Abstract

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) after cardiac surgery is associated with a high postoperative morbidity and mortality, but few predictors are known for the occurrence of the complication. This study evaluated whether elevated plasma levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) and S100A12 reflected impaired lung function in infants and young children after cardiac surgery necessitating cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).

Methods

Consecutive children younger than 3 years after cardiac surgery were prospectively enrolled and assigned to ALI and non-ALI groups, according to the American-European Consensus Criteria. Plasma concentrations of sRAGE and S100A12 were measured at baseline, before, and immediately after CPB, as well as 1 hour, 12 hours, and 24 hours after operation.

Results

Fifty-eight patients were enrolled and 16 (27.6%) developed postoperative ALI. Plasma sRAGE and S100A12 levels increased immediately after CPB and remained significantly higher in the ALI group even 24 hour after operation (P < 0.01). In addition, a one-way MANOVA revealed that the overall sRAGE and S100A12 levels were higher in the ALI group than in the non-ALI group immediately after CPB (P < 0.001). The multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the plasma sRAGE level immediately after CPB was an independent predictor for postoperative ALI (OR, 1.088; 95% CI, 1.011 to 1.171; P = 0.025). Increased sRAGE and S100A12 levels immediately after CPB were significantly correlated with a lower PaO2/FiO2 ratio (P < 0.01) and higher radiographic lung-injury score (P < 0.01), as well as longer mechanical ventilation time (sRAGEN: r = 0.405; P = 0.002; S100A12N: r = 0.322; P = 0.014), longer surgical intensive care unit stay (sRAGEN: r = 0.421; P = 0.001; S100A12N: r = 0.365; P = 0.005) and hospital stay (sRAGEN: r = 0.329; P = 0.012; S100A12N: r = 0.471; P = 0.001).

Conclusions

Elevated sRAGE and S100A12 levels correlate with impaired lung function, and sRAGE is a useful early biomarker of ALI in infants and young children undergoing cardiac surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative lung injury may occur in 12% to 50% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery necessitating cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) [1–4], and up to 20% of the patients need ventilation for more than 48 hours [5]. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) occurs in 2% of these cases, resulting a mortality of 15% to 50% [3, 4]. Children are more prone to acute lung injury (ALI) under the detrimental stimulation during cardiac surgery with CPB [6–8]. ALI/ARDS after CPB often leads to a prolonged length of hospital stay and increased therapeutic costs. Therefore, developing certain predictive biomarker for CPB-related ALI/ARDS in infants and young children undergoing cardiac surgery would be of great help for early diagnosis and efficient therapeutic decision making.

The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that acts as a multiligand receptor and progression factor in propagating the inflammatory response [9, 10]. RAGE is expressed at a high level in the basal surface of alveolar type I cells, and its expression is upregulated under inflammatory conditions [9, 11, 12]. Soluble RAGE (sRAGE) is the extracellular form of RAGE and is produced by either cleaving the membrane by proteolysis or removing the transmembrane region via alternative splicing [12]. Increasing evidence suggests that local and circulating levels of sRAGE are promising as biomarkers of pulmonary tissue damage. The sRAGE concentration has been reported to be dramatically higher in pulmonary edema fluid and plasma from adult patients with ALI/ARDS, which were caused by sepsis, trauma, or primary pneumonia [13, 14]. Furthermore, increased plasma sRAGE levels are significantly correlated with the severity and clinical outcome of ALI/ARDS [15, 16].

S100A12 is a member of the S100 family of calcium-binding proteins, which is a newly identified extracellular prototypic ligand of RAGE [17, 18]. S100A12 expression may reflect neutrophil activation and contribute to pulmonary inflammation and endothelial activation via binding to RAGE [14, 18]. Blocking the interaction of S100A12 and RAGE results in improvement of inflammation in multiple experimental models [18, 19]. Wittkowski et al. [14] found that compared with healthy controls, patients with ARDS caused by pneumonia or peritonitis had significantly enhanced S100A12 expression in pulmonary tissue and higher S100A12 concentrations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

Plasma sRAGE was recently reported to be a sensitive and rapid marker of lung distress after elective coronary artery bypass grafting in a study of 20 adult patients [20]. Additionally, Kikkawa and colleagues [21] found that sepsis patients who developed postoperative ALI had higher S100A12 levels compared with controls. Initial studies are promising. However, it is not clear whether these findings could extend to younger children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB.

