Abstract

In patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the lung comprises areas of aeration and areas of alveolar collapse, the latter producing intrapulmonary shunt and hypoxemia. The currently suggested strategy of ventilation with low lung volumes can aggravate lung collapse and potentially produce lung injury through shear stress at the interface between aerated and collapsed lung, and as a result of repetitive opening and closing of alveoli. An 'open lung strategy' focused on alveolar patency has therefore been recommended. While positive end-expiratory pressure prevents alveolar collapse, recruitment maneuvers can be used to achieve alveolar recruitment. Various recruitment maneuvers exist, including sustained inflation to high pressures, intermittent sighs, and stepwise increases in positive end-expiratory pressure or peak inspiratory pressure. In animal studies, recruitment maneuvers clearly reverse the derecruitment associated with low tidal volume ventilation, improve gas exchange, and reduce lung injury. Data regarding the use of recruitment maneuvers in patients with ARDS show mixed results, with increased efficacy in those with short duration of ARDS, good compliance of the chest wall, and in extrapulmonary ARDS. In this review we discuss the pathophysiologic basis for the use of recruitment maneuvers and recent evidence, as well as the practical application of the technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ventilatory management protocols for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are continually evolving and improving. Strategies have changed from optimizing convenient physiologic variables, such as oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, to protecting the lung from injury. Nevertheless, much remains unknown and some controversy persists [1, 2]. One of the more recent areas of research and clinical interest involves lung volume recruitment. This refers to the dynamic process of opening previously collapsed lung units by increasing transpulmonary pressure. The concept of opening the injured lung is not new [3, 4], but recent experimental data suggest that this intervention may play an important role in preventing ventilator-induced lung injury [5], although this has not been uniformly supported by clinical studies. This review describes the pathophysiologic basis and clinical role for lung recruitment maneuvers. Several recent publications have reviewed this topic in some detail [6, 7]; the present review aims to describe these concepts in a format that may be useful to the practicing intensivist, bringing laboratory and clinical research to bedside practice.

Why recruit the lung?

What we know

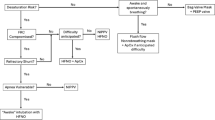

The acutely injured lung comprises a heterogeneous environment of aerated and nonaerated lung (Fig. 1) [8], the nonaerated lung consisting of collapsed or consolidated alveoli. Positive pressure ventilation generates tensions at the boundaries between aerated and nonaerated lung, and repeated high-pressure inflations may cause damaging shearing forces at these junctional interfaces [9]. Another stress induced by positive pressure ventilation is the cyclic opening and closing of alveoli, in the presence of inadequate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) to maintain alveolar patency through the respiratory cycle [10]. These mechanical stresses may have a number of effects, including epithelial and endothelial damage, cellular inflammatory damage, and release of cytokines [5, 11].

Schematic representation of mechanisms of injury during tidal ventilation. Dependent areas are poorly aerated at end-expiration because of compressing hydrostatic pressures. At end-inspiration, patent alveoli may become over-stretched (A), excessive stresses may be generated at the boundary between aerated and nonaerated lung tissue (B), and dependent alveoli may be repetitively opened and closed producing tissue damage (C).

Pressure-limited ventilatory strategies have been introduced to limit these ventilator-induced stresses [12, 13], but they do not address the primary problem of inhomogeneity of the aeration of the lung. In fact, reduced tidal volumes are probably responsible for increasing alveolar derecruitment [14]. From a pathophysiologic perspective, attempts to open the nonaerated lung units seem appropriate, bearing in mind that only collapsed but not consolidated alveoli are likely to respond [15]. Recruitment appears to be a continuous process that occurs throughout the pressure–volume curve and not all lung units are recruitable at safe pressures [16]. In general, lung units can be kept open by airway pressures that are lower than those required to open them [16], leading to the concept of recruitment using periodic higher pressure maneuvers with moderate levels of PEEP to maintain alveolar patency. The 'open' lung is ventilated on the expiratory limb of the pressure–volume curve, rather than the underinflated lung on the inspiratory portion of the curve (Fig. 2).

Pressure–volume curve demonstrating tidal ventilation at various positive end-expiratory pressure levels. Tidal ventilation is shown at 12, 18 and 24 cmH2O with no recruitment effect (solid lines); at 18 cmH2O with partial recruitment (18a), and at 12 and 24 cmH2O following an effective recruitment manuever (12a, 24a).

