Abstract

Introduction

Activated protein C (APC) induces release of microparticles (MP) from primary physiological cells, which are found in patients undergoing treatment with recombinant human APC (rhAPC) for severe sepsis. We hypothesised that APC on these circulating MPs activate endothelial protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) to induce anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties that can improve patient outcome.

Methods

This was an experimental study on clinical samples in an intensive care setting, and included patients with severe sepsis who fulfilled criteria for treatment with rhAPC. The number of CD13+ MPs from the patients were analysed to determine their origin. They were also quantified for endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) and APC expression. Clinical relevance of these MPs were ascertained by comparing survival between the group receiving rhAPC (n = 25) and a control group of untreated patients (n = 25). MPs were also incubated with endothelial cells to analyse apoptotic gene expression, cytoprotection and anti-inflammatory effects.

Results

rhAPC treatment induced a significant increase in circulating MP-associated EPCR by flow cytometry (P < 0.05) and by quantitative ELISA (P < 0.005). APC expression also showed significant increases (P < 0.05). Numerically, CD13+ MPs were higher in rhAPC-treated survivors versus non-survivors. However, the number of non-survivors was low and this was not significantly different. APC on MPs was demonstrated to induce anti-apoptotic and endothelial barrier effects through the activation of endothelial PAR1.

Conclusions

rhAPC treatment in patients with sepsis significantly increases circulating EPCR + MPs. These MPs were noted to express APC, which has specific anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects, with a non-significant correlative trend towards survival. This suggests that MPs could disseminate APC function and activate endothelial PAR1 at distal vascular sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The presence of circulating microparticles (MPs) in septic patients is well recognised [1, 2] and is inducible by thrombin [3], cytokines [4], lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [5] and collagen [6]. Derived from cell membrane shedding as a result of activation or apoptosis, circulating MPs constitute a marker of vascular and systemic disease [7]. Rearrangement of membrane phospholipids during MP release can result in increased phosphatidylserine availability with procoagulant activity. In patients with myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus, elevated MP levels correlate with increased thromboembolic risk [8, 9]. However, their functional role in the pathophysiology of sepsis remains unclear.

Elevated circulating MPs do not cause thrombosis in healthy individuals, principally due to the protective effects of the natural anticoagulant, activated protein C (APC) [10]. APC is an anticoagulant [11] with anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties [12]. These beneficial effects may be explained by its binding to the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) with cleavage of endothelial protease activated receptor 1 (PAR1) [13]. Although, the relative in vivo usefulness of these effects are not yet known, recombinant human APC (rhAPC) is currently used to treat patients with sepsis [14]. Its current use remains controversial because of reports of severe bleeding complications during rhAPC treatment [15] and a second phase 3 trial is ongoing (PROWESS Shock) [16].

We have previously demonstrated that APC can generate MPs in vitro from EPCR-expressing cells, which retain anticoagulant and PAR1-dependent anti-inflammatory properties [17]. In vivo demonstration of these APC-MP in septic patients during rhAPC infusion [18] led us to hypothesize that such circulating MPs may retain their anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective properties in these patients. An increased number of these MPs would thus translate into clinical benefits for the patient with severe sepsis.

Materials and methods

Circulating MP-associated EPCR

Circulating MPs were from patients diagnosed with severe sepsis (American College of Chest Physicians criteria) [19], who also fulfilled the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (England and Wales) criteria [20] for rhAPC (Drotrecogin alfa (activated)) (Xigris®, Eli Lilly, Houten, Netherlands) treatment. The type of organisms isolated included pneumococcus, enterococcus, enterobacter, coagulase-negative staphylococcus and staphylococcus aureus. Patients who received a 96-hour continuous infusion of rhAPC (24 μg/kg/hr) were contrasted with an equal number of patients who were eligible but not treated because of concerns over bleeding risks. These concerns included gastrointestinal bleeding within six weeks (2), platelets < 30 × 109/L (6), internal bleeding (3), intracranial pathology (1), chronic severe liver disease (4), recent major surgery (7) and trauma (2). None of these patients were on heparin prophylaxis because of bleeding concerns and all rhAPC-treated patients received low molecular weight heparin prophylaxis before and after but not during rhAPC infusion. The study protocol was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee and the Research and Development departments of the Royal Liverpool University Hospital and Guy's and St. Thomas' Hospitals. Informed consent was obtained from patients or when patients were unable to consent, assent was sought from their next-of-kin for enrolment into the study and publication of results. Written consent was also obtained from six healthy normal donors who provided blood samples for MP isolation. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal. Blood samples were collected into 0.105 M trisodium citrate with and without 0.1 M benzamidine. From each patient, this was six blood samples. In the rhAPC-treated group, this was before rhAPC initiation and then at 24, 48, 72 and 96 (during rhAPC infusion) and 120 hours (post-rhAPC treatment). In the non-rhAPC treated group, corresponding time points for blood sampling were also used.

