevention. Caterpillar plot of the group specific (small diamonds) and summary (broken vertical line) VAP-IP and 95% CI (large open diamond) of intervention groups of studies of non-antimicrobial methods of VAP prevention. The VAP-IP data is as abstracted in three systematic reviews [7–9]. For comparison, the VAP-IP benchmark (solid green vertical line) and prediction interval (solid green horizontal line) derived from the benchmark groups from Figure 1 is also shown. Note that the x axis is a logit scale.

Caterpillar plot: control groups of SDD studies. Caterpillar plot of the group specific (small diamonds) and summary (broken vertical line) VAP-IP and 95% CI (large open diamond) of control groups of SDD studies. Four control groups from duplex studies that is, all control group patients routinely received systemic antibiotics, are indicated by an asterix next to the author name and NC indicates non-concurrent. The VAP-IP data is as abstracted in Liberati et al. [6]. For comparison, the VAP-IP benchmark (solid green vertical line) and prediction interval (solid green horizontal line) derived from the benchmark groups from Figure 1 is also shown. Note that the x axis is a logit scale.

Caterpillar plot: intervention groups of SDD studies. Caterpillar plot of the group specific (small diamonds) and summary (broken vertical line) VAP-IP and 95% CI (large open diamond) of intervention groups of SDD studies. The VAP-IP data is as abstracted in Liberati et al.[6]. For comparison, the VAP-IP benchmark (solid green vertical line) and prediction interval (solid green horizontal line) derived from the benchmark groups from Figure 1 is also shown. Note that the x axis is a logit scale.

The differences in distributions of VAP-IP among the component groups of the prevention studies are also apparent in the caterpillar plots (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5) in that 11 of the 33 control groups of the SDD studies versus only 3 of the 35 control groups of the non-antibiotic studies have group specific VAP-IP's which are above the benchmark 95% prediction interval. Four of the control groups with VAP-IP within the benchmark prediction range were control groups from SDD studies that had a duplex design; that is, all control group patients routinely received systemic antibiotics.

The disparities in summary VAP-IP among the component groups of the prevention studies versus the benchmark remained apparent in analyses limited to the highest quality studies (Table 3). The mean VAP-IP of the control groups of highest quality SDD studies were 22 percentage points higher than the benchmark. By contrast, for all other component groups the summary VAP-IP's were within seven percentage points of the benchmark whether derived from the highest quality studies or all studies.

Meta-regression models

Three meta-regression models were performed as described in the methods to evaluate several group level properties as predictors of the group specific logit VAP-IP's of the control (Table 4) and intervention (Table 5) groups versus the benchmark groups.

For the control groups versus the benchmark groups (Table 4; meta-regression models 1 to 3), membership of a control group of an SDD study was a consistently positive predictor. For the intervention groups versus the benchmark groups (Table 5; meta-regression models 4 to 6), membership of an intervention group of an SDD study was a negative predictor of logit VAP-IP but not consistently significant.

In comparing these factors in the meta-regression models, membership of a control group of an SDD study differed significantly versus membership of a control group of a non-antibiotic study in model 1 (P < 0.001), model 2 (P < 0.001) and model 3 (P = 0.003). By contrast, membership of an intervention group of an SDD study did not differ significantly versus membership of an intervention group of a non-antibiotic study as a predictor in model 4 (P = 0.7), model 5 (P = 0.6) or model 6 (P = 0.3).

Meta-regressions models 2 and 4 were repeated after exclusion of studies for which the proportion of patients receiving >24 hours of mechanical ventilation was <90% or unknown. Also, meta-regressions models 3 and 6 were repeated with component groups from 19 studies of SDD that had received a quality score of one out of two included. With both of these re-analyses, the findings were replicated (data not shown).

Discussion

The present analysis has identified unexplained and paradoxical discrepancies among the VAP-IP of control groups and the intervention groups of SDD studies versus the benchmark and versus groups of other studies aggregated from reviews of other methods of VAP prevention. There were several analytic and statistical issues that needed to be addressed to execute this analysis.

The first analytic issue is the method of study selection. The objective here was to evaluate the evidence base as represented within systematic and other reviews. Hence a new literature search was not undertaken but the analysis was specifically limited to studies identified in nine published reviews and to the use of those studies exclusively. This narrowed focus allows scrutiny of the component groups that form an entire evidence base [6–9]. The three systematic reviews of non-antibiotic methods of VAP prevention were chosen because they were the largest available.

The second analytic issue is the method of abstracting VAP-IP data. The use of abstracted data from the reviews rather than from the published studies maintains objectivity and facilitates independent verification as all the data is readily identifiable in the reviews. Of note, the method of VAP-IP abstraction for the SDD review [6] was somewhat unique in that these authors had contacted investigators of the original SDD studies to obtain 'intention to treat' data. Hence, the SDD data includes missing data for 25 of the 36 SDD studies with published data used for the remaining 11 studies. However, applying the benchmark 95% prediction range to the VAP-IP data as published in all 33 studies yields similar discrepancies [12].

The third analytic issue is that the VAP-IP is proportion data arising from groups with varying denominators. Transformation to logits and weighting by the inverse variance as a method of adjusting for variable study size are standard methods for analysis of proportion data [15, 16].

The fourth issue is that the studies vary considerably in the intervention under study. It should be noted that profiling the component groups of the prevention studies against the benchmark is the objective of the analysis here rather than estimating the summary effect size for the interventions under study. In this regard, the control groups are of particular interest. If there is no contextual effect associated with the study of SDD within an ICU, it would be expected that the control groups of concurrent design SDD studies would have VAP-IP's similar not only to each other, but to the benchmark and also to the VAP-IP's of control groups of studies of other prevention methods.

The fifth issue is that the quality scores of the studies as rated in each systematic review varied. Also, different scales of study quality were used in each of the systematic reviews. As a consequence, a majority quality score as rated by each systematic review was used as a unified rating of highest study quality. Paradoxically, the disparities in VAP-IP noted here are most apparent in comparisons limited to the highest quality studies.

