Abstract

Introduction

Prediction of death and prolonged mechanical ventilation is important in terms of projecting resource utilization and in establishing protocols for clinical studies of acute lung injury (ALI). We aimed to identify risk factors for a combined end-point of death and/or prolonged ventilator dependence and developed an ALI-specific prediction model.

Methods

In this retrospective analysis of three multicenter clinical studies, we identified predictors of death or ventilator dependence from variables prospectively recorded during the first three days of mechanical ventilation. After the prediction model was derived in an international cohort of patients with ALI, it was validated in two independent samples of patients enrolled in a clinical trial involving 17 academic centers and a North American population-based cohort.

Results

A combined end-point of death and/or ventilator dependence at 14 days or later occurred in 68% of patients in the international cohort, 60% of patients in the clinical trial, and 59% of patients in the population-based cohort. In the derivation cohort, a model based on age, oxygenation index on day 3, and cardiovascular failure on day 3 predicted death and/or ventilator dependence. The prediction model performed better in the clinical trial validation cohort (area under the receiver operating curve 0.81, 95% confidence interval 0.77 to 0.84) than in the population-based validation cohort (0.71, 95% confidence interval 0.65 to 0.76).

Conclusion

A model based on age and cardiopulmonary function three days after the intubation is able to predict, moderately well, a combined end-point of death and/or prolonged mechanical ventilation in patients with ALI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although a significant number of patients with acute lung injury (ALI) die or require prolonged mechanical ventilation, the tools for predicting mortality and morbidity in this group of patients are limited [1, 2]. Parameters related to the degree of impairment in pulmonary function and nonpulmonary organ failures have been associated with increased mortality and prolonged mechanical ventilation in patients with ALI, and in mechanically ventilated patients in general [1–11]. Compared with values collected on day 1, evolution of the disease and response to treatment during the first three days of mechanical ventilation provide valuable prognostic information [1, 2, 12].

The present study analyzed potential predictors of outcome from mechanical ventilation in patients with ALI in three recent prospective cohorts with the following specific aims: to identify risk factors for death and/or ventilator dependence; to develop an ALI-specific prediction model; and to validate the prediction model in independent samples from both population-based and clinical trial databases, in order to determine the potential value of the model for clinical decision making and clinical trial design in patients who are likely to die or require prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Materials and methods

In this retrospective study, we used data from patients with ALI enrolled in three recent prospective cohorts. The detailed protocols of these three studies, namely the Second International Study of Mechanical Ventilation (VENTILA) [13], the ARDS-net clinical trial (low tidal volume [14] and lisophylline [15]), and the King County Lung Injury Project (KCLIP) [16], have previously been reported. The studies were approved by local ethics committees in each participating institution. ALI and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were defined according to the American-European Consensus conference [17] in all three cohorts.

Outcome measures

The main outcome of interest was the composite outcome of death in hospital and/or ventilator dependence for more than two weeks after intubation (less than 14 ventilator-free days). There are a number of reasons why we selected the combined end-point of death and/or ventilator dependence. First, specific intensive care unit interventions that may be applied at the bedside or tested in a clinical trial may affect both survival and the duration of mechanical ventilation. Second, during the first few days of mechanical ventilation it may be difficult to discriminate between patients who will die in the hospital and those who require prolonged mechanical ventilation but ultimately will survive hospitalization. Third, the fact that a significant proportion of survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation experience a long-term decrease in quality of life may be particularly important in the informed consent process and end-of life discussions in patients with respiratory failure who are at high risk for death or prolonged mechanical ventilation. Finally, analogous to the concept of ventilator-free days, the combined end-point may be a more sensitive outcome for the design of clinical trials testing specific therapeutic interventions.

Patient groups

Derivation cohort

From the VENTILA study database, we identified patients with ALI who were alive and mechanically ventilated through an endotracheal tube for at least three days. Patients who died, who underwent earlier tracheostomy, or who were noninvasively ventilated on or before day 3 after initial intubation were excluded.

