Abstract

Introduction

A strong biologic rationale exists for targeting markers of endothelial cell (EC) activation as clinically informative biomarkers to improve diagnosis, prognostic evaluation or risk-stratification of patients with sepsis.

Methods

The objective was to review the literature on the use of markers of EC activation as prognostic biomarkers in sepsis. MEDLINE was searched for publications using the keyword 'sepsis' and any of the identified endothelial-derived biomarkers in any searchable field. All clinical studies evaluating markers reflecting activation of ECs were included. Studies evaluating other exogenous mediators of EC dysfunction and studies of patients with malaria and febrile neutropenia were excluded.

Results

Sixty-one studies were identified that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Overall, published studies report positive correlations between multiple EC-derived molecules and the diagnosis of sepsis, supporting the critical role of EC activation in sepsis. Multiple studies also reported positive associations for mortality and severity of illness, although these results were less consistent than for the presence of sepsis. Very few studies, however, reported thresholds or receiver operating characteristics that would establish these molecules as clinically-relevant biomarkers in sepsis.

Conclusions

Multiple endothelial-derived molecules are positively correlated with the presence of sepsis in humans, and variably correlated to other clinically-important outcomes. The clinical utility of these biomarkers is limited by a lack of assay standardization, unknown receiver operating characteristics and lack of validation. Additional large-scale prospective clinical trials will be required to determine the clinical utility of biomarkers of endothelial activation in the management of patients with sepsis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is a complex syndrome that results from a host's response to invasive infection [1, 2], and severe sepsis with organ dysfunction and septic shock are leading causes of death in critically ill patients [3]. A tool that would predict prognosis or allow risk-stratification of patients is needed to inform healthcare providers, families and decision makers, and facilitate the study and implementation of evolving therapeutic interventions.

A biomarker is defined as "...a characteristic that is objectively measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacologic responses to therapeutic intervention" [4]. Despite the proposal of over 100 distinct biological molecules as biomarkers for sepsis, no useful single biomarker, or combination thereof, has yet been identified [5].

A hallmark of sepsis is a change in microvascular function. Widespread endothelial damage and apoptosis appears to be directly involved (see Figure 1), with numerous associations observed between sepsis and endothelial cell (EC) activation [6–10]. Consequently, there is a strong biologic rationale for targeting markers of endothelial activation as biomarkers of sepsis. A large number of EC-active molecules have been investigated as potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis, triage and prognostication of sepsis. These include regulators of endothelial activation, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endocan and the angiopoeitin pathway (Ang-1/2), adhesion molecules such as s-ICAM-1, sVCAM-1, and sE-selectin-1), mediators of permeability and vasomotor tone (s-Flt and endothelin-1); and mediators of coagulation (vWF, ADAMTS13).

Endothelial activation induces increased production of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin. E-selectin induces leukocyte rolling, and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 bind leukocyte function antigen 1 (LFA1) and very late antigen 4 (VLA4), respectively, to induce firm leukocyte adhesion. Activation is partially mediated by VEGF binding to VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR1, also known as Flt-1) and VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2). Soluble Flt-1 binds VEGF competitively to render an anti-inflammatory response in the setting of sepsis. Ang-1 is constitutively secreted by pericytes and smooth muscle cells. Upon activation, Ang-2 is rapidly released by Weibel-Palade bodies, competitively interfering with Ang-1/Tie2 signaling and thereby increasing expression of adhesion molecules.

Given the potential for, and growing interest in, EC-derived molecules as biomarkers in sepsis, we conducted a systematic review of the current published literature of biomarkers to determine their performance in predicting the severity of sepsis and clinical outcomes. This systematic review will serve as an update and supplement to other recent reviews in the literature [5, 11–14], given the rapidly evolving nature of the field.

Materials and methods

Data sources

We systematically and inclusively identified all studies evaluating markers of endothelial activation, (including angiopoietins and sTie2R, sVEGF and sFlt-1, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, sE-selectin, endothelin-1, endocan, VWF and ADAMTS13) in sepsis. We electronically searched MEDLINE (1950 to Week 2, September 2011) and EMBASE (1980 to Week 37, 2011) databases for all pertinent English language studies. (Please see Additional file 1, Search Strategy).

Study selection methods

Study selection was performed independently by three reviewers (KX, SM, JMS), with disagreements resolved through arbitration by a fourth reviewer (WCL). A study was included if it (1) studied adult patients with sepsis or the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), or studied patients at risk for sepsis or SIRS, and (2) evaluated a clinical endpoint (the development of sepsis, sepsis severity, development of organ dysfunction or mortality). Studies of patients less than 18 years of age, patients with febrile neutropenia, patients with malaria, interventional clinical trials studying a specific intervention or medication and case reports were excluded.

Study data extraction and analysis

For each of the selected studies, we extracted the biomarker(s) evaluated, study size and patient population, and details of the primary and secondary outcomes. Outcomes of interest for each biomarker were tabulated and compared across studies where appropriate. Study design, standardization of sepsis definition and other methodological data were extracted and each study was subject to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system for assessing the quality of evidence [15]. Due to the anticipated broad study heterogeneity and disparate study outcomes, we did not attempt to numerically combine or perform a meta-analysis of study results.

Results

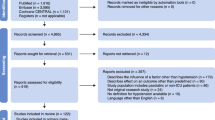

Our search identified 1,243 unique articles (see Figure 2). A total of 84 studies met our predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, of which a further 23 studies were excluded after retrieval of full-text publication for the following reasons: 14 studies did not report a clinical outcome [16–29], 4 studies did not include a relevant patient population [30–32], 3 studies were interventional trials [33–35], and 2 studies were not in English and the English abstracts provided insufficient information to allow adjudication of study inclusion [36, 37]. The remaining 61 studies were included in our review.

All studies were observational designs, including secondary analyses of data collected during prospective clinical trials. Most studies used standard consensus definitions of sepsis. Interpretation of the magnitude of effect or association between biomarkers and sepsis or clinical outcomes was limited by a lack of standardization in individual biomarker assays, an absence of identified or validated thresholds or cut-points in individual biomarker levels, and a lack of reported odds ratios or relative risk. Several studies identified positive associations between biomarker levels and severity of sepsis (for example, sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock), but given the aforementioned limitations and heterogeneity across studies in this association, we did not deem this to be sufficient evidence of a dose-response association to upgrade the quality level of these studies given the aforementioned limitations. Consequently, all studies were assigned a GRADE level of 'low quality' with respect to the association between individual biomarker levels and sepsis [15].

The Angiopoietin system

We identified 11 studies investigating angiopoietin 2 (Ang-2) as a biomarker in human sepsis (see Table 1- Studies Evaluating Angiopoietin-2). All but one were prospective observational studies [38–44], with one secondary analysis of a previously conducted cohort study [45].

