Abstract

Mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) who require intubation or support with inotropes in an intensive care unit setting remains extremely high (up to 50%). Systematic use of objective severity-of-illness criteria, such as the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), British Thoracic Society CURB-65 (an acronym meaning Confusion, Urea, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, age ≥65 years), or criteria developed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society, to aid site-of-care decisions for pneumonia patients is emerging as a step forward in patient management. Experience with the Predisposition, Infection, Response, and Organ dysfunction (PIRO) score, which incorporates key signs and symptoms of sepsis and important CAP risk factors, may represent an improvement in staging severe CAP. In addition, it has been suggested that implementing a simple care bundle in the emergency department will improve management of CAP, using five evidence-based variables, with immediate pulse oxymetry and oxygen assessment as the cornerstone and initial step of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an acute illness with clinical features of lower respiratory tract infection characterized by new radiological shadowing and no other explanation for the illness. CAP is a separate entity from nursing home pneumonia and other health care associated pneumonia. There are many definitions of severe CAP, and the best way to define severity is controversial. Pragmatically, severe CAP can be defined as disease that necessitates admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) [1, 2], which is the definition used in many clinical trials. However, more systematic criteria that permit integration of objective measurement into assessment and avoid variation caused by differing ICU admittance policies across institutions are desirable [3]. Even with the use of such criteria (discussed in greater detail below), the decision to hospitalize or to admit to an ICU relies heavily on physician judgment, particularly the case of illness in younger patients [4].

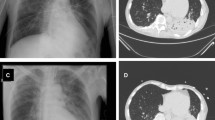

Severe CAP is a progressive disease, and in the event of evolution from a local to a systemic infection the following spectrum of sepsis-related complications may develop (Figure 1): sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Approximately 50% of CAP admissions to Spanish ICUs are associated with septic shock [5]. Progression of severe CAP is associated with hypercoagulation, hypotension, alteration of the microcirculation, and ultimately multiple organ dysfunction. Once multiple organ dysfunction has developed, patient management is independent of the causative pathogen.

Approximately 4 million adults develop CAP annually in the USA [6]. Among hospitalized CAP patients in Europe and the USA, rates of severe CAP range from 6.6% to 16.7% [4, 7–10]. Mortality from severe CAP is high worldwide, with pneumonia/influenza as the eighth leading cause of death in the USA, accounting for 0.3% of deaths in 2004 [6]. Nearly all patients who die as a consequence of severe CAP develop severe sepsis or septic shock. ICU-based studies in the UK and Spain report mortality rates of 20% to 50% in severe CAP patients, depending on admission criteria [11–13].

The high rates of mortality due to severe CAP are also highlighted by the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team prospective study, which compared characteristics of patient groups who did (n = 170) and did not (n = 1,169) require ICU admission [14]. This study showed that CAP was the primary cause of hospital death in both groups (73% in ICU patients versus 74% in non-ICU patients). Mortality was almost four times higher in ICU patients than in non-ICU patients (18% versus 5%; P < 0.0001) [14]. Despite advances in antimicrobial therapy, mortality due to pneumonia has remained more or less constant since penicillin became routinely available [15, 16].

Notably, admissions to the ICU due to severe CAP are rising, which is a multifactorial phenomenon, related not only to the compromised immune systems of aging populations but also to a trend toward recommending that such patients be treated in critical care settings. In a study of 172 ICUs that admit adults across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, there were 301,871 admissions, including 17,869 CAP admissions, in the period from 1996 to 2004 [17]. Total annual admissions increased by 24% during this period, whereas annual admission due to CAP increased by a massive 128%. In addition, a large observational cohort study of elderly Medicare recipients showed that during the year 1997 there were 623,718 hospital admissions for CAP among Medicare recipients aged 65 or over, accounting for an incidence of 18.3 per 1,000 [18]. Of these, 4 per 1,000 required ICU admission. The incidence rose from 8.4 per 1,000 in those aged 65 to 69 years to 48.5 per 1,000 in those aged 90 years or older. Overall hospitalized mortality was 10.6%, doubling from 7.8% in those aged 65 to 69 years to 15.4% in those aged 90 or older. According to US census estimates, the annual number of hospitalized CAP cases is expected to rise to 750,000 and 1 million in the years 2010 and 2020, respectively, because of the disproportionate growth of the elderly population. These figures therefore highlight the growing challenge posed to hospital and ICU staff by severe CAP.