Validation cohorts

Patients with ALI enrolled into the two ARDS-net studies (clinical trial sample) and KCLIP study (population-based sample), who were alive and mechanically ventilated through an endotracheal tube on day 3 after intubation, were identified. Those who died or were ventilated noninvasively during the first three days after initial intubation were excluded. Tracheostomy data were not available in the validation cohorts.

Measures and parameters recorded

A number of variables, prospectively collected during the first three days of mechanical ventilation, were abstracted from the databases. Baseline characteristics abstracted included age, sex, body mass index, severity of illness (Simplified Acute Physiology Score [SAPS] II [18] and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [19]), and underlying ALI risk factors (pulmonary and extrapulmonary). Respiratory variables included peak and plateau airway pressures, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), arterial oxygen tension (PaO2)/fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio, arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2), oxygenation index [8], and minute volume needed to bring PaCO2 to 40 mmHg (VE40) [6]. The following measures of nonpulmonary organ failures were also abstracted: serum creatinine (kidney), serum bilirubin (liver), platelet count (hematologic variable), Glasgow Coma Scale score (neurologic variable), and (arterial hypotension or the use of vasopressors (cardiovascular variable).

Oxygenation index was calculated using the following formula: mean airway pressure × FiO2/PaO2. Mean airway pressure was calculated as (peak airway pressure + PEEP)/2. VE40 was calculated as (minute volume × PaCO2)/40. Cardiovascular failure was defined as systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg or the use of vasopressors, defined as follows: > 5 μg/kg per min dopamine or any dose of norepinephrine (noradrenaline), epinephrine (adrenalilne), vasopressin, or phenylephrine.

Statistical analysis

Data are summarized as median (interquartile range) or as proportions. Univariate logistic regression analysis and recursive partitioning were used to identify variables associated with increased risk for death or ventilator dependence in the derivation cohort. Stepwise multiple logistic regression identified combination of variables with the best predictive ability. Variables were included in the model if they were biologically plausible and associated with the outcome of interest in univariate analysis (P < 0.1 or odds ratio ≥ 2.0 for nominal variables, or a median split of continuous variables). The final model was selected by backward elimination of nonsignificant variables. Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics [20] were used to determine the calibration of the model in each sample. Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted and area under the curve for the prediction model was compared with those of general severity scores measured in each of the cohorts. Two cutoff scores (one more sensitive for clinical trial design and one more specific for clinical practice and estimating resource utilization) were identified in the derivation cohort and were subsequently validated, with calculation of positive and negative likelihood ratios for both cut-off scores. Where appropriate, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NS, USA) was used in all data analyses.

Results

The primary outcome (death and/or ventilator dependence for longer than 14 days) occurred in 68% of patients in the international derivation cohort (VENTILA), in 60% of patients in the clinical trial validation cohort (ARDS-net), and in 59% of patients in the population-based validation cohort (KCLIP; Figure 1). Hospital mortality was 58% in VENTILA, 36% in ARDS-net, and 43% in KCLIP.

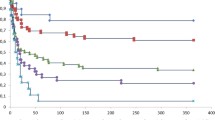

Table 1 shows the association of the predictor variables with death and/or ventilator dependence using univariate analyses in the derivation cohort. A simple logistic regression model (0.03 × age + 0.07 × day 3 oxygenation index + day 3 cardiovascular failure [1 if present, 0 if absent]) had moderate discriminative power and was well calibrated (Table 2, Figure 2 and Additional file 1).

