Abstract

Background

Recent evidence suggests a role for progesterone in breast cancer development and tumorigenesis. Progesterone exerts its effect on target cells by interacting with its receptor; thus, genetic variations, which might cause alterations in the biological function in the progesterone receptor (PGR), can potentially contribute to an individual's susceptibility to breast cancer. It has been reported that the PROGINS allele, which is in complete linkage disequilibrium with a missense substitution in exon 4 (G/T, valine→leucine, at codon 660), is associated with a decreased risk for breast cancer.

Methods

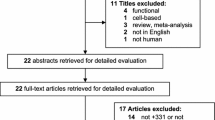

Using a nested case-control study design within the Nurses' Health Study cohort, we genotyped 1252 cases and 1660 matched controls with the use of the Taqman assay.

Results

We did not observe any association of breast cancer risk with carrying the G/T (Val660→Leu) polymorphism (odds ratio 1.10, 95% confidence interval 0.93–1.30). In addition, we did not observe an interaction between this allele and menopausal status and family history of breast cancer as reported previously.

Conclusion

Overall, our study does not support an association between the Val660→Leu PROGINS polymorphism and breast cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Until recently, the role of progesterone on mammary gland tumorigenesis was not well understood. Data from epidemiological studies revealed a higher risk for breast cancer in postmenopausal women who used a combination of estrogens and progestins, in comparison with those women who used estrogens alone [1, 2]. As demonstrated in the progesterone receptor knockout mouse, the physiological effects of progesterone are completely dependent on the presence of its receptor gene, PGR, which exists as a single-copy gene. The PGR gene uses separate promoters and translational start sites to produce two protein isoforms, hPR-A and hPR-B [3–5], that are identical except for an additional 165 amino acids present only in the amino terminus of hPR-B [6, 7]. Although hPR-B shares many important structural domains with hPR-A, the two isoforms are functionally distinct transcription factors [8] that mediate their own response genes and physiological effects with little overlap [9, 10]. The progesterone receptor knockout mouse, in which the functional activity of both hPR-A and hPR-B were simultaneously ablated, revealed that progesterone is required for the formation of ductal and alveolar structures during pregnancy [11, 12]. Selective ablation of PR-B in a mouse model, resulting in the exclusive production of PR-A, revealed that PR-B is necessary for breast formation [13]. Given the evidence described above for the role of progesterone in breast cancer causation, we proposed that variations in the PGR gene might predispose women to breast cancer. Several studies have investigated the Val660 →Leu G/T polymorphism and the PROGINS Alu insertion, which are in complete linkage disequilibrium [14], in association with breast cancer [15–17]. In this study we focused on the Val660→Leu G/T polymorphism that has been reported to be associated with a decreased risk of breast cancer [17].

Materials and methods

Detailed information about this nested case-control study and exposure data has been reported previously [18]. The protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Subjects, Brigham and Women's Hospital. Genotyping assays were performed by the 5' nuclease assay (TaqMan®) by the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). TaqMan primers, probes, and conditions for genotyping assays are available from the authors on request. Genotyping was performed by laboratory personnel blinded to case-control status, and blinded quality control samples were inserted to validate genotyping procedures. Concordance for the blinded samples was 100%.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by using conditional and unconditional logistic regression. In addition to the matching variables, we adjusted for breast cancer risk factors: body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) at age 18 years, weight gain since age 18 years, age at menarche, parity/age at first birth, duration of postmenopausal hormone use, first-degree family history of breast cancer, and history of benign breast disease. We also adjusted for age at menopause in analyses limited to postmenopausal women. Indicator variables for all genotypes were created by using the wild-type genotype as the reference category in the regression models. Because of the low prevalence of homozygous variants, we combined heterozygotes and homozygotes in the logistic regression analysis. Interactions between genotypes and breast cancer risk factors were evaluated by including appropriate interaction terms in unconditional logistic regression models. The nominal likelihood ratio test was used to assess the statistical significance of these interactions. We used SAS version 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all analyses. We tested Hardy–Weinberg agreement by using a χ2 test.