For each patient, the following questions must be asked: what is the diagnosis, should the patient be hospitalized, and should the patient be admitted to the ICU?

Risk factors in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

Early identification of patients at risk for severe CAP can aid patient management. Although age is an important risk factor for development of CAP, co-morbidities also play an important part in determining the risk for pneumonia and disease severity. Physicians should therefore take into account any history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), renal insufficiency/dialysis, chronic heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, chronic neurologic disease, and chronic liver disease/alcohol abuse when they determine patient management. In patients older than 60 years of age, risk is further increased in the presence of asthma, alcoholism, or immunosuppression, and in institutionalized patients [19].

Other factors that have been implicated in increasing mortality in severe CAP patients include male sex, and the development of acute respiratory failure, severe sepsis/septic shock, and bacteremia [20]. Some specific pathogens also carry an increased risk for severe CAP. The most common organisms observed in patients admitted to the ICU are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Haemophilus influenzae. The most common lethal pathogens are S. pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and L. pneumophila, and the latter two pathogens are frequently associated with a need for mechanical ventilation [21]. The most prevalent pathogen associated with severe CAP, namely S. pneumoniae, is responsible for two-thirds of CAP-related deaths. Although the worst outcome is associated with infection with Gram-negative organisms, such infections are relatively infrequent.

Signs of disease progression during the first 72 hours after hospital admission are also associated with increased risk for death. For patients without co-morbidities, presence of multilobar consolidation and need for mechanical ventilation or inotropic support are associated with greater disease severity and higher mortality rates [22].

Emerging evidence suggests that critically ill patients with severe CAP and COPD are more likely to need mechanical ventilation and carry increased risk for mortality [23, 24]. In a secondary analysis of a prospective study in which 428 immunocompetent patients admitted to the ICU for severe CAP were evaluated, all patients were stratified according to the presence or absence of COPD [24]. In total, 176 COPD patients were compared with 252 non-COPD patients, and COPD proved to be an important risk factor for mortality. In COPD patients, both mechanical ventilation (odds ratio = 2.78, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.63 to 4.74) and ICU mortality (odds ratio = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.43) rates were higher than in non-COPD patients. The ICU mortality rate was 39% in COPD patients initially intubated and 50% in those who did not respond to noninvasive ventilation. Patients with a history of COPD are likely to have more severe signs at presentation: septic shock; tachypnea; lower pH, partial oxygen tension, and oxygen saturation; and greater partial carbon dioxide tension. COPD is more common with increasing age, in male patients, and in patients with diabetes or chronic heart failure [23].

Recent reanalysis of the Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intensive Care Unit (CAPUCI) study, in which patients with severe CAP requiring ICU admission were assessed, has suggested that radiologic progression of pulmonary infiltrates is a significant adverse prognostic feature [25]. In contrast, bacteremia levels appeared not to affect patient outcomes [25].

Who should be considered for hospital admission?

Site-of-care assessment based on severity of illness is a vital component of patient management, affecting diagnostic work up and empirical treatment with antibiotics. It is essential to identify patients with severe CAP as early as possible because of its implications for management and mortality.

There are various severity assessment tools, including the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) [26] and the British Thoracic Society CURB-65 (Confusion, Urea, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, age ≥65 years) score [27]. The PSI has been developed primarily to identify those patients who can safely be treated as outpatients (Figure 2). According to this score, the main determinants of pneumonia severity are increasing age, co-morbidity, and vital sign abnormalities. The calculation of the PSI score also requires laboratory, blood gas, and chest radiography data, making this a more problematic set of tests to perform in the emergency room setting.

The PSI has convincingly been validated in several studies, and it allows the confident separation of patients with a mortality risk of up to 3% (PSI classes I to III) from those with risks of 8% (PSI class IV) and 35% (PSI class V). However, it should be noted that although the PSI takes into account renal, heart, cardiovascular or liver disease, and malignancy, it does not include as risk factors COPD or diabetes. The PSI is therefore a useful tool for identifying patients who can be discharged safely, and receive home treatment with antibiotics. The PSI has also been useful in demonstrating equivalence of empirical antibiotics, and showing that delaying appropriate antibiotics worsens survival in classes IV to V pneumococcal bacteremic pneumonia [28].