CD13 (aminopeptidase N) is a trans-membrane protease present in endothelial cells and recognised as a marker for MPs arising from these cells. EPCR, the cellular receptor for protein C and activated protein C, is primarily localized on endothelial membrane and has been demonstrated to be expressed on endothelial MPs. Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [17], CD13 and EPCR were enumerated from a MP-specific gate based on size and calculated in relation to 3 μm latex (polystyrene) beads. MPs were isolated by initial centrifugation of plasma at 5,000 g for 10 minutes to remove cells, followed by further centrifugation of the supernatent at 18,000 g for 30 minutes twice at 4°C. EPCR and APC on MPs were measured by ELISA, as previously described [17]. In brief, MPs were captured by anti-EPCR-RCR2 and detected using chromogen S2366 or anti-EPCR RCR49-biotin for quantifying APC and EPCR, respectively. All assays were performed blinded to knowledge of rhAPC treatment or its timing. For experiments assessing functional effects, platelet-derived MPs were removed as these are not induced by APC [17] by first labelling with CD41 (platelet glycoprotein IIb)-phycoerythrin (PE) for 15 minutes and mixed with anti-PE magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bisley, Surrey, UK) for 20 minutes on ice. Wash-through was collected for CD41-negative MPs with negativity confirmed by FACS. Clinical data were collected, including baseline characteristics and outcome at 28 days.

Functional assays

In addition to the clinical studies of MP number, functional assays were also performed to assess the effect of rhAPC-expressing MPs on endothelial cell function. Details of reagents and methods used to determine endothelial gene expression are available in Additional file 1. As previously reported [21, 22], a 1.5-or greater fold-change in hybridization intensity was used to denote significant regulatory change in gene expression. The effect of MPs on endothelial permeability was analysed in a dual chamber system using Evans Blue-labelled bovine serum albumin (BSA) [23]. In brief, EAhy926 cells (endothelial cell line) were plated on 6.5 mm diameter Transwell polycarbonate membranes of 3 μm pore size (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). Upper and lower chambers were filled with 100 μL and 500 μL of growth medium, respectively. Cells were grown for two days to obtain monolayers that were "sub-confluent". As described by Feistritzer [23], the sub-confluent model enables any improvement in endothelial barrier integrity to be detected; that is, reduction in leakiness by the agonist. Blocking antibodies and inhibitors were added 30 minutes before APC or MP. Cells were exposed to APC or MP for three hours and permeability assessed afterwards by adding 0.67 mg/ml Evans Blue in medium containing 4% BSA to the top chamber. After 10 minutes, an aliquot was taken from the lower chamber and diluted 1:2 in medium for measurement at 650 nm. Further studies on the influence of zymogen protein C on APC binding to MPs [24] was based on the binding assay of Regan et al.[25] (Supplementary Materials and methods).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) of at least four independent experiments. For MP quantification in Figure 1A, B, data were expressed as the median with interquartile ranges (IQR). In data that were not normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction were used.

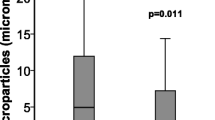

The clinical correlation of activated protein C-induced MPs with survival, EPCR expression and anticoagulant properties. Figure 1 shows the effect of rhAPC treatment on (A) CD13+ MPs, and (B) APC levels on MPs. MPs from 50 septic patients obtained on Day 1 (25 treated with rhAPC and 25 matching untreated non-rhAPC patients) were analysed by flow cytometry for CD13 positive MPs/ml of plasma. MPs were stained with PE IgG control or CD13 antibodies. Levels of APC on the MPs were quantified using S2366 by ELISA on MPs isolated from rhAPC-treated or non-treated patients. Survival at 28 days is denoted by + (n = 16 for both treated and untreated groups) and death by - (n = 9 for both groups). ** indicates significance of P ≤0.016 by Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. (C) Levels of EPCR expression were measured by ELISA on MPs isolated from plasma and the residual MP-free plasma from six rhAPC treated patients (light bars) and six matching untreated patients (dark bars) obtained on Day 0 and Day 1 (of rhAPC treatment or controlled time-point in non-rhAPC group). **P < 0.05 indicates significance difference between pre- vs. during-rhAPC as assessed by a Mann-Whitney U test. (D) APC activity on MP from six patients on Days 1 and 4 was estimated by the ability to generate thrombin after a prior Factor Va incubation step. The MPs were also incubated with Protein C antibody (PCAb) and α1-antitrypsin (α1AT) for assessing APC specificity, with APC plus phospholipid vesicles (APC + PCPS) as positive control and APC plus soluble endothelial protein C receptor (sEPCR) as negative control. The mean values ± SD are from duplicate samples in three experiments from each patient. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.005 indicates significant comparisons between Day 0 vs. Day 1, Day 0 vs. Day 4 in the absence and presence of PC antagonists.

