Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this research is to provide recommendations for the management of glycemic control in critically ill patients.

Methods

Twenty-one experts issued recommendations related to one of the five pre-defined categories (glucose target, hypoglycemia, carbohydrate intake, monitoring of glycemia, algorithms and protocols), that were scored on a scale to obtain a strong or weak agreement. The GRADE (Grade of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system was used, with a strong recommendation indicating a clear advantage for an intervention and a weak recommendation indicating that the balance between desirable and undesirable effects of an intervention is not clearly defined.

Results

A glucose target of less than 10 mmol/L is strongly suggested, using intravenous insulin following a standard protocol, when spontaneous food intake is not possible. Definition of the severe hypoglycemia threshold of 2.2 mmol/L is recommended, regardless of the clinical signs. A general, unique amount of glucose (enteral/parenteral) to administer for any patient cannot be suggested. Glucose measurements should be performed on arterial rather than venous or capillary samples, using central lab or blood gas analysers rather than point-of-care glucose readers.

Conclusions

Thirty recommendations were obtained with a strong (21) and a weak (9) agreement. Among them, only 15 were graded with a high level of quality of evidence, underlying the necessity to continue clinical studies in order to improve the risk-to-benefit ratio of glucose control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Critically ill patients in intensive care units (ICUs) develop insulin resistance that is responsible for so-called "stress diabetes" [1–3]. For a long time this was accepted insofar as stress diabetes was seen as an adaptive metabolic response. However, over the last 10 years, there have been changes in clinical practice resulting from a better knowledge of glucose toxicity and from observations on the benefits of glucose control in clinical trials [4]. Since the first trial in Leuven in 2001 [4], a plethora of articles has been published on the subject but these have triggered much controversy and confused the clinician, with the result that clinical practice varies widely. For this reason, the French Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care (Société Française d'Anesthésie-Réanimation, SFAR) and the French-speaking Society for Intensive Care (Société de Réanimation de Langue Française, SRLF) decided to develop expert panel consensus recommendations. Published in 2008 [5], these were updated in May 2009 after the publication of the NICE-SUGAR trial [6]. This paper addresses the practical aspects of glucose control in ICUs, the diagnosis and risks of hypoglycemia, and how to monitor glucose levels in ICU patients.

Materials and methods

A steering committee, comprising a chair, two SFAR members, and two SRLF members, was set up in late 2007. This committee chose the topics to be addressed and nominated the experts in charge of each specific area. The choice of experts was validated by both societies; 21 French, Belgian and Swiss experts, as well as several medical societies with a stake in the chosen topic, accepted to participate in the development of the recommendations. No member of the committee from industry was present at any of the meetings.

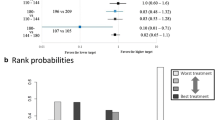

The global process for elaborating recommendations is summarised in Additional file 1, Table S1. The aim of the first meeting was to explain the methodology of the working group. Based on a MEDLINE search, each subgroup of experts in charge of its topic had to produce a review including the analysis of the literature and the arguments to propose recommendations. A first version of recommendations was elaborated using the GRADE method (Grade of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [7, 8]. This method takes into account the quality of evidence, the balance between benefits versus harms, endpoint relevance, and costs. As explained during the first meeting, the quality of evidence of each recommendation was systematically specified by the subgroups (Additional file 1, Table S2). The global evidence quality was therefore up- or downgraded by weighting for these three extra factors. Each recommendation was thus allocated a final level of evidence which determined its wording: (i) we recommend (or we do not recommend) for a strong recommendation, (ii) we strongly suggest (or we strongly do not suggest) for a moderate recommendation (iii) we suggest (or we do not suggest) for a weak recommendation (Additional file 1, Table S2). Each recommendation was then rated by all experts on a scale from 1 to 9 (1 = disagreement, 9 = agreement). A median score was calculated (after exclusion of the highest or lowest rating, if necessary) that could fall into one of three zones: (1 to 3) = disagreement; (4 to 6) = indecision; (7 to 9) = agreement. If the confidence interval of the median was within the first or last zone, the strength of the recommendation was considered to be weak or strong, respectively (Figure 1). With this methodology, we must distinguish the strength of recommendation and the level of agreement (or disagreement) obtained from the vote of the experts; for example, it is possible to propose a weak recommendation with a strong agreement. Recommendations for which agreement was not reached in a first round were reworded in order to obtain a better consensus. Up to three rounds were needed to reach an agreement for all recommendations.

Process for determination of strong versus weak agreement. Each expert rated the recommendations on a scale from 1 to 9. A median score ± confidence interval was then calculated based on all expert votes (if necessary, one isolated higher or lower value was excluded). A median score between 1 and 3 indicated disagreement; a median score between 4 and 6 indicated indecision; a median score between 7 and 9 agreement. If the confidence interval was within or without the previous defined zones, the strength of agreement (or disagreement) was considered to be strong or weak, respectively.

Excluding the specific problems of diabetic patients and children, five items were analysed including: i) the glycemic target in ICUs; ii) the diagnosis and consequences of hypoglycemia in ICUs; iii) the rules for carbohydrate intake; iv) the glucose monitoring; and v) the impact of algorithms and protocols. Recommendations are summarized in Additional file 1, Table S3.

Results

Glucose target in ICUs

We strongly suggest avoidance of severe hyperglycemia (> 10 mmol/L/180 mg/dL) in adult ICU patients. We suggest keeping glucose levels under control although a universally acceptable upper limit cannot be specified (strong agreement).

We suggest avoidance of tight glucose control in an emergency situation as this management seems to not be reasonable and is potentially dangerous (strong agreement).

We also strongly suggest avoidance of large variations in glucose levels in ICUs (strong agreement).

We do not recommend using any drug other than intravenous insulin for glucose control in ICUs (weak agreement).

Hypoglycemia: diagnosis and harms

We suggest that in ICU patients, the glucose threshold is probably <2.2 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) for severe hypoglycemia (strong agreement).

In ICU patients unable to express themselves, we recommend that hypoglycemia be corrected even in the absence of clinical signs (strong agreement).

We suggest that severe hypoglycemia is probably associated with an increased risk of mortality although no causal relationship has been established (weak agreement).

Implementation of published strategies for tight glucose control exposes patients to more frequent and long-lasting severe hypoglycemia (strong agreement).

Long-lasting severe hypoglycemia can induce irreversible brain lesions. We suggest that neurological lesions following hypoglycemia might be partly related to excess glucose infusion (strong agreement).

In a strategy of tight glucose control, we recommend closely monitoring glucose blood levels for the early detection of severe hypoglycemia (strong agreement).

We recommend favoring arterial or venous blood samples rather than capillary samples in ICU patients with suspected hypoglycemia as capillary samples often overestimate glucose (strong agreement).

Carbohydrate intake

We suggest reducing hyperglycemia by restricting intravenous glucose in critically ill patients (weak agreement).

We suggest interrupting intravenous insulin infusion by an electric syringe pump when the patient has resumed food intake and to continue glucose monitoring for at least three preprandial controls (strong agreement).

We cannot suggest a general recommendation of maximal and minimal amounts of intravenous and/or enteral carbohydrates be administered to critically ill patients, regardless of the type, the severity of pathology and of the delay from onset of disease (strong agreement).

We suggest that glucose intake should not be prohibited in critically ill patients provided that glycemia is under control (weak agreement).

We suggest that compliance with the glucose target might be improved by continuous adaptation of enteral nutrition and insulin infusion rates (weak agreement).

Glucose monitoring

We recommend performing glucose measurements in the laboratory; this remains the current gold standard technique (strong agreement).

