Abstract

Introduction

Statins reduce risk of cardiovascular events and have beneficial pleiotropic effects; both may reduce mortality in critically ill patients. We examined whether statin use was associated with risk of death in general intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

Methods

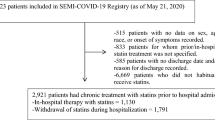

Cohort study of 12,483 critically ill patients > 45 yrs of age with a first-time admission to one of three highly specialized ICUs within the Aarhus University Hospital network, Denmark, between 2001 and 2007. Statin users were identified through population-based prescription databases. We computed cumulative mortality rates 0-30 days and 31-365 days after ICU admission and mortality rate ratios (MRRs), using Cox regression analysis controlling for potential confounding factors (demographics, use of other cardiovascular drugs, comorbidity, markers of social status, diagnosis, and surgery).

Results

1882 (14.3%) ICU patients were current statin users. Statin users had a reduced risk of death within 30 days of ICU admission [users: 22.1% vs. non-users 25.0%; adjusted MRR = 0.76 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.69 to 0.86)]. Statin users also had a reduced risk of death within one year after admission to the ICU [users: 36.4% vs. non-users 39.9%; adjusted MRR = 0.79 (95% CI: 0.73 to 0.86)]. Reduced risk of death associated with current statin use remained robust in various subanalyses and in an analysis using propensity score matching. Former use of statins and current use of non-statin lipid-lowering drugs were not associated with reduced risk of death.

Conclusions

Preadmission statin use was associated with reduced risk of death following intensive care. The associations seen could be a pharmacological effect of statins, but unmeasured differences in characteristics of statin users and non-users cannot be entirely ruled out.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is substantial evidence that statins - widely used lipid-lowering drugs - are effective in reducing major cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with arteriosclerotic disease, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia [1–4]. Experimental studies reported evidence that statins may also have anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic and immuno-modulating effects independent of lowering lipids, also referred to as pleiotropic properties [5, 6]. The pleiotropic properties may differ between individual statins, in particular between lipophilic and hydrophilic statins [7–9].

In line with the experimental findings, observational studies have reported a risk reduction [10–12] and profound improvements in the outcome of critical illnesses such as severe infections among statin users [13–17]. Beneficial effects in terms of reduced morbidity and mortality of statins have also been reported among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure and in patients undergoing cardiac or major non-cardiac surgery [18–21].

Patients in intensive care units (ICUs) have a high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, severe infections and thrombotic complications, and almost all ICU patients suffer from the systemic inflammatory response syndrome [22, 23]. Statins could thus have beneficial effects on mortality following ICU admission. The three existing studies on this issue reported conflicting results and were limited by small and highly selected study populations such as patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome or acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS), and assessed mortality only while in the hospital [24–26]. As intensive care treatment is common, expensive and often ends in death, any beneficial effect of statins in this setting has major clinical and public health implications.

We conducted a large cohort study, based on more than 12,000 ICU patients, to examine the extent to which preadmission statin use overall and by specific agent was associated with risk of death in the year following ICU admission.

Materials and methods

Setting

We conducted this cohort study based on prospectively collected data obtained from medical databases in northern Denmark between 1 January, 2001 and 31 December, 2007. The Danish national health care system provides the entire Danish population with unrestricted access to tax-supported public health services and all critically ill patients receive care in public hospitals [27].

Since 1968 every Danish citizen has received at birth a unique civil registration number from the Danish Civil Registration System. This number permits accurate linkage across all Danish registries [28].

The study population comprised all patients admitted for the first time to an ICU in one of three hospitals within the Aarhus University Hospital network (Aalborg, Aarhus and Skejby Hospitals) [29]. All ICUs are highly specialized multidisciplinary units serving both as primary and referral ICUs. Their patients include those with severe respiratory failure requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and patients undergoing organ transplantation.

Intensive care data

ICU patients were identified using a research database (Aarhus University Intensive Care Cohort (AUICC)). Data on use of mechanical ventilation, use of renal replacement therapy, dates of ICU admission and discharge, and civil registration numbers for all patients treated in the three ICUs are recorded by ICU physicians as part of standard department clinical practice and are routinely entered into the AUICC. We did not include in the cohort patients who were admitted for planned postoperative observation of less than 24 hours and did not include patients younger than 45 years of age, a group that is rarely prescribed statins [30]. The study cohort totaled 12,483 eligible ICU patients with a first ICU admission during the study period.

