Abstract

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a frequent cause of ventilator-acquired pneumonia (VAP). Candida tracheobronchial colonization is associated with higher rates of VAP related to P. aeruginosa. This study was designed to investigate whether prior short term Candida albicans airway colonization modulates the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa in a murine model of pneumonia and to evaluate the effect of fungicidal drug caspofungin.

Methods

BALB/c mice received a single or a combined intratracheal administration of C. albicans (1 × 105 CFU/mouse) and P. aeruginosa (1 × 107 CFU/mouse) at time 0 (T0) upon C. albicans colonization, and Day 2. To evaluate the effect of antifungal therapy, mice received caspofungin intraperitoneally daily, either from T0 or from Day 1 post-colonization. After sacrifice at Day 4, lungs were analyzed for histological scoring, measurement of endothelial injury, and quantification of live P. aeruginosa and C. albicans. Blood samples were cultured for dissemination.

Results

A significant decrease in lung endothelial permeability, the amount of P. aeruginosa, and bronchiole inflammation was observed in case of prior C. albicans colonization. Mortality rate and bacterial dissemination were unchanged by prior C. albicans colonization. Caspofungin treatment from T0 (not from Day 1) increased their levels of endothelial permeability and lung P. aeruginosa load similarly to mice receiving P. aeruginosa alone.

Conclusions

P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury is reduced when preceded by short term C. albicans airway colonization. Antifungal drug caspofungin reverses that effect when used from T0 and not from Day 1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) occurs in a considerable proportion of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation and is associated with substantial morbidity, a two-fold increase in mortality rate, and excess cost [1]. Tracheobronchial colonization (TBC) and duration of mechanical ventilation are the two most important risk factors for VAP [2, 3]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most frequent causative microorganisms of VAP [2–4]. Several studies have reported the presence of Candida species in the airway specimens of immunocompetent ventilated patients [5, 6]. Candida TBC occurs in 17% to 28% of ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours [7–9]. Although the relationship between tracheal biofilm and VAP is based on one small observational study, P. aeruginosa is the most common pathogen retrieved from endotracheal tube biofilm in patients with VAP [10]. P. aeruginosa and C. albicans coexist predominantly as biofilms rather than as free-floating (planktonic) cells on abiotic medical devices (catheters and prostheses) [11, 12].

The question of their interplay has been addressed by several experimental and clinical studies. So far, in vitro studies suggest that the interaction between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa is likely to be antagonistic. When mixing in vitro cultures, P. aeruginosa is involved in killing C. albicans filaments associated with biofilm formation [13]. Additionally, quorum-sensing signaling molecules of P. aeruginosa impair C. albicans yeast-to-hyphae transition [14]. The relative C. albicans hyphal-binding affinity within biofilm is reported to be lower for P. aeruginosa than for Staphylococcus aureus [15]. In contrast, a synergistic relationship is described in vivo with a recent study showing that C. albicans TBC facilitates P. aeruginosa pneumonia occurrence in a rat model [16]. A recent clinical study suggested an interaction between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa [8]. The authors identified Candida spp. tracheobronchial colonization as an independent risk factor for P. aeruginosa pneumonia. No cause-and-effect relationship was demonstrated in that study. In addition, Candida spp. tracheobronchial colonization and P. aeruginosa pneumonia could both be a consequence of prior antibiotic treatment. Further, the median duration of mechanical ventilation in that study was 13 days. Therefore, the results could not be generalized to patients with shorter duration of mechanical ventilation. Another recent preliminary case-control study suggested that antifungal treatment might be associated with reduced risk for VAP or TBC related to P. aeruginosa [9], although no definite conclusion can be drawn from this observational retrospective single-center study including a small number of patients.

The study of P. aeruginosa and C. albicans interactions in the respiratory tract aims at more effectively understanding the balance between microbial ecology and bacteria-related pathogenesis. This issue has major environmental and medical consequences. The present study proposes to investigate P. aeruginosa-related lung injury in mice previously colonized with C. albicans and to evaluate the impact of caspofungin antifungal treatment.