We recommend performing glucose measurements in the following preferential order of sampling: arterial, venous, capillary (strong agreement).

As total blood and plasma glucose measurements differ, we recommend knowing the specifications of the device used (not all devices apply an automatic correction factor) (strong agreement).

Owing to endogenous and exogenous physicochemical interference, we recommend being aware of the precise specifications of the device and paper-strips that are used (strong agreement).

Algorithms and protocols

We recommend defining and implementing a standard protocol for glucose control in each medical team (strong agreement).

Among available glucose control protocols, none may be considered superior to any other (weak agreement).

We recommend including in a glucose control protocol, at the very least, recommendations on the use of rapid action insulin as a continuous infusion by electric syringe pump, as well as on correction and monitoring procedures for episodes of hypoglycemia (strong agreement).

We strongly suggest giving preference to a route of administration providing a constant intravenous insulin infusion rate (strong agreement).

We recommend no longer using static glucose control protocols which determine insulin delivery rate on the basis of the last glucose measurement (strong agreement).

When using glucose control protocols, we strongly suggest taking into account carbohydrate intake in the determination of the insulin delivery rate (strong agreement).

We suggest using a computer-assisted glucose control protocol when there are more than two entries and outputs (weak agreement).

We strongly suggest that the efficacy of a glucose control protocol depends on all of the following criteria: training time, glucose control performance, risk of hypoglycemia, mean error rate, nursing workload (weak agreement).

We suggest assessing the efficacy of a glucose control protocol by considering preferably the following variables: percent time in- and above-target, hyperglycemia index, and variability (weak agreement).

We recommend taking into account the increase in staff workload when implementing a tight glucose control protocol. We recommend allocating time to train the staff before implementing the protocol (strong agreement).

Discussion

Glucose target in ICUs

The deleterious impact of hyperglycemia in ICU patients has long been overlooked. However, many observational studies have confirmed that there is a link between hyperglycemia and increased mortality in critically ill patients [9–13]. The decrease in mortality reported in the 2001 Leuven trial after intensive insulin therapy [4] led to a considerable change in clinical practice, with hyperglycemia in ICU patients becoming less acceptable. This trial was a single-center prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) which compared tight glucose control by intensive insulin therapy (IIT) (4.4 to 6.1 mmol/L) to conventional glucose management (10 to 12.1 mmol/L) in surgical ICU patients. IIT was associated with a decrease in ICU mortality from 8.0 to 4.6% and hospital mortality from 10.9 to 7.2%. The beneficial effects of IIT were greater in patients who spent more than five days in an ICU. A decrease in ICU morbidity was also observed, including lower incidence of systemic infections, acute renal insufficiency, anemia, polyneuropathy, duration of artificial ventilation, and length of stay in the ICU.

However, since the 2001 Leuven trial, the results of several RCTs have dampened the enthusiasm generated by these early results [14–19]. Van den Berghe et al. performed the same study in ICU medical patients, with the same objectives and same method, and detected no significant difference in mortality between groups [15]. Two other single-center studies found no decrease in mortality and morbidity in medical and surgical ICU patients receiving IIT [17, 18]. Three multicenter RCTs have been performed. The VISEP (Volume substitution and Insulin therapy in severe sepsis) trial assessed the impact of tight glucose control in patients with septic shock or severe sepsis [16]. The 28-day and 90-day mortality rates did not differ between the intensive insulin therapy group (24.7% and 39.7%, respectively) and the conventional treatment group (26% and 35.4%, respectively). Nor did they differ in the GLUCONTROL trial performed in 1,078 medical and surgical ICU patients [19]. The NICE-SUGAR trial in 6,022 ICU patients reported a higher 90-day mortality rate in the tight glucose control group (4.5 to 6 mmol/L) than in the conventional treatment group (< 10 mmol/L) (27.6 vs 24.9%, P = 0.02) [14]. Glucose control in ICU patients was found to be beneficial in terms of mortality and morbidity in the oldest meta-analysis [20] but was without effect in the two most recent meta-analyses, even after inclusion of the NICE-SUGAR trial results [21–23].

All these studies are difficult to interpret and to compare because of differences in patient populations and protocol (glucose target levels and measurement methods, carbohydrate intake), and because of methodological weaknesses: single-center studies [4, 15, 17, 18], surgical and/or medical patient populations [4, 15, 16], early study discontinuation [16, 19], and difficulty in reaching the target glucose level [14, 16, 19]. Currently, it is not possible to establish a universal glucose threshold that might provoke toxicity in ICU patients, irrespective of their disease and environment.

There is no evidence for a benefit of tight glucose control in an emergency situation. Even if hyperglycemia on patient admission to hospital is a marker of a poor prognosis in acute cerebral and cardiovascular disease [24–27], no study so far has shown a short-term benefit of tight glucose control in such emergencies [28–32]. The absence of benefit is largely outweighed by a potentially highly harmful increase in the risk of hypoglycemia.

Several studies have confirmed that acute glucose variations are an independent predictive factor of mortality [13, 33–35]. The greater the variations and the closer the mean glucose level to normal, the higher the mortality (the effect is less marked if mean glucose is high >150 mg/dL) [32]. These harmful effects could be related to endothelial dysfunction and increased oxidative stress, although not reported in critically ill patients.

No study has assessed different methods of hyperglycemia management in ICUs. The need for optimal efficacy (reaching target values and minimizing variations) and for maximum safety (reducing the incidence of hypoglycemia) is nevertheless a strong argument in favor of continuous intravenous insulin infusion by an electric syringe pump. In ICU patients with edema or vasomotor variations, intravenous infusion minimized fluctuations in insulin absorption and enabled delivery to be adapted fast and effectively to variations in glucose levels [36, 37]. By adjusting insulin delivery rate in advance, it might be possible to prevent hyperglycemia induced by glucose intake (food) or drugs (glucocorticoids), but no study addressed this question in critically ill patients. Subcutaneous insulin absorption is unreliable and may be unpredictable in patients with edema or shock; glucose control occurs haphazardly [38]. In a perioperative study in diabetic patients, target values were reached in only 40% of patients after subcutaneous insulin [36].

Hypoglycemia: diagnosis and harms

The definitions of hypoglycemia and its severity are well established for diabetic patients [39, 40]. A third party has to be present to confirm the degree of severity before oral or intravenous glucose may be administered. However, there are no published data or definitions for hypoglycemia in ICU patients. Unlike in diabetic patients, it is arbitrarily and exclusively defined on the basis of a biological threshold without taking any account of neurologic signs. Most studies conducted in ICUs were not designed to assess hypoglycaemia and rely only on the definition based on the blood glucose concentration, regardless of associated clinical signs (< 2.2 mmol/L) [3, 4, 14–18, 41].

The definition of severe hypoglycemia used in diabetic patients cannot be transposed directly to ICU patients who may be unable to describe clinical signs because of spontaneous or sedation-induced consciousness disorders. Other cardiovascular clinical signs may also escape attention. The lack of a specific sign and the inability to detect early warning signs increase the risk of severe hypoglycemia [3, 19, 41]. Most cases of hypoglycemia described in ICU trials are of short duration (< 2 hours) and exclusively biology-based with no report of a clinical sign of severity [42].

In most studies, hypoglycemia is associated with a significant increase in mortality (relative risk: 2.3 to 3.8) [4, 16, 19, 43, 44]. Other studies have, however, suggested that hyperglycemia is not an independent predictive factor of mortality [45–47]. Current evidence can therefore neither refute nor establish a causal relationship. Recent data have, however, highlighted factors that predispose to hypoglycaemia such as continuous haemofiltration, diabetes, mechanical ventilation, sepsis, administration of insulin and inotropic drugs [45–47], and brain lesions [48]. In such situations, the effects of a strategy targetting a higher glucose target level should be evaluated.

