Abstract

Introduction

Delirium is the most common neurological complication following cardiac surgery. Much research has focused on potential causes of delirium; however, the sequelae of delirium have not been well investigated. The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between delirium and sepsis post coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and to determine if delirium is a predictor of sepsis.

Methods

Peri-operative data were collected prospectively on all patients. Subjects were identified as having agitated delirium if they experienced a short-term mental disturbance marked by confusion, illusions and cerebral excitement. Patient characteristics were compared between those who became delirious and those who did not. The primary outcome of interest was post-operative sepsis. The association of delirium with sepsis was assessed by logistic regression, adjusting for differences in age, acuity, and co-morbidities.

Results

Among 14,301 patients, 981 became delirious and 227 developed sepsis post-operatively. Rates of delirium increased over the years of the study from 4.8 to 8.0% (P = 0.0003). A total of 70 patients of the 227 with sepsis, were delirious. In 30.8% of patients delirium preceded the development of overt sepsis by at least 48 hours. Multivariate analysis identified several factors associated with sepsis, (receiver operating characteristic (ROC) 79.3%): delirium (odds ratio (OR) 2.3, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.6 to 3.4), emergent surgery (OR 3.3, CI 2.2 to 5.1), age (OR 1.2, CI 1.0 to 1.3), pre-operative length of stay (LOS) more than seven days (OR 1.6, CI 1.1 to 2.3), pre-operative renal insufficiency (OR 1.9, CI 1.2 to 2.9) and complex coronary disease (OR 3.1, CI 1.8 to 5.3).

Conclusions

These data demonstrate an association between delirium and post-operative sepsis in the CABG population. Delirium emerged as an independent predictor of sepsis, along with traditional risk factors including age, pre-operative renal failure and peripheral vascular disease. Given the advancing age and increasing rates of delirium in the CABG population, the prevention and management of delirium need to be addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac surgery is increasingly being performed on older patients with limited physiologic reserve and multiple medical co-morbidities [1]. A significant number of patients, especially the elderly, develop peri-operative neurological complications ranging from subtle cognitive dysfunction and mild confusion to frank delirium, and occasionally permanent stroke. The prevalence of delirium after cardiac surgery has been reported to be as low as 3%, and as high as 72% [2–4].

The importance of delirium is frequently dismissed, as it is seen as a transient entity. It is, however, the most common neurological complication after cardiac surgery [5]. Multiple pre-operative predictors of delirium have been uncovered including advanced age, previous stroke, and various medications [5]. Post-operative delirium can be very difficult to manage once it has occurred. The efficacy of delirium treatment strategies published thus far are at best modest [6].

Delirium after cardiac surgery has been shown to increase hospital and ICU stay, and may even be life threatening [5]. Furthermore, long-term survival and quality of life have been shown to be adversely effected in those who suffer peri-operative delirium [7]. However, there are many other outcomes of interest that have not been investigated as they relate to delirium. In particular, while it is known that delirium is a common sign of end organ dysfunction in sepsis, there is no published literature examining the relationship between delirium preceding infectious complications, including sternal wound infection, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis. As delirious patients are difficult to properly care for and frequently exhibit behaviors that may predispose them to infection such as not following sternal precautions, failing to clear secretions, and requiring catheters for long periods, the authors suspect that delirious patients may be more likely to develop sepsis. The objective of this study therefore was to determine if preceding delirium is associated with sepsis following CABG surgery, or simply a consequence.

Materials and methods

Patient population

This study included all patients undergoing isolated CABG surgery at the Queen Elizabeth II (QEII) Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and in two cardiac centers in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada between June 1998 and July 2007. The QEII Health Sciences Centre is the sole cardiac surgical center in the province of Nova Scotia as well as parts of surrounding provinces. The Health Sciences Center and St. Boniface General Hospital are the only cardiac surgical centers serving the province of Manitoba.

Data collection and variable selection

The Maritime Heart Center Cardiac Surgery Registry and the Manitoba Cardiac Surgery Database are detailed clinical databases that prospectively capture pre-, intra-, and post-operative information on all cardiac surgery patients. The Manitoba Heart Database captures data from both centers in the province that conduct heart surgery. The two databases include cases from the same time period and were created using the same Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) data definitions, allowing them to be concatenated. Delirium was defined as per the STS definition as, "mental disturbance marked by illness, confusion, cerebral excitement, and having a comparatively short course" [8].