Preadmission use of statins

We used a prescription database covering the entire region since 1998 to identify statin users. The database contain data, transferred electronically from all pharmacies in the region, on types and dosages of all reimbursed drugs prescribed, customers' civil registration numbers and redemption dates [31]. We defined current statin use as at least one filled prescription for statins within 125 days before ICU admission (for details on Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes see Additional file 1) [31]. The 125-day period allowed us to capture most current statin users, because in Denmark few statin prescriptions are expected to last more than 125 days [17, 30]. Among current statin users, we distinguished 'new' and 'long-term' statin users as those who had filled their first statin prescription within 125 days before ICU admission or earlier than 125 days, respectively [32].

Statin users may have been more frequently hospitalized during the exposure defining period before ICU admission than non-users. As no prescriptions are filled during hospitalizations this may lead to misclassification of statin use [33]. We therefore used the Danish National Registry of Patients (NRP) to identify the number of days that study patients were hospitalized within the 125 days before ICU admission (0 days, 1 to 10 days,11 to 25 days, >25 days).

Other prognostic factors

We identified the main diagnosis for the admission requiring intensive care through the Danish NRP. The NRP covers all hospitalizations in Denmark since 1977 and all out-patient hospital visits since 1995 [34]. We grouped patients into eight disease categories: infectious diseases; endocrinology including diabetes; cardiovascular diseases; respiratory diseases; gastrointestinal and liver diseases; cancer; trauma and poisoning; and others (for details on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, see Additional file 1). We also identified the department that transferred the patient to the ICU (surgical/medical). Using the NRP, we obtained information on surgical procedures in the seven days before ICU admission and classified patients as surgical and medical (no surgery within seven days before ICU admission) [35]. To control for comorbidity, we computed the Charlson comorbidity score based on the entire previous discharge history and defined three comorbidity levels: low (score of 0), medium (1 to 2), and high (≥ 3)) [36]. The index includes 19 major disease categories and has been validated as a predictor of mortality [37, 38]. We also retrieved information on alcoholism-related disorders, and prescriptions for disulfiram (ICD and ATC codes are provided in Additional file 1). For the subcohort of patients admitted between 2001 and 2006 we collected data on hemoglobin, white blood cell (WBC) count, platelets, C-reactive protein (CRP) and bilirubin on ICU admission and on the most recent total cholesterol level recorded within six months of ICU admission from laboratory databases. We retrieved prescription data on current use of angiotensin converting enzymes (ACE) inhibitors, beta blockers, and low-dose aspirin, because these drugs may confound studies on clinical effects of statins [18, 39], and on current use of non-statin lipid-lowering drugs, because these drugs are given on almost the same indications as statins but lack the pleiotropic effects (e.g. niacin, bile acid-binding resin and fibric acid derivatives). As a measure of social status, we obtained data on marital status at the time of ICU admission from the Civil Registration System [28].

Mortality data

We accessed data from the Civil Registration System, which contains complete information for the entire Danish population on migration and changes in vital status, including exact date of death, and is updated on a daily basis [28].

Statistical analysis

Follow up began on the date of first-time ICU admission and continued until death, migration, 365 days after ICU admission or 31 December 2008, whichever came first. We computed Kaplan Meier curves and life table estimates for mortality at 30 days and one year for the following variables: preadmission statin use; primary diagnosis; age group; gender; department (medical/surgical); level of Charlson score; alcoholism-related diseases; surgery within seven days (yes/no); need for mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapy; current use of ACE inhibitors, low-dose aspirin or beta blockers; marital status (married, divorced, widowed, never married, or unknown).

We used Cox proportional hazards regression to compute mortality rate ratios (MRRs) for statin users compared with non-users, controlling for all covariates in Tables 1 and 2, except mechanical ventilation, dialysis, and laboratory data because we considered these potential effects of the intervention [40]. We did separate analyses for subgroups defined according to admitting department, surgery, presence of mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, and for former, new, and long-term statin users. As the pleiotropic effects may vary between types of statins we also did a separate analysis for users of the lipophilic simvastatin, and the hydrophilic atorvastatin and pravastatin and used Wald statistics to compute P values for the difference in MRR between types of statins.