The sixth issue is the heterogeneity (over-dispersion) in event rates arising from different patient populations in different centres. This is apparent in all of the summary ranges here in that all have I2 values above 75% which indicate high levels of heterogeneity [132]. Heterogeneity has been a major obstacle in the context of profiling the performance of hospitals and surgeons toward the identification of individual outlier performers. Adjusting for patient risk is an important consideration in profiling, but this is problematic when comparing multiple centres [133]. It should be noted that identification of individual outlier performers is not an objective of this analysis but rather the estimation of the overall VAP-IP range among the component groups that comprise an entire evidence base and the identification of group level explanatory variables in the meta-regression models of VAP-IP.

A more recent development in relation to managing heterogeneity is to measure it using random effects methods [13, 14, 132]. With random effects methods, both the variance arising from between groups (heterogeneity, tau2) versus that from within groups (sampling, SE) are estimated and both types of variability are incorporated in the calculation of the 95% prediction intervals with as a result, more conservative (wider) prediction intervals than would be derived using traditional fixed effects methods which do not take heterogeneity into account.

There were 19 different topical SDD intervention regimens studied. The most common regimen used in the studies included here was a topical combination of polymyxin, tobramycin and amphotericin together with, for 13 of the SDD intervention groups, a parenteral antibiotic [134]. Given the heterogeneity in the SDD treatments, surprisingly the IQR (Table 1) was wider and the tau2 (Table 3) was higher for the control groups of the SDD studies than for the corresponding intervention groups and also versus the control and intervention groups of studies of three different types of non-antibiotic prevention methods. These are paradoxical findings.

The seventh issue is observer bias and the lack of an objective gold standard for VAP. In part this issue relates to study design and the blinding of observers and adequate concealment of group allocation, factors that have been assessed as part of the study quality ratings used in each of the systematic reviews. More particularly, lack of an objective gold standard is an important issue in the case of VAP for which there are several definitions in use, with those that require bronchoscopic based sampling being possibly a more specific but less sensitive diagnostic standard [135].

Additional to this is that some of the studies included patients who were not ventilated, which is problematic for the diagnosis of VAP. Also, the proportion of patients admitted for trauma, used here as a surrogate for the patient mix, ranged between 0% and 100% among the studies. These issues in VAP diagnosis have been identified as group level factors in meta-regression models 2, 3, 5 and 6.

Limitations of this analysis

There are several limitations of this analysis. The random effects method of analysis presumes that the groups in each summation are representative of a 'random' selection of an undefinable super-population of groups. The VAP-IP benchmark derived here may only be representative of patient groups as found within systematic reviews.

Only nine reviews were used in this analysis and other smaller reviews have not been included. However, other reviews applicable to this patient group can be tested against the 95% prediction range derived from the benchmark groups here. For example, systematic reviews of kinetic bed [136] therapy and topical chlohexidene [137] as methods for the prevention of VAP had identified 10 and 7 studies respectively. Of the 17 studies identified in these two systematic reviews, only two studies, one from each systematic review, had a control group with a VAP-IP above 47.3%, the upper 95% limit of the prediction range derived from the benchmark groups here, whereas three had an intervention group VAP-IP below the lower 95% limit of the prediction range derived from the benchmark groups.

Also, studies of SDD which had a non-concurrent design have not been included in the meta-regression. This would help to test the postulated contextual effect of SDD. Among the SDD studies included here, three have a third non-concurrent control group arm in addition to the two concurrent arms [101, 104, 131]. The VAP-IP of all three of these non-concurrent control groups is less than 24% [12].

A further limitation was that the number of group level factors that could be explored was limited by those that were readily available and identified for all the groups in the analysis. Origin from a European country and year of publication were tested and found not to be significant in preliminary analyses (data not shown). Other factors such as the prevalence of antibiotic use have not been explored beyond that accounted for by duplex study design. Also the duration of mechanical ventilation has not been considered beyond the group average, which appeared to be similar across the strata (Table 1). The appropriate investigation of these factors would require patient level data to control for the possible influence of ecological bias [138].

There are three possible interpretations of these paradoxical findings. First, publication and citation bias need to be considered. Deriving the benchmark from four non-systematic and one systematic reviews was done to test the stability of the benchmark estimate (Table 2). In replications of the benchmark range from these five reviews separately this varies by no more than five percentage points.

Given that 11 of the 33 control groups from studies of SDD are above the upper limit of the 95% prediction range of the benchmark where only 2.5% of the distribution would be predicted to be found, this could be taken to indicate a deficit of 407 groups below the upper limit of the 95% prediction range of the benchmark {407 = (11 * 97.5/2.5)- 22)}. This estimate corresponds to an earlier test for publication bias using a funnel plot method which indicated a deficit of >500 'inlier' groups with VAP-IP < 45% from studies of SDD that had been unpublished or were otherwise 'missing' [12].

A second interpretation is that the possible impacts of unmeasured and unknown patient level risk factors for VAP-IP have not been evaluated in this analysis. However, for such a risk factor to account for the discrepancies between the VAP-IP of the control groups of SDD studies versus the benchmark groups is unlikely. Such putative risk factors would need to be consistently strong across the range of studies and yet have a profoundly uneven distribution between the SDD studies versus other studies. This is in contrast to the inconsistent strength and direction of the known VAP risk factors [2, 3].

For example, duration of mechanical ventilation is the strongest patient level risk factor for VAP with increases of approximately 2 per 100 patients per day of ventilation during the second week of ventilation [139]. The discrepancies in VAP-IP noted here between the control groups of SDD studies versus the benchmark would equate to a difference in mean duration of ventilation across all groups of 6.8 days.

A third interpretation is a possible contextual effect of SDD. The possibility of contextual effects due to cross colonization and infection within the ICU environment resulting from SDD use as was postulated in the original study of SDD [10] needs to be considered [140]. SDD is known to alter the colonization among recipients [141, 142]. However, identifying cross colonization within a single study is difficult. A major limitation toward testing this postulate is that colonization pressure [143] and cross colonization, two crucial intermediary steps, have not been measured in any of these studies.