In contrast to the complexity of the PSI, the British Thoracic Society CURB-65 system uses simple clinical measures and a single laboratory investigation (blood urea), which is readily available in most hospitals (Figure 3) [27]. A simplified version omitting the blood urea nitrogen testing has also been proposed (CRB-65) [29]. As with the PSI, CURB-65/CRB-65 scores are useful in determining which patients may safely be treated at home, and can flag certain hospitalized patients for careful scrutiny and for admission to the ICU if their condition deteriorates. However, these tools have limitations in identifying all patients with severe pneumonia who require ICU admission.

Who should be considered for admission to the intensive care unit?

The decision to admit a patient to the ICU remains one of the most important steps in the management of CAP. One of the limitations of the PSI is that it occasionally underestimates severity, particularly in young patients without co-morbidities who develop severe respiratory failure [4], because hypoxia alone does not score highly enough to categorize such patients as being at high risk. Similarly, CURB-65 may underestimate risk in elderly patients with co-morbidities.

To address these issues, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) recently reviewed risk factors and developed objective major and minor criteria to identify patients who require direct admission to an ICU [1]. The most up-to-date definitions use need for invasive mechanical ventilation or septic shock, requiring vasopressors, as absolute indicators for direct admission to an ICU (Table 1). For patients who do not meet either of these two major criteria, minor criteria have been proposed that are based on CURB-65 and ATS criteria with new additions. For admission to an ICU or high level unit, patients must fulfill at least three of these minor criteria (Table 1). Validation of the use of these objective criteria in a large population of patients (n = 696), of whom 116 were admitted to an ICU, indicated that CURB-65 criteria can be used as an alternative to PSI to identify low-risk patients, and confirmed the ability of the IDSA/ATS guidlines to predict disease severity [9]. In Europe CURB-65, or a variant of this system, remains popular.

Overall, the use of established guidelines to assess whether a patient should be admitted to the ICU can yield different answers, depending on which guideline is used. Clinical experience and judgment should not be underestimated in this setting. There is still room for improvement in incorporating the signs and symptoms of systemic involvement, such as sepsis, into the management of patients with severe CAP.

Although factors reflecting acute respiratory failure and severe sepsis or septic shock are independent predictors of severity in CAP [20], and sepsis severity at admission significantly affects outcome [29], such factors have not yet been systematically implemented into risk classification for CAP patients. A possible advance in this area could be the development, validation, and incorporation into management tools of emerging biomarkers for diseases [30, 31]. Biomarkers identified as markers of sepsis may complement traditional scoring factors in predicting outcomes, but this approach has yet to be validated.

The problem has been that, although a systemic inflammatory response underlies the acute respiratory failure observed in severe CAP, and increases the risk for sepsis, attempts to incorporate the signs of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome into patient management have proved disappointing, because these criteria do not consistently identify severely ill patients [32].

To try to address the need to identify ICU CAP patients at high risk, using readily available clinical data, a new form of classification has been proposed that is analogous to the tumor staging systems used to define aggressive and nonaggressive cancers. Known as the PIRO system, sepsis patients are classified across four domains [33, 34]: Predisposition, Infection, Response, and Organ dysfunction. The rationale underpinning this approach lies in the complex nature of sepsis and overlap with pneumonia. Current opinion holds that the genetic makeup of an individual is likely to be a major determinant of the lifetime predisposition to sepsis, and progress continues to be made in identifying relevant candidate genes [20, 35]. The site of infection, and the nature and spread of the pathogen within the body are also important features. Although some elements of the variables that affect the host response to infection are easy to identify (age, nutritional status, sex, co-morbid conditions, and so on), others are more complex and arise from interactions between inflammation, coagulation, and sepsis.

We have developed an adaptation of the PIRO score that is applicable in the setting of severe CAP, arbitrarily determining a score for the features of severe CAP (Figure 4) [36]. The PIRO system takes into account risk factors, most notably the presence of COPD, in accordance with results showing that CAP patients admitted to ICUs with COPD have a worse prognosis and a worse 28-day survival compared with non-COPD patients [24]. Validation of the PIRO score revealed an excellent correlation between increasing PIRO score and mortality rate (P < 0.001), and between increasing PIRO score and health care resource utilization in terms of the need for mechanical ventilation and length of stay in the ICU (P < 0.001).