Results

APC treatment in patients with sepsis induces the release of EPCR-expressing MPs

In initial experiments on six rhAPC treated patients, FACS demonstrated a significant increase in CD13 and EPCR expressing MPs (P < 0.05) within 24 hours of the treatment (Table 1). Due to sample volume limitations from the critically ill patients and concordant information from CD13 and EPCR expression in the available cases, further analyses (50 patients) utilised only CD13 positivity as a marker of EPCR-expressing MPs. Table 2 highlights the characteristics of these groups along with the APACHE II scores, sepsis aetiology, vasopressor treatment, DIC scores, ITU stay and survival data, which were comparable. A trend towards lower platelet counts was, however, noted in the non-rhAPC treated group.

Figure 1A shows that the number of CD13+ MPs was higher (P = 0.1) in patients that underwent rhAPC infusion and survived (22.7 × 106/ml, IQR 18.5 to 31.5) compared to rhAPC treated non-survivors (10 × 106/ml, IQR 8.2 to 28.9). The level of CD13+ MPs in the non-rhAPC treated survivor group were not significantly different statistically from non-rhAPC treated non-survivor patients (P = 0.19).

The amount of APC on the generated MPs was measured by ELISA (Figure 1B). The levels were significantly higher during rhAPC treatment compared with individual, pre-treatment controls and unrelated, non-rhAPC treated patient controls (Figure 1B). In all the 25 rhAPC-treated patients, the level of APC detected in MPs was between 120 and 350 ng/ml. Daily monitoring showed no significant variation in levels. Levels were higher from the rhAPC survivors (202.6 ng/ml, IQR 194.5 to 251.7) compared to the rhAPC treated non-survivors (187.5 ng/ml, IQR 160.2 to 198.4) (P = 0.04). These data were compared with our in vitro studies which showed that the proportion of rhAPC that is bound to MPs following APC stimulation is approximately 6 to 10% (Additional file 2). To assess if APC on MPs could be due to passive binding to already circulating MPs, rhAPC was added to plasma samples from non-rhAPC-treated septic patients for 24 hours. The results showed less than 20 ng/ml APC in these cases (data not shown), indicating that findings during rhAPC treatment reflect APC bound to circulating MP-associated EPCR. Specific EPCR ELISA indicated a significant increase of EPCR levels on MPs during rhAPC treatment (160 ng/ml) in comparison to pre-treatment levels (80 ng/ml) (Figure 1C). This was also demonstrated to be not because of passive binding of sEPCR to MPs, as sEPCR levels in MP-free plasma were unchanged from pre- to rhAPC-treatment samples.

MP-associated EPCR from APC-treated patients express anticoagulant activity

The functional aspects of MP released during rhAPC treatment were next analysed. Figure 1D shows a substantial loss in thrombin generation by these MPs compared with pre-treatment stage. Mean thrombin generation fell from approximately 294 ng/ml to 184 ng/ml during rhAPC infusion. This was reversible by PC blockade or the APC inhibitor, a1AT. By contrast, patients not treated with rhAPC did not express this anticoagulant property (data not shown). This indicates that a functionally active circulating form of APC exists on MP-EPCR during clinical treatment with rhAPC. APC levels on MPs were observed to be similar in the absence or presence of PC. This indicates that APC on patients' MPs (n = 4) are not easily displaceable as levels in the separated supernatant remained unchanged even at very high PC concentrations (Figure 2).

Effect of protein C (PC) on circulating activated protein C (APC)-induced microparticles (MPs). Levels of APC quantified by chromogenic S2366 on MPs isolated from patients (Day 2 of rhAPC treatment) compared to separated supernatant following 30 minutes of incubation with 0, 60 and 100 nM PC. Data represent mean values from four patients assayed in duplicate. **indicates P < 0.005 statistical significance comparing MPs to corresponding supernatant.

Circulating MP-associated EPCR affects APC-specific anti-apoptotic gene expression

Since APC on MP-EPCR in plasma retain anticoagulant activity, we postulated that they could modulate genes involved in apoptosis and inflammation. As the majority of circulating MPs are platelet-derived and platelets do not express EPCR [26], these were depleted to obtain an EPCR-enriched MP pool. The efficiency was 95 to 98% depletion and the vast majority of these CD41-depleted MPs were CD13 and EPCR positive (data not shown). When these MPs (approximately 0.15 × 106) were tested on gene arrays, those isolated during rhAPC treatment induced the expression of anti-apoptotic genes including A20, Bcl-x and the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2/kinase insert domain-containing receptor (KDR) (Figure 3). In most cases, PC blockade reversed these specific expressions (Additional file 3). Exceptions to the expression of several anti-apoptotic genes were matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, and MMP-1 to a lesser extent (PC blockade remained above the 1.5 cut-off level for significant regulatory change). Most transcript effects of APC were reversible by PAR1 antagonism with the exception of KDR. This could be because of PAR1-independent APC effects or insufficient PAR1 inhibition under these conditions.