Conclusions

The VAP-IP among control groups of SDD studies is more variable and the mean is >50% greater than other groups within the evidence base including the VAP benchmark. These paradoxical findings cannot be accounted for through group level adjustments for proportion of trauma admissions, mode of VAP diagnosis and proportion of patients receiving prolonged ventilation.

Apart from major publication bias, or the effect of a major and as yet unidentified and mal-distributed patient level VAP risk factor, or the effect of in-apparent outbreaks [140], these paradoxical discrepancies cannot be explained. The interpretation of the studies of SDD treatments cannot proceed without further consideration that SDD may have a contextual effect as originally postulated [10].

Key messages

-

A VAP-IP benchmark derived from 45 observational (benchmark) groups of mechanically ventilated patients is 22.1%.

-

The mean VAP-IP of 35 control groups from studies of three non-antimicrobial methods of VAP prevention versus 33 control groups of studies of SDD are, respectively, within 2 percentage points of versus more than 13 percentage points higher than the benchmark.

-

By contrast, the mean VAP-IP of 35 intervention groups studies of non-antimicrobial methods versus 34 SDD intervention groups are each within six percentage points of the benchmark.

-

The paradoxical findings are most apparent in comparisons limited to the highest quality studies.

-

These observations cannot readily be accounted for with adjustments for group level factors such as proportion of trauma admissions, mode of diagnosis and study quality.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- MV:

-

mechanical ventilation

- SDD:

-

selective digestive decontamination

- SE:

-

standard error

- VAP:

-

Ventilator associated pneumonia

- VAP-IP:

-

VAP-Incidence proportion.

References

George DL: Epidemiology of nosocomial ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1993, 14: 163-169. 10.1086/646705

Cook DJ, Kollef MH: Risk factors for ICU-acquired pneumonia. JAMA 1998, 279: 1605-1606. 10.1001/jama.279.20.1605

Chastre J, Fagon JY: Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165: 867-903.

Bergmans DCJJ, Bonten MJM: Nosocomial pneumonia. In Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. 3rd edition. Edited by: Mayhall CG. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:311-339.

Safdar N, Dezfulian C, Collard HR, Saint S: Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 2184-2193. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000181731.53912.D9

Liberati A, D'Amico R, Pifferi S, Torri V, Brazzi L, Parmelli E: Antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce respiratory tract infections and mortality in adults receiving intensive care (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009, CD000022.

Messori A, Trippoli S, Vaiani M, Gorini M, Corrado A: Bleeding and pneumonia in intensive care patients given ranitidine and sucralfate for prevention of stress ulcer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2000, 321: 1103-1106. 10.1136/bmj.321.7269.1103

Subirana M, Solà I, Benito S: Closed tracheal suction systems versus open tracheal suction systems for mechanically ventilated adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007, CD004581.

Siempos II, Vardakas KZ, Kopterides P, Falagas ME: Impact of passive humidification on clinical outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 2843-2851. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000295302.67973.9A

Stoutenbeek CP, van Saene HK, Miranda DR, Zandstra DF: The effect of selective decontamination of the digestive tract on colonisation and infection rate in multiple trauma patients. Intensive Care Med 1984, 10: 185-192. 10.1007/BF00259435

de Smet AMGA, Kluytmans JAJW, Cooper BS, Mascini EM, Benus RFJ, van der Werf TS, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P, Bogaers-Hofman D, van der Meer NJ, Bernards AT, Kuijper EJ, Joore JC, Leverstein-van Hall MA, Bindels AJ, Jansz AR, Wesselink RM, de Jongh BM, Dennesen PJ, van Asselt GJ, te Velde LF, Frenay IH, Kaasjager K, Bosch FH, van Iterson M, Thijsen SF, Kluge GH, Pauw W, de Vries JW, Kaan JA, et al.: Decontamination of the digestive tract and oropharynx in ICU patients. NEJM 2009, 360: 20-31. 10.1056/NEJMoa0800394

Hurley JC: Profound effect of study design factors on ventilator-associated pneumonia incidence of prevention studies: benchmarking the literature experience. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008, 61: 1154-1161. 10.1093/jac/dkn086

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ: A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2009, 172: 137-159. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x

Spiegelhalter DJ: Handling over-dispersion of performance indicators. Qual Saf Health Care 2005, 14: 347-351. 10.1136/qshc.2005.013755

Agresti A: Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd edition. Hoboken: Wiley Interscience; 2002.

Greenland S, O'Rourke K: Meta-analysis. In Modern Epidemiology. 3rd edition. Edited by: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2008:652-682.

Harris RJ, Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Harbord RM, Altmamn DG, Sterne JA: Metan: fixed and random effects-meta-analysis. Stata J 2008, 8: 3-28.

Harbord RM, Higgins JP: Meta-regression in Stata. Stata J 2008, 8: 493-519.

Akca O, Koltka K, Uzel S, Cakar N, Pembeci K, Sayan MA, Tutuncu AS, Karakas SE, Calangu S, Ozkan T, Esen F, Telci L, Sessler DI, Akpir K: Risk factors for early-onset, ventilator-associated pneumonia in critical care patients: selected multiresistant versus nonresistant bacteria. Anesthesiology 2000, 93: 638-645. 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00011

Apostolopoulou E, Bakakos P, Katostaras T, Gregorakos L: Incidence and risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in 4 multidisciplinary intensive care units in Athens, Greece. Respir Care 2003, 48: 681-688.

Baker AM, Meredith JW, Haponik EF: Pneumonia in intubated trauma patients. Microbiology and outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 153: 343-349.

