Abstract

Background

Data from interventional trials of systemic anticoagulation for sepsis inconsistently suggest beneficial effects in case of acute lung injury (ALI). Severe systemic bleeding due to anticoagulation may have offset the possible positive effects. Nebulization of anticoagulants may allow for improved local biological availability and as such may improve efficacy in the lungs and lower the risk of systemic bleeding complications.

Method

We performed a systematic review of preclinical studies and clinical trials investigating the efficacy and safety of nebulized anticoagulants in the setting of lung injury in animals and ALI in humans.

Results

The efficacy of nebulized activated protein C, antithrombin, heparin and danaparoid has been tested in diverse animal models of direct (for example, pneumonia-, intra-pulmonary lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-, and smoke inhalation-induced lung injury) and indirect lung injury (for example, intravenous LPS- and trauma-induced lung injury). Nebulized anticoagulants were found to have the potential to attenuate pulmonary coagulopathy and frequently also inflammation. Notably, nebulized danaparoid and heparin but not activated protein C and antithrombin, were found to have an effect on systemic coagulation. Clinical trials of nebulized anticoagulants are very limited. Nebulized heparin was found to improve survival of patients with smoke inhalation-induced ALI. In a trial of critically ill patients who needed mechanical ventilation for longer than two days, nebulized heparin was associated with a higher number of ventilator-free days. In line with results from preclinical studies, nebulization of heparin was found to have an effect on systemic coagulation, but without causing systemic bleedings.

Conclusion

Local anticoagulant therapy through nebulization of anticoagulants attenuates pulmonary coagulopathy and frequently also inflammation in preclinical studies of lung injury. Recent human trials suggest nebulized heparin for ALI to be beneficial and safe, but data are very limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

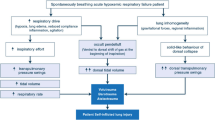

Pulmonary coagulopathy is intrinsic to acute lung injury (ALI). Indeed, both microvascular thrombi and alveolar fibrin depositions are hallmarks of ALI, irrespective of its cause [1–5]. The extent of pulmonary coagulopathy depends on the severity of ALI [1] and is clearly linked to the outcome of ALI [6–9]. Pulmonary coagulopathy with ALI resembles systemic coagulopathy with sepsis [4], and is characterized by activated coagulation, attenuation of fibrinolysis, and enhanced breakdown and/or decreased production of natural anticoagulants (Figure 1) [4, 10, 11]. Extensive cross-talk between coagulation and inflammation may further inflame the lungs [3]. Indeed, activated coagulation factors may initiate or exaggerate injury [12–14], impairing alveolar aeration and perfusion [15], and promoting fibrosis [16].

Schematic and simplified presentation of coagulation, fibrinolysis and anticoagulant pathways. The coagulation cascade is started through activation of tissue factor (TF)-factor VII (FVIIa) complex. Several coagulation factors accelerate the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin. Activated protein C (APC) can inactivate coagulation factors Va and VIIIa. Antithrombin (AT) serves to block the action of multiple coagulation factors (for example, Xa and IIa). Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) inhibits stepwise the activation of coagulation factors. The fibrinolytic system is designed to degrade clots and fibrin degradation products (FDP) are formed. The main inhibitor of the plasminogen activators is plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1). +: stimulating effect; -: inhibiting effect. Adapted and modified from Tuinman et al. [59].

Clinical trials inconsistently suggest beneficial effects of systemic anticoagulants in patients with ALI. Results from the PROWESS trial suggested patients with a pulmonary cause of their sepsis to benefit more from systemic anticoagulation with recombinant human (rh)-activated protein C (APC) than patients with sepsis from another source [17–19]. A recent clinical trial of patients with ALI even showed decreased pulmonary dead-space fraction with infusion of rh-APC, although this was not associated with an improved clinical outcome [20]. Notably, rh-APC has been withdrawn from the market, as the recent PROWESS-SHOCK trials showed no benefit from rh-APC in patient with septic shock [21]. Neither infusion of antithrombin (AT) nor infusion of rh-tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) has been found to improve outcome in sepsis [22, 23]. Infusion of AT, however, was found to prevent new pulmonary dysfunction [24]. Infusion of rh-TFPI was suggested to improve survival of patients with a community-acquired pneumonia [25] but failed to improve outcome of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia in the recent CAPTIVATE trial [26]. Finally, post hoc analysis of four large clinical trials of patients with sepsis suggested infusion of low-dose heparin to improve survival, although unintended pitfalls may not have been accounted for [27]. However, one recent clinical trial showed no effect on survival with infusion of unfractioned heparin [28].