Association with sepsis

Seven studies evaluated the association between Ang-2 levels and sepsis, reporting higher levels of Ang-2 in patients with sepsis compared to patients without sepsis in the ward setting [43, 44], the ICU [38, 40, 42, 45], and patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS) [45]. Ang-2 levels were also higher in sepsis than in either patients with sterile SIRS [40] or healthy controls [41]. Kumpers et al. also reported that Ang-2 concentrations were elevated in all ICU patients (irrespective of sepsis status) compared to healthy controls [42]. One study found that patients who did not have SIRS/sepsis on admission but subsequently developed SIRS/sepsis, had significant increases in Ang-2 over time [40].

There were inconsistent reports of the association between Ang-2 and the severity of sepsis (as defined by sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock), with one positive study [44] and four studies that failed to observe a consistent correlation [38, 39, 41, 42]. Higher levels of Ang-2 were also reported in patients with severe sepsis compared to septic ICU patients without organ dysfunction [38, 43, 44], non-septic hospitalized controls [43, 44], and ICU patients without SIRS [38].

None of the studies identified a cut point or threshold of circulating Ang-2 that allowed differentiation of patients with sepsis and without sepsis, or stratification of patients with respect to sepsis severity based on baseline or serial serum Ang-2 concentrations.

Association with clinical outcome

Three studies [39, 40, 42] observed associations between circulating Ang-2 levels and severity of illness as defined by Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) [46] or Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (SOFA) [47], and five studies reported a relationship between increasing Ang-2 levels and increasing mortality [39–42, 48]. Kumpers et al. found that circulating Ang-2 levels were independently associated with 30-day survival after adjustment for APACHE II score, SOFA score and serum lactate levels [42]. Kranidioti et al. found that Ang-2 concentrations were associated with sepsis-related mortality at baseline and every day for the first seven days in ICU, and Ang-2 levels greater than 9.7 ng/mL were associated with a three-fold increased risk of sepsis-related mortality [41]. Siner et al. found higher Ang-2 levels were associated with hospital motality, and the patient cohort could be stratified for hospital mortality by admission Ang-2 levels [39]. Ricciuto et al. observed that serial measurements of Ang-2 were associated with 28-day mortality and multiple organ dysfunction (MOD) score [48].

One study found Ang-2 was independently associated with the severity of lung injury as measured by pulmonary leak, and was predictive for the development of ARDS [45]. A second study found an inverse correlation between Ang-2 and PaO2/FiO2 ratio [49]. Page et al. found that the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio was significantly increased in patients with invasive streptococcal infection who developed toxic shock syndrome, compared to those with uncomplicated infection [50].

The leukocyte adhesion pathway

We identified 19 studies investigating sICAM-1 as a sepsis biomarker (see Table 2-Studies evaluating sICAM), 12 studies for sVCAM-1 (see Table 3-Studies Evaluating sVCAM-1), 23 studies for sE-selectin-1 (Table 4-Studies Evaluating sE-selectin-1), and 2 studies for endocan (see Table 5-Studies Evaluating Endocan). All were prospective studies or secondary analyses of prospective studies. These studies focused on emergency room patients with suspected infections or shock [51, 52], and critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units, including medical and surgical patients [51, 53–76], patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) [73], trauma [62, 63, 66, 67, 75], and post-cardiopulmonary resuscitation [74].

Soluble ICAM-1

Association with sepsis

All studies comparing sICAM-1 in septic patients and healthy controls reported higher levels in septic patients [54, 55, 58, 59, 65, 66, 68]. sICAM-1 was also found to be significantly higher in sepsis than in patients with trauma [61, 62, 66, 67], postoperative patients [55], patients with other forms of shock [52], and non-septic ICU patients [59, 66, 68]. One study reported that sICAM-1 levels were similar in septic patients and ICU patients without sepsis [65]. Two studies explicitly compared sICAM-1 in patients with sepsis and SIRS [53, 68], but only one found higher sICAM-1 in sepsis [53]. Several studies observed that baseline sICAM-1 levels were similar in non-septic patients and healthy controls [55, 59, 66].

The association between sICAM-1 levels and sepsis severity was variable. Seven studies investigated this association, with four studies reporting higher sICAM-1 levels with increasing severity of sepsis [59, 64, 68, 77] and three negative studies [53, 61, 65].

Association with clinical outcome

Eleven studies reported data on mortality. Five of these studies reported that increasing sICAM-1 levels correlated with mortality [55, 58, 59, 68, 77], but six studies found no such correlation [53, 56, 57, 61, 65, 73]. One study found a trend towards increased mortality with increasing sICAM-1 levels over time [55].

Two studies evaluated the discriminative characteristics of sICAM-1 [51, 58]. Weigand et al. reported that a sICAM-1 threshold of 800 ng/ml could differentiate survivors from non-survivors with a sensitivity and specificity of 74.1%, although this value was derived from a small sample of 14 post-surgical patients with relatively high mortality (50%) [58]. Shapiro reported on a group of 221 patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected infections, of which 208 had sepsis of varying severity. The presenting sICAM-1 value predicted mortality with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.72 (95% CI (0.57 to 0.870)). However, a cutoff value was not reported [77].

Several studies reported moderate to poor correlation of sICAM-1 with the degree of severity of illness or number of organ failures as defined by APACHE II, SOFA, Multiple Organ Failure Score and Simplified Acute Physiology Score [59, 68, 73, 77].

One study reported varying kinetics of sICAM-1 according to age: In 30 patients with postoperative sepsis, Boldt et al. reported that older patients had higher sICAM-1 levels than younger patients (P < 0.05), and sICAM-1 tended to increase over time in older patients while decreasing over time in younger patients [60].

Soluble VCAM-1 (sVCAM-1)

We identified 12 studies evaluating sVCAM-1 (see Table 3-Studies Evaluating sVCAM-1) in sepsis. These studies evaluated sVCAM-1 in emergency department patients [51], postoperative patients [55, 63], patients admitted to ICU [56, 62], critically-ill trauma patients [60] and patients with sepsis [64, 65, 69, 78]. Three studies compared sVCAM-1 levels with healthy control groups [55, 65, 78].

Association with sepsis

Six studies reported that sVCAM-1 levels were significantly greater in patients with sepsis than in healthy controls [65, 78], trauma patients [62, 63], non-infected patients [77] and patients with multiple organ failure due to causes other than sepsis [64]. Four studies reported that sVCAM-1 levels effectively differentiated septic from non-septic patients [62–64, 77], but one study reported sVCAM-1 levels were not significantly different between septic patients, postoperative patients and healthy controls [55]. One study reported higher sVCAM-1 levels in patients with shock due to sepsis compared to other forms of shock [52].