Most ICU studies use at least one episode of severe hypoglycemia as a yardstick to report hypoglycemia incidence. The incidence (5 to 25% according to study) is always significantly higher than in the control group. The most recent studies report a three- to six-fold increased risk of severe hypoglycemia [20, 22, 45–55].

The available evidence related to the clinical consequences of long-lasting severe hypoglycemia and its correction is not reported from critically ill patients. In experimental models, post-hypoglycemic neuronal death is not directly due to an energy deficit but arises from a cascade of reactions triggered by hypoglycemia, in particular a glutamate and zinc influx that activates post-synaptic glutamate receptors. This leads to numerous cellular modifications (for example, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), DNA modifications and impairment of membrane permeability) resulting in neuronal apoptosis [49]. Using an experimental model for severe hypoglycemia, Suh et al. showed that neuronal death hardly occurred during hypoglycemia but was marked during glucose reperfusion [50]. Neuronal death was proportional to the hyperglycemic rebound induced by exogenous glucose reperfusion, and was induced by NADPH oxidase, responsible for ROS production. This is reminiscent of the mechanisms of cellular death during episodes of reperfusion following ischemia. Despite the lack of clinical evidence supporting these experimental data, and because of variability in glucose levels, more rigorous management of hypoglycemia (infusion of a more moderate amount of glucose and closer monitoring) could be needed to prevent an excessive hyperglycemic rebound.

The higher incidence of hypoglycemia during tight glucose control, associated with the frequent absence of clinical warning signs, calls for repeated glucose measurements. However, there is no study that can be used as a basis to recommend any given interval between measurements as a function of the equilibrium observed: from 30 minutes (in cases of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia) to 4 hours depending upon glucose level stability and study [4, 15–19].

Irrespective of measurement method, glucose levels vary according to sampling site, as recently confirmed in patients with shock or edema [51–55]. Values measured on capillary samples are overestimated compared to those measured on arterial samples [53, 54]. The discrepancy would be 30% according to the most recent data [14, 53]. However, approximate measurements for non severe hypoglycemia are not acceptable in patients with no clinical signs of severity. A control measurement should be performed on arterial or venous blood in the laboratory or using a blood gas/glucose analyzer. This approach, widely used in diabetics [40], was applied in the recent NICE-SUGAR trial [14]. There have been reports of episodes of severe hypoglycemia that have remained undetected by point-of-care capillary blood analyzers [56].

Carbohydrate intake

Hyperglycemia probably has beneficial or harmful effects depending upon the mechanism of its onset, its severity, and duration [41]. Stress diabetes is a transitory abnormality induced by acute disease (inflammation, ischemia-reperfusion) and a marker of disease severity. It is also an adaptive response for overcoming the acute metabolic changes observed in ICU patients [3, 57–59]. Faster glucose turnover and insulin resistance initially provide the amount of energy substrate (glucose) that some organs need [57, 60, 61]. Hypoxia and proinflammatory phenomena (cytokines) intensify this endogenous hyperglycemia, and vice-versa, thus creating a vicious circle. The hyperglycemia can be worsened and prolonged by the development of exogenous hyperglycemia through enteral or parenteral glucose intake or glucocorticoid administration. The glucose that was initially useful is now present in excess and becomes toxic by enhancing inflammatory responses and inducing oxidative stress [62–64]. The different outcomes in the Leuven and NICE-SUGAR trials might be partly due to differences in carbohydrate intake levels. Van den Berghe et al. administered high carbohydrate levels (200 g/day) [4]. This could have enhanced glucose toxicity. The glucotoxicity would have been reversed by intensive insulin therapy. In contrast, enteral carbohydrate administration in the NICE-SUGAR trial was restricted especially during the first two to three days [14]. Early insulin administration to induce a return to normal glucose values might have worsened the patients' conditions by preventing an adaptive response.

There is no evidence justifying either the continuation or interruption of intravenous insulin therapy once ICU patients have resumed food intake. The duration of glucose monitoring in ICUs has not been investigated in a well-designed study (except in diabetic patients). According to physiopathological data, it is reasonable to expect that patients who can eat have recovered glucose regulation with appropriate endogenous insulin secretion, in particular before meals. All RCTs have used the following regimen: intravenous or subcutaneous preprandial insulin bolus with at least one glucose measurement before each meal [4, 14, 19]. Glucose monitoring was stopped once the patient left the ICU. Some studies have recommended substituting subcutaneous for intravenous insulin before the patient leaves the ICU [65]. A retrospective study in neurosurgery patients has shown that 6 to 70% of the intravenous insulin dose, administered by the subcutaneous route, provided satisfactory glucose control with no increase in risk of hypoglycemia [66].

The recommended daily energy intake in ICU patients is about 25 kcal/kg/day [67]. It may take at least two to three days to reach this objective. If the enteral calorie intake is still too low after three days, parenteral supplementation may be used [67]. Glucose is a key energy substrate; some tissues depend totally or highly on glucose. Mean daily consumption by the brain is 100 to 150 g. The source may be exogenous or endogenous. Exogenous glucose comes from enteral or parenteral carbohydrate intake. Endogenous glucose comes mostly from hepatic or muscular neoglucogenesis and can reach 300 g/day [68]. ICU patients are insulin resistant and too much exogenous glucose increases the risk of hyperglycemia [1], in particular as maximum glucose oxidation capacity is reduced to 2 to 5 mg/kg/minute [57, 69, 70]. In such a situation, glucose infusion only partially inhibits neoglucogenesis. However, these observations apply to short periods (less than three days) in cohorts of critically ill ICU patients [71], and assessment of the impact of enteral carbohydrates on glucose metabolism remains difficult (the estimated true digestive absorption is not very reliable). On the other hand, no, or very little, exogenous glucose may hasten neoglucogenesis substrate use and muscle protein catabolism. In summary, total glucose deprivation (fasting) or a too high intake clearly have harmful effects in ICU patients. However, optimal carbohydrate intake has still to be established [67].

The impact of carbohydrate intake on glucose levels in ICU patients suggests that glucose control protocols should take account of carbohydrate intake [72]. In theory, this should achieve optimal glucose control by foreseeing variations in glucose levels (hyper- and hypoglycemia). According to several reports, the performance of glucose control software accounting for carbohydrate intake is satisfactory [73–77]. However, its benefits have yet to be demonstrated in routine clinical practice.

Glucose monitoring

The gold standard measurement is one made in the laboratory on an arterial or venous blood sample using hexokinase [78, 79]. Point-of-care glucometers use other enzymes (glucose oxidase (GO) or glucose dehydrogenase (GDH)). GO is the enzyme used in the older models. It is less stable than GDH and therefore less precise, and has more limitations. Point-of-care glucose readers must comply with strict standards (ISO 15197 in Europe) regardless of the enzyme used, that is, a deviation with respect to the gold standard of <15 mg/dL for glucose levels above 75 mg/dL and a maximum 20% deviation for higher levels [80]. Most devices meet these standards but none yields a more accurate measurement (< 10% deviation) [52, 53].

The sampling site may influence glucose measurements and be a source of discordant values. Glucometers may well comply with international standards, but they were devised to measure glucose in capillary blood from ambulatory patients. The reliability of their use in ICU patients is a matter of controversy [51, 52, 54, 55, 80]. The main sources of discrepancies are vasoconstriction, low blood flow rate, a state of shock, ischemia, or edema [54, 78, 79]. In such cases, about 15% of capillary measurements vary by >20% with respect to the gold standard [78, 81]. The discrepancies are worse in cases of hypoglycemia, thus justifying confirmation in the laboratory [54]. Measurements on arterial blood show the least variation.