High pulmonary concentrations of an anticoagulant may be necessary to have any effect on pulmonary coagulation, maybe higher than achievable with systemic treatment. Similar to systemic antimicrobial therapy for pneumonia, with which antimicrobial agents penetrate in dissimilar amounts into the lung [29], it could be argued that anticoagulants may not penetrate into lung tissue adequately to have a local effect. A major concern is the association between systemic anticoagulation and the high incidence of serious bleeding complications in patients with sepsis, which at times could be life-threatening [17, 22, 23, 30, 31]. With higher systemic dosages, possibly necessary to have sufficiently high concentrations in the lung, without doubt the incidence of bleedings would rise.

Local administration of anticoagulants, through nebulization, may allow for higher pulmonary concentrations while, at the same time, preventing systemic bleedings. To test the hypothesis whether nebulization of anticoagulants attenuates pulmonary coagulation without having systemic side-effects, we searched the literature for preclinical studies and human trials of nebulized anticoagulants in the context of lung injury in animals and ALI in humans. We aimed to search for any beneficial and harmful effects of nebulized anticoagulants.

Materials and methods

Data sources

To identify relevant manuscripts on local anticoagulation in the setting of lung injury in animals and ALI in humans, two search strategies were followed. First, an electronic search in Medline and Embase databases was conducted. Second, the reference lists of retrieved papers were screened for potentially important papers. The search was limited to papers published from 1980 until now, and papers written in the English language.

Keywords

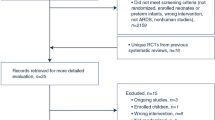

The Medline database was used to identify medical subject headings (MeSH) to select search terms. In addition to MeSH terms, also free text words were used. Search terms referred to aspects of the condition ('acute lung injury' (ALI), 'acute respiratory distress syndrome' (ARDS)) as well as related conditions ('pneumonia', sepsis', and 'ventilator-induced lung injury' (VILI)). In addition, we searched on the intervention ('nebulized', 'vaporized', and 'aerosolized'), and anticoagulant agents ('APC', 'AT', 'TFPI', 'heparin' and 'danaparoid'). We chose to limit the search of agents to those that have been tested in phase III trials of sepsis (rh-APC, AT and rh-TFPI), and those commercially available and frequently given to critically ill patients (heparin and danaparoid). The same search strategy was used in Embase. A Prisma flow diagram of the applied search strategy and selection process is summarized in Figure 2.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts of identified manuscripts were reviewed on:

-

Population (that is, animal models of lung injury or patients with ALI) and the related settings (pneumonia, sepsis or VILI)

-

Intervention (that is, local anticoagulation)

-

Outcome (that is, lung injury and inflammation, pulmonary coagulation, systemic coagulation and bleeding)

In case of uncertainty, the complete manuscript was obtained and evaluated.

Data extraction

Manuscripts were critically appraised along two research questions:

-

Do nebulized anticoagulants affect pulmonary coagulation, parameters of lung injury, and/or outcome?

-

Do nebulized anticoagulants affect systemic coagulation and, as such, cause bleedings?

Results

Preclinical studies of local anticoagulation

The search of preclinical studies of pulmonary anticoagulation yielded 10 preclinical studies of nebulized and one with intratracheal anticoagulants for lung injury with a large diversity in outcome measures (Table 1). Four preclinical studies tested nebulized rh-APC [32–35], four studies compared rh-APC, plasma-derived human AT, heparin and danaparoid [36–39], one study tested heparin [40], one study compared nebulized heparin with systemic infusion of heparin [41], and one study compared nebulized heparin with systemic infusion of heparin and lisofylline (LSF) [42]. The search did not yield any preclinical study that investigated the effects of nebulized rh-TFPI.

Recombinant human-activated protein C

Although in none of the preclinical studies pulmonary levels of rh-APC were measured, nebulization of rh-APC was found to attenuate activation of pulmonary coagulation [34, 36, 37], and to stimulate pulmonary fibrinolysis [36]. Nebulization of rh-APC inconsistently reduced pulmonary inflammation [34–36]. Furthermore, nebulization of rh-APC was found to improve oxygenation [32, 34, 35], and to reduce histolopathological derangements [32, 34, 35]. While nebulization of rh-APC improved aerated lung volume, it had no effect on extravascular lung water (EVLW) [33]. Nebulization of rh-APC has neither been associated with systemic coagulation [33] nor with signs of systemic bleeding [36]. Dosages and timing of rh-APC varied amongst studies: from five times 48 μg/kg [33] up to 200 mg/kg as a single dose [35].