Preoperative characteristics included age, sex, smoking history, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), pre-operative length of stay (LOS), recent myocardial infarction (MI) (occurring within 21 days prior to surgery), pre-operative renal insufficiency (RF, Cr >176 μmol/L), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD), ejection fraction (EF) <40%, urgency (emergent surgery defined as occurring in the next available operating time; these patients have ongoing, cardiac compromise and are unresponsive to any therapy except cardiac surgery) and redo cardiac surgery. The primary outcome of interest was sepsis. Sepsis was defined as "post-operative clinical syndrome of sepsis, with positive blood cultures" [8]. Additionally, we included 22 patients as septic who clinically met the criteria for Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) but who did not have positive blood cultures, but either (a) had these cultures drawn after the initiation of antibiotics, and/or (b) had other positive cultures (sputum, sternum, urine). In septic patients who did not have positive blood cultures, the onset of sepsis was determined by the timing of the first diagnosis of sepsis or SIRS in physician charting. Patients were screened for sepsis over the entire course of their hospitalization.

A retrospective review of the charts of all septic patients were undertaken to determine the time between onset of delirium and sepsis. Patients were considered to be delirious first only if delirium preceded sepsis by a minimum of 48 hours, with no clinical signs of sepsis between the onset of delirium and time of drawing of blood culture. Other data collected on chart review included identification of microbe grown in the blood cultures of the septic patients.

Full ethics approval was obtained from all three institutional research ethics boards, in keeping with the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. A waiver of informed consent was granted by all three research ethics boards as the study did not involve therapeutic interventions or potential risks to the involved subjects.

Statistical analysis

All analysis was done on the combined group of patients from the two databases. Prior to concatenating the databases, rates of delirium and sepsis were compared between the two using chi-squared tests to ensure they were comparable. Univariate comparisons of pre-operative characteristics between delirious and non-delirious patients, and between patients who developed sepsis and those who did not, were conducted using χ2 tests or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables.

The association between delirium (defined as delirium that preceded sepsis by at least 48 hours) and sepsis was assessed by logistic regression after adjusting for relevant risk factors. Clinical variables with univariate chi-square P < 0.20 were presented to the model; by backward elimination only variables significant at P ≤ 0.05 were retained. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated as a measure of sensitivity and specificity for the logistic regression model. A bootstrap procedure was performed on 200 subsamples to confirm the independent predictors of sepsis; furthermore, the 95% confidence interval of the ROC was obtained from the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

The authors had full access to the data and take full responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

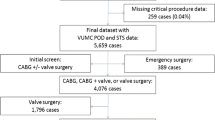

Between June 1998 and July 2007, a total of 14,301 patients underwent isolated CABG surgery at the QEII Health Sciences Centre and the two Winnipeg centers. Thirty-nine patients were eliminated from the analysis due to missing data. Of the remaining 14,262 patients, 981 (6.9%) developed delirium, and 227 patients (1.6%) developed sepsis. Of the septic patients, 70 also had delirium, 34 of whom clearly developed delirium between 2 and 10 days prior to the onset of sepsis (Figure 1). Rates of delirium and sepsis were compared between the two provinces. Rates of sepsis were higher in Nova Scotia than Manitoba (2.32% versus 0.85%, P < 0.001), but rates of delirium were equivalent (P = 0.32), as were rates of delirium in the septic patients (P = 0.06).

Those patients that developed post-operative delirium were more likely to have diabetes, renal insufficiency, COPD, PVD or CVD, and pre-operative atrial fibrillation (all P < 0.0001) (Table 1). Furthermore, they were more likely to have undergone a redo or emergent procedure (P < 0.0001). The patients who became delirious were more likely to develop pneumonia, urinary tract infections, deep sternal wound infections, and sepsis (all P < 0.0001) (Table 2). In addition, patients who became septic had a greater pre-operative length of stay than those who did not (Table 3). In those patients who did become septic, the mean time between their operation and diagnosis of sepsis was 10.52 days (standard deviation (SD) 13.97 days). The mean length of stay in ICU prior to the diagnosis of sepsis was 3.53 days (SD 8.16 days). However, not all patients were in ICU at the time of development of their delirium or sepsis.