PIRO as a mortality risk assessment tool. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; PIRO, Predisposition, Infection, Response, and Organ dysfunction. Reproduced with permission from Rello and coworkers [36].

Although the elements of PIRO should be readily testable in clinical and basic research in sepsis, this approach has yet to be fully evaluated as a novel clinical tool for patient evaluation.

Charles and colleagues [37] recently developed a tool for the prediction of which CAP patients will require intensive respiratory or vasopressors support. The SMART-COP score was developed by studying 882 CAP patients in the Australian CAP Study. The tool was then validated in five external databases. SMART-COP utilizes the measurement of the following (which are also the origin of the acronym SMART-COP): systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography, low albumin levels, respiratory rate (age adjusted), tachycardia, confusion, low oxygen (age-adjusted), and arterial pH (<7.35).

Nonantimicrobial medical management of severe community-acquired pneumonia

When a patient is admitted to the ward or ICU, other important decisions include issues of fluid resucitation; for instance, how much fluid should the patient receive, and which fluid is best? High volume options include the crystalloids (saline and Ringer's solution), whereas lower volume options include hydroxyethyl starch solutions, gelatin, and albumin. The choice of fluid is less important than the timely initiation of fluid resuscitation.

Our clinical experience also indicates that oxygen assessment and antibiotic administration should be done promptly, because postponing oxygenation assessment is associated with a significant delay in initiating antibiotics [38]. This is supported by secondary analysis from a prospective, observational, multicenter study that included 529 patients with severe CAP admitted to the ICUs of 33 hospitals (the CAPUCI study) [38]. Unadjusted linear regression analysis confirmed that a delay in oxygenation assessment of more than 1 hour was associated with an increase in time to first antibiotic dose of 6.13 hours (95% CI = 3.42 to 8.83 hours; P < 0.001). In addition, a delay in oxygenation assessment of more than 3 hours was associated with an increased risk for death (relative risk = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.17 to 4.30). Multivariable analysis, adjusting for potential confounders, revealed that delayed oxygenation assessment (>3 hours) was an independent risk factor of death (hazard ratio = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.22 to 3.50) [38].

Efficacy in ICU admission is an important feature of management. Patients who are admitted to the ICU after being on a medical ward for 1 or 2 days typically have worse outcomes than those who are admitted directly from the emergency department. The need for early ICU admission and prompt intervention for high risk patients has been confirmed by recent data [17, 39]. In a large-scale retrospective analysis, conducted at 172 adult ICUs across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 17,869 cases of CAP were identified [17]. Fifty-nine per cent of cases were admitted to the ICU within 2 days of hospital admission, 21.5% between 2 and 7 days, and 19.5% later than 7 days after hospital admission. Mortality was related to the time between hospital and ICU admissions, with a 46.3% mortality rate seen in those admitted to the ICU within 2 days of hospital admission, rising to 50.4% in those admitted between 2 and 7 days and 57.6% in those admitted later than 7 days after hospital admission. Despite the lower mortality associated with early ICU admission, overall mortality remains high in these patients [17].

Antibiotic treatment

Prompt initiation of antibiotic therapy is also key to good outcome, although this is not always achieved. Common reasons for delaying antibiotic therapy are organizational issues, incorrect diagnosis, and lack or knowledge, experience, or confidence on the part of the physician [40], which can in turn delay obtaining results of microbial cultures.

Effective combination therapy, able to cover the likely microbial pathogens, should be initiated promptly in patients with severe CAP. Combination therapy appears crucial when treating patients with shock, as was shown in a secondary analysis of the CAPUCI study [5]. The results showed that combination antibiotic therapy and monotherapy were equally effective in the absence of shock (n = 259), but combination antibiotic therapy improved outcome in patients with shock (n = 270) [5]. However, the CAPUCI study also showed that mortality in severe CAP patients receiving adequate antibiotics remains high, at 24.2% [41]. This secondary analysis of the CAPUCI database confirmed that shock, acute renal failure, and an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score of above 24 were independently associated with mortality in immunocompetent patients with bacterial CAP who received adequate initial antibiotics and co-morbidity management.