Baraibar J, Correa H, Mariscal D, Gallego M, Valles J, Rello J: Risk factors for infection by Acinetobacter baumannii in intubated patients with nosocomial pneumonia. Chest 1997, 112: 1050-1054. 10.1378/chest.112.4.1050

Beck-Sague CM, Sinkowitz RL, Chinn RY, Vargo J, Kaler W, Jarvis WR: Risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in surgical intensive-care-unit patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996, 17: 374-376. 10.1086/647323

Bercault N, Boulain T: Mortality rate attributable to ventilator-associated nosocomial pneumonia in an adult intensive care unit: a prospective case-control study. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 2303-2309. 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00012

Bochicchio GV, Joshi M, Bochicchio K, Shih D, Meyer W, Scalea TM: A time-dependent analysis of intensive care unit pneumonia in trauma patients. J Trauma 2004, 56: 296-301. 10.1097/01.TA.0000109857.22312.DF

Bonten MJ, Gaillard CA, van Tiel FH, Smeets HG, van der Geest S, Stobberingh EE: The stomach is not a source for colonization of the upper respiratory tract and pneumonia in ICU patients. Chest 1994, 105: 878-884. 10.1378/chest.105.3.878

Braun SR, Levin AB, Clark KL: Role of corticosteroids in the development of pneumonia in mechanically ventilated head-trauma victims. Crit Care Med 1986, 14: 198-201. 10.1097/00003246-198603000-00006

Craven DE, Kunches LM, Kilinsky V, Lichtenberg DA, Make BJ, McCabe WR: Risk factors for pneumonia and fatality in patients receiving continuous mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986, 133: 792-796.

Daschner F, Kappstein I, Schuster F, Scholz R, Bauer E, Joossens D, Just H: Influence of disposable ('Conchapak') and reusable humidifying systems on the incidence of ventilation pneumonia. J Hosp Infect 1988, 11: 161-168. 10.1016/0195-6701(88)90059-X

Daumal F, Colpart E, Manoury B, Mariani M, Daumal M: Changing heat and moisture exchangers every 48 hours does not increase the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999, 20: 347-349. 10.1086/501631

de Latorre FJ, Pont T, Ferrer A, Rossello J, Palomar M, Planas M: Pattern of tracheal colonization during mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 152: 1028-1033.

Eggimann P, Hugonnet S, Sax H, Touveneau S, Chevrolet JC, Pittet D: Ventilator-associated pneumonia: caveats for benchmarking. Intensive Care Med 2003, 29: 2086-2089. 10.1007/s00134-003-1991-9

Elatrous S, Boukef R, Ouanes Besbes L, Marghli S, Nooman S, Nouira S, Abroug F: Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: agreement between quantitative cultures of endotracheal aspiration and plugged telescoping catheter. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 853-858. 10.1007/s00134-004-2270-0

Fagon JY, Chastre J, Domart Y, Trouillet JL, Pierre J, Darne C, Gibert C: Nosocomial pneumonia in patients receiving continuous mechanical ventilation. Prospective analysis of 52 episodes with use of a protected specimen brush and quantitative culture techniques. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989, 139: 877-884.

Fagon JY, Chastre J, Vuagnat A, Trouillet JL, Novara A, Gibert C: Nosocomial pneumonia and mortality among patients in intensive care units. JAMA 1996, 275: 866-869. 10.1001/jama.275.11.866

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Chevret S, Arlet G, Marie O, Rouveau M, Popoff N, Schlemmer B: Oropharyngeal or gastric colonization and nosocomial pneumonia in adult intensive care unit patients. A prospective study based on genomic DNA analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997, 156: 1647-1656.

Ibrahim EH, Ward S, Sherman G, Kollef MH: A comparative analysis of patients with early-onset vs late-onset nosocomial pneumonia in the ICU setting. Chest 2000, 117: 1434-1442. 10.1378/chest.117.5.1434

Ibrahim EH, Tracy L, Hill C, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH: The occurrence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a community hospital: risk factors and clinical outcomes. Chest 2001, 120: 555-561. 10.1378/chest.120.2.555

Jacobs S, Chang RW, Lee B, Bartlett FW: Continuous enteral feeding: a major cause of pneumonia among ventilated intensive care unit patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1990, 14: 353-356. 10.1177/0148607190014004353

Jimenez P, Torres A, Rodriguez-Roisin R, de la Bellacasa JP, Aznar R, Gatell JM, Agusti-Vidal A: Incidence and etiology of pneumonia acquired during mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 1989, 17: 882-885. 10.1097/00003246-198909000-00007

Kanafani ZA, Kara L, Hayek S, Kanj SS: Ventilator-associated pneumonia at a tertiary-care center in a developing country: incidence, microbiology, and susceptibility patterns of isolated microorganisms. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003, 24: 864-869. 10.1086/502151

Kappstein I, Schulgen G, Beyer U, Geiger K, Schumacher M, Daschner FD: Prolongation of hospital stay and extra costs due to ventilator-associated pneumonia in an intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1992, 11: 504-508. 10.1007/BF01960804

Kingston GW, Phang PT, Leathley MJ: Increased incidence of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients with subclinical aspiration. Am J Surg 1991, 161: 589-592. 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90906-T

Kollef MH: Ventilator-associated pneumonia. A multivariate analysis. JAMA 1993, 270: 1965-1970. 10.1001/jama.270.16.1965

Kollef MH, Silver P, Murphy DM, Trovillion E: The effect of late-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia in determining patient mortality. Chest 1995, 108: 1655-1662. 10.1378/chest.108.6.1655

Kollef MH, Von Harz B, Prentice D, Shapiro SD, Silver P, St John R, Trovillion E: Patient transport from intensive care increases the risk of developing ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 1997, 112: 765-773. 10.1378/chest.112.3.765

Langer M, Mosconi P, Cigada M, Mandelli M: Long-term respiratory support and risk of pneumonia in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Unit Group of Infection Control. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989, 140: 302-305.

Mauritz W, Graninger W, Schindler I, Karner J, Zadrobilek E, Sporn P: [Pathogenic flora in the gastric juice and bronchial secretion of long-term ventilated intensive-care patients]. Anaesthesist 1985, 34: 203-207.

