Abstract

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a physiological form of cell death that is important for normal embryologic development and cell turnover in adult organisms. Cumulative evidence suggests that apoptosis can also be triggered in tissues without a high rate of cell turnover, including those within the central nervous system (CNS). In fact, a crucial role for apoptosis in delayed neuronal loss after both acute and chronic CNS injury is emerging. In the current review we summarize the growing evidence that apoptosis occurs after traumatic brain injury (TBI), from experimental models to humans. This includes the identification of apoptosis after TBI, initiators of apoptosis, key modulators of apoptosis such as the Bcl-2 family, key executioners of apoptosis such as the caspase family, final pathways of apoptosis, and potential therapeutic interventions for blocking neuronal apoptosis after TBI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Each year in the USA, more than 1 million patients undergo medical evaluation and treatment for acute head injury [1]. In the USA there were an average of 53,288 annual traumatic brain injury (TBI)-related deaths from 1989 to 1998, or 19.3 per 10,000 [2]. In Germany, the TBI death rate in 1996 was 11.5 per 10,000, with a total of 9415 deaths [3]. A 15-year study in Denmark showed that the mortality of children after TBI was 22%, and among those survivors of severe head injury, significant numbers were found to have serious neurological disabilities [4]. A regional population-based study in France showed that the mortality of hospitalized TBI patients was as high as 30.0% [5]. Similar data can be found in studies from a variety of demographic and cultural settings [6, 7]. Acute and long-term care of TBI patients has become a significant social and economic burden around the world [8–10].

The neurological outcome of TBI victims depends on the extent of the primary brain insult caused by trauma itself, and on the secondary neurochemical and pathophysiological changes occurring as a consequence of the mechanical injury, which leads to additional neuronal cell loss. Although a long list of experimental studies suggest that reduction or prevention of secondary brain injury after TBI is possible, clinical trials have failed to show benefit from therapeutic strategies proven to be effective in the laboratory [11–13]. This might reflect the diverse nature of clinical TBI and/or perhaps an incomplete understanding of the mechanisms of secondary neuronal loss.

Two waves of neuronal cell death occur after TBI. Immediately after mechanical trauma due to impact or penetration, neurons can die by necrosis caused by membrane disruption, irreversible metabolic disturbances and/or excitotoxicity [14]. Early application of neuroprotective protocols seems critical for any possibility of reducing neuronal necrosis; however, this is beyond the scope of the current review. The second wave of neuronal death occurs in a more delayed fashion, with morphological features of apoptosis (or programmed cell death). This second wave of neuronal cell death presents within a time window that may be responsive to targeted therapies [15]. The current review summarizes clinically related investigation of apoptosis after TBI, as well as potential therapeutic interventions for altering apoptosis to improve neurological outcome.

Apoptosis: historical overview

Apoptosis has long been identified as an evolutionarily conserved process of active cell elimination during development. Its phenotypic features include DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation, cell shrinkage, and formation of apoptotic bodies, which are cleared by phagocytosis without initiating a systemic inflammatory response. The execution of apoptosis requires novel gene expression and protein synthesis [16–18]. Apoptosis has evolved as an intricate and critical mechanism for balancing cell proliferation and for the active remodeling of tissues during development.

The identification of apoptosis under pathological settings dates back to the 1960s, when John FR Kerr was studying ischemic liver damage [19]. He observed a novel cell death phenotype that was morphologically distinct from classical necrosis. Dying hepatocytes in the ischemic penumbra were found to have shrunk to form small round masses of cytoplasm containing condensed nuclear chromatin. These dying cells were taken up by neighboring hepatocytes and phagocytes without initiating a broader inflammatory response. This phenomenon was also recognized in normal rat livers. This distinct type of cell death, temporarily named 'shrinkage necrosis' [20], was also found to occur in cancer [21] and during normal development [22]. The term 'apoptosis' was subsequently coined to replace shrinkage necrosis [23], and has later been used interchangeably with programmed cell death, albeit loosely, because of similar requirements for genetic programming and new protein synthesis, as well as morphological similarities [24].

The identification of post-developmental apoptosis in Huntington's disease opened a new avenue of research in acute and chronic neurological diseases [25]. Although histological descriptions of apoptosis after experimental TBI [26] were reported in the same era as the seminal reports by Kerr and colleagues noted above, the characterization of neuronal apoptosis after experimental TBI occurred less than a decade ago [27–29]. Histological descriptions of apoptosis after human head injury [30, 31] actually predate those by Kerr and colleagues, but similarly to experimental studies, characterization of apoptosis after TBI in humans has occurred only recently [32].

Pathways of apoptosis

The endpoint of neuronal apoptosis after brain injury is the systematic fragmentation of cellular DNA and the collapse of nuclear structure, followed by the formation of membrane-wrapped apoptotic bodies [29, 33] that are subsequently cleared by macrophages/microglia signaled by phosphatidylserine exposure on the cell membrane surface [34]. The process of apoptosis can occur by multiple pathways that may be independent; however, crosstalk between these pathways can also occur [15] (Fig. 1). In broad terms, neuronal apoptosis can at present be segregated into two pathways, one involving the activation of a family of cysteine proteases termed 'caspases', and one involving the caspase-independent release of apoptotic factors from mitochondria [35].

Simplified schematic representation of the initiation and regulation of neuronal apoptosis after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Pathologic mechanisms triggering apoptosis after TBI include ischemia, oxidative stress, energy failure, excitotoxicity (primarily excess glutamate), axonal injury, trophic factor withdrawal, ER stress, and/or death receptor-ligand binding (for example TNF, Fas). Regulation of apoptosis occurs through multiple pathways including kinase-dependent intracellular signaling pathways and Bcl-2 family proteins. Execution of apoptosis involves the caspase cascade and/or release of apoptogenic factors from organelles such as mitochondria and lysosomes. Ultimately DNA fragmentation, cytoskeletal disintegration, and externalization of membrane phosphatidylserine occurs, signaling macrophages and microglia to engulf cellular debris. Potential therapeutic targets discussed in this review are highlighted within the dashed yellow lines. AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; Apaf-1, apoptotic protease activating factor-1; Bcl, B-cell lymphoma; CAD, caspase-activated deoxyribonuclease; casp, caspase; cyto c, cytochrome c; DISC, death-inducing signaling complex; Endo G, endonuclease G; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; iCAD, inhibitor of CAD; ROS, reactive oxygen species; tBid, truncated Bid; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR, TNF receptor; TRAF2, TNF receptor associated factor.