Plasma-derived human antithrombin

Nebulization of plasma-derived AT was found to increase pulmonary levels of AT [36, 37], to attenuate activation of pulmonary coagulation [36, 37] and to stimulate pulmonary fibrinolysis [36]. Alike with rh-APC, nebulized plasma-derived AT inconsistently reduced pulmonary inflammation [36, 38]. Furthermore, nebulization of plasma-derived AT was found to reduce histopathological derangements and bacterial outgrowth in models of infectious lung injury [36]. Nebulization of plasma-derived AT has not been associated with an affect on systemic coagulation [36, 37]. Dosages of plasma-derived AT varied amongst studies: from 10 IU/kg [38] to as high as 500 IU/kg [36, 37].

Heparin

Nebulization of heparin and intratracheal-installed heparin were found to attenuate pulmonary coagulopathy [36, 37, 40]. Nebulization of heparin, as expected, was not found to affect fibrinolysis [36, 37, 40]. Intratracheal-installed heparin reduced pulmonary inflammation and endothelial permeability. In addition intratracheal-installed heparin improved survival, reduced bacterial outgrowth and bacterial adherence to lung epithelium [40]. Nebulization of heparin did not reduce pulmonary inflammation [37]. Furthermore, nebulization of heparin did affect systemic coagulation [37]. The dosages of heparin varied between an estimated 333 IU/kg [38, 39, 41, 42] and 1000 IU/kg [36, 37].

Danaparoid

Nebulization of danaparoid was also found to attenuate pulmonary coagulopathy but not fibrinolysis [36, 37]. Danaparoid reduced local coagulation, but not inflammation [37]. Danaparoid was found to have an effect on systemic coagulation [36, 37]. A dose of 250 E/kg was used in both studies.

Combined therapies

Combined nebulization of AT or systemic infusion of AT with nebulization of heparin was found to reduce wet-to-dry lung weight ratios and airway obstructions, and to improve lung function [38, 39]. Combined nebulization of heparin and systemic lysofylline was found to reduce need for mechanical ventilation, to decrease pulmonary shunt fraction, but not to reduce wet-to-dry lung weight ratios [42]. Combined nebulization of heparin and AT was not found to affect clotting times [38, 39].

Clinical trials of nebulized anticoagulants

The search did not yield any clinical trial that investigated the effects of nebulization of rh-APC, plasma-derived human AT or rh-TFPI; three trials tested the nebulization of heparin (Table 2).

Heparin

In a phase I trial of patients with ALI, heparin was nebulized at different dosages, namely 50,000 U/day, 100,000 U/day, 200,000 U/day or 400,000 U/day for two days. An Aeroneb Pro (Aerogen, Galway, Ireland) vibrating mesh nebulizer was used in this study. Sixteen patients were enrolled with a mean age of 58 years. Patients were ventilated in a pressure-support mode of ventilation and peak airway pressures were maintained below 35 cm H2O. Nebulization of heparin partly prevented activation of coagulation, evidenced by a reduction of thrombin-antithrombin complexes and fibrin degradation products in the broncheoalveolar lavage fluid, but lung function remained unchanged. With higher dosages, nebulization of heparin was found to be associated with an increase of systemic activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) [43, 44], without causing systemic bleedings.

In a single-center, retrospective case-control study of 30 patients with smoke inhalation-associated ALI, cases were compared with historical controls. All patients were ventilated with volume-cycled ventilation at a tidal volume of 5 to 8 ml/kg. The peak airway pressures were maintained below 40 cmH2O. The dose of nebulized heparin used was 10,000 U every four hours for seven consecutive days. Nebulization of heparin combined with N-acetylcysteine and albuterol sulfate was associated with an improved survival and improved lung injury scores (LIS) [45]. No data on pulmonary coagulation or inflammation and nebulizer used were reported.

In a randomized controlled trial of 50 patients who were expected to require mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours' treatment with 25,000 U of heparin for six times a day, with a maximum of 14 days, was compared to placebo [15]. An Aeroneb Pro vibrating mesh nebulizer was used in this study. Of note, pulmonary levels of coagulation and inflammation were not affected. No difference in bleeding events was observed between groups, even in patients with co-administrated systemic heparin, but APTT levels were higher in the intervention group. No effect on mortality was seen, but treatment with heparin was associated with fewer days of mechanical ventilation (MV) and a trend for a higher PaO2/FiO2 (P/F) ratio.

Discussion

Ten years ago, to many in the pulmonary or critical care community the idea that anticoagulants could be a beneficial therapy in ALI may have been surprising and the approach unfamiliar [46]. Nowadays, several preclinical and clinical trials have been conducted with anticoagulants in the setting of experimental lung injury in animals or ALI in humans. The clinical evidence for pulmonary anticoagulant therapy is severely limited, since only one randomized controlled trial has been performed. The identified preclinical studies all showed clear evidence for attenuating effects of nebulized anticoagulants on local coagulation, a phenomenon that has been associated with morbidity and mortality of ALI. Given the extensive crosstalk between inflammation and coagulation [47], the observed diminishing effects on local coagulation may be countable for dampened pulmonary inflammation with nebulization of anticoagulants.