Area under receiving operator curves: model versus day 1 SAPS II and day 3 SOFA scores. (a) International derivation cohort (VENTILA), (b) clinical trial validation cohort (ARDS-Net), and (c) population-based validation cohort (KCLIP). SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

In the clinical trial validation cohort, the model predicted death or ventilator dependence better than day 1 SAPS II and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores (P < 0.01; Figure 2). The discriminative power and calibration were good (Table 2). In the population-based validation cohort, the model was less well calibrated and performed similar to day 1 SAPS II score (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Both more sensitive (>3.0) and more specific (>3.5) cutoff scores for the model were identified in the derivation cohort and subsequently validated in the two validation cohorts (Table 3). Positive and negative likelihood ratios for different cutoff points of the model and for day 3 values of oxygenation index and PaO2/FiO2 ratio are presented in Table 3. Missing data precluded calculation of oxygenation index in 16% of patients in the derivation (VENTILA) cohort, 25% in the ARDS-net cohort, and 35% in the KCLIP cohort, and these patients were excluded from the analysis.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of three recent, large cohorts of patients with ALI, we observed that two-thirds of patients who were alive and invasively ventilated on day 3 after endotracheal intubation reached the composite outcome of death and/or ventilator dependence for more than two weeks. A simple model derived from age and cardiopulmonary function three days after intubation predicted death and/or ventilator dependence quite well in patients who were cared for in academic centers and enrolled in one of the ARDS-net trials. The model performance was acceptable, but not as strong when applied to the US population based cohort.

Altered lung mechanics and abnormal gas exchange are hallmarks of impaired lung function in ALI and are of prognostic significance [3]. Most models for quantifying gas exchange in a clinical setting consider the lungs as having three compartments: a shunt compartment, a dead space compartment, and normal lung. The size of the shunt compartment is commonly estimated by the PaO2/FiO2 ratio, whereas that of the dead space compartment scales with dead space ventilation (Vd/Vt) [3] and VE40 [6]. Both parameters are exquisitely sensitive to cardiac output and ventilator management. To adjust for the latter and to account for abnormal respiratory mechanics, clinicians at times derive an oxygenation index, which is defined as the PaO2/FiO2 ratio normalized by mean airway pressure. Oxygenation index has been associated with outcome in both adults and children with ALI [7, 8]. Apart from oxygenation index, other parameters relating to the ventilator (PEEP and plateau pressure) or gas exchange (PaCO2 and VE40) did not significantly contribute to the discriminative power of our model.

The presence of persistent shock, renal failure, age, immunosuppression, underlying cause of ALI, and overall severity of illness were previously identified as important nonpulmonary outcome determinants [1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 21, 22]. In the ARDS-net low tidal volume study [14], age, APACHE II score, plateau pressure, the number of organ failures (using the Brussels Organ Failure Classification), number of hospital days before enrollment, and arterial-alveolar oxygen gradient were found to be independent prognostic factors, and were used in the mortality adjustments reported in the recent ARDS-net study [11]. Age by itself is known to be an important predictor of poor outcome in patients with ALI [23]. Except for age and day 3 cardiovascular failure, additional markers of nonpulmonary organ failures (creatinine, platelet count, bilirubin, and Glasgow Coma Scale score) did not contribute to the discriminative power of our model. A logistic model similar to ours and based on age and day 3 oxygenation impairment was found to be predictive of prolonged mechanical ventilation in burn patients [24].

Of note, our model had better discrimination in a clinical trial dataset than in the two observational cohorts. This suggests that unmeasured factors related to co-interventions such as ventilator management or weaning, end of life care, and co-morbidities may introduce heterogeneity in patients who meet ALI definition in observational studies. Nevertheless, the model discrimination did not worsen when it was evaluated in the real-world setting of a population-based cohort of patients.

One of the objectives of our prediction model was to aid in decision making and clinical trial design with regard to the timing of tracheostomy. In a recent clinical trial conducted by Rumbak and coworkers [25], patients randomly assigned to early tracheostomy not only had shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit length of stay but also markedly lower hospital mortality (31.7% versus 61.7%; P < 0.005). Although the authors did not specifically address how many of these patients met criteria for ALI, it is likely, based on the description of the patient population, that a significant number of patients did indeed have ALI. One of the main criticisms of this study included somewhat arbitrary prediction of the need for prolonged mechanical ventilation (APACHE II score > 25). We believe that our model could be used in future studies of early versus late tracheostomy in patients with ALI.