Caspase-dependent apoptosis

Caspase family proteases include 14 currently identified members that are synthesized as pro-enzymes [36]. After proteolytic cleavage into large and small subunits, they are capable of forming active tetrameric proteases [37]. Initiator caspases, including caspase-8, -9, and -10, are activated by auto-cleavage and aggregation. Caspase-3, -6, and -7, referred to as 'executioner' caspases, are cleaved and activated by initiator caspases. The proteolytic cleavage of caspase substrates produces the phenotypic changes characteristic of apoptosis, including cytoskeletal disintegration, DNA fragmentation, and disruption of cellular and DNA repair processes, all of which have been reported after experimental TBI [38–40].

Caspase-dependent apoptosis can occur via extrinsic or intrinsic pathways. Extrinsic pathways involve cell surface receptors present on multiple cell types including neurons [41]. The coupling of cell surface tumor necrosis factor (TNF) with extracelluar TNF or Fas receptors with extracellular Fas ligand induces trimerization of the receptors that form complexes with intracellular signaling molecules: TNF receptor associated death domain protein and Fas-associated protein with death domain. This death-inducing signaling complex then binds and induces the auto-cleavage and activation of caspase-8 [42] or caspase-10 [43]. Caspase-3 is subsequently cleaved and activated by these initiator caspases, whereupon the process of apoptosis is irreversible.

The intrinsic pathway is initiated by stress on cellular organelles, including mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Caspase-dependent apoptosis can be triggered by the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c induced after mitochondrial membrane depolarization and formation of mitochondrial permeability transition pores. Cytosolic cytochrome c interacts with apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), ATP, and pro-caspase-9 to form a complex termed an 'apoptosome'. Apaf-1, a mammalian homologue of the Caenorhabditis elegans gene product CED-4, contains a caspase recruitment domain that binds pro-caspase-9. The multiple WD-40 repeats in Apaf-1 permit self-oligomerization and auto-activation of caspase-9, which in turn cleaves and activates caspase-3 [44]. Recent data indicate that after being released from mitochondria, cytochrome c can translocate to the ER to block the inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor, amplifying calcium signaling and the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria [45]. ER stress, including the disruption of ER calcium homeostasis and accumulation of excess proteins, induce apoptosis by the activation of ER-localized caspase-12. The ER-stress-related activation of caspase-12 has been detected in experimental models of neurodegenerative disease [46] and TBI [47], although in humans caspase-12 seems to have a role in inflammation but not in apoptosis [48, 49].

Other important enzyme families also contribute to apoptotic cell death after brain injury. Calpains are calcium-dependent proteases with many cellular targets including cytoskeletal elements. Calpain activation occurs after TBI and colocalizes with caspase-3 cleavage [39, 50]. Calpain inhibitors have been shown to reduce neuropathological damage after TBI in rats [51, 52]. The lysosomal enzymes, cathepsins, might also contribute to apoptotic cell death after brain injury [53], although studies showing a prominent role for cathepsins after TBI are lacking.

Caspase-independent apoptosis

Several mitochondrial proteins are capable of inducing apoptosis without activation of caspases, or without being affected by caspase inhibition. Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) is an evolutionarily conserved mitochondrial flavoprotein that can be released from mitochondria after mitochondrial membrane depolarization [54]. The subsequent translocation of AIF into the nuclei induces the formation of large-scale DNA fragmentation (more than 50 kilobase pairs), a signature event of AIF-mediated cell death. AIF-mediated apoptosis occurs in neurons under conditions of oxidative stress [55], as well as in experimental TBI [56] and brain ischemia [57]in vivo. Other apoptosis-related mitochondrial proteins include endonuclease G [58], Htr2A/Omi [59], and Smac/Diablo [60]; however, their roles in neuronal apoptosis after brain injury remain undefined. Studies [59, 61, 62] showing powerful detrimental effects of mitochondrially released proteins with important intramitochondrial functions illustrate the importance of cellular compartmentalization.

It was recently discovered that poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activation, previously felt to contribute solely to necrotic cell death, could also contribute to caspase-independent apoptosis [55, 63]. Under conditions of severe injury, depletion of cellular NAD+ via PARP activation exacerbates energy failure, resulting in membrane leakage and necrosis [64]. However, under conditions of incomplete energy failure, as can be seen in pericontusional regions in models of TBI, PARP activation can contribute to mitochondrial depolarization, AIF release, and apoptosis [55, 56]. Thus, PARP inhibitors represent a therapeutic strategy targeting both necrosis, if administered early enough, and apoptosis after TBI [65].

Regulation of apoptosis

Both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis are regulated by the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family of proteins, which include both pro-death and pro-survival members [66]. Bcl-2 family proteins regulate the permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane and permeability transition pore formation [67]. They contain highly conserved Bcl-2 homology domains (BH 1–4) essential for homo-complex and heterocomplex formation [66]. Complexes formed between proteins containing BH-3 domains such as Bax, truncated Bid, and Bad, can facilitate the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria [66]. Upregulation of Bax with subsequent mitochondrial translocation can be induced by the tumor suppressor p53, which is increased in injured regions after TBI in rats [68, 69]. The anti-apoptotic members Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1L prevent the release of mitochondrial proteins, including cytochrome c[70], endonuclease G [58], and AIF [54], by inhibiting the pore-forming function of BH-3 domain-containing Bcl-2 proteins [71]. Recent studies have identified the existence of crosstalk between the extrinsic and intrinsic cell death pathways by means of the BH3 domain-only protein Bid [72]. The anti-apoptotic gene bcl-2 and its protein product are upregulated in injured cortex and hippocampus after TBI in rats, and cells expressing Bcl-2 protein seem morphologically normal [73]. Data from human studies suggest that Bcl-2 family proteins might also participate in the regulation of the stress response by interacting with heat shock proteins [74].

Apoptosis can also be regulated by intracellular signal transduction pathways. Perturbations in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal-transduction pathways occur after TBI [75]. Several components of the MAPK pathway–extracellular regulated kinase-1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 pathways – are differentially activated depending on the region of brain and timing after injury [75, 76]. Activation of the protein kinase C signaling pathway has also been reported after experimental TBI [77]. Pro-survival intracellular signal transduction pathways are also activated after brain injury. These include activation of the growth factor-induced protein kinase B (PKB) signaling pathway, which can directly inhibit apoptosis through the phosphorylation and inactivation of apoptosis-related proteins Bad and caspases-8 and -9 [78]. Phosphorylation of PKB is not seen in cells that are positive for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) after TBI, providing indirect evidence that PKB inhibits cell death in vivo[79]. PKB might also promote cell survival through the regulation of nuclear factor-κB and gene expression related to cyclic-AMP response element binding [78].