Materials and methods

Animals

BALB/c mice (20 to 25 g) purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Domaine des Oncins, L'Arbresle, France) were housed in a pathogen-free unit of the Lille University Animal Care Facility and allowed food and water ad lib. All experiments were performed with the approval of the Lille Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Growth conditions for bacterial and yeast strains

The wild type strain Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 was grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C for 16 h and was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 minutes. The bacterial pellets were washed twice and diluted in an isotonic saline solution to obtain an optical density of 0.63 to 0.65 nm determined by spectrophotometry [17].

The reference strain C. albicans SC5314 was maintained at 4°C on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) [18]. For the study, cell of broth test isolates were grown in SDA at 37°C in a shaking incubator for 18 h.

Mice infection

Mice were infected by direct intratracheal inoculation under short anaesthesia with inhaled sevoflurane (Servorane™, Abbott, Queenborough, UK) as previously described [17]. For each mouse, 50 μl of fungal or bacterial suspension containing 2 × 106 or 2 × 107 or 2 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml of yeasts or 2 × 108 CFU/ml of bacteria respectively, was instilled. Control mice received 50 μl of sterile saline solution.

Treatment with caspofungin

Caspofungin (Merck & Co. Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) was injected intraperitoneally once daily either from T0 or from 24 h post-C. albicans challenge. The full recommended dose of 1 mg/kg was administered the first day of treatment and then 0.8 mg/kg was administrated on Days 2, 3, and 4.

Quantitative blood culture and pulmonary bacterial and fungal loads

For bacterial blood culture, 100 μl of blood was plated on bromocresol purple (BCP) agar plates for 24 h at 37°C to allow for P. aeruginosa growth. In co-infected groups, BCP agars were treated with 50 μg per plate of caspofungin. For fungal blood culture, the same amount was plated on yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) agar plates containing 1% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 2% D-glucose and 500 mg/l amikacin sulphate and incubated for 48 h at 37°C to allow for C. albicans growth.

For quantification of lung bacterial loads, lungs were removed after exsanguination via intracardiac puncture and homogenized in 0.9 ml of sterile isotonic saline solution. Viable bacteria were counted after serial dilutions of 100 μL of lung homogenate on BCP agar plates for 24 h at 37°C to allow for P. aeruginosa growth. Similarly, another 100 μL of lung homogenate was plated on YPD plates for 48 h to allow for C. albicans growth. In co-infected groups, agar was treated with caspofungin or amikacin.

In vivo quantification of acute lung injury: alveolar-capillary barrier permeability

125I-albumin was injected as a vascular protein tracer and its leakage across the endothelial barrier and accumulation in the extravascular spaces of the lungs was measured using a previously described permeability index [19]. More details are provided in the Additional file 1.

Determination of histological score

At Days 2 and 4, the lungs were removed and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde-acid and embedded in paraffin for histologic analysis. Cross-sections (3 μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain (Sigma-Aldrich Europe, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France) and periodic acid Schiff. Two independent blinded investigators graded the inflammation score. The degree of peribronchial and perivascular inflammation was evaluated on a subjective scale of 0 to 3, as described elsewhere [20].

Fluorescence staining of C. albicans in situ

Paraffin-embedded lung sections were stained with either the monoclonal antibody (mAb) 5B2 or the galenthus nivalis lectin [21, 22] and examined by immunofluorescence microscopy (Leica Microsystems AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland).

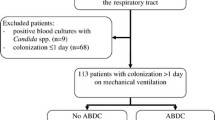

Experimental groups

Animals were randomly assigned to the following groups: Ca: mice infected with 1 × 105 CFU of C. albicans at T0 and sacrificed at Day 2 or 4; Pa: mice infected with 1 × 107 CFU of P. aeruginosa at Day 2 and sacrificed at Day 4; CaPa: mice infected with 1 × 105 CFU of C. albicans at T0, infected with 1 × 107 CFU of P. aeruginosa at Day 2 after infection by C. albicans, and sacrificed at Day 4; CaPaCasp0 and CaPaCasp1: mice infected with 1 × 105 CFU of C. albicans at T0, treated with caspofungin from T0 or from Day 1 to Day 4, infected with 1 × 107 CFU of P. aeruginosa at Day 2 after infection by C. albicans, and sacrificed at Day 4. The experimental design is further detailed in Table 1. The sample size was four (microbial count assay), five (mortality assay), and eight animals (permeability index assay) per group. Each experiment was performed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis

Mortality rates were compared between groups by using the log rank test with Kaplan-Meier analysis. Data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance test using Dunn's method to compare differences between groups (GraphPad Prism, v5.0, La Jolla, California, USA). Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

C. albicans tracheobronchial colonization in mice and dose-dependent pathophysiological effects

To set up the model of tracheobronchial colonization, mice were challenged with three doses of C. albicans (1 × 105, 1 × 106, and 1 × 107 CFU per mouse). At Day 2, mortality rates were 0%, 20%, and 100% respectively, indicating a dose-dependent effect of C. albicans. At Day 2, after a dose of 1 × 105 and 1 × 106 CFU per mouse, the amount of live C. albicans in lungs was diminished by 2.5 logs for both doses (Figure 1A) and none of them induced positive fungal blood cultures (data not shown). At that time, the lung endothelial permeability was similar in the control saline solution groups and the 1 × 105 CFU group (Figure 1B). On the contrary, the efflux of the protein tracer was statistically greater for the 1 × 106 CFU group than for the control saline solution groups (P < 0.01). Regarding lung histopathology, an increase of inflammatory cell infiltration within bronchiole and in the surrounding lung parenchyma was observed at Day 2 in the lung of mice receiving 1 × 105 C. albicans cells on the photomicrographs in comparison to control mouse lungs followed by full recovery at Day 4. Immunostained lung sections from mice challenged with C. albicans showed the presence of C. albicans blastoconidia (absence of hyphae or pseudohyphae). Images of lung histopathology after C. albicans TBC in mice are provided in Additional file 2.

C. albicans tracheobronchial colonization in mice and dose-dependent pathophysiological effects. A. C. albicans clearance from lungs. C. albicans loads in lungs two days after the intratracheal instillation of 1 × 105 and 1 × 106 CFU/mouse. CFU were counted on YPD plates. The data are means ± standard error (SE) (indicated by error bars). n = 5 mice per group. B. Effect of C. albicans on alveolar-capillary barrier permeability. Evaluation of endothelial permeability (EP) of the alveolar-capillary barrier to 125I-labeled bovine serum albumin two days after the intratracheal instillation of 1 × 105 and 1 × 106 CFU/mouse of C. albicans. The data are means ± SE (indicated by error bars). n = 5 mice per group.

Effect of prior C. albicans tracheobronchial colonization on P. aeruginosa pneumonia

We next addressed the issue whether prior C. albicans colonization in the lungs has an impact on the P. aeruginosa pathogenicity. When recording mortality over the course of four days post-infection, prior C. albicans airway colonization did not affect survival rate in case of subsequent P. aeruginosa infection (Figure 2A), although a trend toward an increased mortality was noted in the Pa group, but did not reach a statistical significance.

Effect of previous C. albicans tracheobronchial colonization on P. aeruginosa -related lung injury. A. BALB/c mice survival. Effect of C. albicans (Ca), P. aeruginosa (Pa), and P. aeruginosa after C. albicans (CaPa) on mouse survival during four days after intratracheal instillation of a dose of 1 × 105 CFU/mouse of C. albicans at T0 and of 1 × 107 CFU/mouse for P. aeruginosa administrated at Day 2 post-colonization. n = 8 mice per group. B. Effect of C. albicans and P. aeruginosa on alveolar-capillary barrier permeability. Evaluation of endothelial permeability (EP) of the alveolar-capillary barrier to 125I-labeled bovine serum albumin four days after the intratracheal instillation of a saline solution (Ctr) and in Ca, Pa, CaPa groups. The data are means ± SE (indicated by error bars). n = 8 mice per group.

Regarding lung endothelial permeability at Day 4, the efflux of the protein tracer in the CaPa-group was statistically greater than both the control- and Ca-groups (P < 0.01) but significantly lower than in the Pa-group (P < 0.001) (Figure 2B). In lung cultures at Day 4, the Pa-group showed a significant higher amount of live bacteria in lungs in comparison to the CaPa-group (P < 0.001) indicating that previous C. albicans airway colonization promoted the clearance of P. aeruginosa from the lungs (Figure 3). Also, in blood cultures at Day 4, P. aeruginosa detection was negative in the CaPa-group whereas they were still positive in 25% of the cases in the Pa-group (Table 2). No further C. albicans systemic dissemination was evidenced in the CaPa-group. The onset of P. aeruginosa pneumonia after C. albicans colonization did not affect lung C. albicans growth, which remained negative during the study period.