It should be noted that while rh-APC and rh-TFPI were infused in a continuous fashion in clinical trials of sepsis [17, 23, 30, 31, 48, 49], in the reviewed preclinical studies these anticoagulants were nebulized intermittently. Although half-life of rh-APC in plasma is short [50], rh-APC could be detected in mice bronchoalveolar lavage fluid up to 24 hours after inhalation [51]. It is uncertain whether continuous nebulization would improve the pulmonary effects of rh-APC, but considering longer bioavailability and intermittent dosing, local administration may affect both efficacy and costs.

Nebulization of rh-APC or plasma-derived human AT did not affect systemic coagulation, suggesting local administration of these agents to be safe and, as such, to have a potential benefit over systemic administration. Nebulization of heparin or danaparoid, however, did affect systemic parameters of coagulation. These agents seem to have the potential to leak from the pulmonary compartment into the circulation [36, 37]. This may not come as a surprise, since both heparin and danaparoid are relatively small molecules (8 and 5.5 kDa respectively), much lower than APC and AT (56 and 58 kDa respectively). Of note, in a phase I trial, nebulization of heparin in a high dosages lengthened clotting time only after > 24 hours [43], suggesting that heparin may be stored and metabolized in pulmonary endothelial cells, initially limiting heparin from reaching the systemic circulation. Notably, the results from the clinical trials of nebulization of heparin showed no increase on systemic bleedings.

Five major variables influence local drug delivery in the lung during mechanical ventilation, that is, the aerosol generator, aerosol particle size, conditions in the ventilatory circuit, artificial airway and ventilator parameters [52]. Unfortunately, most of these variables were insufficiently addressed in the retrieved studies. In addition, different types and brands of nebulizers were used, including jet [35, 41], ultrasonic [33] and vibrating mesh nebulizers [34, 36, 37]. Some studies did not report which nebulizer was used [38, 39, 42]. No studies mention the particle size delivered by the used nebulizer and probable losses of study drug, which would have been of interest, since it is one of the determinants of drug delivery to the lungs [52]. In addition, maldistribution of nebulized drugs to areas of better ventilation away from areas of collapse and consolidation is a concern of nebulized agents. After nebulization, uptake through the bronchial mucosa and distribution by a rich network of submucosal capillaries to other areas of the lung, could lead to adequate concentrations at various sites in the lung, as seen with inhaled antibiotics [53]. Another potential risk is that with higher local concentrations of anticoagulants in the lung, systemic measures of anticoagulation may not measure local bleeding risk. These aspects need further attention in future studies.

A potential harm from local anticoagulant therapies lies in the fact that part of the procoagulant response may be needed for healing. Notably, coagulation and the formation of fibrin are natural responses to injury. The coagulation system may play a role in containing pathogens to the side of infection [54]. In a model of Pseudomonas pneumonia, interfering with the initial procoagulant response showed to be a potentially dangerous strategy, since it was associated with increased bacteremia [55, 56]. In the studies identified by our search, no increased spread of bacteria was observed, though. On the other hand, anticoagulants may also have beneficial antimicrobial effects. Indeed, local heparin has been shown to have an anti-adherence effect, making it, for Legionella pneumophila, unable to adhere to airway epithelial cells in the alveolar space [40]. Also, AT has been shown to limit bacterial outgrowth of Streptococcus pneumoniae in a rat model of pneumonia with this pathogen [36]. Thus, anticoagulants could also act as an adjuvant to conventional antimicrobial therapy in patients who are mechanically ventilated.

Our search identified only three trials of local anticoagulants in patients [15, 43, 45]. The trial of patients who needed prolonged mechanical ventilation knows several potential weaknesses. The population was very heterogeneous, since it included unselected patients requiring mechanical ventilation beyond 48 hours, independent of the reason. Furthermore, a large proportion of patients received systemic heparin (24 versus 32%, in heparin-treated and control patients respectively). Finally, it should be mentioned that this trial was performed in a single ICU.

Investigations in animals and patients with burns and smoke inhalation and burns are a distinct category, since this insult is characterized by massive airway obstructive casts [38], resulting in atelectasis, air trapping, alveolar hyperinflation and barotraumas, and maybe even pneumonia [39, 57, 58]. The effects of nebulized anticoagulants on cast formation may not be comparable to the anticoagulant effects of these agents in ALI by another cause. One major weakness of the clinical trial that showed beneficial effects of nebulized heparin in these patients is that historic controls were used [45]. Furthermore, side-effects were not reported.