Evidence for apoptosis in humans after traumatic brain injury

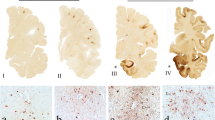

Although phenotypic descriptions of apoptosis after TBI in humans date back to the 1940s [30, 31], biochemical evidence of the reactivation of the apoptotic cascade after TBI in humans has been reported only within the past decade. Injured brain tissue samples obtained from TBI patients requiring decompressive craniectomy for the treatment of life-threatening intracranial hypertension were found to have evidence of DNA fragmentation by TUNEL and cleavage of caspase-1 and -3, suggesting activation of caspase-dependent apoptosis [32]. Activation of caspase-3 is also supported by studies demonstrating cellular alterations of one of its substrates, PARP, within brain tissue from TBI patients [80]. Recently, the upregulation of caspase-8 in human brain after TBI at both the transcriptional and translational levels has been reported [81]. In this study, caspase-8 was found predominantly in neurons. In addition, relative protein levels of both caspase-8 and cleaved caspase-8 correlated with relative protein levels of Fas death receptor, providing evidence of the formation of a death-inducing signaling complex and activation of the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis within neurons. Increases in Fas and Fas ligand have also been reported in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from TBI patients, with Fas levels correlating with intracranial pressure [82, 83]. Evidence for participation of the intrinsic pathway after TBI in humans also exists. Consistent with experimental TBI models is the observation that upregulation of Bcl-2 occurs in human brain from adults and in CSF from infants and children after TBI [32, 84]. In pediatric patients, lower concentrations of Bcl-2 were detected in patients that died than in those that survived, supporting a pro-survival role for Bcl-2 [84]. The pro-death Bcl-2 family protein Bax is also detectable in contused brain tissue in TBI patients. Patients with detectable Bax but not Bcl-2 had a less favorable outcome than patients in whom both Bax and Bcl-2 were detectable [85]. Although these studies demonstrate the acute initiation of apoptosis in human brain after injury, protracted apoptosis also occurs. TUNEL-positive cells have been detected in autopsy specimens from patients dying up to 12 months after their injury [86], perhaps suggesting that a relatively wide therapeutic window exists for the administration of treatments aimed at reducing apoptosis after TBI.

In human head injury, apoptotic neuronal cell death has been identified in the pericontusional gray matter [32, 81] and in oligodendrocytes within white matter [84]. In terms of defining brain regions where apoptosis occurs after TBI, these studies using biopsy tissue were limited by the focused location (lesion and perilesion area or non-dominant temporal lobe). However, autopsy studies also localize apoptotic, and TUNEL-positive, non-apopoptic cellular phenotypes, to the contusion or within close proximity to the contusion [87].

Parallels and differences between apoptosis after TBI and ischemia

Given the highly conserved nature of the apoptotic cascade, it is not surprising that there are several similarities in terms of initiation and reactivation of the apoptosis between acute brain injuries such as trauma and ischemia. In fact, all of the processes discussed above have been shown to occur in experimental models of both cerebral trauma and ischemia (reviewed by Liou et al. [15]). Similarities might also be related in part to the fact that the pathophysiology of trauma includes an ischemic component [88], although after trauma this usually involves hypoperfusion or 'trickle flow' rather than complete ischemia with reperfusion. One important difference seems to be related to the heterogeneity of the disease process in TBI compared with ischemia, in which in addition to hypoperfusion, conditions of contusion necrosis, excitotoxicity, axonal injury, and inflammation coexist (see Fig. 1). An important biochemical distinction might be an increased contribution of caspase-independent apoptosis after TBI in comparison with ischemia. A spectrum of cell death phenotypes, ranging from classic apoptosis to necrosis, has been described after TBI [27, 29]. However, retrospectively it seems that some cell death phenotypes previously described as necrotic might represent AIF-mediated apoptotic phenotypes, with peripheral chromatin condensation, less cellular and nuclear shrinkage (in comparison with caspase-dependent apoptosis), and large-scale DNA fragments.

Indeed, large-scale DNA fragments identified with pulsed-field DNA gel electrophoresis are much more readily detectable than classic DNA laddering after experimental TBI [56, 89].

Overall contribution of apoptosis after TBI

At present several unanswered questions remain. What is the relative proportion of neurons dying via apoptosis (as opposed to necrosis) after TBI, and is this proportion clinically meaningful? No study has directly measured the proportion of necrotic to apoptotic cell death in experimental TBI; however, information can be extrapolated from previous studies. For example, a 30% reduction in lesion volume is seen in rats treated with the caspase-3 inhibitor N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-fluoromethylketone (DEVD) measured 3 weeks after TBI compared with vehicle-treated controls [38]. In transgenic mice overexpressing Bcl-2, in which both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways, but less probably necrosis, would be inhibited, a 60% reduction in lesion volume is seen in comparison with wild-type mice [90]. Thus, although speculative, in experimental models of TBI roughly one-third of cell death might be attributable to caspase-dependent apoptosis, one-third to caspase-independent apoptosis, and one-third to necrosis. This degree of programmed cell death would seem to represent a sizeable therapeutic target, and might be underestimating the total amount of apoptosis occurring after TBI, given the clinical studies showing protracted cell death extending months after injury [86]; whether or not this represents apoptotic cell death remains to be strictly defined.

What cells undergo apoptosis after TBI? Although most research, including our own, has focused on neuronal apoptosis after TBI, other resident brain cells also undergo apoptosis. Astrocytes, important in glutamate uptake and in the production of lactate and antioxidants after injury [91, 92], demonstrate DNA fragmentation without classic apoptotic phenotypes after TBI, although to a much smaller degree than neurons [93, 94]. Oligodendrocytes also undergo apoptosis after TBI in rats and humans [84, 94]. Current opinion is that the order of vulnerability to apoptosis after TBI is neurons ≥ oligodendrocytes > astrocytes > microglia [95]. The reasons behind this differential vulnerability remain speculative, but might involve higher metabolic rates and therefore higher potential for relative ischemia in neurons.

It would also be interesting to determine whether there is a relationship between apoptosis and other prevalent clinical conditions seen after TBI. Temporal patterns of apoptosis [29] are similar to those seen for edema [96] and inflammation [97], with 'peak levels' seen between 24 and 72 hours after injury. Whereas in developmental apoptosis these conditions are felt to be mutually exclusive, ischemia resulting from edema-related increases in intracranial pressure could trigger apoptosis, as could inflammation. Hemorrhage generally precedes the occurrence of apoptosis after TBI, blood components are potent stimulators of apoptosis experimentally, and apoptosis is seen in humans with subarachnoid hemorrhage [98]. In addition, caspase inhibitors reduce endothelial apoptosis and prevent vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage in dogs [99].