To assess possible unmeasured confounding by indication for statin treatment we restricted the analysis to patients with a previous diagnosis of ischemic or unspecified stroke, atherosclerosis, ischemic heart disease or diabetes mellitus. We also repeated the analysis after excluding patients with cancer and for users of non-statin lipid-lowering agents. Details on ICD codes are provided in Additional file 1.

To further control for confounding we conducted a supplementary analysis using propensity score matching [41, 42]. We generated a multivariable logistic regression model that predicted statin use among ICU patients based on the covariate profile listed in Tables 1 and 2, except laboratory data and mechanical ventilation and dialysis, and computed the propensity score for all ICU patients. We then matched each statin user with one non-user using a greedy matching algorithm. All statin users could be matched to a non-user. Propensity score matching decreased the absolute standardized differences of each covariate to values below 0.1 indicating that an adequate balance was achieved. We then used Cox regression analysis to compute 30-day and one-year MRR in the matched cohort.

The assumptions of proportional hazards in all Cox regression models were assessed graphically and found to be appropriate. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record number 2005-41-4782) and the Aarhus University Hospital Registry Board. Data were obtained from Danish registries, which are generally available to researchers and their use does not require informed consent.

Results

Descriptive data

We identified 12,483 first-time ICU patients older than 45 years. Of these, 1,882 (15.1%) were current statin users on admission (Table 1). Simvastatin was by far the most used statin (1391, 73.9%), followed by atorvastin (240, 12.8%), pravastatin (170, 9.0%) and other statins (81, 4.3%). Statin users were more likely to be male, and have higher levels of comorbidity than other ICU patients. Diabetes and cardiovascular diseases were, as expected, more prevalent among statin users than among non-users, whereas cancer and alcoholism-related diseases were less common. Statin users were more frequently users of ACE inhibitors, beta blockers or low-dose aspirin than non-users (Table 2). At ICU admission, statin users had higher average blood levels of creatinine, similar WBC count and slightly lower levels of CRP than non-users.

A total of 151 (8.0%) statin users and 917 (8.7%) non-users were hospitalized for more than 25 days during the 125 days before ICU admission.

30-day mortality

Throughout the follow-up period, statin users had considerably lower risk of death than statin non-users (Figure 1). The risk of death within 30 days after ICU admission was 22.1% among statin users and 25.0% among non-users, corresponding to a crude MRR of 0.85 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.76 to 0.96; Table 3). After control for potential confounders the 30-day MRR was 0.76 (95% CI = 0.68 to 0.85). For all diagnostic categories, except diabetes and infectious diseases, statin use was associated with a reduced risk of death (Figure 2). The MRRs seemed lower for users of simvastatin (MRR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.65 to 0.84) than for other types of statins (atorvastatin MRR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.72 to 1.25; pravastatin MRR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.71 to 1.30); however, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.42).

Exclusion of patients with cancer from the analysis or restriction to patients with cardiovascular diseases or diabetes left the decreased MRRs for statins virtually unchanged. Of note the risk of death seemed not to be reduced by non-statin lipid-lowering drug use (MRR = 1.29, 95% CI = 0.80 to 2.08) or by former statin use (MRR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.73 to 1.06). For new and long-term statin users the adjusted MRRs were 0.68 (95% CI = 0.51 to 0.90) and 0.81 (95% CI = 0.72 to 0.91), respectively.

Further stratified analyses showed an adjusted 30-day MRR of 0.81 (95% CI = 0.67 to 0.97) among ICU patients who had surgery within seven days of ICU admission, and 0.76 (95% CI = 0.66 to 0.87) among ICU patients who had no surgery within seven days.

The propensity score matched analysis yielded a MRR similar to the estimates from the conventional Cox regression analysis (adjusted MRR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.61 to 0.83).