Effect on the differential expression of selected genes by circulating microparticles bearing activated protein C. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were stimulated with microparticles (MPs) isolated from septic patients before (Day 0) and during (Day 1) recombinant human activated protein C (rhAPC) infusion compared to an equivalent concentration of free APC. Bax, Bcl-x, A20 and KDR genes were analysed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and expressed relative to untreated cells, which were set at 1. Data from six patients are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 denotes significant comparisons to untreated, with significant influences by protein C (PC) blockade or antagonist T1 denoted at base of chart.

APC on circulating microparticles prevents apoptosis via PAR1 activation

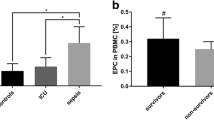

rhAPC-induced MPs could also inhibit apoptosis to a similar level as free-APC through a PAR-1 dependent mechanism (Figure 4). This cytoprotective property can be shown to be absent with PAR1 antagonism. Panel 8 (in Figure 4) shows that PC blockade did not, however, completely abrogate cytoprotective signals in all cells, suggesting that other cytoprotective mechanisms may exist in the context of rhAPC treatment. Another plausible explanation is that the MPs used were not 100% EPCR and APC positive. Nonetheless, these results indicate that circulating APC on MP-EPCR from rhAPC-treated patients have anti-apoptotic properties that are comparable to the free APC effect. Furthermore, this was not observed with MPs from non-rhAPC treated samples.

Effect of circulating microparticle-bound activated protein C (MP-APC) on an endothelial model of apoptosis. Light microscopy (X200 magnification) shows human umbilical vein endothelial cells: [1] untreated, and treated with [2] staurosporine (10 μM), [3] APC + staurosporine, [4] MPs from pre-rhAPC treatment (Day 0), [5] MPs from pre-rhAPC treatment + staurosporine, [6] MPs during rhAPC treatment (Day 4), [7] MPs during rhAPC treatment + staurosporine, [8] MPs during rhAPC treatment + Protein C (PC) Antibody (Ab) + staurosporine, and [9] MPs during rhAPC treatment + antagonist T1 + staurosporine. The bar chart shows corresponding release of up-taken dye with data from six separate experiments expressed as mean ± SD.*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.005 denote significant comparisons to untreated, with significant influences by PC blockade or T1 denoted at base of chart.

Barrier-protective effect of circulating APC-MP in a subconfluent endothelial model is APC and PAR1 dependent

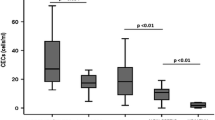

To further investigate a role for APC-MP on inflammation, the effect of free or MP-associated APC on endothelial permeability was examined. Using MPs from healthy donors as controls, we compared circulating APC-MP from three patients before and during rhAPC infusion. The same number of circulating MPs from healthy individuals or patients were applied; that is, 1.4 × 105 MPs per well. Figure 5 shows that circulating MPs from the rhAPC treatment period reduced permeability by approximately 35 to 40%, similar to free APC. This protective effect was again APC and PAR1 dependent. Notably, MPs taken from the patients before rhAPC treatment or those taken from healthy individuals had a minor protective effect that did not reach statistical significance. This was also neither APC- nor PAR1-dependent.

Effect of free and circulating microparticle-bound activated protein C on endothelial permeability. Endothelial cells seeded onto Transwell plates were incubated with 20 nmol/L free- activated protein C ( APC) or with 1.4 × 105 circulating microparticles (MP), for three hours and permeability was assessed using Evans-Blue-Bovine serum albumin. MP were obtained from Day 3 of rhAPC treatment. Specificity of APC and protease activated receptor 1 (PAR1) was investigated by inclusion of protein C (PCAb) antibody (10 μg/mL) or PAR1 specific antibody (ATAP2 at 20 μg/mL) for 30 minutes before incubation with APC or MPs. All experiments were performed as duplicates; n = 3. **P < 0.006 denote statistical significance in relation to untreated baseline; ♦♦ P < 0.006 denote significance between APC or, microparticle-associated APC (MP-APC) and blockade as assessed by a Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction.

Discussion

Our work is the first to demonstrate that APC can induce the generation and release of MPs in vitro and in vivo. A key finding from this study is that circulating MPs from patients during rhAPC treatment for severe sepsis possess APC-specific functional effects. The interaction between these MPs with endothelial cells can induce changes in gene expression, which translate into inhibiting apoptosis and reducing endothelial permeability. As these effects require PAR1 activation at the endothelial surface by APC in an EPCR-bound conformation [18], these results provide functional confirmation to earlier microscopy evidence of the assembled EPCR-APC complex on in vivo-derived MPs. Our findings also indicate that APC binding to EPCR within circulating MPs is stable and not displaceable by non-activated PC.