Does classic developmental apoptosis occur after TBI in the mature mammalian brain? This topic is quite controversial, and partly depends on semantics [100]. Certainly there are caveats related to evaluating mechanisms of programmed cell death after brain injury. This is in part related to imprecise tools for identification. The most publicized example is that of TUNEL to identify DNA fragmentation, given that TUNEL will label both apoptotic and necrotic cells [101]. In models of cerebral ischemia, electron microscopic examination of injured brain has led some investigators to conclude that apoptosis does not contribute to cell death [102]. What is clear is the heterogeneous CNS diseases such as TBI and ischemia often result in a continuum of cell death phenotypes [103] that span from classic apoptosis to necrosis, and that many components of the programmed cell death cascade can be identified in multiple contemporary CNS injury models and in humans after TBI.

Should apoptosis be targeted after TBI? Inhibiting apoptosis after pathological insults remains controversial because apoptosis is an evolutionarily conserved and vital mechanism for biological systems to eliminate abnormal or aging cells. This is essentially the opposite biological predicament to that seen with the use of chemotherapeutic agents designed to kill cells. However, experimental studies still support a beneficial effect of treatment with strategies that inhibit apoptosis after acute brain insults such as TBI. Molecular approaches that interrupt the apoptosis cascade have been enlightening and have provided proof of principle [90]; however, at present these seem to be far from clinical application. Preclinical studies interrupting apoptosis using contemporary models of TBI have shown promise [38, 40, 104]. Although pharmacologic therapies targeting apoptosis after TBI might not quite be ready for the clinic, they are in rapid development and could be in clinical trials soon.

Potential therapeutic interventions targeting apoptosis after TBI

The complexity of the apoptotic cascade provides many opportunities, or perhaps more so challenges, for the design of interventions that might attenuate cell death (Fig. 1). Several hypothetical therapeutic approaches for reducing apoptosis after brain injury exist: first, inhibiting key initiators (for example with soluble inactive TNF-family receptors, anti-excitotoxic agents, or anti-oxidants); second, blocking key components of the apoptotic cascade (for example with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 mimetic proteins, caspase inhibitors, PARP inhibitors, other protease and/or endonuclease inhibitors); third, inhibiting multiple components of the apoptotic cascade (for example with hypothermia [105, 106]); and fourth, enhancing pro-survival factors (for example upregulating stress proteins or facilitating PKB signal transduction pathways). In our opinion, the two most promising strategies in terms of biological potential based on key positioning within the apoptotic cascade and on the availability of pharmacological agents are caspase inhibitors to target caspase-dependent apoptosis and PARP inhibitors to target caspase-independent cell death.

Caspase inhibitors

Caspase inhibitors include a group of small (typically one to four amino acids) peptide derivatives as well as novel non-peptide pharmacologic agents [107]. The peptide derivatives have been tested in models of brain injury and are competitive inhibitors designed according to specific amino acid target sequences at the cleavage site of the respective caspase substrates (reviewed in [68, 69]). A relatively selective tetrapeptide caspase-3 inhibitor has been shown in independent studies to inhibit caspase enzyme activity, reduce brain tissue loss, and improve neurological outcome after experimental TBI [38, 40]. Similarly a pan-caspase tri-peptide inhibitor has been shown to improve functional outcome after TBI in adult rats [36, 108] and to reduce apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain after TBI [36, 108]. A potential drawback of the tripeptide or tetrapeptide caspase inhibitors is that they might not penetrate the intact blood–brain barrier, unless delivered early after injury, when the blood–brain barrier is disrupted (typically hours after injury [109]). A unipeptide pan-caspase inhibitor Boc-aspartyl fluoromethylketone, which is capable of penetrating the blood–brain barrier, has been shown to reduce ischemic brain damage after systemic administration [110] but has not yet been reported in models of TBI. Important caveats aside from the potential for delayed tumor development exist in terms of treatment with caspase inhibitors. First, inhibition of caspase-dependent apoptosis might shift the mode of cell death to caspase-independent apoptosis or necrosis [111, 112]. Second, caspase activity might have an important homeostatic function in cytoskeletal remodeling and other physiologic processes [113]. Third, caspase inhibitors might lead to the survival of dysfunctional cells, resulting in survival without functional benefit. Consistent with this was our report that treatment with DEVD reduced tissue damage without improvement in functional outcome after TBI in rats [38].

PARP inhibitors

PARP is an important enzyme for the repair of DNA damage and maintenance of genomic integrity; however, increased PARP activity can exacerbate the depletion of cellular energy stores under certain conditions promoting cell death [114]. Although it is primarily felt to contribute to necrosis, a direct contribution of PARP activation to caspase-independent apoptosis mediated by AIF has recently been demonstrated [55, 63]. PARP inhibitors therefore represent one therapeutic strategy that might reduce caspase-independent apoptosis (and perhaps necrosis). Systemic administration of the PARP inhibitor 5-iodo-6-amino-1,2-benzopyrone at moderate dosing improved functional outcome after TBI in mice; however, higher doses that further inhibited PARP activity worsened performance in a memory paradigm [65]. Other PARP inhibitors have also been shown to afford protection in experimental models of TBI [115, 116]. None of these studies have directly assessed the affect of PARP inhibitors on apoptosis.

Other pharmacological strategies

Another potential strategy would be to block both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis by mitochondrial stabilization after TBI, either directly or through the regulation of the Bcl-2 family of proteins. Prevention of mitochondrial permeability transition with cyclosporine A or other immunophilins would attenuate the release of both cytochrome c and AIF [117]. Cyclosporine A and FK506 have been shown to be protective in models of TBI, at least in part by reducing mitochondrial dysfunction and traumatic axonal injury [118–122]. Recently, the novel p53 inhibitor pifithrin α was shown to improve histological and functional outcome in rats after cerebral ischemia [123].

Conclusion

Although apoptosis clearly contributes to secondary neuronal death after TBI both in experimental models and in humans, present studies have not been sufficient to confirm that apoptosis after brain injury is solely detrimental. Thus, there might be physiologic, as well as technical, limitations in approaches designed to reduce neuronal and glial apoptosis after TBI. The quiet elimination of cell debris and nonfunctional cells might be equally important for structural and functional recovery after TBI, being essentially 'molecular débridement'. That said, intuitively one would suspect that salvaging neurons after acute injury would optimize chances for maximal neurological recovery. Thus, it remains logical to continue the development of clinically relevant strategies targeting the selective reduction of apoptosis after TBI.