This pilot study aimed to observe the kinetics of plasma sRAGE and S100A12 in infants and young children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB and to investigate whether plasma sRAGE and S100A12 levels are associated with the occurrence and severity of ALI after cardiac surgery.

Materials and methods

Study population

This prospective study was conducted at a university children's hospital located in eastern China. The study protocols were approved by the hospital ethics committee (Medical Ethical Committee of the Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University), and informed consents were signed by supervisors of the patients. Children who were younger than 3 years and scheduled for cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease (CHD) were consecutively enrolled. The included patients had stable clinical conditions for at least 2 months. Patients were excluded if they were premature, had abnormal liver or renal function, had major chromosomal abnormalities, showed pulmonary inflammation before the surgery, had pulmonary edema due to cardiac dysfunction, needed extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support after the operation, died because of cardiac dysfunction, or refused to participate in the study.

Data collection and definitions

During the surgical procedure, all patients underwent routine hemodynamic and blood gas surveillance. Anesthesia, the CPB procedure, and weaning from mechanical ventilation (MV) in the surgical Intensive Care Unit (ICU) were all performed by using standard protocols, as shown in additional material in detail [Additional file 1].

Demographic and preoperative data were collected, including the patient's gender, age, weight, pulse oximetry saturation (SpO2), Risk Adjusted Classification for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1), ultrafiltrate volume, CPB time and operation time, duration of MV, and the ratio of fraction of inspired oxygen to oxygen pressure (PaO2/FiO2). A bedside chest radiograph was taken every day after surgery. A structured tutorial was used to establish consensus in the interpretation of radiographs for radiographic lung-injury scores (LISs) [16, 22]. Echocardiography was performed routinely to evaluate the cardiac function after surgery and at any time if necessary. The left ventricular function was evaluated by the ejection fraction (EF). The North American-European Consensus Criteria were used to categorize the patients into the ALI group and non-ALI group. In brief, this criterion includes the acute onset of bilateral alveolar infiltrates seen on a chest radiograph, a PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 300, and the absence of cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE) [23]. CPE was identified when the pulmonary arterial occlusion pressure was > 18 mm Hg or by the presence of at least two of the following: central venous pressure > 14 mm Hg, left ventricular EF < 45%, systemic hypertension, or volume overload. Patients with CPE were excluded; CPE was diagnosed by two independent attending cardiac intensivists, who were blinded to the group of ALI patients. In addition, the both groups were followed up for ICU length of stay (LOS) and hospital LOS.

Determination of sRAGE and S100A12 in plasma

For each patient, 2 ml of fresh blood was drawn into a vacuum tube containing EDTA at the following time points: before operation, before CPB, after CPB, 1 hour, 12 hours, and 24 hours after operation. After being centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C, the plasma was divided into aliquots and frozen at -80°C until assay.

sRAGE and S100A12 levels were measured by using the commercially available ELISA kits (sRAGE, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; S100A12, Cirulex; Cyclex Co. Ltd, Nagano, Japan), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The plasma total protein levels were determined with an autobiochemistry analyzer and used for sRAGE and S100A12 normalization (sRAGEN, sRAGE normalized for total protein; S100A12N, S100A12 normalized for total protein). Laboratory staffs were blinded to the ALI patients, and investigators involved in the interpretation of ALI were blinded to sRAGE and S100A12 levels.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were tested for normal distribution with the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables were presented as mean values and standard deviations if normally distributed, and otherwise, as median values (interquartile range). The Student t test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to determine the significance of variable differences between the two groups. The χ2 test or Fisher Exact test were used to compare categorical data as appropriate. A multivariate analysis of variance procedure (MANOVA) was used to assess whether a significant difference remained in the overall assessment of sRAGE and S100A12 levels between the two groups. A Pearson or Spearman correlation test was performed to determine the correlation between biomarker (sRAGE and S100A12) data and clinical parameters (CPB time, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, MV time, and ICU and hospital LOS). Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was computed, and area under the curve (AUC) was used to evaluate how well the biomarkers diagnose ALI. A stepwise logistic regression model was used to determine the independent risk factor for ALI after CPB. The multivariate variables included age, weight, sex, CPB time, operation time, and the concentration of sRAGEN and S100A12N immediately after CPB. These variables were then entered into a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis to determine the factors significantly associated with the PaO2/FiO2 ratio within the first 2 days. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS (SPSS 16.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study population