Whilst circulating MPs in sepsis and inflammatory conditions have been widely described, data on their function are limited. The majority highlight pro-inflammatory [27, 28], pro-apoptotic [29] and pro-coagulant [30, 31] potential of circulating MPs. Whilst increased MP levels in disease states are generally associated with adverse outcomes [32–34], Soriano reported that endothelial MP levels were higher in survivors of severe sepsis than in non-survivors [35]. Our findings would support this with rhAPC treatment significantly increasing endothelial-derived CD13+, EPCR+ MPs with a clinical correlative trend towards improved outcome. Expression of the functional EPCR-APC complex may be relevant to this trend in survival benefit as such MPs could bypass the requirement for cellular co-localisation of EPCR and PAR1 to induce APC anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective signaling [18]. As inflamed cell surfaces are EPCR deficient [36], MPs could be a vehicle for APC to act at a distance on PAR1 in other cells. This would reduce endothelial apoptosis and permeability in distal vascular sites, as supported by increases in anti-apoptotic A20 and Bcl-x with concomitantly reduced pro-apoptotic Bax. This would also reduce endothelial permeability as KDR up-regulation has barrier protective functions [18]. Our findings that APC-induced MPs are anticoagulant active suggest that these MPs might contribute to the bleeding risks associated with rhAPC treatment. No evidence of increased bleeding was, however, observed in the rhAPC-treated patient group.

Since thrombin can also cleave PAR1 to cause endothelial barrier disruption, the question as to how PAR1 mediates opposing effects has been debated and further clarified. Recently, APC-PAR1-dependent protection has been demonstrated in vivo in reversing inflammation-induced vascular leakage [37]. Such work in physiological systems, and also work in our own group [18], suggest that a key molecular differential is the APC-induced interaction between EPCR and sphingosine 1-phosphate that is important to cytoskeleton stability [38]. EPCR is co-localised with PAR1 in lipid rafts and APC facilitates their coupling to channel Gαi-PAR1 protective signalling [38]. Gαi-PAR1 recruitment also modifies the inner leaflet of plasma membranes and this may be mechanistically linked to MP formation [39]. With EPCR located within these glycosphingolipid-rich microdomains (rafts) and caveolae, this provides a likely pathway for calcium-regulated kinases and phosphatases, guanine nucleotide exchange factors and mitogen-activated protein kinase cassettes to form and release MP-EPCR [40]. As to thrombomodulin (TM) expression on APC-induced MPs, our investigations do not show a consistent presence (data not shown). This is not unexpected given that the cellular distribution of TM is different from EPCR [41] and MP generation by APC is EPCR-dependent but TM-independent.

A limitation of this study is in the numbers of rhAPC treated patients, especially with the relatively few deaths in the rhAPC treated group. To optimise the validity of our findings, we were careful to control for the rhAPC treated group with a group of patients who were equally eligible for rhAPC treatment but who were not treated due to clinician concern of bleeding risks. The platelet count in this group was significantly lower (Table 2) but should not have affected our MP findings or conclusions as platelets do not express EPCR. In addition, we have both inter- and intra-patient comparisons with sampling before and during rhAPC treatment. Through this and the comprehensive characterisation of both prognostic and functional aspects of circulating MPs, this study has taken a basic observational discovery along the translational pathway towards possible clinical relevance. It is important to note that our findings are limited to APC-induced MPs, which to our knowledge is not influenced by heparin or drugs that might have an endothelial effect. This is because the APC effect is specifically cell receptor-mediated, that is, via EPCR and PAR1. A limitation to clinical translation is that the data may not be applicable to the most seriously septic patients whose mortality is much higher than in the study patients.

Our findings are the first to highlight that there is an additional circulatory form of EPCR in human plasma, that is, MP-EPCR, which is different from soluble EPCR. Soluble EPCR is the cleaved, truncated form of EPCR (45kD) that cannot facilitate APC proteolytic anticoagulant activity [42]. Another novel finding is that this provides the first evidence in humans that the APC-PAR1 pathway is physiologically relevant because MP-EPCR release is dependent on PAR1 activation by APC [17]. Whilst the relative importance of free versus MP-associated APC remains to be clarified, free APC levels can be variable during treatment in patients with sepsis [43]. This may be due to stability and clearance factors or that cell-bound APC is not measured. Conversely, our findings that MP-associated APC are stable both in measurable levels and activities would point to physiological and clinical relevance as bioactive effectors in rhAPC-treated patients. This conclusion comes with the caveat that their clinical relevance requires further exploration, especially in larger numbers of patients with septic shock and higher mortality.

Conclusions

In conclusion, treatment of septic patients with APC can induce the release of MPs, which express EPCR. These MPs exhibit similar functional aspects to endothelium-associated EPCR by expressing anticoagulant activity, modulating APC-related anti-apoptotic gene expression and providing endothelial barrier protective effect through APC bound to them.

Key messages

-

rhAPC treatment in patients with sepsis significantly increases the number of circulating EPCR/CD13 expressing microparticles (MPs), with a clinical correlative trend towards improved outcome.

-

These MPs express APC, which has specific anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects.

-

This work suggests that MPs could disseminate APC function and activate endothelial PAR1 at distal vascular sites.

Abbreviations

- APC:

-

activated protein C

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- BSA:

-

bovine serum albumin

- DIC:

-

disseminated intravascular coagulation

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay

- EPCR:

-

endolthelial protein C receptor

- FACS:

-

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- ITU:

-

intensive treatment unit

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- KDR:

-

kinase insert domain-containing receptor

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

- MMP:

-

matrix metalloproteinase

- MPs:

-

microparticles

- PAR1:

-

protease activated receptor

- rhAPC:

-

recombinant activated protein C

- sEPCR:

-

soluble endolthelial protein C receptor

- TM:

-

thrombomodulin

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Mostefai HA, Meziani F, Mastronardi ML, Agouni A, Heymes C, Sargentini C, Asfar P, Martinez MC, Andriantsitohaina R: Circulating microparticles from patients with septic shock exert protective role in vascular function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008, 178: 1148-1155. 10.1164/rccm.200712-1835OC

Nieuwland R, Berckmans RJ, McGregor S, Boing AN, Romijn FP, Westendorp RG, Hack CE, Sturk A: Cellular origin and procoagulant properties of microparticles in meningococcal sepsis. Blood 2000, 95: 930-935.

Sapet C, Simoncini S, Loriod B, Puthier D, Sampol J, Nguyen C, Dignat-George F, Anfosso F: Thrombin-induced endothelial microparticle generation: identification of a novel pathway involving ROCK-II activation by caspase-2. Blood 2006, 108: 1868-1876. 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014175

Combes V, Simon AC, Grau GE, Arnoux D, Camoin L, Sabatier F, Mutin M, Sanmarco M, Sampol J, Dignat-George F: In vitro generation of endothelial microparticles and possible prothrombotic activity in patients with lupus anticoagulant. J Clin Invest 1999, 104: 93-102. 10.1172/JCI4985

Aras O, Shet A, Bach RR, Hysjulien JL, Slungaard A, Hebbel RP, Escolar G, Jilma B, Key NS: Induction of microparticle- and cell-associated intravascular tissue factor in human endotoxemia. Blood 2004, 103: 4545-4553. 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0713

Takano K, Asazuma N, Satoh K, Yatomi Y, Ozaki Y: Collagen-induced generation of platelet-derived microparticles in whole blood is dependent on ADP released from red blood cells and calcium ions. Platelets 2004, 15: 223-229. 10.1080/09537100410001682797

Freyssinet JM: Cellular microparticles: what are they bad or good for? J Thromb Haemost 2003, 1: 1655-1662. 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00309.x

Boulanger CM, Scoazec A, Ebrahimian T, Henry P, Mathieu E, Tedgui A, Mallat Z: Circulating microparticles from patients with myocardial infarction cause endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2001, 104: 2649-2652. 10.1161/hc4701.100516

Davi G, Ferroni P: Microparticles in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Thromb Haemost 2005, 3: 1166-1167. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01196.x

Berckmans RJ, Neiuwland R, Boing AN, Romijn FP, Hack CE, Sturk A: Cell-derived microparticles circulate in healthy humans and support low grade thrombin generation. Thromb Haemost 2001, 85: 639-646.

Hillarp A, Dahlback B, Zoller B: Activated protein C resistance: from phenotype to genotype and clinical practice. Blood Rev 1995, 9: 201-212. 10.1016/S0268-960X(95)90011-X

Joyce DE, Gelbert L, Ciaccia A, DeHoff B, Grinnell BW: Gene expression profile of antithrombotic protein c defines new mechanisms modulating inflammation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2001, 276: 11199-11203. 10.1074/jbc.C100017200

Mosnier LO, Griffin JH: Inhibition of staurosporine-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells by activated protein C requires protease-activated receptor-1 and endothelial cell protein C receptor. Biochem J 2003, 373: 65-70. 10.1042/BJ20030341

Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, LaRosa SP, Dhainaut JF, Lopez-Rodriguez A, Steingrub JS, Garber GE, Helterbrand JD, Ely EW, Fisher CJ Jr, Recombinant human protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study group: Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2001, 344: 699-709. 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001

Gentry CA, Gross KB, Sud B, Drevets DA: Adverse outcomes associated with the use of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in patients with severe sepsis and baseline bleeding precautions. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 19-25. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318192843b

