Abstract

Background

There is a vast amount of information published regarding the impact of 2009 pandemic Influenza A (pH1N1) virus infection. However, a comparison of risk factors and outcome during the 2010-2011 post-pandemic period has not been described.

Methods

A prospective, observational, multi-center study was carried out to evaluate the clinical characteristics and demographics of patients with positive RT-PCR for H1N1 admitted to 148 Spanish intensive care units (ICUs). Data were obtained from the 2009 pandemic and compared to the 2010-2011 post-pandemic period.

Results

Nine hundred and ninety-seven patients with confirmed An/H1N1 infection were included. Six hundred and forty-eight patients affected by 2009 (pH1N1) virus infection and 349 patients affected by the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period were analyzed. Patients during the post-pandemic period were older, had more chronic comorbid conditions and presented with higher severity scores (Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA)) on ICU admission. Patients from the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period received empiric antiviral treatment less frequently and with delayed administration. Mortality was significantly higher in the post-pandemic period. Multivariate analysis confirmed that haematological disease, invasive mechanical ventilation and continuous renal replacement therapy were factors independently associated with worse outcome in the two periods. HIV was the only new variable independently associated with higher ICU mortality during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period.

Conclusion

Patients from the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period had an unexpectedly higher mortality rate and showed a trend towards affecting a more vulnerable population, in keeping with more typical seasonal viral infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a vast amount of information published regarding the impact of the 2009 pandemic Influenza A (H1N1)v infection [1, 2]. The pandemic represented a challenge for physicians worldwide, manifesting with the acute onset of respiratory failure in a patient population often young, with few comorbid conditions. Several recommendations have been considered, taking into account the literature published during this time. The early use of oseltamivir showed a survival benefit [3, 4], while the use of systemic corticosteroids did not [5, 6]. Identification of risk factors, such as the presence of community acquired respiratory co-infection (CARC) [7], obesity [8] and the development of acute kidney injury, have helped physicians gain a better understanding of the illness [9].

Health authorities warned that clinical suspicion should be maintained following the initial pandemic, with a post-pandemic period predicted for the 2010-2011 winter as a result of the former A/H1N1 2009 pandemic virus, currently called "new A/H1N1 virus" (An/H1N1) [10].

The aim of the present study was to compare risk factors, clinical features and outcomes in pandemic influenza An/H1N1 patients with those observed in the immediate post-pandemic influenza period.

Material and methods

This prospective, observational cohort study of intensive care unit (ICU) patients was conducted across 148 ICUs in Spain. Data were obtained from a voluntary registry created by the Spanish Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SEMICYUC), the Spanish Network for Research on Infectious Disease (REIPI) and the Spanish Biomedical Research Center Network on Respiratory Diseases (CIBERES). The study was approved by the Joan XXIII University Hospital Ethics Committee (IRB NEUMAGRIP/11809). Patient identification remained anonymous. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the observational nature of the study and the fact that this activity is an emergency public health response as reported elsewhere [11].

Data were reported by the attending physician after reviewing medical charts and radiological and laboratory records. Two periods were analyzed based on data on all patients within the cohort consecutively diagnosed with An/H1N1 influenza: the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period between epidemiological weeks 23 and 52 of 2009, and the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period between epidemiological weeks 50 and 52 of 2010 and weeks 1 to 9 of 2011. Children under 15 years old were not enrolled in the registry. The An/H1N1 infection was confirmed by means of real-time reverse-transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on either nasopharyngeal swab samples or tracheal secretions ordered by the attending physicians at intensive care unit (ICU) admission. An/H1N1 testing was performed in each institution or centralized in a reference laboratory when local resources were not available. RT-PCR methods and further details are described elsewhere [11]. A confirmed case was defined as an acute respiratory illness with laboratory-confirmed An/H1N1. Only confirmed cases were included in the current report.

The ICU admission criteria and treatment decisions for all patients, including determination of the need for intubation and type of antibiotic or antiviral therapy administered, were made at the discretion of the attending physician and not standardized. Septic shock and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (MODS) were defined following the criteria of the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of Critical Care Medicine [12].

Systemic corticosteroid use was implemented when patients developed shock (hydrocortisone), or coadjuvant treatment was used for pneumonia (methylprednisolone). Orally administered oseltamivir (150 mg/24 h or 300 mg/24 h) or intravenous zanamivir (600 mg/12 h) was chosen by the attending physician.