Memish ZA, Cunningham G, Oni GA, Djazmati W: The incidence and risk factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a Riyadh hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000, 21: 271-273. 10.1086/501758

Moine P, Timsit JF, De Lassence A, Troche G, Fosse JP, Alberti C, Cohen Y: Mortality associated with late-onset pneumonia in the intensive care unit: results of a multi-center cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2002, 28: 154-163. 10.1007/s00134-001-1172-7

Papazian L, Bregeon F, Thirion X, Gregoire R, Saux P, Denis JP, Perin G, Charrel J, Dumon JF, Affray JP, Gouin F: Effect of ventilator-associated pneumonia on mortality and morbidity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 154: 91-97.

Rashkin MC, Davis T: Acute complications of endotracheal intubation. Relationship to reintubation, route, urgency, and duration. Chest 1986, 89: 165-167. 10.1378/chest.89.2.165

Rello J, Quintana E, Ausina V, Castella J, Luquin M, Net A, Prats G: Incidence, etiology, and outcome of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. Chest 1991, 100: 439-444. 10.1378/chest.100.2.439

Rello J, Ausina V, Ricart M, Puzo C, Net A, Prats G: Nosocomial respiratory tract infections in multiple trauma patients. Influence of level of consciousness with implications for therapy. Chest 1992, 102: 525-529. 10.1378/chest.102.2.525

Rello J, Ausina V, Ricart M, Puzo C, Quintana E, Net A, Prats G: Risk factors for infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 1994, 20: 193-198. 10.1007/BF01704699

Rello J, Sonora R, Jubert P, Artigas A, Rue M, Valles J: Pneumonia in intubated patients: role of respiratory airway. Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 154: 111-115.

Rodriguez JL, Gibbons KJ, Bitzer LG, Dechert RE, Steinberg SM, Flint LM: Pneumonia: incidence, risk factors, and outcome in injured patients. J Trauma 1991, 31: 907-912. 10.1097/00005373-199107000-00005

Ruiz-Santana S, Garcia Jimenez A, Esteban A, Guerra L, Alvarez B, Corcia S, Gudin J, Martinez A, Quintana E, Armengol S, et al.: ICU pneumonias: a multi-institutional study. Crit Care Med 1987, 15: 930-932. 10.1097/00003246-198710000-00007

Salata RA, Lederman MM, Shlaes DM, Jacobs MR, Eckstein E, Tweardy D, Toossi Z, Chmielewski R, Marino J, King CH, et al.: Diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia in intubated, intensive care unit patients. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987, 135: 426-432.

Sofianou DC, Constandinidis TC, Yannacou M, Anastasiou H, Sofianos E: Analysis of risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000, 19: 460-463. 10.1007/s100960000236

Tejada Artigas A, Bello Dronda S, Chacon Valles E, Munoz Marco J, Villuendas Uson MC, Figueras P, Suarez FJ, Hernandez A: Risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia in critically ill trauma patients. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 304-309. 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00015

Timsit JF, Chevret S, Valcke J, Misset B, Renaud B, Goldstein FW, Vaury P, Carlet J: Mortality of nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated patients: influence of diagnostic tools. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 154: 116-123.

Torres A, Aznar R, Gatell JM, Jimenez P, Gonzalez J, Ferrer A, Celis R, Rodriguez-Roisin R: Incidence, risk, and prognosis factors of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990, 142: 523-528.

Adams DH, Hughes M, Elliott TS: Microbial colonization of closed-system suction catheters used in liver transplant patients. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1997, 13: 72-76. 10.1016/S0964-3397(97)80135-8

Ben-Menachem T, Fogel R, Patel RV, Touchette M, Zarowitz BJ, Hadzijahic N, Divine G, Verter J, Bresalier RS: Prophylaxis for stress-related gastric hemorrhage in the medical intensive care unit. A randomized, controlled, single-blind study. Ann Intern Med 1994, 121: 568-575.

Boots RJ, George N, Faoagali JL, Druery J, Dean K, Heller RF: Double-heater-wire circuits and heat-and-moisture exchangers and the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 687-693. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201887.51076.31

Boots RJ, Howe S, George N, Harris FM, Faoagali J: Clinical utility of hygroscopic heat and moisture exchangers in intensive care patients. Crit Care Med 1997, 25: 1707-1712. 10.1097/00003246-199710000-00021

Branson RD, Davis K Jr, Brown R: Comparison of three humidification techniques during mechanical ventilation: Patient selection, cost, and infection considerations. Respir Care 1996, 41: 809-816.

Combes P, Fauvage B, Oleyer C: Nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients, a prospective randomised evaluation of the Stericath closed suctioning system. Intensive Care Med 2000, 26: 878-882. 10.1007/s001340051276

Conrad SA, Gabrielli A, Margolis B, Quartin A, Hata JS, Frank WO, Bagin RG, Rock JA, Hepburn B, Laine L: Randomized, double-blind comparison of immediate-release omeprazole oral suspension versus intravenous cimetidine for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 760-765. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000157751.92249.32

Cook D, Guyatt G, Marshall J, Leasa D, Fuller H, Hall R, Peters S, Rutledge F, Griffith L, McLellan A, et al.: A comparison of sucralfate and ranitidine for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med 1998, 338: 791-797. 10.1056/NEJM199803193381203

Deppe SA, Kelly JW, Thoi LL, Chudy JH, Longfield RN, Ducey JP, Truwit CL, Antopol MR: Incidence of colonization, nosocomial pneumonia, and mortality in critically ill patients using a Trach Care closed-suction system versus an open-suction system: prospective, randomized study. Crit Care Med 1990, 18: 1389-1393. 10.1097/00003246-199012000-00016

Dreyfuss D, Djedaini K, Gros I, Mier L, Le Bourdelles G, Cohen Y, Estagnasie P, Coste F, Boussougant Y: Mechanical ventilation with heated humidifiers or heat and moisture exchangers: effects on patient colonization and incidence of nosocomial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 151: 986-992.