Due to the marked differences in study design and patient characteristics, the cumulative summary of these data should be interpreted with caution. But this preliminary analysis, despite a number of caveats, suggests further studies to be undertaken. We are in need of more animal studies and clinical trials that address the promising concept of administration of anticoagulants to the lungs. We favor mechanistic studies before randomized controlled trials for several reasons. First, dosages were arbitrarily chosen in most preclinical studies. Second, assessment of distribution of inhaled anticoagulants in the lungs and its final (plasma) concentrations have to be better addressed. While larger agents may have limited access to the lower airways, smaller agents may leak more easily into the systemic circulation. Third, animal models of pneumonia should mimic as much as possible the clinical scenario and as such, should include, for instance, the use of antibiotics.

Conclusions

Preclinical studies in models of lung injury show nebulization of anticoagulants to reduce pulmonary coagulopathy and inflammation. Neither nebulized APC nor nebulized AT affects systemic coagulation, whereas heparin and danaparoid do affect systemic coagulation. Initial clinical trials of nebulized heparin show beneficial effects in ALI.

Key messages

-

Nebulization of anticoagulants attenuates pulmonary coagulopathy and pulmonary inflammation

-

Neither nebulized APC nor nebulized AT affect systemic coagulation, whereas heparin and danaparoid do affect systemic coagulation

-

Nebulization of heparin improves survival in patients with smoke inhalation-associated ALI

-

Nebulization of heparin reduces the days of mechanical ventilation in patients with prolonged need for mechanical ventilation

Abbreviations

- ALI:

-

acute lung injury

- APC:

-

activated protein C

- APTT:

-

activated partial thromboplastin time

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AT:

-

antithrombin

- EVLW:

-

extravascular lung water

- i.t.:

-

intratracheal

- i.v.:

-

intravenous

- LIS:

-

lung injury score

- LSF:

-

lisofylline

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

- MV:

-

mechanical ventilation

- MeSH:

-

medical subject headings

- P/F:

-

PaO2/FiO2

- rh:

-

recombinant human

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- TATc:

-

thrombin-antithrombin complex

- TF:

-

tissue factor

- TFPI:

-

tissue factor pathway inhibitor

- VCAM-1:

-

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

- VILI:

-

ventilator-induced lung injury.

References

Gunther A, Mosavi P, Heinemann S, Ruppert C, Muth H, Markart P, Grimminger F, Walmrath D, Temmesfeld-Wollbruck B, Seeger W: Alveolar fibrin formation caused by enhanced procoagulant and depressed fibrinolytic capacities in severe pneumonia. Comparison with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161: 454-462.

Ware LB, Matthay MA: The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000, 342: 1334-1349. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806

Bastarache JA, Ware LB, Bernard GR: The role of the coagulation cascade in the continuum of sepsis and acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 27: 365-376. 10.1055/s-2006-948290

Schultz MJ, Haitsma JJ, Zhang H, Slutsky AS: Pulmonary coagulopathy as a new target in therapeutic studies of acute lung injury or pneumonia - a review. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 871-877.

Levi M, Schultz MJ, Rijneveld AW, Van Der Poll T: Bronchoalveolar coagulation and fibrinolysis in endotoxemia and pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: S238-S242. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057849.53689.65

Afshari A, Wetterslev J, Brok J, Moller AM: Antithrombin III for critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008, CD005370.

Ware LB, Fang X, Matthay MA: Protein C and thrombomodulin in human acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003, 285: L514-L521.

Ware LB, Matthay MA, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Januzzi JL, Eisner MD: Pathogenetic and prognostic significance of altered coagulation and fibrinolysis in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 1821-1828. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000221922.08878.49

Russell JA: Genetics of coagulation factors in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: S243-S247. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057870.61079.3E

Levi M, ten CH: Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med 1999, 341: 586-592. 10.1056/NEJM199908193410807

Fourrier F, Chopin C, Goudemand J, Hendrycx S, Caron C, Rime A, Marey A, Lestavel P: Septic shock, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Compared patterns of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S deficiencies. Chest 1992, 101: 816-823. 10.1378/chest.101.3.816

Ware LB: Pathophysiology of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 27: 337-349. 10.1055/s-2006-948288

Laterre PF, Wittebole X, Dhainaut JF: Anticoagulant therapy in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: S329-S336. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057912.71499.A5

Gropper MA, Wiener-Kronish J: The epithelium in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care 2008, 14: 11-15. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f417a0

Dixon B, Schultz MJ, Smith R, Fink JB, Santamaria JD, Campbell DJ: Nebulized heparin is associated with fewer days of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 2010, 14: R180. 10.1186/cc9286

Scotton CJ, Krupiczojc MA, Konigshoff M, Mercer PF, Lee YC, Kaminski N, Morser J, Post JM, Maher TM, Nicholson AG, Moffat JD, Laurent GJ, Derian CK, Eickelberg O, Chambers RC: Increased local expression of coagulation factor × contributes to the fibrotic response in human and murine lung injury. J Clin Invest 2009, 119: 2550-2563.

Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, LaRosa SP, Dhainaut JF, Lopez-Rodriguez A, Steingrub JS, Garber GE, Helterbrand JD, Ely EW, Fisher CJ: Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2001, 344: 699-709. 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001

Dhainaut JF, Laterre PF, Janes JM, Bernard GR, Artigas A, Bakker J, Riess H, Basson BR, Charpentier J, Utterback BG, Vincent JL: Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in the treatment of severe sepsis patients with multiple-organ dysfunction: data from the PROWESS trial. Intensive Care Med 2003, 29: 894-903.

Laterre PF, Garber G, Levy H, Wunderink R, Kinasewitz GT, Sollet JP, Maki DG, Bates B, Yan SC, Dhainaut JF: Severe community-acquired pneumonia as a cause of severe sepsis: data from the PROWESS study. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 952-961. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000162381.24074.D7

Liu KD, Levitt J, Zhuo H, Kallet RH, Brady S, Steingrub J, Tidswell M, Siegel MD, Soto G, Peterson MW, Chesnutt MS, Phillips C, Weinacker A, Thompson BT, Eisner MD, Matthay MA: Randomized clinical trial of activated protein C for the treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008, 178: 618-623. 10.1164/rccm.200803-419OC

Angus DC: Drotrecogin alfa (activated) ... a sad final fizzle to a roller-coaster party. Crit Care 2012, 16: 107. 10.1186/cc11152

Warren BL, Eid A, Singer P, Pillay SS, Carl P, Novak I, Chalupa P, Atherstone A, Penzes I, Kubler A, Knaub S, Keinecke HO, Heinrichs H, Schindel F, Juers M, Bone RC, Opal SM: Caring for the critically ill patient. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001, 286: 1869-1878. 10.1001/jama.286.15.1869

Abraham E, Reinhart K, Opal S, Demeyer I, Doig C, Rodriguez AL, Beale R, Svoboda P, Laterre PF, Simon S, Light B, Spapen H, Stone J, Seibert A, Peckelsen C, De Deyne C, Postier R, Pettila V, Artigas A, Percell SR, Shu V, Zwingelstein C, Tobias J, Poole L, Stolzenbach JC, Creasey AA: Efficacy and safety of tifacogin (recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor) in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003, 290: 238-247. 10.1001/jama.290.2.238

Eisele B, Lamy M, Thijs LG, Keinecke HO, Schuster HP, Matthias FR, Fourrier F, Heinrichs H, Delvos U: Antithrombin III in patients with severe sepsis. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicenter trial plus a meta-analysis on all randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials with antithrombin III in severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med 1998, 24: 663-672. 10.1007/s001340050642

Laterre PF, Opal SM, Abraham E, LaRosa SP, Creasey AA, Xie F, Poole L, Wunderink RG: A clinical evaluation committee assessment of recombinant human tissue factor pathway inhibitor (tifacogin) in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care 2009, 13: R36. 10.1186/cc7747

Wunderink RG, Laterre PF, Francois B, Perrotin D, Artigas A, Vidal LO, Lobo SM, San JJ, Hwang SC, Dugernier T, Larosa S, Wittebole X, Dhainaut JF, Doig C, Mendelson MH, Zwingelstein C, Su G, Opal S: Recombinant Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor in Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Randomized Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011.

Cornet AD, Smit EG, Beishuizen A, Groeneveld AB: The role of heparin and allied compounds in the treatment of sepsis. Thromb Haemost 2007, 98: 579-586.