From May 1 to June 30, 2011, of the 71 consecutive patients younger than 3 years who underwent cardiac surgery, 58 (81.7%) fulfilled the inclusion criteria, which included 27 (46.6%) infants. Thirteen patients were excluded for the following reasons: pneumonia before surgery (eight patients), liver insufficiency (one patient), prematurity (two patients), receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation owing to low-cardiac-output syndrome (one patient), and absence of written informed consent (one patient). Finally, among the 58 patients, 16 (27.6%) developed ALI. The characteristics and cardiac-lesion types of the enrolled patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Perioperative sRAGE and S100A12 concentrations

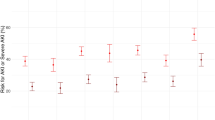

Plasma sRAGE and S100A12 concentrations are shown in Table 3, both as absolute values (picograms per milliliter) and normalized values (picograms per milligram total protein). The latter values were needed because total plasma protein concentration decreased dramatically during CPB (P < 0.001). Plasma levels of sRAGE and S100A12 increased significantly immediately after CPB (P < 0.001), and the elevated levels were correlated with the CPB time (Figure 1; sRAGE: r = 0.303; P = 0.021; sRAGEN: r = 0.305; P = 0.02; S100A12: r = 0.371; P = 0.004; S100A12N: r = 0.376; P = 0.004). Therefore, the normalized values (sRAGEN and S100A12N, respectively) immediately after CPB were used for subsequent analysis. Twenty-four hours after operation, the levels of sRAGE decreased lower than the baseline levels (P < 0.05), whereas S100A12 levels remained higher (P < 0.001).

Plasma sRAGE as a predictor for acute lung injury

The post-CPB ALI development not only was associated with age, weight, operation time, and CPB time (P < 0.01) (Table 1), but also was significantly associated with the levels of sRAGE and S100A12 immediately after CPB (Figure 2; P < 0.01). In addition, the levels of sRAGE and S100A12 were kept higher in the ALI group than those in non-ALI group at 24 hours after operation (Figure 2; P < 0.01). The one-way MANOVA analysis revealed that ALI patients had significantly increased overall biomarkers of sRAGE and S100A12, as compared with the non-ALI ones, both immediately after CPB and 24 hours after operation (F = 29.06; P < 0.001 and F = 11.72; P < 0.001, respectively).

In the ROC analysis, the AUC of sRAGEN and S100A12N levels immediately after CPB for ALI were 0.775 (95% CI, 0.626 to 0.924) and 0.714 (95% CI, 0.539 to 0.889), respectively. At a cutoff value of 54 pg/mg, sRAGEN had a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 91% for diagnosis of ALI after CPB, whereas at a cutoff of 4,326.5 pg/mg, S100A12N had a sensitivity of 58% and a specificity of 100% (Figure 3). The logistic regression analysis, which included age, weight, sex, operation time, and CPB time, as well as S100A12N and sRAGEN levels immediately after CPB, revealed that the independent risk factors for the occurrence of ALI were sRAGEN (OR, 1.088; 95% CI, 1.011 to 1.171; P = 0.025), age (OR, 0.681; 95% CI, 0.528 to 0.879; P = 0.003), and CPB time (OR, 1.070; 95% CI, 1.008 to 1.136; P = 0.026).

Receiver operating characteristic curves displaying the ability of plasma levels of sRAGE N and S100A12 N to predict the occurrence of ALI. The AUCs of sRAGEN and S100A12N for ALI were 0.775 (95% CI, 0.626 to 0.924) and 0.714 (95% CI, 0.539 to 0.889), respectively. ALI, acute lung injury; AUC, area under the curve.