In animal models of acute lung injury lung recruitment maneuvers have been demonstrated to improve oxygenation and to open nonaerated lung [4, 17]. Recruitment maneuvers may have differential effects depending on the mechanism of lung injury [18]. Because of the increased atelectasis, they appear to be more effective in situations in which a low PEEP is being used, and the benefit is far less in a high PEEP model [4, 18]. It was recently demonstrated that recruitment strategies may prevent microvascular leak and right ventricular dysfunction in rats without pre-existing lung injury undergoing pressure limited ventilation [19].

The findings of clinical studies of recruitment maneuvers in patients with ARDS have been variable. This may relate to heterogeneity of the patients studied in terms of their underlying lung disease, duration of ARDS, and method of recruitment [20, 21]. Several studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect on oxygenation, which is sustained in the presence of adequate PEEP [22–24]. Patients ventilated in the supine position benefit more than when in the prone position, which is probably related to the presence of more dependent, collapsed lung [21, 25]. Similarly, the oxygenation benefit of recruitment maneuvers in patients ventilated with a high PEEP strategy is only modest [21]. Several other clinical studies have demonstrated minimal or no beneficial effect of recruitment maneuvers [26, 27]. A study of a moderate sustained inflation (35 cmH2O for 30 s) in patients on a relatively high PEEP ventilation protocol demonstrated only a small and variable improvement in oxygenation, which was not sustained [26].

Another potential role for lung recruitment maneuvers is in the evaluation of the appropriate PEEP and tidal volume combination for a patient, and to gauge responsiveness to PEEP [20]. A decremental PEEP trial following a recruitment maneuver can identify the PEEP level required to prevent derecruitment [28].

What we still need to know

Recruitment maneuvers clearly improve oxygenation in some patients with ARDS. However, it remains unknown whether this is associated with a reduction in ventilator-induced lung injury, as has been demonstrated in animal models. Few randomized controlled trials incorporating lung volume recruitment maneuvers have been published. The study conducted by Amato and coworkers [29] demonstrated a mortality benefit in the arm treated with pressure limitation and an open lung approach that included recruitment maneuvers. It is difficult to determine the beneficial effect of the recruitment component given the other significant differences in ventilatory strategy. A US National Institutes of Health funded study comparing pressure limited ventilation using a high PEEP strategy (including recruitment maneuvers) with a low PEEP strategy was discontinued early because of a lack of benefit [30]. A large Canadian study incorporating recruitment maneuvers into a lung protective strategy is nearing completion.

How to recruit the lung

What we know

Many recent innovations in mechanical ventilation provide their benefit largely through recruitment of derecruited lung units, including high frequency oscillation, partial liquid ventilation, and prone positioning [31]. In this section of the review, lung volume recruitment maneuvers are described that can be applied to the patient on conventional modalities of ventilation.

Animal and clinical studies have described diverse methods for recruiting the lung. A sustained high-pressure inflation uses pressures from 35 to 50 cmH2O for a duration of 20–40 s [22, 27, 29]. Pressure may need to be individualized, with higher airway pressures required to generate an equivalent transpulmonary pressure in the patient with increased intra-abdominal pressure. Bladder pressure measurements can be used to identify these patients. A sustained inflation is usually achieved by changing to a CPAP mode and setting the pressure to the desired level. It is important to ensure that the pressure support level is set to zero to avoid additional pressure increases. Paralysis is usually not required for sustained inflations, but additional short-acting sedation may be useful. The patient should be closely monitored during this short period for hypotension and hypoxemia. Intermittent sighs have been demonstrated to achieve recruitment, using three consecutive sighs set at 45 cmH2O pressure [23]. An 'extended sigh' has been described, involving a stepwise increase in PEEP and decrease in tidal volume over 2 min to a CPAP level of 30 cmH2O for 30 s [32]. Other methods include an intermittent increase in PEEP for two breaths every minute [24] and increasing peak inspiratory pressure by increments of 10 cmH2O to levels greater than 60 cmH2O for brief periods [33]. Increasing the ventilatory pressures to a peak pressure of 50 cmH2O for 30–120 s may provide equivalent recruitment effects [34–36]. The effect of recruitment may not be sustained unless adequate PEEP is applied to prevent derecruitment [21, 22, 28].