Jaimes F, De La Rosa G, Morales C, Fortich F, Arango C, Aguirre D, Munoz A: Unfractioned heparin for treatment of sepsis: A randomized clinical trial (The HETRASE Study). Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 1185-1196. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c06bc

Honeybourne D: Antibiotic penetration in the respiratory tract and implications for the selection of antimicrobial therapy. Curr Opin Pulm Med 1997, 3: 170-174. 10.1097/00063198-199703000-00014

Vincent JL, Bernard GR, Beale R, Doig C, Putensen C, Dhainaut JF, Artigas A, Fumagalli R, Macias W, Wright T, Wong K, Sundin DP, Turlo MA, Janes J: Drotrecogin alfa (activated) treatment in severe sepsis from the global open-label trial ENHANCE: further evidence for survival and safety and implications for early treatment. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 2266-2277. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000181729.46010.83

Abraham E, Laterre PF, Garg R, Levy H, Talwar D, Trzaskoma BL, Francois B, Guy JS, Bruckmann M, Rea-Neto A, Rossaint R, Perrotin D, Sablotzki A, Arkins N, Utterback BG, Macias WL: Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. N Engl J Med 2005, 353: 1332-1341. 10.1056/NEJMoa050935

Maniatis NA, Letsiou E, Orfanos SE, Kardara M, Dimopoulou I, Nakos G, Lekka ME, Roussos C, Armaganidis A, Kotanidou A: Inhaled activated protein C protects mice from ventilator-induced lung injury. Crit Care 2010, 14: R70. 10.1186/cc8976

Waerhaug K, Kuzkov VV, Kuklin VN, Mortensen R, Nordhus KC, Kirov MY, Bjertnaes LJ: Inhaled aerosolised recombinant human activated protein C ameliorates endotoxin-induced lung injury in anaesthetised sheep. Crit Care 2009, 13: R51. 10.1186/cc7777

Slofstra SH, Groot AP, Maris NA, Reitsma PH, Cate HT, Spek CA: Inhalation of activated protein C inhibits endotoxin-induced pulmonary inflammation in mice independent of neutrophil recruitment. Br J Pharmacol 2006, 149: 740-746. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706915

Kotanidou A, Loutrari H, Papadomichelakis E, Glynos C, Magkou C, Armaganidis A, Papapetropoulos A, Roussos C, Orfanos SE: Inhaled activated protein C attenuates lung injury induced by aerosolized endotoxin in mice. Vascul Pharmacol 2006, 45: 134-140. 10.1016/j.vph.2006.06.016

Hofstra JJ, Cornet AD, de Rooy BF, Vlaar AP, Van Der Poll T, Levi M, Zaat SA, Schultz MJ: Nebulized antithrombin limits bacterial outgrowth and lung injury in Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia in rats. Crit Care 2009, 13: R145. 10.1186/cc8040

Hofstra JJ, Vlaar AP, Cornet AD, Dixon B, Roelofs JJ, Choi G, Van Der Poll T, Levi M, Schultz MJ: Nebulized anticoagulants limit pulmonary coagulopathy, but not inflammation, in a model of experimental lung injury. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2010, 23: 105-111. 10.1089/jamp.2009.0779

Enkhbaatar P, Cox RA, Traber LD, Westphal M, Aimalohi E, Morita N, Prough DS, Herndon DN, Traber DL: Aerosolized anticoagulants ameliorate acute lung injury in sheep after exposure to burn and smoke inhalation. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 2805-10. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000291647.18329.83

Enkhbaatar P, Esechie A, Wang J, Cox RA, Nakano Y, Hamahata A, Lange M, Traber LD, Prough DS, Herndon DN, Traber DL: Combined anticoagulants ameliorate acute lung injury in sheep after burn and smoke inhalation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008, 114: 321-329. 10.1042/CS20070254

Ader F, Le BR, Fackeure R, Raze D, Menozzi FD, Viget N, Faure K, Kipnis E, Guery B, Jarraud S, Etienne J, Chidiac C: In vivo effect of adhesion inhibitor heparin on Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis in a murine pneumonia model. Intensive Care Med 2008, 34: 1511-1519. 10.1007/s00134-008-1063-2

Murakami K, McGuire R, Cox RA, Jodoin JM, Bjertnaes LJ, Katahira J, Traber LD, Schmalstieg FC, Hawkins HK, Herndon DN, Traber DL: Heparin nebulization attenuates acute lung injury in sepsis following smoke inhalation in sheep. Shock 2002, 18: 236-241. 10.1097/00024382-200209000-00006

Tasaki O, Mozingo DW, Dubick MA, Goodwin CW, Yantis LD, Pruitt BA Jr: Effects of heparin and lisofylline on pulmonary function after smoke inhalation injury in an ovine model. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 637-643. 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00024

Dixon B, Santamaria JD, Campbell DJ: A phase 1 trial of nebulised heparin in acute lung injury. Crit Care 2008, 12: R64. 10.1186/cc6894

Dixon B, Schultz MJ, Hofstra JJ, Campbell DJ, Santamaria JD: Nebulized heparin reduces levels of pulmonary coagulation activation in acute lung injury. Crit Care 2010, 14: 445. 10.1186/cc9269

Miller AC, Rivero A, Ziad S, Smith DJ, Elamin EM: Influence of nebulized unfractionated heparin and N-acetylcysteine in acute lung injury after smoke inhalation injury. J Burn Care Res 2009, 30: 249-256. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318198a268

Idell S: Anticoagulants for acute respiratory distress syndrome: can they work? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164: 517-520.

