Abstract

Background

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) confers considerable morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients, although few studies have focused on the critically ill population. The objective of this study was to understand current approaches to the prevention and diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) among patients in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Design

Mailed self-administered survey of ICU Directors in Canadian university affiliated hospitals.

Results

Of 29 ICU Directors approached, 29 (100%) participated, representing 44 ICUs and 681 ICU beds across Canada. VTE prophylaxis is primarily determined by individual ICU clinicians (20/29, 69.0%) or with a hematology consultation for challenging patients (9/29, 31.0%). Decisions are usually made on a case-by-case basis (18/29, 62.1%) rather than by preprinted orders (5/29, 17.2%), institutional policies (6/29, 20.7%) or formal practice guidelines (2/29, 6.9%). Unfractionated heparin is the predominant VTE prophylactic strategy (29/29, 100.0%) whereas low molecular weight heparin is used less often, primarily for trauma and orthopedic patients. Use of pneumatic compression devices and thromboembolic stockings is variable. Systematic screening for DVT with lower limb ultrasound once or twice weekly was reported by some ICU Directors (7/29, 24.1%) for specific populations. Ultrasound is the most common diagnostic test for DVT; the reference standard of venography is rarely used. Spiral computed tomography chest scans and ventilation–perfusion scans are used more often than pulmonary angiograms for the diagnosis of PE. ICU Directors recommend further studies in the critically ill population to determine the test properties and risk:benefit ratio of VTE investigations, and the most cost-effective methods of prophylaxis in medical–surgical ICU patients.

Interpretation

Unfractionated subcutaneous heparin is the predominant VTE prophylaxis strategy for critically ill patients, although low molecular weight heparin is prescribed for trauma and orthopedic patients. DVT is most often diagnosed by lower limb ultrasound; however, several different tests are used to diagnose PE. Fundamental research in critically ill patients is needed to help make practice evidence-based.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most serious manifestation of DVT is PE, which occurs in up to 1% of hospitalized patients and in 15% of patients at postmortem [1]. Critically ill patients are at increased risk of VTE due to their premorbid conditions, admitting diagnoses such as sepsis and trauma, and events and exposures in the ICU such as central venous catheterization, invasive tests and procedures, and drugs that potentiate immobility [2,3]. While autopsies have identified PE in 20–27% of ICU patients [4,5], most clinical studies of VTE in the critically ill focus on DVT. It is estimated that 90% of cases of PE originate in the deep venous system of the lower limbs [6].

Two cross-sectional studies at the time of admission to the ICU found a 10% prevalence of DVT diagnosed by lower limb ultrasonography [7,8]. The risk of DVT developing during the ICU stay was established in three longitudinal studies using systematic screening [5,9,10]. Among ICU patients who did not receive prophylaxis, 76% of whom were mechanically ventilated, radioactive fibrinogen scanning for 3–6 days identified DVT in 3/34 (9%) patients [5]. Among 100 medical ICU patients, 80% of whom were ventilated, Doppler ultrasound twice weekly identified DVT in 10/18 (56%) patients who received no prophylaxis, 17/43 (40%) who received unfrac-tionated subcutaneous heparin, and 6/18 (33%) who received pneumatic compression of the legs [9]. In a third study of 102 medical–surgical ICU patients who had duplex ultrasound during days 4–7 [10], DVT rates were 25, 19, and 7% in patients who received no prophylaxis, pneumatic compression, and unfractionated heparin, respectively. Trauma patients who do not receive prophylaxis, however, have DVT rates of 60%, as demonstrated by serial impedance plethys-mography and venography [11].