Lujan and colleagues [42] evaluated the effect of discordant empiric therapy on outcomes in bacteremic pneumococcal CAP (n = 100). In this study, 'discordant therapy' was defined as an empiric antimicrobial given for the first 2 days after pneumonia onset that was inactive against S. pneumoniae.

Mortality in patients receiving concordant therapy was 14%; the excess mortality for discordant therapy was 36%. Discordant therapy, multilobar involvement, underlying COPD, and hospitalization during the previous 12 weeks were independently associated with death. This study indicated that, in patients with high severity of disease, persistance of high bacterial burden may be associated with septic shock and death in pneumococcal bacteremic pneumonia [42].

In patients with septic shock, time to starting antibiotics is very important, as indicated by a study of 14 ICUs in Canada and the USA [43]. Assessment of the medical records of 2,731 adult patients with septic shock revealed a strong relationship between any delay in effective antimicrobial initiation and in-hospital mortality. Administration of an antimicrobial effective for isolated or suspected pathogens within the first hour of documented hypotension was associated with a survival rate of 79.9%, whereas each hour of delay over the next 6 hours was associated with an average decrease in survival of 7.6%.

In a further retrospective study conducted in the USA, investigators assessed a random sample of 18,209 Medicare patients who were older than 65 years and who were hospitalized with CAP from July 1998 through March 1999 [39]. The results showed that, for patients not using outpatient antibiotics, initiation of antibiotic treatment within 4 hours of admission significantly improved in-hospital mortality from 7.4% to 6.8% (P = 0.05), and improved 30-day mortality rates from 12.7% to 11.6% (P < 0.01).

The introduction of IDSA/ATS guidelines for antibiotic administration also represents a step forward in patient management. Adherence to these guidelines significantly improved mortality from 33% to 24% (P = 0.05) in a cohort of 529 severe CAP patients treated at 33 Spanish hospitals [41]. In a further study of 99 US patients, adherence to IDSA guidelines significantly improved length of stay from 6.8 to 4.5 days (P < 0.01) and resulted in lower hospital costs (P < 0.05) [44]. Additionally, in another Spanish study of CAP patients receiving ventilatory support (n = 199), patients who were not prescribed an IDSA-compliant antibiotic regimen remained on mechanical ventilation for an average of 3 days longer than patients who received an IDSA-compliant regimen [45]. In a multivariate hazard model, two variables were independently associated with greater durations of mechanical ventilation: development of acute renal failure (hazard ratio = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.02 to 2.12) and prescription of an IDSA-noncompliant regimen (hazard ratio = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.93).

Post-discharge mortality

Whereas regulatory agencies suggest that 28 days is a key time point for patient follow up, mortality associated with CAP continues to occur even after hospital discharge, and at 90 and 180 days patients who were discharged home in a good condition may present with additional symptoms and associated mortality. This issue should be studied in detail to inform future therapeutic guidelines. The link between inflammation, modulation of inflammation in different conditions, and hypercoagulation is a potential explanation for this unexplained excess mortality, and some patients may benefit from adjuvant therapy while they are hospitalized.

A care bundle for severe community-acquired pneumonia

The data presented here, based in part on our own research experience, suggest that a care bundle for severe CAP patients – incorporating the key elements shown in Figure 5 – would be a valuable tool. Risk assessment should include pulse oxymetry and point-of-care lactate for early identification of hypoxemia or hypoperfusion. This should be followed by a combination of measures aimed at reducing bacterial load (antibiotics) and improving oxygenation and microcirculation. Identification of patients who are at risk for invasive respiratory and vasopressor support is crucial because delayed ICU admission is associated with reduced survival. Newer tools for risk stratification, such as the PIRO score, would enhance recognition of patients who require adjunctive therapy. Incorporating microbiologic information, with early detection of bacteremia using polymerase chain reaction and DNAemia, will be the next steps in enhancing management of severe CAP.

Conclusion

Although there is now considerable evidence that it is extremely important to ensure that all patients with severe CAP receive timely and appropriate antimicrobial therapy, it is clear that – even with appropriate therapy – severe CAP continues to be associated with an unacceptably high mortality rate worldwide.