Results and discussion

Our study included a total of 1323 incident breast cancer cases, diagnosed after blood draw to 1 June 2000, and 1854 matched controls. Of these, 1134 cases and 1640 controls were postmenopausal at blood draw, and 112 cases and 121 controls were premenopausal; menopausal status was uncertain in 77 cases and 93 controls. The mean age of cases at blood draw was 57.3 years; for controls it was 57.9 years. Cases and controls had similar mean BMI at blood draw (25.5 versus 25.5 kg/m2) and weight gain since age 18 years (11.6 versus 11.3 kg). In comparison with controls, cases had similar ages at menarche (12.5 versus 12.6 years), first birth (23.0 versus 23.0 years) and age at menopause (48.2 versus 47.9 years). The proportion of women with a first-degree family history of breast cancer was significantly higher among the cases (20.0% versus 15.0%). Cases were also more likely to have a history of benign breast disease (64.0% versus 51.0%) and a longer duration of postmenopausal hormone use (50.3% versus 49.7% current users for five or more years). The study population was predominantly Caucasian (89% of cases, 86% of controls).

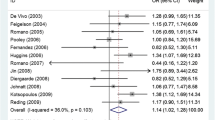

The prevalence of the variant carriers was similar to that in a previous report for Caucasian women [14]: 31% for the cases and 29% for the controls. The genotype distribution of the Val660→Leu polymorphism among the cases and controls was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. We did not observe a statistically significant association of breast cancer among carriers of the Val660→Leu G/T polymorphism. Too few homozygote variants were available in which to analyze the heterozygotes and homozygotes separately. Compared with the G/G wild-type genotype, the adjusted OR for women with G/T and T/T was 1.10 (95% CI 0.93–1.30) (Table 1). Because the previously reported inverse association was confined to premenopausal women, we stratified by menopausal status and observed no association among premenopausal women (adjusted OR 1.21 [95% CI 0.64–2.28]) although we had a relatively small number of women for this analysis (Table 1). The Val660→Leu polymorphism has been suggested to modify the association between family history of breast cancer and breast cancer [17]. We observed no statistically significant interactions between the Val660→Leu polymorphism and first-degree family history of breast cancer. In addition, we selected BMI, history of benign breast disease, and hormone replacement therapy use among postmenopausal women as potential effect modifiers based on biological plausibility. We observed no significant interactions between the Val660→Leu polymorphism and any of these risk factors.

Conclusions

Our data do not support an inverse association between the Val660→Leu polymorphism and breast cancer risk as reported previously [17]. These results are consistent with recent studies of mostly Caucasian women in which no association was observed between this polymorphism and breast cancer risk in either premenopausal or postmenopausal women [15, 16, 19, 20]. Most notable was the study by Spurdle and colleagues, in which a substantial number of premenopausal cases (n = 769) were evaluated [19]. We had limited power to study this association in premenopausal women, but this is the largest study of postmenopausal women reported so far. The large sample size, prospective design and extensive relevant life-style information are among the strengths of this study. In conclusion, our results suggest that there is no association between the Val660→Leu polymorphism and breast cancer risk despite the substantial power of the study (more than 80% power to detect an OR of 0.75 or less for the carrier genotype).

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- LD:

-

linkage disequilibrium

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PGR:

-

progesterone receptor

References

Colditz CA, Rosner B: Cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 70 years according to risk factor status: data from the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000, 152: 950-964. 10.1093/aje/152.10.950.

Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Wan PC, Pike MC: Effect of hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk: estrogen versus estrogen plus progestin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000, 92: 328-332. 10.1093/jnci/92.4.328.

Kastner P, Krust A, Turcotte B, Stropp U, Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Chambon P: Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptor forms A and B. EMBO J. 1990, 9: 1603-1614.

Conneely OM, Maxwell BL, Toft DO, Schrader WT, O'Malley BW: The A and B forms of the chicken progesterone receptor arise by alternate initiation of translation of a unique mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987, 149: 493-501.