Eddleston JM, Vohra A, Scott P, Tooth JA, Pearson RC, McCloy RF, Morton AK, Doran BH: A comparison of the frequency of stress ulceration and secondary pneumonia in sucralfate- or ranitidine-treated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med 1991, 19: 1491-1496. 10.1097/00003246-199112000-00009

Eddleston JM, Pearson RC, Holland J, Tooth JA, Vohra A, Doran BH: Prospective endoscopic study of stress erosions and ulcers in critically ill adult patients treated with either sucralfate or placebo. Crit Care Med 1994, 22: 1949-1954.

Hanisch EW, Encke A, Naujoks F, Windolf J: A randomized, double-blind trial for stress ulcer prophylaxis shows no evidence of increased pneumonia. Am J Surg 1998, 176: 453-457. 10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00239-6

Hurni JM, Feihl F, Lazor R, Leuenberger P, Perret C: Safety of combined heat and moisture exchanger filters in long-term mechanical ventilation. Chest 1997, 111: 686-691. 10.1378/chest.111.3.686

Johnson KL, Kearney PA, Johnson SB, Niblett JB, MacMillan NL, McClain RE: Closed versus open endotracheal suctioning: costs and physiologic consequences. Crit Care Med 1994, 22: 658-666. 10.1097/00003246-199404000-00023

Kirton OC, DeHaven B, Morgan J, Morejon O, Civetta J: A prospective, randomized comparison of an in-line heat moisture exchange filter and heated wire humidifiers: rates of ventilator-associated early-onset (community-acquired) or late-onset (hospital-acquired) pneumonia and incidence of endotracheal tube occlusion. Chest 1997, 112: 1055-1059. 10.1378/chest.112.4.1055

Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Boyd V, Silver P, Von Harz B, Trovillion E, Prentice D: A randomized clinical trial comparing an extended-use hygroscopic condenser humidifier with heated-water humidification in mechanically ventilated patients. Chest 1998, 113: 759-767. 10.1378/chest.113.3.759

Lacherade JC, Auburtin M, Cerf C, Van de Louw A, Soufir L, Rebufat Y, Rezaiguia S, Ricard JD, Lellouche F, Brun-Buisson C, et al.: Impact of humidification systems on ventilator-associated pneumonia: a randomized multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 172: 1276-1282. 10.1164/rccm.200408-1028OC

Laggner AN, Lenz K, Base W, Druml W, Schneeweiss B, Grimm G: Prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in long-term ventilated patients. Sucralfate versus ranitidine. Am J Med 1989, 86: 81-84. 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90164-2

Lorente L, Lecuona M, Martin MM, Garcia C, Mora ML, Sierra A: Ventilator-associated pneumonia using a closed versus an open tracheal suction system. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 115-119. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000150267.40396.90

Lorente L, Lecuona M, Jimenez A, Mora ML, Sierra A: Tracheal suction by closed system without daily change versus open system. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 538-544. 10.1007/s00134-005-0057-6

Lorente L, Lecuona M, Jimenez A, Mora ML, Sierra A: Ventilator-associated pneumonia using a heated humidifier or a heat and moisture exchanger: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN88724583]. Crit Care 2006, 10: R116. 10.1186/cc5009

Martin C, Perrin G, Gevaudan MJ, Saux P, Gouin F: Heat and moisture exchangers and vaporizing humidifiers in the intensive care unit. Chest 1990, 97: 144-149. 10.1378/chest.97.1.144

Memish ZA, Oni GA, Djazmati W, Cunningham G, Mah MW: A randomized clinical trial to compare the effects of a heat and moisture exchanger with a heated humidifying system on the occurrence rate of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Infect Control 2001, 29: 301-305. 10.1067/mic.2001.115404

Metz CA, Livingston DH, Smith JS, Larson GM, Wilson TH: Impact of multiple risk factors and ranitidine prophylaxis on the development of stress-related upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial. The Ranitidine Head Injury Study Group. Crit Care Med 1993, 21: 1844-1849. 10.1097/00003246-199312000-00010

Mustafa NA, Akturk G, Ozen I, Koksal I, Erciyes N, Solak M: Acute stress bleeding prophylaxis with sucralfate versus ranitidine and incidence of secondary pneumonia in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 1995, 21: 287. 10.1007/BF01701491

O'Keefe GE, Gentilello LM, Maier RV: Incidence of infectious complications associated with the use of histamine2-receptor antagonists in critically ill trauma patients. Ann Surg 1998, 227: 120-125.

Pickworth KK, Falcone RE, Hoogeboom JE, Santanello SA: Occurrence of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated trauma patients: a comparison of sucralfate and ranitidine. Crit Care Med 1993, 21: 1856-1862. 10.1097/00003246-199312000-00012

Prod'hom G, Leuenberger P, Koerfer J, Blum A, Chiolero R, Schaller MD, Perret C, Spinnler O, Blondel J, Siegrist H, et al.: Nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients receiving antacid, ranitidine, or sucralfate as prophylaxis for stress ulcer. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1994, 120: 653-662.

Rabitsch W, Kostler WJ, Fiebiger W, Dielacher C, Losert H, Sherif C, Staudinger T, Seper E, Koller W, Daxbock F, et al.: Closed suctioning system reduces cross-contamination between bronchial system and gastric juices. Anesth Analg 2004, 99: 886-892.

Roustan JP, Kienlen J, Aubas P, Aubas S, du Cailar J: Comparison of hydrophobic heat and moisture exchangers with heated humidifier during prolonged mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 1992, 18: 97-100. 10.1007/BF01705040

Thomason MH, Payseur ES, Hakenewerth AM, Norton HJ, Mehta B, Reeves TR, Moore-Swartz MW, Robbins PI: Nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated trauma patients during stress ulcer prophylaxis with sucralfate, antacid, and ranitidine. J Trauma 1996, 41: 503-508. 10.1097/00005373-199609000-00020

Topeli A, Harmanci A, Cetinkaya Y, Akdeniz S, Unal S: Comparison of the effect of closed versus open endotracheal suction systems on the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Hosp Infect 2004, 58: 14-19. 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.05.005

Welte T, Ziesing S, Schulte S, Wagner TO: Incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia in mechnaically ventilated pateints: a comparison of closed versus open endotracheal suctioning [abstract]. Eur Respir J 1997, 10: 319.