Systematic use of objective criteria to aid site-of-care decision making in pneumonia patients is emerging as a step forward in patient management. The PSI can identify those patients who can be discharged and treated at home safely, but occasionally it underestimates severity, particularly in young patients without co-morbidities who have severe respiratory failure. In addition, CURB-65 provides a simple tool that can identify patients who are at high risk for mortality and who might benefit from early ICU admission. Early admission to the ICU may be an important way to improve survival, and the decision to admit a patient to the ICU remains among the most important steps in the management of CAP. More studies of early intervention and prompt ICU admission are needed to address this issue. Adherence to IDSA/ATS guidelines (objective major and minor criteria for direct admission to an ICU) also provides a way to improve patient outcome. It should be noted, however, that physician experience will continue to play a vital role in achieving early ICU admission and prompt intervention in high-risk patients. The PIRO score, which incorporates key signs and symptoms of sepsis and risk factors for severe CAP into the CURB-65 score, highlights the limitations of CURB-65 as a track and trigger tool.

Because postponing oxygenation assessment adversely affects outcome, we suggest that implementing a care bundle to improve management of CAP in the emergency department – using simple evidence-based variables, including immediate pulse oxymetry and oxygenation assessment as the cornerstone and initial step in treatment – may be a means to optimize outcomes in severe CAP.

Abbreviations

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- CAP:

-

community-acquired pneumonia

- CAPUCI:

-

Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intensive Care Unit

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CURB-65:

-

Confusion, Urea, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, age ≥65 years

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IDSA:

-

Infectious Diseases Society of America

- PIRO:

-

Predisposition, Infection, Response, and Organ dysfunction

- PSI:

-

Pneumonia Severity Index

- SMART-COP:

-

systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography, low albumin levels, respiratory rate, tachycardia, confusion, low oxygen, and arterial pH.

References

Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG, Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society: Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007, 44(suppl 2):S27-S72. 10.1086/511159

Kamath AV, Myint PK: Recognising and managing severe community acquired pneumonia. Br J Hosp Med 2006, 26: 76-78.

Oosterheert JJ, Bonten MJ, Hak E, Schneider MM, Hoepelman AI: Severe community-acquired pneumonia: what's in a name? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2003, 16: 153-159.

Marrie TJ, Shariatzadeh MR: Community-acquired pneumonia requiring admission to an intensive care unit: a descriptive study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007, 86: 103-111. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3180421c16

Rodríguez A, Mendia A, Sirvent JM, Barcenilla F, de la Torre-Prados MV, Solé-Violán J, Rello J, CAPUCI Study Group: Combination antibiotic therapy improves survival in patients with community-acquired pneumonia and shock. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 1493-1498. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266755.75844.05

National Center for Health Statistics: Health Statistics, 2006.[http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats]

Bauer TT, Welte T, Ernen C, Schlosser BM, Thate-Waschke I, de Zeeuw J, Schultze-Werninghaus G: Cost analyses of community-acquired pneumonia from the hospital perspective. Chest 2005, 128: 2238-2246. 10.1378/chest.128.4.2238

España PP, Capelastegui A, Gorordo I, Esteban C, Oribe M, Ortega M, Bilbao A, Quintana JM: Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 174: 1249-1256. 10.1164/rccm.200602-177OC

Ewig S, de Roux A, Bauer T, García E, Mensa J, Niederman M, Torres A: Validation of predictive rules and indices of severity for community acquired pneumonia. Thorax 2004, 59: 421-427. 10.1136/thx.2003.008110

Riley PD, Aronsky D, Dean NC: Validation of the 2001 American Thoracic Society criteria for severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 2398-2402. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000147443.38234.D2

Woodhead MA, Macfarlane JT, Rodgers FG, Laverick A, Pilkington R, Macrae AD: Aetiology and outcome of severe community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect 1985, 10: 204-210. 10.1016/S0163-4453(85)92463-6

Moine P, Vercken JB, Chevret S, Chastang C, Gajdos P: Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Etiology, epidemiology, and prognosis factors. French Study Group for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in the Intensive Care Unit. Chest 1994, 105: 1487-1495. 10.1378/chest.105.5.1487