Three studies attempted to correlate sVCAM-1 with increasing sepsis severity [64, 65, 77]. Shapiro et al. found a moderate degree of correlation with severe sepsis with an area under the ROC curve of 0.60 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.69) [77]. Cowley et al. reported that baseline and peak values of sVCAM-1 were higher in ICU patients with severe sepsis than in uncomplicated sepsis [65]. Conversely, another study reported that sVCAM-1 was not different in septic patients with or without organ failure [64].

Association with clinical outcome

Six of the 10 identified studies examined mortality outcomes, with 2 studies reporting an association between higher sVCAM-1 levels and mortality [55, 77], and 4 studies showing no significant correlation with mortality in patients with ARDS [56], gram-positive sepsis [78], and septic patients admitted to ICU [65, 69]. Hofer et al. found no correlation between baseline sVCAM-1 and mortality in septic patients but reported significantly higher sVCAM-1 levels at 48 and 120 hours in non-survivors compared to survivors.

Only one study addressed correlation of sVCAM-1 with clinical severity scores, and reported modest correlation with SOFA and APACHE II [77].

Two studies reported variability of sVCAM-1 in sepsis across different patient populations [64, 69]. Presterl et al. investigated the difference of sVCAM-1 level in Candida sepsis compared to bacterial sepsis, and found that sVCAM-1 was higher in Candida sepsis at days 1, 7 and 14 [69]. Similar to sICAM-1, Endo et al. found higher sVCAM-1 levels with increasing age, and observed that the dynamics of serial sVCAM-1 were different in patients stratified by age. Specifically, sVCAM-1 values increased over the course of sepsis time in older patients and decreased in younger patients [64].

One study found that sVCAM-1 was not associated with left ventricular size or function in patients with sepsis or septic shock [76].

Soluble E-selectin

Twenty-three studies were identified that evaluated sE-selectin as a biomarker in sepsis (see Table 4-Studies Evaluating sE-selectin-1).

Association with sepsis

The majority of identified studies reported higher levels of sE-selectin in sepsis compared to healthy controls or other patient groups without sepsis. Ten studies specifically reported significantly elevated sE-selectin levels in sepsis when compared with healthy controls [54, 58, 59, 65, 66, 71, 72, 78–80]. Geppert et al. reported higher sE-selectin levels in patients with SIRS following cardiopulmonary resuscitation compared to controls [74]. sE-selectin was also reported to be significantly higher in septic patients compared to trauma patients [62, 63, 66], ICU controls [59, 79], patients with infection but without systemic sepsis [61, 77], patients with shock from other causes [52], and patients with multiple organ failure without infection [64]. Hynninen et al. concluded that sE-selectin values were not statistically different in patients with severe sepsis from those with severe acute pancreatitis [70].

Association with clinical outcome

The reported association of sE-selectin and disease severity has been inconsistent. Five studies showed a correlation between the marker and increasing sepsis severity [59, 61, 65, 77, 79], although three studies did not find a significant correlation [64, 71, 73].

Thirteen of the identified studies evaluated the association between sE-selectin and mortality, with nine studies reporting a significant positive correlation [59, 61, 69, 73–75, 77–79] and four studies reporting no correlation [56, 58, 65, 70]. Among the studies reporting positive association, there was significant heterogeneity in the strength and type of association. One study of ICU patients with severe sepsis and septic shock reported that baseline sE-selectin-1 levels were higher in non-survivors than survivors, but the difference existed only for the first three days of sepsis [59]. In contrast, two other studies demonstrated a more persistent divergence of sE-selectin-1 between survivors and non-survivors of sepsis: Knapp et al. reported that sE-selectin-1 remained significantly elevated in non-survivors compared to survivors throughout the first seven days of sepsis [78], while Egerer reported that sE-selectin peaked in survivors of sepsis on the second day and decreased thereafter, whereas it continued to rise in patients who subsequently died [61]. One other study found that sE-selectin-1 predicted mortality in patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected infections, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.65 [51].

Only a few studies examined correlation between sE-selectin-1 and clinical severity of illness scores, and none found strong correlations. Shapiro et al. showed that sE-selectin correlated modestly with SOFA and APACHE-II [51]. Hynnien et al. reported that levels of sE-selectin were higher in patients with a SOFA score ≥ 10 compared to individuals with a score less than 10 [70]. sE-Selectin was also reported to correlate moderately or poorly with SAPSII [59, 73] and MOF score [59, 79].

Three studies evaluated variability in sE-selectin levels in different patient groups [60, 69, 79]. Boldt et al. showed sE-selectin levels in septic patients increased across age groups [60]. Cummings et al. showed higher levels in bacteremic sepsis than in non-bacteremic sepsis [79], and Presterl et al. found higher levels of sE-selectin in bacterial sepsis than in Candida sepsis [69].

Endocan

Two prospective observational studies were identified evaluating endocan as a biomarker in sepsis [23, 53] (see Table 5-Studies Evaluating Endocan).

Association with sepsis

Both studies reported that serum endocan was increased in septic patients. Schepereel et al. reported in their prospective study that endocan levels were higher in patients with sepsis than in patients with SIRS or healthy controls [53]. Bechard et al. showed that endocan levels were higher in patients with septic shock than in healthy controls [23].

Association with clinical outcome

Scherpereel et al. reported that mean endocan levels were higher in patients with septic shock than in patients with severe sepsis or sepsis. Furthermore, endocan levels measured at ICU admission were higher in non-survivors than in patients who were alive at 10 days. Using a threshold of 6.2 ng/ml, the sensitivity and specificity of endocan for predicting mortality were 75% and 84% respectively [53].

Mediators of permeability and vasomotor tone

We identified seven studies that examined soluble VEGF (see Table 6-Studies evaluating VEGF), two studies examining soluble FLT (Table 7-Studies Evaluating sFLT) and four studies examining endothelin-1 as biomarkers in sepsis (see Table 8-Studies Evaluating Endothelin-1). All but two were prospective studies, with two secondary analyses of previously conducted cohort studies [45, 81]. Patients recruited were emergency room patients with suspected infection [51, 77] or ICU patients [42, 45, 51, 81–88].

Soluble VEGF

Four studies reported a positive association with sepsis, with higher levels in septic patients compared with non-septic critically ill patients [77, 83, 84] and healthy controls [82]. In contrast, Van der Heijden et al. did not find a significant difference in soluble VEGF between septic and non-septic ICU patients [45] and Kumpers et al. reported lower serum VEGF levels in patients with sepsis compared to healthy controls [42]. Van der Flier et al. reported significantly elevated VEGF levels in non-survivors compared with survivors [83], in contrast to Karlsson et al. who reported significantly lower VEGF levels in non-survivors [82].

Soluble FLT (sFlt)

Both studies reporting sFLT were prospective studies from the same centre, studying emergency room patients with suspected infections, with non-infected patients serving as controls. There was some overlap between the two studies, with some patients reported in both cohorts. sFLT was shown to be elevated with increasing severity of illness [77], and was also predictive of severe sepsis and mortality, both upon presentation and longitudinally during hospitalization [51].