The effect of recruitment maneuvers can be monitored at the bedside using gas exchange indices or physiological parameters such as lung compliance. Imaging techniques, including chest radiography or computed tomography, may also be useful. Bedside evaluation of recruitment was discussed in detail in a recent review [37]. From a practical perspective, improved oxygenation with a reduction in partial carbon dioxide tension indicates lung recruitment. Pressure effects may redirect blood flow and improve oxygenation in the absence of recruitment, but this would not be associated with a reduced partial carbon dioxide tension.

What we still need to know

Despite the increasing body of literature on recruitment, few studies have compared the various methods in terms of efficacy and adverse effects. Sustained high pressure may cause transient hypotension, and may be less well tolerated than methods using higher pressure ventilation. Sustained or intermittent increases in peak pressure carry a risk for barotrauma. The choice of recruitment maneuver may depend on the baseline ventilatory mode; a spontaneously breathing patient may not tolerate a sustained high-pressure inflation, and a transient increase in PEEP and peak pressure may be more appropriate in this situation. There is some evidence that the type of lung injury (pulmonary versus extrapulmonary) may affect tolerance to and efficacy of various recruitment modalities [21]. The frequency with which recruitment maneuvers must be applied is also unknown. This probably depends on the underlying disease, the level of PEEP, and procedures such as endotracheal suctioning [35]. Other than the study conducted by Amato and coworkers [29], no outcome data exist suggesting that there is a mortality benefit from recruitment maneuvers.

Who needs recruitment and when?

What we know

Although most studies have evaluated recruitment maneuvers within the context of ARDS, this intervention may be of value in patients with atelectasis related to general anesthesia [38], during postoperative ventilation [39], following suctioning [35], or in other conditions that produce hypoxemia including heart failure. Response to recruiting interventions does not occur in all patients with ARDS [40, 41], and several studies have identified characteristics that may predict a response, in terms of oxygenation or improved lung mechanics.

The duration of ARDS appears to be an important factor, with a higher response rate noted in patients early in their disease course (e.g. < 72 hours) than later [41]. This probably relates to the change in disease from an exudative to a fibroproliferative process. Similarly, the underlying pulmonary process may have an impact on responsiveness to recruitment attempts. Patients with extrapulmonary ARDS (e.g. secondary to sepsis) have a higher response rate than those with pulmonary ARDS (e.g. pneumonia) [15, 23]. Patients with pneumonia may have a limited amount of recruitable lung tissue, and the higher pressure may overinflate normal lung rather than aerating the consolidated tissue [16]. The effect of recruitment maneuvers may be limited by the ability of the chest wall to expand. Patients with poor chest wall compliance were less likely to benefit from recruitment maneuvers than those with compliant chest walls [41]. Patients with ARDS who are ventilated with high tidal volumes or high levels of PEEP are less apt to derecruitment and may not exhibit a response to recruiting interventions [14, 24]. Because prone positioning recruits lung volume and reduces the anteroposterior intrathoracic pressure gradient, volume recruitment maneuvers may be less necessary. However, in the prone position the pressure required to achieve recruitment is lower and the effect is more sustained [21, 25].

The inspired oxygen fraction may affect lung recruitment, because of absoption atelectasis in situations where inspired oxygen fraction approaches 1.0. The recruitment effect may be rapidly lost in patients ventilated on 100% oxygen [42].

What we still need to know

The time course of response to recruitment maneuvers remains unclear. Lung mechanics in ARDS vary with time [43], and it remains unknown whether the recruitment response varies throughout the day or is related to changes in patient position or spontaneous ventilatory effort. Although a response is more likely early in the course of disease, these studies have only been performed at a single time period. Although the studies cited above have given some insight into identifying patients who may respond to recruitment maneuvers, this does not address the question of whether this intervention is beneficial in terms of reducing lung injury or mortality in this group.

Where does recruitment fit in a ventilatory strategy?

Lung volume recruitment procedures have a role to play as an adjunct to pressure-limited ventilatory strategies. Although clear evidence of benefit is lacking, recruitment maneuvers have been suggested to be of use in certain situations, which are described below.