One-year mortality

The one-year risk of death was 36.4% among statin users compared with 39.9% among non-users; crude MRR was 0.84 (95% CI = 0.76 to 0.93) decreasing to 0.79 (95% CI = 0.73 to 0.87) after controlling for confounding factors. The one-year reduction in risk of death remained robust in all diagnostic categories and seemed most pronounced for simvastatin (simvastatin MRR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.70 to 0.85; atorvastatin MRR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.72 to 1.12; pravastatin MRR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.81 to 1.31); however, the difference between statins did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.35). The reduction in risk of death associated with statin use remained virtually unchanged when analyses were restricted to patients without cancer or to patients with cardiovascular disease or diabetes (Figure 3). MRR among new and long-term statin users were 0.80 (95% CI = 0.65 to 0.98) and 0.81 (95% CI = 0.74 to 0.89), respectively. Former statin use and use of non-statin lipid-lowering drugs was not to be associated with reduced risk of death within one year of ICU admission.

The propensity score matched analysis yielded an adjusted MRR of 0.70 (95% CI = 0.62 to 0.80).

Discussion

In this large cohort study we found that preadmission statin use was associated with considerably reduced risk of death among ICU patients. The reduced risk of death remained robust in various subgroup analyses, including among new and long-term statin users. We found no clear association between former statin use and non-statin lipid-lowering drug use and risk of death, which supports a causal association between statin use and reduced risk of death among ICU patients.

Existing studies

Increasing evidence exists that statins may reduce mortality in patients with severe infections including sepsis [13–17] but limited and conflicting data exist on the association between statin use and in-hospital/30-day mortality among general ICU patients. In a 2006 German cohort study of 120 ICU patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, Schmidt and colleagues reported that statin use was associated with substantially reduced in-hospital mortality (MRR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.29 to 0.99), a result consistent with our findings [25]. Also in line with our findings, a recent US study among 178 patients with ALI/ARDS found reduced ICU and in-hospital mortality among statin users (odds ratio (OR) for ICU mortality 0.82, 95% CI = 0.36 to 1.89; OR for in-hospital mortality 0.62, 95% CI = 0.29 to 1.32); however, the relatively small study population hindered a clear interpretation of the risk estimates [26]. In contrast, a 2006 Spanish observational study of 438 patients mechanically ventilated for more than 96 hours reported higher in-hospital mortality among statin users (61%) than non-users (42%; OR = 2.30, 95% CI = 1.08 to 4.89) [24]. All studies included highly selected subgroups of ICU patients and did not adjust for important covariates such as comorbidity and use of other cardiovascular drugs. To our knowledge, no former data exist on the effect of statins on long-term risk of death among ICU patients.

The biological mechanisms underlying our observations are not yet entirely understood. However, the high prevalence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and/or severe infections among ICU patients may increase the risk of fatal venous and arterial thrombotic events by inducing endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerotic plaque instability [43–45]. There is strong experimental evidence that statins have beneficial effects on platelet function, coagulation, fibrinolysis, and plaque formation, as well as inhibitory effects on endothelial dysfunction [46–50]. Also, statins have immuno-modulating effects that may be beneficial during the initial 'hyper-immune' phase of critical illness [5, 23]. Differences in these pleiotropic properties between lipophilic and hydrophilic statins may explain the possible differences between individual statins suggested by our data, although these differences were not statistically significant [7–9]. One randomized controlled trial including 82 patients with acute bacterial infections confirmed that statins reduce the levels of inflammatory cytokines [51].

Limitations

We conducted this study within a tax-financed national health service system with free access to health care, which largely removed referral bias. We had complete and independently collected data on preadmission statin use and one-year mortality, which limited the risk of information and surveillance bias. The relatively large number of ICU patients enabled robust analysis on several ICU subgroups showing consistent results.

The validity of our findings depends ultimately on accurate registration of statin use and the ability to control for confounding. The completeness and nature of the prescription database used makes the measurement of filled prescriptions for statins highly valid [31]. In Denmark, adherence to statin therapy is high, and any influence of non-compliance should therefore be minor, potentially attenuating our mortality estimates towards unity [52]. As few statin users were hospitalized for more than 25 days during the 125 days before ICU admission, misclassification of statin use because of more frequent previous hospitalizations most likely had little influence on our results [33]. We had access to data on a large number of prospectively collected covariates from databases with high validity for surgical procedures, diagnosis codes, and laboratory data. Still, any lack of specificity in routinely recorded data may have reduced our ability to completely remove confounding and most likely would attenuate our findings towards the null. Severe confounding by socioeconomic differences between statin users and non-users is unlikely given the tax-financed Danish public health care system [53, 54]. This is supported by a recent study that found similar reduced risk of all-cause mortality among statin users and non-users when comparing results from the randomised 4S study with results from an observational study based on prescription data [55].