Endothelin-1

Two studies reported that endothelin-1 was significantly elevated in patients with sepsis compared with healthy controls [86, 87]. An additional two studies reported a correlation with severity of illness as defined by other biomarkers [85] or ACCP/SCCM criteria [81]. There was no documented association between endothelin-1 levels and mortality in the one study that examined this outcome [81].

Mediators of coagulation

We identified 14 relevant studies studying von Willebrand Factor (vWF) and sepsis (see Table 9-Studies Evaluating von Willebrand Factor). All studies reported assays of either VWF:Ag and/or VWF:RCo activity. Four studies presented data on ADAMTS13 (see Table 10-Studies Evaluating ADAMTS13), which reported either ADAMTS13 antigen levels or ADAMTS13 activity.

Von Willebrand factor (vWF)

Association with sepsis

Eight studies examined the capability of circulating vWF levels to differentiate patients with sepsis from patients with other illnesses. Two studies found that vWF levels were significantly higher in septic patients compared to patients with systemic inflammation from other causes [89, 90], other non-septic critically-ill patients [45, 53, 90], and healthy controls [59, 89]. Two studies reported higher levels in patients with sepsis than in patients with SIRS or healthy controls, but the differences did not reach statistical significance [91–93]. In a cohort of patients with ALI/ARDS, Ware et al. reported that vWF was significantly increased in septic patients compared with those without sepsis (P < 0.05) [94].

Hovinga et al. in a secondary analysis of a clinical trial, reported that vWF activity was significantly higher in septic patients than in healthy controls, but vWF was not correlated with sepsis severity or survival [95]. Two other studies found a significant correlation between VWF and sepsis severity [59, 94].

Association with clinical outcome

Four studies looked at its correlation with ALI/ARDS, with two studies showing its ability to differentiate those with ALI/ARDS from those without [45, 96], and two studies showing that it is not predictive of ALI/ARDS [97, 98].

Ten of the identified studies presented mortality data, with six studies showing a significant correlation of vWF with mortality [45, 53, 59, 90, 94, 96], with one study reporting a plasma vWF:Ag of 450% the upper normal limit predicted death with a sensitivity of 44% and a specificity of 91% [94]. Four studies did not find a significant correlation with mortality [89, 91, 93, 95].

ADAMTS13

Three studies showed that ADAMTS13 is significantly lower in sepsis than other critically ill nonseptic patients [89–91]. One study showed significant correlation with disease severity [91], while a second did not [95]. Three studies showed ADAMTS13 levels correlated with mortality [89–91], although one study did not find a significant correlation [95].

Discussion

We report a comprehensive and exhaustive systematic review of biomarkers reflecting endothelial activation for the diagnosis, triage and prognostication of sepsis in humans. The reviewed literature demonstrates positive associations between multiple EC-derived molecules and sepsis, supporting the critical role of EC activation in the septic response. Multiple other studies also reported positive associations for mortality and severity of illness, although these results were less consistent than for sepsis per se. Very few studies, however, reported thresholds or receiver operating characteristics that would establish these molecules as clinically-relevant biomarkers in sepsis.

Of the potential biomarkers reviewed, the angiopoeitin-1/2 system may hold the most promise. Multiple studies reported consistent associations between elevations in circulating Ang-2 levels and sepsis in varied samples of critically ill patients. All studies evaluating Ang-2 used standard sepsis definitions, with consistent association between Ang-2 levels and sepsis, as well as relatively consistent associations between Ang-2 and other clinical outcomes. The strength of association is also supported in the identified studies by: (1) a demonstrable dose-response relationship with higher Ang-2 levels in severe sepsis and organ dysfunction, and increasing with increasing severity of illness, and (2) a temporal progression with Ang-2 levels increasing over time in those patients who developed sepsis and in patients with increasing severity of sepsis as defined by SIRS, sepsis and septic shock. Unfortunately, no studies provided a cut point or threshold that would make Ang-2 clinically useful as a biomarker in the diagnosis or stratification of patients presenting with presumed sepsis.

One general limitation with all of the identified studies is the lack of standardized assays for the studied molecules. Very few studies reported threshold values for prognostic analysis or receiver operating characteristics of the potential biomarkers. Furthermore, almost all studies were either single centre or single laboratory, and most assays were non-standardized ELISAs, and thus the absolute values reported in each study may vary according to the type of assay, as well as the type of sample used (for example, plasma vs. serum). These issues led to important limitations in the generalizability and strength of inference that can be drawn from the identified studies. Where possible, we have reported absolute values in the tables to allow readers to appreciate the scope of variation, as well as absolute differences in levels between groups.

There are several limitations to our study. We searched for known endothelial-derived markers by name, and it is possible that other novel markers were missed. We attempted to address this limitation by hand-searching the reference list of identified studies to include all relevant studies of selected endothelial-derived markers. Many of the identified publications are single-centre studies or retrospective analyses of previously collected specimens, which limit generalizability to other jurisdictions and populations. As previously mentioned, lack of standardization in the reported assays makes quantitative comparison of a biomarker across studies impossible, and thus we can only report similarities in the direction and relative magnitude of association across studies.

The identified studies were most commonly small prospective or retrospective cohort studies evaluating levels of a potential biomarker in patients with sepsis and a comparative control group. Almost all studies used established consensus criteria for the definition of sepsis to limit misclassification of patients. There was significant heterogeneity in patient populations across studies, however, including patients with presumed sepsis identified in any one of the emergency department, medical ward and medical, surgical and trauma intensive care units. It is conceivable that the receiver operating characteristics of any given biomarker may vary according to the differential inflammatory state, concurrent injuries and pathophysiology of these different patient groups.

If EC-derived biomarkers are to become clinically useful, future work will require standardization of analytical techniques and rigorous evaluation of receiver operating characteristics to define the role and reliability of these molecules. Although some recent studies reported receiver operating characteristics or threshold biomarker levels, the lack of standard assays limits the interpretation and clinical utility of these efforts. Future work must include: (1) the description of the operating characteristics of biomarkers, (2) the use of explicitly defined threshold serum levels, (3) measured with a standardized assay.

It may be impossible to achieve the high degree of sensitivity and specificity required for clinical diagnosis with a single biomarker assay, and a multiplexed combination of markers may be necessary to improve predictive value and clinical utility of biomarkers. Careful selection and combinations of biomarkers with relative specificity to disease states (for example, the observed association between Ang-2 and ARDS/pulmonary leak, or the differential association of sVCAM and sE-Selectin in fungal sepsis) would be one way of improving the clinical utility of these novel molecules. Following identification of useful serum biomarker thresholds with standard assays, we speculate that evaluation of multiplexed biomarker panels may prove useful as a diagnostic strategy.