Primary viral pneumonia was defined where patients presented with acute respiratory distress, unequivocal alveolar opacities involving two or more lobes, and negative respiratory and blood bacterial cultures during the acute phase of influenza virus infection. Community-Acquired Respiratory Co-infection (CARC) was defined as any infection diagnosed within the first two days of hospitalization [7]. Infections occurring later were considered nosocomial. hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) was defined based on current American Thoracic Society and Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines [13]. Patients who presented with healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) were excluded from the present study [13]. Hematological disease was defined in those patients who presented with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, myeloma, graft versus host disease or post-bone marrow transplantation. Obese patients were defined as those with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m2[8]. Features such as smoking history and immunosuppressive factors were not recorded. Patients who had previously received Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent or seasonal influenza 2010-2011 vaccination were considered to be "vaccinated". Acute kidney injury (AKI) and its stages were diagnosed according to the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) criteria of the current Acute Kidney Injury Network definitions [14]. Diagnostic criteria for acute kidney injury (AKI): An abrupt (within 48 hours) reduction in kidney function currently defined as an absolute increase in serum creatinine of more than or equal to 0.3 mg/dl, a percentage increase in serum creatinine of more than or equal to 50% (1.5-fold from baseline), or a reduction in urine output (documented oliguria of less than 0.5 ml/kg per hour for more than six hours) [14]. Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) in the course of AKI was initiated when indicated for pulmonary edema, oliguria (defined as urine output <0.5 mL/kg body weight per hour for >6 h), metabolic acidosis or hyperkalaemia not responding to conventional treatment, or uraemia (defined as urea nitrogen of >100 mg/dL). CRRT was available 24 hours a day, and no patient requiring CRRT was denied treatment due to likely futility.

Statistical analysis

Discrete variables are expressed as counts (percentage) and continuous variables as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians with the 25th to 75th interquartile range (IQR). For the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients, differences between groups were assessed using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables when appropriate. Multivariable stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to assess the impact of explanatory variables in outcome (ICU mortality) for both the pandemic and post-pandemic periods. In order to avoid spurious associations, variables entered in the logistic regression models were those with a relationship in univariate analysis (P ≤0.1) or a potential plausible relationship with the outcome. To assess the possibility of a different impact of the explanatory variables in outcome for each period, interactions between explanatory variables and periods were used in the models. Results are presented as odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P-values. Data analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

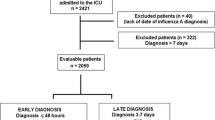

Nine hundred and ninety-seven patients with completed outcomes admitted to ICU with confirmed Influenza (H1N1)v infection were analyzed in this study. Of these, 648 patients were affected during the 2009 pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period and 349 patients during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period.

Patients from the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period were older, more frequently male and presented with more comorbidities than those affected by the 2009 pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection. Comorbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic renal disease and hematological disease. Pandemic and post-pandemic age-specific influenza ICU admission baseline characteristics are displayed in Figure 1. Vaccination was only available in Spain during the post-pandemic period. A total of 19 (5.4%) received vaccination. Vaccination was more frequent in patients who presented with comorbidities than those who did not (18 (7.0%) vs. 1 (1.1%), P = 0.02). There was no difference in time to diagnosis between vaccinated and non-vaccinated patient groups (6 IQR (4 to 8) vs. 8 IQR (5 to 11), P = 0.1. No particular comorbid condition was predominant in those vaccinated. Additional demographic data and clinical characteristics regarding delay in diagnosis and vaccination status are displayed in Table 1.

Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were higher in post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection patients. In addition, this cohort of patients was admitted later to the hospital from time of symptom onset (4.2 +/- 2.6 vs. 4.8 +/- 3.4, P = 0.004) and had a longer delay from time of hospitalization to diagnosis (2.3 +/- 2.1 vs.6.5 +/- 3.8, P <0.001). Primary viral pneumonia was documented in 688 (69.0%) patients with no significant difference between the two periods. In 176 (17.7%) cases another pathogen was isolated at ICU admission and these patients were considered to have CARC.

Empiric antibiotic therapy was administered in all patients in accordance with local protocols. Post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection patients received empiric antiviral treatment less frequently (99.1% vs. 97.4%, P = 0.04), lower doses of oseltamivir (150 mg/day) (73.5% vs. 51.5%, P <0.001), delayed antiviral administration (5.6 +/- 3.5 vs. 4.7 +/- 2.9 days, P <0.001), and had higher use of zanamivir (7.2% vs. 0.6%, P <0.001) than those from the 2009 pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period.

Comparison of complications during ICU stay was different between the two periods. Septic shock was present more frequently in the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period (54.4% vs. 45.4%, P = 0.007). Patients affected during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period received mechanical ventilation (invasive or non-invasive) more frequently (80.8% vs. 71.8%, P = 0.002); however, there was no significant difference in implementation of invasive mechanical ventilation. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (n = 9) was more frequently implemented during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period (1.7% vs. 0.5%, P = 0.07). AKI was more frequently identified during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period (27.2% vs. 20.1%, P = 0.01) with the use of CRRT significantly different between the two periods. Further details are displayed in Table 2.

In total, 246 (24.7%) patients died. No statistical difference in survival was observed between patient groups with respect to vaccination status (6 (5.7%) vs. 13 (5.3%), P = 0.8). The median age for non-survivors was significantly higher in the post-pandemic period (42 years (54 to 61.5) vs. 36 years (IQR 47 to 61), P <0.001)). Mortality was significantly higher in the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period compared to the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period (105 (30.1%) vs. 141(21.8%) OR 1.5 (95% CI 1.1 to 2.1)). The baseline characteristics of patients in both groups who did not survive are compared in Table 3. Briefly, during the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period, APACHE II score, SOFA score, age, congestive heart failure, chronic renal disease, hematological disease, CARC, septic shock, MODS, invasive mechanical ventilation (MV) and CRRT were variables associated with ICU mortality (univariate analysis). APACHE II score, SOFA score, hematological disease, HIV, CARC, septic shock, MODS, invasive MV and CRRT were associated variables during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period. Multivariate analysis (Table 4) confirmed that among patients in both groups the presence of hematological disease, the use of invasive MV, and CRRT were factors independently associated with a worse outcome. HIV was the only new variable independently associated with higher ICU mortality during the post-pandemic influenza (H1N1)v infection period. In addition, the only interaction statistically significant was between the presence of HIV and the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period.