Schultz MJ, Dixon B: A breathtaking and bloodcurdling story of coagulation and inflammation in acute lung injury. J Thromb Haemost 2009, 7: 2050-2052. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03639.x

Shorr AF, Janes JM, Artigas A, Tenhunen J, Wyncoll DL, Mercier E, Francois B, Vincent JL, Vangerow B, Heiselman D, Leishman AG, Zhu YE, Reinhart K: Randomized trial evaluating serial protein C levels in severe sepsis patients treated with variable doses of drotrecogin alfa (activated). Crit Care 2010, 14: R229. 10.1186/cc9382

Abraham E, Reinhart K, Svoboda P, Seibert A, Olthoff D, Dal NA, Postier R, Hempelmann G, Butler T, Martin E, Zwingelstein C, Percell S, Shu V, Leighton A, Creasey AA: Assessment of the safety of recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor in patients with severe sepsis: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind, dose escalation study. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 2081-2089. 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00007

Van Der Poll T, Levi M, Nick JA, Abraham E: Activated protein C inhibits local coagulation after intrapulmonary delivery of endotoxin in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171: 1125-1128. 10.1164/rccm.200411-1483OC

Yuda H, Adachi Y, Taguchi O, Gabazza EC, Hataji O, Fujimoto H, Tamaki S, Nishikubo K, Fukudome K, D'Alessandro-Gabazza CN, Maruyama J, Izumizaki M, Iwase M, Homma I, Inoue R, Kamada H, Hayashi T, Kasper M, Lambrecht BN, Barnes PJ, Suzuki K: Activated protein C inhibits bronchial hyperresponsiveness and Th2 cytokine expression in mice. Blood 2004, 103: 2196-2204. 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1980

Dhand R: Aerosol delivery during mechanical ventilation: from basic techniques to new devices. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2008, 21: 45-60. 10.1089/jamp.2007.0663

McCullagh A, Rosenthal M, Wanner A, Hurtado A, Padley S, Bush A: The bronchial circulation - worth a closer look: a review of the relationship between the bronchial vasculature and airway inflammation. Pediatr Pulmonol 2010, 45: 1-13.

Lahteenmaki K, Kuusela P, Korhonen TK: Bacterial plasminogen activators and receptors. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2001, 25: 531-552.

Robriquet L, Collet F, Tournoys A, Prangere T, Neviere R, Fourrier F, Guery BP: Intravenous administration of activated protein C in Pseudomonas-induced lung injury: impact on lung fluid balance and the inflammatory response. Respir Res 2006, 7: 41. 10.1186/1465-9921-7-41

Kipnis E, Guery BP, Tournoys A, Leroy X, Robriquet L, Fialdes P, Neviere R, Fourrier F: Massive alveolar thrombin activation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury. Shock 2004, 21: 444-451. 10.1097/00024382-200405000-00008

Pruitt BA, Cioffi WG: Diagnosis and treatment of smoke inhalation. J Intensive Care Med 1995, 10: 117-127.

Enkhbaatar P, Murakami K, Cox R, Westphal M, Morita N, Brantley K, Burke A, Hawkins H, Schmalstieg F, Traber L, Herndon D, Traber D: Aerosolized tissue plasminogen inhibitor improves pulmonary function in sheep with burn and smoke inhalation. Shock 2004, 22: 70-75. 10.1097/01.shk.0000129201.38588.85

Tuinman PR, Schultz MJ, Juffermans NP: Coagulopathy as a therapeutic target for TRALI: rationale and possible sites of action. Curr Pharm Des 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PRT was intimately involved in data gathering, interpretation of the results as well as manuscript preparation. He has read the final version of the manuscript and agrees with all reported findings and interpretations. BD was intimately involved in interpretation of the results and manuscript. He has read the final version of the manuscript and agrees with all reported findings and interpretations. ML and NPJ are members of an expert panel dealing with coagulation and coagulation disorders in critically ill patients. They were instrumental in study hypothesis. They were intimately involved with interpretation of the results and manuscript. They have read the final version of the manuscript and agree with all reported findings. MJS was instrumental in study design, data analysis and preparing the manuscript. He has read the final version of the manuscript and agrees with all reported findings and interpretations.

All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tuinman, P.R., Dixon, B., Levi, M. et al. Nebulized anticoagulants for acute lung injury - a systematic review of preclinical and clinical investigations. Crit Care 16, R70 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11325

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11325