Abstract

Introduction

Observational studies suggest statin therapy reduces incident sepsis, but few studies have examined the impact on new organ failure. We tested the hypothesis that statin therapy, administered for standard clinical indications to ventilated intensive care unit patients, prevents acute organ failure without harming the liver.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, single-centre cohort study in a tertiary mixed medical/surgical intensive care unit. Mechanically ventilated patients without nonrespiratory organ failure within 24 hours after admission were assessed (during the first 15 days) for new acute organ failure (defined as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score 3 or 4), liver failure (defined as new hepatic SOFA ≥3, or a 1.5 times increase of bilirubin from baseline to a value ≥20 mmol/l), and alanine transferase (ALT) > 165 IU/l. The effect of statin administration was explored in generalised linear mixed models.

Results

A total of 1,397 patients were included. Two hundred and nineteen patients received a median (interquartile range) of three (two, eight) statin doses. Patients receiving statins were older (67.4 vs. 55.5 years, P < 0.0001), less likely female (25.1% vs. 37.9%, P = 0.0003) and sicker (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score 20.3 vs. 17.8, P < 0.0001). Considering outcome events at least 1 day after statin administration, statin patients were equally likely to develop acute organ failure (28.4% vs. 22.3%, P = 0.29) and hepatic failure (9.5% vs. 7.6%, P = 0.34), but were more likely to experience an ALT increase to > 165 IU/l ((11.2% vs. 4.8%, P = 0.0005). Multivariable analysis showed that APACHE II score (odds ratio (OR) = 1.05 per point; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.03 to 1.07) and APACHE II admission category (P < 0.0001), but not statin administration (OR = 1.21; 95% CI = 0.92 to 1.62), were significantly associated with acute organ failure occurring on or after the day of first statin administration. Statin administration was not associated with liver impairment (OR = 1.08; 95% CI = 0.66 to 1.77) but was associated with a rise in ALT > 165 IU/l (OR = 2.25; 95% CI = 1.32 to 3.84), along with APACHE II score (P = 0.016) and admission ALT (P = 0.0001).

Conclusions

Concurrent statin therapy does not appear to protect against the development of new acute organ failure in critically ill, ventilated patients. The lack of effect may be due to residual confounding, a relatively low number of doses received, or an absence of true effect. Randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm a protective effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many patients suffering from severe infections and early sepsis - conditions associated with deterioration and the development of acute organ failure - require mechanical ventilation after intensive care unit (ICU) admission [1–3]. Mechanical ventilation is associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia and increases the risk of developing other nonrespiratory organ failures [1]. In this context, acute organ failure appears to occur mostly during the first 10 days after admission and is associated with an increased risk of death [1, 3, 4]. Because many mediator-targeting treatments for established severe sepsis have failed in randomised trials, an incentive exists to prevent the onset of acute organ failure [5].

A candidate therapy to prevent acute organ failure is the statin class of drugs, which may dampen the disproportionate innate immune response following microbial invasion [6–10]. While numerous observational studies support the notion of improved sepsis-related outcome in those patients receiving long-term statin therapy, it is not known whether such therapy protects critically ill patients against the development of new acute organ failure or the worsening of existing organ dysfunction [11, 12]. Furthermore, while statins are generally safe and well tolerated in the outpatient population, their safety in the critically ill patient, particularly with respect to liver function, is unknown [13].

Our objectives were to determine whether statin therapy, as administered by clinicians to a cohort of mechanically ventilated patients without nonrespiratory organ failure within 24 hours of ICU admission, (1) reduces the incidence of a composite endpoint of new nonrespiratory organ failure or the worsening of existing respiratory dysfunction during the first 15 days of admission, and (2) is associated with liver impairment as determined by changes in bilirubin and alanine transferase (ALT). We hypothesised that statin therapy does not worsen liver function in this high-risk, clinically important population and protects them against new acute organ failure.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

We performed a retrospective cohort study in which all patients (regardless of diagnosis) receiving mechanical ventilation but without nonrespiratory failure within 24 hours of admission to the ICU were followed until ICU discharge, for a maximum of 15 days [14]. During the follow-up period we assessed organ function (defined by the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score) and ALT levels daily [14].