Discussion

Data from this study evidenced that the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period targeted patients with a worse basal condition than those of the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period. Patients from the post-pandemic period were older, had more comorbidities, a more advanced clinical presentation on admission, higher severity scores, increased incidence of CARC and septic shock, and an increased requirement for mechanical ventilation than those from the pandemic period. In addition, patients from the post-pandemic period had a higher mortality rate.

Experiences during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period have demonstrated that the 2009 pandemic (H1N1) virus is still circulating and, importantly, still causing severe disease in younger people [10, 15–17]. During the immediate post-pandemic period multiple subtypes of influenza virus were analyzed in order to evaluate the isolation of other types of influenza viruses. The Ministry of Health reported that 98% of isolates were Influenza A (0.02% AH1; 0.08% AH1N1; 0.09 AH3; 0.33% AH3N2 and 99.5% 2009AH1N1), 1.4% Influenza B and 0.1% Influenza C [16].

Current World Health Organization (WHO) guidance strongly recommends the use of oseltamivir for severe or progressive infection with 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection, with zanamivir as an alternative if the infecting virus is oseltamivir-resistant [17]. Although the majority of 2009 pandemic (H1N1) viruses are susceptible to oseltamivir and very little resistance to oseltamivir has been found to date [18], the use of zanamivir has been 12 times more frequent during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period. Previous studies [3, 4] have shown that early oseltamivir administration resulted in increased survival among critically ill, ventilated patients and reduced complications in patients hospitalized during the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period. In addition, oseltamivir suppresses viral load more effectively when given early [19, 20]. It is important to recognize that the early control of viral load in patients may be explained by the actions of innate immunity followed by early anamnestic adaptive immune response [21]. The lack of an appropriate and early immune response because of innate humoral or cellular immunodeficiencies, concomitant use of immunosuppressors, or transient immunoparesis due to severe concomitant co-infection may predispose some patients to develop severe clinical progression [22]. The incidence of HIV was 2% and 3.7% during the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period and post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period respectively, but, interestingly, HIV was the only independent additional factor associated with higher ICU mortality in the post pandemic period. As previously reported, HIV patients, well controlled on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART), had a similar clinical outcome and prognosis to that of non-HIV patients during the pandemic period [23]]. However, in our study, HIV appeared to be a new independent risk factor for worse outcome. The immune response associated with severe viral infections remains unclear in HIV patients and needs to be further investigated, as the virus was no longer acting in a naive host.

While in 2009 the new virus found large numbers of people with no previous immunity against it, in 2010-2011 the situation dramatically changed. Large numbers of people had already received the vaccine, or alternatively had acquired natural immunity following infection by the time that the 2010-2011 season started. This created a more difficult environment for the virus to thrive, with a decreased percentage of susceptible individuals. It is plausible that with these changes in the population the virus would preferentially target hosts with chronic comorbidities, such as COPD, diabetes or HIV patients with altered cellular immunity. These conditions could potentially impair the efficiency of the immune response in clearing the infection. Proportional changes of the susceptible population could explain the observed differences in the profile of critically ill patients infected and the increased severity at admission to ICU. This trend is closer to the "normal" behaviour of seasonal influenza.

One important feature in both phases was the presence of acute respiratory failure as reflected by the need for invasive mechanical ventilation as an independent predictor of death. This finding is compatible with viral pneumonia being the principal cause of death in these patients and reinforces the role of the virus in causing critical illness. Despite the fact that non-invasive mechanical ventilation was not recommended for the management of patients affected by H1N1, its use was observed in 33% of cases in the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period. This finding may explain the delay in onset of invasive mechanical ventilation and a subsequently worse outcome during this period. It is important to recognise that the presence of neither CARC nor septic shock were independently associated with ICU mortality.

The presence of CARC has been a topic commonly discussed during previous pandemics [7]. A substantial base of laboratory evidence for synergism between Influenza A and bacterial microorganisms has been suggested [24]. During the 1918-1919 Influenza A pandemic, most deaths were attributed to concurrent bacterial infection [25]. Histopathological samples of lung tissue sections from fatal 1918 influenza case materials frequently revealed histopathologic findings consistent with acute bacterial pneumonia [26]. Nevertheless, this data result is surprising since CARC did not represent an independent risk factor for ICU mortality during either the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period or during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period. While many studies [27] have demonstrated temporal relationships between influenza activity and CARC, and also an increasing number of patients affected by CARC during the post-pandemic period, the present study did not show significant differences between the two periods.