Plasma sRAGE and S100A12 predict the severity of acute lung injury and clinical outcomes

Higher levels of plasma sRAGEN and S100A12N immediately after CPB were significantly associated with more-severe ALI, as reflected by the measurement of pulmonary physiology, including the PaO2/FiO2 ratio on the first 2 days (Figure 4A and 4B for the first day; sRAGEN: r = -0.404; P = 0.002; S100A12N: r = -0.56; P < 0.001; Figure 4C and 4D for the second day: sRAGEN: r = -0.448; P < 0.001; S100A12N: r = -0.489; P < 0.001), as well as radiographic LIS (Figure 4E and 4F; P < 0.01). After adjusting for age, weight, sex, operation time, and CPB time in a multiple linear regression model, we found that sRAGEN but not S100A12N levels immediately after CPB were independently associated with the PaO2/FiO2 ratio on the second day (B = -2.153; 95% CI, -0.559 to -3.747; P = 0.009); however, none of them was associated with the ratio within 24 hours after surgery.

Likewise, elevated sRAGEN and S100A12N levels were correlated with longer MV time (Figure 5A and 5B; sRAGEN: r = 0.405; P = 0.002; S100A12N: r = 0.322; P = 0.014), surgical ICU LOS (Figure 5C and 5D; sRAGEN: r = 0.421; P = 0.001; S100A12N: r = 0.365; P = 0.005) and hospital LOS (Figure 5E and 5F; sRAGEN: r = 0.329; P = 0.012; S100A12N: r = 0.471; P = 0.001).

Discussion

In this prospective pilot study of the kinetics of plasma sRAGE and S100A12 levels in infants and young children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, we found that plasma concentrations of sRAGE and S100A12 remarkably increased immediately after CPB. The elevated levels were correlated with the severity of ALI and clinical outcomes of cardiac surgery with CPB and plasma sRAGE was a reliable early predictor for the occurrence of ALI after cardiac surgery.

Uniquely, RAGE is expressed at remarkably high basal levels in lung tissues [9, 11, 12], suggesting that it holds important functions in both pulmonary physiology and numerous pathologic states [9, 12]. The normal values of sRAGE were reported to range from 500 to 1,250 pg/ml in healthy volunteers [20, 21, 24, 25]. In addition, no significant difference was found in normal plasma sRAGE levels among various ages and in baseline levels with respect to the cause of lung injury, such as aspiration pneumonia, and to coexisting conditions, such as diabetes, end-stage renal disease, essential hypertension, or other vascular diseases [13]. Previous studies provided supportive evidence that the primary source of plasma sRAGE in ALI/ARDS patients was alveolar type I cells [11–13, 24], and sRAGE served as a marker of alveolar epithelial injury [15, 16, 24]. As expected, in the current study, we found that the plasma levels of sRAGE were significantly higher in the ALI group than in the non-ALI group immediately after CPB. After adjusting the ALI-related variants, sRAGE remained as an independent risk factor for ALI development. Furthermore, we found the sRAGE levels were related with the impaired lung function, such as lower PaO2/FiO2 ratio and higher radiographic LIS. These findings suggested that plasma sRAGE levels may serve as a reliable quantitative predictor for the development of post-CPB ALI in infants and young children. Because plasma was diluted during CPB, the normalized plasma sRAGE and S100A12 concentrations were used to define the cut-off values (sRAGE, 54 pg/mg; S100A12, 4,326.5 pg/mg) in our study. Nevertheless, the cut-off value should be used with caution to diagnose ALI in a clinical setting, because the defined abnormal sRAGE or S100A12 levels were unequal among different studies in different patients [20, 21, 24, 25]. Unfortunately, to date, only a few studies exist on sRAGE and S100A12, which were always based on small number of patients. Hence, a larger-cohort validation study is needed to verify these results in future.