Two randomized trials have tested the efficacy of DVT prophylaxis in medical–surgical ICU patients. In 1982, 119 patients were randomized to receive unfractionated heparin (5000 U subcutaneously twice daily) or placebo [12]. Scanning with I125 fibrinogen for 5 days identified DVT in 13 and 29% of these patients, respectively (relative risk, 0.45; P < 0.05). More recently, 223 mechanically ventilated patients with an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were randomized to 0.14 or 0.6 ml nadroparin subcutaneously daily or placebo [13]. Duplex compression ultrasound performed weekly identified DVT in 16% of the low molecular weight heparin group and 28% in the control group (relative risk, 0.67; P < 0.05). There are, however, no direct comparisons of low molecular weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin in this population. This is not the case for trauma patients; in one landmark trial, Geerts et al identified DVT in 31% of patients randomized to receive enoxaparin compared with 44% in patients receiving unfractionated heparin (relative risk, 0.70; P < 0.05) [14].

The high risk of DVT and PE in critically ill patients, its potential morbidity and mortality, and the need for accurate diagnosis and effective prevention prompted a survey of Canadian ICU Directors. The five specific goals were to understand decisional responsibility for VTE prophylaxis, to understand the type of prophylaxis prescribed, to understand approaches used to screen for DVT, to understand approaches used to diagnose DVT and PE, and to understand national interest in a VTE research program in the ICU.

Methods

Instrument development

Items were generated for the instrument by examining original research and position papers on VTE. To address the five aforementioned objectives, items were clustered in five domains: decisional responsibility for VTE prophylaxis (inten-sivists, consultants, services, policies and guidelines), prophylaxis utilization (unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, pneumatic compression devices and thromboembolic stockings), approach to DVT screening (frequency, method, and patient subgroup), approach to VTE diagnosis (laboratory and imaging studies), and recommendations for further research on the prevention and diagnosis of VTE in critically ill patients. Respondents were asked to report current practice patterns in their ICU.

We used close-ended questions for the ICU demographic data to maximize the accuracy and completeness of responses [15]. Other responses were elicited using both open and close-ended questions. Diagnostic test utilization was recorded using five-point responses (1= never used, 2= rarely used, 3= sometimes used, 4= primarily used, and 5= always used). The instrument was pretested prior to administration for clarity of content and format.

Instrument administration

To select individuals with managerial responsibility and representative clinical experience, we surveyed ICU Directors in Canadian university affiliated hospitals running closed multi-disciplinary units. We used a self-administered rather than an interviewer-administered format to maximize the validity of self-reported information [16]. We contacted nonrespondents by facsimile with a second questionnaire [17], and then a telephone call. The survey was conducted from October to December 2000. Participation was voluntary and all responses were confidential.

Analysis

We report means and standard deviations, and proportions as appropriate. Chi square analysis was conducted to test for differences in the diagnostic approaches to both DVT and PE.

Results

Of 29 ICU Directors approached, 29 (100%) participated. Respondents represented 44 ICUs in Canada and 681 ICU beds (Table 1). ICUs were primarily mixed medical–surgical units (37/44, 84.1%) or exclusively surgical units (4/44, 9.1%), with a mean of 15.3 (9.9) beds per ICU.

VTE prophylaxis for critically ill patients is primarily determined by individual clinicians (20/29, 69.0%), with consultation from a hematology or thrombosis service for challenging patients in some centers (9/29, 31.0%). Decisions are made on a case-by-case basis (18/29, 62.1%), infrequently prompted by preprinted orders (5/29, 17.2%) or institutional policies (6/29, 20.7%), and rarely by a formal VTE prophylaxis practice guideline (2/29, 6.9%) (see http://www.critcare.lhsc.on.ca).

Unfractionated heparin (5000 U subcutaneously twice daily or three times daily) is universally reported to be predominant VTE prophylactic strategy (29/29, 100%). Low molecular weight heparin is used in many centers for orthopedic surgery patients (26/29, 89.7%), and in all ICUs that are regional trauma centers (18, 100.0%).