During the first case reports of the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period, impairment of renal function was commonly observed and patients who died had documented multiple organ failure with significantly higher rates of renal failure [28]. AKI is a complex disorder that has been observed to occur in ICU patients with severe presentation of illness during the 2009 pandemic (H1N1)v infection period [29], and it has been associated with increased mortality rates. Interestingly, the rate of AKI was significantly higher during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period (27.2% vs. 20.1%, P <0.001) and, as has been reported previously [9], is associated with an increase in ICU mortality during the post-pandemic period. The cause-and-effect relationship between viral infection and kidney injury is not clear, nor is the reason for an increased incidence in the post-pandemic period. Glomerular deposition of viral antigen, cytokine dysregulation associated with severe viral infection, and virus-related rhabdomyolysis might partially explain the pathophysiology of AKI. However, there are several factors that might contribute to an increased incidence during the post-pandemic period. First, patients admitted in the post-pandemic period were older and presented with a higher severity of illness. Second, patients admitted in the post-pandemic period had a longer delay between diagnosis and onset for antiviral therapy. Finally, a higher incidence of septic shock might contribute to an increase in AKI. The reasons for and implications of AKI development in patients with H1N1 have not been clearly elucidated, and further research is needed in order to allow early identification of the subject at risk and provide targeted medical care.

The present study has some limitations that should be addressed. First, only adults admitted to Spanish ICUs were included and, therefore, our results might not be generalized to other countries or children. However, our study included more than 70% of all patients admitted to the ICU during the pandemic and post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection periods. Management of patients was not standardized and management practices were chosen in accordance with local protocols. Nevertheless, it has the strength of a prospective, multi-center design with a large number of patients. ECMO was rarely implemented in Spain (n = 9, 0.9%) and, therefore, no conclusions can be reached. Second, patients presenting in the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period had a delay in diagnosis, but time to diagnosis might be a non-objective parameter that depends on patient experience, the grade of physician and index of suspicion. Moreover, the unavailability of daily RT-PCR in some institutions during the post-pandemic period could prolong the time to diagnosis. Finally, the CD4 count was not recorded in HIV patients. Based on the epidemiological nature of the study only patients diagnosed with HIV were included in the group. It is important to note that some patients develop a low CD4 count when critically ill [30]. In addition, low CD4 cell counts, time since HIV diagnosis, HAART treatment or AIDS stage of disease; conversely, have not been identified as risk factors for ICU mortality in the post-HAART era [31]. Therefore, CD4 count in HIV patients should be further investigated. Finally, the marked change in time to diagnosis also suggests that there was laxity in testing during the present study. Cases may have been missed in the post-pandemic period with selection bias contributing to observed differences.

Conclusions

In summary, pandemics, like the viruses that cause them, are unpredictable. So was the immediate post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period. The main findings were that the mortality rate and severity scores were higher in the post-pandemic period. A lower clinical awareness and a more vulnerable population may explain the worse outcome in the post-pandemic period. The development of protocols, educational programs and prevention recommendations need to be implemented to avoid further diagnosis and treatment delays. As was previously warned [10], physicians should maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for future waves in order to prevent the unexpected increase in mortality observed in this study.

Key messages

-

The mortality rate and severity scores were higher in the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period.

-

During the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period, patients were older, with more comorbidities and with delayed hospital admission.

-

A more vulnerable population was affected in the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period.

-

HIV was the only new variable independently associated with higher ICU mortality during the post-pandemic Influenza (H1N1)v infection period.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

acute kidney injury

- AKIN:

-

Acute Kidney Injury Network: APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CAP:

-

community-acquired pneumonia

- CARC:

-

Community Acquired Respiratory Co-Infection

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CIBERES:

-

Spanish Biomedical Research Center Network on Respiratory Diseases

- CK:

-

creatinine kinase

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRRT:

-

continuous renal replacement therapy

- GFR:

-

glomerular filtration rate

- HAART:

-

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- HAP:

-

hospital-acquired pneumonia

- HCAP:

-

healthcare-associated pneumonia

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- MODS:

-

Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score

- MV:

-

mechanical ventilation

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- REIPI:

-

Spanish Network for Research on Infectious Disease

- RRT:

-

renal replacement therapy

- RT-PCR:

-

real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SEMICYUC:

-

Spanish Society of Intensive Care Medicine

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Perez-Padilla R, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S, Hernandez M, Quiñones-Falconi F, Bautista E, Ramirez-Venegas A, Rojas-Serrano J, Ormsby CE, Corrales A, Higuera A, Mondragon E, Cordova-Villalobos JA, INER Working Group on Influenza: Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2009, 361: 680-689. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904252

The ANZIC Influenza Investigators: Critical care services and 2009 H1N1 influenza in Australia and New Zealand. N Engl J Med 2009, 361: 1925-1934.