First, lung recruitment maneuvers may be used to open nonaerated lung zones, particularly early in the course of disease in patients who are ventilated with low tidal volumes. In this situation the expected benefit is in improving oxygenation and preventing further lung injury. Multiple recruitment maneuvers may be needed to achieve a satisfactory response [44]. Adequate levels of PEEP are required to maintain the recruitment effect.

Second, lung recruitment maneuvers may aid in the choice of appropriate PEEP setting [34]. The response to recruitment, assessed by measuring oxygenation and lung compliance, can identify patients with extensive recruitable lung and those with a low recruitment potential. Patients in the latter group may require only relatively low levels of PEEP, in the range of 5–10 cmH2O. In patients with a clear response to a recruitment maneuver the PEEP level required to prevent derecruitment can be assessed by a decremental PEEP trial. Following the recruitment maneuver, PEEP is gradually reduced (e.g. 2 cmH2O every minute) while monitoring oxygen saturation continuously. The PEEP at which oxygen desaturation occurs is noted, and PEEP is set 2 cmH2O above this level following another recruitment maneuver.

Third, lung recruitment maneuvers may be used to recruit the lung after interventions associated with derecruitment, including ventilator disconnects and endotracheal suctioning [35].

What are the adverse effects of recruitment maneuvers?

Although recruitment procedures are generally well tolerated with few adverse effects, several potential complications should be anticipated. Because of the transient increase in intrathoracic pressure and consequent reduction in venous return, cardiac output may be impaired, producing hypotension – a complication that appears to be more common in those with poor chest wall compliance and limited oxygenation response from recruitment [41]. Generally, hypotension during the maneuver suggests relative volume depletion. A decrease in cerebral perfusion pressure has been noted, which may contraindicate this procedure in head injured patients [35]. Barotrauma, including pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax, has been described but the exact risk remains unclear. Because elevated pressure may alter the integrity of the alveolar–capillary membrane, increased bacterial translocation may occur [45]. Laboratory studies have suggested that partial recruitment may aggravate cytokine production in the lung. The atelectatic lung has little cytokine production, which may be markedly increased by inadequate recruitment or repeated derecruitment [46].

Conclusion

Current literature regarding the use of recruitment maneuvers during mechanical ventilation does not identify a clear beneficial role for this intervention, but pathophysiologic rationale and compelling laboratory and clinical data support an 'open lung' strategy in certain situations. Although we cannot be sure that a recruitment maneuver will improve outcome, there seems little harm in attempting this approach to improve oxygenation early in the course of patients with hypoxic respiratory failure. Those who respond may accrue the additional benefit of reduced ventilator-induced lung injury. It is essential to avoid doing harm, by monitoring for the potential adverse effects on cardiac output and barotrauma, and ensuring that the overriding ventilatory strategy is one of pressure limitation. Many questions remain, and we hope that some of these will be addressed by clinical studies that are currently in progress.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

= acute respiratory distress syndrome

- PEEP:

-

= positive end-expiratory pressure.

References

Hubmayr R: Perspective on lung injury and recruitment. A skeptical look at the opening and collapse story. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165: 1647-1653. 10.1164/rccm.2001080-01CP

Uhlig S, Ranieri M, Slutsky AS: Biotrauma hypothesis of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004, 169: 314-315.

Lachmann B: Open up the lung and keep the lung open. Intensive Care Med 1992, 18: 31.

Bond DM, McAloon J, Froese AB: Sustained inflations improve respiratory compliance during high-frequency oscillatory ventilation but not during large tidal volume positive-pressure ventilation in rabbits. Crit Care Med 1994, 22: 1269-1277.

Dos Santos CC, Slutsky AS: Mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury: a perspective. J App Physiol 2000, 89: 1645-1655.

Piacentini E, Villagra A, Lopez-Aguilar J, Blanch L: The implications of experimental and clinical studies of recruitment maneuvers in acute lung injury. Crit Care 2004, 8: 115-121. 10.1186/cc2364

Richard J-C, Maggiore S, Mercat A: Where are we with recruitment in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome? Curr Opin Crit Care 2003, 9: 22-27. 10.1097/00075198-200302000-00005

Puybasset L, Cluzel P, Gusman P: Regional distribution of gas and tissue in acute respiratory distress syndrome. I. Consequences for lung morphology. CT Scan ARDS Study Group. Intensive Care Med 2000, 26: 857-869. 10.1007/s001340051274

Mead J, Takashima T, Leith D: Stress distribution in lungs: a model of pulmonary toxicity. J Appl Physiol 1970, 28: 596-608.