Leroy O, Saux P, Bedos JP, Caulin E: Comparison of lev-ofloxacin and cefotaxime combined with ofloxacin for ICU patients with community-acquired pneumonia who do not require vasopressors. Chest 2005, 128: 172-183. 10.1378/chest.128.1.172

Angus DC, Marrie TJ, Obrosky DS, Clermont G, Dremsizov TT, Coley C, Fine MJ, Singer DE, Kapoor WN: Severe community-acquired pneumonia: use of intensive care services and evaluation of American and British Thoracic Society Diagnostic criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166: 717-723. 10.1164/rccm.2102084

Feikin DR, Schuchat A, Kolczak M, Barrett NL, Harrison LH, Lefkowitz L, McGeer A, Farley MM, Vugia DJ, Lexau C, Stefonek KR, Patterson JE, Jorgensen JH: Mortality from invasive pneumococcal pneumonia in the era of antibiotic resistance, 1995–1997. Am J Public Health 2000, 90: 223-229. 10.2105/AJPH.90.2.223

National Center for Health Statistics: Leading causes of death, 1900–1998.[http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lcod.htm]

Woodhead M, Welch CA, Harrison DA, Bellingan G, Ayres JG: Community-acquired pneumonia on the intensive care unit: secondary analysis of 17,869 cases in the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care 2006, 10(suppl 2):S1. 10.1186/cc4927

Kaplan V, Angus DC, Griffin MF, Clermont G, Scott Watson R, Linde-Zwirble WT: Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: age- and sex-related patterns of care and outcome in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165: 766-772.

Mandell LA: Epidemiology and etiology of community-acquired pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2004, 18: 761-776. vii. 10.1016/j.idc.2004.08.003

Neuhaus T, Ewig S: Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia. Med Clin North Am 2001, 85: 1413-1425. 10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70388-6

Rello J, Bodi M, Mariscal D, Navarro M, Diaz E, Gallego M, Valles J: Microbiological testing and outcome of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2003, 123: 174-180. 10.1378/chest.123.1.174

Feldman C, Viljoen E, Morar R, Richards G, Sawyer L, Goolam Mahomed A: Prognostic factors in severe community-acquired pneumonia in patients without co-morbid illness. Respirology 2001, 6: 323-330. 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00352.x

Pifarre R, Falguera M, Vicente-de-Vera C, Nogues A: Characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2007, 101: 2139-2144. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.05.011

Rello J, Rodriguez A, Torres A, Roig J, Sole-Violan J, Garnacho-Montero J, de la Torre MV, Sirvent JM, Bodi M: Implications of COPD in patients admitted to the intensive care unit by community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006, 27: 1210-1216. 10.1183/09031936.06.00139305

Lisboa T, Blot S, Waterer GW, Canalis E, de Mendoza D, Rodriguez A, Rello J, Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intensive Care Units (CAPUCI) Study Investigators: Radiological progression of pulmonary infiltrates predicts a worse prognosis in severe community-acquired pneumonia than bacteremia. Chest 2008, in press.

Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Hanusa BH, Weissfeld LA, Singer DE, Coley CM, Marrie TJ, Kapoor WN: A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997, 336: 243-250. 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402

Lim WS, Eerden MM, Laing R, Boersma WG, Karalus N, Town GI, Lewis SA, Macfarlane JT: Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003, 58: 377-382. 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377

Spindler C, Ortqvist A: Prognostic score systems and community-acquired bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006, 28: 816-823. 10.1183/09031936.06.00144605

Schaaf B, Kruse J, Rupp J, Reinert RR, Droemann D, Zabel P, Ewig S, Dalhoff K: Sepsis severity predicts outcome in community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2007, 30: 517-524. 10.1183/09031936.00021007

Christ-Crain M, Morgenthaler NG, Stolz D, Müller C, Bingisser R, Harbarth S, Tamm M, Struck J, Bergmann A, Müller B: Pro-adrenomedullin to predict severity and outcome in community-acquired pneumonia [ISRCTN04176397]. Crit Care 2006, 10: R96. 10.1186/cc4443

Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, Müller C, Miedinger D, Huber PR, Zimmerli W, Harbarth S, Tamm M, Müller B: Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 174: 84-93. 10.1164/rccm.200512-1922OC