Given the epidemiologic rise of sepsis in both the developed [99] and developing world [100], novel diagnostics and therapeutics for sepsis are urgently needed, and endothelial-derived biomarkers will likely play a crucial role.

Conclusions

We report a systematic review of the published literature and findings that multiple molecules reflecting endothelial activation are correlated with the presence of sepsis in humans. We also found variable degrees of correlation between biomarkers and other clinical outcomes. The clinical utility or application of these molecules as biomarkers in sepsis, however, is limited by a lack of standardization in analytical assays, a lack of data regarding receiver operating characteristics and, in the few cases where thresholds have been reported, a lack of validation in representative patient populations.

Key messages

-

Multiple molecules reflecting endothelial activation are correlated with the presence of sepsis in humans and other clinically important outcomes.

-

The clinical utility or application of these molecules as biomarkers in sepsis; however, is limited by a lack of standardization in analytical assays, a lack of data regarding receiver operating characteristics and a lack of validation.

-

The consistent association with sepsis, demonstrable dose-response relationship, and temporal progression in patients who develop sepsis make Angiopoietin-2 an attractive potential biomarker in sepsis.

-

Future research should focus on standardization of assays and identification of cut points or thresholds that make biomarkers clinically useful in the diagnosis or stratification of patients presenting with presumed sepsis.

-

Evaluation of multiplexed panels with biomarkers of differential response characteristics may prove useful as a diagnostic strategy.

Abbreviations

- ACCP:

-

American College of Chest Physicians

- ADAMTS13:

-

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, Member 13

- ALI:

-

Acute Lung Injury

- Ang 1/2:

-

Angiopoeitin 1/2

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- ARDS:

-

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- EC:

-

endothelial cell

- ED:

-

emergency department

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- MOF:

-

Multiple Organ Failure

- SAPS:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- SCCM:

-

Society of Critical Care Medicine

- s-Flt:

-

soluble Flt (soluble Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor receptor)

- sICAM-1:

-

Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1

- SIRS:

-

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- sVCAM-1:

-

Vascular Cell Adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF:

-

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- vWF:

-

von Willebrand Factor

- vWFA:

-

von Willebrand Factor antigen

- vWFRCo:

-

von Willebrand Factor ristocetin cofactor.

References

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ: Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 1992, 101: 1644-1655. 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G: 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: 1250-1256. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR: Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1303-1310. 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002

Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001, 69: 89-95.

Pierrakos C, Vincent JL: Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care 2010, 14: R15. 10.1186/cc8872

Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE: Endothelial cell apoptosis in sepsis: a case of habeas corpus? Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 901-902. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000115264.93926.EC

Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Karl IE: Endothelial cell apoptosis in sepsis. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: S225-228. 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00009

Hemmer CJ, Vogt A, Unverricht M, Krause R, Lademann M, Reisinger EC: Malaria and bacterial sepsis: similar mechanisms of endothelial apoptosis and its prevention in vitro. Crit Care Med 2008, 36: 2562-2568. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818441ee

Hack CE, Zeerleder S: The endothelium in sepsis: source of and a target for inflammation. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: S21-27.

Matsuda N, Teramae H, Yamamoto S, Takano K, Takano Y, Hattori Y: Increased death receptor pathway of apoptotic signaling in septic mouse aorta: effect of systemic delivery of FADD siRNA. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010, 298: H92-101. 10.1152/ajpheart.00069.2009

Reinhart K, Bayer O, Brunkhorst F, Meisner M: Markers of endothelial damage in organ dysfunction and sepsis. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: S302-312. 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00021

Schouten M, Wiersinga WJ, Levi M, van der Poll T: Inflammation, endothelium, and coagulation in sepsis. J Leukoc Biol 2008, 83: 536-545.

Aird WC: The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood 2003, 101: 3765-3777. 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1887

Vallet B: Bench-to-bedside review: endothelial cell dysfunction in severe sepsis: a role in organ dysfunction? Crit Care 2003, 7: 130-138. 10.1186/cc1864

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ: GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336: 924-926. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Trzeciak S, Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Pusateri AE, Arnold RC, Rizzuto M, Arora T, Parrillo JE, Dellinger RP, Emergency Medicine Shock Research Network (EMShockNet) investigators: A prospective multicenter cohort study of the association between global tissue hypoxia and coagulation abnormalities during early sepsis resuscitation. Crit Care Med 2010, 38: 1092-1100. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cf6fbc

Ganter MT, Cohen MJ, Brohi K, Chesebro BB, Staudenmayer KL, Rahn P, Christiaans SC, Bir ND, Pittet JF: Angiopoietin-2, marker and mediator of endothelial activation with prognostic significance early after trauma? Ann Surg 2008, 247: 320-326. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318162d616

Cepkova M, Brady S, Sapru A, Matthay MA, Church G: Biological markers of lung injury before and after the institution of positive pressure ventilation in patients with acute lung injury. Critical Care 2006, 10: R126. 10.1186/cc5037

Yano K, Liaw PC, Mullington JM, Shih SC, Okada H, Bodyak N, Kang PM, Toltl L, Belikoff B, Buras J, Simms BT, Mizgerd JP, Carmeliet P, Karumanchi SA, Aird WC: Vascular endothelial growth factor is an important determinant of sepsis morbidity and mortality. J Exp Med 2006, 203: 1447-1458. 10.1084/jem.20060375

Megarbane B, Marchal P, Marfaing-Koka A, Belliard O, Jacobs F, Chary I, Brivet FG: Increased diffusion of soluble adhesion molecules in meningitis, severe sepsis and systemic inflammatory response without neurological infection is associated with intrathecal shedding in cases of meningitis. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 867-874. 10.1007/s00134-004-2253-1

Fujimi S, Ogura H, Tanaka H, Koh T, Hosotsubo H, Nakamori Y, Kuwagata Y, Shimazu T, Sugimoto H: Activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes enhance production of leukocyte microparticles with increased adhesion molecules in patients with sepsis. J Trauma 2002, 52: 443-448. 10.1097/00005373-200203000-00005

Poeze M, Ramsay G, Buurman WA, Greve JW, Dentener M, Takala J: Increased hepatosplanchnic inflammation precedes the development of organ dysfunction after elective high-risk surgery. Shock 2002, 17: 451-458. 10.1097/00024382-200206000-00002

Bechard D, Meignin V, Scherpereel A, Oudin S, Kervoaze G, Bertheau P, Janin A, Tonnel A, Lassalle P: Characterization of the secreted form of endothelial-cell-specific molecule 1 by specific monoclonal antibodies. J Vasc Res 2000, 37: 417-425. 10.1159/000025758

Giannoudis PV, Smith RM, Banks RE, Windsor AC, Dickson RA, Guillou PJ: Stimulation of inflammatory markers after blunt trauma. Br J Surg 1998, 85: 986-990. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00770.x