Statins may exert their potential beneficial effects by improving immune dysfunction caused by critical illness. Surrogate physiological measures of severity of illness and inflammation, e.g. CRP and WBC count, may thus be in the pathway between statin use and mortality and do not fulfil the criteria for being confounding factors [40, 55]. We therefore did not adjust for physiological measures, including laboratory data, in the analysis.

Conclusions

In this large cohort study, preadmission use of statins was associated with reduced risk of death within 30 days and one year in general ICU patients. The associations seen could be a pharmacological effect of statin use; however, it remains to be fully clarified whether differences in characteristics of statin users and non-users may explain at least part of the associations found.

Key messages

-

In experimental studies statins have shown to have anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic and immuno-modulating effects independent of lowering lipids, which may reduce mortality from critical illness.

-

In observational studies statin use has been associated with reduced mortality following major surgery and severe infections.

-

We found that preadmission statin use is associated with reduced short- and long-term mortality following intensive care.

-

The beneficial effects may be most pronounced for users of simvastatin.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

angiotensin converting enzyme

- ALI/ARDS:

-

acute lung injuri/acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- AUICC:

-

Aarhus University Intensive Care Cohort

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ICD:

-

ICD International Classification of Diseases

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- MRR:

-

mortality rate ratio

- NRP:

-

National Register of Patients

- WBC:

-

white blood cell.

References

Ehrenstein MR, Jury EC, Mauri C: Statins for atherosclerosis--as good as it gets? N Engl J Med 2005, 352: 73-75. 10.1056/NEJMe048326

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R: Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005, 366: 1267-1278. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1

Strandberg TE, Pyorala K, Cook TJ, Wilhelmsen L, Faergeman O, Thorgeirsson G, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J: Mortality and incidence of cancer during 10-year follow-up of the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 2004, 364: 771-777. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16936-5

Long-term effectiveness and safety of pravastatin in 9014 patients with coronary heart disease and average cholesterol concentrations: the LIPID trial follow-up Lancet 2002, 359: 1379-1387. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08351-4

Novack V, Terblanche M, Almog Y: Do statins have a role in preventing or treating sepsis. Crit Care 2006, 10: 113. 10.1186/cc3972

Terblanche M, Almog Y, Rosenson RS, Smith TS, Hackam DG: Statins and sepsis: multiple modifications at multiple levels. Lancet Infect Dis 2007, 7: 358-368. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70111-1

Colli S, Eligini S, Lalli M, Camera M, Paoletti R, Tremoli E: Vastatins inhibit tissue factor in cultured human macrophages. A novel mechanism of protection against atherothrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997, 17: 265-272.

Corsini A, Bellosta S, Baetta R, Fumagalli R, Paoletti R, Bernini F: New insights into the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of statins. Pharmacol Ther 1999, 84: 413-428. 10.1016/S0163-7258(99)00045-5

Fehr T, Kahlert C, Fierz W, Joller-Jemelka HI, Riesen WF, Rickli H, Wuthrich RP, Ammann P: Statin-induced immunomodulatory effects on human T cells in vivo. Atherosclerosis 2004, 175: 83-90. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.02.016

Almog Y, Shefer A, Novack V, Maimon N, Barski L, Eizinger M, Friger M, Zeller L, Danon A: Prior statin therapy is associated with a decreased rate of severe sepsis. Circulation 2004, 110: 880-885. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138932.17956.F1

Hackam DG, Mamdani M, Li P, Redelmeier DA: Statins and sepsis in patients with cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort analysis. Lancet 2006, 367: 413-418. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68041-0

Garde EM, Hak E, Souverein PC, Hoes AW, Bosch JM, Leufkens HG: Statin treatment and reduced risk of pneumonia in patients with diabetes. Thorax 2006, 61: 957-961. 10.1136/thx.2006.062885