Finfer S, Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, Dhainaut JF, Douglas IS, Gardlund B, Marshall JC, Rhodes A: Design, conduct, analysis and reporting of a multi-national placebo-controlled trial of activated protein C for persistent septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2008, 34: 1935-1947. 10.1007/s00134-008-1266-6

Perez-Casal M, Downey C, Fukudome K, Marx G, Toh CH: Activated protein C induces the release of microparticle-associated endothelial protein C receptor. Blood 2005, 105: 1515-1522. 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1896

Perez-Casal M, Downey C, Cutillas-Moreno B, Zuzel M, Fukudome K, Toh CH: Microparticle-associated endothelial protein C receptor and the induction of cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects. Haematologica 2009, 94: 387-394. 10.3324/haematol.13547

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ: Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 1992, 101: 1644-1655. 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence:Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for Severe Sepsis Technology Appraisal Guidance 84. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2004. [http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11546/32955/32955.pdf]

Schmidt U, Fuessel S, Haase M, Kraemer K, Meye A, Wirth MP: Quantification of C13orf19/P38IP mRNA expression by quantitative real-time PCR in patients with urological malignancies. Cancer Lett 2005, 225: 253-260. 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.037

Zheng J, Chen Y, Pat B, Dell'italia LA, Tillson M, Dillon AR, Powell PC, Shi K, Shah N, Denney T, Husain A, Dell'Italia LJ: Microarray identifies extensive downregulation of noncollagen extracellular matrix and profibrotic growth factor genes in chronic isolated mitral regurgitation in the dog. Circulation 2009, 119: 2086-2095. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.826230

Feistritzer C, Schuepbach RA, Mosnier LO, Bush LA, Di Cera E, Griffin JH, Riewald M: Protective signaling by activated protein C is mechanistically linked to protein C activation on endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2006, 281: 20077-20084. 10.1074/jbc.M600506200

Fukudome K, Esmon CT: Identification, cloning, and regulation of a novel endothelial cell protein C/activated protein C receptor. J Biol Chem 1994, 269: 26486-26491.

Regan LM, Mollica JS, Rezaie AR, Esmon CT: The interaction between the endothelial cell protein C receptor and protein C is dictated by the gamma-carboxyglutamic acid domain of protein C. J Biol Chem 1997, 272: 26279-26284. 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26279

Lynch SF, Ludlam CA: Plasma microparticles and vascular disorders. Br J Haematol 2007, 137: 36-48.

Ogura H, Kawasaki T, Tanaka H, Koh T, Tanaka R, Ozeki Y, Hosotsubo H, Kuwagata Y, Shimazu T, Sugimoto H: Activated platelets enhance microparticle formation and platelet-leukocyte interaction in severe trauma and sepsis. J Trauma 2001, 50: 801-809. 10.1097/00005373-200105000-00005

Fujimi S, Ogura H, Tanaka H, Koh T, Hosotsubo H, Nakamori Y, Kuwagata Y, Shimazu T, Sugimoto H: Activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes enhance production of leukocyte microparticles with increased adhesion molecules in patients with sepsis. J Trauma 2002, 52: 443-448. 10.1097/00005373-200203000-00005

Janiszewski M, Do Carmo AO, Pedro MA, Silva E, Knobel E, Laurindo FR: Platelet-derived exosomes of septic individuals possess proapoptotic NAD(P)H oxidase activity: A novel vascular redox pathway. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 818-825. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000114829.17746.19

Joop K, Berckmans RJ, Nieuwland R, Berkhout J, Romijn FP, Hack CE, Sturk A: Microparticles from patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and sepsis support coagulation through multiple mechanisms. Thromb Haemost 2001, 85: 810-820.

Watanabe J, Marathe GK, Neilsen PO, Weyrich AS, Harrison KA, Murphy RC, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM: Endotoxins stimulate neutrophil adhesion followed by synthesis and release of platelet-activating factor in microparticles. J Biol Chem 2003, 278: 33161-33168. 10.1074/jbc.M305321200

Agouni A, Lagrue-Lak-Hal AH, Ducluzeau PH, Mostefai HA, Draunet-Busson C, Leftheriotis G, Heymes C, Martinez MC, Andriantsitohaina R: Endothelial dysfunction caused by circulating microparticles from patients with metabolic syndrome. Am J Pathol 2008, 173: 1210-1219. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080228

Hron G, Kollars M, Weber H, Sagaster V, Quehenberger P, Eichinger S, Kyrle PA, Weltermann A: Tissue factor-positive microparticles: cellular origin and association with coagulation activation in patients with colorectal cancer. Thromb Haemost 2007, 97: 119-123.