McGill SN, Ahmed NA, Christou NV: Increased plasma von Willebrand factor in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome is derived from generalized endothelial cell activation. Crit Care Med 1998, 26: 296-300. 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00031

Kneidinger R, Bahrami S, Redl H, Schlag G, Robinson M, Weichselbraun I, Cremer J: Evaluation of a soluble E-selectin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay under posttraumatic conditions. J Lab Clin Med 1996, 128: 520-523. 10.1016/S0022-2143(96)90050-5

Hesselvik JF, Blomback M, Brodin B, Maller R: Coagulation, fibrinolysis, and kallikrein systems in sepsis: relation to outcome. Crit Care Med 1989, 17: 724-733. 10.1097/00003246-198908000-00002

van der Heijden M, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VW, Groeneveld AB: The interaction of soluble Tie2 with angiopoietins and pulmonary vascular permeability in septic and nonseptic critically ill patients. Shock 2010, 33: 263-268. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181b2f978

Kumpers P, Hafer C, David S, Hecker H, Lukasz A, Fliser D, Haller H, Kielstein JT, Faulhaber-Walter R: Angiopoietin-2 in patients requiring renal replacement therapy in the ICU: relation to acute kidney injury, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and outcome. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 462-470. 10.1007/s00134-009-1726-7

Gando S, Kameue T, Matsuda N, Hayakawa M, Hoshino H, Kato H: Serial changes in neutrophil-endothelial activation markers during the course of sepsis associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Res 2005, 116: 91-100. 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.09.022

von Heymann C, Langenkamp J, Dubisz N, von Dossow V, Schaffartzik W, Kern H, Kox WJ, Spies C: Posttraumatic immune modulation in chronic alcoholics is associated with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. J Trauma 2002, 52: 95-103. 10.1097/00005373-200201000-00017

Grad S, Ertel W, Keel M, Infanger M, Vonderschmitt DJ, Maly FE: Strongly enhanced serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) after polytrauma and burn. Clin Chem Lab Med 1998, 36: 379-383. 10.1515/CCLM.1998.064

Rivers EP, Kruse JA, Jacobsen G, Shah K, Loomba M, Otero R, Childs EW: The influence of early hemodynamic optimization on biomarker patterns of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 2016-2024. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000281637.08984.6E

Fang XL, Fang Q, Cai GL, Yan J: [Effect of fluid resuscitation on adhesion molecule and hemodynamics in patients with severe sepsis]. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2006, 18: 539-541.

Boldt J, Papsdorf M, Piper SN, Rothe A, Hempelmann G: Continuous heparinization and circulating adhesion molecules in the critically ill. Shock 1999, 11: 13-18.

Kuang X, Ma K, Duan T: [The significance of postburn changes in plasma levels of ICAM-1, IL-10 and TNFalpha during early postburn stage in burn patients]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi 2002, 18: 302-304.

Li PJ, Yang XH, Zhang LP, Cao W, Qin J, Yao W: [Clinical significance of soluble selectins and matrix metalloproteinases-9 in patients after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation]. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2004, 16: 137-141.

Orfanos SE, Kotanidou A, Glynos C, Athanasiou C, Tsigkos S, Dimopoulou I, Sotiropoulou C, Zakynthinos S, Armaganidis A, Papapetropoulos A, Roussos C: Angiopoietin-2 is increased in severe sepsis: correlation with inflammatory mediators. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 199-206. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251640.77679.D7

Siner JM, Bhandari V, Engle KM, Elias JA, Siegel MD: Elevated serum angiopoietin 2 levels are associated with increased mortality in sepsis. Shock 2009, 31: 348-353. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318188bd06

Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Kanellakopoulou K, Pelekanou A, Tsaganos T, Kotzampassi K: Kinetics of angiopoietin-2 in serum of multi-trauma patients: correlation with patient severity. Cytokine 2008, 44: 310-313. 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.09.003

Kranidioti H, Orfanos SE, Vaki I, Kotanidou A, Raftogiannis M, Dimopoulou I, Kotsaki A, Savva A, Papapetropoulos A, Armaganidis A, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ: Angiopoietin-2 is increased in septic shock: evidence for the existence of a circulating factor stimulating its release from human monocytes. Immunol Lett 2009, 125: 65-71. 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.06.006

Kumpers P, Lukasz A, David S, Horn R, Hafer C, Faulhaber-Walter R, Fliser D, Haller H, Kielstein JT: Excess circulating angiopoietin-2 is a strong predictor of mortality in critically ill medical patients. Crit Care 2008, 12: R147. 10.1186/cc7130

Parikh SM, Mammoto T, Schultz A, Yuan HT, Christiani D, Karumanchi SA, Sukhatme VP: Excess circulating angiopoietin-2 may contribute to pulmonary vascular leak in sepsis in humans. PLoS Med 2006, 3: e46. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030046

Davis JS, Yeo TW, Piera KA, Woodberry T, Celermajer DS, Stephens DP, Anstey NM: Angiopoietin-2 is increased in sepsis and inversely associated with nitric oxide-dependent microvascular reactivity. Crit Care 2010, 14: R89. 10.1186/cc9020

van der Heijden M, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Koolwijk P, van Hinsbergh VW, Groeneveld AB: Angiopoietin-2, permeability oedema, occurrence and severity of ALI/ARDS in septic and non-septic critically ill patients. Thorax 2008, 63: 903-909. 10.1136/thx.2007.087387

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE: APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985, 13: 818-829. 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG: The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996, 22: 707-710. 10.1007/BF01709751

Ricciuto DR, dos Santos CC, Hawkes M, Toltl LJ, Conroy AL, Rajwans N, Lafferty EI, Cook DJ, Fox-Robichaud A, Kahnamoui K, Kain KC, Liaw PC, Liles WC: Angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 as clinically informative prognostic biomarkers of morbidity and mortality in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 702-710. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206d285

Ebihara I, Hirayama K, Nagai M, Kakita T, Sakai K, Tajima R, Sato C, Kurosawa H, Togashi A, Okada A, Usui J, Yamagata K, Kobayashi M: Angiopoietin balance in septic shock patients with acute lung injury: effect of direct hemoperfusion with polymyxin B-immobilized fiber. Ther Apher Dial 2011, 15: 349-354.