Conneely OM, Kettelberger DM, Tsai M-J, Schrader WT, O'Malley BW: The chicken progesterone receptor A and B isoforms are products of an alternate translation initiation event. J Biol Chem. 1989, 264: 14062-14064.

Wen DX, You-Feng X, Mais DE, Goldman ME, McDonnell DP: The A and B isoforms of the human progesterone receptor operate through distinct signaling pathways within target cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994, 14: 8356-8364.

Sartorius CA, Melville MY, Hovland AR, Tung L, Takimoto GS, Horwitz KB: A third transactivation function (AF3) of human progesterone receptors located in the unique N-terminal segment of the B-isoform. Mol Endocrinol. 1994, 8: 1347-1360. 10.1210/me.8.10.1347.

Giangrande PH, Kimbrel EA, Edwards DP, McDonnell DP: The opposing transcriptional activities of the two isoforms of the human progesterone receptor are due to differential cofactor binding. Mol Cell Biol. 2000, 20: 3102-3115. 10.1128/MCB.20.9.3102-3115.2000.

Horwitz KB: The molecular biology of RU486. Is there a role for antiprogestins in the treatment of breast cancer?. Endocr Rev. 1992, 13: 146-163. 10.1210/er.13.2.146.

Richer JK, Jacobsen BM, Manning NG, Abel MG, Wolf DM, Horwitz KB: Differential gene regulation by the two progesterone receptor isoforms in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277: 5209-5218. 10.1074/jbc.M110090200.

Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW: Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1995, 9: 2266-2278.

Lydon JP, Ge G, Kittrell FS, Medina D, O'Malley BW: Murine mammary gland carcinogenesis is critically dependent on progesterone receptor function. Cancer Res. 1999, 59: 4276-4284.

Mulac-Jericevic B, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Conneely OM: Defective mammary gland morphogenesis in mice lacking the progesterone receptor B isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100: 9744-9749. 10.1073/pnas.1732707100.

De Vivo I, Huggins GS, Hankinson SE, Lescault PJ, Boezen M, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ: A functional polymorphism in the promoter of the progesterone receptor gene associated with endometrial cancer risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99: 12263-12268. 10.1073/pnas.192172299.

Manolitsas TP, Englefield P, Eccles DM, Campbell IG: No association of a 306-bp insertion polymorphism in the progesterone receptor gene with ovarian and breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997, 75: 1398-1399.

Lancaster JM, Berchuck A, Carney ME, Wiseman R, Taylor JA: Progesterone receptor gene polymorphism and risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998, 78: 277-

Wang-Gohrke S, Chang-Claude J, Becher H, Kieback DG, Runnebaum IB: Progesterone receptor gene polymorphism is associated with decreased risk for breast cancer by age 50. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 2348-2350.

De Vivo I, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ: A functional polymorphism in the progesterone receptor gene is associated with an increase in breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2003, 63: 5236-5238.

Spurdle AB, Hopper JL, Chen X, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Venter DJ, Southey MC, Chenevix-Trench G: The progesterone receptor exon 4 val660leu G/T polymorphism and risk of breast cancer in Australian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11: 439-443.

Fabjani G, Tong D, Czerwenka K, Schuster E, Speiser P, Leodolter S, Zeillinger R: Human progesterone receptor gene polymorphism PROGINS and risk for breast cancer in Austrian women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002, 72: 131-137. 10.1023/A:1014813931765.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the Nurses' Health Study for their exceptional dedication and commitment to the study, Dr Hardeep Ranu for genotyping and Pati Soule for laboratory support. This research was supported by NIH grants CA82838 (ID) and CA49449 (SEH), and American Cancer Society grant RSG-00-061-04-CCE (ID).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Vivo, I., Hankinson, S.E., Colditz, G.A. et al. The progesterone receptor Val660→Leu polymorphism and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res 6, R636 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr928

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr928