Abstract

Introduction

Although Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a leading pathogen responsible for ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), the excess in mortality associated with multi-resistance in patients with P. aeruginosa VAP (PA-VAP), taking into account confounders such as treatment adequacy and prior length of stay in the ICU, has not yet been adequately estimated.

Methods

A total of 223 episodes of PA-VAP recorded into the Outcomerea database were evaluated. Patients with ureido/carboxy-resistant P. aeruginosa (PRPA) were compared with those with ureido/carboxy-sensitive P. aeruginosa (PSPA) after matching on duration of ICU stay at VAP onset and adjustment for confounders.

Results

Factors associated with onset of PRPA-VAP were as follows: admission to the ICU with septic shock, broad-spectrum antimicrobials at admission, prior use of ureido/carboxypenicillin, and colonization with PRPA before infection. Adequate antimicrobial therapy was more often delayed in the PRPA group. The crude ICU mortality rate and the hospital mortality rate were not different between the PRPA and the PSPA groups. In multivariate analysis, after controlling for time in the ICU before VAP diagnosis, neither ICU death (odds ratio (OR) = 0.73; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.32 to 1.69; P = 0.46) nor hospital death (OR = 0.87; 95% CI: 0.38 to 1.99; P = 0.74) were increased in the presence of PRPA infection. This result remained unchanged in the subgroup of 87 patients who received adequate antimicrobial treatment on the day of VAP diagnosis.

Conclusions

After adjustment, and despite the more frequent delay in the initiation of an adequate antimicrobial therapy in these patients, resistance to ureido/carboxypenicillin was not associated with ICU or hospital death in patients with PA-VAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite many improvements in the management of mechanically-ventilated patients, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) remains the second leading cause of nosocomial infections in intensive care units (ICU). VAP has one of the highest mortality rates, ranking from 20 to 50% [1], and increases length of hospital stay, and hospital costs [2].

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a leading cause of nosocomial infections and one of the bacteria most frequently responsible for late-onset VAP. When VAP is documented by bronchoscopic techniques, P. aeruginosa is the most frequently isolated nosocomial bacteria, with more than 19% of the isolates. According to data collected by the French network REA-RAISIN during the year 2009, P. aeruginosa was the bacteria responsible for most nosocomial infections (17.3% of nosocomial infections) and for most VAP (22.3% of VAP) [3].

P. aeruginosa causes infection and damage to host tissues via the production of several extracellular virulence factors [4–7]. The P. aeruginosa genome is one of the largest bacterial genomes. Its large size reflects a great genetic and functional diversity, with a large number of genes predicted to encode outer membrane proteins such as those involved in adhesion, motility, antibiotic efflux and virulence factor export [8].

In addition to being intrinsically resistant to several antimicrobial agents, P. aeruginosa often acquires mechanisms of resistance to other antibiotics, especially in ICU patients. This increasing antibiotic resistance makes the treatment of P. aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia (PA-VAP) more difficult and more expensive.

Few published studies report the impact of antibiotic resistance on the outcome of PA-VAP [9, 10]. Their authors conclude that antibiotic resistance did not significantly affect ICU mortality. However, appropriate adjustments for differences in epidemiological and clinical characteristics between patients with resistant and susceptible infections are complex, leading to results lacking in controls for confounding factors.

The goal of this study was to estimate the mortality attributable to piperacillin resistance, while taking into account differences in the elapsed time between disease onset and the initiation of an adequate antimicrobial therapy.

Material and methods

Study design and data source

We conducted an exposed/non-exposed study nested in a multicenter cohort (the OUTCOMEREA® database) from January 1997 to January 2008. The database, fed by 12 French ICUs, is designed to record daily disease severity and occurrence of iatrogenic events.

The senior physicians of the participating ICUs, who are closely involved in establishing the database, recorded the data daily. For each patient, the investigators entered the data into a computer case-report form using the data capture softwares VIGIREA and recently RHEA® (OUTCOMEREA™, Rosny-sous-Bois, France). All records were imported to the OUTCOMEREA® database. All codes and definitions were defined in writing before the start of the data collection.

The following data were collected: age, sex, comorbidities assessed according to the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II definitions [11], severity of illness both at ICU admission and daily during the ICU stay assessed using the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II [12] and the Logistic Organ Dysfunction (LOD) score [13], admission category (medical, scheduled surgery, or unscheduled surgery), admission diagnosis, whether the patient was transferred from a hospital ward (defined as a stay in an acute-bed ward ≥24 hours immediately before ICU admission), lengths of ICU and hospital stays, and vital status at discharge from ICU and from the hospital. Invasive procedures (placement of an arterial or central venous catheter, and endotracheal intubation), treatments of organ failure (catecholamine infusion, mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis), and antibiotic use were also captured.

Suspected VAP was defined as the development of persistent pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiographs combined with purulent tracheal secretions and/or body temperature ≥38.5°C or ≤36.5°C and/or peripheral blood leukocyte count ≥10·109/L or ≤4·109/L. Before receiving any new antibiotic therapy, all patients with suspected VAP underwent fiber optic bronchoscopy with a protected specimen brush and/or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), single-sheathed blind plugged telescopic catheter specimen collection, or tracheal aspiration, with quantitative cultures of collected specimens. The model was established using solely confirmed VAP. This was defined as a positive culture result from a protected specimen brush (≥103 cfu/ml), plugged telescopic catheter specimen (≥103 cfu/ml), BAL fluid specimen (≥104 cfu/ml), or quantitative endotracheal aspirate (≥105 cfu/ml) [14]. The investigators recorded prospectively the date of appropriate therapy start (that is, the date when at least one of the antibiotics had in vitro activity against the strains recovered) but the complete antimicrobial susceptibility testing results were not captured in the OUTCOMEREA ® database.

A special request was performed retrospectively to collect information about antibiotic susceptibility profiles of all recovered strains of P. aeruginosa. Strains intermediate or resistant to one antimicrobial were considered as resistant.

The quality control processes are detailed elsewhere [14]. Briefly, it combined an initial training process, a manual, and automatic checking for inconsistencies and feedback to investigators, a data-capture training course, and a bi-annual audit of patients' files. Moreover, each ICU investigator was involved in the data analysis and study reporting.

Study population and definitions

All patients in the database with a confirmed PA-VAP were eligible.

Patients with mechanical ventilation at admission who developed a resistant PA-VAP were compared to patients who developed sensitive PA-VAP. Among patients who contracted several episodes of PA-VAP, only the first episode was included in the analysis. We compared patients with a first episode of PA-VAP due to Ureido/carboxypenicillin sensitive (PSPA-VAP) to those having resistant strains (PRPA-VAP).

Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as numerical values and percentages for categorical variables, and as medians and inter-quartiles (Q1 to Q3) for continuous variables.

Using an algorithm [15], we utilized a N:M matching on the duration of the ICU stay prior to PA-VAP onset.

Comparisons between matched patients were initially completed based on univariate conditional logistic regression. Multivariate conditional logistic regression was then used to examine the association between PRPA-VAP and ICU and hospital mortality. This was adjusted for potential confounding variables (that is, variables that had a P-v alue ≤10 in bivariate analysis). Wald χ2 tests were used to determine the significance of each variable. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence were calculated for each parameter estimate. A P- value less than .05 was considered significant. Analyses were computed using the SAS 9.1 software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA)

Ethical issues

According to French law, this study did not require patient consent, as it involved research on a database. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Centres d'Investigation Rhône-Alpes-Auvergne.

Results

During the study period, of the 9,985 patients included in our OUTCOMEREA ® database, 4,422 received mechanical ventilation for more than two days, and 223 experienced at least one episode of PA VAP (361 episodes of PA VAP were recorded). PRPA-VAP was diagnosed in 70 patients, and PSPA-VAP was diagnosed in 153 patients (Table 1). Resistance to other antimicrobials were as follows: imipenem (25.6%, 26 not recorded), ceftazidime (83.8%, 19 not recorded), ciprofloxacin (38.5%, 55 not recorded), amikacin (17.2%, 25 not recorded), colistin (4.2%, 80 not recorded). The median length of ICU stay was 29 days. The flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 1.

Factors associated with Ureido-/carboxypenicillin resistance

Clinical characteristics at ICU admission and within 48 hours before VAP diagnosis for PRPA and PSPA-VAP are listed in Table 2. The groups were similar with regard to sex, age, SAPS II, immunosuppression, underlying diseases and proportions of medical and surgical patients.

Patients with PRPA-VAP were more likely to have septic shock at ICU admission (28.6% (20 of 70 patients) vs. 15% (23 of 153 patients); P = 0.02), and to have a previous carriage or colonization with a multiresistant strain of PA. Positive blood culture (between Day -2 VAP diagnosis and Day +2) was more frequent in the PRPA-VAP than in the PSPA-VAP group (10% (7 of 70 patients) vs. 3.9% (6 of 153 patients); P = 0.054).

Details of antimicrobials received prior to VAP infection are listed in Table 3. Compared to patients with PSPA-VAP, patients with PRPA-VAP were significantly more likely to have received broad-spectrum antimicrobials during their admission in the ICU (77.1% (54 of 70 patients) vs. 60.1% (92 of 153 patients); P = 0.03). Before VAP diagnosis, patients with PRPA-VAP were more likely to have received tazobactam therapy (18.6% (13 of 70 patients) vs. 9.2% (14 of 153 patients); P = 0.01), and to have received ureidopenicillins or carboxypenicillins therapy (31.4% (22 of 70 patients) vs. 13.1% (20 of 153 patients); P = 0.0004). Differences in the use of fluoroquinolones therapy did not reach statistical significance (24.3% in PRPA group (7 of 70 patients) vs. 13.1% in PSPA group (20 of 153 patients); P = 0.058).

Percentage of antibiotic-free days was different between the two groups for tazobactam, and ureidopenicillins-carboxypenicillins. Compared with patients with PRPA-VAP, patients with PSPA-VAP had more tazobactam-free days (P = 0.019), and less ureidopenicillins-carboxypenicillins-free days (P = 0.007).

Adequate antibiotic therapy was started within 24 h after the diagnosis of VAP for 36 patients (51.4%) in the PRPA-VAP group, versus 117 patients (76.5%) in the PSPA-VAP group (P = 0.001). Adequate antibiotic therapy was started at least two days after PA VAP diagnosis for 25 patients (35.7%) in the PRPA-VAP group, versus for 26 patients (17%) in the PSPA-VAP group (P = 0.007). Use of bi- or tri-antimicrobial-therapy was similar between groups. Antibiotic therapy before ICU discharge was not adequate for 9 patients (12.9%) in the PRPA-VAP group, versus 10 patients (6.5%) in the PSPA-VAP group (P = 0.054).

The rate of recurrence was not influenced by resistance (PSPA-VAP 28 (18.3%) vs PRPA-VAP 11 (15.7%), P = 0.83).

Compared with patients with PSPA-VAP, PRPA-VAP patients had similar lengths of ICU stay prior to VAP (11 days (range, 6 to 18 days) vs. 9 days (range, 6 to 17 days); P = 0.53). PRPA-VAP and PSPA-VAP were associated with similar crude ICU mortality (38% (25 of 70 patients) vs. 41% (62 of 153 patients); P = 0.56) as well as in hospital mortality (43% (30 of 70 patients) vs. 44% (68 of 153 patients); P = 0.85).

Risk factors for death

Risk factors for ICU death are listed in Table 1. Risk factors found for ICU death at admission were: age, at least one chronic illness, admission for cardiac illness or septic shock, Simplified Acute Physiology Score version II (SAPS II), organ dysfunction scores (LOD, SOFA). Two days before PA-VAP, risk factors for ICU death were: treatment with vasopressors, treatment with steroids, SAPS II, and organ dysfunction scores (LOD, SOFA).

Resistance to Ureido/carboxypenicillin was not a risk factor for ICU death. After adjusting for other risk factors of death, differences between groups and duration of ICU stay prior to the VAP onset, resistance to ureido/carboxypenicillins was no more a risk factor for death (Table 4).

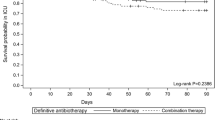

Similarly, resistance to imipenem, ceftazidime, amikacin, ciprofloxacin and colistin (Figure 2) was not associated with ICU death or hospital death.

Resistance to other antimicrobials of ureido/carboxy susceptible and resistant strains ( n = 129). AMK, amikacine; CFP, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; COL, colimycin; CTZ, Ceftazidime; IMI, Imipenem; PR-PA piperacillin-resistant P. aeruginosa; PSPA, piperacillin-susceptible P. aeruginosa; (*) Missing values: some antibiotics were not tested by the microbiology lab or not found, CTZ 2 (1%), CFP 63 (31%), IMI 7 (3%), CIP 10 (5%), AMK 8 (4%), COL 60 (30%). All the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

The results remained unchanged when analysis was restricted to the 87 patients adequately treated the day of the infection onset (OR for ICU mortality 1.22 (95% CI, 0.31 to 4.78; P = 0.78); OR for hospital mortality, 1.10 (95% CI, 0.29 to 4.10; P = 0.89)).

Discussion

To date, our study is one of the largest to have evaluated the impact of piperacillin resistance in PA-VAP [9, 10]. All data were carefully recorded by senior physicians on computer forms. Definitions and antimicrobial treatments were in accordance with international guidelines. The major result is that piperacillin resistance is associated with a higher rate of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy. Unadjusted mortality was similar in PSPA-VAP and PRPA-VAP groups. After careful adjustment for time in the ICU at VAP diagnosis and for parameters that differ between the PRPA and the PSPA groups (severity at admission, previous antibiotic treatment, and adequacy of antimicrobial treatment), piperacillin resistance was found to not be associated with ICU or hospital death in the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

We observed a high rate of P. aeruginosa strains resistant to piperacillin (31%). This is in agreement with previous studies conducted in Europe [16]. The percentage of P. aeruginosa resistance to ureidopenicillin reached 37% in the EPIC I study which included only bacterial strains from the European ICU [17]. The pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa is multifactorial, strain-specific, and dependent on complex host factors. Morbidity and mortality for patients infected with piperacillin resistant P. aeruginosa might be related to the virulence of the bacteria but also to the antimicrobial treatment administered. Both virulence factor genes and antimicrobial resistance genes are mostly carried by transposons and integrons, that is, genetic entities able to mediate their own translocation from one DNA site to another one. Integrons are particularly dominant contributors to the development of multi-drug resistant P. aeruginosa strains [8].

Conceivably PRPA strains may be more virulent than PSPA strains. P. aeruginosa exhibits multiple virulence factors: some surface factors including flagellum, pili, LPS, some secreted factors including a type III secretion system that confers the ability to inject toxins into host cells; quorum-sensing molecules (a complex regulatory circuit involving cell-to-cell signalling) and alginate. Some studies conducted in vitro and in experimental models found that virulence of P. aeruginosa might be reduced in mutant resistant strains of P. aeruginosa suggesting that antibiotic resistance imposes a fitness cost on the bacteria [18, 19]. Recent data on in vitro mutants have suggested that virulence of P. aeruginosa might be reduced when mex efflux systems are overexpressed [20]. Indeed, it seems that mutant strains may recover their fitness or virulence by compensatory mutations. Hoquet et al. conducted a study on 120 strains of P. aeruginosa from episodes of septicaemia: 75% of strains displayed a significant resistance to one or more of the tested antimicrobials. P. aeruginosa may accumulate intrinsic (chromosomal) and exogenous resistance mechanisms without losing its ability to generate severe bloodstream infections [21].

Jeannot et al. focused on clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa mexCD-oprJ overproducing efflux mutants: mexCD-oprJ up regulation (which correlated with increase resistance to ciprofloxacin and cefepime, increased susceptibility to ticarcillin, aztreonam, imipenem and aminoglycosides), associated with impaired bacterial fitness although it was isolated from confirmed cases of clinical infections [22].

In our study, 153 of 223 patients received adequate antibiotic therapy within 24 hours after pneumonia suspicion (51.4% in the PRPA group and 76.5% in the PSPA group). Garnacho-Montero et al.[23] evaluated the impact on the outcome of a monotherapy or a combined therapy in patients with PA-VAP. They showed that the initial use of a combination therapy significantly reduced the likelihood of inappropriate therapy, which was associated with a higher risk of death. However, the administration of only one effective antimicrobial or combination therapy provided similar outcomes. For Kang et al. adequate initial antibiotic therapy appeared to be one of the most important factors in the treatment of severe P. aeruginosa infections, as they observed a trend towards higher mortality rates as the interval prior to appropriate treatment increased. However, their results were not statistically significant [24].

In our study, antibiotic resistant strains were associated with an increased risk of inadequate antimicrobial therapy, but we did not find that PRPA influenced recurrence, relapse or mortality.

We previously showed that the highest impact of inappropriate therapy on prognosis obtained when patients' severity score is intermediate [25, 26]. The absence of impact of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy on the prognosis might be due to the high severity of patients at VAP onset (SOFA at 6 in median in the present study).

As any delay in the initiation of an adequate antimicrobial therapy is known to be a major prognostic risk factor in nosocomial infection due to P. aeruginosa[24, 27], the absence of an increased mortality, where the initial antibiotic therapy is less often appropriate, would plead in favour of impaired virulence of the resistant strains.

In order to control this potential confounding factor, we analysed the subgroup of 87 patients adequately treated within 24 hours after VAP diagnosis. In the multivariate analysis, the only risk factor of ICU or hospital death was having at least one chronic illness, not piperacillin resistance.

Other studies comparing outcomes of susceptible and resistant P. aeruginosa infections are scarce. Recently, Combes et al. conducted a post-hoc analysis of the PNEUMA randomized study, which involved only cases of adequately treated PA VAP [9]. PRPA-VAP was associated with a higher mortality than PSPA-VAP. However, after adjustment for age, female gender, underlying comorbidities, and SOFA score, piperacillin resistance was no longer associated with mortality (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 0.72 to 5.61; P = 0.194). Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study evaluating the epidemiological characteristics of 135 episodes of VAP caused by PRPA or PSPA, Trouillet et al. did not find any increased death rates for PRPA infections [10]. Data from the few studies concerning P.aeruginosa bacteraemia reported similar results. Blot et al. conducted a retrospective study on antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant nosocomial gram-negative bacilli bacteraemia in critically ill patients. Factors associated with in-hospital mortality were the age, a high-risk source of bacteraemia, and APACHE II score, but not antibiotic resistance [28]. This result is in accordance with other studies conducted about gram-negative bacilli infection [29], as well as Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia [30].

Some studies have described higher mortality rates in association with infections caused by antibiotic resistant P. aeruginosa. In a retrospective matched control study by Aloush et al., patients infected with multi-resistant P. aeruginosa strains had higher mortality rates and increased durations of hospital stay, but the control patients did not have P. aeruginosa infections [31]. In an older study evaluating health and economic outcomes of resistant Pseudomonas infections, the same group found that, although the patients with resistant strain at hospital admission did not have a poorer overall prognosis, the emergence of resistant strains during the hospital stay was associated with a prolonged length of stay and a higher hospital mortality rate [32].

Our study highlighted the major role of previous antibiotic therapy. The emergence of PRPA: PRPA VAP episodes were significantly associated with the administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobials at admission to ICU, such as ureidopenicillins, carboxypenicillins or fluoroquinolones. These findings are in accordance with the results of Harris et al.[33], who found that the piperacillin-tazobactam exposure was the major factor that predispose for the development of an infection with a multidrug resistant P. aeruginosa. In a clinical study, Reinhardt et al. found that resistant P. aeruginosa is selected in less than seven days in patients treated with piperacillin-tazobactam [34].

In contrast to previous studies [32, 33, 35], in our work, imipenem was not associated with VAP due to PRPA. But the main resistance mechanism to carbapenem is loss of the porin oprD, which leads to a selective resistance to these antibiotics.

Our study confirms results of the case-control study conducted by Harris et al. in that previous exposure to piperacillin: piperacillin-tazobactam was statistically associated with the isolation of piperacillin-tazobactam-resistant P. aeruginosa (OR 8.63; 95% CI 6.11 to 12.20; P < 0.0001) [33]. In an observational study comparing the relative risks of emergence of resistant P. aeruginosa associated with four individual antipseudomonal agents, Carmeli et al. demonstrated that there was an significant association between piperacillin treatment and the emergence of piperacillin resistance (HR = 5.2; P = 0.01) [32].

In our study, fluoroquinolones treatment in the week prior to VAP was an independent factor associated with hospital death. Few data could explain this result. The expression of mexAB-oprM, responsible for acquired resistance to fluoroquinolones is regulated by the quorum-sensing, and, therefore, is known to be growth-phase dependent [36, 37]. We suggest that the overexpression of the porin mexAB-oprM could be synchronized with a hyper-production of bacterial virulence factors, leading to a very virulent bacterial inoculum.

Results on the role of fluoroquinolones in the emergence of piperacillin-resistant P. aeruginosa were of borderline statistical significance. Trouillet et al. suggested that receiving any fluoroquinolone may be a risk factor for acquiring piperacillin-resistant P. aeruginosa[10]. In a cohort study, Carmeli et al. also found previous ciprofloxacin treatment was a risk factor of the emergence of antibiotic-resistant P. aeruginosa (hazard ratio 9.2; P = 0.04) [32]. But in contrast to these previous studies, we did not found any role of carpapenems in the emergence of PRPA.

Duration of exposure to these antibiotics should also be taken into consideration. In a case-control study conducted by Paramythiotou et al., among 34 patients with multi-drug resistant P. aeruginosa, a previous treatment with ciprofloxacin or imipenem was a significant risk factor for the acquisition of multi-drug resistance only when the duration of the treatment was longer than the median duration of treatment with these antimicrobials observed in that study [38].

Our study has several limitations. First, we used data prospectively collected in a large database that was not specifically designed for the present subject. However, all data were collected prospectively, with special attention to nosocomial infections and treatment adequacy. VAP was consistently documented by quantitative cultures of distal pulmonary specimens, and all patients were observed until ICU and hospital discharge.

Second, we have no data about MICs of strains to antimicrobials and we did not determine plasma antimicrobial levels. PK/PD optimization may have affected the outcome of VAP. However, antimicrobials used in the study's ICUs comply with international guidelines and aminoglycosides were used when appropriate.

Conclusions

In summary, after controlling for the duration of mechanical ventilation before VAP, piperacillin resistance is not significantly associated with ICU death or hospital death in patients with PA-VAP, despite the more frequent delay in the initiation of an adequate antimicrobial therapy observed in the PRPA group. This result pleads in favour of an impaired virulence of the resistant strains of P. aeruginosa, and should be confirmed by further studies conducted by physicians and bacteriologists.

Key messages

-

P. aeruginosa resistance to ureido/carboxypenicillin is associated with a significant decrease of adequacy of probabilistic antimicrobial therapy.

-

The absence of over-mortality associated with resistance may suggest a lower virulence of the more resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa strains.

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- BAL:

-

bronchoalveolar lavage

- LOD:

-

logistic organ dysfunction score

- PA-VAP:

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia

- PRPA:

-

ureido/carboxy resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- PSPA:

-

ureido/carboxy sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- SAPS:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- VAP:

-

ventilator-associated pneumonia.

References

NNIS: National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control 2004, 32: 470-485.

Chastre J, Fagon JY: Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165: 867-903.

REA-RAISIN Annual report 2009[http://www.cclinparisnord.org/REACAT/REA2009/rea_raisin_resultats2009.pdf]

Passador L, Cook JM, Gambello MJ, Rust L, Iglewski BH: Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science (New York, NY) 1993, 260: 1127-1130. 10.1126/science.8493556

Singh G, Wu B, Baek MS, Camargo A, Nguyen A, Slusher NA, Srinivasan R, Wiener-Kronish JP, Lynch SV: Secretion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III cytotoxins is dependent on pseudomonas quinolone signal concentration. Microb Pathog 2010, 49: 196-203. 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.05.013

Kohler T, Guanella R, Carlet J, van Delden C: Quorum sensing-dependent virulence during Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonisation and pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. Thorax 2010, 65: 703-710. 10.1136/thx.2009.133082

Hauser AR, Cobb E, Bodi M, Mariscal D, Valles J, Engel JN, Rello J: Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 521-528. 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00005

Kung VL, Ozer EA, Hauser AR: The accessory genome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2010, 74: 621-641. 10.1128/MMBR.00027-10

Combes A, Luyt CE, Fagon JY, Wolff M, Trouillet JL, Chastre J: Impact of piperacillin resistance on the outcome of Pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 1970-1978. 10.1007/s00134-006-0355-7

Trouillet JL, Vuagnat A, Combes A, Kassis N, Chastre J, Gibert C: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia: comparison of episodes due to piperacillin-resistant versus piperacillin-susceptible organisms. Clin Infect Dis 2002, 34: 1047-1054. 10.1086/339488

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE: APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985, 13: 818-829. 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009

Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F: A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 1993, 270: 2957-2963. 10.1001/jama.270.24.2957

Timsit JF, Fosse JP, Troche G, De Lassence A, Alberti C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Bornstain C, Adrie C, Cheval C, Chevret S: Calibration and discrimination by daily Logistic Organ Dysfunction scoring comparatively with daily Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scoring for predicting hospital mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 2003-2013. 10.1097/00003246-200209000-00009

Zahar JR, Nguile-Makao M, Francais A, Schwebel C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goldgran-Toledano D, Azoulay E, Thuong M, Jamali S, Cohen Y, de Lassence A, Timsit JF: Predicting the risk of documented ventilator-associated pneumonia for benchmarking: construction and validation of a score. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 2545-2551. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a38109

OUTCOMEREA: the matching N:M macro using the SAS software[http://www.outcomerea.org/Telecharger-document/286-Matching-NM.html]

Gales AC, Jones RN, Turnidge J, Rennie R, Ramphal R: Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates: Occurence Rates, Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns, and Molecular Typing in the Global SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997-1999. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 32: S146-155. 10.1086/320186

Vincent JL: Microbial resistance: lessons from the EPIC study. European Prevalence of Infection. Intensive Care Med 2000, 26: S3-8. 10.1007/s001340051111

Hirataka Y, Srikumar R, Poole K, Gotoh N, Suematsu T, Kohno S, Kamihira S, Hancock RE, Speert DP: Multidrug efflux systems play an important role in the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Exp Med 2002, 196: 109-118. 10.1084/jem.20020005

Sanchez P, Linares JF, Ruiz-Diez B, Campanario E, Navas A, Baquero F, Martinez JL: Fitness of in vitro selected Pseudomonas aeruginosa nalB and nfxB multidrug resistant mutants. J Antimicrob Chemother 2002, 50: 657-664. 10.1093/jac/dkf185

Linares JF, Lopez JA, Camafeita E, Albar JP, Rojo F, Martinez JL: Overexpression of the multidrug efflux pumps MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN is associated with a reduction of type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol 2005, 187: 1384-1391. 10.1128/JB.187.4.1384-1391.2005

Hocquet D, Berthelot P, Roussel-Delvallez M, Favre R, Jeannot K, Bajolet O, Marty N, Grattard F, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Bingen E, Husson MO, Couetdic G, Plésiat P: Pseudomonas aeruginosa may accumulate drug resistance mechanisms without losing its ability to cause bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007, 51: 3531-3536. 10.1128/AAC.00503-07

Jeannot K, Elsen S, Köhler T, Attree I, van Delden C, Plésiat P: Resistance and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains overproducing the MexCD-OprJ efflux pump. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008, 52: 2455-2462. 10.1128/AAC.01107-07

Garnacho-Montero J, Sa-Borges M, Sole-Violan J, Barcenilla F, Escoresca-Ortega A, Ochoa M, Cayuela A, Rello J: Optimal management therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia: an observational, multicenter study comparing monotherapy with combination antibiotic therapy. Crit Care Med 2007, 35: 1888-1895. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275389.31974.22

Kang CI, Kim SH, Kim HB, Park SW, Choe YJ, Oh MD, Kim EC, Choe KW: Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2003, 37: 745-751. 10.1086/377200

Clec'h C, Timsit JF, De Lassence A, Azoulay E, Alberti C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Mourvilier B, Troche G, Tafflet M, Tuil O, Cohen Y: Efficacy of adequate early antibiotic therapy in ventilator-associated pneumonia: influence of disease severity. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 1327-1333. 10.1007/s00134-004-2292-7

Nguile-Makao M, Zahar JR, Francais A, Tabah A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Allaouchiche B, Goldgran-Toledano D, Azoulay E, Adrie C, Jamali S, Clec'h C, Souweine B, Timsit JF: Attributable mortality of ventilator-associated pneumonia: respective impact of main characteristics at ICU admission and VAP onset using conditional logistic regression and multi-state models. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 781-789. 10.1007/s00134-010-1824-6

Micek ST, Lloyd AE, Ritchie DJ, Reichley RM, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH: Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection: importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49: 1306-1311. 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1306-1311.2005

Blot S, Vandewoude K, De Bacquer D, Colardyn F: Nosocomial bacteremia caused by antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria in critically ill patients: clinical outcome and length of hospitalization. Clin Infect Dis 2002, 34: 1600-1606. 10.1086/340616

Raymond DP, Pelletier SJ, Crabtree TD, Evans HL, Pruett TL, Sawyer RG: Impact of antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacilli infections on outcome in hospitalized patients. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: 1035-1041. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000060015.77443.31

Zahar JR, Clec'h C, Tafflet M, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Jamali S, Mourvillier B, De Lassence A, Descorps-Declere A, Adrie C, Costa de Beauregard MA, Azoulay E, Schwebel C, Timsit JF, Outcomerea Study Group: Is methicillin resistance associated with a worse prognosis in Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia? Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41: 1224-1231. 10.1086/496923

Aloush V, Navon-Venezia S, Seigman-Igra Y, Cabili S, Carmeli Y: Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa : risk factors and clinical impact. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006, 50: 43-48. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.43-48.2006

Carmeli Y, Troillet N, Eliopoulos GM, Samore MH: Emergence of antibiotic resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa : comparison of risks associated with different antipseudomonal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999, 43: 1379-1382.

Harris AD, Perencevich E, Roghmann MC, Morris G, Kaye KS, Johnson JA: Risk factor for piperacillin-tazobactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa among hospitalized patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002, 46: 854-858. 10.1128/AAC.46.3.854-858.2002

Reinhardt A, Kohler T, Wood P, Rohner P, Dumas JL, Ricou B, van Delden C: Development and persistence of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa : a longitudinal observation in mechanically ventilated patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007, 51: 1341-1350. 10.1128/AAC.01278-06

El Amari EB, Chamot E, Auckenthaler R, Pechère JC, van Delden C: Influence of previous exposure to antibiotic therapy on the susceptibility pattern of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremic isolates. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 33: 1859-1864. 10.1086/324346

Sugimura M, Maseda H, Hanaki H, Nakae T: Macrolide antibiotic-mediated downregulation of MexAB-OprM efflux pump expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008, 52: 4141-4144. 10.1128/AAC.00511-08

Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND: Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa : clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009, 22: 582-610. 10.1128/CMR.00040-09

Paramythiotou E, Lucet JC, Timsit JF, Vanjak D, Paugam-Burtz C, Trouillet JL, Belloc S, Kassis N, Karabinis A, Andremont A: Acquisition of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients in intensive care units: role of antibiotics with antipseudomonal activity. Clin Infect Dis 2004, 38: 670-677. 10.1086/381550

Acknowledgements

Collaborators of the OUTCOMEREA study group:

Scientific committee: Jean-François Timsit (Hôpital Albert Michallon and INSERM U823, Grenoble, France), Elie Azoulay (Medical ICU, Hôpital Saint Louis, Paris, France), Yves Cohen (ICU, Hôpital Avicenne, Bobigny, France), Maïté Garrouste-Orgeas (ICU Hôpital Saint- Joseph, Paris, France), Lilia Soufir (ICU, Hôpital Saint-Joseph, Paris, France), Jean-Ralph Zahar (Microbiology Department, Hôpital Necker, Paris, France), Christophe Adrie (ICU, Hôpital Delafontaine, Saint Denis, France), Michael Darmon (Medical ICU, University Hospital St Etienne, France), and Christophe Clec'h (ICU, Hôpital Avicenne, Bobigny, and INSERM U823, Grenoble, France).

Biostatistical and informatics expertise: Jean-Francois Timsit (Hôpital Albert Michallon and Integrated research center U823, Grenoble, France), Corinne Alberti (Medical Computer Sciences and Biostatistics Department, Robert Debré, Paris, France), Adrien Français (INSERM U823, Grenoble, France), Aurélien Vesin INSERM U823, Grenoble, France), Christophe Clec'h (ICU, Hôpital Avicenne, Bobigny, and INSERM U823, Grenoble, France), Frederik Lecorre (Supelec, France), and Didier Nakache (Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, Paris, France), Aurélien Vannieuwenhuyze (Tourcoing, France).

Investigators of the Outcomerea database: Christophe Adrie (ICU, Hôpital Delafontaine, Saint Denis, France), Bernard Allaouchiche (ICU, Edouard Herriot Hospital, Lyon), Caroline Bornstain (ICU, Hôpital de Montfermeil, France), Alexandre Boyer (ICU, Hôpital Pellegrin, Bordeaux, France), Antoine Caubel (ICU, Hôpital Saint-Joseph, Paris, France), Christine Cheval (SICU, Hôpital Saint-Joseph, Paris, France), Marie-Alliette Costa de Beauregard (Nephrology, Hôpital Tenon, Paris, France), Jean-Pierre Colin (ICU, Hôpital de Dourdan, Dourdan, France), Mickael Darmon (ICU, CHU Saint Etienne), Anne-Sylvie Dumenil (Hôpital Antoine Béclère, Clamart France), Adrien Descorps-Declere (Hôpital Antoine Béclère, Clamart France), Jean-Philippe Fosse (ICU, Hôpital Avicenne, Bobigny, France), Samir Jamali (ICU, Hôpital de Dourdan, Dourdan, France), Hatem Khallel (ICU, Cayenne General Hospital), Christian Laplace (ICU, Hôpital Kremlin-Bicêtre, Bicêtre, France), Alexandre Lauttrette (ICU, CHU G Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand), Thierry Lazard (ICU, Hôpital de la Croix Saint-Simon, Paris, France), Eric Le Miere (ICU, Hôpital Louis Mourier, Colombes, France), Laurent Montesino (ICU, Hôpital Bichat, Paris, France), Bruno Mourvillier (ICU, Hôpital Bichat, France), Benoît Misset (ICU, Hôpital Saint-Joseph, Paris, France), Delphine Moreau (ICU, Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France), Etienne Pigné (ICU, Hôpital Louis Mourier, Colombes, France), Bertrand Souweine (ICU, CHU G Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand), Carole Schwebel (CHU A Michallon, Grenoble, France), Gilles Troché (Hôpital Antoine, Béclère, Clamart France), Marie Thuong (ICU, Hôpital Delafontaine, Saint Denis, France), Guillaume Thierry (ICU, Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France), Dany Toledano (CH Gonnesse, France), and Eric Vantalon (SICU, Hôpital Saint-Joseph, Paris, France).

Study monitors: Caroline Tournegros, Loic Ferrand, Nadira Kaddour, Boris Berthe, Samir Bekkhouche, Sylvain Anselme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CK participated in the study design and in the redaction of the draft and the final manuscript. JFT conceived the study design and coordinated the data-capture, the data cleaning, the statistical analysis and the redaction of the final manuscript. YD, JRZ, MGO, EA, ASD, CA and YC participated in the patients enrolment into the study. CF participated in study design, and in the redaction of the final manuscript. AV performed the statistical analysis. BA coordinated the redaction of the final manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaminski, C., Timsit, JF., Dubois, Y. et al. Impact of ureido/carboxypenicillin resistance on the prognosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Care 15, R112 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10136

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10136