Abstract

Experimental studies in ischemia–reperfusion and sepsis indicate that activated protein C (APC) has direct anti-inflammatory effects at a cellular level. In vivo, however, the mechanisms of action have not been characterized thus far. Intravital multifluorescence microscopy represents an elegant way of studying the effect of APC on endotoxin-induced leukocyte–endothelial-cell interaction and nutritive capillary perfusion failure. These studies have clarified that APC effectively reduces leukocyte rolling and leukocyte firm adhesion in systemic endotoxemia. Protection from leukocytic inflammation is probably mediated by a modulation of adhesion molecule expression on the surface of leukocytes and endothelial cells. Of interest, the action of APC and antithrombin in endotoxin-induced leukocyte–endothelial-cell interaction differs in that APC inhibits both rolling and subsequent firm adhesion, whereas antithrombin exclusively reduces the firm adhesion step. The biological significance of this differential regulation of inflammation remains unclear, since both proteins are capable of reducing sepsis-induced capillary perfusion failure. To elucidate whether the action of APC and antithrombin is mediated by inhibition of thrombin, the specific thrombin inhibitor hirudin has been examined in a sepsis microcirculation model. Strikingly, hirudin was not capable of protecting from sepsis-induced microcirculatory dysfunction, but induced a further increase of leukocyte–endothelial-cell interactions and aggravated capillary perfusion failure when compared with nontreated controls. Thus, the action of APC on the microcirculatory level in systemic endotoxemia is unlikely to be caused by a thrombin inhibition-associated anticoagulatory action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alongside antithrombin and C1-esterase inhibitor, activated protein C (APC) represents an important coagulatory inhibitor in humans [1]. The zymogen protein C is activated by the thrombin–thrombomodulin complex to give APC, whose anticoagulatory activity is conferred primarily by its ability to inactivate Factor Va and VIIIa [2]. APC is also known to increase fibrinolysis [3]. In human sepsis, disruption of the normal balance between coagulation and fibrinolysis has been characterized by its correlation with organ dysfunction and increased mortality [1, 4]. Thus, acquired protein C deficiency is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock [5, 6].

Direct anti-inflammatory properties of APC that have been characterized in vitro were considered independent from coagulatory inhibition [7–9]. Thus, an experimental APC application is capable of blocking the lethal effects of Escherichia coli-induced septic disseminated intravascular coagulation [10], but also improves outcome in meningococcal-induced septic shock [11]. Also, APC effectively prevents endotoxin-induced pulmonary vascular injury [12]. Conversely, the application of antiprotein-C antibodies produces higher sensitivity towards defined endotoxin stimuli and increases mortality [12]. Because organ dysfunction and animal survival are not improved by the administration of other substances with comparable anticoagulant effects, it has been suggested that the action of APC is not solely dependent upon its anticoagulatory properties [12]. Although there is in vitro evidence from cell-culture studies to show that APC blocks leukocytic adhesion to the endothelium [13], the in vivo mechanisms of APC-related anti-inflammatory and microcirculatory action have not been completely elucidated thus far.

Before discussing the role of APC on the microcirculation in sepsis, we will provide some information on the role of the microcirculation in the development of organ dysfunction and coagulatory failure.

Role of leukocyte–endothelial-cell interactions and capillary perfusion failure in the development of septic organ failure and coagulatory failure

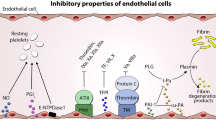

Leukocyte–endothelial-cell interaction is essential for an effective defense against bacterial invasion [14]. However, leukocytic activation is associated with an increased proinflammatory immune response [15], which is caused by an increased release of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β and interleukin-8, which initiate generalized neutrophil (polymorphonucleocyte) activation [16]. This release of mediators, together with the generalized activation and sequestration of neutrophils, may contribute to the widespread microvascular injury and subsequent endothelial damage observed in sepsis [17]. The migration of polymorphonucleocytes to inflamed tissue is primarily dependent on the induction of secondary adhesion molecules that are expressed on leukocytes and activated vascular endothelium [18, 19]. This migration, along with the subsequent release of oxygen radicals and other toxic substances, represents a central step in the development of multiple organ failure [20].

The endothelial switch from anticoagulant to procoagulant during sepsis is thought to be related to the cytokine-mediated expression of endothelial adhesion molecules (e.g. E-selectin, P-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1) [21] and increased tissue factor production by monocytes and endothelial cells [22]. Generalized activation of coagulation can be quantified by the measurement of endogenous coagulatory inhibitors. Additionally, endotoxins are, per se, known to directly generate an environment favoring coagulation processes by activating the extrinsic coagulation pathway via monocytic tissue factor expression [23]. Thus, the concept of exogenous application of natural coagulatory inhibitors has been evaluated in terms of reducing systemic activation of leukocytes and endothelial cells [9, 24].

Action of APC on the microcirculation in ischemia–reperfusion injury

Although the anticoagulatory effects of APC have been extensively investigated during the last two decades, only a few studies have analyzed the actions of APC on the microcirculation during ischemia–reperfusion. To study ischemia–reperfusion injury in a clinically relevant setting, models of warm ischemia have been extensively used in rodents. In a rat model, APC has been administered intravenously before the induction of warm ischemia [25]. Interestingly, the histological changes in renal tissue observed in control animals after noncrushing microvascular clamping for 60 min were almost completely absent after prophylactic APC administration in this model. These APC effects on organ structure corresponded to a highly effective preservation of renal tissue blood flow that was significantly decreased after ischemia–reperfusion in controls. Also, changes in vascular permeability were prevented effectively by APC application [25]. Since these postischemic alterations were only significantly inhibited by APC and not a specific Factor Xa inhibitor or heparin, the authors suggested that APC protects against ischemia–reperfusion-induced renal injury not by inhibition of coagulation abnormalities but rather by direct inhibition of leukocyte activation.

Another group has also described a combination of anti-inflammatory and anticoagulatory actions of APC during renal ischemia reperfusion that provided microvascular protection [26]. In this model, leukopenia effectively reduced ischemia–reperfusion-induced renal injury. Since leukocytes were, therefore, thought to be of central importance in the development of organ injury, the authors hypothesized that APC inhibits neutrophil adhesion, thereby attenuating the release of neutrophil elastase and oxygen radicals, both of which increase vascular permeability. However, since neither group had the opportunity to evaluate the actions of APC on the microcirculation in vivo, their conclusions remain speculative.

The effects of APC on ischemia–reperfusion-induced organ damage have also been evaluated in hepatic tissue: Yamaguchi and colleagues investigated the role of APC in a model of ischemia–reperfusion-induced injury in rat livers [27]. Before inducing liver ischemia by portal vein cross-clamping for 30 min, APC was intravenously applied. The serum concentrations of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractants (CINC) were significantly reduced by APC application. Simultaneously, an observed lowering of myeloperoxidase activity in hepatic tissue during APC application indicated a lesser accumulation of neutrophils in the liver. Of interest, an inactive derivative of Factor Xa, which represents a selective inhibitor of thrombin generation, was also effective in decreasing CINC concentrations and could prevent leukocyte accumulation. This indicated that, in this case, postischemic hepatic microcirculatory disturbances were induced by microthrombotic occlusion in a thrombin-dependent mechanism.

Action of APC on the microcirculation during endotoxemia

APC has been used in several sepsis models to modulate the sepsis-induced proinflammatory response. Thus, a prospective, blinded, placebo-controlled trial has been performed in a rabbit model of meningococcal endotoxin-induced shock [11]. APC was administered as a continuous infusion to prevent sepsis-induced cardiocirculatory failure. Strikingly, APC administration could not prevent an endotoxin-mediated decrease in mean arterial pressure and an increase in heart rate. However, despite lacking any effect on macrohemodynamics, survival was significantly improved from 45% to 75%. The authors hypothesized that APC had an effect on the microcirculation since the expected macrohemodynamic changes could not be characterized in their experiment. In a model of endotoxin-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome, APC attenuated endotoxin-induced pulmonary vascular injury, probably by the significant reduction of endotoxin-induced pulmonary leukocyte infiltration [12]. In light of these findings, it is highly likely that APC also has a direct effect on the microcirculation during endotoxemia. However, none of these models allowed the direct visualization of the microcirculation and, thus, the study of APC effects on microcirculatory dysfunction.