Previous studies have shown that the elevated circulation levels of sRAGE after onset of ALI/ARDS soon decreased to lower levels [13, 14, 17, 18]. Interestingly, we found similar kinetics of plasma sRAGE during CPB in children, to those in adult patients receiving coronary artery bypass grafting [20]. One possible explanation for this decrement is the reoxygenation resulting from reperfusion of the lung after CPB, because Lizotte et al. [26] reported that hyperoxic exposures lead to a loss of sRAGE in the neonatal rat lung. In addition, a great number of activated neutrophils during extracorporeal circulation may explain the decreasing sRAGE levels [27]. sRAGE is known to have multiple protease-sensitive sites, so it might be degraded by neutrophil-derived proteolytic enzymes [28].

Infiltration of activated neutrophils is an important hallmark of ALI [29]; therefore more neutrophils in ALI may account for the high levels of S100A12 in the ALI group. Although neutrophils and their secretory products play important roles in the pulmonary inflammation, such as ALI, they are a rather unspecific surrogate for lung-tissue injury [29–31], which may contribute to the disassociation of plasma levels of S100A12 with the occurrence and the severity of post-CPB ALI in the logistic analysis and the multiple linear regression analysis.

In addition, the present study found that both plasma levels of sRAGE and S100A12 immediately after CPB were positively correlated with the duration of MV, surgical ICU LOS, and hospital LOS, and that sRAGE showed an independent association with the PaO2/FiO2 ratio on the second day. Although speculative, the following reasons might explain these correlations. In ALI/ARDS patients, Mauri et al. [15] reported that the first-day plasma sRAGE levels were correlated with the release of CRP and pentraxin 3 (PTX3) in the circulation [15], which promoted the coagulation/fibrinolysis dysfunction and organ failures [15, 32]. RAGE interacts with leukocyte Mac-1 integrin, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and CD11c/CD18 to facilitate inflammatory cell recruitment [33, 34]. Attraction of leukocytes to an inflammation site is additionally augmented by interaction with RAGE ligands such as S100A12 [10, 14, 18, 32]. Furthermore, interaction of RAGE and S100A12 causes production of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 [12, 21], which induced increased lung cell damage and vascular permeability [34, 35]. Taken together, RAGE and S100A12 contribute to more severe and prolonged inflammation in the lung and damage of the alveolar capillary barrier with increased lung water content and impaired oxygenation, resulting in longer MV support and more critical care in the SICU after cardiac surgery. There was no doubt that the S100A12-RAGE axis played an important role in the development of ALI after cardiac surgery with CPB. Because several single nuclear polymorphisms of the RAGE gene were recently found to affect the expression of sRAGE and associate with lung function in pathologic states [36–38], it should be emphasized that genetic variation of RAGE must be considered in further studies.

Limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. Although the kinetics of plasma sRAGE levels in this study is consistent with that in a published study [20], our findings were based on a small number of patients in a single center, which might limit the application of these findings to other institutions. Furthermore, we enrolled the patients undergoing surgery for CHD in the absence of relevant comorbidities and particularly of known lung disease. Therefore, we are not sure whether the sRAGE and S100A12 changes would be the same in the presence of previous lung diseases. Because children often have pneumonias before cardiac operations, future studies must confirm this.

Interestingly, Jabaudon et al. [13] reported that sRAGE levels in ALI/ARDS were not influenced by the presence of RAGE-related diseases such as sepsis, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, coronary artery disease, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer disease, and essential hypertension.

Third, the traditional inflammatory cytokines were not measured in this study. However, none of them was a specific biomarker for post-CPB ALI, although they were found to change perioperatively. In addition, in vitro study showed that the induction of S100A12 was more prominent than other cytokines, such as IL-8 [14], suggesting that the S100A12-RAGE axis may be more important in the CPB-induced inflammatory response.

Conclusions

We found that plasma sRAGE acts as a reliable early biomarker of ALI after cardiac surgery with CPB in infants and young children. The plasma levels of sRAGE and S100A12 are associated with lung function and clinical outcomes after CPB. These data may indicate that RAGE is a mediator of lung injury in patients after cardiac surgery and not merely a maker of disease. Insight into the role of the ligand-RAGE axis in the post-cardiac surgery inflammatory response holds the potential for better understanding of ALI induced by CPB.

Key messages

-

Early identification of the occurrence of acute lung injury (ALI) would facilitate efficient therapeutic decision making in infants and young children after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).