Abbreviations

- AIF:

-

= apoptosis-inducing factor

- Apaf-1:

-

= apoptotic protease activating factor-1

- Bad:

-

= Bcl-2 antagonist of cell death

- Bax:

-

= Bcl-2 associated X protein

- Bcl:

-

= B-cell lymphoma

- BH:

-

= Bcl-2 homology

- Bid:

-

= BH3 interacting death domain agonist

- CNS:

-

= central nervous system

- CSF:

-

= cerebrospinal fluid

- DEVD:

-

= N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-fluoromethylketone

- ER:

-

= endoplasmic reticulum

- MAPK:

-

= mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Mcl-1L:

-

= myeloid cell leukemia-1 long

- PARP:

-

= poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PKB:

-

= protein kinase B

- TBI:

-

= traumatic brain injury

- TNF:

-

= tumor necrosis factor

- TUNEL:

-

= terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling.

References

Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, Pepe PE: Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in U.S. emergency departments, 1992–1994. Acad Emerg Med 2000, 7: 134-140.

Adekoya N, Thurman DJ, White DD, Webb KW: Surveillance for traumatic brain injury deaths – United States, 1989–1998. Morb Mort Weekly Rept. Surveill Summ 2002, 51: 1-14.

Firsching R, Woischneck D: Present status of neurosurgical trauma in Germany. World J Surg 2001, 25: 1221-1223. 10.1007/s00268-001-0085-5

Engberg A, Teasdale TW: Traumatic brain injury in children in Denmark: a national 15-year study. Eur J Epidemiol 1998, 14: 165-173. 10.1023/A:1007492025190

Masson F, Thicoipe M, Aye P, et al.: Epidemiology of severe brain injuries: a prospective population-based study. J Trauma-Inj Infect Crit Care 2001, 51: 481-489. 10.1097/00005373-200109000-00010

Song SH, Kim SH, Kim KT, Kim Y: Outcome of pediatric patients with severe brain injury in Korea: a comparison with reports in the west. Childs Nervous System 1997, 13: 82-86. 10.1007/s003810050048

Gururaj G: Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries: Indian scenario. Neurol Res 2002, 24: 24-28. 10.1179/016164102101199503

Hawley CA, Ward AB, Magnay AR, Long J: Parental stress and burden following traumatic brain injury amongst children and adolescents. Brain Inj 2003, 17: 1-23. 10.1080/0269905021000010096

McGarry LJ, Thompson D, Millham FH, Cowell L, Snyder PJ, Lenderking WR, Weinstein MC: Outcomes and costs of acute treatment of traumatic brain injury. J Trauma-Inj Infect Crit Care 2002, 53: 1152-1159. 10.1097/00005373-200212000-00020

Sosin DM, Sniezek JE, Waxweiler RJ: Trends in death associated with traumatic brain injury, 1979 through 1992. Success and failure. JAMA 1995, 273: 1778-1780. 10.1001/jama.273.22.1778

Narayan RK, Michel ME, Ansell B, et al.: Clinical trials in head injury. J Neurotrauma 2002, 19: 503-557. 10.1089/089771502753754037

Ikonomidou C, Turski L: Why did NMDA receptor antagonists fail clinical trials for stroke and traumatic brain injury? Lancet Neurol 2002, 1: 383-386. 10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00164-3

Clifton GL, Miller ER, Choi SC, et al.: Lack of effect of induction of hypothermia after acute brain injury. N Engl J Med 2001, 344: 556-563. 10.1056/NEJM200102223440803

Lenzlinger PM, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Laurer HL, McIntosh TK: The duality of the inflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol 2001, 24: 169-181. 10.1385/MN:24:1-3:169

Liou AK, Clark RS, Henshall DC, Yin XM, Chen J: To die or not to die for neurons in ischemia, traumatic brain injury and epilepsy: a review on the stress-activated signaling pathways and apoptotic pathways. Prog Neurobiol 2003, 69: 103-142. 10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00005-4

Lockshin RA: Programmed cell death. Activation of lysis by a mechanism involving the synthesis of protein. J Insect Physiol 1969, 15: 1505-1516. 10.1016/0022-1910(69)90172-3

Marovitz WF, Shugar JM, Khan KM: The role of cellular degeneration in the normal development of (rat) otocyst. Laryngoscope 1976, 86: 1413-1425.

Webster DA, Gross J: Studies on possible mechanisms of programmed cell death in the chick embryo. Dev Biol 1970, 22: 157-184.

Kerr JF: A histochemical study of hypertrophy and ischaemic injury of rat liver with special reference to changes in lysosomes. J Pathol Bacteriol 1965, 90: 419-435.

Kerr JF: Shrinkage necrosis: a distinct mode of cellular death. J Pathol 1971, 105: 13-20.

Kerr JF, Searle J: The digestion of cellular fragments within phagolysosomes in carcinoma cells. J Pathol 1972, 108: 55-58.

Wyllie AH, Kerr JF, Currie AR: Cell death in the normal neonatal rat adrenal cortex. J Pathol 1973, 111: 255-261.

Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR: Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer 1972, 26: 239-257.

Duvall E, Wyllie AH, Morris RG: Macrophage recognition of cells undergoing programmed cell death (apoptosis). Immunol 1985, 56: 351-358.

Martin JB: Huntington's disease: genetically programmed cell death in the human central nervous system. Nature 1982, 299: 205-206. 10.1038/299205a0

Schutta HS, Kassell NF, Langfitt TW: Brain swelling produced by injury and aggravated by arterial hypertension. A light and electron microscopic study. Brain 1968, 91: 281-294.

Rink A, Fung K-M, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM-Y, Neugebauer E, McIntosh TK: Evidence of apoptotic cell death after experimental traumatic brain injury in the rat. Am J Pathol 1995, 147: 1575-1583.

Colicos MA, Dash PK: Apoptotic morphology of dentate gyrus granule cells following experimental cortical impact injury in rats: possible role in spatial memory deficits. Brain Res 1996, 739: 120-131. 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)00824-4

Clark RSB, Kochanek PM, Dixon CE, Chen M, Marion DW, Heineman S, DeKosky ST, Graham SH: Early neuropathologic effects of mild or moderate hypoxemia after controlled cortical impact injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 1997, 14: 179-189.

Evans JP, Scheinker IM: Histologic studies of the brain following head trauma: late changes, atrophic sclerosis of the white matter. J Neurosurg 1944, 1: 306-320.

Evans JP, Scheinker IM: Histologic studies of the brain following head trauma: post-traumatic cerebral swelling and edema. J Neurosurg 1945, 2: 306-314.

Clark RS, Kochanek PM, Chen M, Watkins SC, Marion DW, Chen J, Hamilton RL, Loeffert JE, Graham SH: Increases in Bcl-2 and cleavage of Caspase-1 and Caspase-3 in human brain after head injury. FASEB J 1999, 13: 813-821.