P. aeruginosa CFU count in lungs. Live P. aeruginosa count in lung homogenates (CFU/ml) at Day 4 in Ctr, Ca, Pa, CaPa groups and caspofungin-treated group at the dose of 1 mg/kg the first day and 0.8 mg/kg the following days until Day 4, from T0 (CaPaCasp0) or from Day 1 (CaPaCasp1). The data are means ± SE (indicated by error bars). n = 4 mice per group.

An important inflammatory cell infiltration within bronchiole and in the surrounding lung parenchyma was observed in mice receiving P. aeruginosa as evidenced by the histological score of lung sections (Figure 4A). Conversely, the CaPa-group had a significantly lower score of pathological lesions than the Pa-group on the histological score of lung sections (P < 0.05) (Figure 4A). Lung immunostaining at Day 4 showed the presence of C. albicans blastoconidia exclusively (Figure 4C-Images a and b). Together, our results suggest that C. albicans colonization prior to P. aeruginosa infection decreases the P. aeruginosa bacterial load and minimizes the lung lesions.

Lung histopathology after sequential infection with C. albicans and P. aeruginosa in mice. A. Histological score of lung sections from BALB/c mice on Day 4. Peribranchiol and perivascular lung inflammation in mice was measured by two independent blinded examiners. Data are expressed as mean ±SE for each group. P < 0.05 for CaPa vs Pa mice. B. Immunofluorescence and periodic acid Schiff staining for C. albicans localization in lungs of BALB/c mice on Day 4. (a) Representative section of lung from mice challenged with both C. albicans and P. aeruginosa stained with fluorescent galenthus nivalis lectin (GNL) specific for terminal α-D-mannosyl, preferentially α-1,3 residues of C. albicans. The scale bars represent 10 μm. (b) Lung section from mouse receiving C. albicans and P. aeruginosae stained with PAS (periodic acid Schiff). The scale bars represent 5 μm.

Effect of antifungal treatment on C. albicans interference with P. aeruginosa pneumonia

Antifungal caspofungin has been used to test whether it might reverse the effect of C. albicans airway colonization on subsequent P. aeruginosa pneumonia. The treatment was initiated upon infection at T0 or after a delay at Day 1 post-colonization. The fungicidal effect of caspofungin in mouse lungs was previously assessed at Day 2 and no positive fungal cultures were collected in both the CaCasp0- and the CaCasp1-groups (data not shown). Furthermore, the lack of impact of caspofungin on endothelial permeability was also confirmed at Day 1 after a single intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg/kg of caspofungin in control saline solution-instilled mice (data not shown). Caspofungin administration from T0 reversed the effect of previous airway colonization by C. albicans on P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury (Figure 5). Thus, when the antifungal is administered early the lung injury induced by P. aeruginosa persists and the endothelial permeability showed by means of protein tracer leak is enhanced to the level of the Pa-group. In contrast, caspofungin administration from Day 1 did not reverse the C. albicans effect as an equal amount of protein efflux tracer was observed in the Ca- and CaPa-groups and was still significantly different from the Pa-group (P < 0.001).

Effect of caspofungin on alveolar-capillary barrier permeability. Evaluation of endothelial permeability (EP) of the alveolar-capillary barrier to 125I-labeled bovine serum albumin at Day 4 in Ctr, Ca, Pa, CaPa groups and caspofungin-treated group at the dose of 1 mg/kg the first day and 0.8 mg/kg the following days until Day 4, from T0 (CaPaCasp0) or from Day 1 (CaPaCasp1). The data are means ± SE (indicated by error bars). n = 8 mice per group.