Rodríguez A, Díaz E, Martín-Loeches I, Sandiumenge A, Canadell L, Díaz JJ, Figueira JC, Marques A, Alvarez-Lerma F, Vallés J, Baladín B, García-López F, Suberviola B, Zaragoza R, Trefler S, Bonastre J, Blanquer J, Rello J, H1N1 SEMICYUC Working Group: Impact of early oseltamivir treatment on outcome in critically ill patients with 2009 pandemic influenza A. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011, 66: 1140-1149. 10.1093/jac/dkq511

Hiba V, Chowers M, Levi-Vinograd I, Rubinovitch B, Leibovici L, Paul M: Benefit of early treatment with oseltamivir in hospitalized patients with documented 2009 influenza A (H1N1): retrospective cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011, 66: 1150-1155. 10.1093/jac/dkr089

Martin-Loeches I, Lisboa T, Rhodes A, Moreno RP, Silva E, Sprung C, Chiche JD, Barahona D, Villabon M, Balasini C, Pearse RM, Matos R, Rello J, ESICM H1N1 Registry Contributors: Use of early corticosteroid therapy on ICU admission in patients affected by severe pandemic (H1N1)v influenza A infection. Intensive Care Med 2011, 37: 272-283. 10.1007/s00134-010-2078-z

Kim SH, Hong SB, Yun SC, Choi WI, Ahn JJ, Lee YJ, Lee HB, Lim CM, Koh Y, Korean Society of Critical Care Medicine H1N1 Collaborative: corticosteroid treatment in critically ill patients with pandemic Influenza A/H1N1 2009 Infection: analytic strategy using propensity scores. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 1207-1214. 10.1164/rccm.201101-0110OC

Martín-Loeches I, Sanchez-Corral A, Diaz E, Granada RM, Zaragoza R, Villavicencio C, Albaya A, Cerdá E, Catalán RM, Luque P, Paredes A, Navarrete I, Rello J, Rodríguez A, H1N1 SEMICYUC Working Group: Community-acquired respiratory co-infection (CARC)in critically ill patients infected with pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Chest 2011, 139: 555-562. 10.1378/chest.10-1396

Díaz E, Rodríguez A, Martin-Loeches I, Lorente L, del Mar Martín M, Pozo JC, Montejo JC, Estella A, Arenzana A, Rello J, H1N1 SEMICYUC Working Group: Impact of obesity in patients infected with new influenza A (H1N1)v. Chest 2011, 139: 382-386. 10.1378/chest.10-1160

Martin-Loeches I, Papiol E, Rodríguez A, Diaz E, Zaragoza R, Granada RM, Socias L, Bonastre J, Valverdú M, Pozo JC, Luque P, Juliá-Narvaéz JA, Cordero L, Albaya A, Serón D, Rello J, the H1N1 SEMICYUC Working Group: Acute kidney injury in critical ill patients affected by influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Crit Care 2011, 15: R66. 10.1186/cc10046

Influenza A(H1N1) 2009 virus: current situation and post-pandemic recommendations Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2011, 86: 61-65.

Rello J, Rodríguez A, Ibañez P, Socias L, Cebrian J, Marques A, Guerrero J, Ruiz-Santana S, Marquez E, Del Nogal-Saez F, Alvarez-Lerma F, Martínez S, Ferrer M, Avellanas M, Granada R, Maraví-Poma E, Albert P, Sierra R, Vidaur L, Ortiz P, Prieto del Portillo I, Galván B, León-Gil C, H1N1 SEMICYUC Working Group: Intensive care adult patients with severe respiratory failure caused by Influenza A (H1N1)v in Spain. Crit Care 2009, 13: R148. 10.1186/cc8044

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G, SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS 2001: SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: 1250-1256. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B

American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America: Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171: 388-416.

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A, Acute Kidney Injury Network: Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 2007, 11: R31. 10.1186/cc5713

Helferty M, Vachon J, Tarasuk J, Rodin R, Spika J, Pelletier L: Incidence of hospital admissions and severe outcomes during the first and second waves of pandemic (H1N1) 2009. CMAJ 2010, 182: 1981-1987. 10.1503/cmaj.100746

Sistema de Vigilancia de la Gripe en España[http://vgripe.isciii.es/gripe]

Smith JR, Ariano RE, Toovey S: The use of antiviral agents for the management of severe influenza. Crit Care Med 2010,38(4 Suppl):e43-51.

Hurt AC, Deng YM, Ernest J, Caldwell N, Leang L, Iannello P, Komadina N, Shaw R, Smith D, Dwyer DE, Tramontana AR, Lin RT, Freeman K, Kelso A, Barr IG: Oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses circulating during the first year of the influenza A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic in the Asia-Pacific region, March 2009 to March 2010. Euro Surveill 2011, 16: 19770.

Li IW, Hung IF, To KK, Chan KH, Wong SS, Chan JF, Cheng VC, Tsang OT, Lai ST, Lau YL, Yuen KY: The natural viral load profile of patients with pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) and the effect of oseltamivir treatment. Chest 2010, 137: 759-768. 10.1378/chest.09-3072

Ling LM, Chow AL, Lye DC, Tan AS, Krishnan P, Cui L, Win NN, Chan M, Lim PL, Lee CC, Leo YS: Effects of early oseltamivir therapy on viral shedding in 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2010, 50: 963-969. 10.1086/651083

Jegerlehner A, Schmitz N, Storni T, Bachmann MF: Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J Immunol 2004, 172: 5598-5605.