Clark RSB, Chen M, Kochanek PM, et al.: Detection of single-and double-strand DNA breaks after traumatic brain injury in rats: comparison of in situ labeling techniques using DNA polymerase I, the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. J Neurotrauma 2001, 18: 675-689. 10.1089/089771501750357627

Borisenko GG, Matsura T, Liu SX, Tyurin VA, Jianfei J, Serinkan FB, Kagan VE: Macrophage recognition of externalized phosphatidylserine and phagocytosis of apoptotic Jurkat cells–existence of a threshold. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003, 413: 41-52. 10.1016/S0003-9861(03)00083-3

Zhang X, Satchell MA, Clark RSB, Nathaniel PD, Kochanek PM, Graham SH: Apoptosis. In In Brain Injury. Edited by: Clark RSB, Kochanek PM. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001:199-230.

Knoblach SM, Nikolaeva M, Huang X, Fan L, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Faden AI: Multiple caspases are activated after traumatic brain injury: evidence for involvement in functional outcome. J Neurotrauma 2002, 19: 1155-1170. 10.1089/08977150260337967

Salvesen GS, Dixit VM: Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell 1997, 91: 443-446. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80430-4

Clark RSB, Kochanek PM, Watkins SC, et al.: Caspase-3 mediated neuronal death after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurochem 2000, 74: 740-753. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740740.x

Pike BR, Zhao X, Newcomb JK, Posmantur RM, Wang KK, Hayes RL: Regional calpain and caspase-3 proteolysis of alpha-spectrin after traumatic brain injury. Neuroreport 1998, 9: 2437-2442.

Yakovlev AG, Knoblach SM, Fan L, Fox GB, Goodnight R, Faden AI: Activation of CPP32-like caspases contributes to neuronal apoptosis and neurological dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci 1997, 17: 7415-7424.

Cheema ZF, Wade SB, Sata M, Walsh K, Sohrabji F, Miranda RC: Fas/Apo [apoptosis]-1 and associated proteins in the differentiating cerebral cortex: induction of caspase-dependent cell death and activation of NF-κB. J Neurosci 1999, 19: 1754-1770.

Qiu J, Whalen MJ, Lowenstein P, Fiskum G, Fahy B, Darwish R, Aarabi B, Yuan J, Moskowitz MA: Upregulation of the Fas receptor death-inducing signaling complex after traumatic brain injury in mice and humans. J Neurosci 2002, 22: 3504-3511.

Kischkel FC, Lawrence DA, Tinel A, et al.: Death receptor recruitment of endogenous caspase-10 and apoptosis initiation in the absence of caspase-8. J Biol Chem 2001, 276: 46639-46646. 10.1074/jbc.M105102200

Zou H, Henzel WJ, Liu X, Lutschg A, Wang X: Apaf-1, a human protein homologous to C. elegans CED-4, participates in cytochrome c-dependent activation of caspase-3. Cell 1997, 90: 405-413. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80501-2

Boehning D, Patterson RL, Sedaghat L, Glebova NO, Kurosaki T, Snyder SH: Cytochrome c binds to inositol (1,4,5) triphosphate receptors amplifying calcium-dependent apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 2003, 5: 1051-1061. 10.1038/ncb1063

Hetz C, Russelakis-Carneiro M, Maundrell K, Castilla J, Soto C: Caspase-12 and endoplasmic reticulum stress mediate neurotoxicity of pathological prion protein. EMBO J 2003, 22: 5435-5445. 10.1093/emboj/cdg537

Larner SF, Hayes RL, McKinsey DM, Pike BR, Wang KKW: Increased expression and processing of caspase-12 after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurochem 2004, 88: 78-90.

Fischer H, Koenig U, Eckhart L, Tschachler E: Human caspase 12 has acquired deleterious mutations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002, 293: 722-726. 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00289-9

Saleh M, Vaillancourt JP, Graham RK, et al.: Differential modulation of endotoxin responsiveness by human caspase-12 polymorphisms. Nature 2004, 429: 75-79. 10.1038/nature02451

Buki A, Okonkwo DO, Wang KK, Povlishock JT: Cytochrome c release and caspase activation in traumatic axonal injury. J Neurosci 2000, 20: 2825-2834.

Saatman KE, Murai H, Bartus RT, Smith DH, Hayward NJ, Perri BR, McIntosh TK: Calpain inhibitor AK295 attenuates motor and cognitive deficits following experimental brain injury in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93: 3428-3433. 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3428

Kampfl A, Whitson JS, Zhao X, Posmantur R, Clifton G, Hayes RL: Calpain inhibitors reduce depolarization induced loss of neuroflament proteins in primary septo-hippocampal cultures. Neurosci Lett 1995, 194: 149-152. 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11745-I

Seyfried D, Han Y, Zheng Z, Day N, Moin K, Rempel S, Sloane B, Chopp M: Cathepsin B and middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Neurosurg 1997, 87: 716-723.

Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, et al.: Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature 1999, 397: 441-446. 10.1038/17135

Du L, Zhang X, Han YY, et al.: Intra-mitochondrial poly-ADP-ribosylation contributes to NAD+depletion and cell death induced by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 2003, 278: 18426-18433. 10.1074/jbc.M301295200

Zhang X, Chen J, Graham SH, et al.: Intranuclear localization of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and large scale DNA fragmentation after traumatic brain injury in rats and in neuronal cultures exposed to peroxynitrite. J Neurochem 2002, 82: 181-191. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00975.x

Cao G, Clark RS, Pei W, Yin W, Zhang F, Sun FY, Graham SH, Chen J: Translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor in vulnerable neurons after transient cerebral ischemia and in neuronal cultures after oxygen-glucose deprivation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2003, 23: 1137-1150. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000087090.01171.E7

Li LY, Luo X, Wang X: Endonuclease G is an apoptotic DNase when released from mitochondria. Nature 2001, 412: 95-99. 10.1038/35083620

Suzuki Y, Imai Y, Nakayama H, Takahashi K, Takio K, Takahashi R: A serine protease, HtrA2, is released from the mitochondria and interacts with XIAP, inducing cell death. Mol Cell 2001, 8: 613-621. 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00341-0

Chai J, Du C, Wu JW, Kyin S, Wang X, Shi Y: Structural and biochemical basis of apoptotic activation by Smac/DIABLO. Nature 2000, 406: 855-862. 10.1038/35022514

Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Brustugun OT, Doskeland SO: Injected cytochrome c induces apoptosis. Nature 1998, 391: 449-450. 10.1038/35060

Klein JA, Longo-Guess CM, Rossmann MP, Seburn KL, Hurd RE, Frankel WN, Bronson RT, Ackerman SL: The harlequin mouse mutation downregulates apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature 2002, 419: 367-374. 10.1038/nature01034

Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, Coombs C, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, Dawson VL: Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science 2002, 297: 259-263. 10.1126/science.1072221

Szabo C: DNA strand breakage and activation of poly-ADP ribosyltransferase: a cytotoxic pathway triggered by peroxynitrite. Free Radic Biol Med 1996, 21: 855-869. 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00170-0

Satchell MA, Zhang X, Kochanek PM, Dixon CE, Jenkins LW, Melick JA, Szabo C, Clark RS: A dual role for poly-ADP-ribosylation in spatial memory acquisition after traumatic brain injury in mice involving NAD+depletion and ribosylation of 14-3-3gamma. J Neurochem 2003, 85: 697-708.