Zeitoun SS, de Barros AL, Diccini S: A prospective, randomized study of ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients using a closed vs. open suction system. J Clin Nurs 2003, 12: 484-489. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00749.x

Abele-Horn M, Dauber A, Bauernfeind A, Russwurm W, Seyfarth-Metzger I, Gleich P, Ruckdeschel G: Decrease in nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated patients by selective oropharyngeal decontamination (SOD). Intensive Care Med 1997, 23: 187-195. 10.1007/s001340050314

Aerdts SJ, van Dalen R, Clasener HA, Festen J, van Lier HJ, Vollaard EJ: Antibiotic prophylaxis of respiratory tract infection in mechanically ventilated patients. A prospective, blinded, randomized trial of the effect of a novel regimen. Chest 1991, 100: 783-791. 10.1378/chest.100.3.783

Bergmans DC, Bonten MJ, Gaillard CA, Paling JC, van der Geest S, van Tiel FH, Beysens AJ, de Leeuw PW, Stobberingh EE: Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia by oral decontamination: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164: 382-388.

Blair P, Rowlands BJ, Lowry K, Webb H, Armstrong P, Smilie J: Selective decontamination of the digestive tract: a stratified, randomized, prospective study in a mixed intensive care unit. Surgery 1991, 110: 303-309.

Boland JP, Sadler DL, Stewart W, Wood DJ, Zerick W, Snodgrass KR: Reduction of nosocomial respiratory tract infections in the multiple trauma patients requiring mechanical ventilation by selective parenteral and enteral antisepsis regimen (SPEAR) in the intensive care. In XVII International Congress of Chemotherapy: 1991. Berlin; 1991.

Brun-Buisson C, Legrand P, Rauss A, Richard C, Montravers F, Besbes M, Meakins JL, Soussy CJ, Lemaire F: Intestinal decontamination for control of nosocomial multiresistant gram-negative bacilli. Study of an outbreak in an intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med 1989, 110: 873-881.

Camus C, Bellissant E, Sebille V, Perrotin D, Garo B, Legras A, Renault A, Le Corre P, Donnio PY, Gacouin A, et al.: Prevention of acquired infections in intubated patients with the combination of two decontamination regimens. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 307-314. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000152224.01949.01

Cockerill FR, Muller SR, Anhalt JP, Marsh HM, Farnell MB, Mucha P, Gillespie DJ, Ilstrup DM, Larson-Keller JJ, Thompson RL: Prevention of infection in critically ill patients by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. Ann Intern Med 1992, 117: 545-553.

Ferrer M, Torres A, Gonzalez J, Puig de la Bellacasa J, el-Ebiary M, Roca M, Gatell JM, Rodriguez-Roisin R: Utility of selective digestive decontamination in mechanically ventilated patients. Ann Intern Med 1994, 120: 389-395.

Finch RG, Tomlinson P, Holliday M, Sole K, Stack KC, Rocker G: Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) in the prevention of secondary sepsis in a medical/surgical intensive care unit [abstract]. Seventeenth international congress of chemotherapy, Berlin; 1991:0471.

Gastinne H, Wolff M, Delatour F, Faurisson F, Chevret S: A controlled trial in intensive care units of selective decontamination of the digestive tract with nonabsorbable antibiotics. The French Study Group on Selective Decontamination of the Digestive Tract. N Engl J Med 1992, 326: 594-599. 10.1056/NEJM199202273260903

Georges B, Mazerolles M, Decun JF, Rouge P, Pomies S, Cougot P: Décontamination digestive sélective résultats d'une étude chez le polytraumatisé. Réanimation Soins Intensifs Médecin d'Urgence 1994, 3: 621-627.

Hammond JM, Potgieter PD, Saunders GL, Forder AA: Double-blind study of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in intensive care. Lancet 1992, 340: 5-9. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92422-C

Jacobs S, Foweraker JE, Roberts SE: Effectiveness of selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) in an ICU with a policy encouraging a low gastric pH. Clin Intens Care 1992, 3: 52-58.

Kerver AJ, Rommes JH, Mevissen-Verhage EA, Hulstaert PF, Vos A, Verhoef J, Wittebol P: Prevention of colonization and infection in critically ill patients: a prospective randomized study. Crit Care Med 1988, 16: 1087-1093. 10.1097/00003246-198811000-00001

Korinek AM, Laisne MJ, Nicolas MH, Raskine L, Deroin V, Sanson-Lepors MJ: Selective decontamination of the digestive tract in neurosurgical intensive care unit patients: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Crit Care Med 1993, 21: 1466-1473. 10.1097/00003246-199310000-00013

Krueger WA, Lenhart FP, Neeser G, Ruckdeschel G, Schreckhase H, Eissner HJ, Forst H, Eckart J, Peter K, Unertl KE: Influence of combined intravenous and topical antibiotic prophylaxis on the incidence of infections, organ dysfunctions, and mortality in critically ill surgical patients: a prospective, stratified, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166: 1029-1037. 10.1164/rccm.2105141

Laggner AN, Tryba M, Georgopoulos A, Lenz K, Grimm G, Graninger W, Schneeweiss B, Druml W: Oropharyngeal decontamination with gentamicin for long-term ventilated patients on stress ulcer prophylaxis with sucralfate? Wien Klin Wochenschr 1994, 106: 15-19.