As plasma is richer in water than red blood cells, glucose measurements on plasma are higher than on total blood, by about 10 to 15% [79]. The discrepancy is even greater in cases of abnormal hematocrit values. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that plasma values be converted into laboratory total blood values by applying a correction factor of 1.12. However, plasma glucose does not depend on the hematocrit value and reflects active glucose more faithfully. For this reason, and in order to avoid any errors in interpretation, the American Diabetes Association and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Scientific Division (IFCC) have urged that practice be harmonized by considering plasma glucose only, regardless of sampling site and measuring device [79]. They recommend a correction factor of 1.1 to be applied to results for total blood. Most recent devices using paper-strip blood sampling have in-built automatic correction and provide plasma values [80, 82].

Point-of-care glucose meters use different measurement methods (amperometric or colorimetric reaction, enzymatic reaction (GO or GDH), calibration on total blood or plasma, and different blood volumes) which all lead to device-specific limitations, interferences, and technical constraints [82–86]. GO systems (the oldest) are influenced by blood oxygen concentration as oxygen is involved in catalysis. GDH devices use either PQQ (pyrroloquinolone quinone) or FAD (flavine adenine dinucleotide) for catalysis. Depending upon the device, certain physicochemical factors can impair measurement accuracy. Sampling conditions and interpretation of results must therefore take the type of device into account [78]. The PaO2 value, very high or low pH values, hypothermia, and altitude can influence measurements made with GO devices [87, 88]. With the oldest GO devices (amperometric reaction), PaO2 values of <40 mmHg may overestimate glucose by about 15%. The more recent GO devices (colorimetric reaction) are more reliable over a wide PaO2 range [87]. GDH devices are not affected by the PaO2 value, but high galactose or maltose concentrations may overestimate values given by GDH PQQ devices. Cases of wrong results resulting in the death of the patient have led to banning their use in such situations [89, 90]. All GDH devices (PQQ or FAD) overestimate values in the presence of high concentrations of some substances (endogenous substances: uric acid, bilirubin, triglycerides; exogenous substances: xylose, salicylate, paracetamol, mannitol). This information is supplied in the manufacturer's instructions [78]. Many continuous glucose monitoring systems (subcutaneous or intravascular measurements) are being developed and assessed. Their reliability in ICUs has yet to be demonstrated [3]. In summary, the reliability of the results depends on the user's knowledge of the device.

Algorithms and protocols

The early results of Van den Berghe et al. led to the widespread use of continuous insulin therapy for glucose control. Hospital teams drafted protocols to promote efficacy and safety. A wide variety of algorithms have been published because the choice of criteria is vast: target glucose, insulin delivery rate, monitoring interval, management by doctors or nurses, and so on. In Van den Berghe et al.'s trial, the algorithm was implemented by a specially trained nursing staff [4]. On the other hand, in the NICE-SUGAR trial, a web-based computerised protocol with several entries was used to provide insulin delivery rates and monitoring intervals [14]. In all cases, a written protocol suited to local conditions (technical and human resources) and accepted by the care team should be implemented in order to guarantee efficacy and safety [91–93].

No prospective RCT has compared the impact of glucose control protocols on morbidity and mortality. It is difficult to assess algorithm performance because of the variety of variables used. Currently, there is no evidence for choosing one protocol rather than another.

Continuous intravenous insulin provides greater efficacy, safety, and ease of use than subcutaneous administration in ICUs [3, 41, 91, 94, 95]. It is used by virtually all ICUs and is sometimes supplemented by intravenous boli. It has the advantage of limiting wide variations in glucose; this is as important as the mean hyperglycemia value [13, 12, 34, 41]. In addition, although a causal relationship between hypoglycemia and increased mortality has not been proven, it is prudent to recommend glucose control techniques that limit these episodes as far as possible [65].

A study of 100 ICU patients has shown that the incidence of severe hypoglycemia was significantly reduced when insulin was administered by a specific rather than non specific infusion route (4% vs 22%) [96]. As for continuous catecholamine administration, this helps avoid any variations in delivery that may be induced by the injection of other drugs.

Static control algorithms determine insulin delivery rate from a single (the last) glucose measurement. Dynamic control algorithms take a wide variety of other factors into account such as the ongoing insulin delivery rate, monitoring interval, glucose intake, and so on. This accounts for protocol diversity. Available evidence shows that dynamic control is better than static control [91]. The approach used should also take account of exogenous glucose intake which may affect glucose levels [72–77]. Ideally, intake should be anticipated in order to achieve more stable glucose levels [3].

Entry variables are those that spark off recommendations whereas output variables are those that make up the recommendations. The entry invariably used is glucose value but other entries such as previous insulin delivery rate and the monitoring interval may be taken into account. The output common to all algorithms is the insulin delivery rate. Other possible outputs are recommendations concerning insulin boli, food intake, monitoring interval, hypoglycemia correction, and so on. The number of entries and outputs make non computer-assisted protocol management well-nigh impossible. The complexity of the paperwork of the NICE-SUGAR trial might explain the limited time spent in-target (40%), the low proportion of eligible patients (15%), and the short monitoring intervals increasing workload [14]. Dedicated computer software is being developed [76, 77, 97–99]. There are two types of computer-assisted second generation software using complex algorithms: (i) Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) software uses a closed-loop control that takes into account the deviations with respect to target glucose value, time in-target, and variations in level [77, 100]. The changes in insulin delivery rate are always based on past measurements; (ii) Model Predictive Control (MPC) software predicts glucose values using established models [74, 76, 98].

An effective glucose control protocol does not only consider attainment of the target glucose value but also protocol adoption time by staff, risk of hypoglycemia, and the variability and reliability of measurements [73–77, 91].

The efficacy of glucose control depends on factors that differ considerably among studies. Recent work has tried to establish the factors needed to validate protocol efficacy [101–103]. The most important seem to be hyperglycemia index and variability. The frequency and severity of hypoglycemia reflect protocol safety.

The introduction of glucose control in ICUs increases staff workload because of protocol implementation time and repeated monitoring. In a prospective single-center study, the time required was two hours per day, that is, about 20% of a nurse's working day [104]. For a protocol to be effective and safe, its feasibility should be tailored to resources; close cooperation is needed between doctors and nurses for the procedure to take account of local technical and human resources. Users must accept the protocol and training [105]. Despite these measures, failure in reaching the target glucose value has been reported in over 30% of patients [106].

Conclusions

Glucose control in ICUs should be a therapeutic objective. It is no longer possible to overlook severe hyperglycemia (> 10 mmol/L) although it is not yet possible to recommend a single glucose threshold common to all types of patients and diseases, especially as glucose control exposes patients to an increased risk of potentially harmful hypoglycemia. In addition, although mean glucose is an important therapeutic target to be achieved, recent data underscore the impact of many other factors (for example, variability in glucose levels, carbohydrate intake, presence or not of chronic hyperglycemia (diabetes). The safety and reliability of glucose monitoring techniques also need to be taken into account. Progress in the accuracy, harmonisation, and automation of these techniques is needed to enhance the efficacy and safety of glucose control, and diminish workload. There is no question of introducing tight glucose control into ICUs at all costs. However, further studies are needed to answer many unsolved questions: Which target glucose values should be used in which patients? How to monitor glucose levels? Which protocols should be used? In the meantime, each team should set up formal protocols in line with their technical and human resources.