The study was performed in a single, tertiary academic, medical-surgical ICU and included patients admitted between June 2002 and May 2006. Data were extracted from the Clinical Information System (CareVue™; Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The Clinical Information System is used for all aspects of patient management. All drug prescriptions are electronic, and the system interfaces with the institution's laboratory database and all monitoring equipment and thus stores all physiological, treatment and pharmacological information related to the patient's ICU stay.

Participants

All adult (> 16 years of age) patients requiring mechanical ventilation on admission to the ICU were eligible. We excluded those patients re-admitted to the ICU during their current hospitalisation, patients with any nonrespiratory organ failure within 24 hours of admission (defined by SOFA ≥3), and patients missing admission data that precluded the determination of baseline organ function.

Data collection and follow-up

Raw data were extracted from the Clinical Information System and transferred to a relational database (Microsoft Access™; Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA). The study database was programmed to calculate the SOFA score.

Patients were followed until ICU discharge, for a maximum of 15 days, because previous data from a large international study suggest that deterioration occurs mostly during the first 10 days after admission [1]. During the follow-up period, physiological, biochemical and treatment data were collected daily. The vital status at ICU discharge and hospital discharge and the respective lengths of stay were recorded.

Exposure and outcome definitions

The main exposure variable was statin therapy received in the ICU during the follow-up period. Statin exposure was defined as the documented administration of a prescribed dose at any time during the 15-day follow-up period.

The specific indications for the statin prescription were unknown. The critical care pharmacists, however, routinely contacted the patients' healthcare providers and families to elicit information regarding chronic medications, including prior statin prescriptions. During the study period it was ICU policy, monitored by the critical care pharmacists, to continue statin therapy when previously prescribed and to start a new prescription for recognised indications (for example, an acute coronary syndrome).

There were three outcomes of interest. Acute organ failure was defined by either worsening respiratory function compared with admission (defined as achieving a SOFA respiratory score of 3 or 4 in those with a lower score (0, 1 or 2) on admission, or an increase in SOFA respiratory score to 4 for those with a baseline SOFA of 3) or new nonrespiratory organ failure (defined by a SOFA score of 3 or 4 for any of the cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, or haematological systems). Since all patients were sedated we did not consider the neurological element of SOFA in the analysis. The outcome of liver impairment was defined either by new hepatic failure, (defined as hepatic SOFA ≥3) or by an increase of bilirubin ≥1.5 times from baseline to a value ≥20 mmol/l. We separately considered the outcome of maximum ALT > 165 IU/l (three times the laboratory's upper limit of normal).

We were interested in measuring the effect of statin administration on both the incidence of liver failure (as defined by SOFA) and on more subtle changes in function. We therefore deliberately used conservative cut-off values to increase sensitivity and avoid bias away from the null hypothesis of no harm.

Statistical methods

Data are presented as the mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range) or number (percentage) as appropriate. Baseline differences between exposure groups were compared using Student's t test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for binary variables, as appropriate. We report the proportion of patients with missing values. In unadjusted analyses, we handled missing data in the following manner. Values of bilirubin missing on some days were imputed on a value carried forward or value carried backward basis. Bilirubin (n = 20) and ALT (n = 21) values missing on all patient-days were assumed to be normal, representing the most conservative approach. To calculate the number of days of acute organ failure, liver impairment, and ALT > 165 IU/l, we counted the number of days that each of these events occurred without requiring that they be consecutive.

Statin patients were classified as unexposed during the days preceding the administration of the first statin dose, and as exposed thereafter. For the descriptive analyses, we report for the statin group the number of outcome events that occurred before statin administration, on the same day or after statin administration, and at least 1 day after statin administration.

To investigate the effect of treatment duration we performed post hoc analyses, comparing the outcome events in patients who received at least seven statin doses with nonstatin-exposed patients who were in the ICU for at least 7 days.

We analysed the effect of statin administration on the outcomes of interest using a generalised linear mixed model with logit link function while accounting for repeated measures using an autoregressive correlation structure. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. The effect of statins was adjusted for age, gender, admission APACHE II score, baseline total SOFA score (excluding the neurological component), and main admission category (as defined by APACHE II score) [15]. For the generalised linear mixed models we considered outcome events in the statin group if they occurred on the day of statin or after statin administration.

We interpreted P ≤ 0.05 as statistically significant using two-sided tests. We used SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) for all analyses. We used a convenience sample size based on the data available for the chosen study period to calculate effect estimates and confidence intervals.

Ethics

The present study was approved by the institutional review board of Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, which waived the need for informed consent.

Results

Descriptive data

During the study period, 4,621 patients were admitted to the ICU (see Figure 1). Of these, 3,135 patients were excluded because they were not ventilated, had nonrespiratory organ failure, had already been admitted to the ICU during the same hospitalisation or had missing baseline data. We therefore included 1,397 patients in the final study cohort. The admission category, as defined by APACHE II score, was missing in 45/1,397 (3.2%) patients while 17/1,397 (1.26%) patients were categorised as metabolic. Because only one patient in the metabolic category received a statin, the entire category was excluded from the regression analyses.

Two hundred and nineteen patients received a median of 3 (2, 8) statin doses (Table 1). Of these, 70 patients (32.0%), 77 patients (35.2%), 27 patients (12.3%) and 17 patients (7.8%) were started on days 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. The most common statin administered was simvastatin (72.2%; median dose 20 mg, range 10 to 80 mg), followed by atorvastatin (20.9%) and pravastatin (6.9%).

Patients receiving statins were older (67.4 vs. 55.5 years, P < 0.0001), less likely female (25.1% vs. 37.9%, P = 0.0003) and had higher APACHE II scores (20.3 vs. 17.8, P < 0.0001) than the nonstatin patients. Admission respiratory function was worse in the statin group (P < 0.0001), which had more prevalent respiratory failure (SOFA 3 or 4) and less prevalent respiratory dysfunction (SOFA 1 or 2).

The baseline total nonrespiratory SOFA score was higher in the statin group due to the presence of higher extreme values: median values were 1 (0, 2) for both groups (P = 0.0005), but the mean was 1.49 (1.31) in the statin group and 1.18 (1.28) in the nonstatin group (P = 0.001). At baseline, statin patients were 1.9 and 5.3 times more likely to have renal (P < 0.0001) and cardiovascular (P < 0.0001) failure, respectively, but there was no difference in haematological failure (P = 0.54). There was no difference in baseline hepatic SOFA score (P = 0.49), although the baseline ALT was statistically significantly higher in the statin group (34 vs. 24 IU/l, P < 0.0001).

Unadjusted outcome data

Overall, 380 (27.2%) patients developed acute organ failure. Of these patients, 21 (1.5%) in the statin group developed acute organ failure before a statin was administered. Sixty-seven (33.8%) statin patients developed acute organ failure on or after the day of first statin administration compared with 292 patients (24.8%) in the nonstatin group (P = 0.0073) (Table 2). Furthermore, 52 (28.4%) statin patients developed acute organ failure at least 1 day after the first statin administration compared with 292 (24.8%) nonstatin patients (P = 0.29). There were also no differences in the time to organ failure (3 (3, 4) vs. 3 (2, 5) days in statin vs. nonstatin groups; P = 0.63) or duration of organ failure (2 (1, 5) days in both groups; P = 0.77).

In total, 117 (8.4%) patients developed liver impairment. Of these, five patients (0.4%) in the statin group developed liver impairment before a statin was administered. There were no differences observed in statin patients who developed liver impairment on or after the first stain administration (10.8% vs. 7.7%, P = 0.11), or in statin patients who developed liver impairment at least 1 day after the first statin administration (9.5% vs. 7.6%, P = 0.34). Again, no differences were seen in the time to liver impairment (4 (3, 6) vs. 5 (3, 8) days; P = 0.46) or duration of liver impairment (1 (1, 4) vs. 2 (1, 3) days; P = 0.84).

At baseline, 84 patients had an ALT above the a priori defined value of 165 IU/l that defined an outcome, and were therefore not included in the ALT analysis. In the remainder, the maximum ALT was 33 (18, 69) and 50 (28, 110) IU/l in the nonstatin and statin groups, respectively. The ALT rose above 165 IU/l in 77 (5.9%) patients, and occurred more frequently in statin patients (11.6% considering events on or after the day of first statin administration vs. 4.8%, P = 0.0002). Similarly, a rise in ALT above 165 IU/l was more common in the statin group when outcomes at least 1 day after the first statin administration were considered (11.2% vs. 4.8%, P = 0.0005). The timing of onset (8 (5, 12) vs. 6 (4, 11) days after ICU admission, P = 0.35) and the duration of the ALT rise (3 (1, 4) vs. 2 (1, 4) days, P = 0.66) were similar in statin and nonstatin patients.

The overall lengths of ICU and hospital stays were 5 (3, 10) and 15 (8, 33) days, respectively. Patients receiving statins stayed longer in the ICU (by 3 days, P < 0.0001) and in the hospital (by 7 days, P < 0.0001). Overall mortality in the ICU (12.7%) and hospital (19.3%) was similar in statin and nonstatin patients (P = 0.96 and P = 0.21, respectively).

Regression analyses

In univariable analysis, statin exposure, increasing age, higher admission APACHE II and admission SOFA scores, and APACHE II admission category were associated with acute organ failure (Table 3). After covariate adjustment, the effect of statin administration was nonsignificant (OR = 1.22; 95% CI = 0.92 to 1.62; P = 0.17); only the APACHE II score (OR = 1.05 per point; 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.07; P < 0.0001) and APACHE II admission category (P < 0.0001) were significantly associated with acute organ failure. Relative to the APACHE II respiratory admission category, the cardiovascular category was associated with a higher risk of acute organ failure (OR = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.06 to 1.69; P = 0.015), while the neurological category was associated with a lower risk (OR = 0.48; 95% CI = 0.33 to 0.71; P = 0.0002). Duration of treatment of at least 7 days was not associated with acute organ failure (n = 437; OR = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.53 to 1.23; P = 0.33).

In univariable analysis, statin exposure was not associated with liver impairment (OR = 1.41; 95% CI = 0.89 to 2.24; P = 0.14; Table 4). While higher APACHE II and baseline SOFA scores and the APACHE II admission category were associated with an increased risk of liver impairment, female gender and lesser degrees of hepatic dysfunction (hepatic SOFA score = 1) appeared to be protective. After covariate adjustment, statin exposure was not associated with liver impairment (OR = 1.08; 95% CI = 0.66 to 1.77; P = 0.75). Increasing APACHE II score (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.08; P = 0.0007) and total nonhepatic SOFA score (OR = 1.29; 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.50; P < 0.0009) were strongly associated with liver impairment. Patients with mild hepatic dysfunction (SOFA score = 1) had one-half the odds of developing liver impairment compared with those with no dysfunction (OR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.30 to 0.79; P = 0.0032). Female patients were less likely to develop liver impairment (OR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.42 to 99; P = 0.043). Treatment duration of at least 7 days was not associated with an increased risk of liver impairment (n = 437; OR = 0.54; 95% CI = 0.24 to 1.20; P = 0.13).

In both univariable and multivariable analysis, statin exposure (adjusted OR = 2.25; 95% CI = 1.32 to 3.84; P = 0.003), APACHE II score (OR = 1.04; 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.08; P = 0.016) and admission ALT (OR = 1.11; 95% CI = 1.05 to 1.18; P = 0.0001) were strongly associated with a rise in ALT above 165 IU/l. Statin exposure remained associated with an ALT increase in those who received at least seven doses (n = 407; OR = 2.39, 95% CI = 1.25 to 4.59; P = 0.009).

Discussion

The major finding from our single-centre retrospective cohort study of mechanically ventilated patients without baseline extrapulmonary organ failure is that concurrent statin therapy did not reduce the incidence of new acute organ failure. Furthermore, while statin therapy was associated with a statistically significant but clinically small rise in the ALT level, it was not associated with liver impairment as defined by changes in bilirubin. Statin-exposed patients were on average older, predominantly male and were sicker (as reflected by higher APACHE II and total SOFA scores) on admission. The overall incidence of acute organ failure in this cohort was 25.3%, took a median 3 days to develop and lasted for a median of 2 days, with no differences between statin and nonstatin groups.

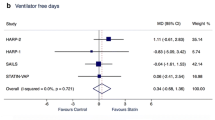

The present study is the first designed specifically to investigate the effect of concurrent statin therapy on the incidence of acute organ failure in ventilated, critically ill patients. In contrast, the existing observational literature suggests that statin therapy protects against sepsis-related morbidity and mortality [11, 12]. These studies have focused on pre-ICU admission chronic statin use, different populations and outcomes, and have used widely varying selection criteria. Studies exploring statin effects in the ICU have predominantly included patients with established severe sepsis.

Several smaller observational studies have investigated statin administration in the ICU and found variable effects on clinical outcomes. Fernandez and colleagues examined 438 patients at high risk of ICU-acquired infection, defined as those receiving mechanical ventilation for 96 hours [16]. Those who continued previous statin therapy while in the ICU developed statistically nonsignificantly fewer infections than statin nonusers, but were more likely to die in hospital. Schmidt and colleagues found lower mortality in 40 ICU patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome receiving statin therapy compared with 80 age- and sex-matched multiple organ dysfunction syndrome patients not receiving statins [17]. Dobesh and colleagues enrolled 188 patients with established severe sepsis (statin exposed, n = 60) and found a significantly reduced risk of hospital mortality [18]. In contrast, de Saint Martin and colleagues found no differences between statin-exposed and nonexposed patients (n = 921) older than 40 years of age admitted with fever in multiple outcomes (mortality, length of hospitalisation, ICU admission, and admission to convalescent homes) [19]. Finally, Kor and colleagues measured the development and progression of pulmonary and nonpulmonary organ failure for 178 patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome and found no statin effects on the PaO2/FiO2 ratio and total SOFA score in univariable analyses [20]. Inferences from all these studies are subject to confounding by indication.

The present study has several strengths. First, it is the largest study specifically designed to investigate the effect of concurrent statin therapy on the incidence of acute organ failure in mechanically ventilated patients without extrapulmonary organ failure, and is the only study reporting effects on bilirubin and ALT values. Second, the study population is well-defined and clinically important, because the incidence of new acute organ failure is high and potentially preventable. Third, exposure was based on statin administration rather than prescription. Lastly, the statistical models appropriately account for repeated measures of daily assessment organ function per patient.

Our study shares several limitations of the existing observational literature. First, although we conducted careful multivariable analyses, we cannot eliminate the possibility of residual confounding. In particular, we did not know the clinical indications for statin treatment, but used the APACHE II admission category, which includes a cardiovascular category, as an adjustment variable. In contrast, information bias seems less likely since only 2.9% of eligible patients were excluded and 4.4% were excluded from regression models due to missing data. Second, we did not have data on preadmission statin treatment, leaving the possibility that a significant proportion of those patients deemed unexposed may have been prior users. During the study period our unit policy was to continue previous statin therapy, and dedicated ICU pharmacists routinely interviewed patients, relatives and the patients' general practitioners to obtain information on all chronic medications. If acute withdrawal of statin therapy is harmful, the effect of this misclassification bias would tend to diminish any findings of benefit [21]. Importantly, recently published data from a randomised controlled trial in which critically ill patients were randomised to continue or stop prior atorvastatin treatment showed no outcome differences between the exposure groups [22]. Third, we cannot confirm whether statins were actually absorbed after enteral administration. Recent data do show, however, that enteral atorvastatin is well absorbed [23]. Fourth, we were unable to study the association between statin therapy and muscle complications because creatinine kinase is not routinely collected for clinical purposes and the data were therefore not available for analyses. Fifth, we may have underestimated the association between statin administration and outcomes due to the effect of immortal time bias [24]. Finally, the study was performed using data obtained from a single academic institution and may not be generalisable to other study populations.