Graham SH, Chen J, Clark RS: Bcl-2 family gene products in cerebral ischemia and traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2000, 17: 831-841.

Harris MH, Thompson CB: The role of the Bcl-2 family in the regulation of outer mitochondrial membrane permeability. Cell Death Differ 2000, 7: 1182-1191. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400781

Bilsland J, Harper S: Caspases and neuroprotection. Curr Opin Invest Drugs 2002, 3: 1745-1752.

Concha NO, Abdel-Meguid SS: Controlling apoptosis by inhibition of caspases. Curr Medicinal Chem 2002, 9: 713-726.

Rosse T, Olivier R, Monney L, Rager M, Conus S, Fellay I, Jansen B, Borner C: Bcl-2 prolongs cell survival after Bax-induced release of cytochrome c . Nature 1998, 391: 496-499. 10.1038/35160

Antonsson B, Conti F, Ciavatta AM, et al.: Inhibition of Bax channel-forming activity by Bcl-2. Science 1997, 277: 370-372. 10.1126/science.277.5324.370

Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J: Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell 1998, 94: 491-501. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81590-1

Clark RSB, Chen J, Watkins SC, Kochanek PM, Chen M, Stetler RA, Loeffert JE, Graham SH: Apoptosis-suppressor gene bcl-2 expression after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurosci 1997, 17: 9172-9182.

Seidberg N, Clark RS, Zhang X, Lai Y, Chen M, Graham SH, Kochanek PM, Watkins SC, Marion DW: Alterations in inducible 72 kilodalton heat shock protein and the chaperone cofactor BAG-1 in human brain after head injury. J Neurochem 2003, 84: 514-521. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01547.x

Mori T, Wang X, Jung JC, Sumii T, Singhal AB, Fini ME, Dixon CE, Alessandrini A, Lo EH: Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition in traumatic brain injury: in vitro and in vivo effects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2002, 22: 444-452. 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00008

Otani N, Nawashiro H, Fukui S, Nomura N, Yano A, Miyazawa T, Shima K: Differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways after traumatic brain injury in the rat hippocampus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2002, 22: 327-334. 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00010

Yang K, Taft WC, Dixon CE, Todaro CA, Yu RK, Hayes RL: Alterations of protein kinase C in rat hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 1993, 10: 287-295.

Jenkins LW, Dixon CE, Peters G, Gao WM, Zhang X, Adelson PD, Kochanek PM: Cell signaling: serine/threonine protein kinases and traumatic brain injury. In In Brain Injury. Edited by: Clark RS, Kochanek PM. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001:163-180.

Noshita N, Lewen A, Sugawara T, Chan PH: Akt phosphorylation and neuronal survival after traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurobiol Dis 2002, 9: 294-304. 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0482

Ang BT, Yap E, Lim J, Tan WL, Ng PY, Ng I, Yeo TT: Poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase expression in human traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 2003, 99: 125-130.

Zhang X, Graham SH, Kochanek PM, Marion DW, Nathaniel PD, Watkins SC, Clark RS: Caspase-8 expression and proteolysis in human brain after severe head injury. FASEB J 2003, 17: 1367-1369.

Ertel W, Keel M, Stocker R, Imhof HG, Leist M, Steckholzer U, Tanaka M, Trentz O, Nagata S: Detectable concentrations of Fas ligand in cerebrospinal fluid after severe head injury. J Neuroimmunol 1997, 80: 93-96. 10.1016/S0165-5728(97)00139-2

Lenzlinger PM, Marx A, Trentz O, Kossmann T, Morganti-Kossmann MC: Prolonged intrathecal release of soluble Fas following severe traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neuroimmunol 2002, 122: 167-174. 10.1016/S0165-5728(01)00466-0

Clark RS, Kochanek PM, Adelson PD, et al.: Increases in bcl-2 protein in cerebrospinal fluid and evidence for programmed cell death in infants and children after severe traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr 2000, 137: 197-204. 10.1067/mpd.2000.107616

Ng I, Yeo TT, Tang WY, Soong R, Ng PY, Smith DR: Apoptosis occurs after cerebral contusions in humans. Neurosurgery 2000, 46: 949-956. 10.1097/00006123-200004000-00034

Williams S, Raghupathi R, MacKinnon MA, McIntosh TK, Saatman KE, Graham DI: In situ DNA fragmentation occurs in white matter up to 12 months after head injury in man. Acta Neuropathol 2001, 102: 581-590.

Smith FM, Raghupathi R, MacKinnon MA, McIntosh TK, Saatman KE, Meaney DF, Graham DI: TUNEL-positive staining of surface contusions after fatal head injury in man. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000, 100: 537-545. 10.1007/s004010000222

Jenkins LW, Moszynski K, Lyeth BG, et al.: Increased vulnerability of the mildly traumatized rat brain to cerebral ischemia: the use of controlled secondary ischemia as a research tool to identify common or different mechanisms contributing to mechanical and ischemic brain injury. Brain Res 1989, 477: 211-224. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91409-1

Eldadah BA, Yakovlev AG, Faden AI: A new approach for the electrophoretic detection of apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res 1996, 24: 4092-4093. 10.1093/nar/24.20.4092

Raghupathi R, Fernandez SC, Murai H, Trusko SP, Scott RW, Nishioka WK, McIntosh TK: BCL-2 overexpression attenuates cortical cell loss after traumatic brain injury in transgenic mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998, 18: 1259-1269. 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00013

Wang XF, Cynader MS: Astrocytes provide cysteine to neurons by releasing glutathione. J Neurochemistry 2000, 74: 1434-1442. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741434.x

Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ: Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: A mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91: 10625-10629.

Newcomb JK, Zhao X, Pike BR, Hayes RL: Temporal profile of apoptotic-like changes in neurons and astrocytes following controlled cortical impact injury in the rat. Exp Neurol 1999, 158: 76-88. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7071

Beer R, Franz G, Krajewski S, et al.: Temporal and spatial profile of caspase 8 expression and proteolysis after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem 2001, 78: 862-873. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00460.x

Conti AC, Raghupathi R, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK: Experimental brain injury induces regionally distinct apoptosis during the acute and delayed post-traumatic period. J Neurosci 1998, 18: 5663-5672.