-

Plasma sRAGE and S100A12 levels increased after CPB, and the plasma levels of sRAGE immediately after CPB showed high predictive values for the development of ALI in infants and young children after cardiac surgery necessitating CPB.

-

Increased sRAGE and S100A12 levels immediately after CPB significantly reflected the severity of ALI and are correlated with longer mechanical ventilation time, surgical ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay.

-

Further studies are required to confirm the value of sRAGE in predicting ALI after cardiac surgery with CPB in a larger population.

Abbreviations

- ALI:

-

acute lung injury

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CHD:

-

congenital heart disease

- CPB:

-

cardiopulmonary bypass

- MV:

-

mechanical ventilation

- LIS:

-

lung-injury score

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- sRAGE:

-

soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products

- RACHS-1:

-

risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease.

References

Apostolakis E, Filos KS, Koletsis E, Dougenis D: Lung dysfunction following cardiopulmonary bypass. J Card Surg 2010, 25: 47-55. 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00823.x

Milot J, Perron J, Lacasse Y, Létourneau L, Cartier PC, Maltais F: Incidence and predictors of ARDS after cardiac surgery. Chest 2001, 119: 884-888. 10.1378/chest.119.3.884

Verheij J, van Lingen A, Raijmakers PG, Spijkstra JJ, Girbes AR, Jansen EK, van den Berg FG, Groeneveld AB: Pulmonary abnormalities after cardiac surgery are better explained by atelectasis than by increased permeability oedema. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005, 49: 1302-1310. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00831.x

Raijmakers PG, Groeneveld AB, Schneider AJ, Teule GJ, van Lingen A, Eijsman L, Thijs LG: Transvascular transport of 67Ga in the lungs after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Chest 1993, 104: 1825-1832. 10.1378/chest.104.6.1825

Clark SC: Lung injury after cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion 2006, 21: 225-228. 10.1191/0267659106pf872oa

Santos AR, Heidemann SM, Walters HL, Delius RE: Effect of inhaled corticosteroid on pulmonary injury and inflammatory mediator production after cardiopulmonary bypass in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2007, 8: 465-469. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000282169.11809.80

Komai H, Naito Y, Okamura Y: Dextran sulfate as a leukocyte-endothelium adhesion molecule inhibitor of lung injury in pediatric open-heart surgery. Perfusion 2005, 20: 77-82. 10.1191/0267659105pf788oa

Shi S, Zhao Z, Liu X, Shu Q, Tan L, Lin R, Shi Z, Fang X: Perioperative risk factors for prolonged mechanical ventilation following cardiac surgery in neonates and young infants. Chest 2008, 134: 768-774. 10.1378/chest.07-2573

Creagh-Brown BC, Quinlan GJ, Evans TW, Burke-Gaffney A: The RAGE axis in systemic inflammation, acute lung injury and myocardial dysfunction: an important therapeutic target? Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 1644-1656. 10.1007/s00134-010-1952-z

Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM: The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest 2001, 108: 949-955.

Shirasawa M, Fujiwara N, Hirabayashi S, Ohno H, Iida J, Makita K, Hata Y: Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I lung alveolar cells. Genes Cells 2004, 9: 165-174. 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00712.x

Buckley ST, Ehrhardt C: The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and the lung. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010, 2010: 917108.

Jabaudon M, Futier E, Roszyk L, Chalus E, Guerin R, Petit A, Mrozek S, Perbet S, Cayot-Constantin S, Chartier C, Sapin V, Bazin JE, Constantin JM: Soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end products is a marker of acute lung injury but not of severe sepsis in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 480-488. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206b3ca

Wittkowski H, Sturrock A, van Zoelen MA, Viemann D, van der Poll T, Hoidal JR, Roth J, Foell D: Neutrophil-derived S100A12 in acute lung injury and respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 1369-1375. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000262386.32287.29

Mauri T, Masson S, Pradella A, Bellani G, Coppadoro A, Bombino M, Valentino S, Patroniti N, Mantovani A, Pesenti A, Latini R: Elevated plasma and alveolar levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts are associated with severity of lung dysfunction in ARDS patients. Tohoku J Exp Med 2010, 222: 105-112. 10.1620/tjem.222.105