Cheng VC, Lau YK, Lee KL, Yiu KH, Chan KH, Ho PL, Yuen KY: Fatal co-infection with swine origin influenza virus A/H1N1 and community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . J Infect 2009, 59: 366-370. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.08.021

Riera M, Payeras A, Marcos MA, Viasus D, Farinas MC, Segura F, Torre-Cisneros J, Martín-Quirós A, Rodríguez-Baño J, Vila J, Cordero E, Carratalà J: Clinical presentation and prognosis of the 2009 H1N1 influenza A infection in HIV-1-infected patients: a Spanish multicenter study. AIDS 2010, 24: 2461-2467. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e508f

van der Sluijs KF, van der Poll T, Lutter R, Juffermans NP, Schultz MJ: Bench-to-bedside review: bacterial pneumonia with influenza - pathogenesis and clinical implications. Crit Care 2010, 14: 219. 10.1186/cc8893

Manuell ME, Co MD, Ellison RT: Pandemic influenza: implications for preparation and delivery of critical care services. J Intensive Care Med 2011, 26: 347-367. 10.1177/0885066610393314

Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS: Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis 2008, 198: 962-970. 10.1086/591708

Brundage JF: Interactions between influenza and bacterial respiratory pathogens: implications for pandemic preparedness. Lancet Infect Dis 2006, 6: 303-312. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70466-2

Bellomo R, Pettilä V, Webb SA, Bailey M, Howe B, Seppelt IM: Acute kidney injury and 2009 H1N1 influenza-related critical illness. Contrib Nephrol 2010, 165: 310-314.

Trimarchi H, Greloni G, Campolo-Girard V, Giannasi S, Pomeranz V, San-Roman E, Lombi F, Barcan L, Forrester M, Algranati S, Iriarte R, Rosa-Diez G: H1N1 infection and the kidney in critically ill patients. J Nephrol 2010, 23: 725-731.

Japiassú AM, Amâncio RT, Mesquita EC, Medeiros DM, Bernal HB, Nunes EP, Luz PM, Grinsztejn B, Bozza FA: Sepsis is a major determinant of outcome in critically ill HIV/AIDS patients. Crit Care 2010, 14: R152. 10.1186/cc9221

Vincent B, Timsit JF, Auburtin M, Schortgen F, Bouadma L, Wolff M, Regnier B: Characteristics and outcomes of HIV-infected patients in the ICU: impact of the highly active antiretroviral treatment era. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 859-866. 10.1007/s00134-004-2158-z

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Craig Dunlop for English language editing.

H1N1 SEMICYUC/REIPI/CIBERES Working Group investigators

Andalucía:

Pedro Cobo (Hospital Punta de Europa, Algeciras); Javier Martins (Hospital Santa Ana Motril, Granada); Cecilia Carbayo (Hospital Torrecardenas, Almería); Emilio Robles-Musso, Antonio Cárdenas, Javier Fierro (Hospital del Poniente, Almería); Dolores Ocaña Fernández (Hospital Huercal - Overa, Almería); Rafael Sierra (Hospital Puerta del Mar, Cádiz); Mª Jesús Huertos (Hospital Puerto Real, Cádiz); Juan Carlos Pozo, R. Guerrero (Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba); Enrique Márquez (Hospital Infanta Elena, Huelva); Manuel Rodríguez-Carvajal (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva); Ángel Estella (Hospital del SAS de Jerez, Jerez de la Frontera); José Pomares, José Luis Ballesteros (Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Granada); Yolanda Fernández, Francisco Lobato, José F. Prieto, José Albofedo-Sánchez (Hospital Costa del Sol, Marbella); Pilar Martínez; María Victoria de la Torre; María Nieto (Hospital Vírgen de la Victoria, Málaga); Miguel Angel Díaz Castellanos, (Hospital Santa Ana de Motril, Granada); Guillermo Sevilla, (Clínica Sagrado Corazón, Sevilla); José Garnacho-Montero, Rafael Hinojosa, Esteban Fernández, (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); Ana Loza, Cristóbal León (Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Valme, Sevilla); Angel Arenzana (Hospital Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla), Dolores Ocaña (Hospital de la Inmaculada, Sevilla), Inés Navarrete (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), Medhi Zaheri Beryanaki (Hospital de Antequera); Ignacio Sánchez (Hospital NISA Sevilla ALJARAFE, Sevilla)

Aragón:

Manuel Luis Avellanas, Arantxa Lander, S Garrido Ramírez de Arellano, MI Marquina Lacueva (Hospital San Jorge, Huesca); Pilar Luque; Elena Plumed Serrano; Juan Francisco Martín Lázaro (Hospital Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza); Ignacio González (Hospital Miquel Servet, Zaragoza); Jose Mª Montón (Hospital Obispo Polanco, Teruel); Paloma Dorado Regil (Hospital Royo Villanova, Zaragoza)

Asturias:

Lisardo Iglesias, Carmen Pascual González (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias - HUCA, Oviedo); Quiroga (Hospital De Cabueñes, Gijón); Águeda García-Rodríguez (Hospital Valle del Nalón, Langreo)

Baleares:

Lorenzo Socias, Pedro Ibánez, Marcío Borges-Sa; A. Socias, Del Castillo A (Hospital Son LLatzer, Palma de Mallorca); Ricard Jordà Marcos (Clínica Rotger, Palma de Mallorca); José M Bonell (USP. Clínica Palmaplanas, Palma de Mallorca); Ignacio Amestarán (Hospital Son Dureta, Palma de Mallorca)

Canarias:

Sergio Ruiz- Santana, Juan José Díaz, (Hospital Dr Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria); Sisón Juan (Hospital Doctor José Molina, Lanzarote); David Hernández, Ana Trujillo, Luis Regalado (Hospital General la Palma, La Palma); Leonardo Lorente (Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife); Mar Martín (Hospital de la Candelaria, Tenerife); Sergio Martínez, J. J. Cáceres (Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria)

Cantabria: Borja Suberviola, P. Ugarte (Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander)

Castilla La Mancha:

Fernando García-López, (Hospital General, Albacete); Angel Álvaro Alonso, Antonio Pasilla (Hospital General La Mancha Centro, Alcázar de San Juan); Mª Luisa Gómez Grande (Hospital General de Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real); Antonio Albaya (Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara, Guadalajara); Alfonso Canabal, Luis Marina (Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo); Almudena Simón (Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado, Toledo); José María Añón (Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Cuenca)

Castilla y León:

Juan B López Messa (Complejo Asistencial de Palencia, Palencia); Mª Jesús López Pueyo, Ortíz María del Valle (Hospital General Yagüe, Burgos); Zulema Ferreras (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca); Santiago Macias (Hospital General de Segovia, Segovia); José Ángel Berezo, Jesús;Blanco Varela (Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid), Andaluz Ojeda A (Hospital Universitario, Valladolid); Antonio Álvarez Terrero (Hospital Virgen de la Concha, Zamora); Fabiola Tena Ezpeleta (Hospital Santa Bárbara, Soria); Zulema Paez, Álvaro García (Hospital Virgen Vega, Salamanca)

Cataluña:

Rosa Mª Catalán ( Hospital General de Vic, Vic); Miquel Ferrer, Antoni Torres, Catia Cilloniz (Hospital Clínic, Barcelona); Sandra Barbadillo (Hospital General de Catalunya - CAPIO, Barcelona); Lluís Cabré, Ignacio Baeza (Hospital de Barcelona, Barcelona); Assumpta Rovira (Hospital General de l'Hospitalet, L'Hospitalet); Francisco Álvarez-Lerma, Antonia Vázquez, Joan Nolla (Hospital Del Mar, Barcelona); Francisco Fernández, Joaquim Ramón Cervelló; Raquel Iglesia (Centro Médico Delfos, Barcelona); Rafael Mañéz, J. Ballús, Rosa Mª Granada (Hospital de Bellvitge, Barcelona); Jordi Vallés, Marta Ortíz, C. Guía (Hospital de Sabadell, Sabadell); Fernando Arméstar, Joaquim Páez (Hospital Dos De Mayo, Barcelona); Jordi Almirall, Xavier Balanzo (Hospital de Mataró, Mataró); Jordi Rello, Elena Arnau, Marcos Pérez, César Laborda, Jesica Souto, Mercedes Palomar (Hospital Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona); Iñaki Catalán (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Manresa); Josep Mª Sirvent, Cristina Ferri, Nerea López de Arbina (Hospital Josep Trueta, Girona); Mariona Badía, Montserrat Valverdú- Vidal, Fernando Barcenilla (Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida); Mònica Magret (Hospital Sant Joan de Reus, Reus); MF Esteban, José Luna (Hospital Verge de la Cinta, Tortosa); Juan Mª Nava, J González de Molina (Hospital Universitario Mutua de Terrassa, Terrassa); Zoran Josic (Hospital de Igualada, Igualada); Francisco Gurri, Paula Rodríguez (Hospital Quirón, Barcelona); Alejandro Rodríguez, Thiago Lisboa, Ángel Pobo, Sandra Trefler (Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII, Tarragona); Rosa María Díaz (Hospital San Camil. Sant Pere de Ribes, Barcelona); Eduard Mesalles (Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona); Diego de Mendoza (Hospital M. Broggi, Sant Joan Despí)

Extremadura:

Juliá-Narváez José (Hospital Infanta Cristina, Badajóz); Alberto Fernández-Zapata, Teresa Recio, Abilio Arrascaeta, Mª José García-Ramos, Elena Gallego (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres); Fernándo Bueno (Hospital Virgen del Puerto, Plasencia); Mercedes Díaz (Hospital de Mérida, Mérida)

Galicia:

Mª Lourdes Cordero, José A. Pastor, Luis Álvarez - Rocha (CHUAC, A Coruña); Dolores Vila, (Hospital Do Meixoeiro, Vigo); Ana Díaz Lamas (Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, Ferrol); Javier Blanco Pérez, M Ortiz Piquer, (Hospital Xeral - Calde, Lugo); Eleuterio Merayo, Victor Jose López-Ciudad, Juan Cortes Cañones, Eva Vilaboy, José Villar Chao (Complejo Hospitalario de Ourense, Ourense); Eva Maria Saborido, (Hospital Montecelo, Pontevedra); Raul José González, (H. Miguel Domínguez, Pontevedra); Santiago Freita, Enrique Alemparte; Ana Ortega (Complejo Hospitalario de Pontevedra, Pontevedra); Ana María López; Julio Canabal, Enrique Ferres (Clinica Universitaria Santiago de Compostela, Santiago)

La Rioja:

José Luis Monzón, Félix Goñi (Hospital San Pedro, Logroño).