Use of pneumatic compression devices and thromboembolic stockings for VTE prophylaxis is presented in Table 2. Most reasons for utilizing nonpharmacologic approaches related to avoiding heparin exposure (e.g. current, recent or high risk of bleeding and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia) rather than to their perceived effectiveness at VTE prevention. Some ICU Directors reported never using pneumatic compression devices (11/29, 37.9%) or thromboembolic stockings (8/29, 27.6%). Combination VTE prophylaxis methods for postcar-diac surgery patients (e.g. unfractionated heparin with pneumatic compression devices), and neurosurgery (e.g. low molecular weight heparin with thromboembolic stockings) were also described (data not shown). We did not elicit information on the rationale for combination prophylaxis with pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches.

Early detection of DVT using surveillance screening was reported in a minority of ICUs (7/29, 24.1%), for various populations, including neurosurgery (n = 3), trauma (n = 3), patients with prolonged immobility (n = 2), contraindications to heparin (n = 2), or calf DVT (n = 1). The only systematic screening method used is lower limb ultrasound once (n = 2) or twice (n = 5) weekly.

The most common diagnostic test for DVT used in Canadian ICUs is lower limb Doppler ultrasound, which is used significantly more often than either D dimer or venography (P < 0.0001) to detect DVT (Fig. 1). Doppler ultrasound is reportedly used always (15/29, 51.7%) or primarily (14/29, 48.3%) for DVT diagnosis, whereas venography is rarely (17/29, 58.6%) or never (4/29, 13.8%) used.

Figure 2 shows the tests used to diagnose PE. A spiral computed tomography (CT) chest scan is used significantly more often than any other test (P < 0.0001), reportedly used always (5/29, 17.2%) or primarily (16/29, 55.2%). Ventilation–perfusion scans are sometimes used (16/29, 55.2%), whereas pulmonary angiograms are used sometimes (13/29, 44.8%) or rarely (11/29, 37.9%). A wide variation in D dimer utilization is evident for diagnosing both DVT and PE in Cana-dian ICUs.

ICU Directors uniformly endorsed the need for further studies on VTE in critically ill patients. Topics to address included the test properties and risk:benefit ratio of noninvasive VTE investigations in the ICU setting, accurate profiling of both the thrombotic and bleeding risk among critically ill subgroups, and the most cost-effective methods of VTE prophylaxis in medical–surgical ICU patients.

Discussion

In this survey representing practice patterns in 44 Canadian ICUs, we found that unfractionated subcutaneous heparin was the dominant method for prophylaxis against VTE in medical–surgical ICU patients, consistent with one randomized trial showing benefit in this setting [12]. As supported by other randomized trials, low molecular weight heparin was used for VTE prevention for trauma [14] and orthopedic surgery [18] patients.

VTE prophylaxis with pneumatic compression devices and thromboembolic stockings was variable, sometimes reported in combination with pharmacologic prevention. For example, thromboembolic stockings and low molecular weight heparin were prescribed in some centers for neurosurgery patients, as suggested by a recent trial showing that nadroparin and thromboembolic stockings were more effective than stockings alone for this population [19]. Pneumatic compression devices were used in combination with unfractionated heparin for cardiac surgery patients; this combination was shown to be more effective than prophylaxis with heparin alone for DVT prevention in another trial [20].

The reference standards of venography and pulmonary angiography are seldom used in practice to diagnose DVT and PE. The prevailing diagnostic approach for DVT is ultra-sonography despite its unclear performance characteristics in this population, instead of more accurate venography with its attendant risks of patient transport and contrast dye-induced renal insufficiency. A range of tests is used to diagnose PE: Ddimer, spiral CT scans, and ventilation–perfusion scans. Difficulty in diagnosing PE is highlighted by the challenge of an accurate pretest probability in the ICU setting, compounded by uncertain properties of these tests in ventilated patients who have acute and chronic illnesses and abnormal chest radiographs. Respondents in the present survey reported that helical CT chest scanning was the most common diagnostic test for PE, perhaps partly because this imaging procedure can concomitantly rule in or out other diagnoses. Helical CT chest scans, however, have a sensitivity for PE ranging from 53 to 100% and a specificity ranging from 81 to 100% according to a recent systematic review [21].