Page AV, Kotb M, McGeer A, Low DE, Kain KC, Liles WC: Systemic dysregulation of angiopoietin-1/2 in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2011, 52: e157-161. 10.1093/cid/cir125

Shapiro N, Schuetz P, Yano K, Sorasaki M, Parikh SM, Jones AE, Trzeciak S, Ngo L, Aird WC: The association of endothelial cell signaling, severity of illness, and organ dysfunction in sepsis. Crit Care 2010, 14: R182. 10.1186/cc9290

Schuetz P, Jones AE, Aird WC, Shapiro NI: Endothelial cell activation in emergency department patients with sepsis-related and non-sepsis-related hypotension. Shock 2011, 36: 104-108. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31821e4e04

Scherpereel A, Depontieu F, Grigoriu B, Cavestri B, Tsicopoulos A, Gentina T, Jourdain M, Pugin J, Tonnel AB, Lassalle P: Endocan, a new endothelial marker in human sepsis. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 532-537. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000198525.82124.74

Stief TW, Ijagha O, Weiste B, Herzum I, Renz H, Max M: Analysis of hemostasis alterations in sepsis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2007, 18: 179-186. 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328040bf9a

Hofer S, Brenner T, Bopp C, Steppan J, Lichtenstern C, Weitz J, Bruckner T, Martin E, Hoffmann U, Weigand MA: Cell death serum biomarkers are early predictors for survival in severe septic patients with hepatic dysfunction. Crit Care 2009, 13: R93. 10.1186/cc7923

Kinoshita M, Ono S, Mochizuki H: Neutrophil-related inflammatory mediators in septic acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Intensive Care Med 2002, 17: 308-316. 10.1177/0885066602238033

Paterson RL, Galley HF, Dhillon JK, Webster NR: Increased nuclear factor kappa B activation in critically ill patients who die. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 1047-1051. 10.1097/00003246-200004000-00022

Weigand MA, Schmidt H, Pourmahmoud M, Zhao Q, Martin E, Bardenheuer HJ: Circulating intercellular adhesion molecule-1 as an early predictor of hepatic failure in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 1999, 27: 2656-2661. 10.1097/00003246-199912000-00008

Kayal S, Jais JP, Aguini N, Chaudiere J, Labrousse J: Elevated circulating E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and von Willebrand factor in patients with severe infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 157: 776-784.

Boldt J, Muller M, Heesen M, Papsdorf M, Hempelmann G: Does age influence circulating adhesion molecules in the critically ill? Crit Care Med 1997, 25: 95-100. 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00019

Egerer K, Rohr U, Krausch D, Kox W: The circulating adhesion molecules sICAM-1 and sE-selection in patients with sepsis. Anaesthesist 1997, 46: 592-598. 10.1007/s001010050442

Takakuwa T, Endo S, Inada K, Kasai T, Yamada Y, Ogawa M: Assessment of inflammatory cytokines, nitrate/nitrite, type II phospholipase A2, and soluble adhesion molecules in systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol 1997, 98: 43-52.

Boldt J, Muller M, Kuhn D, Linke LC, Hempelmann G: Circulating adhesion molecules in the critically ill: a comparison between trauma and sepsis patients. Intensive Care Med 1996, 22: 122-128. 10.1007/BF01720718

Endo S, Inada K, Kasai T, Takakuwa T, Yamada Y, Koike S, Wakabayashi G, Niimi M, Taniguchi S, Yoshida M: Levels of soluble adhesion molecules and cytokines in patients with septic multiple organ failure. J Inflamm 1995, 46: 212-219.

Cowley HC, Heney D, Gearing AJ, Hemingway I, Webster NR: Increased circulating adhesion molecule concentrations in patients with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med 1994, 22: 651-657. 10.1097/00003246-199404000-00022

Moss M, Gillespie MK, Ackerson L, Moore FA, Moore EE, Parsons PE: Endothelial cell activity varies in patients at risk for the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 1996, 24: 1782-1786. 10.1097/00003246-199611000-00004

Nakae H, Endo S, Inada K, Takakuwa T, Kasai T: Changes in adhesion molecule levels in sepsis. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol 1996, 91: 329-338.

Sessler CN, Windsor AC, Schwartz M, Watson L, Fisher BJ, Sugerman HJ, Fowler AA: Circulating ICAM-1 is increased in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 151: 1420-1427.

Presterl E, Lassnigg A, Mueller-Uri P, El-Menyawi I, Graninger W: Cytokines in sepsis due to Candida albicans and in bacterial sepsis. Eur Cytokine Netw 1999, 10: 423-430.

Hynninen M, Valtonen M, Markkanen H, Vaara M, Kuusela P, Jousela I, Piilonen A, Takkunen O: Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist and E-selectin concentrations: a comparison in patients with severe acute pancreatitis and severe sepsis. J Crit Care 1999, 14: 63-68. 10.1016/S0883-9441(99)90015-1

Takala A, Jousela I, Jansson SE, Olkkola KT, Takkunen O, Orpana A, Karonen SL, Repo H: Markers of systemic inflammation predicting organ failure in community-acquired septic shock. Clin Sci 1999, 97: 529-538. 10.1042/CS19990073

Osmanovic N, Romijn FPHTM, Joop K, Sturk A, Nieuwland R: Soluble selectins in sepsis: Microparticle-associated, but only to a minor degree. Thromb Haemost 2000, 84: 731-732.

Froon AH, Bonten MJ, Gaillard CA, Greve JW, Dentener MA, de Leeuw PW, Drent M, Stobberingh EE, Buurman WA: Prediction of clinical severity and outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Comparison of simplified acute physiology score with systemic inflammatory mediators. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 1998, 158: 1026-1031.

Geppert A, Zorn G, Karth GD, Haumer M, Gwechenberger M, Koller-Strametz J, Heinz G, Huber K, Siostrzonek P: Soluble selectins and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 2360-2365.

Simons RK, Hoyt DB, Winchell RJ, Rose RM, Holbrook T: Elevated selectin levels after severe trauma: a marker for sepsis and organ failure and a potential target for immunomodulatory therapy. J Trauma 1996, 41: 653-662. 10.1097/00005373-199610000-00010

Furian T, Aguiar C, Prado K, Ribeiro RV, Becker L, Martinelli N, Clausell N, Rohde LE, Biolo A: Ventricular dysfunction and dilation in severe sepsis and septic shock: Relation to endothelial function and mortality. J Crit Care 2011, in press.

Shapiro NI, Yano K, Okada H, Fischer C, Howell M, Spokes KC, Ngo L, Angus DC, Aird WC: A prospective, observational study of soluble FLT-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor in sepsis. Shock 2008, 29: 452-457. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31815072c1

Knapp S, Thalhammer F, Locker GJ, Laczika K, Hollenstein U, Frass M, Winkler S, Stoiser B, Wilfing A, Burgmann H: Prognostic value of MIP-1 alpha, TGF-beta 2, sELAM-1, and sVCAM-1 in patients with gram-positive sepsis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1998, 87: 139-144. 10.1006/clin.1998.4523

Cummings CJ, Sessler CN, Beall LD, Fisher BJ, Best AM, Fowler AA: Soluble E-selectin levels in sepsis and critical illness. Correlation with infection and hemodynamic dysfunction. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 1997, 156: 431-437.