To evaluate the effects of APC on the microcirculation in vivo during endotoxemia, our group tested APC in a sepsis model that permitted observation of the microcirculation under non-invasive, normotensive conditions [28]. Endotoxin induced a massive increase in leukocyte accumulation in precapillary arterioles and postcapillary venules, with a maximal effect observed after 8 hours (Fig. 1). Macrohemodynamic disturbances could be excluded by careful analysis of macrohemodynamic and microhemodynamic parameters in this model [29]. APC significantly reduced endotoxin-induced leukocyte rolling in arterioles and venules (Fig. 2). Moreover, the next step in the leukocyte–endothelial-cell interaction (namely, leukocyte adherence) was also significantly inhibited in arterioles and venules (Fig. 3) [30]. In addition, endotoxin-mediated deterioration of microvascular perfusion was counteracted effectively by intravenous APC administration. Since leukocyte rolling is predominantly mediated by adhesion molecules of the selectin family, the reduction of leukocyte rolling by APC may indicate a modulation of selectin expression on leukocytes and the endothelium.

Visualization of leukocyte sticking in the arteriole by intravital fluorescence microscopy (performed using a charge-coupled device camera before and after lipopolysaccharide administration). Representative arterioles (a) before and (b) 8 hours after endotoxin application. Note that leukocytes also adhere to the endothelial lining of arterioles during endotoxemia despite high flow conditions.

Effect of activated protein C (APC) on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced (a) arteriolar and (b) venular leukocyte rolling. The APC group contained animals (n = 8) that received LPS (2 mg/kg) and APC (24 μg/kg per 8 hours intravenously). The control group contained vehicle-treated animals (n = 7) that received LPS (2 mg/kg) only. *P < 0.05, APC animals versus lipopolysaccharide-treated controls (unpaired Student's t-test). §P < 0.05, intergroup differences from baseline (paired Student's t-test). Data are the mean ± standard error of mean. Reproduced with permission [30].

Effect of activated protein C (APC) on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced (a) arteriolar and (b) venular leukocyte adhesion. The APC group contained animals (n = 8) that received LPS (2 mg/kg) and APC (24 μg/kg per 8 hours intravenously). The control group contained vehicle-treated animals (n = 7) that received LPS (2 mg/kg) only. *P < 0.05, APC animals versus lipopolysaccharide-treated controls (unpaired Student's t-test). §P < 0.05, intergroup differences from baseline (paired Student's t-test). Data are the mean ± standard error of mean. Reproduced with permission [30].

This view corresponds to in vitro data obtained by vascular endothelial cell culturing, where human plasma-derived and human cell-produced protein C blocked E-selectin-mediated cell adhesion to the endothelium [13]. From our in vivo study, we concluded that it is highly likely that a specific anti-inflammatory interaction between APC and the endothelium is responsible for microcirculatory protection. Since thrombin inhibition alone obviously does not reduce endotoxin-mediated leukocyte rolling and adhesion [31], anticoagulatory APC activities (namely, inhibition of Factors Va and VIIIa that would result in less thrombin formation) are probably unlikely to be responsible for the protective effects of APC on the microcirculation during endotoxemia. Table 1 shows an overview of the differential effects of the anticoagulants APC, antithrombin, and hirudin (a specific thrombin inhibitor) on different steps in the leukocyte–endothelial-cell interaction and capillary perfusion in septic disorders.