Madrid:

Frutos Del Nogal Sáez, M Blasco Navalpotro (Hospital Severo Ochoa, Madrid); Mª Carmen García-Torrejón, (Hospital Infanta Elena, Madrid); César Pérez-Calvo, Diego López (Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid); Luis Arnaiz, S. Sánchez- Alonso, Carlos Velayos (Hospital Fuenlabrada, Madrid); Francisco del Río, Miguel Ángel González (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid); María Cruz Martín, José Mª Molina (Hospital Nuestra Señora de América, Madrid); Juan Carlos Montejo, Mercedes Catalán (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid); Patricia Albert, Ana de Pablo (Hospital del Sureste, Arganda del Rey); José Eugenio Guerrero, María Zurita, Jaime Benitez Peyrat (Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid); Enrique Cerdá, Manuel Alvarez, Carlos Pey, (Hospital Infanta Cristina, Madrid); Montse Rodríguez, Eduardo Palencia (Hospital Infanta Leonor, Madrid); Rafael Caballero (Hospital de San Rafael, Madrid); Concepción Vaquero, Francisco Mariscal, S. García (Hospital Infanta Sofía, Madrid); Nieves Carrasco (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid); Isidro Prieto, A Liétor, R. Ramos (Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid); Beatríz Galván, Juan C. Figueira, M. Cruz Soriano (Hospital La Paz, Madrid); P Galdós, Bárbara Balandin Moreno (Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid); Fernández del Cabo (Hospital Monte Príncipe, Madrid); Cecilia Hermosa, Federico Gordo (Hospital de Henares, Madrid); Alejandro Algora (Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid); Amparo Paredes (Hospital Sur de Alcorcón, Madrid); JA Cambronero (Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Madrid); Sonia Gómez-Rosado, (Hospital de Móstoles, Madrid); Luis Miguel Prado López (Hospital Sanitas La Zarzuela, Madrid); Esteban A, Lorente JA, Nin N (Hospital de Getafe, Madrid)

Murcia:

Sofía Martínez (Hospital Santa María del Rosell, Murcia); F. Felices Abad, (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia); Mariano Martínez (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia); Sergio Manuel Butí, Bernardo Gil Rueda, Francisco García (Hospital Morales Messeguer, Murcia)

Navarra:

Laura Macaya, Enrique Maraví-Poma, I Jimenez Urra, L Macaya Redin, A Tellería (Hospital Virgen del Camino, Pamplona); Josu Insansti (Hospital de Navarra, Pamplona)

País Vasco:

Nagore González, Pilar Marco, Loreto Vidaur (Hospital de Donostia, San Sebastián); B. Santamaría, Tomás Rodríguez (Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao); Juan Carlos Vergara, Jose Ramon Iruretagoyena Amiano (Hospital de Cruces, Bilbao); Alberto Manzano, (Hospital Santiago Apóstol, Vitoria); Carlos Castillo Arenal (Hospital Txagorritxu, Vitoria); Pedro María Olaechea, Higinio Martín (Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Vizcaya)

Andorra:

Antoni Ribas (Hospital Nuestra Señora de Meritxell, Andorra)

Valencia:

José Blanquer (Hospital Clinic Universitari, Valencia); Roberto Reig Valero, A. Belenger, Susana Altaba (Hospital General de Castellón, Castellón); Bernabé Álvarez -Sánchez (Hospital General de Alicante, Alicante); Santiago Alberto Picos (Hospital Torrevieja Salud, Alicante); Ángel Sánchez-Miralles, (Hospital San Juan, Alicante); Juan Bonastre, M. Palamo, Javier Cebrian, José Cuñat ( Hospital La Fe, Valencia); Belén Romero (Hospital de Manises, Valencia); Rafael Zaragoza, Constantino Tormo (Hospital Dr Peset, Valencia); Virgilio Paricio, (Hospital de Requena, Valencia); Asunción Marques, S. Sánchez-Morcillo, S. Tormo (Hospital de la Ribera, Valencia); J. Latour (H.G Universitario de Elche, Valencia); M Ángel García (Hospital de Sagunto, Castellón)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Authors' contributions

IML made a substantial contribution. AR and IML assisted in the design of the study, coordinated patient recruitment, analyzed and interpreted the data and assisted in writing the paper. LV, CL, RG, JI, JEG, JB, AA and IN made important contributions to the acquisition and analysis of data. AT and JFBM were involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. IML, AR, DS and ED made substantial contributions to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data and revised the final manuscript version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin-Loeches, I., Díaz, E., Vidaur, L. et al. Pandemic and post-pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) infection in critically ill patients. Crit Care 15, R286 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10573

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10573