Septic patients had higher rates of diabetes, CVD, renal insufficiency and COPD (all P < 0.0001). In addition, they were older, more likely to be delirious, and more likely to have stayed in hospital for more than seven days prior to undergoing surgery (all P < 0.0001).

The causative organism was identified in the large majority of septic patients (Table 4). Over half of the patients grew Staphylococci, with two cases of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. More than two causative organisms were identified in 8.8% of patients. No organism was identified in 9.7% of patients.

A multivariate analysis was performed with a focus on patients who were deemed delirious for more than 48 hours prior to a diagnosis of sepsis. In these patients, delirium was significantly associated with post-operative sepsis with an OR of 2.32 (95% CI 1.59 to 3.39) after adjusting for pre-operative prognostic variables (Table 5). Other variables associated with sepsis included the pre-morbid conditions of elevated BMI, CHF, PVD/CVD, renal insufficiency, and atrial fibrillation (all P < 0.05). Emergent surgery, redo operation, and a pre-operative in-hospital stay of more than seven days were also associated with sepsis. The ROC for the sepsis model was 77.2%, 95% CI 76.6 to 82.5.

Discussion

This represents the largest analysis of delirium in the cardiac surgical population published to date. In this study of over 14,000 isolated CABG patients, we have confirmed that delirium is prevalent post-operatively, and have found evidence to suggest an association between delirium and sepsis.

It has been widely recognized that delirium can be a symptom of end organ dysfunction in sepsis. However, this is the first analysis to suggest that delirium may in fact play a role in the development of sepsis. Importantly, in this study cohort, delirium was found to precede the overt diagnosis of sepsis in 30.8% of patients, thus suggesting that delirium may put patients at increased risk of developing sepsis.

Delirium is common in the general ICU population with an estimated prevalence of up to 62% [9] and common in the post-operative cardiac surgical population [5]. There have been many models developed to predict its development. In the general ICU population, delirium has been associated with prolonged ventilation times, self-extubation, and re-intubation [10]. Prolonged mechanical ventilation, as well as an increased number of airway procedures, are known to increase the risk of nosocomial pneumonia and the subsequent development of sepsis [11]. Delirium has also been associated with removal of catheters, resulting in increased instrumentation of the urinary tract and increased risk of the development of urinary tract infections [12]. Furthermore, there is a pharmacological armamentarium used to treat delirium, including anticholinergic medications that have side effects including decreased secretions and urinary retention, and a number of sedating agents that decrease the amount of time patients are likely to spend ambulatory and may impact their ability for self-care.

Delirious patients have been shown to have poor oral intake and are at increased risk of developing malnutrition [13]. Malnutrition significantly impairs immune function, putting the patient at increased risk of peri-operative infectious complications [14]. Furthermore, delirious patients experience a loss of day-night orientation, have significant disruption to regular sleep patterns and are frequently sleep deprived [15]. A number of immunological functions are dependent on circadian rhythms and regular sleep, and those who are sleep deprived are therefore less able to mount an appropriate immune response to pathogens [16].

Patients with delirium often have prolonged intubation times [5], are less likely to comply with sternal precautions, require prolonged bladder catheterization, and are less likely to mobilize [12, 17]. Furthermore, owing to poor nutrition [18], disruption to their sleep-wake cycle [15], and disruptions in their natural defenses [19], patients with delirium may be more prone to develop sepsis with any given infection. In lieu of these features, we hypothesized that delirium may precede infectious complications, and sepsis.

A number of other findings in our study warrant mention. In particular, pre-operative atrial fibrillation was found to be associated with delirium and sepsis, both univariately and in the multivariate analysis. This is likely due to the fact that atrial fibrillation is indicative of global physiologic impairment, rather than being causative of either entity [20].