Regarding lung bacterial counts at Day 4, the effect of caspofungin was different depending on the time of administration (Figure 3). Administration from T0 (the CaPaCasp0-group) significantly abolished the decrease of positive specimens observed in the CaPa-group (P < 0.001). Conversely, delayed administration from day 1 (CaPaCasp1-group) resulted in collecting a roughly similar amount of live P. aeruginosa in lungs than in the CaPa-group creating a significant difference with the CaPaCasp0-group (P < 0.01).

Discussion

The present study was designed to determine the contribution of C. albicans airway colonization to P. aeruginosa pathogenicity in immunocompetent mice. Our results indicate that prior short-term C. albicans airway colonization reduced P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury and the amount of live P. aeruginosa in lungs. This effect is reversed by fungicidal drug caspofungin when initiated concomitantly to C. albicans infection.

The prerequisite to the study was the set-up of tracheobronchial colonization by C. albicans according to the definition of colonization, which is the presence of a pathogen that does not cause damages on the lung parenchyma. The dose of 1 × 105 CFU of C. albicans per mouse matched with this criterion as no invasive disease occurred. After P. aeruginosa infection, a trend toward a higher survival rate in the C. albicans-colonized mice was observed. This result is consistent with data comparing groups of mice instilled simultaneously with P. aeruginosa and C. albicans or with P. aeruginosa alone showing a significant difference of survival in favor of the C. albicans-colonized group at Day 7 [23]. Then, it was found that previous C. albicans airway colonization was associated with an increase in lung P. aeruginosa clearance compared to the non-colonized-group. These data differ from the previous study, which did not detect a significant decrease in quantitative bacterial burden in the group receiving simultaneous administration of C. albicans along with P. aeruginosa [23]. However, a major difference is that bacterial loads were recorded early after the co-infection between 3 and 20 h. Another study, which addressed the issue of prevalence of P. aeruginosa pneumonia in rats colonized by C. albicans, evaluated the quantitative bacterial cultures of P. aeruginosa in rat lungs at 48 h post-infection [16]. Subsequent to C. albicans colonization obtained by intratracheal instillation (2 × 106 CFU per rat three days in a row), a low dose of P. aeruginosa (1 × 104 CFU per rat) was delivered at Day 2 post-colonization. The bacterial burden was significantly higher at 48 h in rats instilled with C. albicans before P. aeruginosa compared to rats instilled with saline solution or ethanol-killed C. albicans before P. aeruginosa. Contrary, in our experimental model, P. aeruginosa dissemination in the bloodstream showed a trend toward a decrease in the case of prior C. albicans colonization. Although bacterial dissemination is multifactorial depending on the magnitude of alveolar-capillary barrier injury [24] as well as the strain virulence and the size of the inoculum [25], the decrease was most likely due to the decrease of alveolar-capillary barrier injury since the P. aeruginosa strain used and the size of the inoculum administrated were identical in both groups. Regarding histolopathologic results, the inflammation score decreased in the case of previous C. albicans airway colonization in comparison to P. aeruginosa infection alone suggesting that primary immune activation could reduce P. aeruginosa pathogenicity. This observation was consistent with a decrease in P. aeruginosa lung loads and a decrease in the lung permeability index in the CaPa group in comparison to the Pa group. These results differ from a study previously mentioned which concluded that previous C. albicans colonization lowered the threshold of P. aeruginosa load necessary to induce parenchymal injury since in rats given C. albicans, histologic aspect of P. aeruginosa pneumonia was significantly more frequent than in controls or ethanol-killed C. albicans rats [16]. Overall, the results may differ between mice and rats, and between different strains of P. aeruginosa owing to differential susceptibility to pneumonia.

In the second part of this study, the influence of fungicidal caspofungin was tested. The use of caspofungin aimed at detecting a difference between colonization with live or killed C. albicans. For that purpose, two target times for treatment initiation were chosen, from T0 or from Day 1. Regarding the alveolar-capillary barrier injury, the use of caspofungin resulted in distinct effects: reversal of the decrease in the protein tracer leakage when initiated at T0 or maintenance of the decrease in the protein tracer leakage when initiated at Day 1. The difference observed between the T0- and the Day 1-treated group suggests that the viability and/or the growth of C. albicans makes a difference in reducing the magnitude of alveolar-capillary barrier injury.