Conclusion

The protein C and antithrombin anticoagulant pathways represent major mechanisms in controlling microvascular dysfunction during ischemia–reperfusion injury and sepsis. Local and systemic antithrombin and APC deficiencies augment the proinflammatory response and thereby contribute to increased leukocyte–endothelial-cell interactions and capillary perfusion failure. The obvious reduction in endogenous inhibitors represents the rationale for exogenous coagulatory inhibitor treatment. APC and antithrombin have been used in experimental models to reduce ischemia–reperfusion injury and to improve septic disorders with comparable efficacy. The exact molecular mechanisms of action of APC and antithrombin during ischemia–reperfusion and endotoxemia remain unclear. However, it is highly likely that a specific anti-inflammatory interaction with the endothelium and leukocytes is responsible for APC-related microcirculatory protection. Thus, APC treatment using a dose corresponding to that used in the Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study in vivo reduced the extent of transient leukocyte–endothelial-cell interactions (leukocyte rolling) and inhibited subsequent firm leukocyte adherence (leukocyte sticking) to the endothelium. Both mechanisms lessened endotoxin-mediated microvascular perfusion injury. These microcirculatory APC actions may also be used under clinical situations involving microcirculatory disorders. From the majority of experimental studies presented here, there is, however, no evidence to support antithrombotic (anticoagulatory) therapy specifically targeting thrombin inhibition, since thrombin inhibitors (e.g. hirudin and heparin) do not provide comparable protection of the microcirculation, but, on the contrary, may even aggravate sepsis-mediated disorders.

Abbreviations

- APC:

-

activated protein C

- CINC:

-

cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractants

- PROWESS:

-

Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis.

References

Bone RC: Modulators of coagulation. A critical appraisal of their role in sepsis. Arch Intern Med 1992, 152: 1381-1389. 10.1001/archinte.152.7.1381

Yan SB: Activated protein C versus protein C in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: S69-S74. 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00024

Krishnamurti C, Young GD, Barr CF, Colleton CA, Alving BM: Enhancement of tissue plasmin activator-induced fibrinolysis by activated protein C in endotoxin-treated rabbits. J Lab Clin Med 1991, 118: 523-530.

Hoffmann JN, Mühlbayer D, Jochum M, Inthorn D: Effect of long-term and high-dose antithrombin supplementation on coagulation and fibrinolysis in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1851-1859. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000139691.54108.1F

Fourrier F, Chopin C, Goudemand J, Hendrycx S, Caron C, Rime A, Marey A, Lestavel P: Septic shock, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Compared patterns of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S deficiencies. Chest 1992, 101: 816-823.

Mesters RM, Helterbrand JD, Utterback BG, Yan SB, Chao YB, Fernandez JA, Griffin JH, Hartmann DL: Prognostic value of protein C concentrations in neutropenic patients at risk of severe septic complications. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 2209-2216. 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00005

Grey ST, Tsuchida A, Hau H, Orthner CL, Salem HH, Hancock WW: Selective inhibitory effects of the anticoagulant activated protein C on the responses of human mononuclear phagocytes to LPS, IFN gamma, or phorbol ester. J Immunol 1994, 153: 3664-3672.

White B, Schmidt M, Murphy C, Livingstone W, O'Toole D, Lawler M, Neill L, Kelleher D, Schwarz HP, Smith OP: Activated protein C inhibits lipopolysaccharide induced nuclear translocation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) production in the THP-1 monocytic cell line. Br J Haematol 2000, 110: 130-134. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02128.x

Esmon CT: Introduction: are natural anticoagulants candidates for modulating the inflammatory response to endotoxin? Blood 2000, 95: 1113-1116.

Taylor FBJ, Chang A, Esmon CT, D'Angelo A, Vigano DA, Blick KE: Protein C prevents the coagulopathic and lethal effects of Escherichia coli infusion in the baboon. J Clin Invest 1987, 79: 918-925.

Roback MG, Stack AM, Thompson C, Brugnara C, Schwarz HP, Saladino RA: Activated protein C concentrate for the treatment of meningococcal endotoxin shock in rabbits. Shock 1998, 9: 138-142.

Murakami K, Okajima K, Uchiba M: Activated protein C attenuates endotoxin-induced pulmonary vascular injury by inhibiting activated leucocytes in rats. Blood 1996, 87: 642-647.

Grinnell BW, Herman RB, Yan SB: Human protein C inhibits selectin-mediated cell adhesion: role of unique fucosylated oligosaccharid. Glycobiology 1994, 4: 221-224.