Newman W, Beall LD, Carson CW, Hunder GG, Graben N, Randhawa ZI, Gopal TV, Wiener-Kronish J, Matthay MA: Soluble E-selectin is found in supernatants of activated endothelial cells and is elevated in the serum of patients with septic shock. J Immunol 1993, 150: 644-654.

Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Bergmann A, Muller B: Circulating precursor levels of endothelin-1 and adrenomedullin, two endothelium-derived, counteracting substances, in sepsis. Endothelium 2007, 14: 345-351. 10.1080/10623320701678326

Karlsson S, Pettila V, Tenhunen J, Lund V, Hovilehto S, Ruokonen E, Finnsepsis Study G: Vascular endothelial growth factor in severe sepsis and septic shock. Anesth Analg 2008, 106: 1820-1826. 10.1213/ane.0b013e31816a643f

van der Flier M, van Leeuwen HJ, van Kessel KP, Kimpen JL, Hoepelman AI, Geelen SP: Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor in severe sepsis. Shock 2005, 23: 35-38. 10.1097/01.shk.0000150728.91155.41

Rafat N, Hanusch C, Brinkkoetter PT, Schulte J, Brade J, Zijlstra JG, van der Woude FJ, van Ackern K, Yard BA, Beck GC: Increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells in septic patients: correlation with survival. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 1677-1684. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269034.86817.59

Piechota M, Banach M, Irzmanski R, Barylski M, Piechota-Urbanska M, Kowalski J, Pawlicki L: Plasma endothelin-1 levels in septic patients. J Intensive Care Med 2007, 22: 232-239. 10.1177/0885066607301444

Weitzberg E, Lundberg JM, Rudehill A: Elevated plasma levels of endothelin in patients with sepsis syndrome. Circ Shock 1991, 33: 222-227.

Pittet JF, Morel DR, Hemsen A, Gunning K, Lacroix JS, Suter PM, Lundberg JM: Elevated plasma endothelin-1 concentrations are associated with the severity of illness in patients with sepsis. Ann Surg 1991, 213: 261-264. 10.1097/00000658-199103000-00014

Yang K-Y, Liu K-T, Chen Y-C, Chen C-S, Lee Y-C, Perng R-P, Feng J-Y: Plasma soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 levels predict outcomes of pneumonia-related septic shock patients: a prospective observational study. Critical Care 2011, 15: R11. 10.1186/cc9412

Claus RA, Bockmeyer CL, Budde U, Kentouche K, Sossdorf M, Hilberg T, Schneppenheim R, Reinhart K, Bauer M, Brunkhorst FM, Losche W: Variations in the ratio between von Willebrand factor and its cleaving protease during systemic inflammation and association with severity and prognosis of organ failure. Thromb Haemost 2009, 101: 239-247.

Bockmeyer CL, Claus RA, Budde U, Kentouche K, Schneppenheim R, Losche W, Reinhart K, Brunkhorst FM: Inflammation-associated ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes formation of ultra-large von Willebrand factor. Haematologica 2008, 93: 137-140. 10.3324/haematol.11677

Martin K, Borgel D, Lerolle N, Feys HB, Trinquart L, Vanhoorelbeke K, Deckmyn H, Legendre P, Diehl JL, Baruch D: Decreased ADAMTS-13 (A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 repeats) is associated with a poor prognosis in sepsis-induced organ failure. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 2375-2382. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000284508.05247.B3

Garcia-Fernandez N, Montes R, Purroy A, Rocha E: Hemostatic disturbances in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and associated acute renal failure (ARF). Thromb Res 2000, 100: 19-25. 10.1016/S0049-3848(00)00306-6

Lorente JA, Garcia-Frade LJ, Landin L, de Pablo R, Torrado C, Renes E, Garcia-Avello A: Time course of hemostatic abnormalities in sepsis and its relation to outcome. Chest 1993, 103: 1536-1542. 10.1378/chest.103.5.1536

Ware LB, Conner ER, Matthay MA: von Willebrand factor antigen is an independent marker of poor outcome in patients with early acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 2325-2331. 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00016

Hovinga JAK, Zeerleder S, Kessler P, Romani de Wit T, van Mourik JA, Hack CE, ten Cate H, Reitsma PH, Wuillemin WA, Lammle B: ADAMTS-13, von Willebrand factor and related parameters in severe sepsis and septic shock. J Thromb Haemost 2007, 5: 2284-2290. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02743.x

Rubin DB, Wiener-Kronish JP, Murray JF, Green DR, Turner J, Luce JM, Montgomery AB, Marks JD, Matthay MA: Elevated von Willebrand factor antigen is an early plasma predictor of acute lung injury in nonpulmonary sepsis syndrome. J Clin Invest 1990, 86: 474-480. 10.1172/JCI114733

Bajaj MS, Tricomi SM: Plasma levels of the three endothelial-specific proteins von Willebrand factor, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and thrombomodulin do not predict the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 1999, 25: 1259-1266. 10.1007/s001340051054

Moss M, Ackerson L, Gillespie MK, Moore FA, Moore EE, Parsons PE: von Willebrand factor antigen levels are not predictive for the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 151: 15-20.

Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M: The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003, 348: 1546-1554. 10.1056/NEJMoa022139

Sankar J, Lodha R, Kabra SK: Management of septic shock: where do we stand? Indian J Pediatr 2008, 75: 1167-1169. 10.1007/S12098-008-0241-0

Yang KY, Liu KT, Chen YC, Chen CS, Lee YC, Perng RP, Feng JY: Plasma soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 levels predict outcomes of pneumonia-related septic shock patients: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 2011, 15: R11. 10.1186/cc9412

Bone RC, Fisher CJ Jr, Clemmer TP, Slotman GJ, Metz CA, Balk RA: Sepsis syndrome: a valid clinical entity. Methylprednisolone Severe Sepsis Study Group. Crit Care Med 1989, 17: 389-393. 10.1097/00003246-198905000-00002

Doyle RL, Szaflarski N, Modin GW, Wiener-Kronish JP, Matthay MA: Identification of patients with acute lung injury. Predictors of mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 152: 1818-1824.

Acknowledgements

WCL is the recipient of a Canada Research Chair (Infectious Diseases and Inflammation) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KX conceived of the study, participated in study design, participated in literature review and data extraction, and drafted the initial manuscript. WCL conceived of the study, participated in study design and provided critical revisions to the manuscript for intellectual content. JMS participated in study design, participated in literature review and data extraction, drafted the initial manuscript and provided critical revisions to the manuscript for intellectual content. SM participated in the literature review and data extraction, and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors participated in data synthesis and interpretation of results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Xing, K., Murthy, S., Liles, W.C. et al. Clinical utility of biomarkers of endothelial activation in sepsis-a systematic review. Crit Care 16, R7 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11145

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11145