Uhl MW, Biagas KV, Grundl PD, Barmada MA, Schiding JK, Nemoto EM, Kochanek PM: Effects of neutropenia on edema, histology, and cerebral blood flow after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 1994, 11: 303-315.

Clark RSB, Schiding JK, Kaczorowski SL, Marion DW, Kochanek PM: Neutrophil accumulation after traumatic brain injury in rats: comparison of weight-drop and controlled cortical impact models. J Neurotrauma 1994, 11: 499-506.

Nau R, Haase S, Bunkowski S, Bruck W: Neuronal apoptosis in the dentate gyrus in humans with subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral hypoxia. Brain Pathol 2002, 12: 329-336.

Zhou C, Yamaguchi M, Kusaka G, Schonholz C, Nanda A, Zhang JH: Caspase inhibitors prevent endothelial apoptosis and cerebral vasospasm in dog model of experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2004, 24: 419-431. 10.1097/00004647-200404000-00007

Sloviter RS: Apoptosis: a guide for the perplexed. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2002, 23: 19-24. 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01867-8

Charriaut-Marlangue C, Ben-Ari Y: A cautionary note on the use of the TUNEL stain to determine apoptosis. Neuroreport 1995, 7: 61-64.

Deshpande J, Bergstedt K, Linden T, Kalimo H, Wieloch T: Ultra-structural changes in the hippocampal CA1 region following transient cerebral ischemia: evidence against programmed cell death. Exp Brain Res 1992, 88: 91-105.

Portera-Cailliau C, Price DL, Martin LJ: Non-NMDA and NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxic neuronal deaths in adult brain are morphologically distinct: further evidence for an apoptosis–necrosis continuum. J Comp Neurol 1997, 378: 88-104. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19970203)378:1<88::AID-CNE5>3.3.CO;2-C

Morita-Fujimura Y, Fujimura M, Kawase M, Murakami K, Kim GW, Chan PH: Inhibition of interleukin-1β converting enzyme family proteases (caspases) reduces cold injury-induced brain trauma and DNA fragmentation in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1999, 19: 634-642. 10.1097/00004647-199906000-00006

Edwards AD, Yue X, Squier MV, et al.: Specific inhibition of apoptosis after cerebral hypoxia–ischaemia by moderate post-insult hypothermia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995, 217: 1193-1199. 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2895

Xu RX, Nakamura T, Nagao S, Miyamoto O, Jin L, Toyoshima T, Itano T: Specific inhibition of apoptosis after cold-induced brain injury by moderate postinjury hypothermia. Neuro-surgery 1998, 43: 107-114.

Lee D, Long SA, Adams JL, et al.: Potent and selective nonpeptide inhibitors of caspases 3 and 7 inhibit apoptosis and maintain cell functionality. J Biol Chem 2000, 275: 16007-16014. 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16007

Felderhoff-Mueser U, Sifringer M, Pesditschek S, Kuckuck H, Moysich A, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C: Pathways leading to apoptotic neurodegeneration following trauma to the developing rat brain. Neurobiol Dis 2002, 11: 231-245. 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0521

Adelson PD, Whalen MJ, Kochanek PM, Robichaud P, Carlos TM: Blood brain barrier permeability and acute inflammation in two models of traumatic brain injury in the immature rat: a preliminary report. Acta Neurochir Suppl 1998, 71: 104-106.

Cheng Y, Deshmukh M, D'Costa A, et al.: Caspase inhibitor affords neuroprotection with delayed administration in a rat model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Clin Invest 1998, 101: 1992-1999.

Los M, Mozoluk M, Ferrari D, Stepczynska A, Stroh C, Renz A, Herceg Z, Wang ZQ, Schulze-Osthoff K: Activation and caspase-mediated inhibition of PARP: a molecular switch between fibroblast necrosis and apoptosis in death receptor signaling. Mol Biol Cell 2002, 13: 978-988. 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0272

Lemaire C, Andreau K, Souvannavong V, Adam A: Inhibition of caspase activity induces a switch from apoptosis to necrosis. FEBS Lett 1998, 425: 266-270. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00252-X

Dash PK, Blum S, Moore AN: Caspase activity plays an essential role in long-term memory. Neuroreport 2000, 11: 2811-2816.

Szabo C, Dawson VL: Role of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase in inflammation and ischaemia-reperfusion. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1998, 19: 287-298. 10.1016/S0165-6147(98)01193-6

Lacza Z, Horvath EM, Komjati K, Hortobagyi T, Szabo C, Busija DW: PARP inhibition improves the effectiveness of neural stem cell transplantation in experimental brain trauma. Int J Mol Med 2003, 12: 153-159.

LaPlaca MC, Zhang J, Raghupathi R, Li JH, Smith F, Bareyre FM, Snyder SH, Graham DI, McIntosh TK: Pharmacologic inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is neuroprotective following traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 2001, 18: 369-376. 10.1089/089771501750170912

Snyder SH, Lai MM, Burnett PE: Immunophilins in the nervous system. Neuron 1998, 21: 283-294. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80538-3

Sullivan PG, Thompson MB, Scheff SW: Cyclosporin A attenuates acute mitochondrial dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 1999, 160: 226-234. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7197

Okonkwo DO, Povlishock JT: An intrathecal bolus of cyclosporin A before injury preserves mitochondrial integrity and attenuates axonal disruption in traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1999, 19: 443-451. 10.1097/00004647-199904000-00010

Okonkwo DO, Buki A, Siman R, Povlishock JT: Cyclosporin A limits calcium-induced axonal damage following traumatic brain injury. Neuroreport 1999, 10: 353-358.

Scheff SW, Sullivan PG: Cyclosporin A significantly ameliorates cortical damage following experimental traumatic brain injury in rodents. J Neurotrauma 1999, 16: 783-792.

Singleton RH, Stone JR, Okonkwo DO, Pellicane AJ, Povlishock JT: The immunophilin ligand FK506 attenuates axonal injury in an impact-acceleration model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2001, 18: 607-614. 10.1089/089771501750291846

Leker RR, Ahronowiz M, Greig NH, Ovadia H: The role of p53-induced apoptosis in cerebral ischemia: effects of the p53 inhibitor pifithrin alpha. Exp Neurol 2004, 187: 487-486. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.030

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate generous support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurologic Diseases and Stroke (RO1 NS38620 and P50 NS30318); the Department of Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; and the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Chen, Y., Jenkins, L.W. et al. Bench-to-bedside review: Apoptosis/programmed cell death triggered by traumatic brain injury. Crit Care 9, 66 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2950

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2950