Muscedere JG, Mullen JB, Gan K, Slutsky AS: Tidal ventilaton at low airway pressures can augment lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 149: 1327-1334.

Ranieri V, Suter P, Tortorella C, Tullio R, Dayer J, Brienza A, Bruno F, Slutsky A: Effect of mechanical ventilation on inflammatory mediators in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999, 282: 54-61. 10.1001/jama.282.1.54

Stewart TE, Meade MO, Cook DJ, Granton JT, Hodder RV, Lapinsky SE, Mazer CD, McLean RF, Rogovein TS, Schouten D, et al.: Evaluation of a ventilation strategy to prevent barotrauma in patients at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998, 338: 355-361. 10.1056/NEJM199802053380603

The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network: Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000, 342: 1301-1308. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801

Richard JC, Maggiore SM, Jonson B, Mancebo J, Lemaire F, Brochard L: Influence of tidal volume on alveolar recruitment. Respective role of PEEP and a recruitment maneuver. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 163: 1609-1613.

Gattinoni L, Pelosi P, Suter PM, Pedoto A, Vercesi P, Lissoni A: Acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease. Different syndromes? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 158: 3-11.

Crotti S, Mascheroni D, Caironi P, Pelosi P, Ronzoni G, Mondino M, Marini J, Gattinoni L: Recruitment and derecruitment during acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164: 131-140.

Rimensberger PC, Cox P, Frndova H, Bryan CH: The open lung during small tidal volume ventilation: concepts of recruitment and 'optimal' positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med 1999, 27: 1946-1952. 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00038

Van der Kloot TE, Blanch L, Youngblood AM, Weinert C, Adams A, Marini J, Shapiro R, Nahum A: Recruitment maneuvers in three experimental models of acute lung injury. Effect on lung volume and gas exchange. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161: 1485-1494.

Duggan M, McCaul CL, McNamara PJ, Engelberts D, Ackerley C, Kavanagh BP: Atelectasis causes vascular leak and lethal right ventricular failure in uninjured rat lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 167: 1633-1640. 10.1164/rccm.200210-1215OC

Marini JJ: Recruitment maneuvers to achieve an 'open lung': whether and how? Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1647-1648. 10.1097/00003246-200108000-00032

Lim CM, Jung H, Koh Y, Lee JS, Shim TS, Lee SD, Kim WS, Kim DS, Kim WD: Effect of alveolar recruitment maneuver in early acute respiratory distress syndrome according to antiderecruitment strategy, etiological category of diffuse lung injury, and body position of the patient. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: 411-418. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000048631.88155.39

Lapinsky SE, Aubin M, Mehta S, Boiteau P, Slutsky A: Safety and efficacy of a sustained inflation for alveolar recruitment in adults with respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med 1999, 25: 1297-1301.

Pelosi P, Cadringher P, Bottino N, Panigada M, Carrieri F, Riva E, Lissoni A, Gattinoni L: Sigh in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999, 159: 872-880.

Foti G, Cereda M, Sparacino M, De Marchi ME, Villa F, Pesenti A: Effects of periodic lung recruitment maneuvers on gas exchange and respiratory mechanics in mechanically ventilated ARDS patients. Intensive Care Med 2000, 26: 501-507. 10.1007/s001340051196

Pelosi P, Bottino N, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Panigada M, Gamberoni C, Colombo G, Bigatello LM, Gattinoni L: Sigh in supine and prone position during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 167: 521-527. 10.1164/rccm.200203-198OC

Brower RG, Morris A, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Hayden D, Thompson T, Clemmer T, Lanken PN, Schoenfeld D, ARDS Clinical Trials Network, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health: Effects of recruitment maneuvers in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with high positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: 2592-2597.

Meade MO, Guvatt GH, Cook DJ, Lapinsky SE, Hand L, Griffith L, Stewart TE: Physiologic randomized pilot study of a lung recruitment maneuver in acute lung injury [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165: A683.