D dimer tests are less useful diagnostically for VTE. Wells et al found that the rapid whole blood assay for D dimer has a sensitivity of 93% for proximal DVT, a sensitivity of 70% for calf DVT, and a specificity of 77% compared with a reference standard of impedance plethysmography [22]. Ginsberg et al determined that the rapid whole blood assay for D dimer has a sensitivity and a specificity for PE, as diagnosed by ventilation–perfusion scan, of 85 and 68%, respectively [23]. Five different quantitative latex agglutination tests for D dimer yielded sensitivities of 97–100% and specificities of 19–29% when compared with pulmonary angiogram for the diagnosis of PE [24]. Applying the foregoing test properties of D dimer generated outside the ICU setting to critically ill patients may be further compromised by activation of the coagulation and inflammatory cascades in many critically ill patients for myriad reasons [25,26].

We hypothesize that the modest amount of research on VTE in the critically ill creates some uncertainty about best practice. The variation we identified in the present study with respect to nonpharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and the diagnostic approach to PE may be related to insufficient studies in critically ill patients. Additional factors explaining practice variation may include different interpretations of the merits of various tests and prophylactic methods, unique characteristics of each ICU population, and the influences of practice setting such as test availability. When several high quality studies generate consistent results and when there are few barriers to implementation such as risk and cost, we found that practice patterns regarding ventilator circuit and secretion management were more standardized [27].

We used evidence from three randomized trials to conduct this survey, suggesting that a self-administered format yields more valid self-reports than interviewer-administered questionnaires [16], that closed-ended formats yield more complete and valid demographic data than open-ended formats [15], and that appending second questionnaires to reminders maximizes response rates [17]. Our response rate was high and our findings generalizable to teaching institutions across Canada. There are, however, several limitations to this study. First, ICU Directors may not be aware of all local decisions, although their responses are probably representative of care delivered in their center. This limitation underscores the universal caveat of all surveys, that stated practice may not reflect actual practice. Second, using this sampling frame limits our ability to detect individual clinician factors associated with practice patterns. Third, this study was not designed to examine health services factors associated with practice patterns such as ICU organizational characteristics. Finally, we did not evaluate VTE treatment strategies such as weight-based, nurse-managed heparin nomograms, which can shorten the time to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation compared with empiric dosing by physicians in critical illness [28]. Nevertheless, survey methods yield useful estimates of the prevalence and range of VTE prophylactic and diagnostic strategies currently employed. In addition, the information we obtained serves as a foundation on which to build future research programs.

Research agendas in critical care are traditionally generated through investigator-initiated projects, industry-initiated projects, or funding agency directives. An alternative approach to set intensive care research priorities in the United Kingdom and Ireland incorporated a survey, then nominal group techniques to estimate consensus, and then a second survey to validate the findings [29]. Of 37 research topics with the strongest support, 24 addressed organizational aspects of critical care and 13 involved clinical investigations or technology assessment. In the present self-administered survey, Canadian ICU Directors unanimously recommended the development of collaborative research on VTE in the critically ill. Raising the methodologic standards for diagnostic test research [30], particularly in pulmonary medicine [31] and VTE [32], could better inform clinical decisions and minimize the dissemination of nondiscriminating and unnecessary tests. Pressing investigations in this field include accurate risk profiling for both VTE and bleeding events in critically ill subgroups, establishing likelihood ratios associated with clinical, laboratory and radiographic diagnostic tests for VTE, and a cost-effective comparison of unfractionated versus low molecular weight heparin for medical–surgical ICU patients.