Tesselaar ME, Romijn FP, Van Der Linden IK, Prins FA, Bertina RM, Osanto S: Microparticle-associated tissue factor activity: a link between cancer and thrombosis? J Thromb Haemost 2007, 5: 520-527. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02369.x

Soriano AO, Jy W, Chirinos JA, Valdivia MA, Velasquez HS, Jimenez JJ, Horstman LL, Kett DH, Schein RM, Ahn YS: Levels of endothelial and platelet microparticles and their interactions with leukocytes negatively correlate with organ dysfunction and predict mortality in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 2540-2546. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000186414.86162.03

Sesin CA, Yin X, Esmon CT, Buyon JP, Clancy RM: Shedding of endothelial protein C receptor contributes to vasculopathy and renal injury in lupus: in vivo and in vitro evidence. Kidney Int 2005, 68: 110-120. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00385.x

Niessen F, Furlan-Freguia C, Fernandez JA, Mosnier LO, Castellino FJ, Weiler H, Rosen H, Griffin JH, Ruf W: Endogenous EPCR/aPC-PAR1 signaling prevents inflammation-induced vascular leakage and lethality. Blood 2009, 113: 2859-2866. 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192385

Bae JS, Yang L, Manithody C, Rezaie AR: The ligand occupancy of endothelial protein C receptor switches the protease-activated receptor 1-dependent signaling specificity of thrombin from a permeability-enhancing to a barrier-protective response in endothelial cells. Blood 2007, 110: 3909-3916. 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096651

Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS: G-protein-coupled receptors and signaling networks: emerging paradigms. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2001, 22: 368-376. 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01678-3

van Gorp RM, Heeneman S, Broers JL, Bronnenberg NM, van Dam-Mieras MC, Heemskerk JW: Glutathione oxidation in calcium- and p38 MAPK-dependent membrane blebbing of endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1591: 129-138. 10.1016/S0167-4889(02)00273-2

Laszik Z, Mitro A, Taylor FB Jr, Ferrell G, Esmon CT: Human protein C receptor is present primarily on endothelium of large blood vessels: implications for the control of the protein C pathway. Circulation 1997, 96: 3633-3640.

Kurosawa S, Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Carson CW, D'Angelo A, Della Valle P, Esmon CT: Plasma levels of endothelial cell protein C receptor are elevated in patients with sepsis and systemic lupus erythematosus: lack of correlation with thrombomodulin suggests involvement of different pathological processes. Blood 1998, 91: 725-727.

Macias WL, Dhainaut JF, Yan SC, Helterbrand JD, Seger M, Johnson G, Small DS: Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in patients with severe sepsis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002, 72: 391-402. 10.1067/mcp.2002.128148

Toh CH, Hoots WK: The scoring system of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: a 5-year overview. J Thromb Haemost 2007, 5: 604-606. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02313.x

Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR: Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest 1973, 52: 2745-2756. 10.1172/JCI107470

Brazma A, Hingamp P, Quackenbush J, Sherlock G, Spellman P, Stoeckert C, Aach J, Ansorge W, Ball CA, Causton HC, Gaasterland T, Glenisson P, Holstege FC, Kim IF, Markowitz V, Matese JC, Parkinson H, Robinson A, Sarkans U, Schulze-Kremer S, Stewart J, Taylor R, Vilo J, Vingron M: Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat Genet 2001, 29: 365-371. 10.1038/ng1201-365

Liaw PC, Ferrell G, Esmon CT: A monoclonal antibody against activated protein C allows rapid detection of activated protein C in plasma and reveals a calcium ion-dependent epitope involved in factor Va inactivation. J Thromb Haemost 2003, 1: 662-670. 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00153.x

Liaw PC, Neuenschwander PF, Smirnov MD, Esmon CT: Mechanisms by which soluble endothelial cell protein C receptor modulates protein C and activated protein C function. J Biol Chem 2000, 275: 5447-5452. 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5447

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the patients, their relatives and the ICU staff. We also thank the Wellcome Trust (077950), Medical Research Council (G0501641), British Journal of Haematology/ISTH Grant, National Institute of Health Research and North West Development Agency for infrastructural and project support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MPC participated in the study design and coordination, carried out the molecular genetic studies and functional assays, and helped to draft the manuscript. VT carried out the MP number experiments and functional assays and helped to draft the manuscript. CD carried out the MP number experiments. IW and DW contributed patient samples. JT helped to draft the manuscript. CHT conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2011_9615_MOESM2_ESM.TIFF

Additional file 2:Supplementary Figure S1. The proportion of free versus bound rhAPC on microparticles. Comparison of results obtained from patient samples to in vitro derived MPs. (TIFF 31 KB)

13054_2011_9615_MOESM3_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 3:Supplementary table S1. Genes modulated by APC (free or microparticle [MP]-bound from patients). Microarray results. (DOCX 17 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Casal, M., Thompson, V., Downey, C. et al. The clinical and functional relevance of microparticles induced by activated protein C treatment in sepsis. Crit Care 15, R195 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10356

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10356