Hickling KG: Best compliance during a decremental, but not incremental, positive end-expiratory pressure trial is related to open-lung positive end-expiratory pressure: a mathematical model of acute respiratory distress syndrome lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 163: 69-78.

Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, Kairalla RA, Deheinzelin D, Munoz C, Oliveira R, et al.: Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998, 338: 347-354. 10.1056/NEJM199802053380602

Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Morris A, Ancukiewicz M, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network: Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2004, 351: 327-336. 10.1056/NEJMoa032193

Mehta S: Lung volume recruitment. Curr Opin Crit Care 1998, 4: 6-15.

Lim CM, Koh Y, Park W, Chin JY, Shim TS, Lee SD, Kim WS, Kim DS, Kim WD: Mechanistic scheme and effect of 'extended sigh' as a recruitment maneuver in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a preliminary study. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1255-1260. 10.1097/00003246-200106000-00037

Engelmann L, Lachmann B, Petros S, Bohm S, Pilz U: ARDS: dramatic rises in arterial PO 2 with the "open lung" approach [abstract]. Crit Care 1997, Suppl 1: 54.

Marini JJ, Gattinoni L: Ventilatory management of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a consensus of two. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 250-255. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104946.66723.A8

Maggiore SM, Lellouche F, Pigeot J, Taille S, Deye N, Durrmeyer X, Richard JC, Mancebo J, Lemaire F, Brochard L: Prevention of endotracheal suctioning-induced alveolar derecruitment in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 167: 1215-1224. 10.1164/rccm.200203-195OC

Bein T, Kuhr LP, Bele S, Ploner F, Keyl C, Taeger K: Lung recruitment maneuver in patients with cerebral injury: effects on intracranial pressure and cerebral metabolism. Intensive Care Med 2002, 28: 554-558. 10.1007/s00134-002-1273-y

Richard JC, Maggiore SM, Mercat A: Clinical review: Bedside assessment of alveolar recruitment. Crit Care 2004, 8: 163-169. 10.1186/cc2391

Tusman G, Bohm SH, Vazquez de Anda GF, do Campo JL, Lachmann B: 'Alveolar recruitment strategy' improves arterial oxygenation during general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1999, 82: 8-13.

Dyhr T, Laursen N, Larsson A: Effects of lung recruitment maneuver and positive end-expiratory pressure on lung volume, respiratory mechanics and alveolar gas mixing in patients ventilated after cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002, 46: 717-725. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460615.x

Villagra A, Ochagavia A, Vatua S, Murias G, Del Mar Fernandez M, Lopez Aguilar J, Fernandez R, Blanch L: Recruitment maneuvers during lung protective ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165: 165-170.

Grasso S, Mascia L, Del Turco M, Malacarne P, Giunta F, Brochard L, Slutsky AS, Marco Ranieri V: Effects of recruiting maneuvers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with protective ventilatory strategy. Anesthesiology 2002, 96: 795-802. 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00005

Rothen HU, Sporre B, Engberg G, Wegenius G, Hogman M, Hedenstierna G: Influence of gas composition on recurrence of atelectasis after a reexpansion maneuver during general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1995, 82: 832-842. 10.1097/00000542-199504000-00004

Mehta S, Stewart TE, MacDonald R, Hallett D, Aubin M, Lapinsky SE, Slutsky AS: Temporal change, reproducibility, and interobserver variability in pressure-volume curves in adults with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2003, 21: 2118-2125. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069342.00360.9F

Fujino Y, Goddon S, Dolhnikoff M, Hess D, Amato MB, Kacmarek RM: Repetitive high-pressure recruitment maneuvers required to maximally recruit lung in a sheep model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1579-1586. 10.1097/00003246-200108000-00014

Cakar N, Akinci O, Tugrul S, Ozcan PE, Esen F, Eraksoy H, Cagatay A, Telci L, Nahum A: Recruitment maneuver: does it promote bacterial translocation? Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 2103-2106. 10.1097/00003246-200209000-00025

Chu EK, Whitehead T, Slutsky AS: Effects of cyclic opening and closing at low- and high-volume ventilation on bronchoalveolar lavage cytokines. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 168-174. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104203.20830.AE

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lapinsky, S.E., Mehta, S. Bench-to-bedside review: Recruitment and recruiting maneuvers. Crit Care 9, 60 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2934

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2934