Butcher EC: Leucocyte–endothelial cell recognition – three or more steps to specificity and diversity. Cell 1991, 67: 1033-1036. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90279-8

Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE: The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 348: 138-150. 10.1056/NEJMra021333

de Backer D, Creteur J, Pricer JC, Dubois MJ, Vincent JL: Microvascular blood flow is altered in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166: 98-104. 10.1164/rccm.200109-016OC

Lam C, Tymi K, Martin C, Sibbald W: Microvascular perfusion is impaired in a rat model of normotensive sepsis. J Clin Invest 1994, 94: 2077-2083.

Kishimoto TK, Larson RS, Corbi AL, Dustin ML, Staunton DE, Springer TA: The leucocyte integrins. Adv Immunol 1989, 46: 149-182.

Rothlein R, Wegner C: Role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in the inflammatory response. Kidney Int 1992, 41: 617-619.

McCuskey R, Urbaschek R, Urbaschek B: The microcirculation during endotoxinemia. Cardiovasc Res 1996, 32: 752-763. 10.1016/0008-6363(96)00113-7

Strieter RM, Kunkel SL: Acute lung injury: the role of cytokines in the elicitation of neutrophils. J Investig Med 1994, 42: 640-651.

Park CT, Creasey AA, Wright SD: Tissue factor pathway inhibitor blocks cellular effects of endotoxin by binding to endotoxin and interfering with transfer to CD 14. Blood 1997, 89: 4268-4274.

Johnston B, Walter UM, Issekutz AC, Issekutz TB, Anderson DC, Kubes P: Differential roles of selectins and the alpha4-integrin in acute, subacute, and chronic leucocyte recruitment in vivo . J Immunol 1997, 159: 4514-4523.

Hoffmann JN, Faist E: Coagulation inhibitor replacement during sepsis: useless? Crit Care Med 2000, 28: S74-S76. 10.1097/00003246-200009001-00016

Mizutani A, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Noguchi T: Activated protein C reduces ischemia/reperfusion-induced renal injury in rats by inhibiting leucocyte activation. Blood 2000, 95: 3781-3787.

Schoots IG, Levi M, van Vliet AK, Maas AM, Rossink EH, van Gulik TM: Inhibition of coagulation and inflammation by activated protein C or antithrombin reduces intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1375-1383. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000128567.57761.E9

Yamaguchi Y, Hisama N, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Murakami K, Takahashi Y, Yamada S, Mori K, Ogawa M: Pretreatment with activated protein C or active human urinary thrombomodulin attenuates the production of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant following ischemia reperfusion. Hepatology 1997, 25: 1136-1140. 10.1002/hep.510250515

Hoffmann JN, Vollmar B, Inthorn D, Schildberg FW, Menger MD: A chronic model for intravital microscopic study of microcirculatory disorders and leucocyte/endothelial cell interaction during normotensive endotoxinemia. Shock 1999, 12: 355-364.

Hoffmann JN, Vollmar B, Laschke M, Inthorn D, Schildberg FW, Menger MD: Hydroxyethyl starch (130 kD) but not crystalloid volume support improves microcirculation during normotensive endotoxemia. Anesthesiology 2002, 97: 460-470. 10.1097/00000542-200208000-00025

Hoffmann JN, Vollmar B, Laschke M, Inthorn D, Fertmann J, Schildberg FW, Menger MD: Microhemodynamic and cellular mechanisms of activated protein C action during endotoxemia. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1011-1017. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000120058.88975.42

Hoffmann JN, Vollmar B, Inthorn D, Schildberg FW, Menger MD: The thrombin antagonist hirudin fails to inhibit endotoxin-induced leucocyte/endothelial cell interaction and microvascular perfusion failure. Shock 2000, 14: 528-534.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

JNH received reimbursements for oral presentations from Eli Lilly and Company and ZLB Behring.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffmann, J.N., Vollmar, B., Laschke, M.W. et al. Microcirculatory alterations in ischemia–reperfusion injury and sepsis: effects of activated protein C and thrombin inhibition. Crit Care 9 (Suppl 4), S33 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc3758

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc3758