The reasons for the apparent failure to demonstrate a benefit are unclear, but include the potential sources of error inherent in all observational methodologies, the relatively low number of doses received (median of three), or the absence of any beneficial biological effect. Although the subgroup analyses also do not suggest a beneficial effect, the results must be interpreted carefully given that the analyses were post hoc and the study was not designed with these analyses in mind. Craig and colleagues, however, recently showed that treatment with simvastatin appears to be safe and may be associated with an improvement in organ dysfunction in acute lung injury [25]. Lastly, although we previously established biological plausibility and proposed biological pathways modulated by statin therapy, it is possible that these pathways are not the ones involved in the development of acute organ failure [7, 9].

Conclusions

Based on these results, concurrent statin therapy does not appear to protect against the development of new acute organ failure in critically ill, ventilated patients, but it does not appear to cause liver failure. While therapy was associated with a rise in ALT, the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear. Given the limited inferences from observational data and persistent biological rationale for the benefit of statin administration in this population at high risk of organ failure, sufficiently powered randomised controlled trials are needed.

Key messages

-

Many patients with early sepsis develop acute organ failure, and no mediator-targeting treatments able to prevent this progression are available.

-

Current observational data suggest that statins may prevent sepsis-related morbidity and mortality.

-

In the largest study specifically designed to test whether statins prevent the onset of new acute organ failure in ventilated ICU patients, we found no evidence of protection.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

alanine transferase

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IU:

-

international units

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PaO2/FiO2:

-

partial pressure of arterial oxygen/inspired fraction of oxygen

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

References

Alberti C, Brun-Buisson C, Chevret S, Antonelli M, Goodman SV, Martin C, Moreno R, Ochagavia AR, Palazzo M, Werdan K, Le Gall JR: Systemic inflammatory response and progression to severe sepsis in critically ill infected patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171: 461-468. 10.1164/rccm.200403-324OC

Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP: The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA 1995, 273: 117-123. 10.1001/jama.273.2.117

Brun-Buisson C: The epidemiology of the systemic inflammatory response. Intensive Care Med 2000,26(Suppl 1):S64-S74. 10.1007/s001340051121

Alberti C, Brun-Buisson C, Goodman SV, Guidici D, Granton J, Moreno R, Smithies M, Thomas O, Artigas A, Le Gall JR: Influence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis on outcome of critically ill infected patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 168: 77-84. 10.1164/rccm.200208-785OC

Natanson C, Esposito CJ, Banks SM: The sirens' songs of confirmatory sepsis trials: selection bias and sampling error. Crit Care Med 1998, 26: 1927-1931. 10.1097/00003246-199812000-00001

Shyamsundar M, McKeown ST, O'Kane CM, Craig TR, Brown V, Thickett DR, Matthay MA, Taggart CC, Backman JT, Elborn JS, McAuley DF: Simvastatin decreases lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation in healthy volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 179: 1107-1114. 10.1164/rccm.200810-1584OC

Novack V, Eisinger M, Frenkel A, Terblanche M, Adhikari NK, Douvdevani A, Amichay D, Almog Y: The effects of statin therapy on inflammatory cytokines in patients with bacterial infections: a randomized double-blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1255-1260. 10.1007/s00134-009-1429-0

Terblanche M, Almog Y, Rosenson RS, Smith TS, Hackam DG: Statins: panacea for sepsis? Lancet Infect Dis 2006, 6: 242-248. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70439-X