Key messages

-

Stress-induced hyperglycemia has been found to be associated with an increased morbi-mortality in critically ill patients. Thus, an excessive hyperglycemia (> 10 mmol/L) should be avoided in adult ICU patients.

-

Due to persistent conflicting data and the increased risk of hypoglycemia, strict glycemic control cannot be a universal strategy regardless of the condition of patient and the training of the team.

-

Continuous intravenous insulin is the only strategy permitted to efficiently control glycemia while decreasing the risk of glycemic variations in critically ill patients.

-

In ICU, severe hypoglycemia (< 2.2 mmol/L) should be detected, even in the absence of warning clinical signs, using a close glycemic monitoring (repeated blood samples).

-

Blood glucose concentrations determined with bedside point-of-care glucometers provides inaccurate measurements in critically ill patients. Thus, blood glucose measures should be preferentially performed on arterial (or venous) blood samples using classical laboratory devices or blood gas/glucose analyzers, especially in the case of extreme values.

Abbreviations

- FAD:

-

flavine adenine dinucleotide

- GDH:

-

glucose dehydrogenase

- GO:

-

glucose oxidase

- GRADE:

-

Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development And Evaluation

- ICUs:

-

intensive care units

- IFCC:

-

International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Scientific Division

- IIT:

-

intensive insulin therapy

- MPC:

-

Model Predictive Control

- PID:

-

Proportional-Integral-Derivative

- PQQ:

-

pyrroloquinolone quinone

- RCTs:

-

Randomized Control Trials

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- VISEP:

-

volume substitution and insulin therapy in severe sepsis

- WHO:

-

The World Health Organisation.

References

Van den Berghe G: How does blood glucose control with insulin save lives in intensive care? J Clin Invest 2004, 114: 1187-1195.

Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS: Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest 2005, 115: 1111-1119.

Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC: Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 2009, 373: 1798-1807. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5

Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R: Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2001, 345: 1359-1367. 10.1056/NEJMoa011300

Formal recommendations by the experts: Glycemic control in intensive care unit and during anaesthesia. Société française d'anesthésie et de réanimation. Société de réanimation de langue française Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2009, 28: 410-415.

Ichai C, Cariou A, Leone M, Veber B, Barnoud D, le Groupe d'Experts: Expert's formalized recommendations. Glycemic control in ICU and during anaesthesia: useful recommendations. Ann Fr Anesth Réanim 2009, 28: 717-718.

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Harbour MC, Haugh MC, Henry D, Hill S, Jaeschke R, Leng G, Liberati A, Magrini N, Mason J, Middleton P, Mrukowicz J, O'Connell D, Oxman AD, Phillips B, Schünemann HJ, Edejer TT, Varonen H, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Zaza S, GRADE Working Group: Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004, 328: 1490. 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Fakck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group: Grade: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336: 924-926. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Umpierrez GE, Isaacs SD, Bazargan N, You X, Thaler LM, Kitabchi AE: Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002, 87: 978-982. 10.1210/jc.87.3.978

Bagshaw SM, Egi M, George C, Bellomo R, Australia New Zealand Intensive Care Society Database Management Committee: Early blood glucose control and mortality in critically ill patients in Australia. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 463-470. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318194b097

Freire AX, Bridges L, Umpierrez GE, Kuhl D, Kitabchi AE: Admission hyperglycemia and other risk factors as predictors of hospital mortality in a medical ICU population. Chest 2005, 128: 3109-3116. 10.1378/chest.128.5.3109

Rady MY, Johnson DJ, Patel BM, Larson JS, Helmers RA: Influence of individual characteristics on outcome of glycemic control in intensive care unit patients with or without diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc 2005, 80: 1558-1567. 10.4065/80.12.1558

Egi M, Bellomo R, Stachowski E, French CJ, Hart G: Variability of blood glucose concentration and short-term mortality in critically ill patients. Anesthesiology 2006, 105: 244-252. 10.1097/00000542-200608000-00006

NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, Hébert PC, Heritier S, Heyland DK, McArthur C, McDonald E, Mitchell I, Myburgh JA, Norton R, Potter J, Robinson BG, Ronco JJ: Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2009, 360: 1283-1297. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625

Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wouters PJ, Milants I, Van Wijngaerden E, Bobbaers H, Bouillon R: Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med 2006, 354: 449-461. 10.1056/NEJMoa052521

Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N, Moerer O, Gruendling M, Oppert M, Grond S, Olthorff D, Jaschinski U, John S, Rossaint R, Welte T, Schaefer M, Kern P, Kuhnt E, Kiehntopf M, Hartog C, Natanson C, Loeffler M, Reinhart K, for the German Competence Network Sepsis (SepNet): Intensive Insulin Therapy and Pentastarch Resuscitation in Severe Sepsis? N Engl J Med 2008, 358: 125-139. 10.1056/NEJMoa070716

De la Rosa GC, Donado JH, Restrepo AH, Quintero AM, González LG, Saldarriaga NE, Bedoya MT, Toro JM, Velasquez JB, Valencia JC, Arango CM, Aleman PH, Vasquez EM, Chavarriaga JC, Yepea A, Pulido W, Cadavid CA: Strict glycaemic control in patients hospitalized in a mixed medical and surgical intensive care unit: a randomized clinical trial. Crit Care 2008, 12: R120. 10.1186/cc7017

Arabi YM, Dabbagh OC, Tamin HM, Al-Shimemeri AA, Memish ZA, Haddad SH, Syed SJ, Giridhar HR, Rishu AH, Al-Daker MO, Kahoul SH, Britts RJ, Sakkijha MH: Intensive versus conventional insulin therapy: a randomized controlled trial in medical and surgical critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 3190-3197. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f21aa

Preiser JC, Devos P, Ruiz-Santana S, Mélot C, Annane D, Groeneveld J, Iapichino G, Leverve X, Nitenberg G, Singer P, Wernerman M, Joannidis M, Stecher A, Chioléro R: A prospective randomised multi-centre controlled trial on tight glucose control by intensive insulin therapy in adult intensive care units: the Glucontrol study. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1738-1748. 10.1007/s00134-009-1585-2

Pittas AG, Siegel RD, Lau J: Insulin therapy and in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2006, 30: 164-172. 10.1177/0148607106030002164

Wiener RS, Wiener DC, Larson RJ: Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults. A meta-analysis. JAMA 2008, 300: 933-944. 10.1001/jama.300.8.933

Griesdale DEG, de Souza RJ, van Dam RM, Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Malhotra A, Dhaliwal R, Henderson WR, Chittock DR, Finfer S, Talmor D: Intensive insulin therapy and mortality among critically ill patients: a meta-analysis including NICE-SUGAR study data. CMAJ 2009, 180: 821-827.