Overall, these results raise three hypotheses: first, a competitive effect regarding the adhesion of the pathogens to lung epithelial surface. Indeed, they both use ligands to recognize the glycoconjugates at the surface of epithelial cells [26, 27]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that P. aeruginosa lectins LecA and LecB, which are involved in adhesion to epithelial cells, contribute to P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury [17]. The neutralization of these lectins by the administration of specific lectin inhibitors was remarkably effective in improving lung injury. C. albicans adherence to host tissue is controlled by the ALS (agglutinin-like sequence) gene family which encodes a group of glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol (GPI)-linked cell surface proteins that function as adhesins that bind to the cell surface [28]. The second hypothesis is a bactericidal effect mediated by higher-inducible lung mucosal innate response by live C. albicans. This hypothesis is supported by the decrease in inflammation score in case of previous C. albicans airway colonization in comparison to P. aeruginosa infection alone, and by the fact that T0 caspofungin treatment resulted in a higher rate of bacterial growth. Finally, C. albicans produces farnesol, a cell-to-cell signaling molecule that could act as a quorum-sensing antagonist of P. aeruginosa [14, 29]. The addition of farnesol to cultures of P. aeruginosa leads to decreased production of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) and the PQS-controlled downstream virulence factor, pyocyanin [30]. Furthermore, it has been shown that the C. albicans farnesol has also the ability to inhibit swarming motility in P. aeruginosa cystic fibrosis clinical isolates [31]. All together, the reduction in PQS-pyocyanin production and swarming mobility may also have implications for the interaction between P. aeruginosa and the host.

The present study has several limitations that prevent extrapolating the results to the chronically colonized and/or critically ill patients at risk for VAP. First, the short term C. albicans colonization in the model does not correctly reflect the situation of these patients. Indeed, the amount of C. albicans in lungs cannot be substantially sustained over time in immunocompetent BALB/c mice, as already described elsewhere [32]. Consequently, P. aeruginosa pneumonia had to be generated only 48 hours after the prior fungal colonization. The addition of a control experimental group testing the impact of killed C. albicans would have been of interest to assess the need of live C. albicans to produce the effects described. Concern can also be raised regarding some in vitro data indicating a decrease of P. aeruginosa growth following exposure to halogenated anesthetics [33], although it occurred after several hours of exposure and has not been investigated in vivo. The short duration of mutual contact and interaction of C. albicans and P. aeruginosa in the airways (48 h) represents another potential bias of the present study. Furthermore, a dose/effect study testing various doses of P. aeruginosa to generate pneumonia could better document the in vivo dynamics of bacterial-fungal interactions. Performing microbial CFU counts in spleen and liver could better assess microbial dissemination. Finally, this relationship is studied in normal lungs and in the absence of any airway prosthetic device, which largely promotes microbial community networking [12].

Conclusions

The present results demonstrate that P. aeruginosa-related lung injury is reduced when preceded by short term C. albicans airway colonization. Regarding the use of the antifungal drug caspofungin, reduced P. aeruginosa-related lung injury is reversed when the treatment is initiated at T0, and maintained when the treatment is started one day after the onset of C. albicans colonization. The study illustrates the complex relationships between fungi and bacteria consistently with a number of other works in which cross-kingdom interactions result in very different effects (from synergy to antagonism). Additionally, the impact of antifungal agents on the fungal-bacterial ecosystem is poorly understood. Further in vitro and in vivo studies are required using cell wall C. albicans extracts such as glucans or mannans during P. aeruginosa infection in order to better understand the molecular mechanisms involved.

Key messages

• In this study, murine P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury measured at 48 h post-infection is reduced when preceded by short term C. albicans airway colonization.

• Additionally, short-term C. albicans colonization results in a reduction of the amount of P. aeruginosa in murine lungs at 48 h post-infection.

• Using the fungicidal drug caspofungin upon C. albicans colonization reverses these effects.

Abbreviations

- ALS:

-

agglutinin-like sequence

- BCP:

-

bromocresol purple

- Ca:

-

Candida albicans

- CaPaCasp:

-

Candida albicans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Caspofungin

- CFU:

-

colony-forming units

- GPI:

-

glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol

- SDA:

-

Sabouraud dextrose agar

- TBC:

-

Tracheobronchial colonization

- VAP:

-

ventilator-acquired pneumonia

- YPD:

-

yeast peptone dextrose.