Despite our attempts to clearly delineate a timeline between the onset of delirium and sepsis, there remains the possibility that delirium may in fact be an early marker of sepsis rather than a predictor. Allowing that to be the case, the findings of this study can still be considered to be of merit: at the very least, perhaps delirium should be thought of as a prompt to expeditiously investigate for sepsis.

There are several limitations that should be noted. This is a three centre, retrospective study with the inherent bias and confounding in such studies. Furthermore, our analysis was limited by the STS definition of delirium, which is strictly that of an agitated delirium. As such, it is likely that a significant number of patients with hypoactive delirium or sub-syndromal delirium were not classified as delirious in this study. There was not an a priori protocol for delirium management at any of the study sites; each institution treated delirious patients as per the discretion of the attending physician. Both of these issues could be addressed in quality improvement projects which: (1) identify delirious patients based on a more inclusive definition, (2) provide protocol driven interventions to reduce rates of delirium (3) institute guidelines to more efficaciously treat those who become delirious (4) actively investigate delirious patient for signs of infection, perhaps even drawing blood cultures at the time of initial signs of delirium. A strength of this study was the individual chart reviews conducted on each of the septic patients, through which time lines were clearly delineated. Furthermore, this study included a very large cohort of patients.

It has previously been established in non-cardiac surgical and intensive care populations that delirium is associated with an increased risk for in-hospital morbidity, and poorer long-term outcomes. We have identified another adverse outcome associated with delirium: sepsis. Given the advancing age and increased medical co-morbidities of patients putting them at increased risk of developing in-hospital delirium, along with the increased focus on improving post-operative outcomes, attention must be paid to preventing and managing delirium. Those at risk need to be identified early, and those who become delirious must be appropriately managed which should include active surveillance for infectious complications.

Conclusions

Delirium is strongly associated with sepsis, and through this study has been demonstrated to frequently precede the development of sepsis. The development of delirium in post-operative patients needs to be taken seriously and treated aggressively.

Key messages

-

Delirium is common after cardiac surgery.

-

Delirium is associated with sepsis, and importantly has now been shown to precede sepsis in some cases.

-

Delirious patients should be closely monitored for the development of other post-operative co-morbidities.

-

Delirium is not a benign or self-limiting process.

Authors' information

BJM is an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) Clinical Fellow at the University of Calgary. KJB is the senior statistical analyst for the division of Cardiac Surgery at Dalhousie University. RCA is the Rudy Falk Clinician-Scientist and Assistant Professor in Surgery and Physiology at the University of Manitoba. RJFB is an assistantociate professor of surgery at Dalhousie University.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CABG:

-

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CHF:

-

congestive heart failure

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CVD:

-

cerebrovascular disease

- EF:

-

ejection fraction

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- MI:

-

myocardial infarction

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PVD:

-

Peripheral Vascular Disease

- RF:

-

renal failure

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- SIRS:

-

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

- STS:

-

Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

References

Djaiani G: Aortic arch atheroma: stroke reduction in cardiac surgical patients. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2006, 10: 143-157. 10.1177/1089253206289006

Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones RH, Mark DB, Reves JG, Blumenthal JA, The Neurological Outcome Research G the Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology Research Endeavors I: Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2001, 344: 395-402. 10.1056/NEJM200102083440601

Roach GW, Kanchuger M, Mangano CM, Newman M, Nussmeier N, Wolman R, Aggarwal A, Marschall K, Graham SH, Ley C, Ozanne G, Mangano DT, Herskowitz A, Katseva V, Sears R, The Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research G the Ischemia R Education Foundation I: Adverse cerebral outcomes after coronary bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 1996, 335: 1857-1864. 10.1056/NEJM199612193352501

Nussmeier N: Neuropsychiatric complications of cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 1994, 8: 13-18. 10.1016/1053-0770(94)90611-4

Sockalingam S, Parekh N, Bogoch II, Sun J, Mahtani R, Beach C, Bollegalla N, Turzanski S, Seto E, Kim J, Dulay P, Scarrow S, Bhalerao S: Delirium in the postoperative cardiac patient: a review. Journal of Cardiac Surgery 2005, 20: 560-567. 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2005.00134.x

Prakanrattana U, Prapaitrakool S: Efficacy of risperidone for prevention of postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care 2007, 35: 714-719.