Marik PE, Preiser JC: Towards understanding tight glycemic control in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2010, 137: 544-551. 10.1378/chest.09-1737

Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Pathak P, Gerstein HC: Stress hyperglycemia and prognosis of stroke in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: a systematic review. Stroke 2001, 32: 2426-2432. 10.1161/hs1001.096194

Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Gerstein HC: Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet 2000, 355: 773-778. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)08415-9

Goldberg RJ, Kramer DG, Lessard D, Yarzebski J, Gore JM: Serum glucose levels and hospital outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction without prior diabetes: a community-wide perspective. Coron Artery Dis 2007, 18: 125-131. 10.1097/01.mca.0000236291.79306.98

Oksanen T, Sjrifvars MB, Varpula T, Kuitunen A, Pettilä V, Nurmi J, Castren MA: Strict versus moderate glucose control after resuscitation from ventricular fibrillation. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 2093-2100. 10.1007/s00134-007-0876-8

Losert H, Sterz F, Roine RO, Holzer M, Martens P, Cerchiari E: Strict normoglycaemia blood glucose levels in the therapeutic management of patients within 12 h after cardiac arrest might not be necessary. Resuscitation 2008, 76: 214-220. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.08.003

Gray CS, Hildreth AJ, Sandercock PA, O'Connell JE, Johnston DE, Cartlidge NE, Bamford JM, James OF, Alberti KGM, for the GIST trialists collaboration: Glucose-potassium-insulin infusions in the management of post-stroke hyperglycaemia: the UK glucose insulin in stroke trial (GIST-UK). Lancet Neurol 2007, 6: 397-406. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70080-7

Malmberg K, Ryden L, Wedel H, Birkeland K, Bootsma A, Dickstein K, Effendic S, Fisher M, Hamsten A, Herlitz J, Hildebrandt P, Macleod K, Laakso M, Torp-Pedersen C, Waldenström A, for the DIGAMI 2 investigators: Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI2): effects on mortality and morbidity. Eur Heart J 2005, 26: 650-661. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi199

Gandhi GY, Nuttal GA, Abel MD, Mullary CJ, Schaff HV, O'Brien PC, Johnson MG, Willimans AR, Cutshall SM, Mundy LM, Rizza RA, McMahon MM: Intensive intraoperative insulin therapy versus conventional glucose management during cardiac surgery. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007, 146: 233-243.

Walters MR, Weir CJ, Lees KR: A randomised, controlled pilot study to investigate the potential benefit of intervention with insulin in hyperglycaemic acute ischaemic stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006, 22: 116-122. 10.1159/000093239

Ali NA, O'Brien JM, Dungan K, Phillips G, Marsh CB, Lemeshow S, Connors AF, Preiser JC: Glucose variability and mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 2316-2321. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181810378

Krinsley JS: Glycemic variability: a strong independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 3008-3013. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818b38d2

Dossett LA, Cao H, Mowery NT, Dortch MJ, Morris JM, May AK: Blood glucose variability is associated with mortality in the surgical intensive care unit. Am Surg 2008, 74: 679-685.

Gonzales-Michaca L, Ahumada M, Ponce-de-Leon S: Insulin subcutaneous application vs. continuous infusion for postoperative blood glucose control in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arch Med Res 2002, 33: 48-52. 10.1016/S0188-4409(01)00354-X

Bode BW, Braithwaite SS, Steed RD, Davidson PC: Intravenous insulin infusion therapy: indications, methods, and transition to subcutaneous insulin therapy. Endocr Pract 2004, 10: 71-80.

Ariza-Andraca CR, Altamirano-Bustamante E, Frati-Munari AC, Altamirano-Bustamante P, Graef-Sanchez A: Delayed insulin absorption due to subcutaneous edema. Arch Invest Med (Mex) 1991, 22: 229-233.

Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H: Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26: 1902-1912. 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1902

Workgroup on Hypoglycemia, American Diabetes Association: Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2005, 28: 1245-1249. 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1245

Fahy BG, Sheelhy AM, Coursin DE: Glucose control in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 1769-1776. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a19ceb

Lacherade JC, Jacqueminet S: Consequences of hypoglycemia. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2009, 28: e201-208.

Krinsley JS, Grover A: Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 2262-2267. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000282073.98414.4B

Egi M, Bellomo R, Stachowski E, French CJ, Hart GK, Taori G, Hegarty C, Bailey M: Hypoglycemia and outcome in critically ill patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2010, 85: 217-222. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0394

Arabi YM, Tamim HM, Rishu AH: Hypoglycemia with intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients: predisposing factors and association with mortality. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 2536-2544. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a381ad

Vriesendorp TM, DeVries JH, van Santen S, Moeniralam HS, de Jonge E, Roos YB: Evaluation of short-term consequences of hypoglycemia in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 2714-2718. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000241155.36689.91

Vriesendorp TMS, van Santen JH, De Vries JH, de Jonge E, Rosendaal FR, Schultz MJ, Rosendaal FR, Hoekstra JB: Predisposing factors for hypoglycemia in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 96-101. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194536.89694.06

Scalea TM, Bochicchio GV, Bochicchio KM: Tight glycemic control in critically injured trauma patients. Ann Surg 2007, 246: 605-610. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a789

Suh SW, Hamby AM, Swanson RA: Hypoglycemia, brain energetics, and hypoglycemic neuronal death. Glia 2007, 55: 1280-1286. 10.1002/glia.20440

Suh SW, Gum ET, Hamby AM, Chan PH, Swanson RA: Hypoglycemic neuronal death is triggered by glucose reperfusion and activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase. J Clin Invest 2007, 117: 910-918. 10.1172/JCI30077

Desachy A, Vuagnat AC, Ghazali AD, Baudin OT, Longuet OH, Calvat SN, Gissot V: Accuracy of bedside glucometry in critically ill patients: influence of clinical characteristics and perfusion index. Mayo Clin Proc 2008, 83: 400-405. 10.4065/83.4.400

Finkielman JD, Oyen LJ, Afessa B: Agreement between bedside blood and plasma glucose measurement in the ICU setting. Chest 2005, 127: 1749-1751. 10.1378/chest.127.5.1749

Critchell CD, Savarese V, Callahan A, Aboud C, Jabbour S, Marik P: Accuracy of bedside capillary blood glucose measurements in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 2079-2084. 10.1007/s00134-007-0835-4

Kanji S, Buffie J, Hutton B, Bunting PS, Singh A, McDonald K, Fergusson D, McIntyre LA, Hebert PC: Reliability of point-of-care testing for glucose measurement in critically ill adults. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 2778-2785. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000189939.10881.60

Kulkarni A, Saxena M, Price G, O'Leary MJ, Jacques T, Myburgh JA: Analysis of blood glucose measurements using capillary and arterial blood samples in intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med 2005, 31: 142-145. 10.1007/s00134-004-2500-5

Korsatko S, Ellmerer M, Schaupp L, Mader JK, Smolle KH, Tiran B, Plank J: Hypoglycaemic coma due to falsely high point-of-care glucose measurements in an ICU-patient with peritoneal dialysis: a critical incidence report. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 571-572. 10.1007/s00134-008-1362-7

Wolfe RR, Allsop JR, Burke JF: Glucose metabolism in man: responses to intravenous glucose infusion. Metabolism 1979, 28: 210-220. 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90066-0

Meszaros K, Lang CH, Bagby GJ, Spitzer JJ: Tumor necrosis factor increases in vivo glucose utilization of macrophage-rich tissues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1987, 149: 1-6. 10.1016/0006-291X(87)91596-8

Seematter G, Chioléro R, Tappy L: Glucose metabolism in physiological situation. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2009, 28: e175-e180.

Martinez A, Chiolero R, Bollman M, Revelly JP, Berger M, Cayeux C, Tappy L: Assessment of adipose tissue metabolism by means of subcutaneous microdialysis in patients with sepsis or circulatory failure. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2003, 23: 286-292. 10.1046/j.1475-097X.2003.00512.x

Michaeli B, Berger MM, Revelly JP, Tappy L, Chioléro R: Effects of fish oil on the neuro-endocrine responses to an endotoxin challenge in healthy volunteers. Clin Nutr 2007, 26: 70-77. 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.06.001

Losser MR, Damoisel C, Payen D: Glucose metabolism in acute critical situation. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2009, 28: e181-e192.

Leverve X: Hyperglycemia and oxidative stress: complex relationships with attractive prospects. Intensive Care Med 2003, 29: 511-514.