Calfee CS, Ware LB, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Wickersham N, Matthay MA, the NHLBI ARDS Network: Plasma receptor for advanced glycation end products and clinical outcomes in acute lung injury. Thorax 2008, 63: 1083-1089. 10.1136/thx.2008.095588

Pietzsch J, Hoppmann S: Human S100A12: a novel key player in inflammation? Amino Acids 2009, 36: 381-389. 10.1007/s00726-008-0097-7

Hofmann MA, Drury S, Fu C, Qu W, Taguchi A, Lu Y, Avila C, Kambham N, Bierhaus A, Nawroth P, Neurath MF, Slattery T, Beach D, McClary J, Nagashima M, Morser J, Stern D, Schmidt AM: RAGE mediates a novel proinflammatory axis: a central cell surface receptor for S100/calgranulin polypeptides. Cell 1999, 97: 889-901. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80801-6

Liliensiek B, Weigand MA, Bierhaus A, Nicklas W, Kasper M, Hofer S, Plachky J, Gröne HJ, Kurschus FC, Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Martin E, Schleicher E, Stern DM, Hämmerling G G, Nawroth PP, Arnold B: Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) regulates sepsis but not the adaptive immune response. J Clin Invest 2004, 113: 1641-1650.

Agostoni P, Banfi C, Brioschi M, Magrì D, Sciomer S, Berna G, Brambillasca C, Marenzi G, Sisillo E: Surfactant protein B and RAGE increases in the plasma during cardiopulmonary bypass: a pilot study. Eur Respir J 2011, 37: 841-847. 10.1183/09031936.00045910

Kikkawa T, Sato N, Kojika M, Takahashi G, Aoki K, Hoshikawa K, Akitomi S, Shozushima T, Suzuki K, Wakabayashi G, Endo S: Significance of measuring S100A12 and sRAGE in the serum of sepsis patients with postoperative acute lung injury. Dig Surg 2010, 27: 307-312. 10.1159/000313687

Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR: An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988, 138: 720-723.

Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R: The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 149: 818-824.

Kim JK, Park S, Lee MJ, Song YR, Han SH, Kim SG, Kang SW, Choi KH, Kim HJ, Yoo TH: Plasma levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) and proinflammatory ligand for RAGE (EN-RAGE) are associated with carotid atherosclerosis in patients with peritoneal dialysis. Atherosclerosis 2012, 20: 208-214.

Bopp C, Hofer S, Weitz J, Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP, Martin E, Büchler MW, Weigand MA: sRAGE is elevated in septic patients and associated with patients outcome. J Surg Res 2008, 147: 79-83. 10.1016/j.jss.2007.07.014

Lizotte PP, Hanford LE, Enghild JJ, Nozik-Grayck E, Giles BL, Oury TD: Developmental expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) and its response to hyperoxia in the neonatal rat lung. BMC Dev Biol 2007, 7: 15. 10.1186/1471-213X-7-15

Sukkar MB, Wood LG, Tooze M, Simpson JL, McDonald VM, Gibson PG, Wark PA: Soluble RAGE is deficient in neutrophilic asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2012, 39: 721-729. 10.1183/09031936.00022011

Kumano-Kuramochi M, Ohnishi-Kameyama M, Xie Q, Niimi S, Kubota F, Komba S, Machida S: Minimum stable structure of the receptor for advanced glycation end product possesses multi ligand binding ability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 386: 130-134. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.142

Grommes J, Soehnlein O: Contribution of neutrophils to acute lung injury. Mol Med 2011, 17: 293-307.