Loponen P, Luther M, Wistbacka JO, Nissinen J, Sintonen H, Huhtala H, Tarkka MR: Postoperative delirium and health related quality of life after coronary artery bypass grafting. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal 2008, 42: 337-344. 10.1080/14017430801939217

Society of Thoracic Surgeons[http://www.sts.org]

McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK: Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2003, 51: 591-598. 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00201.x

Morandi A, Jackson JC, Wesley Ely E: Delirium in the intensive care unit. International Review of Psychiatry 2009, 21: 43-58. 10.1080/09540260802675296

Palmer LB: Ventilator-associated infection. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2009, 15: 230-235. 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283292650

Inouye SK, Charpentier PA: Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons: predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA 1996, 275: 852-857. 10.1001/jama.275.11.852

Olofsson B, Stenvall M, Lundstrõm M, Svensson O, Gustafson Y: Malnutrition in hip fracture patients: an intervention study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2007, 16: 2027-2038. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01864.x

Hulsewe KW, van Acker BA, von Meyenfeldt MF, Soeters PB: Nutritional depletion and dietary manipulation: effects on the immune response. World Journal of Surgery 1999, 23: 536-544. 10.1007/PL00012344

Figueroa-Ramos MI, Arroyo-Novoa CM, Lee KA, Padilla G, Puntillo KA: Sleep and delirium in ICU patients: a review of mechanisms and manifestations. Intensive Care Medicine 2009, 35: 781-795. 10.1007/s00134-009-1397-4

Habbal OA, Al-Jabri AA: Circadian rhythm and the immune response: a review. International Reviews of Immunology 2009, 28: 93-108. 10.1080/08830180802645050

Ganai S, Lee KF, Merrill A, Lee MH, Bellantonio S, Brennan M, Lindenauer P: Adverse outcomes of geriatric patients undergoing abdominal surgery who are at high risk for delirium. Arch Surg 2007, 142: 1072-1078. 10.1001/archsurg.142.11.1072

Voyer P, Richard S, Doucet L, Carmichael PH: Predisposing factors associated with delirium among demented long-term care residents. Clin Nurs Res 2009, 18: 153-171. 10.1177/1054773809333434

DeKeyser F: Psychoneuroimmunology in critically ill patients. AACN Clinical Issues 2003, 14: 25-32. 10.1097/00044067-200302000-00004

Bilato C, Corti MC, Baggio G, Rampazo D, Cutolo A, Iliceto S, Crepaldi G: Prevalence, functional impact, and mortality of atrial fibrillation in an older italian populatio (from the pro.v.a. study). American Journal of Cardiology 2009, 104: 1092-1097. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.058

Acknowledgements

We thank the research associates in Cardiac Sciences at St. Boniface Hospital in Winnipeg: Brenda Zahara, Rachel Gerstein, and Kim Wiebe are members of the Cardiovascular Health Research in Manitoba (CHaRM) Investigator Group and the Manitoba Cardiac Sciences Program. Earlier versions of this data in abstract form were presented at the Canadian Cardiovascular Congress 2008, Toronto, ON, 25-29 October 2008, and at the Society for Critical Care Medicine Meeting 2009, Nashville, TN, 2-5 February 2009.

This study was not funded. BJM is an AHFMR funded clinical fellow and also receives funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). KJB is funded by the Division of Cardiac Surgery and the Department of Surgery Dalhousie University. RCA is funded by St. Boniface General Hospital Research Foundation, Manitoba Health Research Council, Manitoba Medical Service Foundation and the CIHR. No funding bodies played any role in the study, manuscript preparation or submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BJM designed the study, conducted the chart review, assisted with statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. KJB performed the statistical analysis and aided in revisions of the manuscript. RJFB and RCA contributed equally in achieving institutional ethics approval and co-senior authors on this study.

Rakesh C Arora and Roger JF Baskett contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, BJ., Buth, K.J., Arora, R.C. et al. Delirium as a predictor of sepsis in post-coronary artery bypass grafting patients: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care 14, R171 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9273

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9273