Wellen KE, Hotamisliglil GS: Inflammation, stress and diabetes. J Clin Invest 2005, 115: 1111-1119.

Inzucchi SE: Clinical practice. Management of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting. N Engl J Med 2006, 355: 1903-1911. 10.1056/NEJMcp060094

Weant KA, Ladha A: Conversion from continuous insulin infusion to subcutaneous insulin in critically ill patients. Ann Pharmacother 2009, 43: 629-634. 10.1345/aph.1L629

Singer P, Berger MM, Van den Berghe G, Biolo G, Calder P, Forbes A, Griffiths R, Kreyman G, Leverve X, Pichard C: ESPEN Guidelines on Parenteral Nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr 2009, 28: 387-400. 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.04.024

Tappy L, Schwarz JM, Schneiter P, Cayeux C, Revelly JP, Fagerquist CK, Jéquier E, Chioléro R: Effects of isoenergetic glucose-based or lipid-based parenteral nutrition on glucose metabolism, de novo lipogenesis, and respiratory gas exchanges in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1998, 26: 860-867. 10.1097/00003246-199805000-00018

Biolo G, Grimble G, Preiser JC, Leverve X, Jolliet P, Roth E, Wernerman J, Pichard C, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Working Group on Nutrition and Metabolism: Position paper of the ESICM Working Group on Nutrition and Metabolism. Metabolis basis of nutrition in intensive care unit patients: ten critical questions. Intensive Care Med 2002, 28: 1512-1520. 10.1007/s00134-002-1512-2

Wilmer A, Van den Berghe G: Parenteral nutrition. In Cecil Textbook of Medicine. 23rd edition. Edited by: Goldmand L, Ausiello D. Pennsylvania, USA: Elsevier; 2008.

Tappy L, Chioléro R: Substrate utilization in sepsis and multiple organ failure. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: S531-S534. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000278062.28122.A4

Kalfon P, Preiser JC: Tight glucose control: should we move from intensive insulin therapy alone to modulation of insulin and nutritional inputs? Crit Care 2008, 12: 156. 10.1186/cc6915

Chase JG, Shaw G, Le Compte A, Lonergan T, Willacy M, Wong XW, Lin J, Lotz T, Lee D, Hahn C: Implementation and evaluation of the SPRINT protocol for tight glycaemic control in critically ill patients: a clinical practice change. Crit Care 2008, 12: R49. 10.1186/cc6868

Cordingley JJ, Vlasselaers D, Dormand NC, Wouters PJ, Squire SD, Chassin LJ, Wilinska ME, Morgan CJ, Hovorka R, Van den Berghe G: Intensive insulin therapy: enhanced Model Predictive Control algorithm versus standard care. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 123-128. 10.1007/s00134-008-1236-z

Wilinska ME, Chassin LJ, Hovorka R: Automated glucose control in the ICU: effect of nutritional protocol and measurement error. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2006, 1: 67-70. full_text

Pachler C, Plank J, Weinhandl H, Chassin LJ, Kulnik R, Kaufmann P, Smolle KH, Pilger E, Pieber TR, Ellmerer M, Hovorka R: Tight glycaemic control by an automated algorithm with time-variant sampling in medical ICU patients. Intensive Care Med 2008, 34: 1224-1230. 10.1007/s00134-008-1033-8

Vogelzang M, Loef BG, Regtien JG, van der Horst IC, van Assen H, Zijlstra F, Nijsten MW: Computer-assisted glucose control in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2008, 34: 1421-1427. 10.1007/s00134-008-1091-y

Dungan K, Chapman J, Braithwaithe SS, Buse J: Glucose measurement: confounding issues in setting targets for inpatients management. Diabetes Care 2007, 30: 403-409. 10.2337/dc06-1679

D'Orazio P, Burnett RW, Fogh-Andersen N, Jacobs E, Kuwa K, Külpmann WR, Larsson L, Lewenstam A, Maas AH, Mager G, Nasalski JW, Okorodudu A: Approved IFCC recommendation on reporting results for blood glucose: International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Scientific Division, Working Group on Selective Electrodes and Point-of-Care testing (IFCC-SD-SEPOCT). Clin Chem Lab Med 2006, 44: 1486-1490. 10.1515/CCLM.2006.275

Lacara T, Domagtoy C, Lickliter D, Quattrocchi K, Snipes L, Kuszaj J, Prasnikar M: Comparison of point-of-care and laboratory glucose analysis in critically ill patients. Am J Crit Care 2007, 16: 336-346.

Scott MG, Bruns DE, Boyle JC, Sacks DB: Tight glucose control in the intensive care unit: are glucose meters up to the task? Clin Chem 2009, 55: 18-20. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117291

Rao LV, Jakubiak F, Sidwell JS, Winkelman JW, Snyder ML: Accuracy evaluation of a new glucometer with automated hematocrit measurement and correction. Clin Chim Acta 2005, 356: 178-183. 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.01.027

Fahy BG, Coursin DB: Critical glucose control: the devil is in the detail. Mayo Clin Proc 2008, 83: 394-397. 10.4065/83.4.394

Price GC, Stevenson K, Walsh TS: Evaluation of a continuous glucose monitor in an unselected general intensive care population. Crit Care Resusc 2008, 10: 209-216.

Savoca R, Jaworek B, Huber AR: New "plasma referenced" POCT glucose monitoring systems-are they suitable for glucose monitoring and diagnosis of diabetes? Clin Chim Acta 2006, 372: 199-201. 10.1016/j.cca.2006.03.012

Corstjens AM, Ligtenberg JJ, van der Horst IC, Spanjersberg R, Lind JS, Tulleken JE, Meertens JH, Zijlstra JG: Accuracy and feasibility of point-of-care and continuous blood glucose analysis in critically ill ICU patients. Crit Care 2006, 10: R135. 10.1186/cc5048

Tang Z, Louie RF, Lee JH, Lee DM, Miller EE, Kost GJ: Oxygen effects on glucose meter measurements with glucose dehydrogenase- and oxidase-based test strips for point-of-care testing. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1062-1070. 10.1097/00003246-200105000-00038

Oberg D, Ostenson CG: Performance of glucose dehydrogenase and glucose oxidase-based blood glucose meters at high altitude and low temperature. Diabetes Care 2005, 28: 1261-1264. 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1261

US Food and Drug Administration: Important safety information on interference with blood glucose measurement following use of parenteral maltose/oral xylose-containing products.[http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/ucm154213.htm]

ISMP Errata re:Medication Safety Alert. Be aware of false glucose results with point-of-care testing. 2005, 10: 3. [http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20050908.asp]

Meijering S, Corstjens AM, Tulleken JE, Meertens JH, Zijlstra JG, Ligtenberg JJ: Towards a feasible algorithm for tight glycaemic control in critically ill patients: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care 2006, 10: R19. 10.1186/cc3981

Davidson PC, Steed RD, Bode BW: Glucommander: a computer-directed intravenous insulin system show to be safe, simple, and effective in 120, 618 h of operation. Diabetes Care 2005, 28: 2418-2423. 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2418

Kanji S, Singh A, Tierney M, Meggison H, McIntyre L, Hebert PC: Standardization of intravenous insulin therapy improves the efficiency and safety of blood glucose control in critically ill adults. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 804-810. 10.1007/s00134-004-2252-2

Nazer LH, Chow SL, Moghissi ES: Insulin infusion protocols for critically ill patients: a highlight of differences and similarities. Endocr Pract 2007, 13: 137-146.