Terblanche M, Almog Y, Rosenson RS, Smith TS, Hackam DG: Statins and sepsis: multiple modifications at multiple levels. Lancet Infect Dis 2007, 7: 358-368. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70111-1

Terblanche M, Smith TS, Adhikari NK: Statins, bugs and prophylaxis: intriguing possibilities. Crit Care 2006, 10: 168. 10.1186/cc5056

Falagas ME, Makris GC, Matthaiou DK, Rafailidis PI: Statins for infection and sepsis: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008, 61: 774-785. 10.1093/jac/dkn019

Tleyjeh IM, Kashour T, Hakim FA, Zimmerman VA, Erwin PJ, Sutton AJ, Ibrahim T: Statins for the prevention and treatment of infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2009, 169: 1658-1667. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.286

Law M, Rudnicka AR: Statin safety: a systematic review. Am J Cardiol 2006, 97: 52C-60C. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.010

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG: The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996, 22: 707-710. 10.1007/BF01709751

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE: APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985, 13: 818-829. 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009

Fernandez R, De Pedro VJ, Artigas A: Statin therapy prior to ICU admission: protection against infection or a severity marker? Intensive Care Med 2005, 32: 160-164. 10.1007/s00134-005-2743-9

Schmidt H, Hennen R, Keller A, Russ M, Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K, Buerke M: Association of statin therapy and increased survival in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2006, 32: 1248-1251. 10.1007/s00134-006-0246-y

Dobesh PP, Klepser DG, McGuire TR, Morgan CW, Olsen KM: Reduction in mortality associated with statin therapy in patients with severe sepsis. Pharmacotherapy 2009, 29: 621-630. 10.1592/phco.29.6.621

de Saint Martin L, Tande D, Goetghebeur D, Pan-Lamande M, Segalen Y, Pasquier E: Statin use does not affect the outcome of acute infection: a prospective cohort study. Presse Med 2010, 39: e52-e57. 10.1016/j.lpm.2009.09.022

Kor DJ, Iscimen R, Yilmaz M, Brown MJ, Brown DR, Gajic O: Statin administration did not influence the progression of lung injury or associated organ failures in a cohort of patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1039-1046. 10.1007/s00134-009-1421-8

Heeschen C, Hamm CW, Laufs U, Snapinn S, Bohm M, White HD: Withdrawal of statins increases event rates in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2002, 105: 1446-1452. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000012530.68333.C8

Kruger PS, Harward ML, Jones MA, Joyce CJ, Kostner KM, Roberts MS, Venkatesh B: Continuation of statin therapy in patients with presumed infection: a randomised controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 774-781. 10.1164/rccm.201006-0955OC

Kruger PS, Freir NM, Venkatesh B, Robertson TA, Roberts MS, Jones M: A preliminary study of atorvastatin plasma concentrations in critically ill patients with sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 717-721. 10.1007/s00134-008-1358-3

Shintani AK, Girard TD, Eden SK, Arbogast PG, Moons KG, Ely EW: Immortal time bias in critical care research: application of time-varying Cox regression for observational cohort studies. Crit Care Med 2009, 37: 2939-2945. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b7fbbb

Craig TR, Duffy MJ, Shyamsundar M, McDowell C, C OK, Elborn JS, McAuley DF: A randomized clinical trial of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibition for acute lung injury (the HARP study). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 620-626. 10.1164/rccm.201003-0423OC

Acknowledgements

The study was financially supported by the Department of Critical Care, Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK) and the Department of Critical Care Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). MJT, SB and RB wish to acknowledge the support of the UK NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MJT conceived the study and developed the protocol, participated in the data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. RP analysed the data and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. CW contributed to the study design, collected data and reviewed the manuscript. NKJA contributed to study design, data analysis, drafting of the manuscript, and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. SB and RB contributed to the study design, interpretation of results and appraised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Terblanche, M.J., Pinto, R., Whiteley, C. et al. Statins do not prevent acute organ failure in ventilated ICU patients: single-centre retrospective cohort study. Crit Care 15, R74 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10063

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10063