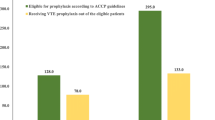

The 1986 National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference Report [33], the 1992 Thromboembolic Risk Factors Consensus Group [34], the 1998 ACCP Consensus Committee on Pulmonary Embolism [35], the 1998 Antithrombotic Consensus Conference [36], and the 1999 American Thoracic Society Practice Guideline on the Diagnosis of Venous Thromboembolism [37] do not mention medical–surgical critically ill patients. Observational studies show that VTE prophylaxis is prescribed in 33–86% of eligible patients at risk [9,38,39,40], suggesting insufficient attention to VTE prevention in the ICU. Recent editorials have proclaimed that clinicians 'must make their own decisions' regarding heparin prophylaxis for medical patients [41], and medical–surgical ICUs have been called 'the last frontier for prophylaxis' [42]. The geographical boundaries of the ICU make this venue highly suitable for conducting integrated research programs [43]. Canadian intensivists appear interested in addressing the many unanswered questions regarding VTE prevention and diagnosis in critically ill patients.

Appendix

Participating Canadian ICU Directors

Dr Gordon Wood (Victoria General Hospital, Royal Jubilee Hospital, Victoria), Dr Peter Dodek (St. Paul's Hospital, Vancouver), Dr John Fenwick (Vancouver Hospital & Health Sciences Centre, Vancouver), Dr Sean Keenan (Royal Columbian Hospital, New Westminster), Dr Richard Johnston (Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton), Dr Mark Heule (University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton), Dr Paul Boiteau (Foothills Medical Centre, Peter Lougheed Medical Center, Rockyview General Hospital, Calgary), Dr Jaime Pinilla (Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon), Dr Daniel Roberts (Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg), Dr Robert Light (St. Boniface Hospital, Winnipeg), Dr Frank Rutledge (London Health Sciences Centre – Victoria Site, London), Dr Michael Sharpe (London Health Sciences Centre – University Site, London), Dr Andreas Freitag (Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation – McMaster Site, Hamilton), Dr Allan McLellan (Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation – Henderson Site, Hamilton), Dr Brian Egier (Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation – General Site, Hamilton), Dr Peter Lovrics (St. Joseph's Hospital, Hamilton), Dr Thomas Stewart (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto), Dr David Mazer (St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto), Dr Patricia Murphy (Sunnybrook & Women's College Health Science Centres – Sunnybrook Site, Toronto), Dr John Marshall (Toronto Hospital – General Site and Western Site, Toronto), Dr Susan Moffatt (Kingston General Hospital, Kingston), Dr Richard Hodder (Ottawa Hospital – Civic Site, Ottawa), Dr Alan Baxter (Ottawa Hospital – General Site, Ottawa), Dr Donald Laporta (Jewish General Hospital, Montreal), Dr Peter Goldberg (CUSM – Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal), Dr Ashvini Gursahaney (CUSM – Montreal General Site, Montreal), Dr Yoanna Skrobik (Maissoneuve Rosemont Hospital, Montreal), Dr Harry Henteleff (Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax), and Dr Sharon Peters (Health Sciences Centre, St. Clare's Hospital, St. John's).

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

CT = computed tomography

- DVT:

-

DVT = deep venous thrombosis

- ICU:

-

ICU = intensive care unit

- PE:

-

PE = pulmonary embolism

- VTE:

-

VTE = venous thromboembolism.

References

Stein PD, Henry JW: Prevalence of acute pulmonary embolism among patients in a general hospital and at autopsy. Chest 1995, 108: 978-981.

Joynt GM, Kew J, Gomersall CD, Leung VYF, Liu EKH: Deep venous thrombosis caused by femoral venous catheters in critically ill adult patients. Chest 2000, 117: 178-183. 10.1378/chest.117.1.178

Attia J, Ray JG, Cook DJ, Douketis J, Ginsberg JS, Geerts W: Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in the critically ill. Arch Intern Med 2001, 161: 1268-1279. 10.1001/archinte.161.10.1268

Neuhaus A, Bentz RR, Weg JG: Pulmonary embolism in respiratory failure. Chest 1978, 73: 460-465.