Dremsizov T, Clermont G, Kellum JA, Kalassian KG, Fine MJ, Angus DC: Severe sepsis in community-acquired pneumonia: when does it happen, and do systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria help predict course? Chest 2006, 129: 968-978. 10.1378/chest.129.4.968

Marshall JC: Biomarkers of sepsis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2006, 8: 351-357. 10.1007/s11908-006-0045-1

Opal SM: Concept of PIRO as a new conceptual framework to understand sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005, 6(suppl):S55-S60. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161580.79526.4C

Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP, Weissfeld LA, Yealy DM, Pinsky MR, Fine J, Krichevsky A, Delude RL, Angus DC, GenIMS Investigators: Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis: results of the Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) Study. Arch Intern Med 2007, 167: 1655-1663. 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655

Rello J, Rodriguez A, Lisboa T, Gallego M, Lujan M, Wunderink R: Assessment of severity in ICU patients with community-acquired pneumonia using PIRO score. Crit Care Med 2008.

Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, Fine MJ, Fuller AJ, Stirling R, Wright AA, Ramirez JA, Christiansen KJ, Waterer GW, Pierce RJ, Armstrong JG, Korman TM, Holmes P, Obrosky DS, Peyrani P, Johnson B, Hooy M, Australian Community-Acquired Pneumonia Study Collaboration, Grayson ML: SMART-COP: a tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2008, 47: 375-384. 10.1086/589754

Blot SI, Rodriguez A, Solé-Violán J, Blanquer J, Almirall J, Rello J, Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intensive Care Units (CAPUCI) Study Investigators: Effects of delayed oxygenation assessment on time to antibiotic delivery and mortality in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 2509-2514. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266825.19629.BA

Houck PM, Bratzler DW, Nsa W, Ma A, Bartlett JG: Timing of antibiotic administration and outcomes for Medicare patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2004, 164: 637-644. 10.1001/archinte.164.6.637

Barlow G, Nathwani D, Myers E, Sullivan F, Stevens N, Duffy R, Davey P: Identifying barriers to the rapid administration of appropriate antibiotics in community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008, 61: 442-451. 10.1093/jac/dkm462

Bodí M, Rodríguez A, Solé-Violán J, Gilavert MC, Garnacho J, Blanquer J, Jimenez J, de la Torre MV, Sirvent JM, Almirall J, Doblas A, Badía JR, García F, Mendia A, Jordá R, Bobillo F, Vallés J, Broch MJ, Carrasco N, Herranz MA, Rello J, Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intensive Care Units (CAPUCI) Study Investigators: Antibiotic prescription for community-acquired pneumonia in the intensive care unit: impact of adherence to Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on survival. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41: 1709-1716. 10.1086/498119

Lujan M, Gallego M, Fontanals D, Mariscal D, Rello J: Prospective observational study of bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia: effect of discordant therapy on mortality. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 625-631. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000114817.58194.BF

Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, Light B, Parrillo JE, Sharma S, Suppes R, Feinstein D, Zanotti S, Taiberg L, Gurka D, Kumar A, Cheang M: Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 1589-1596. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9

Orrick JJ, Segal R, Johns TE, Russell W, Wang F, Yin DD: Resource use and cost of care for patients hospitalised with community acquired pneumonia: impact of adherence to Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines. Pharmacoeconomics 2004, 22: 751-757. 10.2165/00019053-200422110-00005

Shorr AF, Bodi M, Rodriguez A, Sole-Violan J, Garnacho-Montero J, Rello J, CAPUCI Study Investigators: Impact of antibiotic guideline compliance on duration of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2006, 130: 93-100. 10.1378/chest.130.1.93

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a presentation made at a satellite symposium, 'Severe community-acquired pneumonia update: mortality, mechanisms and medical intervention', held on 21 April 2008 in Barcelona, Spain as part of the 18th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID). It is published as part of Critical Care Volume 12 Supplement 6, 2008. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://ccforum.com/supplements/12/S6

Publication of the supplement has been sponsored by Novartis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he is serving in the Speakers Bureau and Advisory Board for Novartis, Wyeth, and Pfizer.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rello, J. Demographics, guidelines, and clinical experience in severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care 12 (Suppl 6), S2 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc7025

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc7025