Lingnau W, Berger J, Javorsky F, Fille M, Allerberger F, Benzer H: Changing bacterial ecology during a five-year period of selective intestinal decontamination. J Hosp Infect 1998, 39: 195-206. 10.1016/S0195-6701(98)90258-4

Palomar M, Alvarez-Lerma F, Jorda R, Bermejo B, Catalan Study Group of Nosocomial Pneumonia Prevention: Prevention of nosocomial infection in mechanically ventilated patients: selective digestive decontamination versus sucralfate. Clin Intens Care 1997, 8: 228-235. 10.1080/714029035

Pneumatikos I, Koulouras V, Nathanail C, Goe D, Nakos G: Selective decontamination of subglottic area in mechanically ventilated patients with multiple Trauma. Intensive Care Med 2002, 28: 432-437. 10.1007/s00134-002-1238-1

Pugin J, Auckenthaler R, Lew DP, Suter PM: Oropharyngeal decontamination decreases incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. JAMA 1991, 265: 2704-2710. 10.1001/jama.265.20.2704

Quinio B, Albanese J, Bues-Charbit M, Viviand X, Martin C: Selective decontamination of the digestive tract in multiple trauma patients. A prospective double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Chest 1996, 109: 765-772. 10.1378/chest.109.3.765

Rocha LA, Martin MJ, Pita S, Paz J, Seco C, Margusino L, Villanueva R, Duran MT: Prevention of nosocomial infection in critically ill patients by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Intensive Care Med 1992, 18: 398-404. 10.1007/BF01694341

Rodriguez-Roldan JM, Altuna-Cuesta A, Lopez A, Carrillo A, Garcia J, Leon J, Martinez-Pellus AJ: Prevention of nosocomial lung infection in ventilated patients: use of an antimicrobial pharyngeal nonabsorbable paste. Crit Care Med 1990, 18: 1239-1242. 10.1097/00003246-199011000-00011

Sanchez Garcia M, Cambronero Galache JA, Lopez Diaz J, Cerda Cerda E, Rubio Blasco J, Gomez Aguinaga MA, Nunez Reiz A, Rogero Marin S, Onoro Canaveral JJ, Sacristan del Castillo JA: Effectiveness and cost of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in critically ill intubated patients. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 158: 908-916.

Stoutenbeek CP, van Saene HKF, Zandstra DF: Prevention of multiple organ failure by selective decontamination of the digestive tract in multiple trauma patients. In The Immune Consequences of Shock, Trauma and Sepsis. Volume 2. Edited by: Faist E, Baue AE, Schildberg FW. Lengerich: Pabst Science; 1996:1055-1066.

Stoutenbeek CP, van Saene HK, Miranda DR, Zandstra DF: The effect of selective decontamination of the digestive tract on mortality in multiple trauma patients: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 261-270. 10.1007/s00134-006-0455-4

Ulrich C, Harinck-de Weerd JE, Bakker NC, Jacz K, Doornbos L, de Ridder VA: Selective decontamination of the digestive tract with norfloxacin in the prevention of ICU-acquired infections: a prospective randomized study. Intensive Care Med 1989, 15: 424-431. 10.1007/BF00255597

Unertl K, Ruckdeschel G, Selbmann HK, Jensen U, Forst H, Lenhart FP, Peter K: Prevention of colonization and respiratory infections in long-term ventilated patients by local antimicrobial prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med 1987, 13: 106-113. 10.1007/BF00254795

Verwaest C, Verhaegen J, Ferdinande P, Schetz M, Van den Berghe G, Verbist L, Lauwers P: Randomized, controlled trial of selective digestive decontamination in 600 mechanically ventilated patients in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1997, 25: 63-71. 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00014

Wiener J, Itokazu G, Nathan C, Kabins SA, Weinstein RA: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of selective digestive decontamination in a medical-surgical intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis 1995, 20: 861-867.

Winter R, Humphreys H, Pick A, MacGowan AP, Willatts SM, Speller DC: A controlled trial of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in intensive care and its effect on nosocomial infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 1992, 30: 73-87. 10.1093/jac/30.1.73

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327: 557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Iezzoni LI: The risks of risk adjustment. JAMA 1997, 278: 1600-1607. 10.1001/jama.278.19.1600

Hurley JC: Prophylaxis with enteral antibiotics in ventilated patients: selective decontamination or selective cross-infection? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1995, 39: 941-947.

Morris AC, Kefala K, Simpson AJ, Wilkinson TS, Everingham K, Kerslake D, Raby S, Laurenson IF, Swann DG, Walsh TS: Evaluation of the effect of diagnostic methodology on the reported incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Thorax 2009, 64: 516-522. 10.1136/thx.2008.110239

Delaney A, Gray H, Laupland KB, Zuege DJ: Kinetic bed therapy to prevent nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2006, 10: R70. 10.1186/cc4912

Chlebicki MP, Safdar N: Topical chlorhexidine for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 595-602. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253395.70708.AC

Hurley JC: Individual patient data meta-analysis in intensive care medicine and contextual effects. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 903-904. 10.1007/s00134-010-1812-x

Cook DJ, Walter SD, Cook RJ, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH, Leasa D, Jaeschke RZ, Brun-Buisson C, for the Canadian Critical Care Trails Group: Incidence of and risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Ann Intern Med 1998, 129: 433-440.

Hurley JC: Inapparent outbreaks of ventilator-associated pneumonia: an ecologic analysis of prevention and cohort studies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005, 26: 374-390. 10.1086/502555

Ebner W, Kropec-Hubner A, Daschner FD: Bacterial resistance and overgrowth due to selective decontamination of the digestive tract. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000, 19: 243-247. 10.1007/s100960050470

Saunders GL, Hammond JM, Potgieter PD, Plumb HA, Forder AA: Microbiological surveillance during selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD). J Antimicrob Chemother 1994, 34: 529-544. 10.1093/jac/34.4.529

Merrer J, Santoli F, Appere de Vecchi C, Tran B, De Jonghe B, Outin H: "Colonization pressure" and risk of acquisition of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a medical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000, 21: 718-723. 10.1086/501721

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JH produced the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2010_8691_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional file 2: VAP-IP data for component groups of studies of non-antibiotic methods of VAP prevention. (DOC 132 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hurley, J.C. Paradoxical ventilator associated pneumonia incidences among selective digestive decontamination studies versus other studies of mechanically ventilated patients: benchmarking the evidence base. Crit Care 15, R7 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9406

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9406