Almog Y, Novack V, Eisinger M, Porath A, Novack L, Gilutz H: The effect of statin therapy on infection-related mortality in patients with atherosclerotic diseases. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 372-378. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253397.42079.D5

Kruger P, Fitzsimmons K, Cook D, Jones M, Nimmo G: Statin therapy is associated with fewer deaths in patients with bacteraemia. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 75-79. 10.1007/s00134-005-2859-y

Liappis AP, Kan VL, Rochester CG, Simon GL: The effect of statins on mortality in patients with bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 33: 1352-1357. 10.1086/323334

Thomsen RW, Hundborg HH, Johnsen SP, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT, Schonheyder HC, Lervang HH: Statin use and mortality within 180 days after bacteremia: a population-based cohort study. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 1080-1086. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000207345.92928.E4

Thomsen RW, Riis A, Kornum JB, Christensen S, Johnsen SP, Sorensen HT: Preadmission use of statins and outcomes after hospitalization with pneumonia: population-based cohort study of 29,900 patients. Arch Intern Med 2008, 168: 2081-2087. 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2081

Kapoor AS, Kanji H, Buckingham J, Devereaux PJ, McAlister FA: Strength of evidence for perioperative use of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ 2006, 333: 1149. 10.1136/bmj.39006.531146.BE

Lindenauer PK, Pekow P, Wang K, Gutierrez B, Benjamin EM: Lipid-lowering therapy and in-hospital mortality following major noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2004, 291: 2092-2099. 10.1001/jama.291.17.2092

Mancini GB, Etminan M, Zhang B, Levesque LE, FitzGerald JM, Brophy JM: Reduction of morbidity and mortality by statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006, 47: 2554-2560. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.039

Strippoli GF, Navaneethan SD, Johnson DW, Perkovic V, Pellegrini F, Nicolucci A, Craig JC: Effects of statins in patients with chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2008, 336: 645-651. 10.1136/bmj.39472.580984.AE

Attia J, Ray JG, Cook DJ, Douketis J, Ginsberg JS, Geerts WH: Deep vein thrombosis and its prevention in critically ill adults. Arch Intern Med 2001, 161: 1268-1279. 10.1001/archinte.161.10.1268

Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE: The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 2003, 348: 138-150. 10.1056/NEJMra021333

Fernandez R, De PV, Artigas A: Statin therapy prior to ICU admission: protection against infection or a severity marker? Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 160-164. 10.1007/s00134-005-2743-9

Schmidt H, Hennen R, Keller A, Russ M, Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K, Buerke M: Association of statin therapy and increased survival in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 1248-1251. 10.1007/s00134-006-0246-y

Kor DJ, Iscimen R, Yilmaz M, Brown MJ, Brown DR, Gajic O: Statin administration did not influence the progression of lung injury or associated organ failures in a cohort of patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2009, in press.

Health Care:Denmark. Copenhagen, Denmark: Ministry of the Interior and Health; 2003. [http://www.sum.dk/Aktuelt/Publikationer/UK_Healthcare_in_DK.aspx]

Frank L: Epidemiology. When an entire country is a cohort. Science 2000, 287: 2398-2399. 10.1126/science.287.5462.2398

Health Care in Denmark[http://www.rm.dk/Om+regionen/English]

The Danish Medicines Product Statistics[http://www.laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk]

Gaist D, Sorensen HT, Hallas J: The Danish prescription registries. Dan Med Bull 1997, 44: 445-448.

Ray WA: Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol 2003, 158: 915-920. 10.1093/aje/kwg231

Suissa S: Immeasurable time bias in observational studies of drug effects on mortality. Am J Epidemiol 2008, 168: 329-335. 10.1093/aje/kwn135

Andersen TF, Madsen M, Jorgensen J, Mellemkjoer L, Olsen JH: The Danish National Hospital Register. A valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull 1999, 46: 263-268.