The principal limitations or our study stem from its retrospective design insofar as neither of the original studies were designed to answer our questions. It is possible that some variables that were not routinely collected, for example Vd/Vt or net fluid balance, might have added to the model. Missing data precluded calculation of the oxygen index and, therefore, of the model for a significant number of patients. Having missing data did not significantly influence the outcome in the derivation cohort (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.41). In the validation cohorts, missing data were associated with a lower risk for death or prolonged ventilation (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.78 in the ARDS-net sample; OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90 in the KCLIP sample). Although the design of our study does not allow us to state the reasons for the missing data, we speculate that patients in whom the data needed to calculate oxygenation index were lacking (mean airway pressure and FiO2/PaO2) may have been improving clinically and undergoing weaning attempts.

Although our choice of a combined outcome including death and prolonged mechanical ventilation as the primary outcome may be questioned, it is important to emphasize that the two may not be reliably differentiated during the first few days of mechanical ventilation. The distinction between patients who die and those who undergo prolonged mechanical ventilation could be related to the preferences of patients and physicians regarding withholding of prolonged ventilation and rehabilitation, bearing in mind the potential poor quality of life in the future that may result from such interventions. Among the patients who survive the first few days of mechanical ventilation, the mortality and prolonged mechanical ventilation may be viewed as different ends of the spectrum of poor prognosis in patients with ALI. Improvement in the accuracy of prediction in future prospective studies will require careful consideration not only of factors related to underling pulmonary and nonpulmonary organ dysfunction but also of the characteristics of individual practices, patient preferences, premorbid functional status, and, possibly, biomarkers of lung injury and systemic inflammation.

Conclusion

A majority of patients with ALI are at risk for death or prolonged mechanical ventilation. A model derived from age, oxygenation index, and cardiovascular failure three days after intubation predicts death or prolonged mechanical ventilation and may inform decisions regarding specific interventions such as tracheostomy, particularly in terms of clinical trial design. However, because of the retrospective design of the present study, a validation study is warranted in an independent sample of patients.

Key messages

-

A substantial number of patients with ALI reached the combined end-point of death in the hospital or prolonged mechanical ventilation.

-

A simple model consisting of age and cardiopulmonary function on day 3 of mechanical ventilation predicted death and/or prolonged mechanical ventilation in patients with ALI.

-

Performance of the prediction model was better in the population of patients enrolled in a clinical trial than in the community.

Abbreviations

- ALI:

-

acute lung injury

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- FiO:

-

fractional inspired oxygen

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PaCO:

-

arterial carbon dioxide tension

- PaCo:

-

arterial oxygen tension

- PEEP:

-

positive end-expiratory pressure

- SAPS:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- VE40:

-

minute volume needed to bring PaCO2 to 40 mmHg.

References

Brun-Buisson C, Minelli C, Bertolini G, Brazzi L, Pimentel J, Lewandowski K, Bion J, Romand JA, Villar J, Thorsteinsson A, et al.: Epidemiology and outcome of acute lung injury in European intensive care unitsResults from the ALIVE study. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 51-61. 10.1007/s00134-003-2022-6

Luhr OR, Karlsson M, Thorsteinsson A, Rylander C, Frostell CG: The impact of respiratory variables on mortality in non-ARDS and ARDS patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2000, 26: 508-517. 10.1007/s001340051197

Nuckton TJ, Alonso JA, Kallet RH, Daniel BM, Pittet J-F, Eisner MD, Matthay MA: Pulmonary dead-space fraction as a risk factor for death in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2002, 346: 1281-1286. 10.1056/NEJMoa012835

Estenssoro E, Gonzalez F, Laffaire E, Canales H, Saenz G, Reina R, Dubin A: Shock on admission day is the best predictor of prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest 2005, 127: 598-603. 10.1378/chest.127.2.598

Ely EW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M, Steinberg KP, Bernard GR, for the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network: Recovery rate and prognosis in older persons who develop acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2002, 136: 25-36.