References

Safdar N, Dezfulian C, Collard HR, Saint S: Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33: 2184-2193. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000181731.53912.D9.

Markowicz P, Wolff M, Djedaini K, Cohen Y, Chastre J, Delclaux C, Merrer J, Herman B, Veber B, Fontaine A, Dreyfuss D: Multicenter prospective study of ventilator-associated pneumonia during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. ARDS Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000, 161: 1942-1948.

Chastre J, Fagon JY: Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 165: 867-903.

Kollef MH, Morrow LE, Niederman MS, Leeper KV, Anzueto A, Benz-Scott L, Rodino FJ: Clinical characteristics and treatment patterns among patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2006, 129: 1210-1218. 10.1378/chest.129.5.1210.

el-Ebiary M, Torres A, Fabregas N, de la Bellacasa JP, González J, Ramirez J, del Baño D, Hernández C, Jiménez de Anta MT: Significance of the isolation of Candida species from respiratory samples in critically ill, non-neutropenic patients: an immediate post-mortem histologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997, 156: 583-590.

Wood GC, Mueller EW, Croce MA, Boucher BA, Fabian TC: Candida sp. isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage: clinical significance in critically ill trauma patients. Intensive Care Med. 2006, 32: 599-603. 10.1007/s00134-005-0065-6.

Delisle MS, Williamson DR, Perreault MM, Albert M, Jiang X, Heyland DK: The clinical significance of Candida colonization of respiratory tract secretions in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2008, 23: 11-17. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.01.005.

Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Tafflet M, de Lassence A, Darmon M, Zahar JR, Adrie C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Cohen Y, Mourvillier B, Schlemmer B, Outcomerea Study Group: Candida colonization of the respiratory tract and subsequent Pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2006, 129: 110-117. 10.1378/chest.129.1.110.

Nseir S, Jozefowicz E, Cavestri B, Sendid B, Di Pompeo C, Dewavrin F, Favory R, Roussel-Delvallez M, Durocher A: Impact of antifungal treatment on Candida-Pseudomonas interaction: a preliminary retrospective case-control study. Intensive Care Med. 2007, 33: 137-142. 10.1007/s00134-006-0422-0.

Adair CG, Gorman SP, Feron BM, Byers LM, Jones DS, Goldsmith CE, Moore JE, Kerr JR, Curran MD, Hogg G, Webb CH, McCarthy GJ, Milligan KR: Implications of endotracheal tube biofilm for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 1999, 25: 1072-1076. 10.1007/s001340051014.

El-Azizi MA, Starks SE, Khardori N: Interactions of Candida albicans with other Candida spp. and bacteria in the biofilms. J Appl Microbiol. 2004, 96: 1067-1073. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02213.x.

Douglas LJ: Candida biofilms and their role in infection. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11: 30-36. 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)00002-1.

Hogan DA, Kolter R: Pseudomonas-Candida interactions: an ecological role for virulence factors. Science. 2002, 296: 2229-2232. 10.1126/science.1070784.

Hogan DA, Vik A, Kolter R: A Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule influences Candida albicans morphology. Mol Microbiol. 2004, 54: 1212-1223. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04349.x.

Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, Scheper MA, Leid JG, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME: Microbial interactions and differential protein expression in Staphylococcus aureus-Candida albicans dual-species biofilms. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010, 59: 493-503.

Roux D, Gaudry S, Dreyfuss D, El-Benna J, de Prost N, Denamur E, Saumon G, Ricard JD: Candida albicans impairs macrophage function and facilitates Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in rat. Crit Care Med. 2009, 37: 1062-1067. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819629d2.

Chemani C, Imberty A, de Bentzmann S, Pierre M, Wimmerovà M, Guery BP, Faure K: Role of LecA and LecB lectins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced lung injury and effect of carbohydrate ligands. Infect Immun. 2009, 77: 2065-2075. 10.1128/IAI.01204-08.

Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR: Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5'-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1984, 198: 179-182. 10.1007/BF00328721.

Jayr C, Garat C, Meignan M, Pittet JF, Zelter M, Matthay MA: Alveolar liquid and protein clearance in anesthetized ventilated rats. J Appl Physiol. 1994, 76: 2636-2642. 10.1063/1.357560.

Kwak YG, Song CH, Yi HK, Hwang GH, Kim PS, Lee KS, Lee YC: Involvement of PTEN in airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in bronchial asthma. J Clin Invest. 2003, 111: 1083-1092.

Fortier B, Hopwood V, Poulain D: Electric and chemical fusions for the production of monoclonal antibodies reacting with the in-vivo growth phase of Candida albicans. J Med Microbiol. 1988, 27: 239-245. 10.1099/00222615-27-4-239.

Jawhara S, Thuru X, Standaert-Vitse A, Jouault T, Mordon S, Sendid B, Desreumaux P, Poulain D: Colonization of mice by Candida albicans is promoted by chemically induced colitis and augments inflammatory responses through galectin-3. J Infect Dis. 2008, 197: 972-980. 10.1086/528990.

Fujita K, Tateda K, Kimura S, Saga T, Ishi Y, Yamagushi K: A novel aspect of interspecies communication in Candida and Pseudomonas: co-existence of Candida modulates dissemination and lethality in P. aeruginosa pulmonary infection [abstract]. Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC). 2008, 187: B70-

Kurahashi K, Kajikawa O, Sawa T, Ohara M, Gropper MA, Frank DW, Martin TR, Wiener-Kronish JP: Pathogenesis of septic shock in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Clin Invest. 1999, 104: 743-750. 10.1172/JCI7124.

Sawa T, Ohara M, Kurahashi K, Twining SS, Frank DW, Doroques DB, Long T, Gropper MA, Wiener-Kronish JP: In vitro cellular toxicity predicts Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in lung infections. Infect Immun. 1998, 66: 3242-3249.

Imberty A, Wimmerova M, Mitchell EP, Gilboa-Garber N: Structure of the lectins from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: insights into the molecular basis for host glycan recognition. Microb Infect. 2004, 6: 221-228. 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.10.016.

Sundstrom P: Adhesion in Candida spp. Cell Microbiol. 2002, 4: 461-469. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00206.x.

Filler SG: Candida-host cell receptor-ligand interactions. Curr Op Microbiol. 2006, 9: 333-339. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.005.

Hogan DA: Talking to themselves: autoregulation and quorum sensing in fungi. Eukaryotic Cell. 2006, 5: 613-619. 10.1128/EC.5.4.613-619.2006.

Cugini C, Hogan DA: Farnesol, a common sesquiterpene, inhibits PQS production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2007, 65: 896-906. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05840.x.

McAlester G, O'Gara F, Morrissey JP: Signal-mediated interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans. J Med Microbiol. 2008, 57: 563-569. 10.1099/jmm.0.47705-0.

Londono P, Gao XM, Bowe F, McPheat WL, Booth G, Dougan G: Evaluation of the intranasal challenge route in mice as a mucosal model for Candida albicans infection. Microbiology. 1998, 144: 2291-2298. 10.1099/00221287-144-8-2291.

Molliex S, Montravers P, Dureuil B, Desmonts JM: Halogenated anesthetics inhibit Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth in culture conditions reproducing the alveolar environment. Anesth Analg. 1998, 86: 1075-1078.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ana-Maria Dragoi who kindly provided useful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FA participated in the design of the study, carried out the in vivo experiments, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. SJ carried out the histological and immunofluorescence assays and helped to draft the manuscript. SN, BS KF, FV, CC, DP and BG participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Florence Ader, Samir Jawhara contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

13054_2011_9610_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: In vivoquantification of acute lung injury: alveolar-capillary barrier permeability. Method of measurement of alveolar-capillary barrier permeability. (PDF 82 KB)

13054_2011_9610_MOESM2_ESM.PDF

Additional file 2: Lung histopathology after C. albicans tracheobronchial colonization in mice. Supplemental figures of lung histopathology at Day 2 post-infection with C. albicans(PDF 1 MB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ader, F., Jawhara, S., Nseir, S. et al. Short term Candida albicans colonization reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa-related lung injury and bacterial burden in a murine model. Crit Care 15, R150 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10276

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10276