Le G Jr, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F: A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 1993, 270: 2957-2963. 10.1001/jama.270.24.2957

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987, 40: 373-383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

de GV, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM: How to measure comorbidity. a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol 2003, 56: 221-229. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00585-1

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992, 45: 613-619. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8

Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Levin R, Avorn J: Selective prescribing led to overestimation of the benefits of lipid-lowering drugs. J Clin Epidemiol 2006, 59: 819-828. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.012

Rothman KJ: Epidemiology, an introduction. 1st edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Sturmer T, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Avorn J, Glynn RJ: Propensity Score Calibration and its Alternatives. Am J Epidemiol 2007, 165: 1122-1123. 10.1093/aje/kwm068

Sturmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S: A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol 2006, 59: 437-447. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.004

Stoll G, Bendszus M: Inflammation and atherosclerosis: novel insights into plaque formation and destabilization. Stroke 2006, 37: 1923-1932. 10.1161/01.STR.0000226901.34927.10

Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Farrington P, Vallance P: Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med 2004, 351: 2611-2618. 10.1056/NEJMoa041747

Smeeth L, Cook C, Thomas S, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Vallance P: Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet 2006, 367: 1075-1079. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2

Dichtl W, Dulak J, Frick M, Alber HF, Schwarzacher SP, Ares MP, Nilsson J, Pachinger O, Weidinger F: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors regulate inflammatory transcription factors in human endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003, 23: 58-63. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000043456.48735.20

Diomede L, Albani D, Sottocorno M, Donati MB, Bianchi M, Fruscella P, Salmona M: In vivo anti-inflammatory effect of statins is mediated by nonsterol mevalonate products. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001, 21: 1327-1332. 10.1161/hq0801.094222

Pruefer D, Makowski J, Schnell M, Buerke U, Dahm M, Oelert H, Sibelius U, Grandel U, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Meyer J, Darius H, Buerke M: Simvastatin inhibits inflammatory properties of Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin. Circulation 2002, 106: 2104-2110. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034048.38910.91

Steiner S, Speidl WS, Pleiner J, Seidinger D, Zorn G, Kaun C, Wojta J, Huber K, Minar E, Wolzt M, Kopp CW: Simvastatin blunts endotoxin-induced tissue factor in vivo. Circulation 2005, 111: 1841-1846. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158665.27783.0C

Doggen CJ, Lemaitre RN, Smith NL, Heckbert SR, Psaty BM: HMG CoA reductase inhibitors and the risk of venous thrombosis among postmenopausal women. J Thromb Haemost 2004, 2: 700-701. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00696.x

Novack V, Eisinger M, Frenkel A, Terblanche M, Adhikari NK, Douvdevani A, Amichay D, Almog Y: The effects of statin therapy on inflammatory cytokines in patients with bacterial infections: a randomized double-blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1255-1260. 10.1007/s00134-009-1429-0

Larsen J, Andersen M, Kragstrup J, Gram LF: High persistence of statin use in a Danish population: compliance study 1993-1998. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2002, 53: 375-378. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01563.x

Thomsen RW, Johnsen SP, Olesen AV, Mortensen JT, Boggild H, Olsen J, Sorensen HT: Socioeconomic gradient in use of statins among Danish patients: population-based cross-sectional study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005, 60: 534-542. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02494.x

Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Eurich DT, Padwal RS, Marrie TJ: Statins and outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with community acquired pneumonia: population based prospective cohort study. BMJ 2006, 333: 999. 10.1136/bmj.38992.565972.7C

Tannen RL, Weiner MG, Xie D: Use of primary care electronic medical record database in drug efficacy research on cardiovascular outcomes: comparison of database and randomised controlled trial findings. BMJ 2009, 338: b81. 10.1136/bmj.b81

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible through financial support from the Danish Medical Research Council (Grant 271-05-0511), and from 'Klinisk Epidemiologisk Forskningsfond', Denmark. The sponsors had no influence on study design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the article and the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SC, RWT, AL, ET and HTS conceived the study idea. SC and HTS designed the study. RJ and KML collected the data. SC, HTS, MBJ and LP analysed the data. All authors interpreted the findings. SC and RWT reviewed the literature. SC wrote the first draft and all authors edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2009_8332_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes. Word document containing ICD and ATC codes for diagnoses and drugs included in the analyses of the current study. (DOC 27 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Christensen, S., Thomsen, R.W., Johansen, M.B. et al. Preadmission statin use and one-year mortality among patients in intensive care - A cohort study. Crit Care 14, R29 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc8902

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc8902