Wintergerst KA, Deiss D, Buckingham B, Cantwell M, Kache S, Agarwal S, Wilson DM, Steil G: Glucose control in pediatric intensive care unit patients using an insulin-glucose algorithm. Diabetes Technol Ther 2007, 9: 211-222. 10.1089/dia.2006.0031

Lacherade JC, Jacqueminet S, Preiser JC: An overview of hypoglycemia in the critically ill. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2009, 3: 1242-1249.

Meynaar IA, Dawson L, Tangkau PL, Salm EF, Rijks L: Introduction and evaluation of a computerised insulin protocol. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 591-596. 10.1007/s00134-006-0484-z

Wong XW, Singh-Levett I, Hollingsworth LJ, Shaw GM, Hann CE, Lotz T, Lin J, Wong OS, Chase JG: A novel, model-based insulin and nutrition delivery controller for glycemic regulation in critically ill patients. Diabetes Technol Ther 2006, 8: 174-190. 10.1089/dia.2006.8.174

Bequette BW: A critical assessment of algorithms and challenges in the development of closed-loop artificial pancreas. Diabetes Technol Ther 2005, 7: 28-47. 10.1089/dia.2005.7.28

Chee F, Fernando TL, Savkin AV, van Heeden V: Expert PID control system for blood glucose control in critically ill patients. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed 2003, 7: 419-422. 10.1109/TITB.2003.821326

Eslami S, de Keizer NF, de Jonge E, Schultz MJ, Abu-Hanna A: A systematic review on quality indicators for tight glycaemic control in critically ill patients: need for an unambiguous indicator reference subset. Crit Care 2008, 12: R139. 10.1186/cc7114

Van Herpe T, De Brabanter J, Beullens M, De Moor B, Van den Berghe G: Glycemic penalty index for adequately assessing and comparing different blood glucose control algorithms. Crit Care 2008, 12: R24. 10.1186/cc6800

Van Herpe T, De Moor B, Van den Berghe G: Ingredients for adequate evaluation of blood glucose algorithms as applied to the critically ill. Crit Care 2009, 13: 102. 10.1186/cc7115

Aragon D: Evaluation of nursing work effort and perceptions about blood glucose testing in tight glycemic control. Am J Crit Care 2006, 15: 370-377.

Holzinger U, Kitzberger R, Fuhrmann V, Schenk P, Kramer L, Funk G: ICU-staff education and implementation of an insulin therapy algorithm improve blood glucose control. Intensive Care Med 2006, 31: S202. [http://www.springerlink.com/content/j33677k782n561j2/fulltext.pdf]

Lacherade JC, Jabre P, Bastuji-Garin S, Grimaldi D, Fangio P, Theron V, Outin D, De Jonghe B: Failure to achieve glycemic control despite intensive insulin therapy in a medical ICU: incidence and influence on ICU mortality. Intensive Care Med 2007, 33: 814-821. 10.1007/s00134-007-0543-0

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the SFAR and SRLF for supporting this study. Their funding source only serves for logistic support, and was not involved in the elaboration of recommendations, nor was the source involved in the writing of the manuscript. The authors thank the Working Group of Metabolism and Nutrition of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine for the review and endorsement of the manuscript. This study was developed in partnership with the Association de Langue Française pour l'Etude du Diabète et des Maladies Métaboliques (ALFEDIAM), Association des Anesthésistes-Réanimateurs Pédiatres d'Expression Française (ADARPEF), Groupe d'Expression Française des Réanimateurs et Urgentistes Pédiatres (GEFRUP), Société Belge d'Anesthésie-Réanimation (SBAR), Société Francophone de Nutrition Clinique et Métabolisme (SFNEP), and Société de Réanimation Belge Intensive Zorgen (SIZ).

Experts Group: Djillali Annane (CHU Raymond Poincaré, Service de Réanimation Médicale, 104 Bd Raymond Poincaré, 92380 Garches, France), Adrien Bouglé (CHU Raymond Poincaré, Service de Réanimation Médicale, 104 Bd Raymond Poincaré, 92380 Garches, France), René Chioléro (Service de Médecine Intensive Adulte, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, 46 Rue du Bugnon, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland), Charles Damoisel (Hôpital Lariboisière, Pôle Urgence, 2 rue Ambroise Paré, 75010 Paris, France), Philippe Devos (Department of General Intensive Care, University Hospital Centre, Domaine universitaire du Sart-Tilman, 4000 Liege, Belgium), Jan Gunst (Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Catholic University of Leuven, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium), Serge Halimi (Service d'Endocrinologie Diabétologie, Hôpital A. Michallon, Bd de la Chantourne, 38700 La Tronche, France), Sophie Jacqueminet (Service de Diabétologie, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié Salpétrière, 47-83 Bd de l'hôpital, 75651 Paris cedex 13, France), Pierre Kalfon (Service de Réanimation polyvalente, Hôpital Louis Pasteur, Hôpitaux de Chartres, 28018 Chartres Cedex, France), Jean-Claude Lacherade (Service de Réanimation médicochirurgicale, CH de Poissy/Saint Germain-en-Laye, 10 rue du champ gaillard, 78303 Poissy Cedex, France), Vincent Laudenbach (Service de Pédiatrie, Hôpital Charles Nicolle, 1 rue de Germont, 76031 Rouen, France), Xavier Leverve (LBFA/INSERM 884, Joseph Fourier University, BP53, Grenoble cedex 9, France), Marie-Reine Losser (Hôpital Lariboisière, Pôle Urgence, 2 rue Ambroise Paré, 75010 Paris, France), Alexandre Ouattara (Département d'Anesthésie-réanimation, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié Salpétrière, 47-83 Bd de l'hôpital, 75651 Paris cedex 13, France), Didier Payen de la Garanderie (Hôpital Lariboisière, Pôle Urgence, 2 rue Ambroise Paré, 75010 Paris, France), Gérald Seematter (Service de Médecine Intensive Adulte, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, 46 Rue du Bugnon, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland), Luc Tappy (Institut de Physiologie, Université de Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland), Greet Van den Berghe (Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Catholic University of Leuven, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium), Ilse Vanhorebeek (Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Catholic University of Leuven, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium), Nelly Wion-Barbot (Service d'Endocrinologie Diabétologie, Hôpital A. Michallon, Bd de la Chantourne, 38700 La Tronche, France).

Steering Committee: Marc Leone (Service d'Anesthésie-Réanimation, Hôpital Nord, Chemin des Bourrely, 13915 Marseille, France) (SFAR), Benoît Veber (Service d'Anesthésie-Réanimation, Hôpital Charles Nicolle, 1 rue de Germont, 76031 Rouen, France) (SFAR), Alain Cariou (Service de Réanimation médicale, Hôpital Cochin, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint Jacques, 75679 Paris, France) (SRLF), Didier Barnoud (Service de Réanimation médicale, Hôpital Michallon, Bd de la Chantourne, 38700 La Tronche, France) (SRLF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

PK (Experts Group) is a shareholder of LK2 society, 37554 Saint Avertin, France. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CI initiated the study, proposed to the SFAR and SRLF to support it and organized and supervised the meetings and the experts. All members of the Experts Group were responsible for the analysis of the literature, the elaboration of the recommendations related to their topic and the validation of the whole final recommendations. The Steering Committee was responsible for control of the method and the final elaboration of recommendations. CI and JCP wrote and drafted the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2010_8655_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1:Tables S1, S2 and S3. Table S1. Successive process for developing recommendations; Table S2. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendation; Table S3. Experts recommendations for glucose control in ICU. (DOC 44 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ichai, C., Preiser, JC., for the Société Française d'Anesthésie-Réanimation (SFAR). et al. International recommendations for glucose control in adult non diabetic critically ill patients. Crit Care 14, R166 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9258

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9258