Jabour ER, Rabil DM, Truwit JD, Rochester DF: Evaluation of a new weaning index based on ventilatory endurance and the efficiency of gas exchange. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991, 144: 531-537.

Monchi M, Bellenfant F, Cariou A, Joly L-M, Thebert D, Laurent I, Dhainaut J-F, Brunet F: Early predictive factors of survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. A multivariate analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 158: 1076-1081.

Trachsel D, McCrindle BW, Nakagawa S, Bohn D: Oxygenation index predicts outcome in children with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 172: 206-211. 10.1164/rccm.200405-625OC

Walsh TS, Dodds S, McArdle F: Evaluation of simple criteria to predict successful weaning from mechanical ventilation in intensive care patients. Br J Anaesth 2004, 92: 793-799. 10.1093/bja/aeh139

Ware LB: Prognostic determinants of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults: impact on clinical trial design. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: S217-S222. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000155788.39101.7E

The National Heart L, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network: Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2004, 351: 327-336. 10.1056/NEJMoa032193

Bone R, Maunder R, Slotman G, Silverman H, Hyers T, Kerstein M, Ursprung J: An early test of survival in patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. The PaO 2 /FIO 2 ratio and its differential response to conventional therapy. Prostaglandin E1 Study Group. Chest 1989, 96: 849-851.

Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, Alia I, Brochard L, Stewart TE, Benito S, Epstein SK, Apezteguia C, Nightingale P, et al.: Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA 2002, 287: 345-355. 10.1001/jama.287.3.345

The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network: Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000, 342: 1301-1308. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801

Anonymous: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of lisofylline for early treatment of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 1-6. 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00001

Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD: Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2005, 353: 1685-1693. 10.1056/NEJMoa050333

Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R: The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 149: 818-824.

Moreno R, Morais P: Outcome prediction in intensive care: results of a prospective, multicentre, Portuguese study. Intensive Care Med 1997, 23: 177-186. 10.1007/s001340050313

Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Melot C, Vincent JL: Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA 2001, 286: 1754-1758. 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754

Hosmer D, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd edition. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2000.

Afessa B, Hogans L, Murphy R: Predicting 3-day and 7-day outcomes of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest 1999, 116: 456-461. 10.1378/chest.116.2.456

Aboussouan LS, Lattin CD, Anne VV: Determinants of time-to-weaning in a specialized respiratory care unit. Chest 2005, 128: 3117-3126. 10.1378/chest.128.5.3117

Ely EW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M, Steinberg KP, Bernard GR: Recovery rate and prognosis in older persons who develop acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2002, 136: 25-36.

Sellers BJ, Davis BL, Larkin PW, Morris SE, Saffle JR: Early prediction of prolonged ventilator dependence in thermally injured patients. J Trauma 1997, 43: 899-903.

Rumbak MJ, Newton M, Truncale T, Schwartz SW, Adams JW, Hazard PB: A prospective, randomized, study comparing early percutaneous dilational tracheotomy to prolonged translaryngeal intubation (delayed tracheotomy) in critically ill medical patients. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1689-1694. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000134835.05161.B6

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by NHLBI K23 HL78743-01A1. For a list of the Second International Study of Mechanical Ventilation and ARDS-net investigators please see Additional file 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

OG, BA, RDH, GDR, and FF-V contributed to the study design, and data analysis and interpretation. OG, BTT, GDR, FF-V, AA, and AE contributed to the data collection and interpretation. MM contributed to data analysis and interpretation.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2007_5391_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: A Word document providing additional statistical details and summarizing the investigators who participated in VENTILA (Second International Study of Mechanical Ventilation), by country and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) ARDS Clinical Trials Network. (DOC 118 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Gajic, O., Afessa, B., Thompson, B.T. et al. Prediction of death and prolonged mechanical ventilation in acute lung injury. Crit Care 11, R53 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc5909

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc5909