Moser KM, LeMoine JR, Nachtwey FJ, Spragg RG: Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: Frequency in a respiratory intensive care unit. JAMA 1981, 246: 1422-1424. 10.1001/jama.246.13.1422

Saeger W, Genzkow M: Venous thromboses and pulmonary emboli in post-mortem series: Probable causes by correlations of clinical data and basic diseases. Pathol Res Pract 1994, 190: 394-399.

Schonhofer B, Kohler D: Prevalence of deep-venous thrombosis of the leg in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration 1998, 65: 173-177. 10.1159/000029254

Harris LM, Curl GR, Booth FV, Hassett JM Jr, Leney G, Ricotta JJ: Screening for asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in surgical intensive care patients. J Vasc Surg 1997, 26: 764-769.

Hirsch DR, Ingenito EP, Goldhaber SZ: Prevalence of deep venous thrombosis among patients in medical intensive care. JAMA 1995, 274: 335-337. 10.1001/jama.274.4.335

Marik PE, Andrews L, Maini B: The incidence of deep venous thrombosis in ICU patients. Chest 1997, 111: 661-664.

Geerts WH, Code KI, Jay RM, Chen E, Szalai JP: A prospective study of venous thromboembolism after major trauma. N Engl J Med 1994, 331: 1601-1606. 10.1056/NEJM199412153312401

Cade JF: High risk of the critically ill for venous thromboembolism. Crit Care Med 1982, 10: 448-450.

Fraisse F, Holzapfel L, Couland JM, Simonneau G, Bedock B, Feissel M, Herbecq P, Pordes R, Poussel JF, Roux L, and the Association of Non-University Affiliated Intensive Care Specialist Physicians of France: Nadroparin in the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in acute decompensated COPD. Am Rev Resp Crit Care Med 2000, 161: 1109-1114.

Geerts WH, Jay RM, Code KI, Chen E, Szalai JP, Sibil EA, Hamilton PA: A comparison of low-dose heparin with low-molecular-weight heparin as prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism after major trauma. N Engl J Med 1996, 335: 701-707. 10.1056/NEJM199609053351003

Griffith LE, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Charles C: Comparison of open versus closed questionnaire formats in obtaining demographic information from Canadian general internists. J Clin Epidemiol 1999, 52: 997-1005. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00106-7

Cook DJ, Guyatt Gh, Juniper E, Griffith L, McIlroy W, Willan A, Jaeschke R, Epstein R: Interviewer versus self-administered questionnaires in developing a disease-specific, health related quality of life instrument for asthma. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46: 529-534.

Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA: Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 1997, 50: 1129-1136. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00126-1

Palmer AJ, Koppenhagen K, Kirchhof B, Weber U, Bergemann R: Efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin, unfrac-tionate heparin and warfarin for thromboembolism prophylaxis in orthopedic surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Haemostasis 1997, 27: 75-84.

Nurmohamed MT, van Riel AM, Henkens CM, Koopman MM, Que GT, d'Azemar P, Buller HR, ten Cate JW, Hoek JA, van der Meer J, van der Heul C, Turpie AG, Haley S, Sicurella A, Gent M: Low molecular weight heparin and compression stockings in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in neurosurgery. Thromb Hemost 1996, 75: 233-238.

Ramos R, Salem BI, De Pawlikowski MP, Coordes C, Eisenberg S, Leidenfrost R: The efficacy of pneumatic compression stockings in the prevention of pulmonary embolism after cardiac surgery. Chest 1996, 109: 82-85.

Rathburn SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL: Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2000, 132: 227-232.

Wells PS, Brill-Edwards P, Stevens P, Panju A, Patel A, Douketis J, Massicotte P, Hirsh J, Weitz JI, Kearon C, Ginsberg JS: A novel and rapid whole-blood assay for D dimer in patients with clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis. Circulation 1995, 91: 2184-2187.

Ginsberg JS, Wells PS, Kearon C, Anderson D, Crowther M, Weitz JI, Bormanis J, Brill-Edwards P, Turpie AG, MacKinnon B, Gent M, Hirsh J: Sensitivity and specificity of a rapid whole-blood assay for D dimer in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med 1998, 129: 1006-1011.

Quinn DA, Fogel RB, Smith CD, Laposata M, Thompson BT, Johnson SM, Waltman AC, Hales CA: D dimers in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 1999, 159: 1445-1449.

Boldt J, Papsdorf M, Rothe A, Kumle B, Piper S: Changes of the hemostatic network in critically ill patients – is there a difference between sepsis, trauma and neurosurgery? Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 445-450. 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00026

Dhainaut JF: Introduction to the Margaux Conference on Critical Illness: Activation of the coagulation system in critical illness. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: S1-S3. 10.1097/00003246-200009001-00001

Cook DJ, Richard JD, Reeve BK, Randall J, Wigg M, Dreyfuss D, Brochard L: Ventilator circuit and secretion management strategies: A Franco-Canadian survey. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 3547-3554. 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00034

Brown G, Dodek P: An evaluation of empiric vs. nomogram-based dosing of heparin in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1997, 25: 1534-1538. 10.1097/00003246-199709000-00021

Vella K, Goldfrad C, Rowan K, Bion J, Black N: Use of consensus development to establish national research priorities in critical care. BMJ 2000, 320: 976-980. 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.976

Carrington M, Lachs MS, Feinstein AR: Use of methodologic standards in diagnostic test research. JAMA 1995, 274: 645-651.

Heffner JE, Feinstein D, Barbieri C: Methodologic standards for diagnostic test research in pulmonary medicine. Chest 1998, 114: 877-885.

Bates SM, Ginsberg JS, Straus S, Rekers H, Sackett DL: Criteria for evaluating evidence that laboratory abnormalities are associated with the development of venous thromboembolism. Can Med Assoc J 2000, 163: 1016-1021.

NIH Consensus Conference Report: Prevention of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. JAMA 1986, 256: 744-749.

Thromboembolic Risk Factors (THRIFT) Consensus Group: Risk and prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospital patients. BMJ 1992, 305: 567-574.

ACCP Consensus Committee on Pulmonary Embolism: Opinions regarding the diagnosis and management of venous throm-boembolic disease. Chest 1998, 113: 499-504.

Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Geerts W, Heit JA, Knudson M, Lieberman JR, Merli GJ, Wheeler HB: Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 1998, 114(suppl): 531S-560S.

American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline: The diagnostic approach to acute venous thromboembolism. Am Rev Resp Crit Care Med 1999, 160: 1043-1066.

Keane MG, Ingenito EP, Goldhaber SZ: Utilization of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the medical intensive care unit. Chest 1994, 106: 13-22.

Ryskamp RP, Trottier SJ: Utilization of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a medical–surgical ICU. Chest 1998, 113: 162-164.

Cook DJ, Attia J, Weaver B, McDonald E, Meade M, Crowther M: Venous thromboembolic disease: An observational study in medical–surgical ICU patients. J Crit Care 2000, 15: 127-132. 10.1053/jcrc.2000.19224

Lederle FA: Heparin prophylaxis for medical patients? Ann Intern Med 1998, 128: 768-770.

Goldhaber SZ: Venous thromboembolism in the intensive care unit: The last frontier for prophylaxis. Chest 1998, 113: 5-7.

Cook D, Heyland D, Marshall J: On the need for observational studies to design and interpret randomized trials in ICU patients: A case study in stress ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med 2001, 27: 347-354. 10.1007/s001340000828

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Project Manager Barbara Hill and the Canadian ICU Directors who participated in this survey (see Appendix). This study was funded by the Father Sean O'Sullivan Research Center, St. Joseph's Hospital, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. D Cook is an Investigator with the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cook, D., McMullin, J., Hodder, R. et al. Prevention and diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients: a Canadian survey. Crit Care 5, 336 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc1066

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc1066