Goodman RB, Pugin J, Lee JS, Matthay MA: Cytokine-mediated inflammation in acute lung injury. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2003, 14: 523-535. 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00059-5

Massoudy P, Zahler S, Becker BF, Braun SL, Barankay A, Meisner H: Evidence for inflammatory responses of the lungs during coronary artery bypass grafting with cardiopulmonary bypass. Chest 2001, 119: 31-36. 10.1378/chest.119.1.31

Mauri T, Coppadoro A, Bellani G, Bombino M, Patroniti N, Peri G, Mantovani A, Pesenti A: Pentraxin 3 in acute respiratory distress syndrome: an early marker of severity. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 2302-2308. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181809aaf

Chavakis T, Bierhaus A, Al-Fakhri N, Schneider D, Witte S, Linn T, Nagashima M, Morser J, Arnold B, Preissner KT, Nawroth PP: The pattern recognition receptor (RAGE) is a counterreceptor for leukocyte integrins: a novel pathway for inflammatory cell recruitment. J Exp Med 2003, 198: 1507-1515. 10.1084/jem.20030800

Adembri C, Kastamoniti E, Bertolozzi I, Vanni S, Dorigo W, Coppo M, Pratesi C, De Gaudio AR, Gensini GF, Modesti PA: Pulmonary injury follows systemic inflammatory reaction in infrarenal aortic surgery. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1170-1177. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000124875.98492.11

Worrall NK, Chang K, LeJeune WS, Misko TP, Sullivan PM, Ferguson TB Jr, Williamson JR: TNF-alpha causes reversible in vivo systemic vascular barrier dysfunction via NO-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol 1997, 273: H2565-H2574.

Repapi E, Sayers I, Wain LV, Burton PR, Johnson T, Obeidat M, Zhao JH, Ramasamy A, Zhai G, Vitart V, Huffman JE, Igl W, Albrecht E, Deloukas P, Henderson J, Granell R, McArdle WL, Rudnicka AR, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Barroso I, Loos RJ, Wareham NJ, Mustelin L, Rantanen T, Surakka I, Imboden M, Wichmann HE, Grkovic I, Jankovic S, Zgaga L, et al.: Genome-wide association study identifies five loci associated with lung function. Nat Genet 2010, 42: 36-44. 10.1038/ng.501

Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, Gharib SA, Loehr LR, Marciante KD, Franceschini N, van Durme YM, Chen TH, Barr RG, Schabath MB, Couper DJ, Brusselle GG, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM, Rotter JI, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Punjabi NM, Rivadeneira F, Morrison AC, Enright PL, North KE, Heckbert SR, Lumley T, Stricker BH, O'Connor GT, London SJ: Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet 2010, 42: 45-52. 10.1038/ng.500

Soler Artigas M, Wain LV, Repapi E, Obeidat M, Sayers I, Burton PR, Johnson T, Zhao JH, Albrecht E, Dominiczak AF, Kerr SM, Smith BH, Cadby G, Hui J, Palmer LJ, Hingorani AD, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, Ebrahim S, Smith GD, Barroso I, Loos RJ, Wareham NJ, Cooper C, Dennison E, Shaheen SO, Liu JZ, Marchini J, Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD) Respiratory Study Team, ahgam S, Naluai AT, Olin AC, Karrasch S, Heinrich J, Schulz H, McKeever TM, Pavord ID, Heliövaara M, Ripatti S, Surakka I, Blakey JD, Kähönen M, Britton JR, Nyberg F, Holloway JW, Lawlor DA, Morris RW, James AL, Jackson CM, Hall IP, Tobin MD, SpiroMeta Consortium: Effect of five genetic variants associated with lung function on the risk of chronic obstructive lung disease, and their joint effects on lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 184: 786-795. 10.1164/rccm.201102-0192OC

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Health Bureau of Zhejiang Provincial (2012ZDA031) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Xiang-Ming Fang: 30825037) and the National Science and Technology Plan Projects (2012BAI04B05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

XWL, QXC, QS, and XMF contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the article for important content. XWL, SSS, and ZS contributed to data collection, analysis, and interpretation and to drafting of the manuscript. XWL, QXC, SSS, ZS, RL, LHT, JGY, QS, and XMF contributed to data analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the article for important content. All authors read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2011_597_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Standard protocols for anesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass, and weaning from mechanical ventilation. Additional file 1 is the standard protocols for anesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass, and weaning from mechanical ventilation, which were used in all patients. (DOC 30 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Chen, Q., Shi, S. et al. Plasma sRAGE enables prediction of acute lung injury after cardiac surgery in children. Crit Care 16, R91 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11354

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11354